John Williams Always Settles the Score

In 1999, a music videopremiered on MTV’sTotal Request Live.

A gigantic orchestra plays turbulent, churning notes. A propulsive five-note motif suggests an oncoming storm. An 88-piece adult chorus chants mysterious syllables. Trumpets blare, strings surge, and cymbals crash.

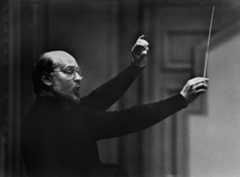

The video blends glossy CGI visuals with footage of the London Symphony Orchestra in performance, their sheet music strewn with eighth notes.

It was the video forJohn Williams’s “Duel of the Fates,” the soundtrack to a pivotal lightsaber duel inStar Wars: Episode I—The Phantom Menace, and the only symphonic track to appear onTotal Request Live ever.

Star Wars music on MTV? It had a lot to do with the immense hype surrounding the new movie at the time. It was also because John Williams’s music itself is undeniably badass—just one astonishing moment in a singular career that is coming to a close.

Last year, it was widely reported that Williams planned to retire from scoring films after his work onThe Fabelmans andIndiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny. In January, Williamswalked back those plans, admitting he couldn’t say no to his frequent collaboratorSteven Spielberg—though as of now, the composer has no confirmed upcoming projects.

But with the return of Indy—along with one of Williams’s most dependable and iconic themes—it seems a fitting time to reflect on the legacy of the composer, who turned 91 this year.

Williams’s resume is like the first appearance of the Imperial Star Destroyer inStar Wars: it just goes on and on and on. Besides the above-mentioned franchises, you likely know his work on theHarry Potter movies,Jaws, Superman,Home Alone,Hook,Jurassic Park,E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, andSchindler’s List, while the diehards treasure the deep cuts:The Witches of Eastwick, Presumed Innocent, JFK, Dracula, The Accidental Tourist.

And aside from his list of credits, Williams is a big reason why we care about movie music today at all.

Movies of Hollywood’s Golden Age were draped in the lush, romantic sound of a full orchestra. By the 1960s and early 1970s, however, that sound had fallen out of favor, making way for the pop-orchestral style of Henry Mancini and then a more jukebox-oriented approach centered on the youth music of the era: Steppenwolf, Simon & Garfunkel, Harry Nilsson.

At the same time, the once dominant cultural force of classical music had lost touch with its audience. It had become less accessible, more complex and esoteric. Concert hall audiences were older, stuffier, and instructed to stifle their applause between movements. You couldn’t hum Schoenberg or Stravinsky. Younger generations, craving melody and feeling, gravitated to jazz, rock, and R&B.

Then withJaws, followed byStar Wars, Williams revived the sound of a bygone Hollywood. Even more fundamentally, he reintroduced a mass audience (including young people) to an invention that had been wowing human beings since the 16th and 17th centuries in Europe: the sprawling and fantastic congregation of instruments and instrumentalists known as the orchestra, a battalion capable of summoning sounds that are deep, transporting, and emotionally expressive. Williams made the orchestraexciting again.

This was the sound that the biggest movies of the following years demanded—a sound with an uncanny power to galvanize emotions and bring fantastical worlds to life. Sometimes, the music itself was a character or plot point: Consider the menacing bass notes inJaws representing the shark, or the five-note phrase inClose Encounters of the Third Kind.

His work ushered in the glorious return of symphonic storytelling: music with detail and color and narrative development that could stand on its own—on a soundtrack album, say—apart from the films themselves. (The reverse does not apply: The movies didn’t really work without the score.) It was an enthralling art form in itself.

And crucially, Williams’s music was catchy. From his earliest scores, the composer possessed a profound ability to create melodies that touched and hooked audiences—tunes that couldeven make a lasting impression on a two-year-old. How many people, outside of contemporary classical music connoisseurs, could recognize a melody from an orchestral piece composed in the last half-century? Yet several John Williams themes have become unforgettable touchstones, transcending the films themselves to become integral to popular culture.

That tunefulness surely contributes to the way Williams’s music has captivated young audiences. His scores forHome Alone, threeHarry Potter movies,E.T.,Star Wars, andJurassic Park—essential films in many upbringings—have introduced countless receptive young minds to the splendors of the orchestra. It’s music that often serves as a magical portal to an appreciation of classical and symphonic music; it’s not a hyperdrive leap fromStar Wars to Holst or Prokofiev, Dvořák or Shostakovich.

For plenty of fans, though, a thorough appreciation of film music—or indeed, an appreciation of John Williams music—is an endpoint unto itself, constituting the bulk of a satisfying orchestral diet. Think of it as the classical music of our time, teaching its devotees to truly, deeply listen. But also, as the MTV placement suggests, it’s classical music that has struck a mighty chord with a sizable audience.

Williams defined the sound of a whole era of moviegoing. He paved the way for other symphonically minded film composers, with Jerry Goldsmith,Howard Shore, and James Horner making estimable contributions to the form. Taking over the Boston Pops Orchestra in 1980, Williams single-handedly brought film music into the concert hall, legitimizing an art form previously dismissed by classical music critics as cultural junk food.

But the truth is in the decades since quality symphonic music has lost its primacy at the movies.

In a time when computers are used for both film editing and composing scores, so much contemporary movie music lacks the nuance, narrative progression, and depth of feeling that characterize Williams’s work.Hans Zimmer, whose sound has dominated blockbusters since the 1990s, coats movies in ambient sonic texture—more sound design than symphony. Harmonic and contrapuntal complexity have taken a backseat to visceral impact.

Movie music of this kind can cause the air in your lungs and the tissues in your chest to vibrate. But can it stir the soul like, say, the theme toJurassic Park? (And that’s not even considering the integrity of the composition process itself; Williams personally writes every note on his staff paper, while Zimmerfarms his scores out to be completed by a stable of composers.)

Williams’s possible retirement comes at a time when the future of movies themselves seems uncertain. A giant sauropod feeding on tree leaves, a fleet of BMX bikes soaring through the air: those scenes—exquisitely and sensitively scored by Williams—felt like shared cultural moments. With the rise of streaming, the state of cinema, and today’s atomized culture more broadly, it’s hard to imagine movies ever inspiring awe in a wide audience in quite the same way.

It’s even harder to imagine them without the music of John Williams.

There’s sure to be a sense of elegy in Williams’s score for the finalIndiana Jones installment. Beyond saying goodbye to a certain fedora-wearing archaeologist, it will feel like the end of a crucial epoch in film music. Yet Williams’s body of work isn’t going anywhere. It will continue to enthrall and inspire whole lifetimes’ worth of listening, study, discussion, and obsession.

“[O]rchestras and films are brother and sister, it seems to me,” Williamsonce said. “And when we can offer a score that an orchestra can play, and there’s room on the canvas for it, as there is inStar Wars, it’s a bonus, and it’s a privilege, and it’s a treat.”

It was a treat indeed.

More Great Stories FromVanity Fair

WhatBari Weiss Means for60 Minutes

All AboutMelania

Meet the British ’90s It Girl Who Wants toMake England Great Again

Anjelica Huston’s Cultured Coolness

Gore Vidal’s Final Feud

The 6 Grisly Films Inspired by Serial KillerEd Gein

Charlie Kirk, Redeemed by the Media

The25 Best Movies to Watch on Netflix This October

From the Archive: The Hollywood SecretKatharine Hepburn Helped Bury