Dark Matter Gets Darker: New Measurements Confound Scientists

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.Here’s how it works.

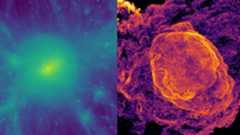

New measurements of tiny galaxies contradict scientists' best model of dark matter, further complicating the already mysterious picture of the stuff that is thought to make up 98 percent of all matter in the universe.

Dark matter, the invisible material thought to permeate the universe, can only be indirectly detected through its gravitational pull on the normal matter that makes up stars and planets.

Best picks for you

This "cold dark matter" model has done remarkably well describing how dark matter behaves in most situations. However, it breaks down when applied to mini "dwarf galaxies," where dark matter appears more spread out than it should be, according to the theory.

According to the model, the centers of galaxies should be packed with dense clumps of the invisible matter. But dark matter appears to be spread evenly throughout Fornax and Sculptor, as well as other dwarf galaxies whose mass distributions have been measured in other ways.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"If a dwarf galaxy were a peach, the standard cosmological model says we should find a dark matter 'pit' at the center," researcher Jorge Peñarrubia of England's University of Cambridge said in a statement. "Instead, the first two dwarf galaxies we studied are like pitless peaches."

The measurements suggest that some part of the theoretical model may have to be revised.

"Our measurements contradict a basic prediction about the structure of colddark matter in dwarf galaxies," said study leader Matt Walker of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass. "Unless or until theorists can modify that prediction, cold dark matter is inconsistent with our observational data."

Don't miss these

Dwarf galaxies like Fornax and Sculptor are especially good places to study dark matter, because they are thought to be almost entirely made up of the stuff. Only one percent of matter in a dwarf galaxy is thought to be the normal matter that makes up stars.

To determine where and how much dark matter inhabits the dwarf galaxies, the researchers studied the motions of 1,500 to 2,500 visible stars, which reflect the gravitational forces acting on them from dark matter.

Some researchers have suggested that when dark matter interacts with normal matter it may tend to spread out, thus decreasing the density of dark matter in thecenters of galaxies. However, so far, the cold dark matter model doesn't predict this.

Either normal matter affects dark matter more than scientists thought, or it isn't cold and slow-moving, the researchers said.

"After completing this study, we know less about dark matter than we did before," Walker said.

The findings will be published in an upcoming issue of The Astrophysical Journal.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter@Spacedotcomand onFacebook.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.