1790

An American Puzzle: Fitting Race in a Box

Census categories for race and ethnicity have shaped how the nation sees itself. Here’s how they have changed over the last 230 years.

Since 1790, the decennial census has played a crucial role in creating and reshaping the ever-changing views of racial and ethnic identity in the United States.

Over the centuries, the census has evolved from one that specified broad categories — primarily “free white” people and “slaves” — to one that attempts to encapsulate the country’s increasingly complex demographics. Thelatest adaptation proposed by the Biden administration in January seeks to allow even more race and ethnicity options for people to describe themselves than the 2020 census did.

If approved, theproposed overhaul would most likely be adopted across all surveys in the country about health, education and the economy. Here’s what the next census could look like.

The country has grown more multiracial, and federal officials now want to capture that complexity. One of the biggest changes would be to combinerace and ethnicityinto a single question.

“Hispanic or Latino” would be one of seven race and/or ethnicity options, rather than in aseparate origin question, as it is now.

The change would also add a check box for“Middle Eastern or North African,” and remove people of this heritage from the“white” definition.

In some ways, the government is attempting to catch up with modern views of racial and ethnic identities.

There are complicated politics at work too, and the proposed changes have provoked criticism among some scholars and activists.

Many Hispanic or Latino U.S. residents mark “some other race,” typically because they don’t see themselves as “Black” or “white.” Supporters of the proposal say the changes reflect that Latinos have long been treated as a distinct racial group in the United States. But Afro-Latino scholars argue that the new method would mask important racial differences among Latinos.

Community leaders have been advocating for a “Middle Eastern or North African” category for years, pointing to the need for better data for this growing population, especially around health care, education and political representation. If the proposal is approved, this would be the first time since the 1970s that a completely new racial or ethnic category is added to the census.

A precise, universally accepted distinction between race and ethnicity does not exist. Instead, there’s a murky history of law, politics and culture around racial identity in America.

“There is no such thing as a perfect question,” said Roberto Ramirez, a population statistics expert at the U.S. Census Bureau. The bureau has conducted numerous tests in recent decades to improve the census so that people can more accurately identify themselves, he said.

If approved, the new race and ethnicity formulation will have wide-ranging impacts. Any organization receiving federal funding — down to local schools — would have to adhere to it. Race data informs how resources are distributed; whether equal employment policies and anti-discrimination laws can be enforced; and how congressional districts are drawn.

Ever since the census began measuring the U.S. population, race has been central to the counting. The census is more than a bureaucratic exercise; it embodies the country’s continued efforts to neatly categorize inherently nuanced and layered identities. Terms that are now widely viewed as outdated or even offensive had their place on the official forms for decades.

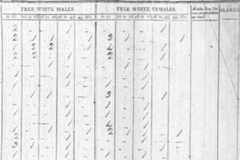

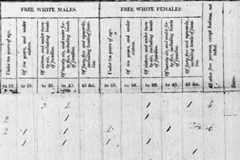

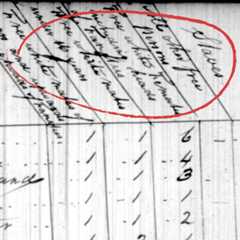

Here’s a copy of the first census in1790.

It separated free “white” people from other free people and enslaved people.

In1850, the term “color” was used for “race,” and “mulatto” was introduced to track people with any trace of African blood.

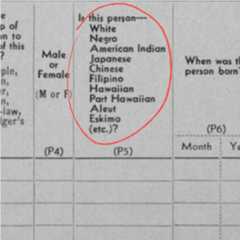

In1870, the census added a “Chinese” category as anxieties over immigration from China rose.

In1890, the census identified African Americans by thefraction of their African ancestry: “Black,” “mulatto,” “quadroon” and “octoroon.”

“Mexican” was listed as its own race in1930, only to be removed the next decade.

It was in the year1970 that people were first allowed to choose their race, rather than having a census taker do so. This made the census a marker of self-identification instead of an outsider’s perception.

Thatsame year, a new question was added to assess the size of the Hispanic population. Mexican, Puerto Rican and Cuban advocates had pressed for the addition for years, arguing that a full accounting of the population was needed to ensure civil rights protections.

In 1997, the U.S. government setrace and ethnicity standards, which were applied to the2000 census and have largely remained in place.

The reality of categorizing people with distinct labels has never been simple.

People with identical lineage may choose different boxes, and the same person may choose different boxes in different years. Former President Barack Obama, the son of a white woman from Kansas and a Black man from Kenya, for example,marked himself as “Black,” even when checking more than one race was an option.

Historically, some edits to census race boxes reflected changes in policy or public sentiment. As the nation’s laws on slavery shifted, the census began phasing out the counting of enslaved people and instead introduced new terms to define the Black population.

Other changes were from a push and pull between how the government saw individuals and how they wanted to self-identify. Despite being banished from common use, theterm “Negro,” for example, was used in nine decennial censuses until 2010. The term was dropped by the next census.

With 24 decennial censuses so far, race options have changed more than a dozen times, as new groups have been added and others deleted.

“It’s like the census is adjusting the dials on your camera and you get different pictures accordingly,” said Naomi Mezey, a law professor at Georgetown University and the author of “Erasure and Recognition: The Census, Race and the National Imagination.” “It has huge and profound cultural consequences.”

Most recently, the census forms have become the most reliable path to becoming visible — a way to have respondents’ identity, or at least something close to it, documented.

How the Counting Started

Charting the changes in the census over the last two centuries shows the country’s continued struggles over racism, nativism and xenophobia. The census performs dual, and, at times, conflicting purposes: keeping close count of those who deviate from the majority and also recognizing the way people perceive their own racial and ethnic identities.

The1790 census did not explicitly specify the race of Black people or even acknowledge Native Americans.

1790 census

All

other

free

persons

Free white

males

Free white

females

Slaves

All

other

free

persons

Free

white

females

Free

white

males