Epidemiologic Features and Clinical Course of Patients Infected WithSARS-CoV-2 in Singapore

Barnaby Edward Young,MB, BChir

Sean Wei Xiang Ong,MBBS

Shirin Kalimuddin,MPH

Jenny G Low,MPH

Oon-Tek Ng,MPH

Kalisvar Marimuthu,MBBS

Thean Yen Tan,MBBCh

Mark I-Cheng Chen,PhD

Monica Chan,BMBS

Shawn Vasoo,MBBS

Boon Huan Tan,PhD

Raymond Tzer Pin Lin,MBBS

Vernon Jian Ming Lee,PhD

Yee-Sin Leo,MPH

David Chien Lye,MBBS

GroupInformation: Members of the Singapore 2019 Novel Coronavirus OutbreakResearch Team are listed in theSupplement.

Corresponding Authors: Barnaby EdwardYoung, MB, BChir (Barnaby_young@ncid.sg) and Yee-Sin Leo, MPH (Yee_Sin_Leo@ncid.sg), NationalCentre for Infectious Diseases, 16 Jln Tan Tock Seng, Singapore308442.

Accepted for Publication: February 27, 2020.

Published Online: March 3, 2020.doi:10.1001/jama.2020.3204

Correction: This article wascorrected online on March 20, 2020, for an incorrect medication dose in thetext, a typographic error in Figure 1, and an error in the authoraffiliations.

Author Contributions: Dr Younghad full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for theintegrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Concept and design: Young, Ong, O.-T. Ng, Marimuthu, Ang,Anderson, M. Chan, Vasoo, B. Tan, Leo, Lye.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Young, Ong,Kalimuddin, Low, S. Tan, Loh, O.-T. Ng, Marimuthu, Ang, Mak, Lau, Anderson, K.Chan, T. Tan, T. Ng, Cui, Said, Kurupatham, Chen, Wang, B. Tan, Lin, Lee, Leo,Lye.

Drafting of the manuscript: Young, Ong, Low, O.-T. Ng, Ang, Mak,Anderson, Said, Lee, Lye.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectualcontent: Young, Ong, Kalimuddin, Low, S. Tan, Loh, O.-T. Ng,Marimuthu, Lau, Anderson, K. Chan, T. Tan, T. Ng, Cui, Said, Kurupatham, Chen,M. Chan, Vasoo, Wang, B. Tan, Lin, Lee, Leo, Lye.

Statistical analysis: Young, Ang, Anderson, Said.

Obtained funding: Young, Marimuthu, Anderson, B. Tan.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Young, Ong, S.Tan, O.-T. Ng, Marimuthu, Mak, Lau, Anderson, K. Chan, T. Ng, Cui, Said,Kurupatham, Chen, M. Chan, Vasoo, Lin, Wang, B. Tan, Lee, Leo, Lye.

Supervision: Young, Kalimuddin, O.-T. Ng, Marimuthu, Anderson,T. Ng, M. Chan, Vasoo, Lin, Wang, B. Tan, Lee, Leo, Lye.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: DrYoung reported receiving personal fees from Sanofi and Roche. Dr Wang reportedreceiving grants from the Ministry of Health, Singapore. No other disclosureswere reported.

Funding/Support: Recruitment ofstudy participants and sample collection was funded by a seed grant from theSingapore National Medical ResearchCouncil (TR19NMR119SD [project CCGSFPOR20001]). Thepolymerase chain reaction work on nonrespiratory clinical samples was partiallysupported by grant NRF2016NRFNSFC002-013 (Combating the Next SARS-or MERS-LikeEmerging Infectious Disease Outbreak by Improving Active Surveillance).

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The Singapore National Medical ResearchCouncil had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection,management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, orapproval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript forpublication.

Additional Contributions: We thank all clinical and nursing staffwho provided care for the patients at National Centre for Infectious Diseases,Singapore General Hospital, Changi General Hospital, and Sengkang GeneralHospital; staff at the Communicable Diseases Division, Ministry of Health, forcontributing to outbreak response and contact tracing; staff at the NationalPublic Health and Epidemiology Unit, National Centre for Infectious Diseases,for assisting with data analysis; staff in the Singapore Infectious DiseaseClinical Research Network and Infectious Disease Research and Training Office,National Centre for Infectious Diseases, for coordinating patient recruitment;staff (especially Jin Phang Loh, PhD, Wee Hong Koh, BSc, Ai Sim Lim, BSc, XiaoFang Lim, BSc, and Chin Wen Liaw, BSc, at DSO National Laboratories) for BSL3laboratory work; staff at Duke NUS Medical School (especially Viji Vijayan,MBBS, Velraj Sivalingam, BSc, and Benson Ng, BSc, of the Duke-NUS ABSL3facility) for logistics management and assistance. None of these individualsreceived compensation for their role in the study.

Corresponding author.

Received 2020 Feb 20; Accepted 2020 Feb 27; Issue date 2020 Apr 21.

Key Points

Question

What was the initial experience in Singapore with the outbreak of severeacute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)?

Findings

In this descriptive case series of the first 18 patients diagnosed withSARS-CoV-2 infection in Singapore between January 23 and February 3, 2020,clinical presentation was a respiratory tract infection with prolonged viralshedding from the nasopharynx of 7 days or longer in 15 patients (83%).Supplemental oxygen was required in 6 patients (33%), 5 of whom were treatedwith lopinavir-ritonavir, with variable clinical outcomes followingtreatment.

Meaning

These findings provide clinical features and course among patients diagnosedwith SARS-CoV-2 infection in Singapore.

Abstract

Importance

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) emerged inWuhan, China, in December 2019 and has spread globally with sustainedhuman-to-human transmission outside China.

Objective

To report the initial experience in Singapore with the epidemiologicinvestigation of this outbreak, clinical features, and management.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Descriptive case series of the first 18 patients diagnosed with polymerasechain reaction (PCR)–confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection at 4 hospitals inSingapore from January 23 to February 3, 2020; final follow-up date wasFebruary 25, 2020.

Exposures

Confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Clinical, laboratory, and radiologic data were collected, including PCR cyclethreshold values from nasopharyngeal swabs and viral shedding in blood,urine, and stool. Clinical course was summarized, including requirement forsupplemental oxygen and intensive care and use of empirical treatment withlopinavir-ritonavir.

Results

Among the 18 hospitalized patients with PCR-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection(median age, 47 years; 9 [50%] women), clinical presentation was an upperrespiratory tract infection in 12 (67%), and viral shedding from thenasopharynx was prolonged for 7 days or longer among 15 (83%). Sixindividuals (33%) required supplemental oxygen; of these, 2 requiredintensive care. There were no deaths. Virus was detectable in the stool (4/8[50%]) and blood (1/12 [8%]) by PCR but not in urine. Five individualsrequiring supplemental oxygen were treated with lopinavir-ritonavir. For 3of the 5 patients, fever resolved and supplemental oxygen requirement wasreduced within 3 days, whereas 2 deteriorated with progressive respiratoryfailure. Four of the 5 patients treated with lopinavir-ritonavir developednausea, vomiting, and/or diarrhea, and 3 developed abnormal liver functiontest results.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among the first 18 patients diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection in Singapore,clinical presentation was frequently a mild respiratory tract infection.Some patients required supplemental oxygen and had variable clinicaloutcomes following treatment with an antiretroviral agent.

This case series describes the epidemiologic features, clinical presentation,treatment, and outcomes of the first 18 patients with confirmed coronavirusdisease 2019 (COVID-19) in Singapore

Introduction

The third novel coronavirus in 17 years emerged in Wuhan,China, in December 2019.1Phylogenetics has indicated that severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2(SARS-CoV-2) is closely related to bat-derived SARS-like coronaviruses.2 Early reports from Wuhandescribed the associated coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) as a SARS-like atypicalpneumonia in which 26% to 33% of patients required intensive care and 4% to 15%died.1,3,4 A large case series of 72 314infected individuals has since refined these initial estimates in China to severedisease in 14% and a case-fatality rate of 2.3%.5

On January 23, 2020, the first imported SARS-CoV-2 infection in Singapore wasdetected in a visitor from Wuhan. Subsequently, COVID-19 has been diagnosed amongother visitors and returning travelers, and from limited localtransmission.6

While a proven effective antiviral treatment in COVID-19 is not available, theantiretroviral drug lopinavir-ritonavir has been proposed, as its potentialeffectiveness in the treatment of SARS was suggested in 2 case series.7,8 In Middle East respiratory syndrome,lopinavir-ritonavir also showed potential activity in marmosets,9 but in a mouse model it didnot reduce virus titer or lung pathology, although it improved lungfunction.10

This case series describes the epidemiologic features, clinical presentation,treatment, and outcomes of the first 18 patients in Singapore with confirmedCOVID-19.

Methods

Outbreak Response

On January 2, 2020, after first reports of an outbreakof atypical pneumonia in Wuhan, China, the Singapore Ministry of Health issued ahealth alert that patients with pneumonia and recent travel to Hubei Provinceshould be screened for SARS-CoV-2 infection. All individuals with suspectedSARS-CoV-2 infection were isolated with airborne and contact precautions, andattending staff wore personal protective equipment in accordance with the USCenters for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines.11 Extensive contact tracing followed byquarantine of asymptomatic contacts and hospital isolation and screening ofsymptomatic contacts was strictly enforced.

Data and Specimen Collection

Individuals confirmed to have COVID-19 by SARS-CoV-2 real-time reversetranscriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) were eligible forinclusion in this study (eMethods in theSupplement). Data were collected at the 4hospitals that provided care for these patients.

Waiver of informed consent for collection of clinical data from infectedindividuals was granted by the Ministry of Health, Singapore, under theInfectious Diseases Act as part of the COVID-19 outbreak investigation. Writteninformed consent was obtained from study participants for collection ofbiological samples after review and approval of the study protocol by theinstitutional ethics committee.

Data from electronic health records were summarized using a standardized datacollection form. Two researchers independently reviewed the data collectionforms for accuracy.

Specimens (blood, stool, and urine samples; nasopharyngeal swabs) were collectedat multiple time points in the first 2 weeks following study enrollment andtested by RT-PCR for the presence of SARS-CoV-2. RT-PCR cycle threshold valueswere collected. The cycle threshold value correlates with the number of copiesof the virus in a biological sample, in an inversely proportional andexponential manner. Sequencing of PCR products of the RNA-dependent RNApolymerase (RdRp) gene were used to construct phylogenetictrees (eMethods in theSupplement).

Clinical Management

As part of standard of care, complete blood cell count, tests of kidney and liverfunction, and measurement of C-reactive protein and lactate dehydrogenase levelswere performed. Respiratory samples were tested for influenza and otherrespiratory viruses with a multiplex PCR assay.

All patients received supportive therapy, including supplemental oxygen whensaturations as measured by pulse oximeter dropped below 92%. Patients clinicallysuspected of having community-acquired pneumonia were administered empiricalbroad-spectrum antibiotics and oral oseltamivir. Coformulatedlopinavir-ritonavir (400 mg/100 mg twice daily orally for up to 14 days) wasprescribed to selected patients at the treating physicians’ discretionafter shared decision-making and provision of oral informed consent.Corticosteroids were avoided, reflecting increased mortality with their use insevere influenza.12

Respiratory samples were sent daily for SARS-CoV-2 PCR on clinical recovery.Deisolation was contingent on at least 2 consecutive negative PCR assay resultsmore than 24 hours apart.

Results

Epidemiologic Features

Between January 23 and February 3, 2020, 18 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2were diagnosed in Singapore, with symptom onset from January 14 to January 30,2020. All patients reported travel to Wuhan, China, in the 14 days prior toillness onset (eTable 1 in theSupplement). Four patients (22%) wereidentified through contact tracing, while 3 (17%) were identified through borderscreening. Of the 18 patients, 16 (89%) were Chinese nationals, while 2 (11%)were Singapore residents. There were 5 clusters comprising family, travelingcompanions, or other close contacts (eFigure 1 in theSupplement). Contact tracing of the 18 patients identified a total of264 close contacts in Singapore (eFigure 2 in theSupplement). As of February 25, 2020, no infections had been detectedamong health care workers involved in the care of patients with COVID-19.

Clinical Features

Clinical features are summarized in theTable. Fever (13 [72%]), cough (15 [83%]), and sore throat (11[61%]) were common symptoms. Rhinorrhea was infrequent (1 [6%]), while 6patients (33%) had an abnormal chest radiograph finding or lung crepitations. Nopatients presented with a severe acute respiratory distress syndrome, and only 1required immediate supplemental oxygen. Lymphopenia (<1.1×109/L) was present in 7 of 16 patients (39%) and anelevated C-reactive protein level (>20 mg/L) in 6 of 16 (38%), while kidneyfunction remained normal.

Table. Clinical Features of Patients Infected With SARS-CoV-2.

| All patients(N = 18) | Did not requiresupplemental O2 (n = 12) | Required supplementalO2 (n = 6) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, median (range)y | 47 (31-73) | 37 (31-56) | 56 (47-73) |

| Male sex, No. (%) | 9 (50) | 7 (58) | 2 (33) |

| Any comorbidity, No.(%)a | 5 (28) | 1 (8) | 4 (67) |

| Signs and symptoms onpresentation, No. (%) | |||

| Fever | 13 (72) | 7 (58) | 6 (100) |

| Cough | 15 (83) | 10 (83) | 5 (83) |

| Shortness of breath | 2 (11) | 1 (8) | 1 (17) |

| Rhinorrhea | 1 (6) | 1 (8) | 0 |

| Sore throat | 11 (61) | 8 (67) | 3 (50) |

| Diarrhea | 3 (17) | 3 (25) | 0 |

| Vital signs atpresentation, median (range) | |||

| Temperature, °C | 37.7 (36.1-39.6) | 38.3 (36.6-39.6) | 37.7 (36.1-38.1) |

| Respiratory rate,breaths/min | 18 (16-21) | 18 (17-19) | 20 (16-21) |

| Pulse oximeterO2 saturation, % | 98 (95-100) | 98 (95-100) | 97 (95-98) |

| Systolic blood pressure,mm Hg | 131 (103-167) | 131 (104-167) | 136 (103-141) |

| Heart rate, /min | 97 (75-118) | 99 (75-118) | 91 (78-102) |

| Baseline investigations,median (range) | |||

| WBCs,×109/L | 4.6 (1.7-6.3) | 4.6 (1.7-6.3) | 3.4 (2.6-5.8) |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 13.5 (11.7-17.2) | 13.9 (11.7-17.2) | 13.2 (11.7-14) |

| Platelets,×109/L | 159 (116-217) | 159 (128-213) | 156 (116-217) |

| Neutrophils,×109/L | 2.7 (0.7-4.5) | 2.8 (0.7-4.5) | 1.8 (1.2-3.7) |

| Lymphocytes,×109/L | 1.2 (0.8-1.7) | 1.2 (0.8-1.6) | 1.1 (0.8-1.7) |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L(n = 16) | 16.3 (0.9-97.5) | 11.1 (0.9-19.1) | 65.6 (47.5-97.5) |

| LDH, U/L(n = 13) | 512 (285-796) | 424 (285-748) | 550 (512-796) |

| Abnormal chestradiograph, No. (%) | 6 (33) | 3 (25) | 3 (50) |

| Duration of symptoms,median (range) | |||

| Fever, d | 4 (0-15) | 1 (0-7) | 5 (4-15) |

| Any symptoms, d | 13 (5-24) | 12 (5-24) | 16 (10-20) |

Abbreviations: LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; SARS-CoV-2, severe acuterespiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; WBC, white blood cell.

SI conversion factor: To convert LDH values to μkat/L, multiply by0.0167.

Group not requiring supplemental oxygen: hypertension, diabetes.Group requiring supplemental oxygen: hypertension(n = 4), type 2 diabetes (n = 1),hyperlipidemia (n = 1).

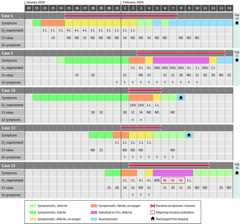

The clinical course was uncomplicated for 12 patients (67%), but 6 patients (33%)desaturated and required supplemental oxygen (Figure 1). Chest radiographs showed no pulmonaryopacities at presentation in 12 patients (67%) and remained clear throughout theacute illness in 9 (50%). Three patients with initially normal chest radiographfindings developed bilateral diffuse airspace opacities; of these, 2 had beenpersistently febrile for more than 1 week. Two individuals (11%) requiredadmission to the intensive care unit because of increasing supplemental oxygenrequirements, and 1 (6%) required mechanical ventilation. No concomitantbacterial or viral infections were detected, and there were no deaths as ofFebruary 25, 2020.

Figure 1. Time Course of Symptoms, Supplemental Oxygen Requirements, HospitalAdmission, and Discharge of Patients Infected With SARS-CoV-2.

ICU indicates intensive care unit; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Clinical Outcomes

Of the 6 patients who required supplemental oxygen, 5 receivedlopinavir-ritonavir (Figure 2).For 3 of 5 patients (60%), initiation of lopinavir-ritonavir was followed by areduction in supplemental oxygen requirements within 3 days, and viral sheddingin nasopharyngeal swabs cleared within 2 days of treatment for 2 of 5 (40%).

Figure 2. Clinical Progress in Patients Treated WithLopinavir-Ritonavir.

Cycle threshold (Ct) value corresponds to the number of copies of thevirus in a biological sample, in an inversely proportional andexponential manner. ICU indicates intensive care unit; GI,gastrointestinal; ND, not detected; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratorysyndrome coronavirus 2; Y, yes; Vt, mechanical ventilation.

Two patients, however, deteriorated and experienced progressive respiratoryfailure while receiving lopinavir-ritonavir, with 1 requiring invasivemechanical ventilation. Virus continued to be detected by nasopharyngeal swab orendotracheal tube aspirate for these 2 patients for the duration of theiradmission to intensive care.

Four of the 5 patients treated with lopinavir-ritonavir developed nausea,vomiting, and/or diarrhea, and 3 developed abnormal liver function test results.Only 1 individual completed the planned 14-day treatment course as a result ofthese adverse events.

Virologic Features

Median duration of viral shedding from first to last positive nasopharyngeal swabcollected as part of clinical care was 12 days (range, 1-24), and 15 patients(83%) had viral shedding from the nasopharynx detected for 7 days or longer.Daily serial RT-PCR cycle threshold values for all 18 patients are shown ineFigure 3 in theSupplement. The time course of serial cyclethreshold values by day of illness for 12 patients not receiving supplementaloxygen and 6 patients receiving supplemental oxygen (of whom 5 were treated withlopinavir-ritonavir) appeared similar (eFigure 4 in theSupplement).

Virus was detected by PCR in stool (4/8 patients [50%]) and in whole blood (1/12[8%]); virus was not detected in urine (0/10 samples) (eTable 2 in theSupplement). Viral culture results were not available at the time ofwriting to determine the viability of virus detected outside the respiratorytract.

Sequences for phylogenetic analysis were available for 6 viruses (eFigure 5 intheSupplement). All clustered together with other SARS-CoV-2 sequencesreported from China and other countries and are available in publicdatabases.

Discussion

This descriptive case series reports the clinical features of the first 18 patientswith laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in Singapore, reporting epidemiologicfeatures and clinical course in detail.

Perhaps reflecting the intensive efforts at contacttracing, 28% of patients were without fever vs 1.4% to 17% in 3 previously reportedstudies from Wuhan, China.1,4,13 In the current study, 6of 18 patients (33%) experienced oxygen desaturation to 92% or less, in contrast tothe 76% to 90% supplemental oxygen use from the other 3 studies.1,4,13

In 4 of 8 patients, virus was detected in stool, regardless of diarrhea, over 1 to 7days. Viremia was detected in 6 patients1 and 1 of 5 patients14 in China but only in 1 of 12 in thisstudy. In the family cluster in Shenzhen, the virus was not detected in urine orstool.14 In SARS,viremia was observed in the first week, with peak respiratory viral shedding in thesecond week and persistent stool viral shedding beyond the second week.15 In Middle Eastrespiratory syndrome, viral shedding was greater in lower respiratory tract samplesthan in blood and stool.16 Viral load in nasopharyngeal samples and viremia was associatedwith disease severity in SARS.17

In this study, viral load in nasopharyngeal samples frompatients with COVID-19 peaked within the first few days after symptom onset beforedeclining. The duration of viral shedding from nasopharyngeal aspirates wasprolonged up to at least 24 days after symptom onset. This was longer than reportedfrom a comparable series from China.18 Toward the end of this period virus was only intermittentlydetected from nasopharyngeal swabs. It is unclear whether this is attributable tobiological differences in the intensity of shedding or to sampling variability whenlow amounts of virus are present. Determining whether the virus remainstransmissible throughout the period of detectability is critical to controlefforts.

Five patients were treated with lopinavir-ritonavir within1 to 3 days of desaturation, but evidence of clinical benefit was equivocal. Whiledefervescence occurred within 1 to 3 days of lopinavir-ritonavir initiation, it wasunable to prevent progressive disease in 2 patients. Decline in viral load asindicated by the cycle threshold value from nasopharyngeal swabs also appearedsimilar between those treated and not treated with lopinavir-ritonavir. Theeffectiveness of lopinavir-ritonavir treatment in COVID-19 needs to be examined inan outbreak randomized trial, given a lack of clear signal in this small caseseries.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it was a case series of 18 patientswho acquired their infection following travel to Wuhan, China. Findings fromthis study are valuable early data from a high-resource setting but may changeas this outbreak continues to evolve and local transmission clusters emerge.Second, 9 individuals (50%) presented to the hospital more than 2 days aftersymptom onset. As a result, sample collection early during the course of illnesswas limited. Third, biological samples were collected systematically whenpossible, but not all patients consented to sample collection. Baselinelaboratory data were also not available for all patients. Fourth, cyclethreshold values are a quantitative measure of viral load, but correlation withclinical progress and transmissibility is not yet known.

Conclusions

Among the first 18 patients diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection in Singapore,clinical presentation was frequently a mild respiratory tract infection. Somepatients required supplemental oxygen and had variable clinical outcomes followingtreatment with an antiretroviral agent.

eMethods. Diagnostic Testing and RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase (RdRp)Sequencing of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)From Nasopharyngeal Samples

eFigure 1. Case Map of Confirmed 2019-nCoV Cases in Singapore

eFigure 2. Workflow of Screening and Admission for Suspected COVID-19 (as ofFebruary 8, 2020).

eFigure 3A. Individual Plot of Serial Cycle Threshold (Ct) Values by Day ofIllness for Each Patient

eFigure 3B. Serial Cycle Threshold Values for All Patients by Day ofIllness

eFigure 4. Serial Cycle Threshold (Ct) Values by Day of Illness up to Day 14,Split by Patients Who (A) Required Supplemental Oxygen and (B) Did NotRequire Supplemental Oxygen

eFigure 5. Phylogenetic Tree of Six Patients With Available Sequences

eTable 1. Epidemiologic Features of Patients Infected With 2019-nCoV

eTable 2. Cycle Threshold Values for Respiratory, Blood, Urine, and StoolSamples by Day of Illness

eTable 3. Singapore 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak Research Team Members

eReferences

References

- 1.Huang C,Wang Y,Li X, et al.Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novelcoronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet.2020;395(10223):497-506.doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu R,Zhao X,Li J, et al.Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novelcoronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptorbinding. Lancet.2020;395(10224):565-574.doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu N,Zhang D,Wang W, et al. ; China NovelCoronavirus Investigating and Research Team .A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China,2019. N Engl J Med.2020;382(8):727-733.doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang D,Hu B,Hu C, et al.Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China.JAMA. Published online February 7, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu Z,McGoogan JM.Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirusdisease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control andPrevention. JAMA. Published online February24, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong JEL,Leo YS,Tan CC.COVID-19 in Singapore—current experience: criticalglobal issues that require attention and action.JAMA. Published online February 20, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan KS,Lai ST,Chu CM, et al.Treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome withlopinavir/ritonavir: a multicentre retrospective matched cohortstudy. Hong Kong Med J.2003;9(6):399-406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chu CM,Cheng VC,Hung IF, et al. ; HKU/UCHSARS Study Group . Role oflopinavir/ritonavir in the treatment of SARS: initial virological andclinical findings. Thorax.2004;59(3):252-256.doi: 10.1136/thorax.2003.012658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan JF,Yao Y,Yeung ML, et al.Treatment with lopinavir/ritonavir or interferon-β1bimproves outcome of MERS-CoV infection in a nonhuman primate model of commonmarmoset. J Infect Dis.2015;212(12):1904-1913.doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheahan TP,Sims AC,Leist SR, et al.Comparative therapeutic efficacy of remdesivir andcombination lopinavir, ritonavir, and interferon beta againstMERS-CoV. Nat Commun.2020;11(1):222.doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13940-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Interim infection prevention and controlrecommendations for patients with known or patients under investigation for 2019novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in a healthcare setting. Centers for DiseaseControl and Prevention. Updated February 21, 2020. AccessedFebruary 27, 2020.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/hcp/infection-control.html

- 12.Lansbury LE,Rodrigo C,Leonardi-Bee J,Nguyen-Van-Tam J, ShenLim W.Corticosteroids as adjunctive therapy in the treatment ofinfluenza: an updated Cochrane systematic review andmeta-analysis. Crit Care Med.2020;48(2):e98-e106.doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen N,Zhou M,Dong X, et al.Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptivestudy. Lancet.2020;395(10223):507-513.doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan JF,Yuan S,Kok KH, et al.A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of afamily cluster. Lancet.2020;395(10223):514-523.doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peiris JS,Chu CM,Cheng VC, et al. ; HKU/UCHSARS Study Group . Clinicalprogression and viral load in a community outbreak of coronavirus-associatedSARS pneumonia: a prospective study.Lancet.2003;361(9371):1767-1772.doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13412-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oh MD,Park WB,Choe PG, et al.Viral load kinetics of MERS coronavirusinfection. N Engl J Med.2016;375(13):1303-1305.doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1511695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hung IF,Cheng VC,Wu AK, et al.Viral loads in clinical specimens and SARSmanifestations. Emerg Infect Dis.2004;10(9):1550-1557.doi: 10.3201/eid1009.040058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zou L,Ruan F,Huang M, et al.SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens ofinfected patients. N Engl J Med. Publishedonline February 19, 2020. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Diagnostic Testing and RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase (RdRp)Sequencing of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)From Nasopharyngeal Samples

eFigure 1. Case Map of Confirmed 2019-nCoV Cases in Singapore

eFigure 2. Workflow of Screening and Admission for Suspected COVID-19 (as ofFebruary 8, 2020).

eFigure 3A. Individual Plot of Serial Cycle Threshold (Ct) Values by Day ofIllness for Each Patient

eFigure 3B. Serial Cycle Threshold Values for All Patients by Day ofIllness

eFigure 4. Serial Cycle Threshold (Ct) Values by Day of Illness up to Day 14,Split by Patients Who (A) Required Supplemental Oxygen and (B) Did NotRequire Supplemental Oxygen

eFigure 5. Phylogenetic Tree of Six Patients With Available Sequences

eTable 1. Epidemiologic Features of Patients Infected With 2019-nCoV

eTable 2. Cycle Threshold Values for Respiratory, Blood, Urine, and StoolSamples by Day of Illness

eTable 3. Singapore 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak Research Team Members

eReferences