Prediction and estimation of effective population size

E Santiago

A Caballero

Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, Regent's Park, London NW1 4RY, UK. E-mail:jinliang.wang@ioz.ac.uk

Received 2015 Sep 29; Revised 2016 May 3; Accepted 2016 May 16; Issue date 2016 Oct.

Abstract

Effective population size (Ne) is a key parameter in population genetics. It has important applications in evolutionary biology, conservation genetics and plant and animal breeding, because it measures the rates of genetic drift and inbreeding and affects the efficacy of systematic evolutionary forces, such as mutation, selection and migration. We review the developments in predictive equations and estimation methodologies of effective size. In the prediction part, we focus on the equations for populations with different modes of reproduction, for populations under selection for unlinked or linked loci and for the specific applications to conservation genetics. In the estimation part, we focus on methods developed for estimating the current or recent effective size from molecular marker or sequence data. We discuss some underdeveloped areas in predicting and estimatingNe for future research.

Introduction

The concept of effective population size, introduced by SewallWright (1931,1933), is central to plant and animal breeding (Falconer and Mackay, 1996), conservation genetics (Frankhamet al., 2010;Allendorfet al., 2013) and molecular variation and evolution (Charlesworth and Charlesworth, 2010), as it quantifies the magnitude of genetic drift and inbreeding in real-world populations. A substantial number of extensions to the basic theory and predictions were made since the seminal work of Wright, with main early developments by James Crow and Motoo Kimura (Kimura and Crow, 1963a;Crow and Kimura, 1970) and later by a list of contributors. Several review papers (Crow and Denniston, 1988;Caballero, 1994;Wang and Caballero, 1999;Nomura, 2005a) and population genetic books (Fisher, 1965;Wright, 1969;Ewens, 1979;Nagylaki, 1992) have summarised the existing theory in predicting the effective size of a population at different spatial and timescales under various inheritance modes and demographies. Comparatively, methodological developments (reviewed bySchwartzet al., 1999;Beaumont, 2003a;Wang, 2005;Palstra and Ruzzante, 2008;Luikartet al., 2010;Gilbert and Whitlock, 2015) in estimating the effective size of natural populations from genetic data lag behind but are accelerating in the past decade, thanks to the rapid developments of molecular biology.

The classical developments of effective population size theory are based on the rate of change in gene frequency variance (genetic drift) or the rate of inbreeding. The effective population size is defined in reference to the Wright–Fisher idealised population, that is, a hypothetical population with very simplifying characteristics where genetic drift is the only factor in operation, and the dynamics of allelic and genotypic frequencies across generations merely depend on the population census (N) size. The effective size of a real population is then defined as the size of an idealised population, which would give rise to the rate of inbreeding and the rate of change in variance of gene frequencies actually observed in the population under consideration, which correspond to the so-called inbreeding and variance effective sizes, respectively (Crow and Kimura, 1970).

Predictions of the effective population size can also be obtained from the largest nonunit eigenvalue of the transition matrix of a Markov Chain which describes the dynamics of allele frequencies. Such derived effective size is called as eigenvalue effective size (seeEwens, 1979, pp. 104–112), which is equivalent to the random extinction effective size (Crow, 1954; see alsoHaldane, 1939). The transition matrix can be written for many genetic models and is particularly useful for complex scenarios such as populations varying in size, having age structures or being subject to demographic changes (for example,Charlesworth, 2001;Pollak, 2002;Wang and Pollak, 2002;Engenet al., 2005). A less often used approach is that for the mutation effective size, defined by the probability of identity in state of genes rather than identity by descent under an infinite allele model of mutations with a defined mutation rate (Whitlock and Barton, 1997).

Later developments based on coalescence theory (Wakeley, 2008) have also proved to be useful in the prediction of effective population size, particularly in the evolutionary context for predicting genetic variability at the molecular level (Charlesworth, 2009;Nicolaisen and Desai, 2012,2013). The coalescence theory states that the chance of coalescence of any two random gene copies in one generation time is 1/2N, which is the same as the rate of increase in identity by descent occurred from one generation to the next one. Thus, the probability of coalescencet generations ago is (1−(1/2N))t−1(1/2N). Therefore, the average time of coalescence of two randomly chosen genes isT=2N. The coalescent effective population size refers to the expected time of coalescenceT, in generations, of gene copies such thatT=2Ne (Nordborg and Krone, 2002;Wakeley and Sargsyan, 2009).

In this paper, we present a general overview of the main developments for predicting the effective population size (Ne). The review does not attempt to be exhaustive, and some of the material mentioned in previous reviews will not be repeated. We mainly focus on populations with different modes of reproduction, populations under selection and populations under genetic management in captive breeding conservation programmes, complementing previous reviews and adding material not covered or only partially covered by them. We also review the developments in estimating contemporary effective sizes from genetic marker data, focussing on the estimation principles and ignoring the technical details that were covered in the original papers. The underlying assumptions, application scopes, robustness and accuracies of different estimation methods are discussed and compared.

Prediction of the effective population size

In this section, we will summarise the main predictive equations for the asymptotic effective population size reached after a number of generations in a regular breeding system. In this case, all of the above approaches generally lead to the same predictive equations ofNe, except for a few particular scenarios. For example, in a regular breeding system for an undivided population the asymptotic inbreeding and variance effective sizes converge. Only in situations such as when the population is subdivided permanently in independent sublines with completely independent pedigrees (Wang, 1997a,b) or when the population is decreasing or increasing in size, these types ofNe will differ permanently. In fact, many of the equations shown below have been derived by two or more of the above approaches, and we will only mention some of these. For clarity and a better understanding of the main principles, several simplifying assumptions will also be made in this prediction section. Unless otherwise stated, we will assume that populations do not change size through time and are large enough so that second-order terms of 1/Ne can be safely ignored. These terms are generally of little relevance but make the derivations and theNe equations rather cumbersome. Finally, a single undivided population with discrete generations under a regular breeding scheme will be generally assumed unless otherwise indicated, so that prediction equations refer to asymptotic (Caballero, 1994) effective population sizes.

Populations with different modes of reproduction

As a starting point, we consider the simple equation derived byWright (1938), which takes account of the variance of the contributions from parents to progeny in a population of constant sizeN,

in a population of constant sizeN,

|

This expression also assumes a population either containing only hermaphrodites or comprising equal numbers of males and females, diploid autosomal inheritance and random mating (including selfing for hermaphrodites). InEquation (1), the term accounts for the genetic drift caused by the variable contributions among parents, whereas the first term ‘2' in the denominator accounts for the genetic drift caused by the Mendelian segregation of heterozygotes (that is, the drift in allele frequency arising from the fact that the progeny from a heterozygote can alternatively receive one or the other allele). It can also be seen as the variance in contributions between paternal and maternal genes at a locus within an individual or part of the variance in contribution between grandparents (the termδ2 inEquation (2) ofWang and Hill (2000)).

accounts for the genetic drift caused by the variable contributions among parents, whereas the first term ‘2' in the denominator accounts for the genetic drift caused by the Mendelian segregation of heterozygotes (that is, the drift in allele frequency arising from the fact that the progeny from a heterozygote can alternatively receive one or the other allele). It can also be seen as the variance in contributions between paternal and maternal genes at a locus within an individual or part of the variance in contribution between grandparents (the termδ2 inEquation (2) ofWang and Hill (2000)).

An illustrative generalisation ofEquation (1) to the case of different numbers of males (Nm) and females (Nf) is

|

with

|

where is the variance of the number of offspring of sexy from parents of sexx andSxm,xf is the covariance of the numbers of male and female offspring from parents of sexx.Equation (2) is the same as that derived byHill (1979), although it is expressed in a different form. It reduces to the classical equation ofWright (1933,1939) for a Poisson distribution of progeny number (that is,

is the variance of the number of offspring of sexy from parents of sexx andSxm,xf is the covariance of the numbers of male and female offspring from parents of sexx.Equation (2) is the same as that derived byHill (1979), although it is expressed in a different form. It reduces to the classical equation ofWright (1933,1939) for a Poisson distribution of progeny number (that is, for sexx,y=m,f),

for sexx,y=m,f),

|

which shows that unequal numbers of males and females in a population introduce a systematic variance in contribution between male and female parents and thus a reduction in effective size.

Predictive formulae for the effective size of X-linked genes were originally given byWright (1933) and later extended by other authors (seeCaballero, 1995). Later developments have also been made for Y-linked and maternally transmitted genes (Charlesworth, 2001;Laporte and Charlesworth, 2002;Evans and Charlesworth, 2013).

The generalisation ofEquation (1) to the case of a partially selfed population (in which there is partial selfing with proportionβ, random mating otherwise) is

|

(Crow and Morton, 1955), where

|

(Haldane, 1924) quantifies the deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium or the correlation of genes within individuals relative to the genes taken at random from the population (Wright, 1969). The value ofα in a large random mating population is approximately 0 (slightly negative when second-order terms are considered; seeEquation (23) below andWang, 1996a). For the case of biparental inbreeding such as partial full-sib mating in dioecious species, the expression is the same asEquation (5) except that the term (1+α) should be replaced by (1+3α) (Caballero and Hill, 1992). The equilibrium value ofα for biparental inbreeding is also different fromEquation (6) (for example,Ghai, 1969).

The generalisation ofEquation (5) for different numbers of males and females was made byWang (1996b), adding some covariance terms not considered byCaballero (1994) (Equation (17)). Equation byWang (1996b) also allows for different numbers of males and females varying over generations.

An excess of inbred matings (α>0 inEquation (5)) has the effect of increasing the correlation of genes within individuals and decreasing the frequency of heterozygotes by a factor ofα. It results in a decrease in the genetic drift owing to a decrease in Mendelian segregation variance and an increase in the genetic drift owing to an increase in the variance of contributions among individuals. Compared with random mating (α=0), whether an excess (α>0) or a deficit (α<0) of inbred matings may increase or decreaseNe depends on the variance in family size, . For the case of partial selfing (Equation (5)), inbreeding (α>0) increasesNe when

. For the case of partial selfing (Equation (5)), inbreeding (α>0) increasesNe when and decreasesNe when

and decreasesNe when . At exactly

. At exactly , selfing has no effect onNe.

, selfing has no effect onNe.

Predictions of the effective size for X-linked genes in non-random mating populations were given byWang (1996c).Nomura (2002a,2005b) also provided predictions of the effective size for a variety of mating systems in animals (see alsoBalloux and Lehmann (2003)). For example, for harem polygamy, where successful males generally mate with most or all of the females in their harem and the females generally mate with only one male, the effective size, for a Poisson distribution of progeny number, is better approximated by

|

rather than byEquation (4), showing the larger impact of male number for this type of mating system. Other predictions ofNe for different mating systems and overlapping generations have been provided byNunney (1993).

Equation (5) can also be obtained following the concept of long-term contributions from ancestors to descendants developed byWray and Thompson (1990) in the context of populations under selection. As suggested byWoolliams and Thompson (1994) and shown byCaballero and Toro (2000,2002), the expressions can be approximated by

|

whereV∞ is the variance of long-term contributions from ancestors to descendants. For random mating (α=0),V∞=1 andNe=N, as expected.

For a proportionβ of partial selfing, ifα is not too close to 1 (Caballero and Toro, 2000), which, when substituted intoEquation (8), givesEquation (5). When the numbers of selfed and nonselfed progeny are independently Poisson distributed,

ifα is not too close to 1 (Caballero and Toro, 2000), which, when substituted intoEquation (8), givesEquation (5). When the numbers of selfed and nonselfed progeny are independently Poisson distributed, (seeNomura, 1999a for a more precise prediction), and bothEquations (5) and(8) reduce to

(seeNomura, 1999a for a more precise prediction), and bothEquations (5) and(8) reduce to

|

(Li, 1976, p. 562;Pollak, 1987;Caballero and Hill, 1992;Nordborg and Krone, 2002). For a population with Poisson distribution of family size and complete selfing,Equation (9) reduces toNe=N/2.Equation (8) can also be applied to the scenario of partial full-sib mating with the appropriate approximation forV∞ (Caballero and Toro, 2000).

Predictions of the effective size for populations with mixed sexual and asexual reproduction systems and discrete and overlapping generations have been developed byYonezawa (1997). Assuming a monoecious plant species carrying out asexual propagation with a proportionδ in a population of constant sizeN (that is, an average progeny number of one and two for asexual propagation and sexual reproduction, respectively),Equation (5) ofYonezawa (1997) can be rearranged to

|

where is the variance of the number of asexually produced progeny among plants. If there is no asexual reproduction (δ=0),Equation (10) reduces toEquation (5), as it should. If all reproduction is asexual (δ=1),Equation (10) reduces to

is the variance of the number of asexually produced progeny among plants. If there is no asexual reproduction (δ=0),Equation (10) reduces toEquation (5), as it should. If all reproduction is asexual (δ=1),Equation (10) reduces to

|

Interestingly, if the number of asexually produced progeny is Poisson distributed , the expression is the same as for a sexually reproducing partially selfed population where the numbers of selfed and nonselfed progeny are independently Poisson distributed, that is,Equation (9). If all individuals are homozygotes (α=1),Ne=N/2, the same as for a fully selfed population.

, the expression is the same as for a sexually reproducing partially selfed population where the numbers of selfed and nonselfed progeny are independently Poisson distributed, that is,Equation (9). If all individuals are homozygotes (α=1),Ne=N/2, the same as for a fully selfed population.

An extension ofEquation (10) to overlapping generations was also given byYonezawa (1997).Equation (10) assumes that sexual and asexual contributions are independent. Predictions relaxing this assumption and extensions to more complex models were given byYonezawaet al. (2000,2004). Analytical expressions for these models of mixed sexual and asexual species were also given byOrive (1993) andBallouxet al. (2003) using coalescence theory.

Predictions of effective size for haplo–diploid species can generally be made by the standard formula for sex-linked genes (see review byCaballero, 1994). Some situations occur, however, where reproduction of these species is more complex than assumed by the simplest models. For example, in many eusocial Hymenoptera species, males can be produced by workers rather than only by queens. Predictions ofNe for this scenario have been developed byNomura and Takahashi (2012).

Populations under selection

In the absence of selection or when selection acts on a non-inherited trait, the effective size is simply a function of the variance of the number of offspring per parent, as inEquation (5). However, predictions ofNe are more complicated when selection acts on an inherited trait, such as when artificial selection is carried out for a quantitative trait in animal or plant breeding, or when natural selection acts on fitness traits against deleterious mutations or in favour of advantageous ones. In these scenarios, the drift process is amplified over generations because the random associations originated in a given generation between neutral and selected genes remain in descendants for a number of generations until they are eliminated by segregation and recombination. This problem was first addressed byRobertson (1961) and later on by other authors (for example,Wray and Thompson, 1990;Woolliamset al., 1993;Santiago and Caballero, 1995) for directional selection in quantitative traits. Extensions of the model were made later for populations under natural selection, linkage, overlapping generations and animal breeding schemes, as will be reviewed below.

Selection assuming unlinked genes

When selection acts on an inherited trait, changes in gene frequency at a focal neutral locus are positively correlated over generations because the selective values randomly associated with the neutral locus are not completely removed by segregation and recombination from one generation to the next. For unlinked genes and weak selection, the random association generated by sampling in a single generation is halved in consecutive generations by segregation and recombination. Therefore, the accumulative selective association has a limiting value times the value of the original random association (Robertson, 1961), and the corresponding variance of the long-term contributions of copies of the neutral gene will increase by a factorQ2. With regards to drift, the effective variance of contributions of individuals (with average 2) increases owing to selection by the same factor up to 4Q2C2, where the termC2 is the genetic variance of the individual trait measures (for the quantitative trait subject to artificial selection or fitness-related traits in the case of natural selection) relative to the mean of the trait in the population. This variance has to be added to the expected variance of random contributions not caused by selection

times the value of the original random association (Robertson, 1961), and the corresponding variance of the long-term contributions of copies of the neutral gene will increase by a factorQ2. With regards to drift, the effective variance of contributions of individuals (with average 2) increases owing to selection by the same factor up to 4Q2C2, where the termC2 is the genetic variance of the individual trait measures (for the quantitative trait subject to artificial selection or fitness-related traits in the case of natural selection) relative to the mean of the trait in the population. This variance has to be added to the expected variance of random contributions not caused by selection to predict the total variance of contributions. In reality, the associations are also reduced each generation to a proportion equal to the fraction of genetic variance remaining after selection (G), which, in turn, can be increased by the correlation between the selective advantages of male and female parents (r), and the series becomes

to predict the total variance of contributions. In reality, the associations are also reduced each generation to a proportion equal to the fraction of genetic variance remaining after selection (G), which, in turn, can be increased by the correlation between the selective advantages of male and female parents (r), and the series becomes

|

(Santiago and Caballero, 1995). In the case of partial selfing (or partial full-sib mating), the termr inEquation (12) should be replaced byβ (the proportion of inbred matings), because the correlation between the expected selective values of males and females (r) is approximately 1 for inbred matings (which take place with proportionβ) and approximately 0 for non-inbred matings, that is,Q=2/(2−G(1+β)).

Therefore, the equation accounting for selection as an extension ofEquation (5) is

|

Nomura (1999b,2005a) showed thatEquation (13), obtained by a genetic drift approach, could also be derived from an inbreeding approach by considering the variance of long-term contributions as used byWray and Thompson (1990) andWrayet al. (1990), when appropriate corrections are made in the latter (see alsoWoolliams and Bijma, 2000).

The application to different numbers of males and females was given bySantiago and Caballero (1995). That equation, however, lacked the same covariances as the equation without selection, as shown byNomura (1997a) andWang (1998). For random mating (α=0) and Poisson distribution of family sizes ,Equation (13) reduces to the simplest expression (Robertson, 1961),

,Equation (13) reduces to the simplest expression (Robertson, 1961),

|

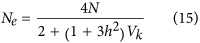

Equation (14) can be expressed in terms of heritability (h2) of fertility, as shown byNei and Murata (1966) andNomura (2002b). LetVk be the observed variance of family sizes, which would be if the decay in the cumulative effect of selection is ignored (that is,Q=2). The first term,

if the decay in the cumulative effect of selection is ignored (that is,Q=2). The first term, , is the non-heritable component of this variance, and the second term, 4C2=Vkh2, is the heritable component. Thus substituting these intoEquation (14) yields

, is the non-heritable component of this variance, and the second term, 4C2=Vkh2, is the heritable component. Thus substituting these intoEquation (14) yields

|

(Nei and Murata, 1966). The extension ofEquation (15) to dioecious populations was developed byNei and Murata (1966) assuming random union of gametes. A more general equation was developed byNomura (2002b), who also suggested a form of the equation that avoids estimating the heritability,

|

wherecovk,f andcovk,m are the offspring–mother and offspring–father covariances of sibship size, respectively.

The prediction of effective population size under selection with overlapping generations was considered byNomura (1996) andBijmaet al. (2000). As for the non-selection case (Hill, 1979),Ne is the same as that for populations with discrete generations having the same non-selective and selective components of variance in lifetime progeny numbers and the same number of individuals entering the population each generation. Another interesting result is that the average age of parents in populations under selection is smaller than that in populations under no selection, as, in the former, younger parents tend to have higher selective advantages.

Genetic marker data can be used to assist selection (that is, marker-assisted selection (MAS)) for a quantitative trait.Nomura (2000) investigated the predictive equation ofNe in this scenario and showed that it depends on the relative values of the genetic (r, 0.5 for full-sib families) and phenotypic (t) correlation between family members, wheret≈h2/2+c2,h2 is the trait heritability andc2 is the fraction of the phenotypic variance owing to the shared common environments of family members. When an index (I) is considered using individual phenotype (P) and molecular marker (M) information with given weights, that is,I=BPP+BMM, the effective size with MAS is reduced relative to that for phenotypic selection alone (Equation (14)) whent<r and is increased whent>r.

The prediction of effective population size under index selection was addressed byWrayet al. (1994),Caballeroet al. (1996b) andNomura (1998b,2005a). Assume truncation selection is carried out based on an index selection of the individual phenotype (P) and the mean phenotype of its full-sib family (Pf, including the individual),I=Bw(P−Pf)+Bb(Pf), whereBw andBb are the corresponding selection weights. The effective size can then be predicted usingEquation (14), whereQ=2/(1+kBb) and , whereρI is the correlation of full sibs for the index values,ρA is the correlation of full sibs owing to the breeding value of the parents,k=i(i−x),i is the selection intensity andx is the truncation point in the standardised normal distribution. This predictive equation corrects a typographical error in a sign in the equation ofCaballeroet al. (1996b, p. 77). When the whole pedigree information is available, estimation of breeding values can be made by Best Linear Unbiased Prediction selection. Predictions of the effective size under this selection method were investigated byNomuraet al. (1999)Bijma and Woolliams (2000) andBijmaet al. (2001).

, whereρI is the correlation of full sibs for the index values,ρA is the correlation of full sibs owing to the breeding value of the parents,k=i(i−x),i is the selection intensity andx is the truncation point in the standardised normal distribution. This predictive equation corrects a typographical error in a sign in the equation ofCaballeroet al. (1996b, p. 77). When the whole pedigree information is available, estimation of breeding values can be made by Best Linear Unbiased Prediction selection. Predictions of the effective size under this selection method were investigated byNomuraet al. (1999)Bijma and Woolliams (2000) andBijmaet al. (2001).

Other extensions for the prediction of the effective population size under selection refer to sex-linked loci (Nomura, 1997b;Wang, 1998), gynodioecious species (that is, species which have both hermaphrodite and female individuals,Laporteet al., 2000), open nucleus schemes (Nomura, 1997c;Bijma and Woolliams, 1999) and selection on traits affected by maternal effects (Rönnegård and Woolliams, 2003).

Selection at linked loci

The above formulations predict the rates of inbreeding that are usually calculated by tracing paths in genealogies of individuals. However, the real rates of inbreeding are expected to be larger than those predictions when selection acts on a system of linked genes. The reason for this is that the two gene copies at a neutral locus in an individual have different probabilities of propagation to the next generation, because they are embedded in homologous chromosomes with different alleles at linked selected loci. The problem of predictingNe in populations under purifying selection with linkage (the background selection model;Charlesworth, 2013) was addressed byHudson and Kaplan (1995) andNordborget al. (1996) focussing on the effect of selection on nucleotide diversity, bySantiago and Caballero (1998) analysing the cumulative effect of selection over generations with a genetic drift approach (the Robertson effect) and byNicolaisen and Desai (2012,2013) using the coalescence theory. All these papers derived the same equation for the asymptoticNe, which is a function of the haploid deleterious mutation rateU, the effects of mutations and the lengthL of the whole-genome or genome segment given in Morgans,

|

This equation is the exponential version ofEquation (14), , which was derived from the multiplicative fitness model assumed under background selection. HereC2=Us is the variance for fitness and the cumulative term,Q, for a rate of recombinationc between the neutral and selected loci, is

, which was derived from the multiplicative fitness model assumed under background selection. HereC2=Us is the variance for fitness and the cumulative term,Q, for a rate of recombinationc between the neutral and selected loci, is (Santiago and Caballero, 1998). If the focal neutral locus is located in the middle of the genome segment and the selected loci are uniformly scattered, the average value of theQc2 terms over the segment isQ2=1/(s(s+L/2)). Substituting this andC2=Us inEquation (14), we obtainEquation (17).

(Santiago and Caballero, 1998). If the focal neutral locus is located in the middle of the genome segment and the selected loci are uniformly scattered, the average value of theQc2 terms over the segment isQ2=1/(s(s+L/2)). Substituting this andC2=Us inEquation (14), we obtainEquation (17).

It is important to note that this equation predicts the magnitude of drift or inbreeding in the long term. For the focal neutral allele, this magnitude is effectively reached after a number of generations counted since it first appeared by mutation. Until that moment, drift at the neutral locus is expected to increase with time. The increasing drift acting on neutral mutations in consecutive generations can be predicted by the partialNe(t) values for generationt forward in time that can be calculated using the partial cumulative terms (Santiago and Caballero, 1998). An equivalent conclusion was reached byNicolaisen and Desai (2012,2013) from the point of view of the coalescent process. The consecutiveNe(−t) values that predict the increasing probability of coalescence under selectiont generations backwards in time (thus the negative sign) reach an asymptotic value given byEquation (17) and the predictions of the partialNe values given by both methods, forward and backward, are exactly the same for any generationt,

(Santiago and Caballero, 1998). An equivalent conclusion was reached byNicolaisen and Desai (2012,2013) from the point of view of the coalescent process. The consecutiveNe(−t) values that predict the increasing probability of coalescence under selectiont generations backwards in time (thus the negative sign) reach an asymptotic value given byEquation (17) and the predictions of the partialNe values given by both methods, forward and backward, are exactly the same for any generationt,

|

Illustrations of the decline inNe(t) over generations are given in Figure 3 ofSantiago and Caballero (1998) and Figure 3 ofNicolaisen and Desai (2013). This shows that the distortion of coalescent genealogies under selection and the cumulative effect of selection over generations are both specular images of the same process. Moreover, the pattern of neutral variation in populations under selection can be predicted by accumulating the expected distributions of neutral mutations originated in all the previous generations with the corresponding consecutive effective sizes given by theNe(t) values (Santiago and Caballero, 1998;Nicolaisen and Desai, 2012,2013). This means that the intensity of genetic drift varies over mutations that occurred at different generations backward in time. Therefore, strictly speaking, there is not a singleNe value representing the intensity of the drift process and, consequently, the amount and spectrum of variation under selection, even in populations at mutation–selection–drift equilibrium.

If mutations are advantageous (selective sweep model), predictions are generally cumbersome, because the genetic variance at selected loci is a function of the gene frequencies. Moreover, the stochastic distribution of selective sweeps over time is far away from the constant flux of variation usually assumed to simplify derivations.Wiehe and Stephan (1993) andGillespie (2000) derived equations for the expected heterozygosity at neutral loci using a model in which recurrent favourable mutations pass quickly through the population to fixation, wiping out linked variation. The first key simplification in these derivations is that the time of fixation of favourable mutations is so short relative to the timescale of genetic drift that it can be considered as occurring instantaneously. The second simplification is that the rate of recovery of neutral variation after a selective sweep is very slow when compared with the rate of occurrence of the sweeps. The recurrent substitutions lead to a roughly constant level of neutral variation in a stochastic process that is often referred to as ‘genetic draft'. A simple solution forNe can be obtained by directly applying the concept of variance of long-term contributions to an evolutionary timescale:

|

(Gillespie, 2000), whereθ is the rate of selective sweeps andy is the final frequency of the neutral copy that was initially associated with the favourable mutation when it first appeared. The frequency of this neutral copy is expected to increase toNy copies after the sweep, and the frequency of each of the other 2N−1 copies is expected to be reduced to (1−y) copies. Therefore, the variance of the expected long-term contributions for a single selective sweep is about 2Ny2. As selective sweeps occur at a rateθ, the second term of the denominator inEquation (19) is the total variance of the expected long-term contributions, that is,Q2C2 inEquation (14).

Effective population size in conservation practices

The concept of effective size is key to conservation genetic practices, as it summarises the past history of the population regarding inbreeding and genetic drift and provides the prospects for the sustainability of the population if the current effective size is maintained in the future. The effective population size is directly related to the statistics widely used to monitor conservation breeding schemes, such as the number of genome equivalentsNge≈Ne/t (Lacy, 1995), wheret is the number of generations of management.

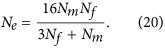

Minimising the loss of genetic variation is one of the main objectives of captive breeding programmes. This is achieved through minimising genetic drift and, therefore, maximisingNe. A classical strategy to follow is the equalisation of family sizes. By choosing one couple from each pair of parents, the variance of parental contributions is null , and fromEquation (1),Ne≈2N (Wright, 1938;Crow, 1954), which is twice the effective size of an unmanaged population with a Poisson distribution of family size. This is known as minimal inbreeding and it is the recommended procedure for applications in germplasm collection and regeneration in plants (see, for example,Vencovskyet al., 2012). However, effective sizes >2N can actually be obtained by population subdivision (Wright, 1943;Wang and Caballero, 1999) and other strategies, as shown below. The extension of the strategy in the case of different numbers of males and females was developed byGoweet al. (1959). In their selection scheme, each male contributes one son andrfm=Nf/Nm daughters, and each female contributes one daughter and has a probability ofNm/Nf of contributing one son. Thus

, and fromEquation (1),Ne≈2N (Wright, 1938;Crow, 1954), which is twice the effective size of an unmanaged population with a Poisson distribution of family size. This is known as minimal inbreeding and it is the recommended procedure for applications in germplasm collection and regeneration in plants (see, for example,Vencovskyet al., 2012). However, effective sizes >2N can actually be obtained by population subdivision (Wright, 1943;Wang and Caballero, 1999) and other strategies, as shown below. The extension of the strategy in the case of different numbers of males and females was developed byGoweet al. (1959). In their selection scheme, each male contributes one son andrfm=Nf/Nm daughters, and each female contributes one daughter and has a probability ofNm/Nf of contributing one son. Thus and all of the other variances and covariances inEquation (2) are 0. Substituting these intoEquations (2) and(3) gives

and all of the other variances and covariances inEquation (2) are 0. Substituting these intoEquations (2) and(3) gives

|

Compared with no selection (random Poisson distribution of the number of offspring per parent,Equation (4)), this scheme can increaseNe by a proportion of (rfm+3)/(3rfm+1). When the female/male ratio,rfm=Nf/Nm, is 2, for example,Ne is increased by 71.4%.

Wang (1997c) proposed an alternative design that produces further increases inNe of about 17% whenrfm=2. In this scheme, among therfm females mated with each male, one is selected at random to contribute one son and each of the remainingrfm−1 females contributes one daughter. In this scenario, is as forEquation (20), but

is as forEquation (20), but , and a negative covariance is induced between the numbers of male and female offspring from female parents,Sfm,ff=−Nm/Nf. Substituting these terms intoEquations (2) and(3),

, and a negative covariance is induced between the numbers of male and female offspring from female parents,Sfm,ff=−Nm/Nf. Substituting these terms intoEquations (2) and(3),

|

The benefit of this scheme over that fromGoweet al. (1959) is decreased asrfm gets larger. For sex-linked loci, a benefit is also produced if males are the heterogametic sex. The above equations refer to random mating of parents.Wang (1997c) also proposed a system of non-random mating in which each male is mated with one of the groups of half-sib females who are not sisters of the male. This is a sort of population subdivision where the half-sibs are like ‘subpopulations' and there is random migration of males and no migration of females among the ‘subpopulations' (seeWang and Caballero, 1999). The mating scheme can further increaseNe over that predicted byEquation (21).

Wang (1997c) method applies to a single generation.Sánchezet al. (2003) extended the method across generations to account for long-term contributions, further improving its efficiency. With the availability of pedigree or molecular marker information, a more general method, based on finding the contributions from parents to progeny that minimise the average coancestry among the progeny (minimum coancestry contributions), is the most widely proposed criterion to maintain genetic diversity (Toro and Pérez-Enciso, 1990;Ballou and Lacy, 1995;Fernándezet al., 2003;Meuwissen, 2007). This method has been shown to minimise the variance of the long-term contributions from ancestors to descendants and, therefore, to maximise effective population size (Caballero and Toro, 2000,2002).

The above methods are all designed to reduce the variation in family sizes, the term inEquation (1) and its corresponding components when the numbers of males and females are different (Equation (2)). It is also possible to increase the effective population size by decreasing the Mendelian segregation variance, which is represented by the constant term ‘2' inEquation (1). This latter can be achieved by the use of MAS to minimise the variation in contribution between the paternally and maternally derived genes at a locus (Wang and Hill, 2000). Thus, for example, for equal numbers of males and females and equalisation of individual contributions,Ne can be expressed as

inEquation (1) and its corresponding components when the numbers of males and females are different (Equation (2)). It is also possible to increase the effective population size by decreasing the Mendelian segregation variance, which is represented by the constant term ‘2' inEquation (1). This latter can be achieved by the use of MAS to minimise the variation in contribution between the paternally and maternally derived genes at a locus (Wang and Hill, 2000). Thus, for example, for equal numbers of males and females and equalisation of individual contributions,Ne can be expressed as

|

wherePm,mf (Pf,mf) is the probability that the two genes coming from the male (female) parent and contributing to their male and female progeny are copies of the same gene. By MAS, it is possible to reduce these probabilities below the value of 0.5 expected under no control of Mendelian segregation, depending on the amount of marker information, the genome size and the number of marker-genotyped offspring per family, achieving values ofNe>2N. MAS can also be used in a more general framework of different numbers of males and females to minimise global genetic drift and inbreeding (Wang, 2001a).

An alternative and complementary method is to use reproductive technologies for meiosis manipulation, such asin vitro culture of premeiotic germ cells and microinjection of primary spermatocytes into oocytes. By using more than one gamete from a single meiosis, variation from Mendelian segregation can be partially or completely removed (Santiago and Caballero, 2001). Thus, for example, if equalisation of family sizes is carried out and the gametes from both male and female parents are managed to come from the same meiosis in each case, the resulting effective size becomes 3N, rather than the typical 2N.

The control of the increase in inbreeding and genetic drift in conservation programmes is mainly addressed by reducing the variances of genetic contributions between paternally and maternally derived genes within and between individuals by equalising family sizes and minimising Mendelian segregation variance, as discussed above. A minor contribution to this control can also be achieved by the avoidance of inbred matings and other types of non-random mating. The simple avoidance of sib mating has a very minor effect (Wang, 1997d) and methods such as the maximum avoidance of inbreeding proposed byWright (1921) have a higher, although still relatively low, impact. These can be carried out after the design of parental contributions has been implemented (Caballeroet al., 1996a;Meuwissen, 2007). Alternatively, avoidance of inbreeding and optimal parental contributions can be realised in a single step (Fernándezet al., 2004) by the so-called mate selection method. Systems of mating involving circular (half-sib mating) (Kimura and Crow, 1963b;Theodorou and Couvet, 2010) or rotational schemes (Nomura and Yonezawa, 1996) generally reduce the ultimate rate of inbreeding but at the cost of higher initial rates (Robertson, 1964), so that their use in conservation is not recommended because of the high risk of extinction from inbreeding depression. Some methods are of particular application in selection programmes, such as the compensatory mating proposed bySantiago and Caballero (1995), where individuals from large families are mated to individuals from small ones. This produces negative correlations between the drift caused by selection and the drift caused by sampling, partly counteracting the cumulative effect of selection represented by the termQ inEquation (12). This system of mating in combination with maximum avoidance of inbreeding allows for a substantial reduction of inbreeding (Caballeroet al., 1996a).

A conservation strategy of high relevance in fisheries is supportive breeding (Hareet al., 2011), where a population is typically divided into a captive and a wild group and the offspring of the captive group are released into the wild habitat to mix with the offspring from the wild group. Because the captive group (permanent or transitional) is bred to produce a lot of offspring that are released into the wild group at each generation, the variance in family size is greatly elevated artificially and thus theNe of the entire population is reduced. Ironically, the more successful the supportive programme is in augmenting the wild population, the greater the reduction inNe and the greater the loss of genetic diversity in the total population (supportive+wild). This paradox is overcome only when successful supportive breeding in augmenting the wild population is carried out over a long period of time such that the excessive drift and inbreeding in the initial generations of supportive breeding is compensated for by weaker drift and inbreeding in later generations because of the increase in census size.Ryman and Laikre (1991),Rymanet al. (1995) andWang and Ryman (2001) have provided approximations for the inbreeding and variance effective sizes, respectively, which can be different in this case, with one generation of supportive breeding.Nomura (1998a) obtained an expression ofNe from the change in coancestry, which agrees with the variance effective size, as expected. In this scenario, with various census sizes and a mixture of groups, predictions depend, however, on the generations considered (seeRymanet al., 1999).

For endangered species in the wild, estimating the effective population size and monitoring its changes over time is important in understanding the genetic health, evaluating the risk of inbreeding and inbreeding depression and thus the risk of extinction, assessing the effectiveness of the genetic managements (for example, human-aided migration/relocation, habitat protection or modification) and projecting the future demographic trajectories of the populations. Simulations (Tallmonet al., 2010) showed that monitoring the effective size is most often a more robust means of identifying stable and declining populations than monitoring census size. If a population is detected to have a small or decliningNe, the managers of the populations should be alerted to investigate the causes and to take effective measures for reversing the course. Using noninvasive sampling (for example, from faeces, feathers, hair and so on), genetic marker data can be obtained from a population even without observing (disturbing) the animals. The data can then be analysed normally, except for accounting for the possibility of genotyping errors and allowing for a high frequency of missing data (for example,Wang, 2004), in estimatingNe. For example, in a long-term monitoring project,Kamathet al. (2015) sampled and genotyped (at 20 microsatellite loci) 729 Yellowstone grizzly bears (Ursus arctos) born in the period 1962–2010 from an isolated and well-studied population in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. They used the data to study the population demographic trajectories, estimating the changes inNe and generation interval, over this time period.

Methods for estimating the effective population size from genetic data

Given the concepts of effective size, different approaches can be used to predict the effective size of a population from its demographic parameters, such as census size and variance of reproductive success. In parallel, different methodologies can also be developed to estimate the realized effective size of a population from its genetic properties revealed by genetic markers, such as temporal changes in allele frequency and linkage disequilibrium (LD).

Quite a few methods (Schwartzet al., 1999;Beaumont, 2003a;Wang, 2005;Palstra and Ruzzante, 2008;Luikartet al., 2010;Gilbert and Whitlock, 2015) have been developed and applied to estimatingNe in widely different spatial and timescales, from ancient, past to current (parental) population sizes. Herein we focus on the effective size of the current generation or just a few generations in the past, as this timescale is the most relevant for conservation genetics (Luikartet al., 2010) and plant and animal breeding and is most likely to yield accurate estimates in current practices.

Heterozygosity excess

Compared with an infinitely large population at Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, a population generated from a number ofNm male parents and a number ofNf female parents is expected to show a deficit of homozygotes and an excess of heterozygotes at a neutral locus whenNm,Nf or both are small. This is because male and female parents are expected to have different allele frequencies owing to drift. The smaller the value ofNm orNf, the greater the difference between paternal and maternal allele frequencies and thus the greater the excess in heterozygosity of the offspring population. There is a simple functional relationship between theNe of the parental population and the amount of heterozygosity excess in the offspring population (for example,Robertson, 1965;Wang, 1996a). For a Wright–Fisher ideal population except for separate sexes withNm male andNf female parents, the heterozygosity excess is expected to be

|

whereNe=4NmNf/(Nm+Nf) is the effective size of the parental population given byEquation (4). The value ofD is negative, indicating an excess of heterozygosity and a corresponding deficit of homozygosity. For a non-ideal population with arbitrary distributions of family sizes,Equation (23) is still valid whenNm andNf are replaced byNem andNef, respectively, the effective numbers of male and female breeders.

Equation (23) suggests that measuring the heterozygosity excess,D, at a number of marker loci in a population yields an estimate of the parental population effective size.Pudovkinet al. (1996) proposed such aNe estimator by accounting for the sampling effect,

|

where the observed heterozygosity excess is estimated by ,

, is the expected heterozygosity from the observed gene frequency

is the expected heterozygosity from the observed gene frequency and

and is the observed heterozygosity.

is the observed heterozygosity. is calculated for each allele in a multiallelic locus and for each locus, and the average value is used inEquation (24) (Luikart and Cornuet, 1999). The accuracy of the estimator was evaluated byPudovkinet al. (1996) using simulations and was applied to a few empirical data sets (Luikart and Cornuet, 1999). The method is simple and is implemented in several computer programs (for example,Zhdanova and Pudovkin, 2008;Jones and Wang, 2010;Doet al., 2014). However, the method has a low precision and accuracy, frequently providing infinitely large estimates ofNe for small populations. The estimator is also highly sensitive to non-random mating (for example, population subdivision, close relative mating), which also causes deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. Its poor performance renders it useless in applications to empirical data set analysis, except when the actual population size is very small and marker information is ample.

is calculated for each allele in a multiallelic locus and for each locus, and the average value is used inEquation (24) (Luikart and Cornuet, 1999). The accuracy of the estimator was evaluated byPudovkinet al. (1996) using simulations and was applied to a few empirical data sets (Luikart and Cornuet, 1999). The method is simple and is implemented in several computer programs (for example,Zhdanova and Pudovkin, 2008;Jones and Wang, 2010;Doet al., 2014). However, the method has a low precision and accuracy, frequently providing infinitely large estimates ofNe for small populations. The estimator is also highly sensitive to non-random mating (for example, population subdivision, close relative mating), which also causes deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. Its poor performance renders it useless in applications to empirical data set analysis, except when the actual population size is very small and marker information is ample.

Linkage disequilibrium

In a large unselected random mating population, alleles are independent within and between loci, producing Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium and linkage equilibrium. In a finite population, however, random genetic drift leads to associations between alleles at a locus and between alleles of different loci. The former results in heterozygosity excess, and the latter leads to gametic LD. In addition to drift, LD can also be induced by factors such as migration and direct or indirect (for example, hitchhiking) selection (Hedricket al., 1978). For neutral loci unlinked with selected loci in an isolated population under random mating, LD would come exclusively from genetic drift and can be used to estimateNe (Hill, 1981).

An LD estimator ofNe for a random mating population at equilibrium is based on the formulation (Hill, 1981),

|

wherec is the recombination rate (c=1/2 for unlinked loci),r is the correlation of allele frequencies between two loci owing to LD andn is the sample size (number of sampled individuals). In an equilibrium population, allele frequencies at two neutral loci are expected to be uncorrelated (that is,E[r]=0), such that the expectation of squaredr,E[r2], is equal to the variance ofr,V[r].Equation (25) shows thatV[r] is composed of two distinctive parts. The first comes from genetic drift, determined byNe and linkagec. The second comes from sampling, determined by sample sizen. Using the genotypes at a number of loci ofn sampled individuals, we can estimateV[r], which can then be inserted inEquation (25) to obtain an estimate ofNe if the recombination fractionc between loci is known. Note that a slightly different expression for the populationV[r] (that is, the first part on the right-hand side ofEquation 25) was derived bySved (1971) from an identity by descent approach. For a dioecious population with monogamy, the right side ofEquation (25) should be increased byc/(2Nec(2−c)) (Weir and Hill, 1980).

Hill (1981) also derived the formula for the sampling variance of the estimator such that uncertainties of theNe estimates can also be evaluated. For the case of no linkage,Waples (2006) showed by simulations that the LD estimator can seriously underestimateNe when sample size is small. He derived empirical equations to correct for the bias caused by small sample sizes and showed by simulations that the accuracy of the modified estimator is comparable to the temporal method described in the next section. To facilitate the applications of the LD estimator,Waples and Do (2008) published a computer program, LDNE, and further evaluated its performance in comparison with the temporal method, using simulated data (Waples and Do, 2010). They concluded that, under similar conditions in terms of marker information and the actual population size, LD estimator can yieldNe estimates that have equivalent or better qualities than the temporal estimators, except when the sampling interval of the temporal method is long.

The LD estimator is simple to calculate and requires just a single sample of multilocus genotypes instead of two or more samples, as is with the temporal method (see below). It is especially suitable for species with a long generation interval where obtaining two samples separated by a couple of generations means many years and for genetic monitoring (Schwartzet al., 2007) to track population trajectories on a yearly basis. As a result, the LD estimator has gained popularity in recent years (Palstra and Ruzzante, 2008;Luikartet al., 2010). However, some assumptions inherent to the LD estimators are often violated in real populations and as a result may lead to biasedNe estimates. For example, it is assumed that LD is produced solely from the finite population size, and other confounding factors, such as non-random mating and population structure, are absent. Any departure from random mating (for example, an excess or deficit of close relatives mating including selfing) will affect LD and thus LD-based estimates ofNe.Wapleset al. (2014) evaluated the effect of age structure on LD estimators and found that LD calculated from mixed-age adult samples is overestimated and thusNe is underestimated in all of the 21 simulated species with different life tables. Similarly, the LD in a subpopulation is reduced by a constant and high rate of immigration and elevated by a low rate of immigration, compared with that of an isolated population of the sameNe. Therefore, as observed byWaples and England (2011) in their simulation study, LD calculated from a sample from a subpopulation leads to an overestimate or an underestimate of localNe when immigration rate is high or low, respectively. In the former case, the estimated localNe converges to the globalNe of the entire population (Waples and England, 2011).

LD is highly dependent on the recombination rate between loci (Hill, 1981). Pairs of closer linked loci have higher LD and thus provide better information aboutNe (suitably defined in timescale) if the linkage information among loci is known. AlthoughHill (1981) derived his LD estimator ofNe allowing for an arbitrary level of linkage and he advocated the use of linked markers, most often unlinked markers are used in practice because either truly unlinked markers are used or potentially linked markers are used but their linkage relationship is unknown. LD of markers of different recombination rates sheds light on the effective size of the population in different time periods in the past (Wang, 2005). Quite a few methods (Hayeset al., 2003;Barbatoet al., 2015;Mezzavilla and Ghirotto, 2015;Sauraet al., 2015) have been developed to exploit the LD information from many densely spaced markers on a chromosome segment in inferring theNe at different time points in the past.

Temporal changes in allele frequency

For an infinitely large population under Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, both allele frequencies and genotype frequencies remain unchanged over time. In reality, these frequencies never stay constant and change systematically owing to the forces of mutation, selection and migration, stochastically due to the random force of genetic drift, or both. In the absence of the action of all of the systematic forces in a population, any observed allele frequency change must come solely from genetic drift and can thus be used to infer the rate of drift or theNe of the population. Based on this logic,Krimbas and Tsakas (1971) proposed to measure allele frequency changes at a number of marker loci between two temporally separated samples of individuals and thereby to estimate theNe of the population during the sampling interval. This so-called ‘temporal method' was subsequently developed by many others in both (allele frequency) moment (for example,Nei and Tajima, 1981;Pollak, 1983;Waples, 1989) and likelihood (for example,Williamson and Slatkin, 1999;Andersonet al., 2000;Wang, 2001b;Berthieret al., 2002;Beaumont, 2003b;Lavalet al., 2003) approaches.

Moment estimators calculate a standardised variance in the temporal changes of allele frequency,F, from marker genotypes in two temporally spaced samples.F is essentially similar to Wright'sFST, the differences being thatF measures the temporal differentiation for the same population and it also includes sampling effect. There are a fewF estimators (for example,Nei and Tajima, 1981;Pollak, 1983) available, the one being widely applied was derived byNei and Tajima (1981). This estimator is calculated by

|

for a locus withk alleles, wherexi andyi are the observed frequencies of allelei in the first and second samples, respectively. For multiple loci, is obtained by averaging single-locus estimates. The expectation of

is obtained by averaging single-locus estimates. The expectation of depends on the sampling schemes (sampling with or without replacements) and is a function ofNe and sample sizes to account for genetic drift and sampling effects. Solving the expectation equation of

depends on the sampling schemes (sampling with or without replacements) and is a function ofNe and sample sizes to account for genetic drift and sampling effects. Solving the expectation equation of forNe yields the temporal estimate of the (harmonic) meanNe during the sampling period (Nei and Tajima, 1981;Waples, 1989).

forNe yields the temporal estimate of the (harmonic) meanNe during the sampling period (Nei and Tajima, 1981;Waples, 1989).

Moment estimators rely on the summary statistic,F, which is simple to calculate. However, they do not use the full allele frequency information and are thus less accurate than the probabilistic methods. The latter, likelihood or Bayesian, are much more complicated in statistical modelling and in computation. In general, temporal methods provide good estimates ofNe when it is not large, sampling interval is not too short (for example, one generation) and the assumptions of the methods are satisfied, using a typical set of 10–20 microsatellites. Likelihood methods generally have higher accuracy and precision than moment methods, especially for markers with rare alleles, as verified by several extensive simulations (for example,Wang, 2001b;Berthieret al., 2002;Tallmonet al., 2004). They are, however, much more computationally demanding than moment methods, which complete an analysis almost instantly. Recently, the computational efficiency of likelihood methods has been improved substantially byHui and Burt (2015), using a hidden Markov algorithm and applying continuous approximations to allele frequencies and transition probabilities. The new method can deal withNe values as high as several millions and is implemented in an R package called NB.

A constraint on the applications of temporal approaches is the requirement of at least two samples taken at one or preferably more generations apart. The longer this sampling interval,t, is, the stronger the drift signal will be in the temporal data and the more accurate theNe estimate will become. The extent of drift is proportional tot and is inversely proportional toNe. For the same population and the same sampling intensity (in terms of the number of markers, number of samples and number of individuals per sample), increasing the sampling intervalt could improve the accuracy of the temporal methods tremendously, as has been repeatedly verified by simulations (for example,Nei and Tajima, 1981). Moment estimators have especially low accuracy whent is small (say,t<3) because of the weak drift signal and also because of the approximations made to the estimators. In practice, it is unfortunately difficult or unrealistic to increaset, especially for long-lived species having a long generation interval.

Compared with otherNe estimating approaches, the temporal approach makes fewer assumptions and is more robust to some complications (realities) in real populations. For example, the approach is robust to population structure. It applies to a single unsubdivided population under non-random mating (including selfing) and to a subdivided population when sampling is representative and the aim is to estimate theNe of the entire subdivided population rather than that of a single subpopulation. It is also robust to age structure in a population with overlapping generations, so long as the sampling intervalt is large (for example,Nei and Tajima, 1981). Whent is small, however,Waples and Yokota (2007) showed by simulations that typical sampling regimes (sampling only newborns, only adults and all age classes in proportions) result in biasedNe estimates.Jorde and Ryman (1995) developed a moment estimator ofNe applicable to populations with overlapping generations. They derived an age–structure correction factor, which, when applied to the standard moment estimator for populations with discrete generations, leads to unbiasedNe estimates for populations with overlapping generations. Unfortunately, however, the correction factor is a function of numerous age-specific survival rates and age-specific reproduction rates of the focal population. These rates are usually unknown. In fact, once all these rates are known for a population, theNe of the population can be calculated from standardNe prediction equations (for example,Felsenstein, 1971;Hill, 1972,1979) without the need of genetic data. A method to calculate theNe of a population with overlapping generations from its demographic parameters has been implemented in an R-package Neff (Grimmet al., 2016).

The standard temporal approach for a single unsubdivided population was also extended to estimate theNe of a subpopulation that is connected to other subpopulations by gene flow (Wang and Whitlock, 2003). Although both drift and immigration change allele frequencies of a subpopulation, the detailed patterns of the changes are different between drift and immigration. Using temporal samples from a focal subpopulation and a sample from a large source population (the island–mainland model) or from two focal subpopulations (the island–island model), a moment estimator and a likelihood estimator can yield joint estimates ofNe and migration rates,m. Simulations showed (Wang and Whitlock, 2003) that both moment and likelihood estimators gave reasonably good estimates ofNe andm under typical sampling intensities. However, no estimators are available for the more general case of multiple (n>2) subpopulations. Part of the difficulty is with the number,n2, of parameters to be jointly estimated, includingn effective sizes andn(n−1) migration rates. More work is badly needed in this direction as spatial and temporal genotype data are becoming easy to collect thanks to the rapid developments in molecular technologies.

One of the assumptions in the temporal approach is the absence of selection so that any change in allele frequency comes solely from drift and thus indicates the effective size of the population. For most marker loci, the assumption is valid, especially for a small population over a short sampling interval of just a few generations. However, over a long period, some loci could be affected by adaptive selection or purging selection and their allele frequencies could change faster or slower than those of neutral loci unaffected by selection. Allele frequencies at neutral loci could also evolve faster or slower because of LD with those under selection. The temporal methods have been extended to estimateNe of a population and the selection coefficient,s, of a locus from time series data of allele frequencies (for example,Bollbacket al., 2008;Mathieson and McVean, 2013;Follet al., 2015). These methods are usually Bayesian, based on hidden Markov models to explain the observed allele frequency changes owing to drift and selection. How well these methods perform has yet to be checked, perhaps by a simulation study.

Relatedness and relationship

The pattern of genetic relatedness or relationship between individuals in a population has a direct functional relationship with the inbreeding effective size of the population (Wang, 2009). Two individuals taken at random from a population with a smallerNe will have a higher probability of sharing the same father, mother or both. More generally, the mean and variance in pairwise relatedness within a generation are expected to increase with decreasingNe. Based on this logic,Nomura (2008) proposed a method to use the increase in average coancestry between two consecutive generations to estimateNe. He showed by simulations that his coancestry method is more biased but more precise than the heterozygosity excess method. The overall accuracy (measured by mean squared errors) of the two methods is similar. A major problem which causes the bias of the method, as recognised byNomura (2008), is that some non-sib pairs must be selected from a sample of individuals to act as reference in estimating the mean coancestry. The selection of non-sib pairs is difficult and somewhat subjective, because it is now well known that classifying dyads into even well-separated relationship categories, for example, full sibs, half sibs, parent offspring and unrelated, from pairwise relatedness estimates is highly error prone (for example,Blouinet al., 1996). Although many marker-based pairwise relatedness estimators are unbiased, they have high sampling errors with no exceptions (Wang, 2014).

A more robust and powerful method is to estimate the frequencies of half-sib (sharing a single parent) and full-sib (sharing both parents) dyads,QHS andQFS, in a sample taken at random from a single cohort of a population (Wang, 2009;Waples and Waples, 2011).Wang (2009) derived a formula ofNe in terms of half- and full-sib frequencies using both an inbreeding and a drift approach,

|

The equation has the parameterα as inEquation (5), so that theNe for a population under non-random mating (for example, partial selfing) can be estimated. WhileQHS andQFS can be estimated from a sibship assignment analysis of the multilocus genotypes (Wang and Santure, 2009;Jones and Wang, 2010),α can be estimated from the same data with anFST-like approach (Wang, 2009). Alternatively,α can be assumed to be 0 for an outbred population when marker genotype frequencies do not deviate significantly from those expected under Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. The difficulty comes from the estimation of the numbers of breeding males,Nm, and females,Nf, because sibship analysis generally makes no distinctions between paternal and maternal sibships from autosomal marker data, except in some specific situations (Wang, 2009). However, as detailed inWang (2009), the bias brought about by the last term ofEquation (27), , is usually negligible becauseα is usually small and the estimate of

, is usually negligible becauseα is usually small and the estimate of by a sibship analysis is also not too far from its true value.

by a sibship analysis is also not too far from its true value.

There are several advantages of this sibship approach compared with other single-sample approaches toNe estimation. First, sibship can be inferred more accurately than other quantities such as relatedness, which leads to more accurate estimates ofNe. Second, the approach applies to non-random mating populations, as an inbreeding coefficientα (Equation (5); equivalent to Wright'sFIS) can be calculated from the genotype data and incorporated into theNe estimate. Similarly, the approach is also robust to population subdivision, as discussed byWang (2009). Third, it applies to diploid species, haplodiploid species, dioecious as well as monoecious species with selfing. Fourth, a great advantage is that it provides not only an estimate of the summary parameterNe but also some information about the numbers of male and female parents and variance in family sizes through the sibship assignment analysis. This detailed information is especially valuable for conservation management, as a lowNe owing to high variance in family size or a low number of parents would imply different management strategies. Simulations verified that the approach is much more accurate than the heterozygosity excess method and is similar in accuracy to the temporal methods (Wang, 2009). However, it is unclear how its accuracy compares with that of the LD method. More work is needed to clarify this issue.

The above sibship frequency approach assumes a population with discrete generations. For a population with overlapping generations, the estimate provided by the sibship frequencies in a sample of single-cohort individuals is the effective number of breeders,Nb. This parameter summarises the effects of variation in reproductive success between age classes, between sexes and between individuals within an age–sex class on genetic drift in a single breeding season, instead of in a lifetime. It is less useful thanNe, and no population genetic equations are in terms ofNb. However, in the absence of an estimate ofNe,Nb provides some information about the risks of inbreeding and loss of genetic variation in conservation populations (for example,Waples and Antao, 2014;Whiteleyet al., 2015). For the case of overlapping generations,Wanget al. (2010) proposed a parentage assignment method to estimate theNe and generation interval from the sex, age and multilocus genotype information of a single sample of individuals taken at random from a population. Essentially, the method estimates the life table by parentage assignments, and bothNe and generation interval are then calculated from the life table. Simulations showed that the method yields unbiased and reasonably accurate estimates ofNe under realistic sampling and genotyping effort. Application of the method to empirical data yields sensibleNe estimates that are supported by other sources of information from the population (Kamathet al., 2015).

Multiple sources of drift/inbreeding information

The above approaches toNe estimation use a single source of information, such as heterozygote excess, LD, temporal allele frequency changes and sibship/parentage frequencies. Each piece of information reflects a facet of the stochastic process (genetic drift or inbreeding) and combining multiple pieces of information may potentially allow for a better delineation of the process and thus yield a more accurate estimate ofNe.Tallmonet al. (2008) proposed to use approximate Bayesian computation (ABC) to estimateNe from a sample of microsatellite genotypes. Their method, implemented in a computer program ONESAMP, calculates and uses eight summary statistics that are known to have functional relationships withNe from population genetic theory or simulations. These statistics include, among others, the number of alleles per locus, expected heterozygosity, LD, Wright'sFIS and the mean and variance of multilocus homozygosity. In essence, the ABC approach simulates populations of differentNe and tries to find theNe value that yields the same or similar summary statistics to those calculated from the real data.Tallmonet al. (2008) demonstrated this ABC approach by analysing an introduced increasing population of ibexCapra ibex.

It is arguable that the ABC approach uses more information than other approaches. On the one hand, it uses multiple sources of information such as heterozygosity, number of alleles and LD. However, on the other hand, for each source of information, it uses a summary statistic rather than the full information that is used by the probability methods (likelihood or Bayesian). Furthermore, it is unclear how these different summary statistics should be optimally weighted, given that these statistics are, apparently, highly correlated and may reflect the inbreeding and drift processes of different timescales. For a population changing in size, these different summary statistics are relevant forNe in different timescales. For example,FIS (similar to heterozygosity excess) is pertinent to the parentalNe, and LD implicatesNe in the past few or more generations (depending on the linkage of the markers), while the number of alleles can be determined by the ancientNe many generations (in the order ofNe or 1/u, whichever is smaller, whereu is mutation rate) ago. So far, an extensive simulation study to compare the accuracy of ABC and other approaches is lacking but is urgently needed.

Discussion

Since the seminal work ofWright (1931,1933), great progress has been made on the pivotal population genetic parameter,Ne, in its concepts (for example, inbreeding, variance, eigenvalue effective sizes and so on), its predictions for various species under different mating systems and population structures and its estimation methodologies using various marker information. In parallel, estimates ofNe, from both demographic and genetic data, have been made for many populations in the past 30 years, thanks to the rapid developments in both molecular technologies and statistical and computational methodologies.

Much work has been carried out to predict the effect of selection onNe. However, developing useful predictive models on the effect of selection acting on an inherited trait remains difficult. The reason is that the impact of linked genes propagates over a number of generations, resulting in a long-term effect that is difficult to combine in a simple equation with parameters referred to only one generation time. Coalescence theory runs into similar difficulties in predictingNe, because the probabilities of coalescence for consecutive generations are not independent under selection on an inherited trait. In addition to the variation ofNe across generations, there is also variation over the genome. It is nowadays quite clear that there is a significant heterogeneity in levels and patterns of genetic variation across the genome caused by selection (Charlesworth, 2009;Gossmannet al., 2011), which complicates the inferences ofNe.

Another important remaining problem about selection is the inter-relationship betweenNe and genetic variation. Most equations ofNe are linear functions of the census sizeN where genetic variation of the selected trait is an independent variable. However, genetic variation itself depends onNe. Ignoring this fact is irrelevant for some purposes but is troublesome in some models of closely linked loci. This reciprocal dependence is on the basis of the Hill–Robertson effect (Hill and Robertson, 1966) and Mullerś ratchet (Haigh, 1978), both being different aspects of the same issue, an additional reduction of genetic variance owing to genetic drift induced by selection.

Demographic estimation ofNe can be made by application of the predictive equations reviewed here when information on census sizes, variances of progeny numbers, type of mating system and other demographic data are available. The lack of these data and the increasing availability of genetic markers make the estimation ofNe through genetic data to be, however, the leading procedure. Most factors affecting the populations in real situations imply a reduction of the effective size relative to the census size. In fact, the observed ratioNe/N has been found to be about 10–20% (Frankham, 1995;Palstra and Fraser, 2012) on average in meta-analyses across many species and populations. Overall, these figures are in agreement with theoretical expectations obtained from some of the predictive equations presented in this review when fluctuations in population size are considered (Vucetichet al., 1997). However, this averageNe/N ratio may be an overestimate, as marine species are under-represented in these meta-analyses and can have extremely lowNe/N ratios.