Role of the Primate Orbitofrontal Cortex in Mediating Anxious Temperament

Ned H Kalin

Steven E Shelton

Richard J Davidson

Address reprint requests to Ned H. Kalin, Wisconsin Psychiatric Institute and Clinics, University of Wisconsin-Medical School, 6001 Research Park Boulevard, Madison, WI, 53719-1176

Issue date 2007 Nov 15.

Abstract

Background

Excessive behavioral inhibition during childhood marks anxious temperament and is a risk factor for the development of anxiety and affective disorders. Studies in nonhuman primates can provide important information related to the expression of this risk factor, since threat-induced freezing in rhesus monkeys is a trait-like characteristic analogous to human behavioral inhibition.

The orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and amygdala are part of a circuit involved in the processing of emotions and associated physiological responses. Earlier work demonstrated involvement of the primate central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA) in mediating anxious temperament. This study assessed the role of the primate OFC in mediating anxious temperament and its involvement in fear responses.

Methods

Twelve adolescent rhesus monkeys were studied (six lesion and six controls). Lesions were targeted at regions of the OFC that are most interconnected with the amygdala. Behavior and physiological parameters were assessed before and after the lesions.

Results

The OFC lesions significantly decreased threat-induced freezing and marginally decreased fearful responses to a snake. The lesions also resulted in a leftward shift in frontal brain electrical activity consistent with a reduction in anxiety. The lesions did not significantly decrease hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) activity or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) concentrations of corticotropin releasing factor (CRF).

Conclusions

These findings demonstrate a role for the OFC in mediating anxious temperament and fear-related responses in adolescent primates. Because of the similarities between rhesus monkey threat-induced freezing and childhood behavioral inhibition, these findings are relevant to understanding mechanisms underlying anxious temperament in humans.

Introduction

Children with extreme behavioral inhibition are at risk to develop social anxiety disorder and depression [1–5]. We demonstrated that rhesus monkeys provide an excellent model to study mechanisms relevant to understanding human behavioral inhibition and anxious temperament [5,6] since these species share similarities in the expression of anxiety [5,6] and in the brain structures that mediate emotion [7,8]. Using rhesus monkeys, we have focused our efforts on understanding the physiological concomitants and neural mechanisms underlying individual differences in the expression of threat-induced freezing, which has trait-like characteristics and is analogous to human behavioral inhibition [5,6]. Our earlier studies demonstrated that a propensity to engage in increased threat-induced freezing is associated with increased basal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) activity, increased cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) concentrations of the anxiogenic peptide, corticotropin releasing factor (CRF), and asymmetric right frontal brain electrical activity [9–11]. Many of these physiological parameters have also been associated with individual differences in childhood behavioral inhibition, although the studies are not always consistent [3,12–14].

Human functional imaging studies have implicated the amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) as components of the neural circuitry involved in the adaptive processing of emotion and in psychopathology [15,16]. More specifically, increased amygdala reactivity occurs in adults with a childhood history of extreme behavioral inhibition [17]. We demonstrated, in monkeys, that lesions of the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA) decreased threat-induced freezing, snake fear, HPA activity and CSF CRF concentrations [18]. This suggested a mechanistic role for the CeA in mediating acute fear responses, human behavioral inhibition, and anxious temperament.

The OFC is of interest in relation to behavioral inhibition and anxious temperament because of its role in mediating longer-term responses associated with emotion-related goal-directed behavior [19–23]. Furthermore, the OFC is bidirectionally linked to the amygdala and these connections have been implicated in emotion regulation processes [5,24,25]. The medial regions of the OFC (Areas 13 and 14) receive the densest amygdala projections [7,26], whereas Areas 11 and the caudal region of Area 12 receive minimal to moderate amygdala [7,27,28]. These projections originate from the lateral, basal, and accessory basal nuclei of the amygdala [8,27,28]. In general, the OFC regions that receive amygdala projections reciprocate with projections back to the amygdala [8,26].

Therefore, to explore the role of the OFC in mediating behavioral inhibition, anxious temperament, and acute fear, we examined the effects of lesions of OFC regions that are linked to the amygdala (Areas 11, 12(orbital division), 13, and 14) on threat-induced freezing, snake fear, and the physiological parameters associated with anxious temperament. We used adolescent rhesus monkeys because in humans anxiety and affective psychopathology commonly emerges during adolescence and it appears that in monkeys the structural connections between the amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex are in place by adolescence (for review, see [9]). We hypothesized that the OFC lesions, similar to the effects of CeA lesions, would reduce the expression of the behavioral and physiological parameters associated with acute fear responses and anxious temperament.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Subjects

Twelve experimentally naïve adolescent colony-born rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) were the subjects. Animal housing and experimental procedures were in accordance with institutional guidelines. The animals were housed as pairs; each experimental animal lived with a control animal. At the beginning of the study, subjects were on average 34.4 months of age. Six randomly-selected males underwent surgery at an average age of 35.6 months. Six unoperated male controls were used for comparison since we previously demonstrated that the nonspecific effects of the surgery do not significantly affect the behavioral and physiological measures of interest [18].

Surgical procedure

Prior to surgery, atropine sulfate (.04 mg/kg IM) was given to depress salivary secretion, and dexamethasone (2 mg/kg) was given to reduce potential brain swelling. Animals were pre-anesthetized with ketamine HCl (10 mg/kg IM), fitted with an endotracheal tube, and maintained on isofluorane anesthesia. An experienced surgeon made an opening in the frontal bone posterior to the brow ridge to expose the frontal cortex. Both hemispheres were lesioned in a single procedure by lifting the brain to expose its ventral surface. Using microscopic guidance, electrocautery and suction were applied to the targeted brain area [20,30].

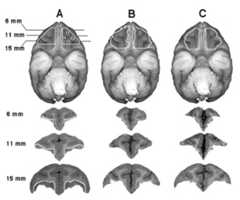

The intended lesion extended from the lateral edge of the ventral surface to the lateral olfactory tract. The rostral limit of the target was 5 mm posterior to front of the brain and the caudal limit was 4 mm anterior to the junction of the frontal and temporal lobes (regions of Areas 11, 12, 13, and 14) (Figure 1) [31].

Fig. 1.

The intended target for the OFC lesion is depicted in Column A: White lines define the intended lesion in the axial and coronal planes showing brain regions 11, 12, 13, and 14. Columns B and C define lesions in the axial plane by a white boundary and depict the range of the lesions from animals that have 65.7% (B) and 79.1% (C) of the targeted region. The lesions can be visualized in the coronal planes by comparing the remaining cortical gray matter with that of the control animal displayed in Column A.

Following surgery, dexamethasone 2 mg/kg IM was given twice daily and tapered by half each day for three days. Cefazolin (20 mg/kg IM) was administered twice daily for five days and ketofen (2.1 mg/kg IM) was given for analgesia every 8–12 hours for four days.

MRIs, Development of Lesion Target, and Lesion Verification

T1-weighted MRI scans were obtained using either a 1.5 or a 3.0 Tesla GE Signa MRI. Four of the six animals had pre- and post-surgical MRIs, and the remaining two animals had only post-surgical MRIs. For scanning, the monkeys were anesthetized with xylazine (0.5 mg/kg IM), with ketamine administered as needed (15 mg/kg IM). Post-surgical 3T MRIs were acquired an average of 35 days after the surgery by placing the monkeys in a specially designed plastic head holder within the scanner.

The intended lesion area was defined using coronal atlas brain slices beginning at the caudal boundary of Area 10 and extending 12 mm posteriorly (Figure 1) [31]. The brain atlas was also used to standardize each animal’s intended lesion to the pre-surgical MR images. To define the intended lesion for each of the animals, the coronal atlas pictures were matched to 12 pre-surgical MR images, except for one subject that only had nine images. For the two animals without a pre-surgical MRI, we used a MRI from an age- and sex-matched monkey. The post-surgical MRI was used to define each subject’s actual lesion, which was drawn onto the pre-surgical MRI along with the intended lesion. The extent of the lesion was expressed as a percentage of the intended lesion as calculated by counting the pixels within the animal’s actual lesion and dividing this by the number of pixels in the intended lesion for each coronal slice.

Threat-Related Anxiety

To assess defensive and anxiety related behaviors, all animals were tested before and after the lesions were made using two different paradigms, each with three different conditions [alone (A), no eye contact (NEC), and stare (ST)]. Control and experimental subjects were tested at the same time, and the mean time between the lesioning procedure and the first post-surgical behavioral test was 4.3 months. The first test was conducted using the classic human intruder paradigm (HIP), consisting of nine-minute periods of A, NEC, and ST. As part of a separate study, the second test used a modified HIP paradigm. In the classic HIP, during the A condition, animals were placed alone in a test cage for nine minutes. This condition predominantly elicits coo vocalizations and locomotion. This was followed by the NEC condition, in which a human entered the test room, stood motionless 2.5 m from the cage, and presented her profile to the monkey while avoiding eye contact. The NEC condition elicits freezing behavior. After NEC, the intruder left the test room for three minutes and returned for the ST condition, during which the intruder stared at the monkey with a neutral face 2.5 m from the test cage. The ST condition elicits defensive hostility and barking, an aggressive vocalization. The modified HIP consisted of 20 minutes of each of the three conditions (A, NEC, ST) on three different days. The classic and modified HIP paradigms were repeated for all subjects after the experimental animals were lesioned. Each animal’s behavior was encoded using a microprocessor-based syntactic behavioral scoring system by one experienced rater unaware of the treatment conditions (Table 1). For each behavior, the mean duration or frequency per minute was calculated. These data from both paradigms were combined for analysis to more accurately represent each animal’s behavior.

Table 1.

Definition of Behaviors

| Behavior | Definition |

|---|---|

| Coo | Vocalization made by rounding and pursing the lips with an increase then decrease in frequency and intensity. |

| Locomotion | Ambulation of one or more full steps at any speed. |

| Freezing | A period of at least three seconds characterized by tense body posture, without vocalizations and movement other than slow movements of the head. |

| Experimenter Hostility | Any hostile behavior directed toward the intruder, such as barking, head bobbing, and ear flapping. |

| Bark | Vocalization made by rapidly forcing air though the vocal chords from the abdomen, producing a short, rasping, low frequency sound. |

Assessing Snake Fear

Subjects were adapted to the Wisconsin General Testing Apparatus (WGTA) test cage, and their food preference was determined [32]. Subjects were taught to reach for their preferred rewards on top of clear plastic stimulus presentation box (57.2 × 22.1 × 6.5 cm). Subjects were presented with two of their most preferred foods randomly placed on the distant left and right corners of the clear plastic stimulus presentation box, requiring the subjects to reach over the stimulus for the food rewards. The box contained one of four stimuli: 1) Nothing: empty box; 2) Tape: roll of blue masking tape; 3) Rubber Snake: curled black rubber snake 120 cm long, 4) Snake: live northern pine snake (Pituophis melanoleucus) 170 cm long. Subjects were tested for one day, during which each stimulus was presented six times in a pseudo-random order. The real snake was never presented during the first five trials and no item from either the snake or the non-snake stimulus category was presented for more than three consecutive trials. Each monkey received the same order of stimuli. Each trial lasted 60 seconds regardless of the subject’s response, and the inter-trial interval was 45 seconds. Latency for the animal’s first reward retrieval in each trial was used for analysis.

Hormonal Sampling and Stress Exposure

Basal hormonal status and stress response were evaluated twice before and twice after surgery, at intervals of at least one week, by obtaining a blood sample within two minutes of capture immediately prior to and after 30 minutes of stress exposure. The stress consisted of 10 minutes of manual restraint followed by 20 minutes of confinement in a transport cage. All samples were collected between 0800 and 0930 hr. After the second blood sample was obtained following the stress exposure, ketamine HCl (15 mg/kg IM) was administered and a 3 ml CSF sample was obtained from the cisterna magna. Plasma was separated from blood by centrifugation at 4°C and frozen at −70°C. CSF samples were immediately frozen on dry ice and maintained at −70°C.

Cortisol, ACTH, and CRF Measurement

Cortisol was measured in plasma using an enzyme immunoassay kit (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Webster, TX) with an intraassay variability of 6.1% and an interassay variability of 6.3%. The detection limit of the assay was 0.125 ng. ACTH was measured using a radioimmunoassay kit from the Nichols Institute Diagnostics (San Clemente, CA). The intraassay variability was 2.2% and the interassay variability was 7.2%. The detection limit of the assay was 1.0 pg. CRF assays were performed by RIA using antiserum directed against the N - terminal portion of the intact peptide (IgG Corp., Nashville, TN). The detection limit was 0.89 pg. The intraassay and interassay CV% were 6.1% and 10.2%.

Frontal Brain Electrical Asymmetry Assessed with EEG

Silver-silver chloride biopotential electrodes were attached with conditioning cream to awake, manually-restrained animals. Electrodes were placed to the central (CZ) area, left and right frontal (F3, F4) areas, and left and right parietal (P3, P4) areas. Additional electrodes were placed on the left and right mastoids (A1, A2). All EEG electrodes and A2 were recorded with reference to A1, although EEG signals were analyzed after being re-referenced to a computed averaged mastoid value. EEG was acquired using the Vitaport 3 digital recorder from TEMEC Instruments B.V. (Kerkrade, The Netherlands).

Data were auto-scored (maximum value 350μV; maximum slope 2 μV/ms) to remove artifact. The duration of EEG data used was similar between groups (mean for controls = 452.34 sec, and for lesion subjects = 476.38 sec). Power spectra were estimated using Welch’s method [33] applied to 1.0 second linearly detrended and Hanning windowed epochs of artifact-free data with 0.5 seconds of overlap. Spectral power estimates (in μV2/Hz) for the five bands delta (1–4 Hz), (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–12 Hz) and beta (13–30 Hz) were averaged from the artifact-free data. The 4–8 Hz band was chosen because robust lateralized changes in this band occur in rhesus monkeys given diazepam [34]. Power density measurements were normalized by log transformation. The direction and magnitude of asymmetry were expressed as the log transformed power density of an electrode position on the right side of the head less the log transformed power density of the corresponding electrode on the left side of the head. Positive asymmetry scores reflect greater left-sided activation.

Statistical Analysis

Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) or paired t-tests were used to compare the groups. All post-hoc comparisons used t-tests. Non-normally distributed data were transformed using a square root transformation for frequency data and a log (X+1) transformation for duration data.

Results

Extent of OFC Lesions and Effects on Threat-Induced Anxiety and Snake Fear

Figure 1 displays the intended lesion target as well as coronal MRI slices, obtained after the lesioning procedure, from representative monkeys. The intent was to lesion cortical Areas 11, 13, the orbital region of Area 12, and the lateral part of the orbital region of Area 14. On average, 70.4% of the targeted area was destroyed ranging from 65.7% to 79.1% (Table 2). Areas outside the targeted region that received minimal damage included the orbital proisocortex (three animals), the orbital periallocortex (five animals), and the orbital portion of Area 25 (six animals) [31].

Table 2.

Percent Destruction of the Targeted Orbitofrontal Cortex

| Subjects | Left% | Right % | Mean % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 78.1 | 80.1 | 79.1 |

| 2 | 85.2 | 64.5 | 74.6 |

| 3 | 73.2 | 73.7 | 73.4 |

| 4 | 74.1 | 62.5 | 68.1 |

| 5 | 67.4 | 69.1 | 68.2 |

| 6 | 60.7 | 71.0 | 65.7 |

| Mean% | 69.0 | 71.9 | 70.4 |

During the A condition of the HIP, no significant effects of the lesions were observed on locomotion or cooing. Likewise, during ST, neither barking vocalizations nor hostile behaviors were significantly affected by the lesions. However, during NEC, the lesions significantly reduced the duration of threat-induced freezing. ANOVA revealed a significant group by test interaction (F = 5.373; d.f. = 1,10; p < .05) such that less freezing occurred in the lesioned subjects post-surgery when compared with their pre-surgical levels (p = .051). After surgery, the lesioned subjects also showed less freezing compared to the levels of freezing in the controls at either of the two testing times (p < .01) (Figure 2). The lesions did not significantly affect locomotion during NEC.

Fig. 2.

The OFC lesions resulted in a significant reduction in freezing duration during the NEC condition with a significant group (lesion vs. control) by test (pre-surgery vs. post-surgery) interaction (F = 5.371; d.f. = 1,10; p < .05). *Differs from control post at p < .009.

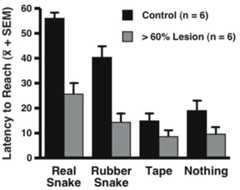

In the snake fear test, ANOVA revealed a main effect of object such that across control and lesioned animals, the greatest latencies to reach for the treat occurred in the presence of the real snake (F = 12.881; d.f. = 3,30; p < .0001). The latency to reach for the treat in the presence of the rubber snake was less than that for the real snake, but greater than that occurring in the presence of the roll of tape or when nothing was presented. In addition, there was a significant main effect of group and a near significant group by object interaction. The group effect was characterized by an overall decrease in the lesioned animals’ latencies to reach (F = 6.819; d.f. = 1,10; p < .03).Figure 3 displays the group by object interaction, demonstrating that the differences in the lesioned and control animals’ latencies to reach were greatest in response to the real and rubber snake (F = 2.560; d.f. = 3,30; p = .074).

Fig. 3.

A significant main effect of OFC lesions (F = 6.819; d.f. = 1,10; p < .03) and a trend towards a group by object interaction (F = 2.560; d.f. = 3,30; p = .074) was observed. The lesions resulted in reduced reach latency in response to all objects, with the greatest reductions occurring in response to the real and rubber snake stimuli.

Effects of Lesions on Frontal EEG Asymmetry and Stress-Related Hormones

The lesions significantly affected the monkeys’ patterns of frontal brain electrical activity as evidenced by a group by test interaction (F = 9.503; d.f. = 1,10; p < .02). After surgery, the OFC-lesioned animals demonstrated an increase in left compared to right frontal electrical activity. In comparison, the control animals remained unchanged across the two tests (Figure 4). A similar pattern of change was observed for parietal brain activity (F = 4.877, d.f. = 1,10; p = .052). The lesions were without significant effect on baseline or stress-induced increases in plasma concentrations of cortisol or ACTH and did not alter CSF CRF concentrations.

Fig. 4.

The OFC lesions resulted in greater relative left-sided brain electrical activity. The group (lesion vs. control) by test (pre-surgery vs. post-surgery) interaction was significant (F = 9.503; d.f. = 1,10; p < .02). *Differs from control post at p < .03.

Discussion

These findings from adolescent primates demonstrate involvement of the OFC in mediating threat-induced freezing, a behavior that is analogous to human behavioral inhibition and is a characteristic of trait-like anxiety. The lesions also affected the monkeys’ overall latencies to reach for a preferred treat in response to the presentation of fearful and non-fearful objects. The data suggest that this effect of the lesions was more prominent in relation to the snake, a fearful stimulus. The OFC lesions also significantly increased left frontal asymmetric brain electrical activity and were without effect on HPA activity and CSF CRF concentrations. The behavioral effects of the OFC lesions were similar to those reported for lesions of the CeA [18]. However, unlike the OFC lesions, the CeA lesions did not affect patterns of frontal brain electrical activity, but did decrease HPA activity and CSF CRF concentrations. Along with our earlier work, these findings suggest a role for the OFC and CeA in mediating human behavioral inhibition [1–5]. The findings also suggest a role of the OFC in modulating patterns of frontal brain electrical activity, which is of interest since asymmetric right frontal electrical activity is associated with anxious temperament [2,3,5,6,9]. Since rodent and human studies suggest a role for the ventromedial prefrontal cortex in inhibiting amygdala activity and in mediating extinction [25,36], it is important to note that our OFC lesions did not affect this region. Lesions of this area might be expected to have effects opposite to those of the OFC lesions.

It is of considerable interest that the OFC lesions reduced threat-induced freezing in adolescent monkeys since in humans, anxiety and affective psychopathology emerges during adolescence. Furthermore, our finding in adolescent monkeys is consistent with a recent study in brain-injured children and adolescents demonstrating that OFC damage decreased the likelihood of developing anxiety symptoms [35].

In our study, the effects of the OFC lesions on threat-induced freezing appeared to be selective since there were no significant effects of the lesions on locomotion or cooing occurring during the A, nor on barking or defensive hostility occurring during ST. A recent study using four OFC lesioned monkeys that were tested in a modification of the HIP failed to find an effect of OFC lesions on “defensive behaviors” elicited by the NEC condition [37]. The failure to find this effect could be because much less behavior was assessed (5 min compared to 29 min in our study) or that freezing behavior was not separately analyzed but was combined with other defensive behaviors. Furthermore, our within-subjects design increased the statistical power to detect effects. In addition, the Izquierdo et al. study differed from ours in that they did not lesion the orbital portion of Area 12. In contrast to early reports demonstrating that OFC-lesioned monkeys have altered aggressive behavior [34,38] we did not find an effect of the lesions on defensive hostility elicited by ST. More recently, OFC lesions were reported to increase “mild aggression” (frown, ears back, and yawn) but not “high aggression” (thrusts head or body forward, cage shake, threat face) occurring during 5 min of ST exposure [37]. Since our behavioral category “defensive hostility” incorporates both mild and high levels of aggression as defined by Izquierdo et al, the possibility exists that our behavioral rating of hostility was not sensitive enough to detect differences in this more subtle aggressive behavior.

The finding that the OFC lesions decreased snake fear is consistent with other studies [37,39]. While this finding was only marginally significant, it is likely that the amygdala and OFC work together to mediate snake fear as there are a number of primate studies demonstrating that total amygdala or CeA lesions reduce snake fear [18,32,37,40]. Furthermore, monkeys with combined unilateral amygdala and OFC lesions demonstrate a reduction in snake fear [41].

The effects of the OFC lesions on behavior were similar to those observed for CeA lesions [18], however the effects of the lesions differed on the assessed physiological parameters. In contrast to the CeA lesions, the OFC lesions did not significantly decrease HPA activity or CSF levels of the anxiogenic neuropeptide, CRF. The failure to detect a decrease in CSF CRF after the OFC lesions supports the possibility that the decrease in CSF CRF associated with the CeA lesions may result from lesioning CeA CRF-containing neurons [18]. The relation among the behavioral and physiological parameters associated with anxious temperament is complex. Increased HPA activity has been linked to anxious temperament as studies in extremely inhibited children have found increased cortisol concentrations [13]. We previously demonstrated that individual differences in monkeys’ freezing behavior positively correlate with plasma cortisol concentrations [11] and we also found that monkeys and children with extreme asymmetric right frontal brain electrical activity have increased plasma cortisol concentrations [9,42] and monkeys with right asymmetric frontal brain activity also have increased CSF CRF levels [10]. Furthermore, asymmetric right frontal brain electrical activity is associated with negative affect in humans and anxious temperament and increased anxiety-related behaviors in monkeys [9,10,14,43]. Therefore, it is of interest that the OFC lesions resulted in a shift in frontal brain electrical activity towards increased left asymmetry, but did not affect HPA activity or CSF CRF concentrations.

In the lesioned monkeys, the association between a decrease in anxiety and a leftward shift in frontal brain activity is consistent with an earlier finding demonstrating that the administration of the anti-anxiety agent, diazepam, results in a similar effect [44]. However, a reduction in anxiety is not always accompanied by a leftward shift in frontal brain electrical activity, as we previously found that CeA lesions decreased anxiety responses without affecting patterns of frontal brain electrical activity [18,32]. It may be that the regions of OFC lesioned in this study modulate prefrontal cortical connectivity in a way that is reflected in prefrontal electrical asymmetries. In contrast, lesions of the amygdala might not directly interfere with the prefrontal circuitry involved in modulating prefrontal electrical asymmetries. That CeA and OFC lesions affect threat-induced freezing along with some but not all of the physiological parameters associated with anxious temperament again underscores the complex relation among these brain regions with the behavioral and physiological aspects of this temperament.

In addition to behavioral inhibition, anxious temperament involves avoidant behaviors that are motivated by the habitual perception that the environment is threatening. A well-established function of the OFC is to modulate goal-directed behavior based on the assessment of future positive and negative consequences, and it has been hypothesized to be involved in emotion regulation [19–23]. It is therefore logical that the OFC would be involved in mediating anxious temperament and behavioral inhibition since they are enduring dispositions related to emotion regulation. Together with earlier work, these findings suggest that in primates the OFC and amygdala are components of the circuitry that mediate the expression of the behavioral and physiological responses associated with the anxious temperament. Bidirectional linkages between the amygdala and OFC provide the pathways to mediate their coordinated effects.

While numerous human functional imaging studies have reported alterations in OFC and amygdala activity in relation to human psychopathology [15,16], the conclusions from these studies are based on associations among behavior, emotion, and brain activity. By directly disrupting OFC function in primates, the current study supports the findings from the imaging studies by demonstrating a mechanistic role of these structures in the processing and regulation of anxiety. These findings have important implications for understanding the mechanisms underlying the risk of developing anxiety and affective disorders.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to H. Van Valkenberg, T. Johnson, E. Zao, K. Meyer, J. King, S. Mansavage, J. Droster, L. Greischar and the staff at the Harlow Center for Biological Psychology and the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center at the University of Wisconsin (RR000167) for their technical support, and Drs. Elisabeth Murray and Jocelyne Bachevalier for their neurosurgical advice. This work was supported by grants MH046729, MH052354, MH069315, The HealthEmotions Research Institute and Meriter Hospital.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures

The authors do not have any conflicts to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Biederman J, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Rosenbaum JF, Herot C, Friedman D, Snidman N, et al. Further evidence of association between behavioral inhibition and social anxiety in children. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1673–1679. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Newman DL, Silva PA. Behavioral observations at age 3 years predict adult psychiatric disorders. Longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:1033–1039. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830110071009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fox NA, Henderson HA, Marshall PJ, Nichols KE, Ghera MM. Behavioral inhibition: linking biology and behavior within a developmental framework. Annu Rev Psychol. 2005;56:235–262. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kagan J, Reznick JS, Snidman N. The Physiology and Psychology of Behavioral Inhibition in Children. Child Dev. 1987;58:1459–1473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalin NH, Shelton SE. Nonhuman primate models to study anxiety, emotion regulation, and psychopathology. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1008:189–200. doi: 10.1196/annals.1301.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalin NH, Shelton SE. Defensive Behaviors in Infant Rhesus Monkeys: Environmental Cues and Neurochemical Regulation. Science. 1989;243:1718–1721. doi: 10.1126/science.2564702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amaral DG, Price JL. Amygdalo-cortical projections in the monkey (Macaca fascicularis) J Comp Neurol. 1984;230:465–496. doi: 10.1002/cne.902300402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amaral DG, Price JL, Pitkanen A, Carmichael ST. Anatomical Organization of the Primate Amygdaloid Complex. The Amygdala: Neurobiological Aspects of Emotion, Memory, and Mental Dysfunction. 1992;1:1–66. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalin NH, Larson C, Shelton SE, Davidson RJ. Asymmetric frontal brain activity, cortisol, and behavior associated with fearful temperament in rhesus monkeys. Behav Neurosci. 1998a;112:286–292. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.112.2.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalin NH, Shelton SE, Davidson RJ. Cerebrospinal fluid corticotropin-releasing hormone levels are elevated in monkeys with patterns of brain activity associated with fearful temperament. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47:579–585. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00256-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalin NH, Shelton SE, Rickman M, Davidson RJ. Individual differences in freezing and cortisol in infant and mother rhesus monkeys. Behav Neurosci. 1998b;112:251–254. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.112.1.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buss KA, Davidson RJ, Kalin NH, Goldsmith HH. Context-specific freezing and associated physiological reactivity as a dysregulated fear response. Dev Psychol. 2004;40:583–594. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.4.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kagan J, Reznick S, Snidman N. Biological Bases of Childhood Shyness. Science. 1988;240:167–171. doi: 10.1126/science.3353713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt LA, Fox NA, Schulkin J, Gold PW. Behavioral and psychophysiological correlates of self-presentation in temperamentally shy children. Dev Psychobiol. 1999;35:119–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davidson RJ, Lewis DA, Alloy LB, Amaral DG, Bush G, Cohen JD, et al. Neural and behavioral substrates of mood and mood regulation. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:478–502. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01458-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drevets WC. Functional anatomical abnormalities in limbic and prefrontal cortical structures in major depression. Prog Brain Res. 2000;126:413–431. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(00)26027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwartz CE, Wright CI, Shin LM, Kagan J, Rauch SL. Inhibited and uninhibited infants “grown up”: adult amygdalar response to novelty. Science. 2003;300:1952–1953. doi: 10.1126/science.1083703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalin NH, Shelton SE, Davidson RJ. The role of the central nucleus of the amygdala in mediating fear and anxiety in the primate. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5506–5515. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0292-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davidson RJ, Jackson DC, Kalin NH. Emotion, plasticity, context, and regulation: perspectives from affective neuroscience. Psychol Bull. 2000;126:890–909. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.6.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Izquierdo A, Suda RK, Murray EA. Bilateral orbital prefrontal cortex lesions in rhesus monkeys disrupt choices guided by both reward value and reward contingency. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7540–7548. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1921-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rolls ET. The functions of the orbitofrontal cortex. Brain Cogn. 2004;55:11–29. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2626(03)00277-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schoenbaum G, Setlow B, Ramus SJ. A systems approach to orbitofrontal cortex function: recordings in rat orbitofrontal cortex reveal interactions with different learning systems. Behav Brain Res. 2003;146:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wallis JD, Miller EK. Neuronal activity in primate dorsolateral and orbital prefrontal cortex during performance of a reward preference task. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:2069–2081. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davidson RJ. Anxiety and affective style: role of prefrontal cortex and amygdala. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51:68–80. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Urry HL, van Reekum CM, Johnstone T, Kalin NH, Thurow ME, Schaefer HS, et al. Amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex are inversely coupled during regulation of negative affect and predict the diurnal pattern of cortisol secretion among older adults. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4415–4425. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3215-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stefanacci L, Amaral DG. Topographic organization of cortical inputs to the lateral nucleus of the macaque monkey amygdala: a retrograde tracing study. J Comp Neurol. 2000;421:52–79. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000522)421:1<52::aid-cne4>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carmichael ST, Price JL. Limbic connections of the orbital and medial prefrontal cortex in macaque monkeys. J Comp Neurol. 1995;363:615–641. doi: 10.1002/cne.903630408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Porrino LJ, Crane AM, Goldman-Rakic PS. Direct and Indirect Pathways from the Amygdala to the Frontal Lobe in Rhesus Monkeys. J Comp Neurol. 1981;198:121–136. doi: 10.1002/cne.901980111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Machado CJ, Bachevalier J. Non-human primate models of childhood psychopathology: the promise and the limitations. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2003;44:64–87. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baxter MG, Parker A, Lindner CC, Izquierdo AD, Murray EA. Control of response selection by reinforcer value requires interaction of amygdala and orbital prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4311–4319. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04311.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paxinos G, Huang XF, AWT . The rhesus monkey brain in stereotaxic coordinates. San Diego: Academic Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalin NH, Shelton SE, Davidson RJ, Kelley AE. The primate amygdala mediates acute fear but not the behavioral and physiological components of anxious temperament. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2067–2074. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-02067.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Welch PD. The use of Fast Fourier Transform for the estimation of power spectra: a method based on time averaging over short, modified periodograms. IEEE Transactions on Audio and Electroacoustics. 1967;15:70–73. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Butter CM, Snyder DR, McDonald JA. Effects of Orbital Frontal Lesions on Aversive and Aggressive Behaviors in Rhesus Monkeys. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1970;72:132–144. doi: 10.1037/h0029303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vasa RA, Grados M, Slomine B, Herskovits EH, Thompson RE, Salorio C, et al. Neuroimaging correlates of anxiety after pediatric traumatic brain injury. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:208–216. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00708-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quirk GJ, Garcia R, Gonzalez-Lima F. Prefrontal Mechanisms in Extinction of Conditioned Fear. Biol Psychiatry. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Izquierdo A, Suda RK, Murray EA. Comparison of the effects of bilateral orbital prefrontal cortex lesions and amygdala lesions on emotional responses in rhesus monkeys. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8534–8542. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1232-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Butter CM, Snyder DR. Alterations in Aversive and Aggressive Behaviors following Orbital Frontal Lesions in Rhesus Monkeys. ACTA Neurobiol Exp. 1972;32:525–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rudebeck PH, Buckley MJ, Walton ME, Rushworth MF. A role for the macaque anterior cingulate gyrus in social valuation. Science. 2006;313:1310–1312. doi: 10.1126/science.1128197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meunier M, Bachevalier J, Murray EA, Malkova L, Mishkin M. Effects of aspiration versus neurotoxic lesions of the amygdala on emotional responses in monkeys. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:4403–4418. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Izquierdo A, Murray EA. Combined unilateral lesions of the amygdala and orbital prefrontal cortex impair affective processing in rhesus monkeys. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91:2023–2039. doi: 10.1152/jn.00968.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buss KA, Schumacher JR, Dolski I, Kalin NH, Goldsmith HH, Davidson RJ. Right frontal brain activity, cortisol, and withdrawal behavior in 6-month-old infants. Behav Neurosci. 2003;117:11–20. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.117.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davidson RJ. Anterior Cerebral Asymmetry and the Nature of Emotion. Brain Cogn. 1992;20:125–151. doi: 10.1016/0278-2626(92)90065-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davidson RJ, Kalin NH, Shelton SE. Lateralized effects of diazepam on frontal brain electrical asymmetries in rhesus monkeys. Biol Psychiatry. 1992;32:438–451. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(92)90131-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]