Total Synthesis of Vinblastine, Related Natural Products,and Key Analogues and Development of Inspired Methodology Suitablefor the Systematic Study of Their Structure–Function Properties

JustinE Sears

Dale L Boger

Dale L. Boger. E-mail:boger@scripps.edu.

Received 2014 Nov 1; Issue date 2015 Mar 17.

This is an open access article published under an ACS AuthorChoiceLicense, which permits copying and redistribution of the article or any adaptations for non-commercial purposes.

Conspectus

Biologically active natural products composed of fascinatinglycomplex structures are often regarded as not amenable to traditionalsystematic structure–function studies enlisted in medicinalchemistry for the optimization of their properties beyond what mightbe accomplished by semisynthetic modification. Herein, we summarizeour recent studies on theVinca alkaloids vinblastineand vincristine, often considered as prototypical members of suchnatural products, that not only inspired the development of powerfulnew synthetic methodology designed to expedite their total synthesisbut have subsequently led to the discovery of several distinct classesof new, more potent, and previously inaccessible analogues.

With use of the newly developed methodology and in addition toongoing efforts to systematically define the importance of each embeddedstructural feature of vinblastine, two classes of analogues alreadyhave been discovered that enhance the potency of the natural products>10-fold. In one instance, remarkable progress has also been madeon the refractory problem of reducing Pgp transport responsible forclinical resistance with a series of derivatives made accessible onlyusing the newly developed synthetic methodology. Unlike the removalof vinblastine structural features or substituents, which typicallyhas a detrimental impact, the additions of new structural featureshave been found that can enhance target tubulin binding affinity andfunctional activity while simultaneously disrupting Pgp binding, transport,and functional resistance. Already analogues are in hand that aredeserving of full preclinical development, and it is a tribute tothe advances in organic synthesis that they are readily accessibleeven on a natural product of a complexity once thought refractoryto such an approach.

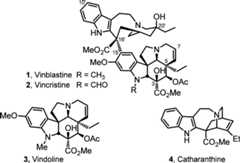

Originally isolated fromCatharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don,1−3 vinblastine(1) and vincristine (2) not only representthe most widely recognized members of theVinca alkaloidsbut also one of the most important contributions that plant-derivednatural products have made to cancer chemotherapy (Figure1).4−6 First introduced into the clinic over 50 years ago,their biological properties were among the first to be shown to arisefrom perturbations in microtubule dynamics that lead to inhibitionof mitosis. Even by today’s standards, both vinblastine andvincristine are efficacious clinical drugs and are used in combinationtherapies for treatment of Hodgkin’s disease, testicular cancer,ovarian cancer, breast cancer, head and neck cancer, and non-Hodgkin’slymphoma (vinblastine) or in the curative treatment regimens for childhoodlymphocytic leukemia and Hodgkin’s disease (vincristine). They,as well as their biological target tubulin, remain the subject ofextensive and continuing biological and synthetic investigations becauseof their clinical importance in modern medicine, low natural abundance,and fascinatingly complex dimeric alkaloid structure.7−16

Figure 1.

Naturalproduct structures.

Vinblastine and vincristineshare an identical upper velbanaminesubunit and contain nearly identical vindoline-derived lower subunitsthat differ only in the nature of the indoline N-substituent, bearingeither a methyl (vinblastine) or formyl (vincristine) group (Figure1). We reported the development of concise totalsyntheses of (−)- andent-(+)-vindoline17,18 enlisting a tandem intramolecular [4 + 2]/[3 + 2] cycloadditioncascade of 1,3,4-oxadiazoles19−25 in which the fully functionalized pentacyclic ring system is constructedin a single step. This occurs with formation of three rings and fourC–C bonds and sets all six stereocenters within the centralring of vindoline, including its three quaternary centers (Figure2). Moreover, the cycloaddition cascade introduceseach substituent, each functional group, each embedded heteroatom,and all the necessary stereochemistry for direct conversion of thecycloadduct to vindoline. The reaction cascade is initiated by a [4+ 2] cycloaddition reaction of a 1,3,4-oxadiazole with a tethereddienophile, which entailed the use of an electron-rich enol etherwhose reactivity and regioselectivity were matched to react with theelectron-deficient 1,3,4-oxadiazole in an inverse electron demandDiels–Alder reaction. Loss of N2 from the initialcycloadduct provides a carbonyl ylide, which undergoes a subsequent1,3-dipolar cycloaddition with a tethered indole.16 For3, the diene and dienophile substituentscomplement and reinforce the [4 + 2] cycloaddition regioselectivitydictated by the linking tether, the intermediate 1,3-dipole is stabilizedby the complementary substitution at the dipole termini, and the tethereddipolarophile (indole) complements the [3 + 2] cycloaddition regioselectivitythat is set by the linking tether. The relative stereochemistry ofthe cascade cycloadduct is controlled by a combination of the dienophilegeometry and an exclusive indole endo [3 + 2] cycloaddition dictatedby the dipolarophile tether and sterically directed to the face oppositethe newly formed fused lactam. This methodology provided the basisfor an 11-step total synthesis of (−)- andent-(+)-vindoline.18

Figure 2.

Key cycloaddition cascade.

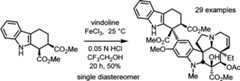

Central to the further advancementof this work was the use ofa biomimetic9 Fe(III)-promoted couplingof vindoline with catharanthine26,27 and the additionaldevelopment of a subsequent in situ Fe(III)-mediated hydrogen-atominitiated free radical alkene oxidation for C20′-alcohol introduction27 that allows for their single-step incorporationinto total syntheses of vinblastine, related natural products includingvincristine, and key analogues (Figure3).16

Figure 3.

First generation total synthesis of vinblastine.

A subsequent asymmetric variantof this approach was developedin which the tether linking the initiating dienophile and 1,3,4-oxadiazolebears a chiral substituent that sets the absolute stereochemistryof the remaining six stereocenters in the cascade cycloadducts, providingtwo distinct and concise asymmetric total syntheses of vindoline (Figure4).28,29 Since the approach enlisted ashortened dienophile tether that resulted in both good facial controland milder reaction conditions for the cascade cycloaddition, itsimplementation for the synthesis of vindoline required the developmentof a ring expansion reaction to provide a six-membered ring suitablyfunctionalized for introduction of the Δ6,7-doublebond found in the core structure of the natural product. Two uniqueapproaches were developed that defined our use of a protected hydroxymethylgroup as the substituent that controls the stereochemical course ofthe cycloaddition cascade. The first entailed a facile tautomerizationof a reactive α-amino aldehyde generated from the primary alcohol,which is trapped as a remarkableN,O-ketal that undergoes a subsequent hydrolytic ring expansion uponfurther activation of the primary alcohol.28,29 The second approach relied upon a thermodynamically controlled reversiblering opening reaction of an intermediate aziridinium ion for whichthe stereochemical features of the reactions are under stereoelectroniccontrol.29 In the course of these studies,several analogues of vindoline were prepared containing deep-seatedstructural changes presently accessible only by total synthesis.19−21

Figure 4.

Keyelements of the asymmetric total synthesis approaches.

Prior to these efforts, the majority of vinblastineanalogues wereprepared by semisynthetic modification of peripheral substituents(tailoring effects), with the disclosure of a limited number of analoguesthat contain deep-seated structural changes.30−33 As detailed herein, the powerfulintramolecular [4 + 2]/[3 + 2] cycloaddition cascade has providedaccess not only to a series of analogues bearing systematic changesto the C5 ethyl substituent34 but to aseries of analogues bearing deep-seated structural modifications tothe vindoline core ring system.35 Theselatter efforts represent one of few examples of productive core structureredesign of a natural product.

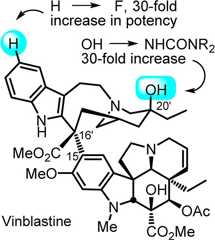

Similarly, detailed herein areefforts to address the major limitationto the continued clinical use of vinblastine and vincristine, whichis the emergence of resistance mediated by overexpression of the drugefflux pump phosphoglycoprotein (Pgp). The identification of structuralanalogues that might address such resistance has remained a majorfocus of the field and would represent a major advance for oncologytherapeutics. With this objective in mind and by virtue of the uniquemethodology developed, we disclosed a series of C20′ urea derivatives36−38 that not only possess extraordinary potency but also exhibit furtherimproved activity against a Pgp overexpressing vinblastine-resistanthuman tumor cell line, displaying improved potency (10–30-fold)and a reduced difference in activity against a matched sensitive andresistant human tumor cell line (HCT116 vs HCT116/VM46, 10–20-foldvs 100-fold difference for vinblastine).38 Although this site is known to be critical to the biological propertiesof vinblastine and is found to be deeply embedded in the tubulin boundcomplex, this study represented the first systematic examination ofanalogues bearing alternative C20′ functionality.

Ashighlighted earlier, a powerful Fe(III)-promoted coupling ofcatharanthine with vindoline generating anhydrovinblastine26 was enlisted and combined with a newly developedin situ Fe(III)/NaBH4-promoted oxidation to provide vinblastinein a single operation (Figure5).27 This development not only converted the syntheticefforts into one capable of use for the systematic exploration ofthe vinblastine structure but also assured that supplies of any analogueneeded for preclinical studies or clinical introduction could be accessedby total synthesis. Consequently, in addition to its use in the completionof the total syntheses of vinblastine (12 steps), vincristine, anda series of additional naturally occurringVinca alkaloids,16 the approach also permits the incorporationof vindoline analogues containing single site peripheral changes tothe structure as well as more deep-seated changes to the vindolinecore accessible only by total synthesis.

Figure 5.

Single-step couplingand in situ oxidation and representative vinblastineanalogues prepared by total synthesis.

An early example of the power of the approach entailed systematicreplacements of the vindoline C5 ethyl group, which were introducedas alternative substituents on the oxadiazole tethered dienophilein the cascade cycloaddition substrate.34 Their examination revealed the surprising importance of the C5 ethylsubstituent where even conservative methyl (10-fold), hydrogen (100-fold),or propyl replacements (10-fold) led to significant reductions inactivity (Figure6).34

Figure 6.

Probingthe importance of the C5 ethyl group.

Further representative of the opportunities the work hasprovidedand complementary to the vindoline 6,5-DE ring system, 5,5-, 6,6-,and the reversed 5,6-membered DE ring system analogues that containdeep-seated changes to the core structure were prepared (Figure5).35 Preparation of theseanalogues, not accessible from natural product sources, further demonstratesthe versatility of the intramolecular [4 + 2]/[3 + 2] cycloadditioncascade. Both the naturalcis and unnaturaltrans 6,6-membered DE ring systems proved accessible, withthe latter unnatural stereochemistry representing a surprisingly effectiveclass for analogue design. After Fe(III)-promoted coupling with catharanthineand in situ oxidation to provide the corresponding vinblastine analogues,their evaluation provided unanticipated insights into how the structureof the vindoline subunit contributes to activity. Two potent analoguespossessing two different unprecedented modifications to the vindolinesubunit core architecture were discovered that matched the potencyof the comparison natural products. Remarkably, both lack the 6,7-doublebond whose removal in vinblastine leads to a 100-fold loss in activity,and both represent the most dramatic departures from the structureof vindoline of those examined to date. Thus, although single functionalgroup removals from the vinblastine lower subunit typically resultin pronounced and additive losses in activity,28 two unprecedented deep-seated structural changes to thecore structure were found that maintain potent activity. Significantlyand unlike modifications of peripheral substituents (tailoring effects),core structure redesign in such complex natural products is rarelyexplored, and the results in this series indicate this may offer farmore opportunities than most might anticipate.35

Ongoing efforts have also begun to define catharanthinesubstituentsthat are required for the Fe(III)-promoted biomimetic coupling withvindoline, and these include (1) a probe of the importance of theC16′ methyl ester and requirement for a C16′ electron-withdrawinggroup for coupling,39 and (2) a Hammettseries of C10′ indole substituents where electron-donatingsubstituents were found to maintain and electron-withdrawing substituentsto progressively slow the rate and efficiency of coupling.40 The former unexpectedly revealed that even conservativereplacements of the vinblastine C16′ methyl ester with an ethylester (10-fold), a cyano group (100-fold), an aldehyde (100-fold),a hydroxymethyl group (1000-fold), or a primary carboxamide (>1000-fold)led to surprisingly large reductions in biological activity, indicatingthat the C16′ methyl ester is not only required for the biosyntheticcoupling but uniquely integral to the expression of vinblastine’sbiological properties (Scheme1).39

Scheme 1.

The latter study, which includedan examination of the impact ofcatharanthine C10′ and C12′ indole substituents on theFe(III)-mediated coupling with vindoline, led to the discovery andcharacterization of two new exciting derivatives, 10′-fluorovinblastineand 10′-fluorovincristine (Figure7).40 In addition to defining a pronounced unanticipatedsubstituent effect on the biomimetic coupling that helped refine itsmechanism,41 fluorine substitution at C10′was found to uniquely enhance the activity 8-fold against both a sensitive(IC50 = 800 pM, HCT116) and a vinblastine-resistant tumorcell line (IC50 = 80 nM, HCT116/VM46). As depicted in theX-ray structure of vinblastine bound to tubulin, this site residesat one end of the upper portion of the T-shaped conformation of thetubulin-bound molecule, suggesting that the 10′-fluorine substituentmakes critical contacts with the protein at a hydrophobic site uniquelysensitive to steric interactions. With the development of an effectivesingle-step coupling and in situ oxidation protocol for convergentanalogue assemblage, the synthesis and evaluation of a systematicseries of C10′ and C12′ analogues were possible. AlthoughC12′ substituents were not well tolerated, C10′ substituentswere. Moreover and with the provision that C10′ polar substituentsare not well tolerated, the activity of the vinblastine C10′derivatives in cell-based assays exhibited no apparent relationshipto the electronic character of the substituents but rather exhibitedactivity that correlates with their size and shape [activity for analogueR = H < F > Cl > Me, Br ≫ I, SMe (10-fold) ≫CN (100-fold)].Thus, small hydrophobic C10′ substituents are tolerated withone derivative exceeding (R = F) and several matching the potencyof vinblastine (R = Cl, Me, Br vs H), whereas those bearing the larger(R = I, SMe) or rigidly extended (R = CN) substituents proved to be10–100-fold less potent. With a recognition that the 10′-fluorosubstitution conveys uniquely potent activity to suchVinca alkaloids, 10′-fluorovincristine was also prepared. Thus,Fe(III)-promoted coupling (70%) of synthetic 10-fluorocatharantinewith syntheticN-desmethylvindoline16 and subsequent in situ Fe(III)-mediated oxidation provided10′-fluoro-N1-desmethylvinblastine,which was formylated to provide synthetic 10′-fluorovincristine.Like 10′-fluorovinblastine, 10′-fluorovincristine exhibitedexceptional activity in the cell-based functional assays, inhibitingtumor cell growth 8-fold more potently than vincristine itself (Figure7).40

Figure 7.

10′-Fluorovinblastineand 10′-fluorovincristine.

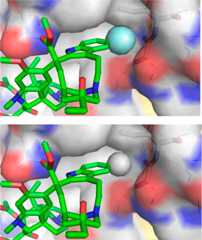

Although the enhanced oxidative metabolic stability of the10′-fluoroderivatives may contribute to the increased potency, the lack of similareffects with closely related substituents indicate that an effectunique to the fluorine substitution is responsible. We have suggestedthat this is derived from the interaction of a perfectly sized hydrophobicsubstituent further stabilizing the compound binding with tubulinat a site exquisitely sensitive to steric interactions. Comparisonmodels of the 10′ substituent analogues built from the X-raystructure of tubulin-bound vinblastine39 illustrated a unique fit for 10′-fluorovinblastine (Figure8).40

Figure 8.

Space filling model ofthe 10′-fluoro binding site of 10′-fluorovinblastine(R = F, top) generated by adding the fluorine substituent to the X-raystructure of tubulin-bound vinblastine43 (R = H, bottom).40 Comparison modelswhere R = Cl, Br, and I illustrated the unique fit for F, and thecomplexes exhibited increasingly larger destabilizing steric interactionsas the substituent size progressively increased.

In order to confirm that the exceptional activity observedin ourlab would be observed elsewhere, we had vinblastine and 10′-fluorovinblastineexamined in a more comprehensive human tumor cell line panel includingcell lines of clinical interest from breast, lung, colon, prostate,and ovary tissue (Figure9) graciously conductedat Bristol-Myers Squibb.42 10′-Fluorovinblastineexhibited remarkable potency (avg IC50 = 300 pM), beingon average 30-fold more potent than vinblastine (avg IC50 = 10 nM) and exceeding our more conservative initial observations.

Figure 9.

10′-Fluorovinblastinehuman tumor cell growth inhibition.

A further delineation of the scope of aromatic substratesthatparticipate with catharanthine in the Fe(III)-mediated coupling reaction,the definition of its key structural features required for participationin the reaction, and its extension to a generalized indole functionalizationreaction that bears little structural relationship to catharanthinewere defined.41 In addition to revealingthat the exclusive diastereoselectivity of the coupling reaction thatinstalls the key C16′ center is controlled by the catharanthine-derivedcoupling intermediate, the studies provided key insights into themechanism of the Fe(III)-mediated coupling reaction of catharanthine,suggesting that the reaction conducted in acidic aqueous buffer mayresult from a single-electron indole oxidation and may be radicalmediated. Just as importantly, the studies provide new opportunitiesfor the synthesis of previously inaccessibleVinca alkaloid analogues (Scheme2) and definedpowerful new methodology for the synthesis of indole-containing naturalproducts.41

Scheme 2.

Similarly, detailedinvestigations of the second stage of the couplingprocess, the Fe(III)-mediated free radical oxidation of the anhydrovinblastinetrisubstituted alkene to introduce the vinblastine C20′ tertiaryalcohol, revealed insights into not only its mechanism but also thesynthesis of previously inaccessible vinblastine analogues. Initialstudies revealed that it is a free radical mediated oxidation reaction,that the reaction is initiated by the addition of NaBH4 to the Fe(III) salt, and that reactions in the absence of air (O2) led to reduction of the double bond (Figure10).16 Subsequent studies providedadditional details of the mechanism of the reaction, entailing a hydrogenatom transfer (HAT) initiated free radical reaction,44 and defined a new method for the direct functionalizationof unactivated alkenes.36 Included in thesestudies was a definition of the alkene substrate broad scope, thereaction’s extensive functional group tolerance, the establishmentof exclusive Markovnikov addition regioselectivity, the use of a widerange of alternative free radical traps for O, N, S, C, and halidesubstitution, an examination of the Fe(III) salt and the hydride sourcebest suited to initiate the reaction, the introduction of alternativereaction solvents beyond the water and aqueous buffer27 originally disclosed, and the exploration of catalyticvariants of the reactions.36 The reactionwas extended to a powerful Fe(III)/NaBH4-mediated freeradical hydrofluorination of unactivated alkenes using Selectfluoras the fluorine atom source.45 Unlike thetraditional and unmanageable free radical hydrofluorination of alkenes,the Fe(III)/NaBH4-mediated reaction is conducted underexceptionally mild conditions (0 °C, 5 min, CH3CN/H2O), uses a technically nondemanding reaction protocol, isconducted open to the air with water as a cosolvent, demonstratesan outstanding substrate scope and functional group tolerance, andis suitable for18F introduction (t1/2 =110 min) used in PET imaging.45

Figure 10.

Hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) free radical oxidation of anhydrovinblastineand generalization of the methodology for unactivated alkene functionalization.

Our interest in this Fe(III)/NaBH4-mediated reactionemerged not only from its use in accessing vinblastine but from theopportunity it presented for the late-stage, divergent46 preparation of otherwise inaccessible vinblastineanalogues incorporating alternative C20′ functionality. Althoughthis site is known to be critical to the properties of vinblastineand is found deeply embedded in the tubulin bound complex (Figure11),43 prior explorationof C20′ substituent effects was limited to semisynthetic O-acylationof the C20′ alcohol, its elimination and subsequent alkenereduction, or superacid-catalyzed additions.47 These invariably led to substantial reductions in biological potencyof the resulting derivative, albeit with examination of only a limitednumber of analogues. Consequently and in the course of the developmentof the Fe(III)/NaBH4-mediated alkene functionalizationreaction, its use was extended to the preparation of a series of keyvinblastine analogues bearing alternative C20′ functionality(e.g., N3, NH2, and SCN vs OH).36 Those of initial interest included the C20′ azideand amine, both of which proved to be approximately 100-fold lesspotent than vinblastine and 10-fold less potent than 20′-deoxyvinblastine.However, acylation of the C20′ amine improved activity 10-fold36 and installation of the unsubstituted C20′urea or thiourea provided compounds that nearly matched the potencyof vinblastine itself (Figure11).36,37 The requisite NH of the internal nitrogen of the latter series presumablybest recapitulates the H-bond donor property of the vinblastine C20′alcohol.

Figure 11.

(top) Initial C20′ vinblastine analogues. (bottom) X-raystructure43 of vinblastine bound to tubulinhighlighting the region surrounding vinblastine C20′ site.

On the basis of these resultsand with the further observationthat the site had an apparent pronounced impact on Pgp transport,we conducted a systematic exploration of C20′ amine, urea,and thiourea derivatives, which provided C20′ urea-based analoguesthat not only substantially exceed the potency of vinblastine butalso exhibited good activity against a Pgp overexpressing, vinblastine-resistanttumor cell line. Thus, members in this group not only exceed the potencyof vinblastine (10-fold) but exhibit even further improved activityagainst vinblastine-resistant cell lines (100-fold) in some cases,partially overcoming overexpressed Pgp transport.37,38

Just as remarkably and in contrast to expectations based onthesteric constraints of the tubulin binding site surrounding the vinblastineC20′ center depicted in the X-ray cocrystal structure of atubulin bound complex,43 large C20′urea derivatives are accommodated (e.g., biphenyl), exhibiting potentfunctional activity in cell-based proliferation assays and effectivelybinding tubulin.37

Continued andongoing studies have provided even more potent analoguesas superb candidate drugs, especially for vinblastine-resistant relapsetumors (Figure12). Thus, a series of disubstitutedC20′-urea derivatives of vinblastine were prepared from 20′-aminovinblastine,accessible through the unique Fe(III)/NaBH4-mediated alkenefunctionalization reaction of anhydrovinblastine. They were foundto not only possess extraordinary potency (IC50 = 40–450pM) but also exhibit further improved activity against a Pgp overexpressingvinblastine-resistant cell line.38 Threesuch analogs were examined across a panel of 15 tumor cell lines graciouslyconducted at Bristol-Myers Squibb,38,42 and each displayedremarkably potent cell growth inhibition activity (avg IC50 = 200–300 pM vs avg vinblastine IC50 = 6.1 nM)against a broad spectrum of clinically relevant human cancer celllines, being on average 20–30-fold more potent than vinblastine(range of 10–200-fold more potent). Significantly, the analoguesalso display further improved activity against the vinblastine-resistantHCT116/VM46 cell line that bears the clinically relevant overexpressionof Pgp, exhibiting IC50 values on par with that of vinblastineagainst the sensitive HCT116 cell line, 100–200-fold greaterthan the activity of vinblastine against the resistant HCT116/VM46cell line, and display a reduced 10–20-fold activity differentialbetween the matched sensitive and resistant cell lines (vs 100-foldfor vinblastine).38 Clearly, the C20′position within vinblastine represents a key site amenable to functionalizationcapable of improving tubulin binding affinity, substantially enhancingbiological potency, and simultaneously decreasing binding and relativePgp transport central to clinical resistance. Compound5 was found to bind tubulin with a higher affinity than vinblastine,confirming that its enhanced potency observed in the cell growth functionalassays correlates with its target tubulin binding affinity.38 Remarkable in these developments is the observationthat the activity against the vinblastine-resistant, Pgp overexpressingcell line uniquely and progressively improves as the terminal nitrogenof the urea is substituted (R = H, H < R = H, Me < R = Me, Me),diminishes smoothly with introduction of polarity, and smoothly increaseswith introduction of increasing π-hydrophobic substitution reflectingtunable and now predictable structural features that enhance tubulinbinding and simultaneously diminish Pgp binding and transport.

Figure 12.

DisubstitutedC20′ urea derivatives of vinblastine.

What is most remarkable about these advances and althoughit couldnot have been imagined at the stage we initiated our efforts, theC20′ analogues of vinblastine are available in three stepsfrom commercially available materials (Scheme3). Although vinblastine is a true trace natural product, representing0.00025% of the dried leaf weight of the periwinkle, its biosyntheticprecursors catharanthine and vindoline are the major alkaloid componentsof the plant. They are readily available, relatively inexpensive startingmaterials. As a result, such C20′ analogues are not only readilyaccessible using the unique chemistry we introduced but also inexpensiveto prepare on scales needed for preclinical development. Thus, theinnovative chemistry developed in route to the total synthesis ofvinblastine–the Fe(III)-mediated single-step coupling of catharanthineand vindoline that proceeds with complete control of the pivotal C16′stereochemistry and the in situ Fe(III)-mediated hydrogen atom transferfree radical functionalization (Markovnikov hydroazidation)36 of the key C20′ center–permitsthe exploration of exciting analogues previously unimaginable.48

Scheme 3.

Not only does this methodologymimic the biosynthetic pathway leadingto vinblastine that has been presumed to be mediated by enzymes, butit is of special note that the diastereoselectivity of the Fe(III)-mediatedcoupling and subsequent oxidation reproduces the relative abundanceof vinblastine and leurosidine (C20′ diastereomer) found inthe plant. Moreover, it is known that catharanthine and vindolineare stored in plants spatially separated from one another.49 This provocatively suggests that the low naturalabundance of vinblastine (and leurosidine) may arise not from an orchestratedenzymatic coupling and subsequent functionalization of catharanthineand vindoline but rather by a stress-induced mixing of the two precursorsin the presence of Fe(III) and air. Perhaps the chemistry we havedeveloped is not simply biomimetic but constitutes nonenzymatic chemistryactually involved in the plant production of vinblastine.

Conclusions andOutlook

Those reading this Account may think the [4 + 2]/[3+ 2] cycloadditioncascade is powerful methodology and that vindoline and vinblastinerepresent perfect applications in which to showcase its potential.Truth is that it was the natural product targets vindoline and vinblastine,their importance in modern medicine, and the potential for their improvementsthat inspired the discovery of the synthetic methodology. Not onlyis the full pentacyclic skeleton of vindoline assembled in a singlecycloaddition cascade, but each substituent, each functional group,each embedded heteroatom, and all the necessary stereochemistry areincorporated into the substrate and the cycloaddition cascade cycloadducttailored for direct conversion to vindoline. It is methodology createdfor the intended target. Combined with the development of a powerfulsingle-step Fe(III)-promoted coupling of catharanthine with vindolineand a newly developed in situ Fe(III)/NaBH4-promoted C20′oxidation, the approach provides vinblastine and its analogues in8–13 steps. With use of the methodology and in addition tosystematically defining the importance of each embedded structuralfeature of vinblastine, two classes of analogues have already beendiscovered that enhance the potency of the natural products >10-fold.In one instance, progress has also been made on the refractory problemof reducing Pgp transport responsible for resistance with a seriesof C20′ amine derivatives uniquely accessible using the newlydeveloped methodology. Unlike the removal of vinblastine structuralfeatures or substituents, which typically has a detrimental impact,the addition of new features can enhance target tubulin binding affinityand functional activity and, in selected instances,50 simultaneously disrupt Pgp binding, transport, and functionalresistance. Already analogues are in hand that are deserving of preclinicaldevelopment, and it is a tribute to the advances in organic synthesisthat they are accessible even on a natural product of a complexityonce thought refractory to such an approach.

Acknowledgments

We gratefullyacknowledge the financial support of the NationalInstitutes of Health (CA115526 and CA042056, DLB).

Biographies

Dale L. Boger is the Richard & Alice Cramer Chairin Chemistry at The Scripps Research Institute (1990-present) wherehe also serves as Chairman (2012–present) of the Departmentof Chemistry. He received his BS in Chemistry from the Universityof Kansas (1975) where he worked with Professor A. W. Burgstahlerand his Ph.D. in Chemistry from Harvard University (1980) workingwith Professor E. J. Corey. He was on the faculty at the Universityof Kansas and Purdue University before joining TSRI in 1990.

Justin E. Sears received his BS inChemistry fromHaverford College (2010) where he worked with Professor Frances Blase.He is currently a Ph.D. student at The Scripps Research Institute(2010–present) with Professor Boger.

The authorsdeclare no competing financial interest.

Special Issue

Published as part oftheAccounts of Chemical Research special issue “Synthesis,Design, and Molecular Function”.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

References

- Noble R. L.; Beer C. T.; Cutts J. H.Role of chance observations in chemotherapy:Vinca rosea. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci.1958, 76, 882–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble R. L.Catharanthus roseus (vinca rosea): Importance and valueof a chance observation. Lloydia1964, 27, 280–281. [Google Scholar]

- Svoboda G. H.; Nuess N.; Gorman M.Alkaloidsof Vinca rosea Linn. (Catharanthus roseus G. Don.).V. Preparation and characterizationof alkaloids. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. Sci. Ed.1959, 48, 659–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuss N.; Neuss M.N.. Therapeutic useof bisindole alkaloids from catharanthus. In The Alkaloids; Brossi A., Suffness M., Eds.; Academic: San Diego, CA, 1990; Vol. 37, pp 229–240. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce H. L.Medicinal chemistryof bisindole alkaloids from Catharanthus. In The Alkaloids; Brossi A., Suffness M., Eds.; Academic: San Diego, CA, 1990; Vol. 37, pp 145–204. [Google Scholar]

- Kuehne M. E.; Marko I.. Syntheses of vinblastine-typealkaloids. In The Alkaloids; Brossi A., Suffness M., Eds.; Academic: San Diego, CA, 1990; Vol. 37, pp 77–132. [Google Scholar]

- Fahy J.Modificationsin the “upper” velbenamine part of the Vinca alkaloidshave major implications for tubulin interacting activities. Curr. Pharm. Des.2001, 7, 1181–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potier P.Synthesisof the antitumor dimeric indole alkaloids from catharanthus species(vinblastine group). J. Nat. Prod.1980, 43, 72–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kutney J. P.Plant cellculture combined with chemistry: a powerful route to complex naturalproducts. Acc. Chem. Res.1993, 26, 559–566. [Google Scholar]

- Langlois N.; Gueritte F.; Langlois Y.; Potier P.Applicationof a modificationof the Polonovski reaction to the synthesis of vinblastine-type alkaloids. J. Am. Chem. Soc.1976, 98, 7017–7024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutney J. P.; Hibino T.; Jahngen E.; Okutani T.; Ratcliffe A. H.; Treasurywala A. M.; Wunderly S.Total synthesis of indole and dihydroindolealkaloids. IX. Studies on the synthesis of bisindole alkaloids inthe vinblastine-vincristine series. The biogenetic approach. Helv. Chim. Acta1976, 59, 2858–2882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehne M. E.; Matson P. A.; Bornmann W. G.Enantioselective syntheses of vinblastine,leurosidine, vincovaline and 20′-epi-vincovaline. J. Org. Chem.1991, 56, 513–528. [Google Scholar]

- Bornmann W. G.; Kuehne M. E.A common intermediate providing syntheses of ψ-tabersonine,coronaridine, iboxyphylline, ibophyllidine, vinamidine, and vinblastine. J. Org. Chem.1992, 57, 1752–1760. [Google Scholar]

- Yokoshima S.; Ueda T.; Kobayashi S.; Sato A.; Kuboyama T.; Tokuyama H.; Fukuyama T.Stereocontrolledtotal synthesis of (+)-vinblastine. J. Am. Chem.Soc.2002, 124, 2137–2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar];Additionally, see:;Kuboyama T.; Yokoshima S.; Tokuyama H.; Fukuyama T.Stereocontrolled totalsynthesis of (+)-vincristine. Proc. Natl. Acad.Sci. U.S.A.2004, 101, 11966–11970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnus P.; Stamford A.; Ladlow M.Synthesisof the antitumor bisindolealkaloid vinblastine: diastereoselectivity and solvent effect on thestereochemistry of the crucial C-15-C-18′ bond. J. Am. Chem. Soc.1990, 112, 8210–8212. [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa H.; Colby D. A.; Seto S.; Va P.; Tam A.; Kakei H.; Rayl T. J.; Hwang I.; Boger D. L.Total synthesisof vinblastine, vincristine, related natural products, and key structuralanalogues. J. Am. Chem. Soc.2009, 131, 4904–4916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa H.; Elliott G. I.; Velcicky J.; Choi Y.; Boger D. L.Total synthesisof (−)- andent-(+)-vindoline and relatedalkaloids. J. Am. Chem. Soc.2006, 128, 10596–10612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y.; Ishikawa H.; Velcicky J.; Elliott G. I.; Miller M. M.; Boger D. L.Total synthesisof (−)- andent-(+)-vindoline. Org. Lett.2005, 7, 4539–4542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Z.; Ishikawa H.; Boger D. L.Total synthesis of natural (−)-andent-(+)-4-desacetoxy-6,7-dihydrovindorosine andnatural andent-minovine: oxadiazole tandem intramolecularDiels–Alder/1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction. Org. Lett.2005, 7, 741–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott G. I.; Velcicky J.; Ishikawa H.; Li Y.; Boger D. L.Total synthesisof (−)- andent-(+)-vindorosine: tandem intramolecularDiels–Alder/1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction of 1,3,4-oxadiazoles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed.2006, 45, 620–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa H.; Boger D. L.Total synthesis of natural (−)- andent-(+)-4-desacetoxy-5-desethylvindoline. Heterocycles2007, 72, 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott G. I.; Fuchs J. R.; Blagg B. S. J.; Ishikawa H.; Tao H.; Yuan Z.; Boger D. L.Intramolecular Diels–Alder/1,3-dipolarcycloaddition cascade of 1,3,4-oxadiazoles. J. Am. Chem. Soc.2006, 128, 10589–10595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie G. D.; Elliott G. I.; Blagg B. S. J.; Wolkenberg S. E.; Soenen D. B.; Miller M. M.; Pollack S.; Boger D. L.IntramolecularDiels–Alder and tandem intramolecular Diels–Alder/1,3-dipolarcycloaddition reactions of 1,3,4-oxadiazoles. J. Am. Chem. Soc.2002, 124, 11292–11294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boger D. L.Diels–Alderreactions of azadienes. Tetrahedron1983, 39, 2869–2939. [Google Scholar]

- Boger D. L.Diels–Alderreactions of heterocyclic azadienes. Chem. Rev.1986, 86, 781–793. [Google Scholar]

- Vukovic J.; Goodbody A. E.; Kutney J. P.; Misawa M.Production of 3′,4′-anhydrovinblastine:a unique chemical synthesis. Tetrahedron1988, 44, 325–331. [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa H.; Colby D. A.; Boger D. L.Directcoupling of catharanthineand vindoline to provide vinblastine: total synthesis of (+)- andent-(−)-vinblastine. J. Am.Chem. Soc.2008, 130, 420–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki Y.; Kato D.; Boger D. L.Asymmetrictotal synthesis of vindorosine,vindoline, and key vinblastine analogues. J.Am. Chem. Soc.2010, 132, 13533–13544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato D.; Sasaki Y.; Boger D. L.Asymmetric total synthesis of vindoline. J. Am. Chem. Soc.2010, 132, 3685–3687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehne M. E.; Bornmann W. G.; Marko I.; Qin Y.; Le Boulluec K. L.; Frasier D. A.; Xu F.; Malamba T.; Ensinger C. L.; Borman L. S.; Huot A. E.; Exon C.; Bizzarro F. T.; Cheung J. B.; Bane S. L.Syntheses and biological evaluationof vinblastine congeners. Org. Biomol. Chem.2003, 1, 2120–2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki T.; Yokoshima S.; Simizu S.; Osada H.; Tokuyama H.; Fukuyama T.Synthesisof (+)-vinblastine and its analogues. Org. Lett.2007, 9, 4737–4740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss M. E.; Ralph J. M.; Xie D.; Manning D. D.; Chen X.; Frank A. J.; Leyhane A. J.; Liu L.; Stevens J. M.; Budde C.; Surman M. D.; Friedrich T.; Peace D.; Scott I. L.; Wolf M.; Johnson R.Synthesisand SAR of vinca alkaloid analogues. Bioorg.Med. Chem. Lett.2009, 19, 1245–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gherbovet O.; Coderch C.; Alvarez M. C. G.; Bignon J.; Thoret S.; Martin M.-T.; Guéritte F.; Gago F.; Roussi F.Synthesisand biological evaluation of a new series of highly functionalized7′-homo-anhydrovinblastine derivatives. J. Med. Chem.2013, 56, 6088–6100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Va P.; Campbell E. L.; Robertson W. M.; Boger D. L.Total synthesisand evaluation of a key series of C5-substituted vinblastine derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc.2010, 132, 8489–8495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleicher K. D.; Sasaki Y.; Tam A.; Kato D.; Duncan K. K.; Boger D. L.Total synthesis and evaluation of vinblastine analoguescontaining systematic deep-seated modifications in the vindoline subunitring system: core redesign. J. Med. Chem.2013, 56, 483–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leggans E. K.; Barker T. J.; Duncan K. K.; Boger D. L.Iron(III)/NaBH4-mediated additions to unactivatedalkenes: synthesis of novel20′-vinblastine analogues. Org. Lett.2012, 14, 1428–1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leggans E. K.; Duncan K. K.; Barker T. J.; Schleicher K. D.; Boger D. L.A remarkable series of vinblastineanalogues displayingenhanced activity and an unprecedented tubulin binding steric tolerance:C20′ urea derivatives. J. Med. Chem.2013, 56, 628–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker T. J.; Duncan K. K.; Otrubova K.; Boger D. L.Potent vinblastineC20′ ureas displaying additionally improved activity againsta vinblastine-resistant cancer cell line. ACSMed. Chem. Lett.2013, 4, 985–988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam A.; Gotoh H.; Robertson W. M.; Boger D. L.Catharanthine C16substituent effects on the biomimetic coupling with vindoline: preparationand evaluation of a key series of vinblastine analogues. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.2010, 20, 6408–6410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh H.; Duncan K. K.; Robertson W. M.; Boger D. L.10′-Fluorovinblastineand 10′-fluorovincristine: synthesis of a key series of modifiedVinca alkaloids. ACS Med. Chem. Lett.2011, 2, 948–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh H.; Sears J. E.; Eschenmoser A.; Boger D. L.New insights intothe mechanism and an expanded scope of the Fe(III)-mediated vinblastinecoupling reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc.2012, 134, 13240–13243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- We thank Gregory Viteand Robert Borzillerifor arranging and overseeing this assessment and Craig Fairchild,Kathy Johnson, and Russell Peterson for conducting the testing atBristol–Myers Squibb.

- Gigant B.; Wang C.; Ravelli R. B. G.; Roussi F.; Steinmetz M. O.; Curmi P. A.; Sobel A.; Knossow M.Structural basis forthe regulation of tublin by vinblastine. Nature2005, 435, 519–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki K.; Wan K. K.; Oppedisano A.; Crossley S. W. M.; Shenvi R. A.Simple, chemoselective hydrogenationwith thermodynamic stereocontrol. J. Am. Chem.Soc.2014, 136, 1300–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar];Alsosee:Lo J.C.; Yabe Y.; Baran P. S.A practical and catalytic reductive olefin coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc.2014, 136, 1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker T.J.; Boger D. L.Fe(III)/NaBH4-mediated free radical hydrofluorinationof unactivated alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.2012, 134, 13588–13591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boger D. L.; Brotherton C. E.Total synthesisof azafluoranthene alkaloids: rufescineand imelutine. J. Org. Chem.1984, 49, 4050–4055. [Google Scholar]

- Duflos A.; Kruczynski A.; Baret J.-M.Novel aspects ofnatural and modifiedVinca alkaloids. Curr. Med. Chem., Anti-CancerAgents2002, 2, 55–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell E.L.; Skepper C. K.; Sankar K.; Duncan K. K.; Boger D. L.TransannularDiels–Alder/1,3-dipolar cycloaddition cascade of 1,3,4-oxadiazoles:total synthesis of a unique set of vinblastine analogues. Org. Lett.2013, 15, 5306–5309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roepke J.; Salim V.; Wu M.; Thamm A. M. K.; Murata J.; Ploss K.; Boland W.; De Luca V.Vinca drug componentsaccumulate exclusively in leaf exudates of Madagascar periwinkle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.2010, 107, 15287–15292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Once in a while you receive avalued gift if you ask the right question at the right time. Personalcommunication: Otis, Hutchinson, KS (1971).