How unrealistic optimism is maintained in the face of reality

Tali Sharot

Christoph W Korn

Raymond J Dolan

Tali Sharot, 12 Queen Square, London, WCN 3BG, UK,t.sharot@ucl.ac.uk

These authors contributed equally

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS T.S. conceived the study. T.S and C.W.K. designed the study, developed stimuli, gathered and analyzed behavioral and fMRI data. T.S., C.W.K and R.J.D. interpreted the data and wrote the paper.

Users may view, print, copy, download and text and data- mine the content in such documents, for the purposes of academic research, subject always to the full Conditions of use:http://www.nature.com/authors/editorial_policies/license.html#terms

Abstract

Unrealistic optimism is a pervasive human trait influencing domains ranging from personal relationships to politics and finance. How people maintain unrealistic optimism, despite frequently encountering information that challenges those biased beliefs, is unknown. Here, we provide an explanation. Specifically, we show a striking asymmetry, whereby people updated their beliefs more in response to information that was better than expected compared to information that was worse. This selectivity was mediated by a relative failure to code for errors that should reduce optimism. Distinct regions of the prefrontal cortex tracked estimation errors when those called for positive update, both in highly optimistic and low optimistic individuals. However, highly optimistic individuals exhibited reduced tracking of estimation errors that called for negative update within right inferior prefrontal gyrus. These findings show that optimism is tied to a selective update failure, and diminished neural coding, of undesirable information regarding the future.

People’s estimations of the future are often unrealistically optimistic1-5. A problem that has puzzled scientists for decades is why human optimism is so pervasive, when reality continuously confronts us with information that challenges these biased beliefs5. According to influential learning theories agents should adjust their expectations when faced with disconfirming information6,7. However, this normative account is challenged by findings showing that providing people with evidence that disconfirms their positive outlook often fails to engender realistic expectations. For example, highlighting previously unknown risk factors for diseases is surprisingly ineffective at altering peoples’ optimistic perception of their medical vulnerability8,9. Even experts show worrying optimistic biases. For instance, financial analysts expect improbably high profits3 and family-law attorneys underestimate the negative consequences of divorce2.

The wider societal importance of these errors derives from the fact that they reduce precautionary actions, such as practicing safe sex or saving for retirement8,9. On the upside, optimistic expectations can lower stress and anxiety, thereby promoting health and well-being10-12. While the existence of unrealistic optimism has been extensively documented1-5, for review13&14, the biological and computational principles that help to maintain optimistically biased predictions in the face of reality are unknown5. Importantly, such biases are not explained by theories assuming equal learning across outcome valence6,7.

There is now a rich literature indicating that learning from information that disconfirms one’s expectations is mediated by regions involved in error processing and conflict detection, including anterior cingulate cortex, adjacent medio-frontal regions and lateral prefrontal regions15-20. Here, we tested whether a failure to alter optimistic predictions when presented with disconfirming data was mediated by differential error processing in response to information that was better, or worse, than expected.

We combined a novel learning paradigm with functional brain imaging. Our task enabled us to quantify how much participants adjusted their beliefs in response to new information. While optimism is defined both as overestimation of positive future events and underestimation of future negative events1, we focused here on the latter as this is strongly related to a concern that people do not take necessary action to protect themselves against hazards9. We obtained fMRI (functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging) data while participants estimated their likelihood of experiencing 80 different types of adverse life events (e.g. Alzheimer’s disease, robbery etc. – seeSupplementary List of Stimuli). After each trial, participants were presented with the average probability of that event occurring to an individual living in the same socio-cultural environment as the participants (Fig. 1a – paradigm). We then assessed whether participants used this information to update their predictions by subsequently asking them in a second session to provide estimates of their likelihood of encountering all 80 events.

Figure 1.

Task design. (a) On each trial participants were presented with a short description of one of 80 adverse life events and asked to estimate how likely this event was to occur to them. They were then presented with the average probability of that event occurring to a person like themselves, living in the same socio-cultural environment. For each event an estimation error term was calculated as the difference between the participant’s estimation and the information provided. The second session was the same as the first session. For each event an update term was calculated as the difference between the participant’s first and second estimations. (b,c) Examples of trials for which the participant’s estimate was (b) higher or (c) lower than the average probability. Here, for illustration purposes, the blue and red frames denote the participant’s response (either an overestimation or underestimation, respectively). The blue and red filled boxes denote information that calls for an adjustment in an (b) optimistic (desirable) or (c) pessimistic (undesirable) direction.

RESULTS

Behaviour: selective updating

Our behavioural results revealed a striking asymmetry in belief updating. Participants learned to a greater extent from information offering an opportunity to adopt more optimistic expectations (hereafter “desirable information”Fig. 1b) than from information that challenged participants’ rosy outlook (hereafter “undesirable information”Fig. 1c). Specifically, participants were more likely to update their beliefs when the average probability of experiencing a negative life event was lower than the participants’ own probability estimate (mean absolute update from first to second session = 11.2), relative to a situation where the average probability was higher (update = 7.7, t (18) = 4.4, P < 0.001;Supplementary Fig. 1a). This robust effect was observed in 79% of the participants (Fig. 2a) and replicated across additional behavioural studies (Supplementary Behavioural Studies I & II). The difference was also significant when updates were calculated as the percentages of the initial estimate, (t (18) = 4.7, P < 0.001;Supplementary Fig. 1b).

Figure 2.

Behaviorally observed bias. (a) After receiving (desirable) information that presented an opportunity to adopt a more optimistic outlook, participants updated their estimations to a greater extent than after receiving (undesirable) information that called for a more pessimistic estimate. This asymmetric update was observed in 15 out of 19 participants. For group means seeSupplementary Fig. 1a. (b) Betas indicating the association between update and estimation errors on an individual basis showed that estimation errors predicted update to a greater extent when participants received desirable information than when they received undesirable information. This asymmetry is observed in all 19 participants. For group means seeSupplementary Fig. 1d.

One obvious explanation for this pattern of findings is that a greater weighting given to desirable information simply reflects differential memory for desirable compared to undesirable information. This was not the case. After the scanning session, participants were asked to indicate the actual probability (as previously presented) of each event occurring to an average person in the same socio-cultural environment. Memory errors were calculated as the absolute difference between the actual probability previously presented and the participants’ recollection of that statistical number. Participants remembered information presented to them equally well irrespective of whether it was desirable or undesirable (t (18) = 0.75, P > 0.4;Supplementary Fig. 1c, alsoSupplementary Behavioural Studies I & II).

Furthermore, post-scanning questionnaire scores showed that any differential updating across valence was not explained by differences in emotional arousal, extent of negative valence, familiarity, or past experience with the adverse life event (Supplementary Results). Specifically, the difference in absolute update for events for which participants received desirable and undesirable information remained significant after entering all these scores as covariates (F(1, 13) = 9.7, P < 0.01). Thus, differential update could not be explained by differences in the degree of adversity of the events or familiarity/ past experience with the events.

Importantly, positively biased updating was not due to differences in the underlying true probabilities (base rates) of the events. The difference in update for events in which participants received desirable and undesirable information remained significant even after entering the true probabilities of the events as covariates (F (1,17) = 6.04, P < 0.05). In other words, how common or rare the occurrence of an event is had no bearing on selective updating. Neither were there differences in the number of trials (t (18) = 0.02, P > 0.9), the magnitude of the initial estimation errors (t (18) = 1.85, P > 0.05), or reaction times (t (18) = 1.04, P > 0.3) when participants received desirable or undesirable information. Finally, asymmetric updating was not explained by a differential processing of high and low percentages, as this was controlled for by asking participants to estimate their likelihood of encountering the adverse event on half of the trials, and to estimate their likelihood of not encountering the adverse event on the other half of the trials (seeSupplementary Results).

Formal models suggest that learning is mediated by a prediction error signal that quantifies a difference between expectation and outcome7,21,22. We hypothesized that an analogous mechanism underpinned belief update in our task. We formulated the difference between participants’ initial estimations and the information provided in terms of estimation errors (i.e. estimation error = estimation − probability presented). Indeed, estimation errors predicted subsequent updates on an individual level (mean beta from individual linear regressions relating estimation errors to update = 0.53, P < 0.0005). However, the strength of this association was valence-dependent, being greater for information that offered an opportunity to adopt a more optimistic outlook (beta = 0.72), relative to information that called for a more pessimistic outlook (beta = 0.33, t (18) = 5.8, P < 0.0005;Fig. 2bandSupplementary Fig. 1d). Importantly, this difference remained significant after controlling for the true underlying probabilities of events by including them as a factor to the regression analysis (t (18) = 2.6, P < 0.02).

These behavioural findings suggest a likely computational principle that mediates unrealistic optimism. Specifically, they point to estimation errors as providing a learning signal whose impact depends on whether new information calls for an update in an optimistic or pessimistic direction. Consequently, we next examined our fMRI data to identify how BOLD signal tracks estimation errors in response to information that entails either a belief adjustment in an optimistic or in a pessimistic direction.

fMRI: tracking of estimation errors

We first identified voxels where activity tracked desirable or undesirable estimation errors. Trials were partitioned based on whether participants received desirable or undesirable information regarding the future after their first rating. We entered the absolute estimation error on each trial as a parametric regressor modulating the time point when participants were presented with information regarding the average probability of events (seeFig. 1). From this analysis we identified regions where BOLD signal correlated with estimation errors for either desirable or undesirable information on a trial by trial basis (P < 0.05, cluster level corrected after voxel-wise thresholding at P < 0.001).

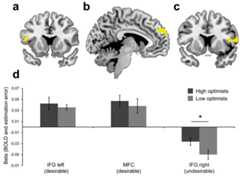

BOLD signal correlated positively with desirable estimation errors in three distinct regions; left inferior frontal gyrus (IFG: peak voxels in Talairach coordinates: −58, 21, −1; k = 274;Fig. 3a), left and right medial frontal cortex / superior frontal gyrus (MFC/SFG: −10, 62, 28; k = 412;Fig. 3b) and right cerebellum (33,−79,−28; k = 185). In addition, BOLD signal correlated negatively with undesirable estimation errors in the right inferior frontal gyrus extending into precentral gyrus and insula (46, 12, 9 & 60, 10, 9; k = 190;Fig. 3c). There were no voxels where activity correlated negatively with desirable errors or positively with undesirable errors. In other words, brain activity increased when the average probability was more desirable than participants’ estimates (in left IFG, bilateral MFC/SFG and right cerebellum) and decreased when it was more undesirable (in right IFG). All of these regions have been previously implicated in error processing in a variety of tasks15-20.

Figure 3.

Brain activity tracking estimation errors. Regions where BOLD signal tracked participants’ estimation errors on a trial by trial basis in response to desirable information regarding future likelihoods included (a) the left IFG and (b) bilateral MFC/SFG; (P < 0.05, cluster level corrected). (c) BOLD signal tracking participants’ estimation errors in response to undesirable information was found in the right IFG/precentral gyrus (P < 0.05, cluster level corrected). (d) Parameter estimates of the parametric regressors in both the left IFG and bilateral MFC/SFG did not differ between individuals who scored high or low on trait optimism. In contrast, in the right IFG a stronger correlation between BOLD activity and undesirable errors was found for individuals who scored low on trait optimism relative to those who scored high. Error bars (s.e.m.). * = P < 0.05, two-tailed independent sample t-test.

As our behavioural findings tied estimation errors to update, it follows that activity that tracks estimation errors should also predict subsequent update. To test this we entered the level of subsequent update as a parametric regressor modulating the time point when participants were first presented with information regarding the average probability of adverse events. We then retrieved the parameter estimates for each participant and each condition in the four functional ROIs (regions of interest) identified above, averaged across all voxels. Indeed, activity in the right IFG predicted update in response to undesirable information (parameter estimates significantly greater than zero; t (18) = 2.2, P < 0.05). Activity in MFC/SFG (t (18) = 2.1, P < 0.05) and right cerebellum (t (18) = 2.4, P < 0.05) predicted update in response to desirable information (in the left IFG parameter estimates were not significantly different from zero).

Trait optimism, biased updating, and BOLD signal

Next, we examined whether the extent to which brain activity tracked estimation errors was related to optimism. We compared betas from the parametric analysis (relating BOLD signal to estimation errors) in each functional ROI (averaged across all voxels) of participants who scored high on trait optimism with those who scored low (according to the Life Orientation Test-Revised scale: LOT-R23). There was no difference between high and low optimists on betas tracking desirable errors in the left IFG (Fig. 3d), bilateral MFC/SFG (Fig. 3d) or cerebellum. Importantly, however, participants who scored high on trait optimism showed a weaker correlation of right IFG activity with undesirable errors relative to those who scored low (Fig. 3d). Specifically, betas indicating a correlation between BOLD signal and undesirable estimation errors in the right IFG showed a weaker inverse relation in high compared to low optimists (t (17) = 2.1, P < 0.05). This difference could not be explained by the magnitude of the initial undesirable estimation errors (P > 0.8) or memory for undesirable information (P > 0.5), as neither differed between groups.

The same finding was obtained when we considered all 4 ROIs together in a single linear regression with group membership (high or low optimism) as the dependent measure, controlling for differential scores (desirable minus undesirable) of memory, familiarity, past experience, vividness and arousal, and extent of initial estimation errors. A stepwise procedure revealed that the best model predicting trait optimism was one that included only betas from the right IFG tracking undesirable estimation errors (beta = 0.46, P < 0.05). This result suggests a specific relationship between trait optimism and a reduced neural coding of undesirable errors regarding the future.

To examine this further we determined whether the optimistic update bias in our task related to how well BOLD activity tracked undesirable errors. Across individuals BOLD signal tracking undesirable estimation errors predicted the observed update bias (desirable update minus undesirable update) in right IFG (partial correlation controlling for behavioural association between estimation errors and update r12.3 = 0.45, P = 0.05). Participants with the largest optimistic update bias failed to track undesirable errors (the correlation between BOLD signal in the right IFG and undesirable errors in these participants was close to zero;Fig. 4a). Participants who did not show selective updating had the strongest relationship between BOLD signal and undesirable estimation errors. Thus, these results suggest that an asymmetry in belief updating is driven by a reduced expression of an error signal in a region implicated in processing undesirable errors regarding the future.

Figure 4.

Optimism and brain activity tracking undesirable estimation errors. (a) Across individuals, the extent of the update bias (difference in update in response to desirable errors minus undesirable errors) correlated with how strong the peak voxel in the right IFG ROI correlated with undesirable errors (r12 = 0.45). Participants showing the greatest optimistic bias in updating showed the weakest tracking of undesirable estimation errors. (d) Furthermore, participants who updated their estimates more in response to undesirable information showed a greater reduction in activity in the right IFG ROI the second time desirable information was presented, relative to the first (r = −0.47).

A final prediction arising from our data is that those participants, who updated their response the most in response to undesirable information, should show greater BOLD reduction the second time undesirable information is presented. The logic here is that a greater update should correspond to smaller estimation errors in response to repeated presentation of information and thus to less overall activity in regions tracking estimation errors to repeated information. To test this we examined the correlation, across participants, between suppression of activity in the right IFG (BOLD signal at second presentation of undesirable information minus BOLD signal at first presentation of undesirable information, averaged across all voxels in the ROI) and degree of update on undesirable trials. We found that participants who showed greater update in response to undesirable information had a greater reduction in activity at the second time-point when undesirable information was presented (r = −0.47, P < 0.05;Fig. 4b). For a description of differential activation during the period when participants thought about encountering the adverse events seeSupplementary Table 1.

DISCUSSION

Our findings offer a mechanistic account of how unrealistic optimism persists in the face of challenging information. We showed that optimism was related to diminished coding of undesirable information about the future, in a region of the frontal cortex (right IFG) identified as sensitive to negative estimation errors. Participants scoring high on trait optimism were worse at tracking undesirable errors in this region, relative to those who scored low. In contrast, tracking of desirable information in regions processing desirable estimation errors (MFC/SFG, left IFG and cerebellum) did not differ between high and low optimists.

Reduced BOLD tracking of undesirable errors in right IFG predicted the extent to which participants selectively updated their beliefs using information that enforced optimism, while (relatively) dismissing information that contradicted it. Importantly, this effect was not explained by how well participants recalled the information presented to them. Neither did it reflect specific characteristics of the adverse events (e.g. familiarity, negativity, arousal, past experience, how rare or common the event is). Thus, unlike predictions from learning theory, where both positive and negative information are given equal weight6,7, we showed a valence-dependent asymmetry in how estimation errors impacted on beliefs about one’s personal future.

Interestingly, our fMRI data revealed that error evoked activity differed in response to desirable and undesirable information regarding possible future outcomes. Segregated regions encoded error-related-activity in response to new information that called for optimistic or pessimistic adjustments. While the left IFG, left and right MFC/SFG and right cerebellum tracked desirable errors, the right IFG tracked undesirable errors. It is worth noting that previous studies have suggested hemispheric asymmetry in processing positive and negative information consistent with that found here in the IFG24. Furthermore, while BOLD signal in regions tracking positive estimation errors increased when the average probability was better than the participant’s estimate, in regions tracking negative estimation errors it decreased when the average probability was worse than expected. In other words, activity increased for a better than expected outcome and dipped for a worse than expected outcome – a pattern resembling that of neurons signalling prediction errors21-22.

All regions identified in this study as coding estimation errors have previously been shown to track errors in different contexts, including errors due to incorrect responses15, errors in expectations in the absence of action16, reversal errors17,18 and prediction errors that code differences between expectations and outcomes19. Note that those errors emerge when outcomes are experienced, and capture differences in expected and real magnitudes. Here, estimation errors captured the difference between participants’ predictions of the likelihood of a possible future outcome and information about the actual probability of experiencing these outcomes. This information was presented in an explicit form that engaged higher cognitive functions, and this is likely to explain the preferential engagement of cortical regions. Our findings suggest that these error signals are subject to motivational modulation (see also20). Specifically, a motivation to adopt the most rewarding (or least aversive) perspective on future outcomes is likely to modulate the impact of an error signal that subsequently influences update. As information regarding hypothetical outcomes is less constrained than actual experiences, the impact of such information may be more easily altered by motivation. It is possible that reduced coding of negative errors is restricted to such cases, and we do not know whether it will generalise to instances where outcomes are in fact experienced.

We previously described a positivity bias in the imagination of future life events, where participants imagined positive future events as closer in time and more vivid than negative events – a bias mediated by activity in rostral anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and amygdala25. Whereas participants in our previous study showed an optimistic bias in unconstrained imagination, here we identified an optimistic learning bias when participants’ beliefs were challenged by new information. These results provide a powerful explanatory framework for how optimistic biases are maintained.

Underestimating susceptibility to negative events can serve an adaptive function by enhancing explorative behaviour and reducing stress and anxiety associated with negative expectations11,12,26. This is consistent with the observation that mild depression is related to a more accurate estimation of future outcomes, and severe depression to pessimistic expectations27. However, any advantage arising out of unrealistic optimism is likely to come at a cost. For example, an unrealistic assessment of financial risk is widely seen as contributing factor to the 2008 global economic collapse28,29. The current study suggests that this human propensity towards optimism is facilitated by the brain’s failure to code errors in estimation when those call for negative updates. This failure results in selective updating, which supports unrealistic optimism that is resistant to change. Dismissing undesirable errors in estimation renders us peculiarly susceptible to view the future through rose coloured glasses.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a Wellcome Trust Program Grant to R. J. Dolan, a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellowship to T. Sharot, and a German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) scholarship to C.W. Korn. We thank S. Fleming for assistance with analysis, P. Dayan for discussion, T. Behrens, D. Schiller, Q. Huys, J. Winston, B. De Martino, S. Fleming, S. Bengtsson, K. Wunderlich, H. Heekeren, S. Kennerley and M. Guitart-Masip for comments on a previous version of this manuscript.

Appendix

METHODS

Participants

Twenty healthy right-handed participants were recruited via the University College London (UCL) psychology subject pool. Data from one participant was lost due to a computer error leaving nineteen participants (age range 19–27, 8 females). All subjects gave informed consent and were paid for their participation. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of UCL.

Stimuli

Eighty short descriptions of negative life events (e.g., car theft, Parkinson’s disease;Supplementary List of Stimuli) were presented in random order via a mirror mounted on the scanner head coil. Stimuli were split into two lists of 40 events each.

For each adverse event the average probability of that event occurring at least once to a person living in the same socio-cultural environment as the participants was determined based on online resources (Office for National Statistics, Eurostat, Pubmed). Very rare or very common events were not included; all events probabilities lay between 10% and 70%. To ensure that the range of possible overestimation equalled the range of possible underestimation, participants were told that the range of probabilities lay between 3% and 77%.

Scanning task

First, participants went through three practice trials. The session began with a short structural scan, followed by four functional runs consisting of 40 trials each (i.e., all 80 events were presented twice). Finally, an additional longer structural scan was performed.

The experimental task is depicted inFigure 1. On each trial a stimulus was presented on screen for 4 sec. Participants were instructed to think of that event happening to them in the future. After these 4 sec participants were to respond in the following manner; in half of the runs (either runs 1&2 or runs 3&4 – counterbalanced across participants) the words “Estimation of happening?” appeared on screen and participants were to enter their estimated likelihood of the event happening to them in the future, and in the other two runs the words “Estimation of NOT happening?” appeared on screen and participants were to enter their estimated likelihood of the event not happening to them in the future. We framed estimations in these two ways so that differential processing of undesirable and desirable information (i.e. overestimation and underestimation of the likelihood of an event) could not be attributed to differential processing of high and low numbers. In case that participants had already experienced an event in their lifetime they were instructed to estimate the likelihood of that event happening (or not happening) to them again in the future.

Participants had up to 6 sec to respond using a button box with four buttons in each hand. Each button corresponded to one digit. The digits 0 through 7 could be used to enter the estimated likelihoods in the “happen” estimation and digits 2 through 9 in the “not happen” estimation. If the participant failed to respond that trial was excluded from all consequent analyses (mean trials with no response = 2.5 trials, SD = 4.0). A fixation cross then appeared for 1–5 sec (jittered). Next, the event description appeared again for 2 sec together with the average probability of that event to occur (or not occur – depending on “happen” or “not happen” sessions). Finally, a fixation cross appeared for 1–3 sec (jittered).

Participants estimated each event twice in two consecutive sessions, which immediately followed one another. One list of 40 stimuli (counterbalanced) was presented during scan 1 and then again during scan 2. The other list was presented during scan 3 and then again during scan 4.

Main behavioural analysis

All statistical percentages and all responses in the “not happen” sessions were transformed into the corresponding numbers of the “happen” sessions by subtracting the respective number from 100. For each event in each session an estimation error term was calculated as the absolute difference between the participant’s estimate and the corresponding statistical probability presented.

| (1) |

For each participant, trials were classified according to whether the participant initially underestimated the probability of the event relative to the average probability (and thus received desirable information;Fig. 1b) or overestimated (thus received undesirable information;Fig. 1c). Trials for which the estimation error was zero were excluded from subsequent analyses (mean = 1.5 trials, SD = 1.6).

We calculated the amount of update as the difference between the first and second estimates.

| (2) |

Average absolute update was compared for trials where participants received desirable and undesirable information using paired sample t-tests across participants.

For each participant a linear regression was conducted entering estimation errors as independent measures and updates as dependent measures. Next, linear regressions were conducted (as above) separately for trials in which participants received desirable information and undesirable information. Further linear regression models with the true underlying probabilities of the event as an additional independent measure were calculated. Across subjects, betas were submitted to paired sample t-tests and one sample t-tests.

Memory test and analysis

After the scanning sessions participants were asked to indicate the actual probability (previously presented) of each event occurring to an average person in the developed world. Memory errors were calculated as the absolute difference between the actual probability previously presented and the participant’s recollection of that statistic.

| (3) |

Memory errors for desirable and undesirable information were compared using a paired sample t-test.

Post scanning questionnaire

Participants were presented with the same trials again on a computer screen and were asked to rate events on five scales: Vividness (How vividly could you imagine this event? From 1 = not vivid to 6 = very vivid); familiarity (Regardless if this event has happened to you before, how familiar do you feel it is to you from TV, friends, movies and so on? From 1 = not at all familiar to 6 very familiar); prior experience (Has this event happened to you before? From 1 = never to 6 = very often); arousal (When you imagine this event happening to you how emotionally arousing is the image in your mind? From 1 = not arousing at all to 6 = very arousing); and negativity (How negative would this event be for you? From 1 = not negative at all to 6 = very negative).

Trait optimism (LOT-R)

Finally, participants completed the LOT-R scale23 that measures trait optimism on a scale from 0 (pessimistic) to 24 (optimistic). Participants were generally optimistic; the mean optimism score was 15.68 (range 7–21, SD = 3.98). We divided participants into those that scored higher than the mean (“high optimism” group n = 11, mean = 18.54) and those that scored lower than the mean (“low optimism” group n = 8, mean = 11.75).

Scanning procedure

Scanning was performed at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging at UCL using a 3T Siemens Allegra scanner with a Siemens head coil. Anatomical images were acquired using MPRage which comprised 1mm thick axial slices parallel to the AC-PC plane. Functional images were acquired as echo-planar (EPI) T2*-weighted images. Time of repetition (TR) = 2.73 sec, time of echo (TE) = 30 ms, flip angle (FA) = 90, matrix = 64 × 64, field of view (FOV) = 192 mm, slice thickness = 2 mm. A total of 42 axial slices (−30° tilt) were sampled for whole brain coverage, in-plane resolution = 3mm × 3mm.

MRI data analysis

Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM5; Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, London, UK,http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) was used for fMRI data analysis. After discarding the first six dummy volumes, images were realigned to the first volume, unwarped, normalised to a standard EPI template based on the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) reference brain, resampled to 2mm × 2mm × 2mm voxels, and spatially smoothed with an isotropic 8 mm full width at half maximum (FWHM) Gaussian kernel.

For each participant we created a time series indicating the temporal position of event presentation, presentation of cue prompting response, motor response, and presentation of information. These were modelled as time periods of 4, 0, 0, and 2 sec, respectively. For all task components (except for motor response) regressors were subdivided into two conditions - trials of events for which participants first received desirable information and trials of events for which they first received undesirable information – resulting in 7 regressors for each session. Time periods were convolved with the canonical hemodynamic response function to create regressors of interest. Motion correction regressors estimated from the realignment procedure were entered as covariates of no interest.

To identify regions tracking estimation errors we entered absolute estimation errors as parametric regressors modulating the time period of desirable and undesirable initial information presentation for each participant (see coloured boxes inFig. 1b,c). For each condition (i.e. for desirable trials and undesirable trials separately) we identified regions where parametric modulation estimates were significantly different from zero (P < 0.05, cluster level corrected; voxels first threshold at P < 0.001, uncorrected). These regions were defined as functional regions of interest (ROIs) for subsequent analyses.

As estimation errors correlated with subsequent updates one would expect that activity in regions tracking estimation errors would also predict subsequent update. To confirm this we entered each participant’s subsequent update on each trial as a covariate modulating the time period of initial information presentation. Estimates from this parametric modulation analysis were averaged for each participant and condition over all voxels in each ROI. The beats were then compared to zero using a one sample t-test (P < 0.05).

To test whether trait optimism was related to how closely BOLD activity tracked desirable and undesirable estimation errors we conducted the following analysis: Estimates from the parametric modulation analysis of estimation errors were averaged for each participant and condition over all voxels in each ROI. These betas were compared for participants in the “high optimism” group (those that scored above the mean on the LOT-R test of trait optimism), with those in the “low optimism” group (those that scored below the mean on the LOT-R) using an independent sample t-test (P < 0.05).

Furthermore, betas from all 4 ROIs were submitted in one linear regression analysis with optimism group membership (high or low) as the dependent measure, controlling for differential scores (desirable minus undesirable) of memory, familiarity, past experience, vividness and arousal, and extent of initial estimation errors. We conducted a stepwise procedure to reveal the best model predicting trait optimism.

The above analysis revealed that the region tracking undesirable errors differentiated between participants who were high and those who were low on trait optimism. We tested whether activity in this region also predicted the extent of behavioural update bias across individuals. To that end, betas relating estimation errors with BOLD signal in the two peaks identified initially from the parametric analysis in this region were correlated with the behavioural update bias (desirable update minus undesirable update). To specifically isolate this relationship, we conducted a linear regression that controlled for betas from the behavioural analysis relating undesirable estimation errors and undesirable update.

Lastly, we tested the hypothesis that greater undesirable update was related to reduced activity in the region tracking undesirable estimation errors in the second session (relative to the first). To that end, we correlated mean updates on undesirable trials across individuals with activity indicating repetition suppression (BOLD activity during second presentation of undesirable information minus BOLD activity first during presentation of that information). Note, this analysis examined the reduction in the magnitude of activity, rather than the correlation of activity with a parametric regressor.

For completeness, we conducted a whole brain exploratory analysis comparing activity during the time participants thought about encountering the adverse event for desirable and undesirable trials (Supplementary Table 1).

All activations are displayed on sections of the standard MNI reference brain. Anatomical labels were assigned using the Talairach daemon (University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio;http://www.talairach.org/) according to peak voxels in Talairach and Tournoux coordinate space.

Footnotes

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Weinstein ND. Unrealistic optimism about future life events. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1980;39:806–820. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker LA, Emery RE. When every relationship is above average: perceptions and expectations of divorce at the time of marriage. Law and Human Behaviour. 1993;17:439–450. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calderon TG. Predictive properties of analysts’ forecasts of corporate earnings. The Mid-Atlantic Journal of Business. 1993;29:41–58. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puri M, Robinson DT. Optimism and economic choice. J. Financial Economics. 2007;86:71–99. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armor DA, Taylor SE. In: Heuristics and Biases: The Psychology of Intuitive Judgement. Gilovich T, Griffin DW, Kahneman D, editors. Cambridge Univ. Press; New York: 2002. pp. 334–438. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pearce JM, Hall G. A model for pavlovian learning: variations in the effectiveness of conditioned but not of unconditioned stimuli. Psychol. Rev. 1980;87:532–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sutton RS, Barto AG. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction. MIT Press; Cambridge, Massachusetts: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Reis-Bergan M. The effect of risk communication on risk perceptions: the significance of individual differences. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs. 1999;25:94–100. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinstein ND, Klein WM. Resistance of personal risk perceptions to debiasing interventions. Health Psychol. 1995;14:132–140. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.2.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor SE, Brown JD. Illusion and well-being: a social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychol. Bull. 1988;103:193–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheier MF, Matthews KA, Owens JF, Magovern GJ, Sr., Lefebvre RC, Abbott RA, Carver CS. Dispositional optimism and recovery from coronary artery bypass surgery: the beneficial effects on physical and psychological wellbeing. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989;57:1024–1040. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.57.6.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor SE, Kemeny ME, Reed GM, Bower JE, Gruenewald TL. Psychological resources, positive illusions and health. Am. Psychol. 2000;55:99–109. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharot T. The Optimism Bias. Pantheon Books; NY, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang EC. Optimism & Pessimism: Implications for Theory, Research, and Practice. 1st ed. American Psychological Association (APA); 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greening SG, Finger EE, Mitchell DGV. Parsing decision making processes in prefrontal cortex: response inhibition, overcoming learned avoidance, and reversal learning. Neuroimage. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.09.017. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeung N, Holroyd CB, Cohen JD. ERP correlates of feedback and reward processing in the presence and absence of response choice. Cereb. Cortex. 2005;15:535–544. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cools R, Clark L, Owen AM, Robbins TW. Defining the neural mechanisms of probabilistic reversal learning using event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:4563–4567. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-11-04563.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell DGV, et al. Adapting to dynamic stimulus-response values: differential contributions of inferior frontal, dorsomedial, and dorsolateral regions of prefrontal cortex to decision making. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:10827–10834. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0963-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor SF, Stern ER, Gehring WJ. Neural systems for error monitoring: recent findings and theoretical perspectives. Neuroscientist. 2007;13:160–72. doi: 10.1177/1073858406298184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bengtsson SL, Lau HC, Passingham RE. Motivation to do well enhances responses to errors and self-monitoring. Cereb. Cortex. 2009;19:797–804. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schultz W, Dayan P, Montague RR. A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science. 1997;275:1593–1599. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5306.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schultz W. Predictive reward signal of dopamine neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1998;80:1–27. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1994;67:1063–1078. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davidson RJ. Hemispheric asymmetry and emotion. In: Davidson RJ, Ekman P, editors. Questions about emotions. MIT Press; Massachusetts: 1983. pp. 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharot T, Riccardi AM, Raio CM, Phelps EA. Neural mechanisms mediating optimism bias. Nature. 2007;450:102–105. doi: 10.1038/nature06280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Varki A. Human uniqueness and the denial of death. Nature. 2009;460:7256–684. doi: 10.1038/460684c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strunk DR, Lopez H, DeRubeis RJ. Depressive symptoms are associated with unrealistic negative predictions of future life events. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006;44:861–882. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shefrin H. In: Voices of wisdom: understanding the global financial crisis. Siegel LB, editor. Research foundation of CFA institute; 2010. pp. 224–256. Available athttp://ssrn.com/abstract=1523931. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ubel P. Human nature and the financial crisis. Forbes. 2009 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.