Detectingh-index manipulation through self-citation analysis

Christoph Bartneck

Servaas Kokkelmans

Corresponding author.

Received 2010 Jul 15; Issue date 2011.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abstract

Theh-index has received an enormous attention for being an indicator that measures the quality of researchers and organizations. We investigate to what degree authors can inflate theirh-index through strategic self-citations with the help of a simulation. We extended Burrell’s publication model with a procedure for placing self-citations, following three different strategies: random self-citation, recent self-citations andh-manipulating self-citations. The results show that authors can considerably inflate theirh-index through self-citations. We propose theq-index as an indicator for how strategically an author has placed self-citations, and which serves as a tool to detect possible manipulation of theh-index. The results also show that the best strategy for an highh-index is publishing papers that are highly cited by others. The productivity has also a positive effect on theh-index.

Keywords:h-Index, Self-citation, Manipulation,q-Index, Simulation

Introduction

In the competitive academic world, it is necessary to assess the quality of researchers and their organizations. The allocation of resources and individual careers depend on it. In the UK, for example, the use of bibliometric indicators for the national Research Assessment Exercise (RAE) has long been discussed [17]. Efforts have been made to make such assessments as objective as possible. While the productivity could relatively easy be measured by counting publications, assessing the impact of research often relied on the count of citations received. In 2005, Hirsch [9] proposed theh-index, which tries to bring productivity and impact into a balance.

It is hard to underestimate the effect that his proposal had on the field of scientometrics. Google Scholar lists 1,130 citations for his original paper as of June 16th, 2010. Some authors even divide the research field into a pre and post Hirsch period [14]. A wealth of extensions, modifications have since been proposed [12,13] and also new indicators have been developed, such as theg-index [4]. These modification and new indicators are intended to improve the originalh-index. The arrival of the Publish and Perish software made the calculation of these diverse indicators accessible to a more general public.

An elaborated review on the benefits and problems of theh-index is available [5]. We will focus on the problem of self-citations, which has polarized the research community. On the one hand, self-citations can be considered a natural part of scientific communication, while others condemn it as a means to artificially inflate bibliometric indicators. Besides this fundamental divide about the role an importance of self-citations, there are also practical issues. Reliably filtering self-citations is currently only practical in highly consistent data sets, such as from the Web of Science. But even Thomson-Reuter had to introduce the Researcher ID to indentify unique researchers, in particular if researchers have the same name. The Web of Science might be a useful data set for traditional disciplines, such as Physics, but its coverage is insufficient for research fields in which conference proceedings play an important role [11]. Google Scholar (GS) offers the widest coverage of academic communication, but filtering self-citations from its results is currently not reliably possible. And maybe we even should not filter them, since they form an organic part of the citation process [8] and self-citations make up for up to 36% of all citations [1]. This might make it difficult to sharpen theh-index by excluding self-citation as it was already proposed [15]. It has also been demonstrated that results from GS can potentially be manipulated through mock publication [10].

Still it would be useful to be able to distinguish between authors that cite their previous work to clarify the relationship with the paper at hand and authors that strategically cite their papers even if they are not directly relevant to the current paper.

One method of strategically manipulating theh-index is the following: first cite the paper(s) that have currently as many citations as theh-index and then proceed downwards from there. Lets look an example to illustrate this strategy. Figure 1 shows the citation profile for an example author that published 60 papers. His papers are sorted by the citations they have received. He currently has anh-index of 20, which is visualized by the diagonal line. This means that he has at least 20 papers that have each been cited at least 20 times. We will refer to the paper that has the least citations and still contributes to theh-index as theh-paper. In this case it is paper number 20. If he would cite theh-paper and paper number 21, that each have currently 20 citations, then hish-index would increase to 21. He would have 21 papers that each have at least 21 citations. With only investing two self-citations, this author could inflate hish-index by one. A more subtle strategy would be to only cite papers that currently have fewer citations than the author’sh-paper since citing already highly cited papers is unlikely to increase theh-index quickly.

Fig. 1.

Citation profile of an example author

Given that up to 36% of all citations are self-citations, the potential inflation of bibliometric indicators could be enormous. We therefore focus on the following research questions:

How much can authors inflate theirh-index through strategic self-citations?

How can we detect strategic self-citation?

What influence has the authors’ productivity, quality, career length, and proportion of self-citations on the authors’h-index?

Method

To be able to investigate how far theh-index can be inflated we need to consider extreme authors that focus all their self-citations on increasing theirh-indexes. We are currently not aware of a sufficient number of such extreme authors to be able to appropriately answer all our research questions with data from real authors. The only exception might be Ike Antkare, an mock scientist who is only citing himself [10] We therefore did no base our analyses on existing authors, but focused on simulated authors.

Wolfgang Glänzel and his co-authors [6,7] proposed a stochastic model for the publishing and citation process. However, here we make use of a more recent stochastic model proposed by Burrell [3], which is better suited for our simulation. The main result of this model as described in Eq.1 defines is the expected number of papers that receive at leastn citations by timeT:

| 1 |

withB(x;a, b) the regularized incomplete beta function defined as

| 2 |

and the gamma function. The model depends on quality parameters which characterize a certain author:

the gamma function. The model depends on quality parameters which characterize a certain author:

- T

is the time passed since the start of the researchers career

- θ

is the productivity (mean number of publications per unit time)

- ν

is the standard shape parameter of the citation distribution (gamma distribution), which is related to its hight.

- 1/α

is the standard scale parameter of the citation distribution (gamma distribution), which is related to its width.

is the mean citation rate (average number of citations per paper per year)

- n

is the number of citations

Equation 1 can be considered as the average citedness of papers from authors of a given quality (see Fig. 2). The graph has the expected shape for citation indexes and appears to match reality. It follows the well documented skew [16] and hence we assume face validity of the model. We invert the expression in Eq.1 to create a theoretical citation profile for an example author characterized by these quality parameters.

Fig. 2.

Average citedness of papers from authors of productivity θ = 3, career lengthT = 20, mean citation rate with ν = 3 and α = 2

with ν = 3 and α = 2

We used Burrell’s model to simulate the publication process of an average author defined through the parameters mentioned above. We added one parameter μ, which is defined as the number of self-citations per paper. For practical reasons, we defined μ as a constant, but it is conceivable that the number of self-citations might change over the duration of a scientist’s career. We implemented three different self-citation strategies:

the author makes μ strategic self citations by the method described above (unfair condition)

the author cites his μ last papers (fair condition)

the author randomly cites μ of papers (random condition)

The fair condition is based on the observation that the number of self-citations is the highest for new papers and declines rapidly over time [1]. The random condition provides us with a baseline against which we can compare the other two conditions. The simulation, implemented in Mathematica, consists of a main loop that cycles for thep published papers from 1 to θ × T through the following steps:

calculate the currenthp-index of the author

calculate the citations received from other researchers through Burrell’s model

place μ self citations through one of the three strategies described above

calculate indicators, such as theq-index described below, for the current state

sum the citations from others and the self-citations

Results

To answer the question how much an authors can inflate theirh-index through self-citations we first would like to present an archetypical author. He publishes three papers per year over a total of 20 years and he makes three self-citations per paper. Figure 3 shows how theh-index develops over the period of publishing each of the 60 papers. After 20 years the author would have anh-index of 19 if he had used the unfair strategy, while a random self-citation strategy would have resulted in anh-index of only 14. Through the strategic placement of his self-citations, he was able to inflate hish-index by 5.

Fig. 3.

Development ofhp-index over published papersp for an author with θ = 3, career lengthT = 20, mean citation rate with ν = 3 and α = 2

with ν = 3 and α = 2

If we now look at the citation index of the unfair author, we notice a humpback around theh-paper, which is in this case the 19th paper (see Fig. 4). An author with a random self-citation strategy does not have such a humpback. This may come at no surprise, since the humpback is a direct result of self-citing papers close to theh-paper.

Fig. 4.

Citation profilec60,i over paper indexi of an author in the unfair and in the random condition with θ = 3, career lengthT = 20, mean citation rate with ν = 3 and α = 2, and for a total number of published papers ofp = θ × T = 60

with ν = 3 and α = 2, and for a total number of published papers ofp = θ × T = 60

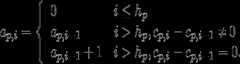

To be able to assess the size of the humpback we propose theq-index. Quasimodo, a fictional character in Victor Hugo’s novel “The Hunchback of Notre Dame”, inspired its name. Quasimodo has a severely hunched back, which reminded us of the humpback in the citation profile. In comparison to the penalty system proposed by Burrell [2] theq-index does not decrease the citation count, but it introduces a stand alone indicator for the self-citation behavior.

Theq-index can be calculated as follows. First, sort all papers (i = 1…p) of an author or organization, given a certain number of already published papersp, according to their citations in a descending order:cp,i. This creates the well known citation profiles, as shown in Fig. 1. This citation profile is characterized byh-indexhp. For each self-citation of a paper that has equal or fewer citations than thehp-paper, the author receives aq-score. Thisq-score is calculated by dividing 1 by the number of different citations scores between thehp-paper and the paper that receives the self-citation. If the author cites thehp-paper(s) then the score will be . If he cites paper(s) that have the next fewer citations, then he receives a score of

. If he cites paper(s) that have the next fewer citations, then he receives a score of and so forth. Next papersi which have the same citation scorecp,i as the previous one, receive the sameq-score. The formal definition is given by:

and so forth. Next papersi which have the same citation scorecp,i as the previous one, receive the sameq-score. The formal definition is given by:

| 3 |

withap,i given by

| 4 |

Note that we only take into account theq-scores for the actually cited papersi, and therefore the summedq-score that an author receives for publishing a new paperp can only range between 0 and μ.

Lets take an example to illustrate theq-scores. Figure 5 shows the citation profile of our archetypical unfair author. Thex axis lists theq-scores that this author receives for citing his own papers. Notice that the author does not receive anyq-score for self-citing papers that have more citations than thehp-paper. These papers are on the left of the diagonalh-line. Citing these papers does not directly inflate theh-index and are therefore not considered when calculatingq-scores. Also notice that papers that have the same number of citations also receive the sameq-scores. Their order can be assumed to be random and hence it would not be fair to give them differentq-scores.

Fig. 5.

Unfair citation profile of Fig. 4 with theq-scores on thex axis

We plotted theq-scores in the order in which the papers were published (see Fig. 6). If the author publishes a new paper that cites three of his own papers, then the threeq-scores he received are summed. The paper index on thex axis thereby defines the order in which the papers were published. Initially, all three self-citing strategies produce the sameq-scores. This comes at no surprise since the fourth published paper can only cite its three predecessors. Only starting from the fifth paper, the author can choose which paper not to cite. A few papers later, we find significant differences between the three self-citation conditions. The unfair author receives highq-scores with very little spread, since he is always citing very close to thehp-paper.

Fig. 6.

Summedq-score indexes over published paperp, for the unfair, fair and random condition

The author with a fair self-citing strategy receives lower and lowerq-scores (see Fig. 6). This can be explained by the fact that the total number of publications grows much faster than theh-index. The proportion of papers that have fewer citations than thehp-paper (to the right of thehp-paper) to the papers that have equal or more citations than thehp-paper (from thehp-paper to the left) is increasing (see Fig. 7). The new papers that the fair author cites become further and further away from thehp-paper and hence attract lower and lowerq-scores.

Fig. 7.

Proportion of papers with fewer citations than theh-paper

An author with a random self-citation strategy has a much higher spread in hisq-scores, but they also appear to decrease. The growing number of papers that have fewer citations than thehp-paper can also explain this trend. The papers in this long tail cause lower and lowerq-scores (see Fig. 7).

We propose theq-index as the summedq-scores the author received for each self-citations ranging from 0 to the total number of self-citations μ, in published paperj, to a paper in the citation profile indexed byij,s. This is normalized by the number of published papersp:

| 5 |

The normalization byp assures that theq-index is approximately constant over all published papers if an author consistently cites according to the unfair scheme. This linear behavior can be seen from the unnormalizedq-index in Fig. 8 for the unfair condition, while in the fair and the random condition it flattens out and are in general far below the unnormalizedq-index of the unfair condition (see Fig. 8). Interestingly, the curve for the fair and the random condition are very close to each other. It might be difficult to distinguish between authors that use these two strategies. Theq-index’s range follows as:

| 6 |

Theq-index should be accompanied by the standard deviation of the summedq-scores. For our example of our archetypical author, theq-indexes atp = 60 are available in Table 1. Theq-index of the fair and random condition are within one standard deviation from each other. We may therefore conclude that theq-index is not able to detect a significant differences between these two conditions. Theq-index for the unfair condition is approximately ten standard deviations away from theq-index of the random condition and approximately four standard deviations away from the fair condition. It would be very unlikely if the difference observed would be due to chance. To test this hypothesis, we performed the non-parametric Mann–Whitney test, since we cannot assume a normal distribution of the data. The distributions in the random and unfair conditions differed significantly (Mann–WhitneyU = 41.5, n1 = n2 = 60, P < 0.01, two-tailed).

Fig. 8.

Unnormalizedq-indexp × Qp over published papersp, for the unfair, fair and random condition

Table 1.

q-Index and standard deviation across all conditions

| Condition | Q | Std dev. |

|---|---|---|

| Random | 0.475 | 0.076 |

| Fair | 0.509 | 0.149 |

| Unfair | 1.176 | 0.179 |

Next, we were interested in how the different parameters of Burrell’s model influence the development of theh-index. We started by varying the productivity θ from one paper per year to eighteen papers per year. These values seem plausible minimum and maximum values. Of course, an director of a research institute that insists on co-authorship of every paper produced in his/her institute may exceed these boundary conditions, but the analysis of honorary authorship are not in the focus of our study. The other parameters remained at their stereotypical setting of career lengthT = 20, mean citation rate with ν = 3 and α = 2. Figure 9 shows thath-index quickly increases 0 < θ < 5 and then slowly flattens. An author that publishes six papers per year will have an more than double theh-index compare to an author that publishes only one paper per year. The unfair strategy benefits in particular by an increased productivity, since more published papers also mean more self-citations.

with ν = 3 and α = 2. Figure 9 shows thath-index quickly increases 0 < θ < 5 and then slowly flattens. An author that publishes six papers per year will have an more than double theh-index compare to an author that publishes only one paper per year. The unfair strategy benefits in particular by an increased productivity, since more published papers also mean more self-citations.

Fig. 9.

ah-Index across the productivity θ.b Same, but on a logarithm productivity scale. On this scale, the fair and random citation strategies confirm the straight lines as also observed by Burrell. The unfair strategy, however, clearly deviates from the linear behavior

The next parameter we varied is the career lengthT between 1 and 40 years, which again seemed plausible boundary conditions. The remaining parameters were set to the stereotypical values of θ = 3, mean citation rate with ν = 3 and α = 2. Figure 10 shows a linear increase for theh-index for all three conditions. Theh-score increases by approximately one per year.

with ν = 3 and α = 2. Figure 10 shows a linear increase for theh-index for all three conditions. Theh-score increases by approximately one per year.

Fig. 10.

h-Index across the career lengthT

We varied the number of self-citations per papers μ from one to ten, which appeared to be reasonable limits. The other parameters remained at their stereotypical settings. The results displayed in Fig. 11 show that μ has a smaller effect on theh-index compared to θ andT. In the fair and random condition, the increasing μ results on only a mild increase in theh-index. In the unfair condition, theh-index grows over μ, but again less compared to θ andT. The small effect size is also visible in absolute terms. With ten self-citations per paper, an unfair author is only able to get up to anh-index of around 30, while he can get up to 50 with a publication rate of 18 papers per year.

Fig. 11.

h-Index across the number of self citation μ

Next, we changed the shape parameter ν and the scale parameter α of the citation distribution, keeping in mind that is the mean citation rate, which defines how many citations a paper receives from other researchers. We increased the value for ν and α from one to ten, which appeared reasonable boundary conditions. The other parameters remained at their stereotypical settings. Figure 12 shows that the increasing value for ν increases the number of citations from others, which in turn negates the advantage of strategic self-citations. At ν, there is no more difference between the unfair condition and the other two conditions. For authors that produce highly esteemed works by others, strategic self-citations have little positive effect. Burrell offered a similar result in his Fig. 4(a) he kept α at 5 and increased ν from 5 to 500.

is the mean citation rate, which defines how many citations a paper receives from other researchers. We increased the value for ν and α from one to ten, which appeared reasonable boundary conditions. The other parameters remained at their stereotypical settings. Figure 12 shows that the increasing value for ν increases the number of citations from others, which in turn negates the advantage of strategic self-citations. At ν, there is no more difference between the unfair condition and the other two conditions. For authors that produce highly esteemed works by others, strategic self-citations have little positive effect. Burrell offered a similar result in his Fig. 4(a) he kept α at 5 and increased ν from 5 to 500.

Fig. 12.

h-Index across the height of the citation distribution parameter ν

When increasing the value for α, the mean citations rate drops, which has the opposite effect from increasing ν. And indeed, Fig. 13 shows that theh-index decreases over an increasing value for α. The gap between the unfair condition and the other two conditions increases, indicating that making strategic self-citations becomes increasingly beneficial.

Fig. 13.

h-Index andq-scores across the width of the citation distribution parameter α

To assess how strong the effect of productivity, career length, number of self-citations, and mean citation rate, is on theh-index, we calculated the average change in theh-index as:

| 7 |

wherehk is the theh-index when the parameter (θ, T, μ, ν, α) isk, ranging from 2 to the maximum of the respective parameter. The average and its standard deviation is displayed in Table 2. The mean citation rate has the strongest impact on theh-index. The increase of ν by one increases theh-index on average by four and an increase in α of one decreases theh-index by around two. The second strongest effect stems from the productivity of the author. By publishing one paper more per year, the author’sh-index increases by approximately 1.5. With every year passed, theh-index increases on average by one. The number of self-citations has only a strong effect for authors that strategically place them. For all other authors, it has the smallest benefit.

and its standard deviation is displayed in Table 2. The mean citation rate has the strongest impact on theh-index. The increase of ν by one increases theh-index on average by four and an increase in α of one decreases theh-index by around two. The second strongest effect stems from the productivity of the author. By publishing one paper more per year, the author’sh-index increases by approximately 1.5. With every year passed, theh-index increases on average by one. The number of self-citations has only a strong effect for authors that strategically place them. For all other authors, it has the smallest benefit.

Table 2.

The average and standard deviation for all parameters

and standard deviation for all parameters

| Parameter | Condition | Mean | Std dev. |

|---|---|---|---|

| θ | Unfair | 2.53 | 1.50 |

| Fair | 1.47 | 1.42 | |

| Random | 1.65 | 1.69 | |

| T | Unfair | 1.03 | 0.58 |

| Fair | 0.95 | 0.32 | |

| Random | 0.97 | 0.67 | |

| μ | Unfair | 1.33 | 0.87 |

| Fair | 0.56 | 0.53 | |

| Random | 0.44 | 0.53 | |

| ν | Unfair | 4.11 | 5.99 |

| Fair | 4.11 | 4.51 | |

| Random | 4.00 | 4.58 | |

| α | Unfair | −1.44 | 2.01 |

| Fair | −2.11 | 2.52 | |

| Random | −2.00 | 2.65 |

Conclusions

The results of our simulation show that authors can significantly inflate theirh-index, and possible also other indices, by strategically citing their own publications. Calculating theq-index helps identifying such behavior and plotting the individualq-scores over the sequence of published papers allows us to gain additional insights into the publication history of an author. Theq-index also allows us to run standard statistical test for cases that are ambiguous. The unfair author in our study is an extreme example and real authors might apply more subtle strategies to manipulate theirh-index. Theq-index also conveniently ranges from 1 to μ, which gives it an easy to interpret range. Our simulation is able to provide the benchmark of a random self-citation behavior, which can be used to compare the real authors’q-index against.

Overall we can conclude that the unfair self-citation strategy is mainly useful for authors that are less productive and that attract less citations from others. The most effective method to increase one’sh-index is to produce work that is highly cited by other. The next best strategy is to be productive. The length of the career only has a moderate influence. On average, authors can increase theirh-index by one per year, as it was predicted by Hirsch [9].

This study does have some limitations. We have to acknowledge that our simulations has not yet been verified by comparing its results to data from real authors. However, we hope to test theq-index on real authors in the next phase of our project.

The application of theq-index to real data may proof to be difficult, since it requires knowledge of each publication, including the date of each received citations. While this is relatively easy to accomplish in a simulation, the data from the real world has a tendency to be incomplete and occasionally ambiguous. A first application could be achieved on the well structured data from the Web of Science and in a second phase, attempts could be made to parse the results from Google Scholar.

We also have to consider that the mean citation rate does not model the size of the research community in which a certain author may operate. This potentially influential factor is not part of Burrell’s model and hence we are unable to make any judgements about it. We are also not able to make any judgements about the differences between scientific disciplines.

In essence, we showed that theh-index is vulnerable to manipulations by self-citations. We propose theq-index as a metric to judge how strategic the self-citations of an author have been. In addition, we showed that the best way to increase one’sh-index is to write interesting papers. This might be no surprise, but sometimes it is necessary to even state the obvious.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Contributor Information

Christoph Bartneck, Phone: +31-40-247-5175, Email: c.bartneck@tue.nl.

Servaas Kokkelmans, Phone: +31-40-247-3357, Email: s.kokkelmans@tue.nl.

References

- 1.Aksnes D. A macro study of self-citation. Scientometrics. 2003;56(2):235–246. doi: 10.1023/A:1021919228368. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burrell Q. L. Should the h-index be discounted? ISSI Newsletter. 2007;3-S:65–67. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burrell Q. L. Hirsch’s h-index: A stochastic model. Journal of Informetrics. 2007;1(1):16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.joi.2006.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Egghe L. Theory and practise of the g-index. Scientometrics. 2006;69(1):131–152. doi: 10.1007/s11192-006-0144-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia-Perez M. A multidimensional extension to Hirschs h-index. Scientometrics. 2009;81(3):779–785. doi: 10.1007/s11192-009-2290-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glänzel W., Schoepflin U. A stochastic model for the ageing of scientific literature. Scientometrics. 1994;30(1):49–64. doi: 10.1007/BF02017212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glänzel W., Schubert A. Predictive aspects of a stochastic model for citation processes. Information Processing and Management. 1995;31(1):69–80. doi: 10.1016/0306-4573(94)E0012-Q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glänzel W., Thijs B., Schlemmer B. A bibliometric approach to the role of author self-citations in scientific communication. Scientometrics. 2004;59(1):63–77. doi: 10.1023/B:SCIE.0000013299.38210.74. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirsch J. E. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(46):16569–16572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507655102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Labbe C. Ike Antkare one of the great stars in the scientific firmament. ISSI Newsletter. 2010;6(2):48–52. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meho L. I., Yang K. Impact of data sources on citation counts and rankings of lis faculty: Web of science versus scopus and google scholar. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 2007;58(13):2105–2125. doi: 10.1002/asi.20677. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Noorden R. Metrics: A profusion of measures. Nature. 2010;465:864–866. doi: 10.1038/465864a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panaretos J., Malesios C. Assessing scientific research performance and impact with single indices. Scientometrics. 2009;81(3):635–670. doi: 10.1007/s11192-008-2174-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prathap G. Is there a place for a mock h-index? Scientometrics. 2010;84(1):153–165. doi: 10.1007/s11192-009-0066-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schreiber M. Self-citation corrections for the Hirsch index. Europhysics Letters. 2007;78(3):0002. doi: 10.1209/0295-5075/78/30002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seglen P. O. The skewness of science. Journal of the American Society for Information Science. 1992;43(9):628–638. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(199210)43:9<628::AID-ASI5>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silverman B. W. Comment: Bibliometrics in the context of the UK research assessment exercise. Statistical Science. 2009;24(1):15–16. doi: 10.1214/09-STS285A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]