Eczema Care Online behaviouralinterventions to support self-care for children and young people: two independent,pragmatic, randomised controlled trials

Miriam Santer

Ingrid Muller

Taeko Becque

Beth Stuart

Julie Hooper

Mary Steele

Sylvia Wilczynska

Tracey H Sach

Matthew J Ridd

Amanda Roberts

Amina Ahmed

Lucy Yardley

Paul Little

Kate Greenwell

Katy Sivyer

Jacqui Nuttall

Gareth Griffiths

Sandra Lawton

Sinéad M Langan

Laura M Howells

Paul Leighton

Hywel C Williams

Kim S Thomas

Correspondence to: M Santerm.santer@soton.ac.uk

Corresponding author.

Roles

Accepted 2022 Oct 31; Collection date 2022.

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms ofthe Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others todistribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, providedthe original work is properly cited. See:http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Abstract

Objective

To determine the effectiveness of two online behavioural interventions, one forparents and carers and one for young people, to support eczemaself-management.

Design

Two independent, pragmatic, parallel group, unmasked, randomised controlledtrials.

Setting

98 general practices in England.

Participants

Parents and carers of children (0-12 years) with eczema (trial 1) and young people(13-25 years) with eczema (trial 2), excluding people with inactive or very mildeczema (≤5 on POEM, the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure).

Interventions

Participants were randomised (1:1) using online software to receive usual eczemacare or an online (www.EczemaCareOnline.org.uk) behavioural intervention for eczemaplus usual care.

Main outcome measures

Primary outcome was eczema symptoms rated using POEM (range 0-28, with 28 beingvery severe) every four weeks over 24 weeks. Outcomes were reported by parents orcarers for children and by self-report for young people. Secondary outcomesincluded POEM score every four weeks over 52 weeks, quality of life, eczemacontrol, itch intensity (young people only), patient enablement, treatment use,perceived barriers to treatment use, and intervention use. Analyses were carriedout separately for the two trials and according to intention-to-treatprinciples.

Results

340 parents or carers of children (169 usual care; 171 intervention) and 337 youngpeople (169 usual care; 168 intervention) were randomised. The mean baseline POEMscore was 12.8 (standard deviation 5.3) for parents and carers and 15.2 (5.4) foryoung people. Three young people withdrew from follow-up but did not withdrawtheir data. All randomised participants were included in the analyses. At 24weeks, follow-up rates were 91.5% (311/340) for parents or carers and 90.2%(304/337) for young people. After controlling for baseline eczema severity andconfounders, compared with usual care groups over 24 weeks, eczema severityimproved in the intervention groups: mean difference in POEM score −1.5 (95%confidence interval −2.5 to −0.6; P=0.002) for parents or carers and −1.9 (−3.0 to−0.8; P<0.001) for young people. The number needed to treat to achieve a 2.5difference in POEM score at 24 weeks was 6 in both trials. Improvements weresustained to 52 weeks in both trials. Enablement showed a statisticallysignificant difference favouring the intervention group in both trials: adjustedmean difference at 24 weeks −0.7 (95% confidence interval −1.0 to −0.4) forparents or carers and −0.9 (−1.3 to −0.6) for young people. No harms wereidentified in either group.

Conclusions

Two online interventions for self-management of eczema aimed at parents or carersof children with eczema and at young people with eczema provide a useful,sustained benefit in managing eczema severity in children and young people whenoffered in addition to usual eczema care.

Trial registration

ISRCTN registry ISRCTN79282252.

Introduction

Atopic eczema, also called atopic dermatitis, and referred to here as eczema1 is a common long term condition that can have asubstantial impact on the quality of life of both children and adults.23 Even relatively simple treatment regimens foreczema can be burdensome,4 consisting ofavoidance of triggers and irritants,56 regular emollient treatment, and use oftopical anti-inflammatory agents such as corticosteroids.

Although eczema guidelines stress the importance of education about eczema,56 international data suggest that availabilityof eczema education programmes is sparse in most countries.7 Furthermore, systematic reviews have shown limited evidence ofbenefit for educational, psychological, or self-management interventions in improvingeczema outcomes or quality of life.8910 One trial showed improved eczema outcomesafter group training for eczema involving 12 hours of face-to-face meetings with amultidisciplinary team.11 A six hour nurse lededucation programme for parents of children with eczema, evaluated in a non-randomisedstudy, showed good parental satisfaction and improved eczema from baseline,812 but 41% of the families who were referred tothe programme did not attend,8 suggestingbarriers to uptake. Implementation of such programmes is resource intensive forpatients, families, and health services.

Self-management support for long term health conditions through online interventions hasbeen shown to be associated with small but positive improvements in healthoutcomes,13 particularly theory basedinterventions that incorporate multiple behaviour change techniques.14 Despite the self-management of eczemapresenting particular challenges, there have been few rigorously developed onlineinterventions for eczema,10 and none have beenevaluated in a trial large enough to detect differences in health outcomes.151617

We evaluated two online (www.EczemaCareOnline.org.uk; video1) behavioural interventions to support self-management of eczema: one aimedat the parents or carers of children with eczema, and the other aimed at young peoplewith eczema. As parents and carers of children and young people with eczema are likelyto have different support needs, we developed two separate interventions to be evaluatedin two independent randomised controlled trials.

Methods

The Eczema Care Online trials were two separate pragmatic, multicentre, unmasked,individually randomised, superiority trials, each with two parallel groups allocated ina 1:1 ratio comparing usual care alone with an online intervention plus usual care. Onetrial recruited parents and carers of children aged 0-12 years with eczema and the otherrecruited young people aged 13-25 years with eczema. The trials were conducted withingeneral practices in the UK National Health Service. The trials included health economicand process evaluations, which will be reported separately. We have previously publishedthe protocol for the trials,18 developmentpapers detailing both interventions,1920 and a feasibility trial of a previousprototype intervention.15

As described in the published protocol paper,18a protocol amendment was made to revise the sample size in response to new informationon the minimal clinically important difference of the primary outcome measure, thePatient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM). Our original sample size used a POEM score forminimal clinically important difference of 3, which was based on research carried out insecondary care among people with moderate or severe eczema.21 Fresh evidence, however, suggested that a change in POEM scoreof 2.1 to 2.9 represents a change likely to be beyond measurement error.22 A protocol amendment was therefore made tochange the target sample size for the trials based on seeking to detect a difference inPOEM score of 2.5 points between groups, increasing the target sample size from 200 to303 for each trial.

Setting and participants

Participants were invited through a search of electronic health records and postalinvitation from participating practices around four regional centres: Wessex, West ofEngland, East Midlands, and Thames Valley and South Midlands. Potential participantswere sent an invitation pack containing an information sheet and the study URL toregister if they wished to take part. After registering, participants were asked toprovide informed consent and complete screening and baseline measures online. Forchildren younger than 16 years, the invitation was sent to their parent or carer. Inthe trial for parents and carers, informed consent and questionnaires were completedby the parent or carer. In the trial for young people, parental consent and youngpeople’s assent were sought for participants younger than 16 years, and youngpeople’s consent was sought for participants aged 16 and older. Young people aged13-25 were asked to complete their own questionnaires.

Eligibility for inclusion in the parents and carers trial included being a parent orcarer of a child aged 0-12 years, and eligibility for inclusion in the young peopletrial included being aged 13-25 years. For both trials, inclusion criteria includedchild or young individual having a general practice electronic record code for eczema(any date) and having obtained a prescription for eczema treatment (emollient,topical corticosteroid, or topical calcineurin inhibitor) in the 12 months beforeinvitation to the study. On baseline screening for both trials, potentialparticipants were included if a POEM score >5 was reported. This score thresholdwas used to include those with mild to severe eczema and to exclude those with verymild or inactive eczema to avoid floor effects.23

For both trials, potential participants were excluded if they were unable to giveinformed consent, were unable to read and write English (as the intervention contentand outcome measures were in English), had taken part in another eczema study in thepast three months, or had no internet access. Only one individual in each householdcould take part in either trial, as intervention content was similar.

Interventions

Usual care group

Participants randomised to receive usual care were recommended to use a standardinformational website,24 and theycontinued to receive usual medical advice and prescriptions from their healthcareprovider. They could seek online support but did not have access to Eczema CareOnline interventions during their participation in the trial; they were, however,given access to the intervention after the 52 week follow-up.

Intervention plus usual care group

Participants randomised to the intervention group received access to Eczema CareOnline behavioural interventions in addition to usual eczema care. Theinterventions were theory based and developed following the person based approachto intervention development,2526 and they were delivered usingLifeGuide software. The two interventions were created separately in parallel: onefor parents or carers of children with eczema and one for young people witheczema. The interventions were entirely online and self-guided and participantscould use as much or as little of the intervention as they wanted. Full details ofdevelopment and optimisation of both interventions have been publishedseparately.1920 See supplementary appendices 1 and 2for the TIDieR (template for intervention description and replication)checklists.

The interventions were co-produced by a team consisting of behaviouralpsychologists, patient representatives, clinicians (general practitioners,dermatology nurse consultants, dermatologists with expertise in eczema) andresearchers before being optimised through extensive user feedback to ensure theywere acceptable, feasible, and optimally engaging to target users. The aim of theonline interventions was to reduce eczema severity and target core behaviourslinked to eczema management: regular use of emollients, appropriate use of topicalcorticosteroids,27 avoidance of eczemairritants and triggers, minimisation of scratching, and emotional management.

All intervention content was based on evidence, or on expert consensus whenevidence was lacking. The interventions provide tailored content to suggest topicsthat may be of relevance and include interactive and audio-visual features (eg,brief eczema assessment, videos, stories, and advice from other young people andfamilies with experience of eczema). Participants are taken through a core sectioncomprising key information and behaviour change content about eczemaself-management before accessing the main menu with various topics of interest tofamilies and young people with eczema.

Outcomes

All participant reported outcome measures were collected online using LifeGuidesoftware.28 Non-responders were sentreminders by phone or SMS (up to two phone calls or up to two SMS, or both). Outcomemeasures were similar across the two trials and followed core outcome measures foreczema recommended in the Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema international coreoutcomes set for eczema.29 We did notinclude objective assessment of eczema, however, as this would have requiredface-to-face contact, which could constitute an intervention in its own right andpotentially have greater effect than the online interventions. No changes were madeto trial outcomes.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome for both trials was the difference in participant reportedeczema severity between the usual care group and intervention group, measured byPOEM every four weeks over 24 weeks.2330 POEM includes seven questions aboutthe frequency of eczema symptoms over the previous week, with a total score from 0(no eczema) to 28 (worst possible eczema). POEM can be completed by young peopleand children or by proxy (parent or carer report) and has good validity,test-retest reliability, and responsiveness to change.31 POEM is recommended for measuring the domain of eczemasymptoms in the Harmonising Outcomes for Measuring Eczema international coreoutcome set for eczema.29

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes included difference in POEM scores every four weeks over 52weeks; eczema control at 24 and 52 weeks, measured by RECAP (recap for atopiceczema patients)32; itch intensity33 at 24 and 52 weeks, measured as worstitch in the past 24 hours (not validated for proxy completion for children, andtherefore included for young people only); patient enablement at 24 and 52 weeks:the self-perceived ability to understand and cope with health problems, measuredusing the Patient Enablement Instrument34; quality of life at 24 and 52 weeks, measured by proxy using the ChildHealth Utility-Nine Dimensions (CHU-9D)35for children aged 2-12 years and using the EQ-5D-5L36 for young people aged 13-25 (quality of life was notassessed for children aged 0-2 years); and health service use and drug use,measured by review of medical notes for the three month period before baseline andthe whole 52 week trial period.

Other and process measures

At baseline, participants were asked for their prior belief about theeffectiveness of the intervention and their use of other online resources(websites or apps for eczema).

Self-reported barriers to adherence to eczema treatments were measured at 24 and52 weeks using the Problematic Experiences of Therapy Scale, and frequency ofeczema treatment use (treatment adherence) was measured by self-report at 24 and52 weeks. LifeGuide software recorded the data on intervention usage (eg, timespent on the intervention, number of logins, pages viewed) for each participantfor the duration of the 52 week trial period. A full process evaluation iscurrently in preparation; in this paper we report proportions of users meeting theminimum effective engagement threshold that we predefined for theinterventions—that is, completing the core content.3738 Health service use and drug use willbe reported separately as part of a full health economic evaluation.

Sample size

The sample size calculation was based on POEM scores every four weeks using repeatedmeasures from baseline to 24 weeks, seeking to detect a minimum clinically importantdifference of 2.5 (standard deviation 6.5) points between groups. Assuming acorrelation between repeated measures of 0.70, with 90% power and 5% significance,this would give a target sample size of 121 in each group in each of the two trials.Allowing for 20% loss to follow-up resulted in a target sample size of 303 in each ofthe two trials.

Randomisation and masking

Participants were randomised online using LifeGuide software either to usual eczemacare or to online intervention plus usual care. Randomisation was carried out inrandom permuted blocks (sizes 4 and 6) and stratified by age (children 0-5v 6-12 years; young people 13-17v 18-25 years),baseline eczema severity (POEM categories236-7 (mild), 8-16 (moderate), 17-28 (severe)), and recruitment region (four regions).It was not possible to mask participants to their allocation group, but their priorbelief in the effectiveness of the online intervention was measured at baseline tominimise potential bias. The trial management group and statisticians remainedblinded to treatment allocation during the conduct of the study and analysis.

Statistical analysis

Analysis was conducted according to a statistical analysis plan agreed in advancewith the independent trial steering committee or data monitoring committee andreported according to CONSORT (consolidated standards of reporting trials)guidelines.3940 The two trials (parents or carers, andyoung people) were analysed separately. We used descriptive statistics to comparebaseline characteristics of trial participants by allocated group. The primaryanalyses for the total POEM score used generalised linear mixed models withobservations over time from week 1 to week 24 (level 1) nested within participants(level 2). Our primary outcome is based on adjusted results, controlling for age,baseline POEM score, recruiting centre, sex, ethnicity, prior belief in theintervention, previous use of a website or app for eczema, and parental education (inthe parent and carer trial). We also report unadjusted results for the primaryoutcome.

Participants who had at least one follow-up POEM score between weeks 6 and 24 wereincluded in the primary repeated measures analysis. For all models, participants wereanalysed in the group to which they were randomised, regardless of their adherence tothat allocation (intention-to-treat analysis).

The model used all the observed data and implicitly assumes that, given the observeddata, missing POEM scores were missing at random. The model included a random effectfor centre (random intercept) and patient (random intercept and slope on time) toallow for differences between participants and between centres at baseline anddifferences between participants in the rate of change over time if a treatment-timeinteraction was statistically significant, and fixed effects for baseline covariates.We initially fitted this model (as specified in the statistical analysis plan), butas the intraclass correlation coefficient for regional centre was <0.001, regionalcentre was included as a fixed effect (rather than a random effect) in the finalmodel. An unstructured covariance matrix was used. We examined the structure andpattern of missing data, and multiple imputation was performed as a sensitivityanalysis. The imputation model included all the covariates in the analysis model, aswell as any covariates predictive of missingness. Overall, 100 imputed datasets weregenerated using multiple imputation with chained equations, and the data was analysedusing the same model as for the primary analysis.

For the analysis of secondary outcomes, we used repeated measures analysis for themonthly POEM measure up to 52 weeks consistent with that used for the primaryoutcome. For other secondary outcomes, linear regression was used for continuousoutcomes if the assumptions were met. Logistic regression was used for dichotomousoutcomes. When appropriate, we analysed highly skewed variables as dichotomousoutcomes. All secondary analyses controlled for baseline value, recruiting centre,age, sex, ethnicity, prior belief in the intervention, previous use of a website orapp for eczema, and parental education (in the parent and carer trial). The data wereanalysed using Stata version 16.

Patient and public involvement

The James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership for eczema prioritised the mosteffective form of eczema education as a key research question.41 Public contributor AR has been involved in supporting eczemamanagement for many years, including through the internet, and was involved in boththe Priority Setting Partnership and in the feasibility trial before the full scaletrial reported here. Public contributors AR, AA, and other members of the Centre ofEvidence Based Dermatology patient panel were involved from the earliest stages ofplanning the grant application and subsequently in developing trial recruitmentmaterials and interventions. AR was a member of the trial management group. Publiccontributors were involved in study interpretation and planning dissemination offindings. The independent trial steering committee included representation from keyeczema charities in the UK, also involved in planning dissemination.

Results

Participant characteristics

Recruitment took place from 2 December 2019 to 8 December 2020, with follow-upcompleted in December 2021. Recruitment was paused in April-May 2020 in response tothe covid-19 pandemic. General practitioners sent invitations to the parents orcarers of 8153 children, and 524 (6.4%) consented online to participate, of whom 340met eligibility criteria and were randomised. Invitations were sent to 5548 youngpeople (or their parent or carer if younger than 16 years), and 411 (7.4%) consentedonline to participate, of whom 337 met eligibility criteria and were randomised;three subsequently withdrew from follow-up.

At 24 weeks (primary time point), POEM was completed by 311/340 (91.5%) parents orcarers and 304/337 (90.2%) young people. At 52 weeks, POEM was completed by 303/340(89.1%) parents or carers and 283/337 (84.0%) young people (fig 1 andfig 2). Participantcharacteristics in both trials were well balanced at baseline (table 1 andtable2).

Fig 1.

Recruitment of parents or carers of children with eczema

Fig 2.

Recruitment of young people with eczema

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants in trial for parents or carers ofchildren (0-12 years) with eczema. Values are numbers (percentages) unlessstated otherwise

| Characteristics | Usualcare (n=169) | Onlineintervention plus usual care (n=171) | Total(n=340) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD)respondent’s age (years) | 37.5 (6.4) | 37.7 (6.8) | 37.6 (6.6) |

| Women | 155 (92) | 156 (91) | 311 (92) |

| Median(IQR) child’s age (years) | 4 (2-7) | 4 (2-7) | 4 (2-7) |

| Girls | 79 (47) | 85 (50) | 164 (48) |

| Respondent’s self-reported ethnic group: | |||

| White | 138 (82) | 144 (84) | 282 (83) |

| Asian | 13 (8) | 10 (6) | 23 (7) |

| Black | 7 (4) | 2 (1) | 9 (3) |

| Mixed | 6 (4) | 7 (4) | 13 (4) |

| Other | 2 (1) | 6 (4) | 8 (2) |

| Prefernot to answer | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 4 (1) |

| Highestqualification: | |||

| Degree orequivalent | 87 (53) | 80 (48) | 167 (50) |

| Diplomaor equivalent | 22 (13) | 29 (17) | 51 (15) |

| Alevel | 10 (6) | 6 (4) | 16 (5) |

| GSCE or Olevel | 14 (9) | 19 (11) | 33 (10) |

| None | 3 (2) | 5 (3) | 8 (2) |

| Other | 24 (15) | 23 (14) | 47 (14) |

| Prefernot to answer | 4 (2) | 6 (4) | 10 (3) |

| Median(IQR) prior belief in intervention score* | 7 (5-8.5) | 7 (5-8) | 7 (5-8) |

| Use ofother websites/apps for eczema in past 6 months | 31 (19) | 41 (24) | 72 (22) |

| Mean (SD)POEM score† | 12.8 (5.4) | 12.9 (5.2) | 12.8 (5.3) |

| POEMcategory: | |||

| Mild(6-7) | 25 (15) | 28 (16) | 53 (16) |

| Moderate (8-16) | 110 (65) | 102 (60) | 212 (62) |

| Severe(17-28) | 34 (20) | 41 (24) | 75 (22) |

| Median(IQR) RECAP score‡ | 11 (8-16) | 12 (9-17) | 12 (8-16) |

| Mean (SD)health related quality of life (CHU-9D) | 0.86 (0.10) | 0.87 (0.09) | 0.87 (0.10) |

CHU-9D=Child Health Utility-Nine Dimensions; IQR=interquartile range;POEM=Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure; RECAP=recap for atopic eczema patients;SD=standard deviation.

Belief that a website might be effective in helping eczema: from 1 (not atall effective) to 10 (very effective).

Measure of eczema control: from 0 (low) to 28 (high).32

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of participants in trial for young people (13-25years) with eczema. Values are numbers (percentages) unless statedotherwise

| Characteristics | Usualcare (n=169) | Onlineintervention plus usual care (n=168) | Total(n=337) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD)respondent’s age (years) | 19.0 (3.3) | 19.5 (3.5) | 19.3 (3.4) |

| Femalerespondents | 134 (79) | 125 (74) | 259 (77) |

| Respondent’s self-reported ethnic group: | |||

| White | 142 (86) | 143 (86) | 285 (86) |

| Asian | 9 (5) | 7 (4) | 16 (5) |

| Black | 2 (1) | 4 (2) | 6 (2) |

| Mixed | 10 (6) | 9 (6) | 19 (6) |

| Other | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 6 (2) |

| Prefernot to answer | - | - | - |

| Median(IQR) prior belief in intervention score* | 6 (5-8) | 6 (5-8) | 6 (5-8) |

| Use ofother websites/apps for eczema in past 6 months | 24 (14) | 26 (16) | 50 (15) |

| Mean (SD)POEM score† | 15.3 (5.5) | 15.1 (5.3) | 15.2 (5.4) |

| POEMcategory: | |||

| Mild(6-7) | 11 (7) | 10 (6) | 21 (6) |

| Moderate (8-16) | 92 (54) | 92 (55) | 184 (55) |

| Severe(17-28) | 66 (39) | 66 (39) | 132 (39) |

| Median(IQR) RECAP score‡ | 13 (8.5-17) | 13 (10-16) | 13 (9-17) |

| Median(IQR) itch intensity§ | 6 (4-7) | 6 (4-7) | 6 (4-7) |

| Mean (SD)health related quality of life (EQ-5D-5L) | 0.80 (0.18) | 0.80 (0.14) | 0.80 (0.16) |

EQ-5D-5L=five level EuroQol; IQR=interquartile range; POEM=Patient-OrientedEczema Measure; RECAP=recap for atopic eczema patients; SD=standarddeviation.

Belief that a website might be effective in helping eczema: from 1 (not atall effective) to 10 (very effective).

Measure of eczema control: from 0 (low) to 28 (high).32

Measure of itch intensity: from 1 (low) to 10 (high): “How would you rateyour itch at the worst moment during the previous 24 hours?” was includedfor young people only as not validated for use by proxy.

Primary outcome

Trial for parents and carers

Among reports from parents and carers, eczema severity showed improvement by fourweeks and appeared relatively constant over time (fig 3). Parent or carer reported mean POEM score for children over the24 week period was 10.7 in the usual care group and 9.5 in the intervention group.After adjusting for baseline POEM score, recruitment region, age, sex, ethnicity,parental education, prior belief in the intervention, and previous use of awebsite or app for eczema, the mean difference was −1.5 (95% confidence interval−2.5 to −0.6; P=0.002) between groups, showing a small but statisticallysignificant benefit in POEM scores in the intervention group (table 3). Analysis to assess proportionsachieving the minimally important clinical difference of 2.5 points was carriedout as a post-hoc analysis to aid interpretation. Overall, 39% (62) ofparticipants in the usual care group and 58% (89) in the intervention groupreported an improvement of at least 2.5 points in the POEM score at 24 weeks,giving an odds ratio of 2.1 (95% confidence interval 1.2 to 3.6) corresponding toa number needed to treat of 6 (95% confidence interval 3 to 13).

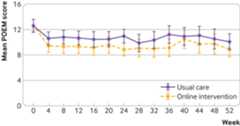

Fig 3.

Mean Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) scores for eczema severity to 52weeks in parent and carer trial

Table 3.

Primary outcome: POEM scores over 24 weeks (repeated measures analysis) intrial for parents and carers of children (0-12 years) with eczema

| Follow-up | Mean POEM score | Mean difference in score (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care (n=169) | Online intervention plus usual care (n=171) | Unadjusted | Adjusted* | Adjusted† | ||

| 24weeks | 10.7 | 9.5 | −1.1 (−2.2 to0.04) | −1.1 (−2.0 to−0.3) | −1.5 (−2.5 to−0.6)*** | |

CI=confidence interval; POEM=Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure.

Adjusted for stratification factors: baseline POEM score, recruitmentregion, and age.

Adjusted for baseline POEM score, recruitment region, age, sex,ethnicity, parental education, prior belief in the intervention, andprevious use of a website/app for eczema.

P=0.002.

Trial for young people

Among young people, the mean POEM score over 24 weeks was statisticallysignificant for the treatment-time interaction (P=0.006) showing that improvementdeveloped over several weeks. As the treatment effect varied significantly overthe first 24 weeks, scores for each time point are reported (table 4). After adjusting for baseline POEMscore, recruitment region, age, sex, ethnicity, prior belief in the intervention,and previous use of a website or app for eczema, the mean difference in POEM scoreover 24 weeks was −1.9 (95% confidence interval −3.0 to −0.8; P<0.001) betweengroups, showing a small but statistically significant benefit in POEM scores inthe intervention group (fig 4 andtable 4). Overall, 39% (63) of participantsin the usual care group and 56% (80) in the intervention group reported animprovement of at least 2.5 points in the POEM score at 24 weeks, giving an oddsratio 2.0 (95% confidence interval 1.2 to 3.5) corresponding to a number needed totreat of 6 (95% confidence interval 4 to 18).

Table 4.

Primary outcome: POEM scores over 24 weeks (repeated measures analysis) intrial for young people (13-25 years) with eczema

| Follow-up | Usual care (n=169) | Online intervention plus usual care (n=168) | Mean difference in score (95% CI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | MeanPOEM score | No | MeanPOEM score | Unadjusted | Adjusted* | Adjusted† | |||

| Week4 | 161 | 13.6 | 158 | 12.9 | −0.7 (−2.0 to0.6) | −0.6 (−1.6 to0.5) | −0.1 (−1.3 to1.0) | ||

| Week8 | 139 | 13.2 | 119 | 12.1 | −1.1 (−2.5 to0.3) | −0.9 (−2.1 to0.3) | −1.0 (−2.3 to0.4) | ||

| Week12 | 135 | 14.4 | 115 | 11.6 | −2.7 (−4.1 to−1.3) | −2.6 (−3.8 to−1.4) | −2.7 (−4.1 to−1.4) | ||

| Week16 | 122 | 14.3 | 75 | 11.2 | −3.2 (−4.7 to−1.6) | −2.9 (−4.3 to−1.5) | −3.8 (−5.4 to−2.2) | ||

| Week20 | 103 | 13.8 | 74 | 11.5 | −2.3 (−3.9 to−0.6) | −2.1 (−3.7 to−0.6) | −2.1 (−3.8 to−0.4) | ||

| Week24 | 161 | 13.9 | 143 | 11.8 | −2.1 (−3.6 to−0.5) | −1.9 (−3.3 to−0.5) | −1.7 (−3.3 to−0.1) | ||

| Over 24weeks | 13.8 | 11.9 | −2.0 (−3.2 to−0.8) | −1.8 (−2.8 to−0.9) | −1.9 (−3.0 to-0.8)*** | ||||

CI=confidence interval; POEM=Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure.

Adjusted for stratification factors: baseline POEM score, recruitmentregion, and age.

Adjusted for baseline POEM score, recruitment region, age, sex,ethnicity, prior belief in the intervention, and previous use of awebsite/app for eczema.

P<0.001.

Fig 4.

Mean Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) scores for eczema severity to 52weeks in young people trial

Sensitivity analyses using multiply imputed data for missing outcomes showedsimilar results for both interventions (see appendix tables S3 and S4).

Secondary outcomes

POEM scores over 52 weeks showed a persisting benefit for the intervention group,with adjusted mean difference in score of −1.4 (95% confidence interval −2.3 to −0.4)in the trial for parents and carers and −1.4 (−2.4 to −0.4) in the trial for youngpeople (fig 3 andfig 4). In the trial for parents and carers, 48% (74) of participants inthe usual care group and 60% (89) in the intervention group reported an improvementof at least 2.5 points in the POEM score at 52 weeks (adjusted odds ratio 1.4, 95%confidence interval 0.8 to 2.4). In the trial for young people, 47% (70) ofparticipants in the usual care group and 62% (84) in the intervention group reportedan improvement of at least 2.5 points in the POEM score at 52 weeks (adjusted oddsratio 1.6, 0.9 to 2.8).

The only significant difference between groups in secondary outcomes was in thePatient Enablement Instrument, which showed improvements of about 1 point on the 7point scale in the intervention groups in both trials by 24 weeks (table 5 andtable 6): equivalent to a difference from participants in usual care groupfeeling neutral about being helped to manage their eczema to participants in theintervention group reporting that they were now better able to understand, cope with,and manage their eczema. This difference persisted to 52 weeks in both trials (table 5 andtable 6).

Table 5.

Secondary outcomes in trial for parents and carers of children (0-12 years)with eczema. Values are mean (standard deviation) scores unless statedotherwise

| Outcome | No | Usualcare (n=169) | No | Onlineintervention plus usual care (n=171) | Mean difference (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted* | Adjusted† | |||||

| Eczemaseverity (POEM) over 52 weeks | 10.0 (6.6) | 8.9 (6.7) | −1.0 (−2.1 to0.1) | −1.1 (−1.9 to−0.3) | −1.4 (−2.3 to−0.4)*** | ||

| Eczemacontrol (RECAP)‡: | |||||||

| Week24 | 121 | 9.7 (6.3) | 116 | 9.0 (6.1) | −0.7 (−2.3 to0.9) | −1.0 (−2.4 to0.4) | −0.6 (−2.3 to1.0) |

| Week52 | 119 | 9.4 (6.9) | 117 | 8.6 (6.0) | −0.8 (−2.5 to0.9) | −0.6 (−2.1 to1.0) | −0.4 (−2.2 to1.4) |

| PatientEnablement Instrument§: | |||||||

| Week24 | 144 | 3.3 (1.4) | 135 | 2.6 (1.2) | −0.7 (−1.0 to−0.4) | −0.7 (−1.0 to−0.4) | −0.7 (−1.0 to−0.4)*** |

| Week52 | 146 | 3.4 (1.5) | 139 | 2.6 (1.3) | −0.8 (−1.1 to−0.5) | −0.8 (−1.1 to−0.5) | −0.8 (−1.2 to−0.5)*** |

| Healthrelated quality of life (CHU-9D): | |||||||

| Week24 | 126 | 0.89 (0.10) | 122 | 0.90 (0.09) | 0.01 (−0.01 to0.04) | 0.02 (−0.01 to0.04) | 0.01 (−0.02 to0.03) |

| Week52 | 122 | 0.88 (0.10) | 116 | 0.90 (0.09) | 0.02 (−0.01 to0.04) | 0.02 (−0.01 to0.04) | 0.01 (−0.02 to0.04) |

CHU-9D=Child Health Utility-Nine Dimensions; CI=confidence interval;POEM=Patient-Oriented Eczema measure; RECAP=recap for atopic eczemapatients.

Adjusted for stratification factors: baseline POEM score, recruitmentregion, and age.

Adjusted for baseline score, recruitment region, age, sex, ethnicity,parental education, prior belief in the intervention, and previous use of awebsite/app for eczema.

Measure of eczema control: scores from 0 (low) to 28 (high).32

Measures self-perceived ability to understand and cope with health problems.Instrument is scored as an average across six questions (I am able to copebetter, I am able to understand my eczema better, etc) on a scale 1=stronglyagree, 2=agree, 3=slightly agree, 4=neutral, 5=slightly disagree,6=disagree, 7=strongly disagree.

P<0.05.

Table 6.

Secondary outcomes in trial for young people (13-25 years) with eczema. Valuesare mean (standard deviation) scores unless stated otherwise

| Outcome | No | Usualcare (n=169) | No | Onlineintervention plus usual care (n=168) | Mean difference (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted* | Adjusted† | |||||

| Eczemaseverity (POEM) over 52 weeks | 12.7 (6.8) | 10.7 (6.6) | −1.7 (−2.8 to−0.5) | −1.5 (−2.4 to−0.6) | −1.4 (−2.4 to−0.4)*** | ||

| Eczemacontrol (RECAP)‡: | |||||||

| Week24 | 133 | 11.5 (6.3) | 109 | 10.3 (6.0) | −1.2 (−2.8 to−0.4) | −0.9 (−2.4 to0.5) | −0.2 (−1.6 to1.6) |

| Week52 | 130 | 10.7 (6.6) | 102 | 9.2 (6.0) | −1.5 (−3.2 to0.1) | −1.4 (−3.0 to0.2) | −1.1 (−3.0 to0.8) |

| Itchintensity | |||||||

| Week24 | 160 | 5.0 (2.5) | 139 | 5.0 (2.6) | 0.01 (−0.6 to0.6) | 0.04 (−0.5 to0.6) | 0.3 (−0.3 to0.9) |

| Week52 | 144 | 4.7 (2.7) | 130 | 4.5 (2.6) | −0.3 (−0.9 to0.4) | −0.3 (−0.9 to0.3) | −0.4 (−1.1 to−0.3) |

| PatientEnablement Instrument§: | |||||||

| Week24 | 135 | 3.7 (1.4) | 122 | 2.8 (1.1) | −0.9 (−1.2 to−0.6) | −0.9 (−1.2 to−0.6) | −0.9 (−1.3 to−0.6)*** |

| Week52 | 137 | 3.7 (1.3) | 121 | 2.7 (1.0) | −1.0 (−1.3 to−0.7) | −1.0 (−1.3 to−0.7) | −1.2 (−1.5 to−0.8)*** |

| Healthrelated quality of life (EQ5D-5L): | |||||||

| Week24 | 154 | 0.80 (0.18) | 138 | 0.80 (0.18) | 0.01 (−0.03 to0.05) | 0.01 (−0.04 to0.05) | 0.01 (−0.03 to0.05) |

| Week52 | 147 | 0.79 (0.17) | 133 | 0.83 (0.17) | 0.03 (−0.01 to0.07) | 0.03 (−0.01 to0.07) | 0.03 (−0.01 to0.08) |

EQ-5D-5L=five level EuroQol; CI=confidence interval; POEM=Patient-OrientedEczema measure; RECAP=recap for atopic eczema patients.

Adjusted for stratification factors: baseline POEM score, recruitmentregion, and age.

Adjusted for baseline score, recruitment region, age, sex, ethnicity, priorbelief in the intervention, and previous use of a website/app foreczema.

Measure of eczema control: scores from 0 (low) to 28 (high).32

Measures self-perceived ability to understand and cope with health problems.Instrument is scored as an average across six questions (I am able to copebetter, I am able to understand my eczema better, etc) on a scale 1=stronglyagree, 2=agree, 3=slightly agree, 4=neutral, 5=slightly disagree,6=disagree, 7=strongly disagree.

P<0.05.

Other outcomes did not differ between the groups, including in the ProblematicExperiences of Therapy Scale, although in the parent and carer trial the perceptionof treatments as problematic seemed to be lower in the intervention group, althoughnot statistically significant.

Treatment use was highly skewed and was therefore analysed as a dichotomous variable(7 days versus<7 days for emollient use, and any versus none fortopical corticosteroid and topical calcineurin inhibitor use). No significantdifferences were found between groups in either trial on any of the measures oftreatment use (emollient, topical corticosteroid, topical calcineurin inhibitor)measured at 24 weeks (table 7 andtable 8).

Table 7.

Treatment adherence outcomes in trial for parents and carers of children (0-12years) with eczema. Values are numbers (percentages) unless statedotherwise

| Outcome | Usualcare (n=169) | Onlineintervention plus usual care (n=171) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted* | Adjusted† | |||

| Problematic Experiences of Therapy Scale | |||||

| Week24: | |||||

| Symptomstoo severe or aggravated by treatment | 67 (45) | 52 (37) | 0.7 (0.5 to1.2) | 0.7 (0.4 to1.1) | 0.6 (0.3 to1.0) |

| Uncertainty about how to carry out treatment | 48 (32) | 40 (28) | 0.8 (0.5 to1.4) | 0.8 (0.5 to1.3) | 0.7 (0.4 to1.3) |

| Doubtsabout treatment efficacy | 71 (48) | 61 (44) | 0.8 (0.5 to1.3) | 0.8 (0.5 to1.3) | 0.6 (0.3 to1.1) |

| Practicalproblems | 77 (53) | 78 (57) | 1.2 (0.7 to1.8) | 1.1 (0.7 to1.8) | 0.9 (0.5 to1.6) |

| Week52: | |||||

| Symptomstoo severe or aggravated by treatment | 61 (42) | 54 (39) | 0.9 (0.5 to1.4) | 0.9 (0.5 to1.4) | 1.0 (0.5 to1.7) |

| Uncertainty about how to carry out treatment | 44 (31) | 40 (28) | 0.9 (0.5 to1.5) | 1.0 (0.6 to1.6) | 0.8 (0.4 to1.5) |

| Doubtsabout treatment efficacy | 67 (47) | 52 (37) | 0.7 (0.4 to1.1) | 0.6 (0.4 to1.0) | 0.5 (0.3 to0.9)*** |

| Practicalproblems | 76 (54) | 79 (57) | 1.1 (0.7 to1.8) | 1.2 (0.7 to1.9) | 0.9 (0.5 to1.5) |

| Treatment use | |||||

| Week24: | |||||

| Emollients: | |||||

| 0-6days/wk | 59 (38) | 51 (35) | - | - | |

| 7days/wk | 95 (62) | 97 (66) | 1.2 (0.7 to1.9) | 1.2 (0.7 to1.9) | 1.4 (0.7 to2.5) |

| Topical:corticosteroid or calcineurin inhibitor: | |||||

| 0days/wk | 72 (46) | 54 (36) | - | - | |

| 1-7days/wk | 83 (54) | 94 (64) | 1.5 (1.0 to2.4) | 1.6 (1.0 to2.5) | 1.5 (0.8 to2.8) |

| Week52: | |||||

| Emollients: | |||||

| 0-6days/wk | 56 (39) | 43 (30) | - | - | |

| 7days/wk | 86 (61) | 100 (70) | 1.5 (0.9 to2.5) | 1.7 (1.0 to2.8) | 2.3 (1.2 to4.5)*** |

| Topical:corticosteroid or calcineurin inhibitor: | |||||

| 0days/wk | 66 (47) | 58 (41) | - | - | |

| 1-7days/wk | 76 (54) | 84 (59) | 1.3 (0.8 to2.0) | 1.4 (0.8 to2.2) | 1.5 (0.8 to2.7) |

CI=confidence interval.

Adjusted for stratification factors: baseline POEM score, recruitmentregion, and age.

Adjusted for baseline score, recruitment region, age, sex, ethnicity,parental education, prior belief in the intervention, and previous use of awebsite/app for eczema.

P<0.05.

Table 8.

Treatment adherence outcomes in trial for young people (13-25 years) witheczema. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Outcome | Usualcare (n=169) | Onlineintervention plus usual care (n=168) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted* | Adjusted† | |||

| Problematic Experiences of Therapy Scale | |||||

| Week24: | |||||

| Symptomstoo severe or aggravated by treatment | 85 (56) | 76 (57) | 1.0 (0.6 to1.6) | 1.0 (0.6 to1.7) | 1.0 (0.6 to1.9) |

| Uncertainty about how to carry out treatment | 63 (42) | 54 (40) | 1.0 (0.6 to1.5) | 0.9 (0.6 to1.5) | 1.1 (0.6 to2.0) |

| Doubtsabout treatment efficacy | 103 (68) | 89 (67) | 1.0 (0.6 to1.6) | 1.0 (0.6 to1.6) | 1.1 (0.6 to2.1) |

| Practicalproblems | 116 (78) | 104 (79) | 1.0 (0.6 to1.8) | 1.0 (0.6 to1.8) | 1.1 (0.5 to2.3) |

| Week52: | |||||

| Symptomstoo severe or aggravated by treatment | 80 (55) | 71 (55) | 1.0 (0.6 to1.6) | 1.0 (0.6 to1.6) | 1.1 (0.6 to2.0) |

| Uncertainty about how to carry out treatment | 58 (40) | 57 (44) | 1.2 (0.7 to1.9) | 1.2 (0.7 to1.9) | 1.5 (0.8 to2.7) |

| Doubtsabout treatment efficacy | 88 (63) | 80 (62) | 1.0 (0.6 to1.6) | 1.0 (0.6 to1.6) | 0.9 (0.5 to1.7) |

| Practicalproblems | 116 (81) | 111 (85) | 1.4 (0.8 to2.7) | 1.5 (0.8 to2.8) | 1.4 (0.6 to3.1) |

| Treatment use | |||||

| Week24: | |||||

| Emollient: | |||||

| 0-6days/wk | 71 (44) | 64 (46) | - | - | |

| 7days/wk | 89 (56) | 74 (54) | 0.9 (0.6 to1.5) | 0.9 (0.6 to1.5) | 1.2 (0.7 to2.2) |

| Topical:corticosteroid or calcineurin inhibitor: | |||||

| 0days/wk | 61 (38) | 55 (40) | - | - | |

| 1-7days/wk | 98 (62) | 83 (60) | 0.9 (0.6 to1.6) | 0.9 (0.6 to1.5) | 1.0 (0.5 to1.8) |

| Week52: | |||||

| Emollient: | |||||

| 0-6day/wk | 66 (46) | 60 (46) | - | - | |

| 7days/wk | 79 (55) | 72 (55) | 1.0 (0.6 to1.6) | 1.0 (0.6 to1.6) | 0.9 (0.5 to1.8) |

| Topical:corticosteroid or calcineurin inhibitor: | |||||

| 0days/wk | 51 (35) | 48 (36) | - | - | |

| 1-7days/wk | 93 (65) | 84 (64) | 1.0 (0.6 to1.6) | 0.9 (0.6 to1.5) | 0.9 (0.5 to1.7) |

CI=confidence interval.

Adjusted for stratification factors: baseline POEM score, recruitmentregion, and age.

Adjusted for baseline score, recruitment region, age, sex, ethnicity, priorbelief in the intervention, and previous use of a website/app foreczema.

Analysis of completion of core content (predefined minimum effective engagementthreshold) was excellent: data for online intervention usage showed that mostparticipants had completed the core module by 24 weeks: 299/340 (88%) parents andcarers and 310/337 (92%) young people.

Subgroup analyses

Prespecified subgroup analyses in both trials showed that participants allocated tothe intervention group showed similar benefit in eczema outcomes, regardless of age,sex, eczema severity, baseline treatment use, prior belief in effectiveness ofintervention, or previous use of other eczema related websites (see appendix tablesS5 and S6). No harms or unintended effects were identified in either trial.

Discussion

This study found that two brief online behavioural interventions to enableself-management of eczema for parents and carers of children with eczema and for youngpeople with eczema provided a useful benefit in eczema severity at 24 weeks, which wassustained at 52 weeks. A number needed to treat of 6 compares favourably with many drugtreatments and is particularly important in the absence of identifiable harms and in thecontext of a low cost and highly scalable intervention.

Use of eczema treatments did not differ between groups, but scores on the PatientEnablement Instrument differed significantly. We therefore believe that the impact ofthe interventions may have been through enabling parents and carers of children witheczema and young people with eczema to feel more confident in coping with the condition.The process evaluation will be reported separately and will provide insights into themechanism of action of the interventions.

The Eczema Care Online toolkits were offered to the intervention group in addition tousual eczema care. The toolkits therefore should be viewed as supplementing rather thanreplacing health professional support.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The two Eczema Care Online trials have several strengths, including long follow-up,high rates of follow-up, broad inclusion criteria and range of eczema severities, andoutcome measures of importance to young people with eczema and carers, leadingoverall to a pragmatic trial and generalisable results.

It was not possible to blind participants to treatment allocation, and this couldhave led to bias in the primary outcome, despite measures to adjust for prior beliefin the intervention to minimise this potential bias in analysis. However, even if acontextual effect (or placebo effect) contributes to improvement in eczema, theeffect is still a valuable benefit to people with eczema and their families,particularly when it improves their ability to cope with the condition.

The improvements in primary outcome (1.5 (95% confidence interval 0.6 to 2.5) forchildren and 1.9 (0.8 to 3.0) for young people) were less than the target of 2.5points on the POEM score. The most recent research on the minimal clinicallyimportant difference for POEM suggests that a range of 2.1 to 2.9 represents a smallchange that is likely to be beyond measurement error, and that a “small improvementin many individuals could result in a large reduction in burden at a societallevel.”22 Our estimates fall below thisbut with narrow confidence intervals that exclude the null hypothesis and include theminimal clinically important difference. However, substantial proportions ofparticipants experienced clinically important improvement: more than half in theintervention group in both trials achieved an improvement at or above the minimalclinically important difference, and the number needed to treat for one participantto benefit compared with usual care was 6 in both trials, which is noteworthy forsuch a low cost intervention.

Recruitment into this trial was through a search of general practice records andpostal invitations to potentially eligible participants. Although this method forrecruitment resulted in a low response rate, it is consistent with other similarstudies,42 which means that theinvitation to participate will not always be salient to people because eczema is arelapsing-remitting condition and people are unlikely to respond when in remission.In real world use, the interventions are envisaged as being particularly appropriatearound newly diagnosed eczema or flare-ups, where uptake is likely to be higher andthe intervention could potentially be most effective.

Some of the recruitment and follow-up of participants in this study took place duringthe covid-19 pandemic. Qualitative research carried out during the trial suggestedthat this could have had both positive and negative impacts on participants’eczema.43 For example, it may have madeit harder for participants to access healthcare for some months during the study andto discuss or change their treatments in response to the intervention, although thislack of access may have improved engagement with the online toolkits.

Comparison with other studies

Few fully powered trials have been carried out of self-management or educationalinterventions for eczema, and those that have been published used different outcomemeasures, making direct comparisons challenging. However, much more costlyeducational interventions have only shown modest improvements in eczema, and webelieve the effect size in our trials compares favourably with more intensiveinterventions.

In some contexts, the effectiveness of online interventions has been shown to beenhanced by health professional support, and this was tested in a feasibility studybefore this trial.15 In the three armfeasibility study, 143 parents or carers of children with eczema were randomised to:usual care alone; an online intervention plus usual care; or an online interventionplus 20 minutes of health professional support (primarily practice nurses) and usualcare. In the feasibility study, health professional support did not lead to betteroutcomes, and process evaluation indicated that the health professional support wasnot highly valued by participants in this context, and it was therefore not includedin the full scale trial reported here.

Implications for practice and future research

As 90% of people with eczema are managed in primary care in the UK, further researchis needed to explore the impact of online interventions in healthcare settings wheresecondary care management is more common or where patient support for eczema is moreextensive. Although some aspects of the Eczema Care Online interventions are specificto the UK, such as available treatments and support for navigating health services,the intervention could readily be adapted to other settings.

Conclusions

Eczema Care Online interventions for parents and carers of children with eczema andfor young people with eczema are evidence based resources that have been shown tohelp young people better understand, cope with, and manage their eczema, and offer auseful benefit in clinical outcomes, sustained over 52 weeks. A small amount ofbenefit at low cost with no identifiable harms for a condition that affects a largenumber of people can lead to substantial health benefit for the public in absoluteterms. The findings reinforce the key role of health professionals in signpostingpatients and carers towards self-management support for long term conditions.

What is already known on this topic

People with eczema and their families often report they have been giveninsufficient or conflicting information about the condition or how tomanage it

Group education delivered by multidisciplinary teams has been shown toimprove eczema outcomes but is expensive and time consuming todeliver

The effectiveness of online self-management support for eczema has notbeen assessed in adequately powered trials

What this study adds

Online interventions providing evidence based support for eczemaself-management led to a useful, sustained benefit in eczema severityover six and 12 months in children and young people

This small but meaningful improvement is particularly valuable given thelow cost and high scalability of the online support and absence ofidentifiable harms

Acknowledgments

These trials have contributed to reducing the carbon footprint of clinical trials. Byrecruiting participants and delivering the trial interventions entirely online wereduced the paperwork and storage involved in data collection and eliminated travel forstudy visits.

We thank all patient and public involvement contributors, participants, families,practices, the National Institute for Health and Care Research Clinical ResearchNetwork, National Eczema Society, Eczema Outreach Support, and members of the ProgrammeSteering Committee for their support.

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Supplementary information: additional material and a video discussing the studyfindings

Contributors: MSa and KST conceived the study and initial study design incollaboration with IM, LY, PLi, HCW, JRC, MJR, SaL, BS, GG, TS, SiL, AR, and AA,with later input from JN, JH, SW, MSt, KG, KS, and TB. Specific advice was givenby BS and TB on trial design and medical statistics; IM, LY, KG, KS, PLe, and LHon the process evaluation; and TS on the health economic evaluation. TB and BSconducted the analyses. All the authors contributed to the drafting of this paper,led by MS, and approved the final manuscript. MSa is guarantor. The correspondingauthor attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no othersmeeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: This study presents independent research funded by the National Institutefor Health and Care Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for AppliedResearch programme (RP-PG-0216-20007). The funders had no role in the collection,analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit thearticle for publication. Eczema Care Online interventions were developed usingLifeGuide software, which was partly funded by the NIHR Southampton BiomedicalResearch Centre. SiL was supported by a Wellcome senior research fellowship inclinical science (205039/Z/16/Z). The views expressed are those of the authors andnot necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR, or the Departmentof Health and Social Care. The University of Southampton was the research sponsorfor this trial.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure formatwww.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/ and declare: no support fromany organisation other than the National Institute for Health and Care Researchfor the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations thatmight have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; and noother relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced thesubmitted work, other than LH has received consultancy fees from the University ofOxford on an educational grant funded by Pfizer, unrelated to the submittedwork.

The lead author (MSa) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, andtransparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of thestudy have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as originallyplanned and registered have been explained.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: We haveshared our findings with relevant advocacy groups, participants in the trial,their families, and the practices involved. Blogs, a Twitter account, and plainEnglish summaries of papers of related research can be viewed athttps://www.nottingham.ac.uk/eco/.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Ethical approval

The trials were approved by South Central-Oxford A Research Ethics Committee(19/SC/0351).

Data availability statement

Consent was not obtained from participants for data sharing. Authors will considerreasonable request to make relevant anonymised participant level data available.

References

- 1.Johansson SG, Bieber T, Dahl R, et al. Revised nomenclature for allergy for global use:Report of the Nomenclature Review Committee of the World Allergy Organization,October 2003. J Allergy Clin Immunol2004;113:832-6. 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.12.591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC, et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: ananalysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions.J Invest Dermatol2014;134:1527-34. 10.1038/jid.2013.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abuabara K, Yu AM, Okhovat JP, Allen IE, Langan SM. The prevalence of atopic dermatitis beyond childhood:A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies.Allergy2018;73:696-704. 10.1111/all.13320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arents BWM. Eczema treatment: it takes time to do noharm. Br J Dermatol2017;177:613-4. 10.1111/bjd.15788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sidbury R, Tom WL, Bergman JN, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopicdermatitis: Section 4. Prevention of disease flares and use of adjunctivetherapies and approaches. J Am Acad Dermatol2014;71:1218-33. 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.08.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institute for Health and CareExcellence. Atopic eczema in under 12s: diagnosis and management Clinical Guideline.[GC57.]https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG57/chapter/1-Guidance#education-and-adherence-to-therapy-2accessed 14 April 2022. [PubMed]

- 7.Global Patient Initiative to Improve Eczema Care.https://www.improveeczemacare.com/dashboard accessed 14 April2022.

- 8.Ersser SJ, Cowdell F, Latter S, et al. Psychological and educational interventions foratopic eczema in children. Cochrane Database SystRev2014;(1):CD004054. 10.1002/14651858.CD004054.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pickett K, Loveman E, Kalita N, Frampton GK, Jones J. Educational interventions to improve quality of lifein people with chronic inflammatory skin diseases: systematic reviews of clinicaleffectiveness and cost-effectiveness. Health TechnolAssess2015;19:1-176, v-vi.10.3310/hta19860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ridd MJ, King AJL, Le Roux E, Waldecker A, Huntley AL. Systematic review of self-management interventionsfor people with eczema. Br J Dermatol2017;177:719-34. 10.1111/bjd.15601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Staab D, von Rueden U, Kehrt R, et al. Evaluation of a parental training program for themanagement of childhood atopic dermatitis. Pediatr AllergyImmunol2002;13:84-90. 10.1034/j.1399-3038.2002.01005.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jackson K, Ersser SJ, Dennis H, Farasat H, More A. The Eczema Education Programme: interventiondevelopment and model feasibility. J Eur Acad DermatolVenereol2014;28:949-56. 10.1111/jdv.12221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panagioti M, Richardson G, Small N, et al. Self-management support interventions to reducehealth care utilisation without compromising outcomes: a systematic review andmeta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res2014;14:356. 10.1186/1472-6963-14-356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Webb TL, Joseph J, Yardley L, Michie S. Using the internet to promote health behavior change:a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use ofbehavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy.J Med Internet Res2010;12:e4. 10.2196/jmir.1376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santer M, Muller I, Yardley L, et al. Supporting self-care for families of children witheczema with a Web-based intervention plus health care professional support: pilotrandomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res2014;16:e70. 10.2196/jmir.3035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bergmo TS, Wangberg SC, Schopf TR, Solvoll T. Web-based consultations for parents of children withatopic dermatitis: results of a randomized controlled trial.Acta Paediatr2009;98:316-20. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.01033.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Os-Medendorp H, Koffijberg H, Eland-de Kok PC, et al. E-health in caring for patients with atopicdermatitis: a randomized controlled cost-effectiveness study of internet-guidedmonitoring and online self-management training. Br JDermatol2012;166:1060-8. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10829.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muller I, Stuart B, Sach T, et al. Supporting self-care for eczema: protocol for tworandomised controlled trials of ECO (Eczema Care Online) interventions for youngpeople and parents/carers. BMJ Open2021;11:e045583. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sivyer K, Teasdale E, Greenwell K, et al. Supporting families managing childhood eczema:developing and optimising eczema care online using qualitativeresearch. Br J Gen Pract2022;72:e378-89. 10.3399/BJGP.2021.0503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenwell K, Ghio D, Sivyer K, et al. Eczema Care Online: development and qualitativeoptimisation of an online behavioural intervention to support self-management inyoung people with eczema. BMJ Open2022;12:e056867. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schram ME, Spuls PI, Leeflang MM, Lindeboom R, Bos JD, Schmitt J. EASI, (objective) SCORAD and POEM for atopic eczema:responsiveness and minimal clinically important difference.Allergy2012;67:99-106. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02719.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Howells L, Ratib S, Chalmers JR, Bradshaw L, Thomas KS, CLOTHES trial team . How should minimally important change scores for thePatient-Oriented Eczema Measure be interpreted? A validation using variedmethods. Br J Dermatol2018;178:1135-42. 10.1111/bjd.16367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charman CR, Venn AJ, Ravenscroft JC, Williams HC. Translating Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM)scores into clinical practice by suggesting severity strata derived usinganchor-based methods. Br J Dermatol2013;169:1326-32. 10.1111/bjd.12590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Eczema Society.https://eczema.org/ accessed 25 May 2022.

- 25.Yardley L, Morrison L, Bradbury K, Muller I. The person-based approach to interventiondevelopment: application to digital health-related behavior changeinterventions. J Med Internet Res2015;17:e30. 10.2196/jmir.4055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morrison L, Muller I, Yardley L, et al. The person-based approach to planning, optimising,evaluating and implementing behavioural health interventions.Eur Health Psychol2018;20:464-9. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lax SJ, Harvey J, Axon E, et al. Strategies for using topical corticosteroids inchildren and adults with eczema. Cochrane Database SystRev2022;3:CD013356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams S, Yardley L, Weal M, et al. Introduction to LifeGuide: Open-source Software for CreatingOnline Interventions for Health Care.Health Promotion and Training,2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams HC, Schmitt J, Thomas KS, et al. HOME Initiative . The HOME Core outcome set for clinical trials ofatopic dermatitis[published Online First: 2022/03/31]. J Allergy ClinImmunol2022;149:1899-911.10.1016/j.jaci.2022.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Charman CR, Venn AJ, Williams HC. The patient-oriented eczema measure: development andinitial validation of a new tool for measuring atopic eczema severity from thepatients’ perspective. Arch Dermatol2004;140:1513-9. 10.1001/archderm.140.12.1513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmitt J, Langan S, Deckert S, et al. Harmonising Outcome Measures for Atopic Dermatitis (HOME)Initiative . Assessment of clinical signs of atopic dermatitis: asystematic review and recommendation. J Allergy ClinImmunol2013;132:1337-47. 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Howells LM, Chalmers JR, Gran S, et al. Development and initial testing of a new instrumentto measure the experience of eczema control in adults and children: Recap ofatopic eczema (RECAP). Br J Dermatol2020;183:524-36. 10.1111/bjd.18780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yosipovitch G, Reaney M, Mastey V, et al. Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale: psychometricvalidation and responder definition for assessing itch in moderate-to-severeatopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol2019;181:761-9. 10.1111/bjd.17744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howie JG, Heaney DJ, Maxwell M, Walker JJ. A comparison of a Patient Enablement Instrument (PEI)against two established satisfaction scales as an outcome measure of primary careconsultations. Fam Pract1998;15:165-71. 10.1093/fampra/15.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stevens K. Valuation of the Child Health Utility 9DIndex. Pharmacoeconomics2012;30:729-47. 10.2165/11599120-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the newfive-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual LifeRes2011;20:1727-36. 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yardley L, Spring BJ, Riper H, et al. Understanding and promoting effective engagement withdigital behavior change interventions. Am J PrevMed2016;51:833-42. 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller S, Ainsworth B, Yardley L, et al. A framework for analyzing and measuring usage andengagement data (AMUsED) in digital interventions. J MedInternet Res2019;21:e10966. 10.2196/10966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boutron I, Altman DG, Moher D, Schulz KF, Ravaud P, CONSORT NPT Group . CONSORT Statement for Randomized Trials ofNonpharmacologic Treatments: A 2017 Update and a CONSORT Extension forNonpharmacologic Trial Abstracts. Ann Intern Med2017;167:40-7. 10.7326/M17-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, CONSORT Group . CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines forreporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ2010;340:c332. 10.1136/bmj.c332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Batchelor JM, Ridd MJ, Clarke T, et al. The Eczema Priority Setting Partnership: acollaboration between patients, carers, clinicians and researchers to identify andprioritize important research questions for the treatment ofeczema. Br J Dermatol2013;168:577-82. 10.1111/bjd.12040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Santer M, Ridd MJ, Francis NA, et al. Emollient bath additives for the treatment ofchildhood eczema (BATHE): multicentre pragmatic parallel group randomisedcontrolled trial of clinical and cost effectiveness.BMJ2018;361:k1332. 10.1136/bmj.k1332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steele M, Howells L, Santer M, et al. How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected eczemaself-management and help seeking? A qualitative interview study with young peopleand parents/carers of children with eczema. Skin HealthDis2021;1:e59. 10.1002/ski2.59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information: additional material and a video discussing the studyfindings

Data Availability Statement

Consent was not obtained from participants for data sharing. Authors will considerreasonable request to make relevant anonymised participant level data available.