Oxygen as Acceptor

Vitaliy B Borisov

Michael I Verkhovsky

Address correspondence to Vitaliy B. Borisov,bor@genebee.msu.su

Received 2015 Aug 19; Revision requested 2015 Sep 14; Collection date 2015 Dec.

Abstract

Like most bacteria,Escherichia coli has a flexible and branched respiratory chain that enables the prokaryote to live under a variety of environmental conditions, from highly aerobic to completely anaerobic. In general, the bacterial respiratory chain is composed of dehydrogenases, a quinone pool, and reductases. Substrate-specific dehydrogenases transfer reducing equivalents from various donor substrates (NADH, succinate, glycerophosphate, formate, hydrogen, pyruvate, and lactate) to a quinone pool (menaquinone, ubiquinone, and dimethylmenoquinone). Then electrons from reduced quinones (quinols) are transferred by terminal reductases to different electron acceptors. Under aerobic growth conditions, the terminal electron acceptor is molecular oxygen. A transfer of electrons from quinol to O2 is served by two major oxidoreductases (oxidases), cytochromebo3 encoded bycyoABCDE and cytochromebd encoded bycydABX. Terminal oxidases of aerobic respiratory chains of bacteria, which use O2 as the final electron acceptor, can oxidize one of two alternative electron donors, either cytochromec or quinol. This review compares the effects of different inhibitors on the respiratory activities of cytochromebo3 and cytochromebd inE. coli. It also presents a discussion on the genetics and the prosthetic groups of cytochromebo3 and cytochromebd. TheE. coli membrane contains three types of quinones that all have an octaprenyl side chain (C40). It has been proposed that thebo3 oxidase can have two ubiquinone-binding sites with different affinities.

“What’s new” in the revised article: The revised article comprises additional information about subunit composition of cytochromebd and its role in bacterial resistance to nitrosative and oxidative stresses. Also, we present the novel data on the electrogenic function ofappBCX-encoded cytochromebd-II, a secondbd-type oxidase that had been thought not to contribute to generation of a proton motive force inE. coli, although its spectral properties closely resemble those ofcydABX-encoded cytochromebd.

TWO TYPES OF METABOLISM, TWO TYPES OF OXIDASES

Anaerobiosis versus Aerobiosis inEscherichia coli

Like most bacteria,Escherichia coli has a flexible and branched respiratory chain that enables the prokaryote to live under a variety of environmental conditions, from highly aerobic to completely anaerobic.E. coli induces the expression of those respiratory components that are best suited to a particular environment. In general, the bacterial respiratory chain is composed of dehydrogenases, a quinone pool, and reductases. Substrate-specific dehydrogenases transfer reducing equivalents from various donor substrates (NADH, succinate,α-glycerophosphate, formate, hydrogen, pyruvate, and lactate) to a quinone pool (menaquinone, ubiquinone, and dimethylmenoquinone). Then electrons from reduced quinones (quinols) are transferred by terminal reductases to different electron acceptors. Under aerobic growth conditions, the terminal electron acceptor is molecular oxygen. A transfer of electrons from quinol to O2 is served by two major oxidoreductases (oxidases), cytochromebo3 and cytochromebd (it is worth noting that accumulated evidence over the past few years also suggests the contribution of a secondbd-type oxidase, cytochromebd-II, to the electron transfer and membrane potential generation). When oxygen is not available (under anaerobic conditions), alternative terminal electron acceptors, including nitrate, nitrite, dimethyl sulfoxide, trimethylamineN-oxide, and fumarate, can be used, and the reaction is catalyzed by nitrate reductases, nitrite reductase, dimethyl sulfoxide reductases, trimethylamineN-oxide reductase, and fumarate reductase, respectively (reviewed in references1 and2).

Two Types of Quinol Oxidases Only

Terminal oxidases of aerobic respiratory chains of bacteria, which use O2 as the final electron acceptor, can oxidize one of two alternative electron donors, either cytochromec or quinol. Oxidases utilizing cytochromec are called cytochromec oxidases, whereas oxidases oxidizing quinol are referred to as quinol oxidases (3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13). Cytochromec oxidases cannot directly accept reducing equivalents from quinol. For this purpose, there is an additional, middle component of the respiratory chain between dehydrogenase and oxidase, the cytochromebc1 complex, which enables the transfer of electrons from quinol to cytochromec. Respiratory chains of many aerobic bacteria, such asParacoccus denitrificans andAzotobacter vinelandii, contain thebc1 complex and both types of terminal oxidase, cytochromec and quinol oxidases. For instance,P. denitrificans has one quinol oxidase (ba3) and two cytochromec oxidases (aa3 andcbb3) (14,15).A. vinelandii has two quinol oxidases (bo3 andbd) and one cytochromec oxidase (cbb3) (reviewed in references16 and17). As shown inFig. 1, the aerobic respiratory chain ofE. coli is much simpler than those ofP. denitrificans andA. vinelandii. It lacks the cytochromebc1 complex and any cytochromec oxidase but contains instead three quinol oxidases,bo3,bd, andbd-II (reviewed in references17,18,19,20, and21).

Figure 1.

Simplified view of theE. coli respiratory chain under aerobic and microaerobic conditions. The two NADH-quinone oxidoreductases called NDH-I and NDH-II and succinate-quinone oxidoreductase (SQR) transfer reducing equivalents to ubiquinone-8 (UQ-8) to yield reduced UQ-8, ubiquinol-8. Three quinol-oxygen oxidoreductases, cytochromebo3 (CyoABCD), cytochromebd (CydABX), and cytochromebd-II (AppBCX), oxidize ubiquinol-8 and reduce O2 to 2H2O. CydABX and possibly AppBCX oxidize menaquinol-8. NDH-I, CyoABCD, CydABX, and AppBCX are coupled (ΔμH+ generators); NDH-II and SQR are uncoupled (no ΔμH+ generation). The energetic efficiency of each enzyme is indicated as the number of protons delivered to the periplasmic side of the membrane per electron (H+/e− ratio).doi:10.1128/ecosalplus.ESP-0012-2015.f1

Physiological Functions

Cytochromebo3 predominates under high aeration, whereas cytochromebd is expressed under low oxygen tension (22,23,24) (Table 1). It is of interest that the cytochromebo3 level increases about 150-fold during aerobic growth, but the cytochromebd level falls only 3-fold, i.e., the change in the cytochromebd level in response to oxygen is much smaller than that of the cytochromebo3 level (23). Both oxidases catalyze the oxidation of ubiquinol-8 to allow cellular respiration with oxygen as the terminal electron acceptor (25). Cytochromebd can also oxidize menaquinol-8 (26,27), which replaces ubiquinol-8 upon a change of growth conditions from aerobic to anaerobic (2).

Table 1.

Properties of cytochromebo3 and cytochromebd inE. coli

| Property | Cytochromebo3 | Cytochromebd |

|---|---|---|

| Level of O2 tension for expressiona | High | Low |

| Catalyzed reaction of oxidationb | Ubiquinol-8 → ubiquinone-8 | Ubi(mena)quinol-8 → ubi(mena)quinone-8 |

| Catalyzed reaction of reductionb | O2 → 2H2O | O2 → 2H2O |

| Energetic efficiency (H+/e− ratio)c | 2 (true proton pump) | 1 |

| KD (O2) (μM)d | >300 | 0.28 |

| ApparentKm for O2 (μM)e | 0.016–2.9 | 0.003–2 |

| ApparentKm for nonphysiological reductants (mM):f | ||

| Ubiquinol-1 | 0.05 | 0.23 |

| Menadiol | 38 | 1.67 |

| TMPD (N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine) | 9.5 | 18.2 |

| Operon encoding oxidaseg | cyoABCDE | cydABX |

| Subunits (mass [kDa])h | CyoA (33.5) | CydA (57) |

| CyoB (75) | CydB (43) | |

| CyoC (20.5) | CydX (4) | |

| CyoD (12) | ||

| Redox cofactors (Em value[s] [mV])i | Hemeb (+180, +280) | Hemeb558 (+176) |

| Hemeo3 (+180, +280) | Hemeb595 (+168) | |

| CuB (+370) | Hemed (+258) |

Both cytochromebo3 and cytochromebd are primary generators of a transmembrane gradient of electrochemical H+ potentials (ΔμH+), because the reaction arising from the transfer of reducing equivalents from quinol to O2 is coupled directly to transmembrane charge separation (28,29,32,50,51,52,53,54). The energy conserved in the form of ΔμH+ can be used by theE. coli cell for ATP synthesis, the transport of nutrients, and other useful work. Thus, the main function of both oxidases is energy conservation. The two enzymes, however, are different in their bioenergetic efficiencies (transmembrane proton translocation ratios, or the number of protons delivered to the periplasmic side of the membrane per electron [H+/e− ratios]), with an H+/e− ratio of 2 for cytochromebo3 and an H+/e− ratio of 1 for cytochromebd (28,29) (Table 1). This difference is because cytochromebo3 is a true proton pump, whereas cytochromebd is not capable of proton pumping (28,29). As sources of oxidizing power, cytochromebo3 and cytochromebd can support disulfide bond formation upon protein folding catalyzed by the DsbA-DsbB system (55).

Apart from energy conservation, cytochromebd endowsE. coli with a number of specific physiological functions. Cytochromebd can serve as an oxygen scavenger and inhibit the degradation of O2-sensitive enzymes present under anaerobic and microaerophilic conditions (56). In a recent systematic mutational analysis to elucidate the contribution of the respiratory pathways to the abilities of commensal and pathogenic (enterohemorrhagic)E. coli strains to colonize a streptomycin-treated mouse intestine, mutants lacking cytochromebd failed to colonize whereas cytochromebo3 was found not to be necessary for colonization (57).

The cytochromebd contents increase not only at low oxygen concentrations, but also under some unfavorable conditions, such as alkaline pH (58), high temperature (59,60), the presence of uncouplers-protonophores (58,61,62), and low concentrations of cyanide (63) in growth media. Mutants defective in cytochromebd are sensitive to H2O2 (60) and a self-produced extracellular factor that inhibits their growth (64,65). Mutants that cannot synthesize cytochromebd are also unable to exit from the stationary phase and resume aerobic growth at 37°C (66,67). The expression of cytochromebd, instead of cytochromebo3, may enhance bacterial tolerance to oxidative and nitrosative stresses (68,69,70,71). In particular, cytochromebd contributes to bacterial resistance to peroxynitrite (71,72), nitric oxide (68,69,70,71,73,74,75,76,77), carbon monoxide (78,79), and hydrogen peroxide (59,70,71,80,81,82,83,84,85,86).

Inhibitors

Table 2 compares the effects of different inhibitors on the respiratory activities of cytochromebo3 and cytochromebd inE. coli. Inhibitors of the quinol oxidases can be divided into two groups: quinol-like compounds acting at a quinol-binding site(s) and heme ligands (e.g., cyanide, azide, and NO) acting at the oxygen-binding/reducing site. A specific feature of cytochromebd is that it is much less sensitive to cyanide and azide than cytochromebo3 (32) (Table 2). The lower sensitivity of cytochromebd to anionic heme ligands may be a result of an elevated electron density on the central ion of iron due to the breaking of the circle conjugate π-electron structure in thed-type porphyrin ring and/or may point to a more hydrophobic environment for the O2-reducing site of cytochromebd than for that of cytochromebo3. It is of interest that the quinolone-type compound aurachin D and its derivatives in submicromolar concentrations specifically inhibit cytochromebd but virtually do not affect cytochromebo3 (87). These outcomes may indicate some differences in the specific structures of quinol-binding sites in cytochromebo3 and cytochromebd. It has been shown recently that cytochromebd inE. coli is a bacterial membrane target for a cationic cyclic decapeptide, gramicidin S (50% inhibitory concentration, ∼5.3μM) (Table 2), although it has been generally accepted that the main target of gramicidin S is the membrane lipid bilayer rather than the protein components (88). This finding can provide new insight for the molecular design and development of novel gramicidin S-based antibiotics. The effect of gramicidin S on cytochromebd and some other membrane-bound proteins may be the alteration of the protein structure through binding to the hydrophobic protein surface (88).

Table 2.

Effects of inhibitors on quinol oxidase activities of cytochromebo3 and cytochromebd inE. coli

| Inhibitora | Concentration, inhibition for: | |

|---|---|---|

| Cytochromebo3 | Cytochromebd | |

| KCN | 10μM | 2 mM |

| NaN3 | 15 mM | 400 mM |

| H2O2 | 300 mM | 120 mM |

| HOQNO (2-n-heptyl-4-hydroxyquinolineN-oxide) | 2μM | 7μM |

| ZnSO4 | 1μM | 60μM |

| Piericidin A | 2μM | 15μM |

| Antimicin A | 50μM, 18% | 50μM, 80% |

| UHDBT (undecylhydroxydioxobenzothiazole) | 20μM, 97% | 20μM, 18% |

| (1,5-Dimethylhexyl)quinazolinamide | 100μM, 23% | 100μM, 88% |

| (1-Methyldecyl)quinazolinamide | 100μM, 24% | 100μM, 85% |

| Stigmatellin | 200μM, 94% | 200μM, 14% |

| Nigericin | 100μM, 35% | 100μM, 44% |

| Dibromothymoquinone | 100μM, 82% | 100μM, 38% |

| Aurachin A | 700μM, 56% | 700μM, 27% |

| Aurachin C | 214 nM, 90% | 214 nM, 90% |

| Aurachin D | 400 nM, 5% | 400 nM, 93% |

| NO | << 10−8 M | 100 nM |

| PCP | 200μM | |

| TTFA | 1 mM, 35% | |

| Gramicidin S | 189μM | 5.3μM |

The concentrations shown for KCN, NaN3, H2O2, HOQNO, ZnSO4, and piericidin A (32) and gramicidin S (88) are the concentrations required for 50% inhibition of the ubiquinol-1 oxidase activities of the purified cytochromesbo3 andbd. For PCP (pentachlorophenol) and NO (nitric oxide), the inhibition constants (Ki values) are shown (73,89). For TTFA (2-thenoyl trifluoroacetone), the data shown are the concentrations yielding the indicated percent inhibition of the ubiquinol-1 oxidase activity of purified cytochromebd (47). For other inhibitors, the data shown are the concentrations yielding the indicated percent inhibition of the duroquinol oxidase activities of the membranes containing either cytochromebo3 or cytochromebd (87).

GENETICS

Oxidase Encoding

Cytochromebo3

Cytochromebo3 is composed of four different subunits (90,91,92) encoded by thecyoABCDE operon (39,45) (Table 1). ThecyoABCDE operon, located at 10.2 min on theE. coli genetic map (39,93), has been cloned and sequenced (44). Subunits I (75 kDa), II (33.5 kDa), and III (20.5 kDa) of cytochromebo3 appeared to be homologous to the counterparts of the eukaryotic and prokaryoticaa3-type cytochromec oxidases (45) and were referred to ascyoB,cyoA, andcyoC gene products, respectively, as determined by protein sequencing (46) and other approaches (44,94,95). Thus, cytochromebo3 is a member of the heme-copper terminal oxidase superfamily (45,96). ThecyoD gene encodes subunit IV (12 kDa) (95,97,98), which is homologous to the counterpart in cytochromec oxidases from Gram-positive bacteria and terminal quinol oxidases but unrelated to eukaryotic cytochromec oxidases (96,99). ThecyoE gene, located at the 3′ end of thecyo operon, encodes no subunit of cytochromebo3 but does encode the enzyme that catalyzes the transformation of hemeB (protoporphyrin IX, or protoheme) to hemeO (uppercase letters in heme designations highlight the chemical nature of hemes, as opposed to protein-bound hemes) by attaching a long farnesyl side chain to the former (100,101,102). HemeO is specifically required for the binuclear oxygen-reducing site of cytochromebo3. Subunit I (CyoB) carries all three metal redox cofactors: low-spin hemeb, high-spin hemeo3, and a copper ion (CuB) (3,94,103,104). Hemeo3 and CuB form the heme-copper binuclear center for dioxygen reduction. Unlikeaa3-type cytochrome oxidase, subunit II (CyoA) does not have any metal redox cofactors. Subunits III (CyoC) and IV (CyoD) can be removed from cytochromebo3 without any loss of catalytic activity (38) but seem to be required for the assembly of the metal redox cofactors in subunit I (19,105).

Cytochromebd

Until recently, cytochromebd was thought to be a two-subunit oxidase (106) encoded by thecydAB operon (39,40,41), located at 16.6 min on theE. coli genetic map (39,93), and it was cloned (107) and sequenced (41). The molecular masses of subunit I (CydA) and subunit II (CydB) determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, 57 and 43 kDa (47), respectively, are consistent with those determined based on the corresponding DNA sequences, 58 and 42.5 kDa (41). Neither of these two major subunits of cytochromebd has homology to any subunit of other known respiratory chain oxidases, such as cytochromebo3 and cytochromec oxidases (41,108). However, very recently it has been reported that cytochromebd has an additional polypeptide named CydX (42,43). This small (4 kDa) protein seems to be the third subunit of cytochromebd. CydX is required for maintenance of the cytochromebd activity and contributes to stabilization of the hemes (42,43,80,109,110). Thus it is now clear that cytochromebd is a three-subunit oxidase encoded by thecydABX operon (21,42,43). Cytochromebd contains no copper atoms and does not pump protons (28,29,32,47,50). Therefore, cytochromebd is not a member of the heme-copper terminal oxidase superfamily. Cytochromebd subunits carry three hemes:b558,b595, andd (106,111). Hemeb558 is located on subunit I (CydA), whereas hemesb595 andd are likely to be in the area of the subunit contact (112). CydA can be expressed and purified without CydB by using mutant strains defective incydB (113). The purified CydA retains hemeb558 but lacks hemesb595 andd (113). In addition to thecydABX operon, two other genes,cydC andcydD of thecydCD operon, located at 19 min on theE. coli genetic map (114,115,116), are essential for the assembly of cytochromebd (114,116,117,118). CydC and CydD, however, are not subunits of cytochromebd. It was shown previously thatcydCD encodes a heterodimeric ATP-binding cassette-type transporter (ABC transporter) that is a transport system for the thiol-containing redox-active molecules cysteine and glutathione (21,119).

Regulation of Gene Expression

Under high oxygen tension,E. coli expresses cytochromebo3 (encoded bycyoABCDE), whereas cytochromebd (encoded bycydABX) is moderately repressed (22,23,24). The expression of thecyoABCDE andcydABX operons is controlled by the two global transcriptional regulators Arc and Fnr (2,23,120,121,122,123,124,125,126). Arc is a two-component regulatory system that includes ArcA, a cytosolic response regulator, and ArcB, a transmembrane histidine kinase sensor. ArcA controls several hundred genes (127) and responds to the oxidation state of the quinone pool, which is sensed by ArcB (128). ArcB is activated in the course of the transition from aerobic to microaerobic growth and remains active during anaerobic growth. Upon stimulation, ArcB autophosphorylates and then transphosphorylates ArcA (128,129). Under microaerobic conditions (i.e., oxygen tension of 2 to 15% of air saturation), the increased level of phosphorylated ArcA represses thecyoABCDE operon and activates thecydABX operon (130).

Another global regulator, Fnr (an oxygen-labile transcription factor regulating hundreds of genes), controls the induction of anaerobic processes inE. coli (131,132). The Fnr protein has an Fe-S cluster which serves as a redox sensor. The levels of the Fnr protein are similar under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions (122,133), but the protein is active only during anaerobic growth. The active Fnr protein represses bothcyoABCDE andcydABX operons during a transition to anaerobic conditions (i.e., oxygen tension of less than 2% of air saturation) (124,125,133).

PROSTHETIC GROUPS

Quinones

Quinones are lipophilic molecules dissolved within the lipid bilayer of the cytoplasmic membrane. TheE. coli membrane contains three types of quinones that all have an octaprenyl side chain (C40). These are a benzoquinone, ubiquinone, and two naphthoquinones, menaquinone and dimethylmenaquinone. Both cytochromebo3 and cytochromebd catalyze the two-electron oxidation of ubiquinol-8 to ubiquinone-8 (Fig. 2) (apparent midpoint redox potential [Em] = +110 mV [2]), coupled to the four-electron reduction of O2 to 2H2O (Em = +820 mV). Cytochromebd can also oxidize menaquinol-8 to menaquinone-8 (Fig. 2) (Em = −80 mV [2]) (26,27). Ubiquinone-8 is predominant during aerobic growth but is replaced by menaquinone-8 upon the transition from aerobiosis to anaerobiosis (2,134,135). It was shown previously that cytochromebo3 contains a tightly bound ubiquinone (136). The presence or absence of bound quinone in solubilized cytochromebd depends on the purification protocol (20). In some preparations of purified cytochromebd, there is no quinone (32,47,51,137), whereas others clearly contain bound quinone (52,54,138).

Figure 2.

Structures of ubiquinone-8, the reduced ubiquinone-8 (ubiquinol-8), menaquinone-8, and the reduced menaquinone-8 (menaquinol-8).doi:10.1128/ecosalplus.ESP-0012-2015.f2

Cytochromebo3 Prosthetic Groups

Cytochromebo3 contains three redox-active metal groups: a low-spin hemeb, which is involved in quinol oxidation, hemeo3, and CuB; the latter two groups compose a binuclear center, which is the site of the binding of O2 and its reduction to water. The chemical cofactors are hemeb, corresponding to protoporphyrin IX (protoheme, or hemeB); hemeo3, corresponding to the protoheme with a long farnesyl side chain attached (hemeO); and the CuB center, represented by the Cu atom ligated by three histidine residues. In the three-dimensional (3D) structure of cytochromebo3, all prosthetic groups were found to be within subunit I (139). In addition to the metal centers, there is also one tightly bound ubiquinone cofactor. Although the X-ray structure did not show any bound quinone in the crystallized enzyme, the site-directed mutagenesis studies identified residues that modulate the properties of the bound quinone (140,141,142).

Hemeb

Subunit I of thebo3 oxidase contains 15 transmembrane helices. Hemeb is located between helices II and X at a depth of about one-third of the membrane thickness from the P (positive) side and oriented perpendicular to the membrane plane, such that its propionates are exposed to the P side of the membrane. In both reduced (S [spin quantum number] = 0) and oxidized (S =1/2) states (143,144), the low-spin heme iron is bound to the four nitrogen atoms of the porphyrin ring and to the two conserved histidines of subunit I (H106I and H421I; subscript “I” identifies the subunit where the residue is). Hemeb is a direct electron donor for the catalytic binuclear site. It transfers electrons obtained from the bound ubiquinone. The Em of this heme is about +280 mV (without redox interaction) (48). The optical spectrum of this heme is rather characteristic for low-spin six-coordinate hemeb, with theα-band of the reduced heme at 562 nm in the absolute and the difference (reduced-minus-oxidized) absorption spectra. The maxima of theβ- and Soret bands of the reduced-minus-oxidized hemeb spectrum are at 530 and 430 nm, respectively. At a high level of cytochromebo3 expression, hemeB in the low-spin heme site can be replaced by hemeO (145). Such heme alteration does not decrease the enzyme activity but lowers the functionalKm of the enzyme for oxygen (36).

Hemeo3

Hemeo3 is the oxygen-binding heme, and the subscript 3 has been used historically to indicate this feature by analogy to the other heme-copper oxidases. Hemeo3 is a high-spin heme in both the fully reduced ferrous state (S = 2) (146) and the oxidized ferric state (S =5/2) (147). Depending on the conditions, hemeo3 may be penta- or hexacoordinate (147): the permanent bonds of the heme iron include four bonds with nitrogen atoms of the porphyrin ring and one extra bond with the conserved H419I from helix X at the same depth in the membrane as hemeb. Fivefold coordination of the heme iron leaves one side of the heme empty and available for the binding of ligands such as O2. This free coordination points toward the CuB, together with which hemeo3 forms the bimetallic catalytic site where the reduction of oxygen to water takes place. The spectrum of hemeo3 is characteristic of high-spin hemes. It has a broadα-band centered at 560 nm in the reduced-minus-oxidized spectrum with small extinction and an intense Soret band with the maximum at 430 nm (145). The redox properties of the high-spin hemeo3 are very similar to those of hemeb (48). Both of these hemes have a redox potential of about 280 mV when the neighboring heme is oxidized, but the reduction of the neighbor results in a 100-mV lowering of the heme potential (redox interaction).

CuB

The second partner in the binuclear catalytic site is CuB. The oxidized CuB is a tetragonal center (148,149); it has three permanent axial histidine imidazole ligands and one mobile oxygen ligand with an exchangeable proton(s) (148,149). The imidazole ligands originate from H284I in helix VI and from H333I and H334I, both located in a loop fragment between helices VII and VIII. This redox center is often called the invisible Cu site because it does not show any changes in optical spectra upon enzyme reduction and oxidation. Usually, the electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) signal from the oxidized Cu can be easily detected, but the close proximity of the iron atom of hemeo3 results in strong magnetic interaction and the absence of any detectable spectrum of CuB. Such strong magnetic interaction, however, can help to define the Em of the tetragonal center. The reduction of the Cu ion brakes magnetic interaction with the high-spin heme, and the appearance of a high-spin EPR signal can give information on the reduction level of CuB. With such an approach, an Em of +370 mV for CuB was obtained (48).

Bound ubiquinone

It has been proposed that thebo3 oxidase can have two ubiquinone-binding sites with different affinities. The bound ubiquinone in the site with high affinity for ubiquinone (the QH site) can be considered to be the enzyme cofactor (136,150,151,152). At the same time, in the low-affinity (QL) site, fast exchange of the ubiquinone molecules occurs, and it was proposed that electrons are transferred from the QL site to the next electron acceptor (hemeb) via the QH site (136,153). A functional study of mutants obtained by site-directed mutagenesis was used to create a model for the possible QH binding site, which is located in subunit I, close to hemeb (139). According to this model, the QH site is predicted to form up to four hydrogen bonds with D75 and R71 to the 1-carbonyl oxygen and with H98 and Q101 to the 4-carbonyl oxygen. EPR spectroscopy demonstrated that the QH site stabilizes a semiquinone anion radical of bound ubiquinone (154,155,156).

Cytochromebd Prosthetic Groups

Cytochromebd is composed of three subunits, I (CydA), II (CydB), and III (CydX), which are typical integral membrane proteins. The subunits carry three metal-containing redox centers, such as two protoheme IX groups (hemesb558 andb595) and a chlorin molecule (hemed) (Fig. 3), which are proposed to be in 1:1:1 stoichiometry per the enzyme complex, but no copper ion (157,158,159,160,161). Hemeb558 appears to be located within subunit I. Subunits I and II are required for the assembly of hemeb595 and hemed, suggesting that these two hemes may reside at the subunit interface (112). Both hemeb558 and hemed are presumed to be oriented with their heme planes perpendicular to the membrane plane. Hemeb595 is possibly oriented with its heme plane at ∼55° with respect to the plane of the membrane (162).

Figure 3.

Structures of hemeB (protoheme IX), hemeO, and hemeD (chlorin), which are redox cofactors of cytochromebo3 and/or cytochromebd fromE. coli.doi:10.1128/ecosalplus.ESP-0012-2015.f3

Hemeb558

Hemeb558 was shown to be located on subunit I. Although subunits I and II of the isolated cytochromebd complex cannot be split apart without denaturing the enzyme, some genetic approaches have allowed subunit I to be synthesized in the absence of subunit II (113). Antibodies directed against subunit I (163,164), as well as selective proteolysis of this subunit (165,166), inhibit the ubiquinol oxidase activity of cytochromebd. These findings suggest that hemeb558 is associated with subunit I and involved in quinol oxidation. Theα-band of the reduced hemeb558 reveals a peak at 560 to 562 nm in the absolute and the difference (reduced-minus-oxidized) absorption spectra at room temperature. The maximum of theβ-band of the reduced heme is at 531 to 532 nm (167,168). The difference absorption spectrum of hemeb558 in the Soret region reveals a maximum at 429 nm and a minimum at 413 nm (168). The positions of these bands were confirmed upon redox titration by separating the composite difference absorption spectra of the enzyme into the contributions of the individual heme components (111,169) as well as by the detailed spectroelectrochemical redox titration and numerical modeling of the data (168). Low temperature (77 K) shifts all bands by 1 to 4 nm to the blue (167). Hemeb558 is a low-spin hexacoordinate (170,171,172), and amino acid residues H186 and M393 of subunit I were identified as its axial ligands (173,174,175). The location of hemeb558 is predicted to be near the periplasmic surface (176,177).

Hemeb595

The band with a maximum at ∼595 nm in the difference (reduced-minus-“air-oxidized”) absorption spectrum of cytochromebd was long ascribed to hemea1 because of the relatively bathochromic position of the extremum (178). Subsequently, it was established that the prosthetic group of this component is not hemea but protoheme IX (47,111), whereupon the component has been called hemeb595. Magnetic circular dichroism (MCD) studies confirmed such a conclusion (170,172). The difference absorption spectrum of hemeb595 in the visible region was resolved from a set of composite spectra of the isolated cytochromebd recorded at different redox potentials (111,169). It turned out that this spectrum is similar to that of catalases and peroxidases, containing pentacoordinate (high-spin) protoheme IX (111,168). Hemeb595 shows anα-band at 594 nm and aβ-band at 561 nm in the difference absorption spectrum (168). A trough at 643 nm in the difference spectrum of hemeb595 (168) is indicative of the disappearance of a charge transfer to the ligand band, characteristic of the oxidized high-spin hemeb, as in the case of peroxidases. Theγ-band of ferrous hemeb595 in the absolute absorption spectrum is characterized by a maximum at ∼440 nm, as clearly revealed by femtosecond spectroscopy (179). The difference absorption spectrum of hemeb595 in the Soret region shows a maximum at 439 nm and a minimum at 400 nm (168). Hemeb595 is a high-spin pentacoordinate (170,172) ligated by the histidine (H19) of subunit I (180) and located on the periplasmic surface (176,177). The role of hemeb595 remains obscure. It is proposed that hemeb595 participates in the reduction of oxygen, forming, together with hemed, a diheme oxygen-reducing site somewhat similar to the heme-Cu oxygen-reducing site in theaa3- andbo3-type oxidases (52,170,171,179,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189). In favor of this hypothesis is the finding that the circular dichroism (CD) spectrum of the reduced wild-type cytochromebd in the Soret band shows strong excitonic interaction between ferrous hemesd andb595 (171). Modeling the excitonic interactions in absorption and CD spectra yields an estimate of the Fe-to-Fe distance between hemed and hemeb595 to be about 10 Å (171). In the opinion of other researchers, the function of hemeb595 is limited to the transfer of an electron from hemeb558 to hemed (190,191). Some authors believe that hemeb595 can form a second site capable of reacting with oxygen (35,157).

Hemed

Hemed is a chlorin-type molecule (192). Theα-band of the reduced hemed in the absolute absorption spectrum shows a peak at 628 to 630 nm (89). However, under usual conditions, hemed is in the stable oxygenated (oxygen-ligated ferrous) form, which is characterized by a band with a maximum at 647 to 650 nm in the absolute absorption spectrum (193). The reduced-minus-oxidized difference spectrum of hemed in the Soret region shows a maximum at 430 nm and a minimum at 405 nm (168). The spectral contribution of hemed to the complexγ-band is much smaller than those of either hemesb (168). Hemed is predicted to be located near the periplasmic surface (176,177). This heme is the place for capturing and reducing O2 to 2H2O. Being free of external ligands, hemed seems to be in the high-spin state. The protein ligand of hemed is not known. The data on the nature of the hemed axial ligand are controversial. Authors of resonance Raman and electron nuclear double resonance studies have claimed that it cannot be an ordinary histidine, cysteine, or tyrosinate but is either a weakly coordinating protein donor or a water molecule (180,194,195). In contrast, EPR studies have indicated that the hemed axial ligand is histidine in an anomalous condition or another nitrogenous amino acid residue (196). Finally, it has been reported recently that the highly conserved glutamate 99 of subunit I may be a candidate for such a role (137).

The millimolar extinction coefficients used commonly for the determination of theE. coli cytochromebd concentration are listed inTable 3.

Table 3.

Extinction coefficients used for determination of theE. coli cytochromebd concentration

| Absorption spectrum | Heme(s) | Wavelength paira (nm) | Δεb (mM−1·cm−1) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference spectra | ||||

| Fully reduced minus as prepared | d | 628–607 | 10.8 | 170 |

| d | 628–651* | 27.9 | 182 | |

| d | 628–649* | 18.8 | 32 | |

| b558 | 561–580 | 21 | 182 | |

| b595 | 595–606.5 | 1.9 | 182 | |

| All | 429–700† | 303 | 182 | |

| Fully reduced CO bound minus fully reduced | d | 642–622 | 12.6 | 32 |

| d | 643–623 | 13.2 | 54 | |

| Absolute spectra | ||||

| Fully reduced | d | 628–670 | 25 | 52 |

| As prepared | All | 414–700† | 223 | 182 |

Values marked with an asterisk or dagger cannot be recommended for the determination of the cytochromebd concentration since, for those marked with an asterisk (*), the as-prepared enzyme contains various amounts of the ferrous hemed-oxy complex that absorbs at 649 to 651 nm and, for those marked with a dagger (†), the intensity of the Soret band is variable depending on the purity of the preparation.

Δε, extinction coefficient.

Redox Potentials of Hemes in Cytochromebd

The Em values of hemesb558,b595, andd in theE. coli cytochromebd solubilized inn-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside at pH 7.0 are +176, +168, and +258 mV, respectively (49) (Table 1). Similar values were reported for cytochromebd contained in bacterial membranes (158,159,197), reconstituted in liposomes (198), or solubilized in Tween 20 or Triton X-100, in which the enzyme is active (198). Notably, the Em value of hemeb558 can depend on the detergent used for solubilization (198). In particular, octylglucoside and cholate cause a large decrease in the Em value of hemeb558 that also correlates with the reversible inactivation of the enzyme (198). The Em values of all three heme components of cytochromebd are sensitive to pH values between 5.8 and 8.3, with dependence of −61 mV per pH unit for hemed and −40 mV per pH unit for hemesb558 andb595, indicating that the reduction of thebd complex is accompanied by enzyme protonation (198). The spectroelectrochemical redox titration and spectral modeling show the strong redox interaction between hemeb558 and hemeb595, while the interaction between hemed and either hemesb is insignificant (168). Of interest, in the absence of hemed the interaction potential between hemeb558 and hemeb595 is much larger compared with the situation when hemed is present (168).

STRUCTURE OFbo3 ANDbd OXIDASES

3D Structure ofbo3 Oxidase

The 3D structure of thebo3 oxidase fromE. coli at 3.5-Å resolution was reported in 2000 (139). The structure confirms that the overall architecture of this complex is very similar to those of all other members of the heme-copper oxidase superfamily. The whole integral protein contains 25 transmembrane helices, of which subunit I has 15, subunit II has only 2, subunit III has 5, and subunit IV has 3 helices. All known enzyme cofactors were found in subunit I. The transmembrane helices of this subunit are not perpendicular to the membrane plane but are tilted about 20 to 35° against it. When viewed from the top (P side), they are arranged in an anticlockwise direction and form three semicircular arcs, organized in a quasithreefold axis of symmetry. Three pores are formed in the center of the arcs. One pore houses the binuclear center (hemeo3 and CuB) of the oxidase and includes the proton-conductive K channel directed from the binuclear center toward the N (negative) side of the membrane. Another pore retains hemeb; the last pore is devoid of cofactors but is used for the proton-conductive D channel.

Hemeb is located at a depth of about one-third of the membrane thickness from the P side and oriented perpendicular to the membrane plane, such that its propionates are pointing toward the P side of the membrane (Fig. 4). The hemeo3 is located at the same depth as hemeb, the plane of hemeo3 is also perpendicular to the membrane, and the propionates point toward the P side in a manner similar to hemea. Hemeb and hemeo3 are facing each other at an angle of 104 to 108o. At an ∼5-Å distance from the iron of hemeo3, a copper atom designated CuB is located. In addition to this Cu atom that is coordinated by the three histidines, there is another important structure identified in all heme-copper oxidases and represented by the covalently bound H284I and Y288. The three histidines and the tyrosine form a conjugated π-electron system around the CuB center. Cytochromebo3 has been proposed to have two ubiquinone-binding sites, one with high (QH) and one with low (QL) affinity for ubiquinone (136). It has also been postulated that electrons are transferred from the QL site to hemeb via the ubiquinone bound at the QH site. Site-directed mutagenesis studies (140,142) have identified residues that modulate the properties of the QH site. The model of a QH quinone-binding site including R71, D75, H98, and Q101 residues is also supported by the results of X-ray crystallography (139).

Figure 4.

Structure of cytochromebo3 fromE. coli. Only two main subunits are shown: subunit I in gray and subunit II in yellow. Hemes are shown in red (hemeo3 on the right and hemeb on the left). The cyan sphere near hemeo3 represents the CuB center. The amino acid residues of possible proton-conducting pathways, the D (red-tag) and K (blue-tag) channels, in subunit I are shown. The most likely position of the membrane is depicted by the gray background.doi:10.1128/ecosalplus.ESP-0012-2015.f4

The protein medium itself cannot facilitate proton delivery toward the binuclear center or across the membrane, and in order to overcome this limitation, the oxidase has special proton-conductive structures. It is proposed that these structures are based on chains of hydrogen bonds between hydrogen-bonding protein side groups (polar and/or protonatable) and water molecules, whereby the proton is transferred via a Grotthuss type mechanism. At least two proton-conductive channels have been identified primarily by site-directed mutagenesis (199,200,201), and these findings were later confirmed by X-ray crystallography (139). One of them is the so-called K pathway, named after the highly conserved lysine 362 (199,200), which is situated approximately halfway through the channel (Fig. 4). This pathway starts with S315 and S299 and continues through conserved residues K362I and T359I toward the hydroxyethyl farnesyl side chain of hemeo3 and Y288I in the proximity of the binuclear center. The other channel is named D after the highly conserved D135I (201,202), which is situated near the surface of the enzyme on the N side. D135I, together with T211I, forms a mouth that leads via polar residues N124I, N142I, S145I, T149I, T201I, and T204I to E286I (Fig. 4), which is an important residue for the proton-pumping mechanism.

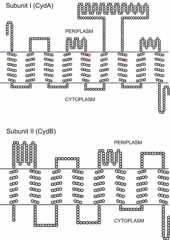

Proposed Structure of Cytochromebd

To date, the X-ray structure of cytochromebd is not available; however, the findings from conventional studies of the protein topology in the membrane suggest that all three hemes are located near the periplasmic side of the membrane (176,177).Figure 5 shows topological models of subunits I (CydA) and II (CydB) of cytochromebd fromE. coli (27). Both subunits are integral membrane proteins showing no sequence homology to the subunits of the heme-copper oxidase superfamily (e.g., cytochromebo3). Subunit I consists of nine transmembrane helices, with the N terminus in the periplasm and the C terminus in the cytoplasm (176). Subunit II is composed of eight transmembrane helices, with both N and C termini in the cytoplasm (176). Newly discovered subunit III, the 37 amino acid CydX protein (42,43,109), is proposed to consist of the only membrane-spanning helix, with the N terminus in the cytoplasm and the C terminus in the periplasm (21,80,109). Subunit I contains a large hydrophilic domain, which is called the Q-loop, connecting transmembrane helices VI and VII. As shown by many experimental approaches, the Q-loop is involved in quinol binding and oxidation (163,164,165,166,203,204). Thus, the quinol-oxidizing site in cytochromebd is located on the periplasmic side of the membrane. It is worth mentioning that the size of the Q-loop is taken into account to categorize the bacterial cytochromesbd (20,172).

Figure 5.

Proposed topology of the CydA and CydB subunits of cytochromebd fromE. coli. The axial ligands of hemeb595 (H19) and hemeb558 (H186 and M393) in the CydA subunit are shown in purple and red, respectively. The protein sequence data have been taken from information available athttp://genolist.pasteur.fr/Colibri/. The alignment has been made by using the TOPO2 program available athttp://www.sacs.ucsf.edu/TOPO2. The model is very similar to that reported in reference27.doi:10.1128/ecosalplus.ESP-0012-2015.f5

Based on 815 sequences of the cytochromebd gene available, it was possible to search for highly conserved residues in the corresponding protein (27). It was shown previously that subunit II evolved significantly faster than subunit I, with the result that subunit II exhibits greater sequence diversity (205). A number of residues in subunit I are totally (>99%) conserved in the 815 sequences (27). These residues include H19 (the hemeb595 axial ligand [180]), H186 and M393 (the hemeb558 axial ligands [173,174,175]), K252 and E257 (involved in quinol binding [204]), R448 (having an unknown function), and E99, E107, and S140 (proposed to be components of a proton channel [54,176] and important for binding in the hemed-hemeb595 diheme site [27,137]). Slightly less conserved (95 to 99%) are E445 (required for charge compensation at the hemeb595-hemed oxygen-reducing site upon the full reduction of oxygen by two electrons [52]), N148 (a plausible component of a proton channel), and R9 (having an unknown function) (27). Somewhat less conserved (∼85%) are R391 (which stabilizes the reduced form of hemeb558 [206]) and D239 (having an unknown function); however, these residues are totally conserved within the group of cytochromesbd with a long Q-loop, to which theE. coli enzyme belongs (27). Other conserved residues are glycines, prolines, phenylalanines, and tryptophans, which may play structural roles. There is only one totally (>99%) conserved residue (W57) in subunit II (27). Residues R100, D29, and D120 of subunit II are totally conserved within the family of long-Q-loop cytochromebd, and the residue at position 58 in subunit II (according to the numbering for theE. coli enzyme) is either an aspartate or a glutamate. The N-terminal portion of subunit II is thought to be involved in the binding of hemed and hemeb595 (27,207).

A multiple sequence alignment of 299 homologues of the newly found CydX subunit reveals the conserved amino acid motif that includes the residues Y3, W6, G9, and E/D25 (109). Of these residues, the first three are part of the predicted transmembrane α-helix being localized to the same side of the helix (109). The latter suggests that this is possibly the side of the α-helix of CydX that interacts with the other subunits in cytochromebd (109).

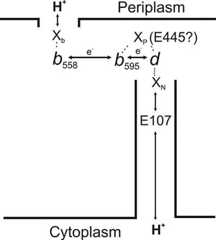

Since the active site of O2 reduction is located near the periplasmic surface and protons for H2O production are taken from the bacterial cytoplasm, there must be at least one transmembrane proton-conducting pathway to convey protons from the cytoplasm to the hemeb595-hemed site (51,52,54,176) (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Schematic model of electron and proton transfer pathways in cytochromebd fromE. coli. There are two protonatable groups, XP and XN, redox coupled to the hemeb595-hemed active site. A highly conserved residue, E445, was proposed to be either the XP group or the gateway in a channel that connects XP with the cytoplasm or the periplasm (52). A strictly conserved E107 residue is a part of the channel mediating proton transfer to XN from the cytoplasm (54). Xb, a group at the periplasmic side of the membrane that picks up and releases a proton as hemeb558, is reduced and oxidized.doi:10.1128/ecosalplus.ESP-0012-2015.f6

COMPARISON OF AFFINITIES OF THE TWO OXIDASES FOR OXYGEN

InE. coli, the affinity of cytochromebd for oxygen, i.e., dissociation constant for O2,KD (O2) of 0.28 μM (31), is about 1,000-fold higher than that of cytochromebo3,KD (O2) >0.3 mM (30), which allows us to consider thebd andbo3 enzymes as the high- and low-affinity oxidases, respectively. Such a striking difference in theKD (O2) values correlates with the following facts.

Cytochromebo3 predominates under high aeration, whereas cytochromebd is expressed maximally under low aeration (22,23,24).

A peculiar feature of cytochromebd is that it is purified mainly as a stable oxygenated (oxy)complex (hemeb5583+-hemeb5953+-hemed2+-O2) characterized by an absorption peak at 645 to 650 nm (193,208,209,210). The fact that a stable oxycomplex can be generated by the reversible binding of oxygen to the one-electron-reduced cytochromebd can be used for direct measuring of theKD (O2) of cytochromebd (31,49). This is not the case for cytochromebo3 or any other heme-copper oxidase, which in any redox state under normal conditions does not form a stable oxycomplex; therefore, theKD (O2) for cytochromebo3 can be determined only indirectly (30). For cytochromebo3, theKD (O2) is more than 100-fold higher than the apparentKm for O2, which allows us to conclude that thebo3 oxidase is designed to trap O2 kinetically by reducing it to an oxoferryl species (36). Because of its ability to function efficiently under microaerobic conditions, cytochromebd is required for commensal and pathogenicE. coli strains to colonize mouse intestine (57). It turns out thatE. coli mutants lacking cytochromebd, with high affinity for O2, are eliminated by competition with wild-type strains competent in respiration and that cytochromebo3, with low affinity for O2, is not necessary for colonization (57). The colonization defects of the cytochromebd mutants challenge the traditional view that the intestine is anaerobic (211) but support the hypothesis that a microaerobic niche is critical for both establishing and maintainingE. coli in the intestine (57).

BINDING OF LIGANDS (OTHER THAN OXYGEN)

Ligand Binding to the Cytochromebo3 Binuclear Center

Ligands that bind to the binuclear center of cytochromebo3 can be divided into two classes: uncharged molecules like CO and NO, which preferably bind to the binuclear center in the reduced form and induce the transition of the high-spin heme to the low-spin state, making it six coordinate, and ionizable molecules, like HCN and NaN3, or formate, which preferably bind to the oxidized heme. The binding of the second group of ligands can result in a different spin state for hemeo3. Some of the ligands can bind either to hemeo3 only or to a site between the two metals forming the binuclear center. The dynamics of ligand exchange can be used to characterize the possible dynamics of the binding of the substrate and the partial products of the reaction generated during the catalytic cycle.

CO and NO binding

The molecules of CO and NO mimic the oxygen molecule and can be bound to the catalytic site of cytochromebo3. This binding occurs with the high-spin heme of the reduced binuclear center. Carbon monoxide reacts with the reduced enzyme with a stoichiometry of 1:1, and theKD for this reaction was determined to be 1.7 × 10−6 M (147). The value of a second-order rate constant for association (kon) is 6.1 × 104 M−1·s−1.

The CO ligation of hemeo3 results in a blue shift of the heme absorption bands. The characteristic CO-binding spectrum has two small peaks in the visible part of the spectrum at 530 and 570 nm and a pronounced spectral shift in the Soret region, with the maximumλ of ∼415 nm and the minimumλ of ∼430 nm.

The photolysis of the reduced CO-bound enzyme at low temperatures results in the dislocation of the iron-bound CO to CuB, where it can be recognized by the specific C≡O stretch at ∼2,065 cm−1 due to CO bound to copper (212). At room temperature, the photodissociation of CO from the heme iron and its subsequent binding to CuB is an extremely fast reaction, and then CO remains bound to CuB for only a short time (two-component dissociation with the time constants of ∼14 and 140μs [213]). After carbon monoxide dissociation from the binuclear site, the rebinding to the heme iron via CuB occurs at a much lower rate (214). Yoshikawa et al. (215) have reported the crystallographic structures of the reduced bovine enzyme in the presence and absence of CO. While this X-ray study did not find any significant changes in the structure of CuB relative to the fully oxidized bovine enzyme, the extended X-ray absorption fine-structure (148) investigation of the first shell of CuB showed a dramatic change upon the addition of CO, which involves the dissociation of one of the CuB histidine ligands and its possible replacement by a chloride ion.

Fully reduced cytochromebo3 also binds NO with a stoichiometry of 1:1 and very high affinity (KD < 10−8 M) (216), forming the ferrous nitrosyl (Fe2+-NO) species, as determined by EPR spectroscopy (147). The hemeo3-NO complex yields well-resolved EPR signals from the14N atoms of both NO itself and the proximal histidine ligand of hemeo3, showing nuclear hyperfine coupling (147).

Reaction of cytochromebo3 with cyanide

Cyanide reacts almost exclusively with oxidized cytochromebo3. The reaction is manifested by a red shift of the Soret band from approximately 411 to 415 nm (217). A characteristic feature of the ligand-binding reaction in theα-band region is the loss of the broad charge transfer band at 630 nm. This band is attributable to the fully oxidized binuclear center in which hemeo3 is in a high-spin state. The results of EPR studies (217) seem to indicate that these absorption changes occur because the ferric high-spin hemeo3 becomes a ferric low-spin ligand complex. Because of the magnetic coupling with CuB2+, the EPR spectrum (gz [constant of magnetization] = 3.3) is observed only when the copper of the binuclear center is reduced. This signal is characteristic of the conversion of the ferric high-spin heme into the low-spin state by the binding of strong-field ligands such as cyanide (218). Cytochromebo3 binds a single equivalent of cyanide (KD, 1 × 10−6 to 2 × 10−6 M) with monophasic kinetics (219) andkon of 37 M−1·s−1 (at pH 6.0) (220). This rate constant is slightly pH dependent and increases about 1.8-fold over the pH range between 6.0 and 8.5 (220). Room-temperature MCD spectra in the near-infrared region (221), results from infrared and EPR studies (222), and also resonance Raman detection (223) of the product of the reaction of the oxidized cytochromebo3 with cyanide have led us to propose the bridging structure of the cyanide complex to be as follows: Feo33+—C=N—CuB2+, where Feo3 is the iron of hemeo3. It was also shown that the reduction of the enzyme results in the release of the CuB ligation and the formation of an Feo32+—C=N moiety.

Reaction of cytochromebo3 with azide

Azide binds to cytochromebo3 with a stoichiometry of 1:1; theKD for this reaction is about 2 × 10−5 M (224). Contrary to the addition of cyanide, the addition of azide to the oxidized isolated enzyme causes a relatively rapid but small blue shift in the Soret band from approximately 411 to 409 nm. Simultaneously, the broad charge transfer band at 630 nm becomes more pronounced and shifts its maximum to 640 nm. These small changes induced in the electronic absorption spectrum are consistent with hemeo becoming hexacoordinate but remaining high spin, which can also be seen by MCD spectroscopy in the range of 350 to 1,100 nm (221,224). The kinetics of azide binding is an order of magnitude faster than that observed for the binding of cyanide. The calculatedkon for the binding of azide to cytochromebo3 is about 800 M−1·s−1 at pH 7.5. Thekon shows a marked increase upon acidification, indicating that the active species is electroneutral hydrazoic acid. Analyses of EPR, electronic, and MCD spectra (219) were used to prove that, unlike cyanide, azide does not bind to hemeo3 but rather to the CuB site, whereas the resolved 3D structure of the bovine cytochromec oxidase in the presence of azide revealed the bridging structure of the complex (Fea33+—N=N=N—CuB2+) (215). The Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) study of the bovine enzyme complex (225) showed a major infrared band at 2,051 cm−1. Subsequently, an FTIR spectroscopic study of theE. coli bo3 oxidase (226) showed an infrared band at 2,041 cm−1, which was assigned to the bridging structure. Discrepancy in the ligation geometry found by the different methods was resolved by detailed analysis of the FTIR spectroscopy of the complex of cytochromebo3 with asymmetrically15N-labeled azide (227). The experiments showed time-dependent evolution of the geometry of azide binding. In the air-oxidized form, a major infrared azide antisymmetric stretching band corresponds to the bridging geometry. An additional band developing at 2,062.5 cm−1 during longer incubation reflects the appearance of the CuB2+—N=N=N structure. In addition, the partial reduction of the oxidase withβ-NADH caused the appearance of new infrared bands indicating the emergence of the Feo3+—N=N=N configuration (227).

Ligand Binding to Cytochromebd

Since hemesd andb595 in cytochromebd are in the high-spin pentacoordinate state, these redox centers can potentially bind ligands. It has to be expected that the reduced form of thebd enzyme can bind mainly electroneutral molecules like O2, CO, and NO and that the oxidized cytochromebd binds ligands in the anionic form, such as cyanide and azide. It appears that hemed binds ligands readily but that the ligand reactivity of hemeb595 is minor (170,184,189). It was reported previously that hemeb558, although a low-spin hexacoordinate, may also bind ligands (e.g., CO and cyanide) to some extent (170,189). Such marginal reactivity is due possibly to the weakening of the bond of the methionine axial ligand (M393) with the hemeb558 iron caused by the isolation procedure and/or protein denaturation (189).

CO binding

CO brings about a red shift of the hemed band, with a maximum at 643 to 644 nm, a minimum near 624 nm, and a peak at 540 nm. In the Soret band, CO binding to fully reduced cytochromebd results in an absorption decrease and minima at 430 and 442 to 445 nm. Absorption perturbations in the Soret band and at 540 nm occur in parallel with the changes at 630 nm and reach saturation at 3 to 5μM CO. The peak at 540 nm is probably either theβ-band of the hemed-CO complex or part of its splitα-band (189). A peculiar W-shaped curve in the Soret region of the difference spectrum can be caused by a small band shift for unligated hemeb595 induced by CO interaction with the nearby hemed (179,185). Only a small fraction of hemeb595 in cytochromebd binds CO at room temperature or low temperatures (from −70 to −100°C) (170,184). CO binding with about 15% of hemeb595 in the membrane-bound cytochromebd at a cryogenic temperature (4 K) was observed with the aid of FTIR spectroscopy (181). The apparentKD for the CO complex with fully reduced cytochromebd appeared to be ∼80 nM (189). This value is markedly higher than that for cytochromebo3 (1.7μM) (147). The fully reduced cytochromebd can form a photosensitive hemed-CO complex, and following flash photolysis, CO recombines with ferrous hemed proportionally to the CO concentration, withkon of 8 × 107 M−1·s−1 (161) (Table 4). This value is much higher than that for cytochromebo3 (6.1 × 104 M−1·s−1) (147).

Table 4.

Kinetic and thermodynamic parameters for the reaction ofE. coli cytochromebd with O2, CO, and NO at room temperature

| Value for ligandg: | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | O2 | CO | NO | |||

| MV O2 | R-O2 | MV CO | R-CO | MV NO | R-NO | |

| kon (M−1 s−1) | 2 × 109b,e | 8 × 107b | ||||

| koff (s−1)f | 78 ± 0.5a | 4.2 ± 0.34a | 6.0 ± 0.2a | 0.036 ± 0.003a | 0.133 ± 0.005a | |

| KD (nM) | 280c | 80d | ||||

Data from reference75.

Data from reference161.

Data from reference31.

Data from reference189.

Data from reference53.

koff values are means ± standard deviations.

R-O2, R-CO, and R-NO are complexes of fully reduced cytochromebd with O2, CO, and NO, respectively. MV O2, MV CO, and MV NO are complexes of one-electron-reduced cytochromebd with O2, CO, and NO, respectively.

CO can also react with one-electron-reduced oxygen-free cytochromebd ofE. coli, forming a mixed-valence (MV) CO compound in which bothb-type hemes remain oxidized (hemeb5583+-hemeb5953+-hemed2+-CO) (75,179,185,188). The hemed α-band is also positioned at 635 to 636 nm in the absolute absorption spectrum.

It was proposed that the redox state of theb-type hemes in cytochromebd, presumably that of hemeb595, controls the status of the pathway for ligand transfer between hemed and the bulk phase (75,179). Two observations allowed us to draw such a conclusion.

Flash photolysis of the CO complex of the fully reduced cytochromebd results in the complete photodissociation of the CO molecule into the bulk. If the experiment is repeated with the MV CO complex, a significant part of the CO flashed off hemed2+ (up to 70%) gets trapped inside the protein and undergoes geminate recombination with hemed2+ on a subnanosecond time scale (179).

The apparent off rate constant for the spontaneous dissociation (koff) of CO from hemed2+ is markedly lower for the MV state of cytochromebd than for the fully reduced state of thebd oxidase (75) (Table 4).

Interaction with some nitrogen-containing ligands

A number of small nitrogen-containing molecules can react with fully reduced cytochromebd fromE. coli. NO3−, NO2−, N2O32− (trioxodinitrate), NH2OH, and NO, when added to membranes containing cytochromebd or the purified enzyme, give the decrease in amplitude and shift the 630-nm band of ferrous hemed to 641 to 645 nm (73,75,157,170,196,228,229,230,231). The common peak position was interpreted as all ligands yielding the same or very similar heme-nitrosyl compounds (231). A red shift of theα-band of hemed2+, observed upon the interaction of nitrite with the fully reduced membrane-bound cytochromebd, was accompanied by the slower formation of a trough at 438 nm in the difference (nitrite-treated-minus-reduced) absorption spectrum. These changes in the Soret band were ascribed to the formation of the product of the interaction of hemeb595 with nitrite (hemeb5952+-NO) (157).

Cytochromebd can also form a stable complex with NO in an MV state, in which ligand-bound hemed is reduced (to hemed2+) while the other two hemes (b558 andb595) are oxidized (75,196). The rates of NO dissociation from hemed2+ of cytochromebd in both the fully reduced and MV states were determined previously (75). In the fully reduced state, NO dissociates from hemed2+ at an unusually high rate, 0.133 s−1 (75), which is ∼30-fold higher thankoff measured for the ferrous hemea3 of the mitochondrial cytochromec oxidase, 0.004 s−1 (232). These data are consistent with the proposal that in heme-copper oxidases, CuB acts as a gate, controlling ligand binding to the heme in the active site (233). Another remarkable feature of NO dissociation from cytochromebd is that thekoff value for the MV state (0.036 s−1), although still quite high, is significantly lower than that measured for the fully reduced enzyme (75) (Table 4). The same effect was observed with CO (see above) (75). These data show that the redox state of hemeb595 controls the kinetic barrier for ligand dissociation from the active site of cytochromebd. The unusually high rate of NO dissociation from cytochromebd may explain the observation (73) that the NO-poisoned cytochromebd recovers respiratory function much more rapidly than a heme-copper oxidase.

Of interest, cytochromebd is not inactivated by up to 100 μM peroxynitrite, another nitrogen-containing harmful reactive species (72). Furthermore, cytochromebd in turnover with O2 is able to rapidly metabolize peroxynitrite with an apparent turnover rate increasing at higher concentrations of the reducing substrates (72). Thus, cytochromebd appears to be highly resistant to peroxynitrite damage (71,72). It is suggested that the expression ofbd-type instead of heme-copper-type oxidases enhances bacterial tolerance to nitrosative and oxidative stresses, thus promoting the colonization of host intestine or other microaerobic environments (68,69,70,71,72,75,76).

Reaction with cyanide

An earlier spectrophotometric study of the reaction of cytochromebd fromE. coli with KCN was performed with the membrane vesicles (234) and was confined to measurements in theα-band. That work revealed a decay of the absorbance at 650 nm induced by cyanide, and this finding was interpreted at that time to represent the disappearance of the free form of ferric hemed (234). This result was reinterpreted later as the decay of the ferrous hemed oxycomplex (167). Cyanide, interacting with the oxygenated form of the isolated cytochromebd, brings about significant absorption changes in theγ-region: a maximum at 434 to 437 nm and a minimum near 405 to 410 nm in the difference (KCN-treated-minus-oxygenated) spectrum. There is also considerable increase in the MCD signal in the Soret region. These data were interpreted to indicate the ligand-induced transition of high-spin hemeb595 to the low-spin state (235). Subsequently, a simple and fast method for the conversion of the oxygenated enzyme into the fully oxidized form with the use of lipophilic electron acceptors was developed (193). This approach enabled researchers to study the interaction of cyanide and other ligands with the homogenous oxidized preparation of cytochromebd. It was found that the addition of KCN to the fully oxidized cytochromebd brings about some absorption changes in the visible range of the difference absorption spectrum (the 624-nm peak is most pronounced) (170). These changes suggest the reaction of the ligand with hemed. A typical bathochromic shift of theγ-band is also observed. While the changes in the visible region are virtually saturated at 0.5 mM KCN, the Soret band effect continues to grow, indicating a second low-affinity ligand-binding site (170). The MCD spectrum of the fully oxidized cytochromebd is dominated by an asymmetric signal in the Soret region. Submillimolar cyanide has no effect on the initial MCD spectrum. KCN at 50 mM induces minor changes of the MCD signal in the Soret band, which can be modeled as the transition of a part of the low-spin hemeb558 (15 to 20%) to its low-spin cyanocomplex (170). There is no evidence of the interaction of high-spin ferric hemeb595 with the ligand. The apparent discrepancy between data on the interactions of cyanide with oxygenated (235) and fully oxidized (170) forms of thebd enzyme may derive from the fact that, in the former case, there seemed to be partial reduction of hemeb595 associated with ligand-induced electron transfer from hemed rather than a change of the hemeb595 spin state. On the basis of EPR spectra, Tsubaki et al. (182) proposed that the treatment of air-oxidized cytochromebd with cyanide results in a cyanide-bridging species with a hemed3+—C=N—hemeb5953+ structure. However, Tsubaki et al. (182) did not account for the electron released from hemed upon cyanide binding to as-prepared cytochromebd.

Interaction with H2O2

The addition of excess H2O2 toE. coli membranes containing cytochromebd (236) and the purified enzyme in the as-prepared (183,209) or the fully oxidized (51,183,237) state gives rise to an absorption band at ∼680 nm. The reaction of H2O2 with fully oxidized cytochromebd also induces a bathochromic shift of theγ-band (183,237). H2O2 binds to ferric hemed with an apparentKD of 30μM, but it seems not to interact with hemeb595 (183,237). The fully ferric cytochromebd reacts with peroxide withkon of 600 M−1·s−1. The decay of the H2O2-induced spectral changes upon the addition of catalase (at a rate of ∼10−3 s−1) is about 20-fold slower than expected for the dissociation of H2O2 from the complex, with hemed assuming a simple reversible binding of peroxide (koff =KD ×kon ∼ 2 × 10−2 s−1) (237). This finding suggests that the interaction of H2O2 with cytochromebd is essentially irreversible, giving rise to the oxoferryl state of hemed (237). The assignment of compound 680 to the oxoferryl state of hemed is confirmed by resonance Raman spectroscopy data (160). The results of resonance Raman spectroscopy studies suggest that hemed is in the high-spin pentacoordinate state when it is oxygenated (Fe2+-O2) or exists as an oxoferryl species (Fe4+-O2−) or in a compound with cyanide (238).

Remarkably, the isolated cytochromebd displays some peroxidase enzymatic activity (84). Moreover, cytochromebd, either purified or overexpressed in a catalase-deficientE. coli strain, shows a significant catalase activity that is insensitive to NO (71,85,86). Therefore, one may conclude that thisbd-type terminal oxidase actually contributes to protectE. coli from H2O2 stress.

PROPOSED MECHANISMS OF FUNCTIONING

Mechanism of Cytochromebo3 Functioning

Cytochromebo3 catalyzes the final step ofE. coli respiration—the oxidation of ubiquinol-8 and the reduction of molecular oxygen. The reduction of one dioxygen molecule to water requires four electrons, which are supplied by two molecules of ubiquinol on the P side, and four protons, taken up from the N side of the membrane. The reduction of oxygen to water is an exergonic process, coupled with the release of large amounts of energy. This energy is conserved in the form of ΔμH+. The formation of ΔμH+ by cytochromebo3 is based on two principles: vectorial chemistry and proton pumping. Since the protons and electrons for oxygen reduction to water are taken from different sides of the membrane, the reduction results in the net transfer of four charges across the membrane. At the same time, the enzyme is able not only to catalyze the oxygen reduction, but also to utilize the released energy for proton pumping. This process was discovered in 1977 (239) by the demonstration that the reduction of molecular oxygen to water by mitochondrial cytochromec oxidase is linked to the pumping of additional four protons across the membrane dielectric (239). Later, such functional ability was shown for cytochromebo3 (240). Hence, the overall reaction catalyzed by cytochromebo3 can be described by the following equation:

where Q is ubiquinone, QH2 is ubiquinol, H+N is proton taken from the N side of the membrane (the cytosol), and H+P is proton released to the P side of the membrane (the periplasmic space). The mechanism coupling electron transfer reactions with the transmembrane proton translocation is still under debate. Let’s look through the main elements of this mechanism.

Electron transfer reactions in cytochromebo3

The general sequence of electron transfer in thebo3 oxidase is well established. The ubiquinone molecule occupying the QH-binding site has a stable semiquinone form (241), which ensures the coupling of a one-electron redox reaction to a two-electron donor. A pulse radiolysis study showed that the quinone bound at the QH site is important for the rapid reduction of hemeb but not for rapid electron transfer from hemeb to the hemeo3-CuB binuclear center (242). The rate constant of electron transfer between semiquinone and hemeb was found to be 1.5 × 103 s−1 (242).

In the next step, the low-spin heme delivers electrons to the binuclear site in a controlled fashion that is coupled to proton translocation across the membrane (243). The rate of this electron transfer without coupling to the reaction with protons has been studied extensively, in particular, by the photodissociation of CO from the oxygen-binding heme in the so-called mixed valence form of the enzyme, where only the binuclear-site metals are initially reduced (244,245). (Note that the term “mixed valence” means two-electron-reduced form for cytochromebo3 but one-electron-reduced form for cytochromebd.) Primarily, it was found that this rate is about 3μs (3 × 105 s−1), which is too low to correspond to the pure electron tunneling, especially since this rate is independent of pH and substitution with heavy water (246,247) and therefore may not be presumed to be linked to proton transfer. The obtained value is, however, about three orders of magnitude lower than the value predicted by the empirical electron transfer theory (248,249). The results of recent femtosecond experiments show that the electron transfer from CO-dissociated ferrous hemeo3 to the low-spin ferric hemeb takes place at a rate of 8.3 × 108 s−1 (1.2 ns).

The final step of electron transfer reactions between hemeo3 and CuB has not been a subject for experimental determination, but, from our modern understanding of electron transfer reactions, the rate of transfer between the two metal atoms in the binuclear catalytic site can be predicted to be in the order of picoseconds, taking into account the very small distance (∼5 Å) between these atoms.

The suggested electron transfer sequence in cytochromebo3 can be described by the following equation:

Proton transfer reactions in cytochromebo3

The proton transfer pathways in cytochromebo3 have been investigated much less than the electron transfer pathways. There are no well-identified places for proton localization during the transfer of protons across the membrane, except the glutamate residue at position 286 (250,251,252) in the middle of the membrane. The quality of the X-ray structure of thebo3 oxidase was not sufficient to resolve individual water molecules in the proton-conducting channels. However, a very high level of structural homology to the other members of the heme-copper superfamily allows us to draw some conclusions about proton movements in the protein milieu including structural water arrays (253,254) in two well-defined proton channels. Both of these channels serve as proton delivery pathways and cross about two-thirds of the membrane dielectric from the cytoplasmic side to the binuclear catalytic site. The functional separation of the channel is not yet completely clear. Originally, models of the proposed molecular mechanism of proton pumping predicted the existence of two proton-conductive structures with different functions. One channel was proposed to be responsible for the translocation of “pumped” protons and the other for the uptake of “chemical” protons for water formation (255,256). The resolved structure revealed the existence of two such channels (named the D and K channels), and, originally (257), it was proposed that the D channel was responsible for the translocation of pumped protons and that the K channel was used for the uptake of chemical protons for water formation. However, more recent results indicate that the D channel is involved in the uptake not only of all four pumped protons, but also of two chemical protons used in the oxidative part of the catalytic cycle (258) and that the K channel is responsible for the uptake of another two chemical protons during the reductive part of the cycle (259,260). The proton translocation mechanism also requires two proton exit channels—one for proton release upon the oxidation of bound ubiquinol and the other for the release of the pumped protons. The 3D structure did not show clear exit pathways. However, the exit pathways should be much shorter than the D and K channels, only one-third of the membrane dielectric. In addition, in the well-resolved structures of bovine (261) andRhodobacter sphaeroides (254)aa3 oxidases, areas rich in structural water molecules, which can serve as exit channels, were found above the heme propionates. The results of site-directed mutagenesis studies suggested that the exit for pumped protons may start at conserved residues R481 and R482 (262), which are hydrogen bonded to the Δ-propionates of the hemes, and then continue further through the chains of mobile water molecules.

Cytochromebo3 catalytic cycle

The catalytic cycle for the reduction of oxygen to water is a rather complex process. One enzyme turnover includes the delivery of four electrons and four protons to the catalytic site, the binding of oxygen in this site, the translocation of four protons across the membrane, and the release of the product (two water molecules). This complexity is the reason why the real-time measurement of a single catalytic cycle shows a large number of intermediate states of the enzyme.

The reaction starts from the very fast (kon = 1.6 × 108 M−1·s−1 [30,263]) formation of an oxygen adduct, so-called compound A, which is characterized by an oxygen molecule bound to a high-spin hemeo3, as in hemoglobin.

Unlike that of hemoglobin, the lifetime of this intermediate is very short. In 24μs (263), the bound oxygen accepts electrons from CuB and hemeb and a proton, which results in O—O bond splitting and the formation of a peroxy intermediate. This compound was named “peroxy” because it can be produced by an oxidase containing only two electrons per enzyme molecule, which formally corresponds to the reduction of O2 to peroxide. However, more recent examination by kinetic resonance Raman spectroscopy (264) and mass spectrometry (265) clearly demonstrated that the oxygen-oxygen bond is already broken and that hemeo3 is in the oxoferryl state (Feo34+=O) with another oxygen atom being bound to CuB as a hydroxide ion. The “peroxy” state can also be generated directly in the reaction of the oxidizedbo3 with H2O2 (266), and the resulting spectrum has a characteristic peak at 582 nm and a shoulder at 550 nm.

Upon the arrival of the next electron and the proton, the “peroxy” form (30) is converted into a ferryl intermediate. The results of time-resolved resonance Raman studies showed the formation of a ferryl intermediate with a rate constant of about 2 × 104 s−1 (267,268). A very similar rate was also detected by visible spectroscopy (30,269,270). The stable ferryl intermediate can be obtained as the end product in the reaction of the fully reduced enzyme with oxygen when no bound ubiquinone is in the QH site (269). Such an enzyme contains only three of the four electrons required for complete O2 reduction, and so the catalytic cycle stalls at the ferryl state. In the visible spectroscopy, this state is characterized by a spectrum with peaks at 557 and about 420 nm.

The presence of bound ubiquinone at the QH site of cytochromebo3 (150) increases the electron capacitance of the enzyme and allows the reaction to proceed further to yield the oxidized form. The rate of formation of the oxidized state in the single-turnover experiments was estimated to be 0.3 × 103 s−1 by recording the electron and proton transfer reactions (271).

Mechanism of ΔμH+ formation by cytochromebo3

The oxidation of ubiquinol (Em of redox couple Q/QH2 ∼ +0.1 V) by oxygen (Em of redox couple O2/H2O ∼ +0.8 V) is linked with free energy release in the order of ∼0.7 V. The proton motive force created by the respiratory chain on theE. coli cellular membrane is about −0.2 V (272,273). It is clear that excess free energy (∼0.5 V) can be used for the translocation of more than one charge across the membrane. Indeed, measurement of the stoichiometry (28) of the proton transfer by thebo3 oxidase on theE. coli cellular membrane showed that two protons are transferred per each electron used for the O2 reduction. Of these two charges, the first is driven by the vectorial chemistry and the second is driven by the proton pump (240). The vectorial chemistry includes the oxidation of the ubiquinol molecule and the reduction of dioxygen, with the release and uptake, respectively, of one proton per electron. The charge separation in this case is achieved by the separation in the space of these two events.