Explore more from Afghanistan

Third Afghan War and the Revolt in Waziristan

7 minute read

2nd Battalion 5th Gurkha Rifles at Ahnai Tangi in Waziristan, 14 January 1920

A treaty broken

In February 1919, Amanullah Khan became the new Amir of Afghanistan. He immediately repudiated the Treaty of Gandamak, which had given the British control of Afghan foreign policy at the end of theSecond Afghan War (1878-80).

Within weeks of his succession, the Amir declared full independence and proclaimed ‘jihad’, or Holy War. By encouraging revolt on the neighbouringNorth-West Frontier of India, he hoped to seize Peshawar and the old Afghan provinces west of the River Indus that had been captured by the Sikhs many years before.

Map of Afghanistan and the North West Frontier, 1919

In the immediate aftermath of theFirst World War (1914-18), Amanullah believed that the British and Indian troops would be too war-weary to resist. He also hoped to take advantage of ongoing nationalist unrest in India, which he himself had done much to encourage. Detachments of Afghan troops entered British India on 3 May 1919.

British troops at Jatta Post in the Khyber, 1919

Indian Army picquet overlooking the Khyber Pass, 1919

British response

Unnerved by Amanullah’s alliance with the new Bolshevik regime in Russia - Britain's traditional rival in the region - and angered by his support for nationalist agitators, the British mobilised their forces.

Sporadic fighting occurred in the tribal districts of Chitral in the far north, but this was successfully contained. Instead, the fighting on the ground focused on the main mountain passes between British India and Afghanistan.

The British ropeway supply system, Landi Kotal in the Khyber, 1919

British soldiers escort Afghan prisoners, 1919

Khyber Pass

Although there was a shortage of men, artillery and machine guns, a division from Peshawar quickly defeated a larger Afghan force that had occupied Bagh and attacked Landi Kotal at the western end of the Khyber Pass. They forced the Afghans back across the border towards Jalalabad, occupying Dakka on 13 May 1919.

At Dakka, the British camp was poorly sited for defence and soon came under attack from Afghan artillery. The Afghans then launched an infantry assault, but this was defeated. The British launched a counter-attack the following day. But it was not until 17 May that the area was properly secured.

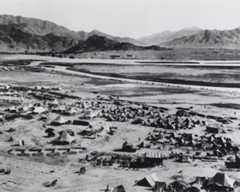

The British camp at Dakka, 1919

British reinforcements at Ali Masjid, mid-way in the Khyber, 1919

Baluchistan

On 27 May 1919, the British successfully stormed the Afghan fortress of Spin Baldak in southern Baluchistan. The fort guarded the strategically vital road from Kandahar to Quetta. Its capture reduced the chance of an Afghan invasion by that route.

Over 200 of its 500-strong garrison of Afghan regulars, many of whom were armed only with single shot Martini-Henry rifles, were killed in the action. The British lost 18 killed and 40 wounded.

The Afghan fort of Spin Baldak after its capture, 1919

The British post at Wana in Waziristan, c1919

Kurram and Waziristan

The largest Afghan attack took place in the Tochi-Kurram valley area. The situation there became critical when the militia in adjacent Waziristan, stirred up by the Afghan government, mutinied against their British employers.

Major Guy Hamilton Russell, commander of the South Waziristan Militia, made a fighting withdrawal with 300 loyal men from Wana to Fort Sandeman between 26 and 30 May 1919. During their retreat, they sustained 40 men killed and wounded. Of the eight British officers, five were killed and two (including Russell) were wounded.

Meanwhile, the garrison at Thal, which guarded the Kurram Pass, was soon cut off and besieged by a large Afghan force under the command of General Nadir Khan. The garrison, consisting of four under-strength battalions of Sikhs and Gurkhas and a squadron of cavalry, held out for a week until relieved by a column from Peshawar under Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer.

The previous month, Dyer had notoriously ordered his men to open fire on nationalist demonstrators at Amritsar in the Punjab.

Colonel Guy Hamilton Russell, 1930

Soldiers at Thal Fort in the Kurram, c1919

The retreat from Wana

Listen to an actor reading from Major Guy Hamilton Russell's 1919 diary.

Airpower on the frontier, 1919

A British airfield on the frontier, c1919

Bombing raids

Airpower played a key role during the war. Five Royal Air Force squadrons of BE2Cs, Bristol F2Bs, De Haviland DH9As and De Haviland DH-bombers were used in strafing and bombing attacks on the rebellious frontier tribes and on targets in Afghanistan itself, including Kabul and Jalalabad.

The attacks on Afghan towns, although small in scale, helped bring King Amanullah to the negotiating table.

Arrival of the Afghan peace delegates at Dakka, 24 July 1919

The Afghan peace delegates at Murree, 1919

Ceasefire

Amanullah Khan ordered a ceasefire on 3 June 1919. His ambitious plans to reclaim Peshawar and throw the British out of India had failed.

But the Treaty of Rawalpindi (8 August 1919) that brought the war to an end did recognise full Afghan independence and finally gave the Afghans the right to conduct their own foreign affairs. This had probably been Amanullah’s real goal.

For the British, the Durand Line, long a contentious issue between the two nations, was reaffirmed as the political boundary separating Afghanistan from the North West Frontier. The Afghans also agreed to stop interfering with the tribes on the British side of the line.

British-Indian battle casualties in the conflict were around 250 men killed and 650 wounded. There were also nearly 1,000 deaths caused by disease.

A Mahsud tribesmen, c1919

Demolishing Nai Kuch village in Waziristan, 1919

Revolt in Waziristan

Neither Afghan Amirs nor British governments had ever really controlled the fiercely independent tribes in the mountainous borderlands between Afghanistan and India. Between 1880 and 1919, the British mounted dozens of operations topunish hill tribes who raided lowland villages. But the cycle of violence continued.

Immediately after the Third Afghan War, Wazir and Mahsud tribes launched attacks on British convoys and posts. Fearsome warriors, they were always on the look-out for opportunities to loot and pillage. They were also angered by false rumours that Waziristan was to be handed over to Afghanistan in post-war talks.

A Waziri tribesman, c1919

A frontier blockhouse at Jandola in Waziristan, c1920

Arms

The tribesmen benefitted greatly from weapons supplied by the Afghans. They also used the guns and ammunition left behind following the ceasefire. Tribal numbers were boosted by many militia deserters.

Highly mobile, and fine shots, the tribesmen were perfectly adapted to their mountainous homeland. Only the most experienced and well-trained British and Indian units could match the Waziris and Mahsuds in frontier fighting.

7th (Bengal) Mountain Battery at Kaniguram, Waziristan, 1920

Armoured cars setting out on reconnaissance, Waziristan, 1919

New frontier policy

Although there was much heavy fighting on the ground, it was the British bombing of Wazir and Mahsud villages that brought the conflict to an end in 1920. Nevertheless, over 10,000 troops from the Indian Army took part in the campaign to re-establish British control of the border areas. Over 1,300 men were killed in action or died from their wounds and sickness.

The difficulties they experienced made the British change their policy on the North West Frontier. Until 1947, Waziristan was permanently garrisoned with experienced regular troops, who worked closely with local militia units.

In 1922-23, a self-contained cantonment, capable of holding 10,000 men, was established at Razmak in Waziristan. The force there included the Razmak Movable Column (RAZCOL), consisting of a strong all-arms brigade with pack transport, that could quickly patrol the surrounding region.

The British also embarked on a road-building programme to improve military access to the most unruly tribal areas.

Jirgah (council) of Mahsuds near Kaniguram, Waziristan, 1920

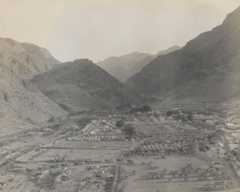

The Razmak Movable Column camp at Sorarogha, 1926

Explore further

First Afghan War

Between 1839 and 1842, British imperial forces fought a bitter war in Afghanistan. Initially successful, the British eventually withdrew having suffered one of the worst military disasters of the 19th century.

Second Afghan War

Between 1878 and 1880, British-Indian forces fought a war to ensure that Afghanistan remained free from Russian interference. Although eventually successful, the British suffered several setbacks in their struggle to control the volatile country.

War in Afghanistan

Britain's most recent war in Afghanistan began in the wake of the '9/11' terrorist attacks on the United States. It continued for 13 years with the last combat troops leaving the country on 26 October 2014.

Independence and Partition, 1947

The birth of India and Pakistan as independent states in 1947 was a key moment in the history of Britain’s empire and its army. But the process of partition was attended by mass migration and ethnic violence that has left a bitter legacy to this day.

The North-West Frontier

Between 1849 and 1947, British and Indian soldiers undertook a series of punitive expeditions against the fiercely independent tribesmen of this wild and mountainous region.

Frederick Roberts: Bobs

Field Marshal Frederick Sleigh Roberts was one of Britain’s most successful military commanders of the 19th century, winning victories during the Second Afghan War and revitalising the British campaign in the Boer War.