Carol Reed was the second son of stage actor, dramatics teacher andimpresario founder of the Royal School of Dramatic Art SirHerbert Beerbohm Tree. Reed was one of Tree's six illegitimate children withBeatrice Mae Pinney, who Tree established in a second household apartfrom his married life. There were no social scars here; Reed grew up ina well-mannered, middle-class atmosphere. His public school days wereat King's School, Canterbury, and he was only too glad to push on withthe idea of following his father and becoming an actor. His mother wanted nosuch thing and shipped him off to Massachusetts in 1922, where hisolder brother resided on--of all things--a chicken ranch.

It was a wasted six months before Reed was back in England and joined astage company of DameSybil Thorndike,making his stage debut in 1924. He forthwith met British writerEdgar Wallace, who cashed in on hisconstant output of thrillers by establishing a road troupe to do stageadaptations of them. Reed was in three of these, also working as anassistant stage manager. Wallace became chairman of the newly formedBritish Lion Film Corp. in 1927, and Reed followed to become hispersonal assistant. As such he began learning the film trade byassisting in supervising the filmed adaptations of Wallace's works.This was essentially his day job. At night he continued stage actingand managing. It was something of a relief when Wallace passed on in1932; Reed decided to drop the stage for film and joined historicEaling Studios as dialog director for Associated Talking Pictures underBasil Dean.

Reed rose from dialog director to second-unit director and assistantdirector in record time, his first solo directorship being theadventureMidshipman Easy (1935).This and his subsequent effort,Laburnum Grove (1936), attractedhigh praise from a future collaborator, novelist/criticGraham Greene, who said that onceReed "gets the right script, [he] will prove far more than efficient."However, Reed would endure the sort of staid, boilerplate filmmakingthat characterized British "B" movies until he left this behind withThe Stars Look Down (1940),his second film withMichael Redgrave,and his openly HitchcockianNight Train to Munich (1940),a comedy-thriller withRex Harrison. It has often beenseen as a sequel toAlfred Hitchcock'sThe Lady Vanishes (1938) withthe same screenwriters and comedy relief--Basil Radford andNaunton Wayne, who would just about makecareers as the cricket zealots Charters and Caldicott, from "Vanishes".

The British liked these films and, significantly, so did America, whereHollywood still wondered whether their patronage of the British filmindustry was worth the gamble of a payoff via the US public. Dean wasjust one of several powerhouse producers rising in Britain in the1930s. Other names are more familiar:Alexander Korda andJ. Arthur Rank stand out. For Reed, whowould wisely decide to start producing his own films in order to havemore control over them, finding his niche was still a challenge intothe 1940s. He was only too well aware that the film director led a teameffort--his was partly a coordinator's task, harmonizing the talents ofthe creative team. The modest Reed would admit to his success beingthis partnership time and again. So he gravitated toward the samescriptwriters, art directors and cinematographers as his movie listspread out.

There were more thrillers and some historical bios:Kipps (1941) with Redgrave andThe Young Mr. Pitt (1942) withRobert Donat. He did service and war effortfare through World War II, but these were more than flag wavers, forReed dealt with the psychology of transitioning to military life. HisAnglo-American documentary of combat (co-directed byGarson Kanin),The True Glory (1945), won the1946 Oscar for Best Documentary. With that under his belt, Reed was nowrecognized as Britain's ablest director and could pick and choose hisprojects. He also had the clout--and the all-important funds--to dowhat he thought was essential to ensure realism on a location shoot,something missing in British film work prior to Reed.

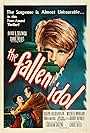

Odd Man Out (1947) withJames Mason as an IRA hit man on therun did just that and was Reed's first real independent effort, and hehad gone to Rank to do it. All too soon, however, that organizationbegan subjugating directors' wishes to studio needs, and Reed madeperhaps his most important associative decision and joined Korda'sLondon Films. Here was one very important harmony--he and Korda thoughtalong the same lines. ThoughAnthony Kimmins had scripted four filmsfor Reed, it was time for Korda to introduce the director toGraham Greene. Their associationwould bring Reed his greatest successes.The Fallen Idol (1948) was basedon a Greene short story, withRalph Richardson as ado-everything head butler in a diplomatic household. Idolized by thelonely, small son of his employer, he becomes caught up in a liaisonwith a woman on the work staff, who was much younger than his shrewishwife. It may seem slow to an American audience, but with the focus onthe boy's wide-eyed view of rather gloomy surroundings, as well as theadult drama around him, it was innovative and a solid success.

What came next was a landmark--the best known of Reed's films.Daisan no otoko (1949) was yetanother Greene story, molded into a gem of a screenplay by him, thoughReed added some significant elements of his own. The film has beenendlessly summarized and analyzed and, whether defined as aninternational noir or post-war noir or just noir, it was cutting-edgenoir and unforgettable. This was Reed in full control--well, almost--and the money was coming from yet another wide-vision producer,David O. Selznick, along with Korda.Tension did develop in this effort keep a predominantly Anglo effort inthis Anglo-American collaboration.

There were complications, though. For one thing, Korda--old friend andsomewhat kindred spirit of wunderkind directorOrson Welles--had a gentlemen's agreementwith the latter for three pictures, but these were not forthcoming.Korda could be as evasive as Welles was known to be, and Welles hadcome to Europe to further his inevitable film projects after troublesin Hollywood. Always desperate for seed money, Welles was forced totake acting parts in Europe to build up his bank account in order tofinance his more personal projects. He thus accepted the role of thelarger-than-life American flim-flam man turned criminal, Harry Lime.The extended time spent filming the Vienna sewer scenes on location andat the elaborate set for them at Shepperton Studios in London, entailedthe longest of the ten minutes or so of Welles' screen time. Here was apotential source of directorial intimidation if ever there was one.Welles took it upon himself to direct Reed's veteran cinematographerRobert Krasker with his own vision ofsome sewer sequences in London (after leaving the location shoot inVienna), using many takes. Supposedly, Reed did not use any of Welles'footage, and in fact whatever there was got conveniently lost. YetShimin Kein (1941)'s shadow was solooming that Welles was given credit for a lot of camera work,atmospherics and the chase scenes. He had referred to the movie as "myfilm" later on and had said he wrote all his dialog. Some of the ferriswheel dialog with its famous famous "cuckoo clock" speech (which Reedand Greene both attributed to him) was probably the essence of Welles'contributions.

Krasker's quirky angles under Reed's direction perfectly framed theready-made-for-an-art designer bombed-out shadows and stark, isolatedstreet lights of postwar Vienna and its underworld. Unique to cinemahistory, the whole score (except for some canned incidental café music) wasjust the brilliant zither playing ofAnton Karas, adding his nuances to everydramatic transition. Krasker won an Oscar, and Karas was nominated for one.

Reed's attention to detailed casting also paid off, particularly incasting German-speaking actors and background players. Selznickinsisted onJoseph Cotten as HollyMartins, the benighted protagonist, and his clipped and sharp voice andsubterranean drawl were perfect for the part. Reed had wantedJames Stewart--definitely adifferent perception than Americans of its leading men. Selznick partedways with Reed on other issues, however; there was a laundry list ofreasons for his re-editing and changing some incidentals for theshorter American version, partly based on negative comments from sneakpreview responses. Perhaps it was the constant interruptions from theother side of the Atlantic that drove Reed to personally narrate theintroduction describing Martins in the British version of the film(given the basic tenets of noir films, the star always played narratorto introduce the story and voice over where appropriate). Selznickshowed himself--in this instance, anyway--to have a better directorialsense by substituting Cotten introducing himself in the American cut.It made far more sense and was much more effective. On the other hand,Selznick's editing of the pivotal railway café scenes with Cotten andAlida Valli had continuity problems.

Nonetheless, the film was an international smash, and all the principalplayers reaped the rewards. Reed did not get an Oscar, but he did winthe Cannes Film Grand Prix. Greene was motivated enough to take thestory and expand it into a best-selling novel. Even Welles, with hisminimum screen time--he was spending most of his time in Europetrying to obtain financing for his newest project,Otello (1956)--milked the movie for all itwas worth. He did not deny directorial influences (though in a 1984interview he did), and even developed a Harry Lime radio show backhome.

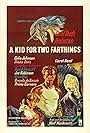

However, the movie had its detractors. It was called too melodramaticand too cynical. The short scenes of untranslated German dialog werealso criticized, yet that lent to the atmosphere of confusion andhelplessness of Martins caught in a wary, potentially dangerousenvironment--something the audience inevitably was able to share. Itwas all too ironic that Reed, now declared by some as the greatestliving director of the time, found his career in decline thereafter. Ofhis total output, four were based on plays, three on stories and 15 onnovels. With less than half of them to go, he was to be disappointedfor the most part. HisThe Man Between (1953) with JamesMason was too much of a "Third Man" reprise, andA Kid for Two Farthings (1955)was too sentimental.

By now Reed was being sought by enterprising Hollywood producers. Hehad--as he usually did--the material for a first-rate movie with twopopular American actors,Burt LancasterandTony Curtis forKûchû buranko (1956). However, it suffered froma slow script, as would the British-producedThe Key (1958), despite anotherinternational cast. Things finally picked up with his venture intoanother Greene-scripted film from his novel, withAlec Guinness in the lead in the UK spyspoofOur Man in Havana (1959)with yet another winning international cast.

When Hollywood called again, the chance at such a British piece ofhistory asMutiny on the Bounty (1962)with a mostly British cast andMarlon Brando seemed bound for success. Itwas the second version of the movie produced by MGM (the first being theClark Gable starrerSenkan Baunti-go no hanran (1935)).However, Brando's history of being temperamental was much in evidenceon location in Tahiti. Reed shot a small part of the picture butfinally left, having more than his fill of the star's ego (and,evidently, being allowed too much artistic control by the studio) andthe film was finished byLewis Milestone. Reed would ultimatelybe branded as a failure in directing historical movies, but it was anunfair appraisal based on the random aspect of film success and suchforces of nature as Brando, not artistic and technical expertise.

The opportunity to make another film came knocking again with Reed andAmerican money forming the production company International Classics toproduceIrving Stone's best-selling storyof Michelangelo and the painting of the Sistine Chapel,The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965).Here is perhaps the prime example of Reed being given short shrift fora really valiant effort at an historical, artistically significant andcultural epic because it was a "flop" at the box office. Shot onlocation in Rome and its environs, the film had a first-rate castheaded byCharlton Heston doing hismethod best as the temperamental artist withRex Harrison, an effortlessstandout as the equally volatile Pope Julius II.Diane Cilento did fine work as theContessina de Medici, with the always stalwartHarry Andrews as architect rival DonatoBramante. Most of the other roles were filled by Italians dubbed inEnglish, but they all look good.

Reed's attention to historical detail provided perhaps the mostaccurate depiction of early 16th-century Italy--from costumes andmanners to military action and weapons (especially firearms)--everbrought to the screen. The script byPhilip Dunne was brisk and alwaysentertaining in the verbal battle between the artist and his pontiff.Yet by the 1960s costume epics were going out of style and biggerflops, such asCleopatra (1963) (talkabout agony) despite the wealth of stars which included Harrison,tended to spread like a disease to those few that came later. Despite ahigh-powered distribution campaign by Twentieth Century-Fox, Reed'sexemplary effort would ultimately be appreciated by art scholars andhistorians--not the stuff of Hollywood's money mentality.

For Reed the only remaining triumph was, of all things, a musical--hisfirst and only--yet again he was working with children. However, theadaptation of the greatCharles Dickensnovel "Oliver Twistt" top the screen (asOliver! (1968)) was asensation with a lively script and music amid a realistic 19th-centuryLondon that was up to Reed's usual standards. The film was nominatedfor no less than 11 Oscars, wining five and two of the big ones--BestPicture and Best Director. Reed had finally achieved that bit ofelusiveness. He could never be so simplistically stamped with an unevencareer; Reed had always kept to a precise craftsman's movie-makingformula.

Fellow British directorMichael Powell had said that Reed"could put a film together like a watchmaker puts together a watch". Itwas Graham Greene, however, who gave Reed perhaps the more importantpersonal accolade: "The only director I know with that particularwarmth of human sympathy, the extraordinary feeling for the right facein the right part, the exactitude of cutting, and not least importantthe power of sympathizing with an author's worries and an ability toguide him."

It was a wasted six months before Reed was back in England and joined astage company of DameSybil Thorndike,making his stage debut in 1924. He forthwith met British writerEdgar Wallace, who cashed in on hisconstant output of thrillers by establishing a road troupe to do stageadaptations of them. Reed was in three of these, also working as anassistant stage manager. Wallace became chairman of the newly formedBritish Lion Film Corp. in 1927, and Reed followed to become hispersonal assistant. As such he began learning the film trade byassisting in supervising the filmed adaptations of Wallace's works.This was essentially his day job. At night he continued stage actingand managing. It was something of a relief when Wallace passed on in1932; Reed decided to drop the stage for film and joined historicEaling Studios as dialog director for Associated Talking Pictures underBasil Dean.

Reed rose from dialog director to second-unit director and assistantdirector in record time, his first solo directorship being theadventureMidshipman Easy (1935).This and his subsequent effort,Laburnum Grove (1936), attractedhigh praise from a future collaborator, novelist/criticGraham Greene, who said that onceReed "gets the right script, [he] will prove far more than efficient."However, Reed would endure the sort of staid, boilerplate filmmakingthat characterized British "B" movies until he left this behind withThe Stars Look Down (1940),his second film withMichael Redgrave,and his openly HitchcockianNight Train to Munich (1940),a comedy-thriller withRex Harrison. It has often beenseen as a sequel toAlfred Hitchcock'sThe Lady Vanishes (1938) withthe same screenwriters and comedy relief--Basil Radford andNaunton Wayne, who would just about makecareers as the cricket zealots Charters and Caldicott, from "Vanishes".

The British liked these films and, significantly, so did America, whereHollywood still wondered whether their patronage of the British filmindustry was worth the gamble of a payoff via the US public. Dean wasjust one of several powerhouse producers rising in Britain in the1930s. Other names are more familiar:Alexander Korda andJ. Arthur Rank stand out. For Reed, whowould wisely decide to start producing his own films in order to havemore control over them, finding his niche was still a challenge intothe 1940s. He was only too well aware that the film director led a teameffort--his was partly a coordinator's task, harmonizing the talents ofthe creative team. The modest Reed would admit to his success beingthis partnership time and again. So he gravitated toward the samescriptwriters, art directors and cinematographers as his movie listspread out.

There were more thrillers and some historical bios:Kipps (1941) with Redgrave andThe Young Mr. Pitt (1942) withRobert Donat. He did service and war effortfare through World War II, but these were more than flag wavers, forReed dealt with the psychology of transitioning to military life. HisAnglo-American documentary of combat (co-directed byGarson Kanin),The True Glory (1945), won the1946 Oscar for Best Documentary. With that under his belt, Reed was nowrecognized as Britain's ablest director and could pick and choose hisprojects. He also had the clout--and the all-important funds--to dowhat he thought was essential to ensure realism on a location shoot,something missing in British film work prior to Reed.

Odd Man Out (1947) withJames Mason as an IRA hit man on therun did just that and was Reed's first real independent effort, and hehad gone to Rank to do it. All too soon, however, that organizationbegan subjugating directors' wishes to studio needs, and Reed madeperhaps his most important associative decision and joined Korda'sLondon Films. Here was one very important harmony--he and Korda thoughtalong the same lines. ThoughAnthony Kimmins had scripted four filmsfor Reed, it was time for Korda to introduce the director toGraham Greene. Their associationwould bring Reed his greatest successes.The Fallen Idol (1948) was basedon a Greene short story, withRalph Richardson as ado-everything head butler in a diplomatic household. Idolized by thelonely, small son of his employer, he becomes caught up in a liaisonwith a woman on the work staff, who was much younger than his shrewishwife. It may seem slow to an American audience, but with the focus onthe boy's wide-eyed view of rather gloomy surroundings, as well as theadult drama around him, it was innovative and a solid success.

What came next was a landmark--the best known of Reed's films.Daisan no otoko (1949) was yetanother Greene story, molded into a gem of a screenplay by him, thoughReed added some significant elements of his own. The film has beenendlessly summarized and analyzed and, whether defined as aninternational noir or post-war noir or just noir, it was cutting-edgenoir and unforgettable. This was Reed in full control--well, almost--and the money was coming from yet another wide-vision producer,David O. Selznick, along with Korda.Tension did develop in this effort keep a predominantly Anglo effort inthis Anglo-American collaboration.

There were complications, though. For one thing, Korda--old friend andsomewhat kindred spirit of wunderkind directorOrson Welles--had a gentlemen's agreementwith the latter for three pictures, but these were not forthcoming.Korda could be as evasive as Welles was known to be, and Welles hadcome to Europe to further his inevitable film projects after troublesin Hollywood. Always desperate for seed money, Welles was forced totake acting parts in Europe to build up his bank account in order tofinance his more personal projects. He thus accepted the role of thelarger-than-life American flim-flam man turned criminal, Harry Lime.The extended time spent filming the Vienna sewer scenes on location andat the elaborate set for them at Shepperton Studios in London, entailedthe longest of the ten minutes or so of Welles' screen time. Here was apotential source of directorial intimidation if ever there was one.Welles took it upon himself to direct Reed's veteran cinematographerRobert Krasker with his own vision ofsome sewer sequences in London (after leaving the location shoot inVienna), using many takes. Supposedly, Reed did not use any of Welles'footage, and in fact whatever there was got conveniently lost. YetShimin Kein (1941)'s shadow was solooming that Welles was given credit for a lot of camera work,atmospherics and the chase scenes. He had referred to the movie as "myfilm" later on and had said he wrote all his dialog. Some of the ferriswheel dialog with its famous famous "cuckoo clock" speech (which Reedand Greene both attributed to him) was probably the essence of Welles'contributions.

Krasker's quirky angles under Reed's direction perfectly framed theready-made-for-an-art designer bombed-out shadows and stark, isolatedstreet lights of postwar Vienna and its underworld. Unique to cinemahistory, the whole score (except for some canned incidental café music) wasjust the brilliant zither playing ofAnton Karas, adding his nuances to everydramatic transition. Krasker won an Oscar, and Karas was nominated for one.

Reed's attention to detailed casting also paid off, particularly incasting German-speaking actors and background players. Selznickinsisted onJoseph Cotten as HollyMartins, the benighted protagonist, and his clipped and sharp voice andsubterranean drawl were perfect for the part. Reed had wantedJames Stewart--definitely adifferent perception than Americans of its leading men. Selznick partedways with Reed on other issues, however; there was a laundry list ofreasons for his re-editing and changing some incidentals for theshorter American version, partly based on negative comments from sneakpreview responses. Perhaps it was the constant interruptions from theother side of the Atlantic that drove Reed to personally narrate theintroduction describing Martins in the British version of the film(given the basic tenets of noir films, the star always played narratorto introduce the story and voice over where appropriate). Selznickshowed himself--in this instance, anyway--to have a better directorialsense by substituting Cotten introducing himself in the American cut.It made far more sense and was much more effective. On the other hand,Selznick's editing of the pivotal railway café scenes with Cotten andAlida Valli had continuity problems.

Nonetheless, the film was an international smash, and all the principalplayers reaped the rewards. Reed did not get an Oscar, but he did winthe Cannes Film Grand Prix. Greene was motivated enough to take thestory and expand it into a best-selling novel. Even Welles, with hisminimum screen time--he was spending most of his time in Europetrying to obtain financing for his newest project,Otello (1956)--milked the movie for all itwas worth. He did not deny directorial influences (though in a 1984interview he did), and even developed a Harry Lime radio show backhome.

However, the movie had its detractors. It was called too melodramaticand too cynical. The short scenes of untranslated German dialog werealso criticized, yet that lent to the atmosphere of confusion andhelplessness of Martins caught in a wary, potentially dangerousenvironment--something the audience inevitably was able to share. Itwas all too ironic that Reed, now declared by some as the greatestliving director of the time, found his career in decline thereafter. Ofhis total output, four were based on plays, three on stories and 15 onnovels. With less than half of them to go, he was to be disappointedfor the most part. HisThe Man Between (1953) with JamesMason was too much of a "Third Man" reprise, andA Kid for Two Farthings (1955)was too sentimental.

By now Reed was being sought by enterprising Hollywood producers. Hehad--as he usually did--the material for a first-rate movie with twopopular American actors,Burt LancasterandTony Curtis forKûchû buranko (1956). However, it suffered froma slow script, as would the British-producedThe Key (1958), despite anotherinternational cast. Things finally picked up with his venture intoanother Greene-scripted film from his novel, withAlec Guinness in the lead in the UK spyspoofOur Man in Havana (1959)with yet another winning international cast.

When Hollywood called again, the chance at such a British piece ofhistory asMutiny on the Bounty (1962)with a mostly British cast andMarlon Brando seemed bound for success. Itwas the second version of the movie produced by MGM (the first being theClark Gable starrerSenkan Baunti-go no hanran (1935)).However, Brando's history of being temperamental was much in evidenceon location in Tahiti. Reed shot a small part of the picture butfinally left, having more than his fill of the star's ego (and,evidently, being allowed too much artistic control by the studio) andthe film was finished byLewis Milestone. Reed would ultimatelybe branded as a failure in directing historical movies, but it was anunfair appraisal based on the random aspect of film success and suchforces of nature as Brando, not artistic and technical expertise.

The opportunity to make another film came knocking again with Reed andAmerican money forming the production company International Classics toproduceIrving Stone's best-selling storyof Michelangelo and the painting of the Sistine Chapel,The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965).Here is perhaps the prime example of Reed being given short shrift fora really valiant effort at an historical, artistically significant andcultural epic because it was a "flop" at the box office. Shot onlocation in Rome and its environs, the film had a first-rate castheaded byCharlton Heston doing hismethod best as the temperamental artist withRex Harrison, an effortlessstandout as the equally volatile Pope Julius II.Diane Cilento did fine work as theContessina de Medici, with the always stalwartHarry Andrews as architect rival DonatoBramante. Most of the other roles were filled by Italians dubbed inEnglish, but they all look good.

Reed's attention to historical detail provided perhaps the mostaccurate depiction of early 16th-century Italy--from costumes andmanners to military action and weapons (especially firearms)--everbrought to the screen. The script byPhilip Dunne was brisk and alwaysentertaining in the verbal battle between the artist and his pontiff.Yet by the 1960s costume epics were going out of style and biggerflops, such asCleopatra (1963) (talkabout agony) despite the wealth of stars which included Harrison,tended to spread like a disease to those few that came later. Despite ahigh-powered distribution campaign by Twentieth Century-Fox, Reed'sexemplary effort would ultimately be appreciated by art scholars andhistorians--not the stuff of Hollywood's money mentality.

For Reed the only remaining triumph was, of all things, a musical--hisfirst and only--yet again he was working with children. However, theadaptation of the greatCharles Dickensnovel "Oliver Twistt" top the screen (asOliver! (1968)) was asensation with a lively script and music amid a realistic 19th-centuryLondon that was up to Reed's usual standards. The film was nominatedfor no less than 11 Oscars, wining five and two of the big ones--BestPicture and Best Director. Reed had finally achieved that bit ofelusiveness. He could never be so simplistically stamped with an unevencareer; Reed had always kept to a precise craftsman's movie-makingformula.

Fellow British directorMichael Powell had said that Reed"could put a film together like a watchmaker puts together a watch". Itwas Graham Greene, however, who gave Reed perhaps the more importantpersonal accolade: "The only director I know with that particularwarmth of human sympathy, the extraordinary feeling for the right facein the right part, the exactitude of cutting, and not least importantthe power of sympathizing with an author's worries and an ability toguide him."

BornDecember 30, 1906

DiedApril 25, 1976(69)

- Won 1 Oscar

- 6 wins & 15 nominations total

Director

Producer

Second Unit or Assistant Director

- Alternative name

- Sir Carol Reed

- Height

- 1.88 m

- Born

- Died

- April 25,1976

- Chelsea, London, England, UK(heart attack)

- SpousesPenelope Dudley-WardJanuary 24, 1948 - April 25, 1976 (his death, 1 child)

- Relatives

- Oliver Reed(Niece or Nephew)

- Other worksstage: spear carrier in George Bernard Shaw's "Saint Joan" with Sybil Thorndike and a young Laurence Olivier

- Publicity listings

- TriviaUncle ofOliver Reed.

- QuotesTo be any good to a director an actor must either be wonderful, or know nothing about acting. A little knowledge--that's what is bad.

- TrademarksTilted camera angles at moments of suspense or uneasiness

- Salary

- (1958)$150 000

FAQ

Powered by Alexa

- When did Carol Reed die?April 25, 1976

- How did Carol Reed die?Heart attack

- How old was Carol Reed when he died?69 years old

- Where did Carol Reed die?Chelsea, London, England, UK

- When was Carol Reed born?December 30, 1906

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content