William Goetz, a producer and studio boss who revolutionized theindustry with the development of the profit participation deal, wasborn on 3/24/1903 in Philadelphia, PA, to ship's purserTheodore Goetz and his wife Fanny. William was the youngest in a broodof eight children (six boys and two girls). After Fanny's death in 1913Theodore abandoned his family, and William was raised by his olderbrothers.

All of the Goetz brothers wound up in the movie business. Two of hisbrothers worked at Monogram and were among the founders of RepublicPictures (seeHerbert J. Yates), andanother worked forCorinne GriffithProductions. In 1924 Goetz took advantage of the well-known Hollywoodpractice of nepotism and moved to Hollywood where his brothers got hima job at Corinne Griffith Productions as a crew member. Within threeyears he had worked his way up to associate producer. Goetz then movedon to production jobs at MGM and Paramount before becoming an associateproducer at Fox Films in March 1930. The first movies Goetz produced atFox were two Spanish-language westerns,El último de los Vargas (1930),based on aZane Grey novel, andFigaro e la sua gran giornata (1931),both of which starredGeorge J. Lewis as"Jorge Lewis."

A dashing man with an earthy sense of humor, Goetz marriedLouis B. Mayer's daughter Edith in 1930.Edith said her husband was a fast talker who persistently telephonedher for a date after they met at Los Angeles' Ambassador Hotel. When Goetzasked Edith to marry him Mayer objected, wanting to know how he wasgoing to support her. Goetz won Mayer's consent when he replied, "Ifnecessary, Mr. Mayer, with my own two hands." The two men wouldcontinue to argue about the proposed marriage right up until theceremony itself. Their marriage was Hollywood's wedding of the year.William and Edith's marriage lasted until his death, and they had twodaughters. His ultra-conservative father-in-law would eventuallydisinherit Edith, perhaps because of his son-in-law's key role inundermining the studio system in the 1950s, or because he was a staunchDemocrat, or possibly due to the brothers' ties to a man with reputedunderworld connections (although Mayer's ostensible bossNicholas M. Schenck, Chairman of Loew's Inc. had the same connections).

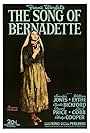

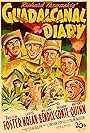

One of the most influential figures in Goetz's life would prove to beWarner Bros.' production chiefDarryl F. Zanuck, who had remarkablyrisen through the ranks of Hollywood on his own merits and who had anatural disdain for nepotism. Nearly every one of Warner Bros.'successes after 1924 could be directly credited to the workaholic (manywould add sexoholic) producer-writer-production chief. In 1933 Zanuckhad quit Warners after a long-simmering rift withHarry M. Warner. Despite being offeredseveral positions at other studios, Zanuck had a burning desire to runhis own studio and was approached by the affableJoseph M. Schenck with an offer thatwould result in the creation of Twentieth Century Pictures. The dealwas a conglomeration of backers, each with his own agenda, but eachhaving enormous confidence in Zanuck's enviable track record ofdelivering a prodigious number of hits. Twentieth Century Pictures wascreated as a partnership betweenLouis B. Mayer, former United ArtistspresidentJoseph M. Schenck and Loew's Inc. (the parent company of MGM)head Nicholas Schenck (Joe's brother and officially Mayer's boss), whoarranged for underwriting by the Bank of America with additionalbacking by the cunningly abrasiveHerbert J. Yates, who keenly sought outguaranteed business for his Consolidated Film Labs (and who would soonform Republic Pictures out of a merger among Mascot Pictures, MonogramPictures and Liberty Pictures when bankrupt producerMack Sennett's studio became available).Goetz's involvement was based on a string Mayer attached for his money:he wanted his son-in-law out from under his thumb. Whatever talentsWilliam Goetz possessed as a young man in Hollywood were lost on hisfather-in-law. Twentieth Century merged with ailing Fox Films (whichowned a desirable theater chain) in 1935, and Goetz was named vicepresident of Twentieth Century-Fox, with Zanuck over him as productionhead and Joe Schenck serving as president. In its infancy the studiorelied heavily on the talents of a small roster of popular stars suchasTyrone Power,Don Ameche andAlice Faye, but found a gold mine in anadorable and monumentally talented six-year-old moppet namedShirley Temple, who literally kept thethe ink from turning red. Among the 20th Century-Fox pictures Goetzpersonally produced wereRothschild (1934),for which he received an Academy Award nomination for Best Picturealong with Zanuck;Les Misérables (1935), a classicHollywood production ofVictor Hugo's novel; and a hitadaptation ofJack London'sThe Call of the Wild (1935),which starred MGM loan-outClark Gable,Loretta Young (who got pregnant by Gableduring production) andJack Oakie.Goetz's stock at the studio began to rise and he gained a reputationfor being an efficient, unassuming producer who (most importantly)could bring a project in at or under budget. At the outbreak of WWII,Zanuck eagerly accepted an army commission and placed Goetz as actinghead of the studio in 1942. As production head, Goetz was responsiblefor some prestigious films that brought credit to both him and thestudio, includingGuadalcanal Diary (1943) andtheThe Song of Bernadette (1943),which was nominated for 12 Academy Awards and won four, including aBest Actress Oscar forJennifer Jones, who wouldeventually become the wife of Goetz's then brother-in-law,David O. Selznick.

Like his father-in-law Louis B. Mayer, Goetz emphasized quality todistinguish his product in the market, and he did not flinch fromspending money to achieve it. Unlike Mayer, however, Goetz learned themechanics of bringing a project through to completion. Hollywood is atown where paranoid bosses push many ambitious men out of theirpositions, though, and 20th Century-Fox was no different. Zanuck stillregarded Goetz as an unimaginative administrator and began hearingrumors that Goetz was growing ambitious. Goetz, however, resigned uponZanuck's return in 1943 to avoid any conflict. Zanuck was also said tobe furious that Goetz had turned his special 4:00 p.m. casting couchinterview room into a storage area.

Mayer, belatedly recognizing Goetz's production talents, offered him achance to be the head of MGM's creative development, but Goetz told hiswife that he had to turn her father down, since the first thing hewould have done at MGM was fire Mayer. Zanuck's 1942-43 absence hadgiven Goetz a taste of running a studio, and since there were no jobson offer to become a studio boss, he created International Pictures in1943 with lawyer Leo Spitz, who had been an adviser to Goetz'sbrother-in-law David O. Selznick. One of the great independentproducers, Selznick had produced the most successful movie of all time,Kaze to tomo ni sarinu (1939),which he found impossible to bring to the screen without help fromMayer, given MGM's irreplaceable Rhett Butler: Gable. Like Zanuck adozen years earlier, Goetz opted to strike out on his own withInternational Pictures (Selznick was furious about that name, believingit conflicted with his own Selznick International Pictures).

During its brief life as an independent company, International Picturesproduced ten middling films distributed by United Artists beforemerging with Universal Pictures to create Universal-InternationalPictures in 1945, with Goetz being appointed production chief. As U-Istudio boss, Goetz partnered with British producerJ. Arthur Rank to release Rank'sBritish-produced films in America. A major stockholder, Rank at onepoint tried to take over the studio, but he proved unsuccessful. UnderGoetz's direction, U-I became known for family fare and well-craftedB-pictures, including the long-runningBud Abbott andLou Costello series of comedies, the"Francis the Talking Mule" series and the popular "Ma and Pa Kettle"movies. These would eventually become repetitious and Goetz had noparticular fondness for inane comedies, but they were money in the bankfor U-I.

Goetz participated in the 1946 Waldorf Conference with hisfather-in-law, MGM capo di tutti capi Nicholas Schenck, and other topstudio executives. The conference was a studio boss pow-wow called byMotion Pictures Producers Association President Eric Johnston, who wasin a panic over the so-called "Hollywood Ten", a group of Hollywoodcreative people who were indicted after failing to testify before theHouse Un-American Activities Committee looking for evidence ofCommunist "subversion" in the motion picture industry. It was at theWaldorf Conference that the Hollywood blacklist was devised, with theaim of ridding the industry of any Communistsm real, suspected orimagined. What it did do was rein in the effect of New Dealprogressives who may have proved too radical for the movie moguls'tastes when it came to labor relations.

Some commentators believe the real deal struck at the WaldorfConference was an agreement to break the militants in the craft unionsby tarring them as "Reds". An ancillary part of this deal, as theargument goes, was an agreement to place in control of the unions menwho had strong ties to organized crime, in order for them to offer thebosses sweetheart deals and put an end to the labor unrest thatHollywood experienced as World War II came to a close. The studios hadalready suffered through a 13-week strike the year before.

The strike was launched on March 12, 1945, when the Conference ofStudio Unions (CSU) went out in protest of the studios' delay inrenewing the contract for interior decorators. The strike had beenopposed by IATSE, which had been under the control of the Chicago mobin the 1930s and early 1940s. The studios had surreptitiously called onMafia muscle to attempt to break up the strike. CSU officials werebranded "Reds" and "Communist subversives" and harassed.Ronald Reagan, the future ScreenActors Guild (SAG) president, had volunteered to be an informer againstthe CSU, snitching to the FBI on its activities.

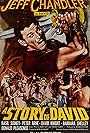

Goetz signed on to the blacklist, perhaps realizing he could notalienate his fellow studio bosses if he was to establishUniversal-International Pictures on a sound footing, as he needed tocurry their favor to get loan-outs of their stars. U-I's major problemwas that it had no box-office stars.Rock Hudson,Tony Curtis andJeff Chandler were contractplayers, but their careers had not yet bloomed. U-I thus had to rely onthe good will of the other studio bosses until it could establishitself as a major player.

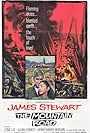

In 1949 Goetz and his good friend, super-agentLew Wasserman, engineered the first profitparticipation deal in motion picture history. U-I wanted Wasserman'sclient,James Stewart, recentlyout of his contract at MGM, to appear inAnthony Mann's new Western,Winchester '73 (1950). Goetz felthe was unable to obtain funds necessary for such a costly production upfront, so he signed Stewart to a deal that gave him half of the profitsof the picture rather than a set fee.

Wasserman had wanted to establish Stewart, an independent contractor,as a corporation to protect him from the then-prohibitive income tax,which topped out at 90% for earners of Stewart's caliber. By making hima producer, Wasserman put Stewart in a lower tax-rate via a productioncompany that would take a tax-favored stake in his movies in lieu of apersonal fee. Stewart's production company would then be taxed at thelower corporate rate.

Stewart netted $750,000 from the deal, with U-I netting the same amount(while the deal cost the studio a greater percentage of profits from ahit, it was also insulated from the losses that possibly could begenerated by a failure, as it lowered production costs). Regardless, itwas a fortuitous deal since the picture was, deservedly, a smash hit. Aprofit participation deal was again used on U-I's excellentStewart-Mann westernBend of the River (1952).

The profit participation deal was revolutionary--- it would ultimatelyunravel the entire studio system, and would soon be copied by otherindependent-minded stars. Many of them would refuse to sign newcontracts with their studios in order to go independent and takeadvantage of percentage deals. It proved to be the straw that finallybroke the studio system's back (having lost proprietary theaterownership in the 1950s was another crippling blow, along with thecompetition from a new medium, television). With profit participationdeals, power shifted from the studios to the stars and their agents.Studios now became financiers and renters of production facilities.

Although U-I shared in the profits of its profit-participationcontracts with Stewart, who became a top-10 box office star for thefirst time in the 1950s appearing in U-I westerns, it did not reverse afinancial slump the studio underwent in the early 1950s. U-I wasfinancially weak and succumbed to a 1952 take-over by Decca Records.

Wasserman's MCA, an entertainment conglomerate that began as a talentagency but thrived as a leading TV producer due to a secret waivergranted it by SAG when it was headed by Wasserman client Ronald Reagan,ultimately would buy U-I by acquiring Decca Records in 1962 (Wassermanand MCA chairmanJules Stein reportedly hadclose ties to the Chicago mob; as late as 1984, a Mafia enforcerbelonging toJohn Gotti's Gambino crimefamily with "a past history of arranging narcotics smuggling,"according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency, was serving as amiddleman for MCA despite having no prior experience in the musicindustry. An investigation into MCA in the mid-'80s was quashed bythen-President Ronald Reagan's Justice Department. Wasserman hadremained close to Reagan, a man he had made a millionaire by giving himan ownership stake in the TV seriesDeath Valley Days (1952)and also through a land deal. Through Wasserman, Reagan had becomewealthy enough to pursue a political career after his acting careerended in 1964. Despite being a liberal Democrat, Wasserman raised moneyfor Reagan's first gubernatorial campaign as a right-wing Republicanand served as the chief fundraiser for his presidential library.

Goetz left the studio in 1954 and went independent, having obtained adistribution deal through Columbia for his William Goetz Productions.Films produced by the independent Goetz were nominated three times forGolden Globes:Sayonara (1957), whichgarnered Academy Award nominations for Goetz, directorJoshua Logan, starMarlon Brando and Best Supporting Oscarsfor featured playersRed Buttons andMiyoshi Umeki;Me and the Colonel (1958), aHolocaust comedy starringDanny Kaye; andSong Without End (1960), amusical about composerFranz Lisztco-directed byGeorge Cukor, which wonGoetz the Best Musical Song from the Hollywood Foreign PressAssociation, and an Oscar for Best Music.

Like many movie moguls, including Nicholas Schenck and hisfather-in-law, Goetz raised thoroughbreds. He bought his first racingstock from L.B, a famous horse breeder who got out of the racingbusiness after World War II, as it was bad for his image. Goetz's horseYour Host won the 1950 Santa Anita Derby and subsequently sired Kelso,one of the all-time money winners.

Goetz terminated his production company in 1961 after making theGlenn Ford service comedyCry for Happy (1961), but he cameout of retirement in 1964 to take the job of vice president at SevenArts Productions Ltd., a Canadian-controlled production anddistribution corporation. Goetz possibly took the job as a favor to hisfriend Lew Wasserman, as the major stockholder in Seven Arts, LouisChesler, had ties to the Chicago mob, as did Wasserman in his earlydays as a musician and recording artists' agent. Significantly, Cheslerhad served on the board of directors of Allied Artists, a subsidiary ofhis brothers' defunct Monogram Pictures.

Chesler, an aficionado of horse-racing like Goetz and a reputedgambler, was the driving force behind Seven Arts Productions, which wascapitalized on Toronto's stock exchange. In addition to investing inthe entertainment field, the 300-pound entrepreneur was a major housingdeveloper in Florida. Chesler was described as a front or associate ofunderworld crime bossesVito Genovese andMeyer Lansky through the Florida realestate company General Development Corp., which he owned with anotherLasky associate, Wallace Groves.

General Development's board of directors included gangster "TriggerMike" Coppola and Max Orovitz, who was Lansky's stockbroker. Anotherpartner wasEddie DeBartolo, a shoppingmall developer and racetrack owner with a taste for high-stakesgambling. DeBartolo, who bought the San Francisco 49ers professionalfootball team for his son,Edward DeBartolo Jr., was close toLansky and Lansky associatesCarlos Marcello, who controlledFlorida's narcotics and gambling, and New Orleans Mafia bossSanto Trafficante Jr.. Both Marcello andTrafficante, who owed fealty to the Chicago mob, had been recruited viaChicago bossSam Giancana to assassinateCuban leaderFidel Castro for theCIA, which they were glad to do, as Castro had booted them and Lanskyout of Cuba--where they controlled lucrative gambling, narcotics,prostitution and other criminal activities--after the 1959 revolution(some conspiracy theorists place the responsibility for PresidentJohn F. Kennedy's assassination onMarcello and Trafficante, though that has never been proven.)

Through General Development Corp., Chesler and Groves introducedgambling to the Bahamas, buying half of Grand Bahama Island and settingup the Grand Bahama Development Co. in the early 1960s to build a hotelcum casino. It was through Chesler that the Bahamian gaming businesswas penetrated by Lansky, looking for a new territory after losingCuba, and Dino Cellini, a mob banker described as Lansky's right-handman, the person he most trusted with the receipts from his gamblingoperations. One of Chesler's partners in the Bahamas was CarrollRosenbloom, owner of the Los Angeles Rams and one of the three largestshareholders in Seven Arts, who was described as a notorious gambler.

Although Chesler is credited with opening up the British crown colonyto gambling, having done most of the schmoozing and covert briberythrough the awarding of "consulting fees" to well-connected politiciansand colonial bureaucrats, he was forced out of the Bahamas in a powerstruggle in 1964. Chesler's story, well known in the 1960s, likely wasone of the inspirations for Michael Corleone's Cuban sojourn andbusiness dealings with Hyman Roth--a character based on MeyerLansky--inGodfather Part II (1974).

Lansky's gang ran the "skim" of Bahamian casino money that wasrepatriated to mob banks in Miami controlled by Cellini, who had towork in London and Rome, as he was persona non grata in Florida and theBahamas. Subsequently, development in the Bahamas hit a downturn andthe Canadian holding company Atlantic Acceptance, a major source ofcapital, went bankrupt in June 1965. The company's $104-million defaulttouched off an international financial scandal. Although Cheslerliquidated the rest of his holdings by the end of 1966, he had put hisstamp on the Bahamas by creating the island's gaming industry andintroducing the Lansky gang to the islands.

In 1967 his company, now called Seven Arts Ltd., acquiredJack L. Warner's controlling interest inWarner Bros. Pictures and other interests, including Warner Bros.Records and Reprise Records (the $84-million price tag of theacquisitions was worth approximately $640 million in 2003 dollars). Thecompany was renamed Warner Bros-Seven Arts. The ambitious studio boughtAtlantic Records for $17 million in stock that same year but, crippledby debt, the company itself was acquired by the conglomerate KinneyNational Services Inc. in 1969, the year of Goetz's death.

One of the major shareholders in Warner Bros-Seven Arts was theBahamas- and Switzerland-based mutual fund Investors Overseas Service(IOS), owned byBernard Cornfeld, areputed money launderer for Lansky and the mob. Allegedly in cahootswith Dino Cellini, swindler Robert Vesco took over IOS during theperiod Cornfeld was being held in prison by Swiss authoritiesinvestigating fraud (nothing was proven, and he was eventuallyreleased). Vesco defrauded IOS of $224 million in 1972, while majorDemocratic Party figures like former California governorEdmund G. Brown and PresidentFranklin D. Roosevelt'ssonJames Roosevelt served on the boardof directors. Vesco was no partisan; he made a huge illegal campaigncontribution to PresidentRichard Nixon's1972 re-election committee before going on the lam.

Nixon paid Vesco back by firingRobert Morgenthau, the U.S. Attorneyfor the southern district of New York, who was investigating Mafiamoney laundering through Switzerland. Morgenthau already had won aconviction against Max Orovitz for violating stock registration laws,and he was moving in on IOS' John King when he was unceremoniouslysacked. Although King was later convicted, he received a relativelylight sentence.

While it may seem ironic that a Democrat like Goetz would be involvedwith a possibly mobbed-up firm, one must remember that in the mid-'60s,at least 10% and as much as 20% of the Democratic Party's revenues werederived from organized crime, as in many cities, like Chicago, theDemocratic ward headquarters usually doubled as a syndicate clubhouse.The Chicago organization swung the 1960 Presidential vote in Illinoisto Kennedy. The Mafia had infiltrated Hollywood in the early 1940s, andmany of the moguls rubbed shoulders with organized crime figures at theracetracks they haunted and at which they contested their own horses.Steve Ross, the Kinney conglomerateowner that acquired Warner Bros-Seven Arts, himself was reputed to haveMafia connections (former Paramount production chiefRobert Evans boasts of hisconnections to mob lawyer and Hollywood fixer Sidney Korshak, whom hewas not above asking favors from, in his autobiography "The Kid Staysin the Picture"). Democratic SenatorEstes Kefauver had investigated the Mafiain 1951, holding televised hearings that put mob bosses such asFrank Costello on the spotand Kefauver in the spotlight. Later, Sen. John Kennedy and his brotherRobert F. Kennedy were part of thecommittee investigating the Teamsters Union for its links to the mob(interestingly, Kefauver beat Kennedy out for the vice presidentialslot on the 1956 ticket headed byAdlai Stevenson). The Democraticestablishment was more interested in investigating labor corruptionthan it was in elucidating and ending the mob's links with politiciansand legitimate businesses and businessmen, which included Kennedy's ownfatherJoseph P. Kennedy, who hadfinanced rum running by Detroit's Purple Gang during Prohibition.

This focus on labor to the detriment of the businessmen who actuallydid business with organized crime was a prejudice portrayed inHollywood films such asOn the Waterfront (1954). In"Waterfront," union officials are shown as corrupt killers, whereas thewarehouse-owner-surrogate is a sort of savior to the martyredlongshoreman played byMarlon Brando, wholeads the flock of his co-workers away from the mobbed-up union bossJohnny Friendly into the warm bosom of the owner's warehouse at the endof the movie. (ironically, playwrightArthur Miller had written ascreenplay, "The Hook," about corruption on the New York waterfront for"Waterfront" directorElia Kazan. ColumbiabossHarry Cohn, an attendee of theWaldorf Conference and a supporter of the blacklist, had demanded thatMiller change the corrupt union officials to Communists, as it wouldthen make the script "pro-American." Miller refused.).

Goetz's father-in-law, Louis B. Mayer, had been the driving forcebehind the foundation of the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts & Sciencesin 1927, which he had envisioned as a company union that wouldforestall unionization by more militant craft guilds. Mayer, throughthe Academy, managed to hold off unionization until the mid-'30s, whenthe crafts bolted the Academy and formed their own guilds. Mayer'sdream of controlling labor and keeping absolute control over laborcosts was dashed, and the Academy morphed into a scientific andresearch organization focused on publicity. By the end of the 1930s,the New York Mafia began infiltrating Hollywood through theprojectionists' union. Studio bosses such as Mayer still kept tightcontrol over labor costs, though that power began to decline in the1940s due to concessions made to rebellious stars. The DeHavillanddecision--named after a lawsuit brought against Warner Bros. by actressOlivia de Havilland--which forbadethe studios from adding on suspension time to the end of the standardseven-year contracts, also helped erode the studio's power. However, itwas Goetz's and Wasserman's profit participation contract thateffectively destroyed the studios, that and the loss of theirprofitable theater chains (Loew's Inc. managed to fend off thedivestiture for years, until well after Louis B. Mayer was forced outof MGM in favor ofDore Schary by NicholasShenck in 1951).

As the power of the vertically integrated studios waned after theirJustice Department-enforced divestiture of their movie chains, agentsrepresenting the now-free serfs who were stars moved into the breach,creating independent production companies. At the same time, the powerof organized crime, which began at roughly the same time as Hollywoodorganized itself vertically to control the chaos of movie productionand distribution, apparently waxed. A major landlord in vice districts,the Mafia controlled many old inner-city theaters abandoned by thestudios that were subsequently turned into grindhouses showcasingexploitation fare and later pornography after the breakdown ofcensorship in the 1960s and early 1970s. Corruption extended tofirst-run houses as well. Warner Communications executives in the 1970swere convicted of accepting kickbacks from movie theaters, a case inwhich Warner boss Steve Ross was considered an unindictedco-conspirator, though he vigorously denied any knowledge of wrongdoingand was never himself indicted for any crime.

Goetz was never implicated in any improprieties in all his years as amovie executive. In fact, he was something of an anomaly in Hollywood.Although he was a member of one of Hollywood's royal families, Goetzwas unusual in that he enforced a "no nepotism" policy in hiscompanies. He was renowned for his erudition and good manners in anindustry studded with vulgar (Columbia'sHarry Cohn being a stellar example)and semi-literate moguls. He eschewed a chauffeur and drove his own carto work, where he cultivated a persona as paterfamilias (as did hisfather-in-law at MGM), helping his employees with personal problems.Goetz had his personal chef oversee the preparation of food at thestudio fare.

Goetz was known for his exquisite taste, and he and his wife werecounted among the movie colony's premier art collectors, specializingin the impressionists and post-impressionists. Some of hisVincent van Gogh paintings were used inMGM'sLust for Life (1956). In 1959the Goetzs' art collection had its own show at San Francisco's artmuseum, The Palace of the Legion of Honor. Speaking about Goetz, fellowart collectorBilly Wilder said that he was"the very antithesis of being pompous . . . he had a funny cynicism." Arespected member of the community, Goetz served as a director of theCity National Bank of Beverly Hills and as a trustee of Reed College(Portland, Oregon). His last motion picture production was the mediocreKuîn Merî-gô shûgeki (1966),scripted byRod Serling.

William Goetz contracted cancer and was treated at the Mayo Clinic. OnAugust 15, 1969, he died in his Los Angeles home from complications ofthe disease. He was buried in Hillside Memorial cemetery.

All of the Goetz brothers wound up in the movie business. Two of hisbrothers worked at Monogram and were among the founders of RepublicPictures (seeHerbert J. Yates), andanother worked forCorinne GriffithProductions. In 1924 Goetz took advantage of the well-known Hollywoodpractice of nepotism and moved to Hollywood where his brothers got hima job at Corinne Griffith Productions as a crew member. Within threeyears he had worked his way up to associate producer. Goetz then movedon to production jobs at MGM and Paramount before becoming an associateproducer at Fox Films in March 1930. The first movies Goetz produced atFox were two Spanish-language westerns,El último de los Vargas (1930),based on aZane Grey novel, andFigaro e la sua gran giornata (1931),both of which starredGeorge J. Lewis as"Jorge Lewis."

A dashing man with an earthy sense of humor, Goetz marriedLouis B. Mayer's daughter Edith in 1930.Edith said her husband was a fast talker who persistently telephonedher for a date after they met at Los Angeles' Ambassador Hotel. When Goetzasked Edith to marry him Mayer objected, wanting to know how he wasgoing to support her. Goetz won Mayer's consent when he replied, "Ifnecessary, Mr. Mayer, with my own two hands." The two men wouldcontinue to argue about the proposed marriage right up until theceremony itself. Their marriage was Hollywood's wedding of the year.William and Edith's marriage lasted until his death, and they had twodaughters. His ultra-conservative father-in-law would eventuallydisinherit Edith, perhaps because of his son-in-law's key role inundermining the studio system in the 1950s, or because he was a staunchDemocrat, or possibly due to the brothers' ties to a man with reputedunderworld connections (although Mayer's ostensible bossNicholas M. Schenck, Chairman of Loew's Inc. had the same connections).

One of the most influential figures in Goetz's life would prove to beWarner Bros.' production chiefDarryl F. Zanuck, who had remarkablyrisen through the ranks of Hollywood on his own merits and who had anatural disdain for nepotism. Nearly every one of Warner Bros.'successes after 1924 could be directly credited to the workaholic (manywould add sexoholic) producer-writer-production chief. In 1933 Zanuckhad quit Warners after a long-simmering rift withHarry M. Warner. Despite being offeredseveral positions at other studios, Zanuck had a burning desire to runhis own studio and was approached by the affableJoseph M. Schenck with an offer thatwould result in the creation of Twentieth Century Pictures. The dealwas a conglomeration of backers, each with his own agenda, but eachhaving enormous confidence in Zanuck's enviable track record ofdelivering a prodigious number of hits. Twentieth Century Pictures wascreated as a partnership betweenLouis B. Mayer, former United ArtistspresidentJoseph M. Schenck and Loew's Inc. (the parent company of MGM)head Nicholas Schenck (Joe's brother and officially Mayer's boss), whoarranged for underwriting by the Bank of America with additionalbacking by the cunningly abrasiveHerbert J. Yates, who keenly sought outguaranteed business for his Consolidated Film Labs (and who would soonform Republic Pictures out of a merger among Mascot Pictures, MonogramPictures and Liberty Pictures when bankrupt producerMack Sennett's studio became available).Goetz's involvement was based on a string Mayer attached for his money:he wanted his son-in-law out from under his thumb. Whatever talentsWilliam Goetz possessed as a young man in Hollywood were lost on hisfather-in-law. Twentieth Century merged with ailing Fox Films (whichowned a desirable theater chain) in 1935, and Goetz was named vicepresident of Twentieth Century-Fox, with Zanuck over him as productionhead and Joe Schenck serving as president. In its infancy the studiorelied heavily on the talents of a small roster of popular stars suchasTyrone Power,Don Ameche andAlice Faye, but found a gold mine in anadorable and monumentally talented six-year-old moppet namedShirley Temple, who literally kept thethe ink from turning red. Among the 20th Century-Fox pictures Goetzpersonally produced wereRothschild (1934),for which he received an Academy Award nomination for Best Picturealong with Zanuck;Les Misérables (1935), a classicHollywood production ofVictor Hugo's novel; and a hitadaptation ofJack London'sThe Call of the Wild (1935),which starred MGM loan-outClark Gable,Loretta Young (who got pregnant by Gableduring production) andJack Oakie.Goetz's stock at the studio began to rise and he gained a reputationfor being an efficient, unassuming producer who (most importantly)could bring a project in at or under budget. At the outbreak of WWII,Zanuck eagerly accepted an army commission and placed Goetz as actinghead of the studio in 1942. As production head, Goetz was responsiblefor some prestigious films that brought credit to both him and thestudio, includingGuadalcanal Diary (1943) andtheThe Song of Bernadette (1943),which was nominated for 12 Academy Awards and won four, including aBest Actress Oscar forJennifer Jones, who wouldeventually become the wife of Goetz's then brother-in-law,David O. Selznick.

Like his father-in-law Louis B. Mayer, Goetz emphasized quality todistinguish his product in the market, and he did not flinch fromspending money to achieve it. Unlike Mayer, however, Goetz learned themechanics of bringing a project through to completion. Hollywood is atown where paranoid bosses push many ambitious men out of theirpositions, though, and 20th Century-Fox was no different. Zanuck stillregarded Goetz as an unimaginative administrator and began hearingrumors that Goetz was growing ambitious. Goetz, however, resigned uponZanuck's return in 1943 to avoid any conflict. Zanuck was also said tobe furious that Goetz had turned his special 4:00 p.m. casting couchinterview room into a storage area.

Mayer, belatedly recognizing Goetz's production talents, offered him achance to be the head of MGM's creative development, but Goetz told hiswife that he had to turn her father down, since the first thing hewould have done at MGM was fire Mayer. Zanuck's 1942-43 absence hadgiven Goetz a taste of running a studio, and since there were no jobson offer to become a studio boss, he created International Pictures in1943 with lawyer Leo Spitz, who had been an adviser to Goetz'sbrother-in-law David O. Selznick. One of the great independentproducers, Selznick had produced the most successful movie of all time,Kaze to tomo ni sarinu (1939),which he found impossible to bring to the screen without help fromMayer, given MGM's irreplaceable Rhett Butler: Gable. Like Zanuck adozen years earlier, Goetz opted to strike out on his own withInternational Pictures (Selznick was furious about that name, believingit conflicted with his own Selznick International Pictures).

During its brief life as an independent company, International Picturesproduced ten middling films distributed by United Artists beforemerging with Universal Pictures to create Universal-InternationalPictures in 1945, with Goetz being appointed production chief. As U-Istudio boss, Goetz partnered with British producerJ. Arthur Rank to release Rank'sBritish-produced films in America. A major stockholder, Rank at onepoint tried to take over the studio, but he proved unsuccessful. UnderGoetz's direction, U-I became known for family fare and well-craftedB-pictures, including the long-runningBud Abbott andLou Costello series of comedies, the"Francis the Talking Mule" series and the popular "Ma and Pa Kettle"movies. These would eventually become repetitious and Goetz had noparticular fondness for inane comedies, but they were money in the bankfor U-I.

Goetz participated in the 1946 Waldorf Conference with hisfather-in-law, MGM capo di tutti capi Nicholas Schenck, and other topstudio executives. The conference was a studio boss pow-wow called byMotion Pictures Producers Association President Eric Johnston, who wasin a panic over the so-called "Hollywood Ten", a group of Hollywoodcreative people who were indicted after failing to testify before theHouse Un-American Activities Committee looking for evidence ofCommunist "subversion" in the motion picture industry. It was at theWaldorf Conference that the Hollywood blacklist was devised, with theaim of ridding the industry of any Communistsm real, suspected orimagined. What it did do was rein in the effect of New Dealprogressives who may have proved too radical for the movie moguls'tastes when it came to labor relations.

Some commentators believe the real deal struck at the WaldorfConference was an agreement to break the militants in the craft unionsby tarring them as "Reds". An ancillary part of this deal, as theargument goes, was an agreement to place in control of the unions menwho had strong ties to organized crime, in order for them to offer thebosses sweetheart deals and put an end to the labor unrest thatHollywood experienced as World War II came to a close. The studios hadalready suffered through a 13-week strike the year before.

The strike was launched on March 12, 1945, when the Conference ofStudio Unions (CSU) went out in protest of the studios' delay inrenewing the contract for interior decorators. The strike had beenopposed by IATSE, which had been under the control of the Chicago mobin the 1930s and early 1940s. The studios had surreptitiously called onMafia muscle to attempt to break up the strike. CSU officials werebranded "Reds" and "Communist subversives" and harassed.Ronald Reagan, the future ScreenActors Guild (SAG) president, had volunteered to be an informer againstthe CSU, snitching to the FBI on its activities.

Goetz signed on to the blacklist, perhaps realizing he could notalienate his fellow studio bosses if he was to establishUniversal-International Pictures on a sound footing, as he needed tocurry their favor to get loan-outs of their stars. U-I's major problemwas that it had no box-office stars.Rock Hudson,Tony Curtis andJeff Chandler were contractplayers, but their careers had not yet bloomed. U-I thus had to rely onthe good will of the other studio bosses until it could establishitself as a major player.

In 1949 Goetz and his good friend, super-agentLew Wasserman, engineered the first profitparticipation deal in motion picture history. U-I wanted Wasserman'sclient,James Stewart, recentlyout of his contract at MGM, to appear inAnthony Mann's new Western,Winchester '73 (1950). Goetz felthe was unable to obtain funds necessary for such a costly production upfront, so he signed Stewart to a deal that gave him half of the profitsof the picture rather than a set fee.

Wasserman had wanted to establish Stewart, an independent contractor,as a corporation to protect him from the then-prohibitive income tax,which topped out at 90% for earners of Stewart's caliber. By making hima producer, Wasserman put Stewart in a lower tax-rate via a productioncompany that would take a tax-favored stake in his movies in lieu of apersonal fee. Stewart's production company would then be taxed at thelower corporate rate.

Stewart netted $750,000 from the deal, with U-I netting the same amount(while the deal cost the studio a greater percentage of profits from ahit, it was also insulated from the losses that possibly could begenerated by a failure, as it lowered production costs). Regardless, itwas a fortuitous deal since the picture was, deservedly, a smash hit. Aprofit participation deal was again used on U-I's excellentStewart-Mann westernBend of the River (1952).

The profit participation deal was revolutionary--- it would ultimatelyunravel the entire studio system, and would soon be copied by otherindependent-minded stars. Many of them would refuse to sign newcontracts with their studios in order to go independent and takeadvantage of percentage deals. It proved to be the straw that finallybroke the studio system's back (having lost proprietary theaterownership in the 1950s was another crippling blow, along with thecompetition from a new medium, television). With profit participationdeals, power shifted from the studios to the stars and their agents.Studios now became financiers and renters of production facilities.

Although U-I shared in the profits of its profit-participationcontracts with Stewart, who became a top-10 box office star for thefirst time in the 1950s appearing in U-I westerns, it did not reverse afinancial slump the studio underwent in the early 1950s. U-I wasfinancially weak and succumbed to a 1952 take-over by Decca Records.

Wasserman's MCA, an entertainment conglomerate that began as a talentagency but thrived as a leading TV producer due to a secret waivergranted it by SAG when it was headed by Wasserman client Ronald Reagan,ultimately would buy U-I by acquiring Decca Records in 1962 (Wassermanand MCA chairmanJules Stein reportedly hadclose ties to the Chicago mob; as late as 1984, a Mafia enforcerbelonging toJohn Gotti's Gambino crimefamily with "a past history of arranging narcotics smuggling,"according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency, was serving as amiddleman for MCA despite having no prior experience in the musicindustry. An investigation into MCA in the mid-'80s was quashed bythen-President Ronald Reagan's Justice Department. Wasserman hadremained close to Reagan, a man he had made a millionaire by giving himan ownership stake in the TV seriesDeath Valley Days (1952)and also through a land deal. Through Wasserman, Reagan had becomewealthy enough to pursue a political career after his acting careerended in 1964. Despite being a liberal Democrat, Wasserman raised moneyfor Reagan's first gubernatorial campaign as a right-wing Republicanand served as the chief fundraiser for his presidential library.

Goetz left the studio in 1954 and went independent, having obtained adistribution deal through Columbia for his William Goetz Productions.Films produced by the independent Goetz were nominated three times forGolden Globes:Sayonara (1957), whichgarnered Academy Award nominations for Goetz, directorJoshua Logan, starMarlon Brando and Best Supporting Oscarsfor featured playersRed Buttons andMiyoshi Umeki;Me and the Colonel (1958), aHolocaust comedy starringDanny Kaye; andSong Without End (1960), amusical about composerFranz Lisztco-directed byGeorge Cukor, which wonGoetz the Best Musical Song from the Hollywood Foreign PressAssociation, and an Oscar for Best Music.

Like many movie moguls, including Nicholas Schenck and hisfather-in-law, Goetz raised thoroughbreds. He bought his first racingstock from L.B, a famous horse breeder who got out of the racingbusiness after World War II, as it was bad for his image. Goetz's horseYour Host won the 1950 Santa Anita Derby and subsequently sired Kelso,one of the all-time money winners.

Goetz terminated his production company in 1961 after making theGlenn Ford service comedyCry for Happy (1961), but he cameout of retirement in 1964 to take the job of vice president at SevenArts Productions Ltd., a Canadian-controlled production anddistribution corporation. Goetz possibly took the job as a favor to hisfriend Lew Wasserman, as the major stockholder in Seven Arts, LouisChesler, had ties to the Chicago mob, as did Wasserman in his earlydays as a musician and recording artists' agent. Significantly, Cheslerhad served on the board of directors of Allied Artists, a subsidiary ofhis brothers' defunct Monogram Pictures.

Chesler, an aficionado of horse-racing like Goetz and a reputedgambler, was the driving force behind Seven Arts Productions, which wascapitalized on Toronto's stock exchange. In addition to investing inthe entertainment field, the 300-pound entrepreneur was a major housingdeveloper in Florida. Chesler was described as a front or associate ofunderworld crime bossesVito Genovese andMeyer Lansky through the Florida realestate company General Development Corp., which he owned with anotherLasky associate, Wallace Groves.

General Development's board of directors included gangster "TriggerMike" Coppola and Max Orovitz, who was Lansky's stockbroker. Anotherpartner wasEddie DeBartolo, a shoppingmall developer and racetrack owner with a taste for high-stakesgambling. DeBartolo, who bought the San Francisco 49ers professionalfootball team for his son,Edward DeBartolo Jr., was close toLansky and Lansky associatesCarlos Marcello, who controlledFlorida's narcotics and gambling, and New Orleans Mafia bossSanto Trafficante Jr.. Both Marcello andTrafficante, who owed fealty to the Chicago mob, had been recruited viaChicago bossSam Giancana to assassinateCuban leaderFidel Castro for theCIA, which they were glad to do, as Castro had booted them and Lanskyout of Cuba--where they controlled lucrative gambling, narcotics,prostitution and other criminal activities--after the 1959 revolution(some conspiracy theorists place the responsibility for PresidentJohn F. Kennedy's assassination onMarcello and Trafficante, though that has never been proven.)

Through General Development Corp., Chesler and Groves introducedgambling to the Bahamas, buying half of Grand Bahama Island and settingup the Grand Bahama Development Co. in the early 1960s to build a hotelcum casino. It was through Chesler that the Bahamian gaming businesswas penetrated by Lansky, looking for a new territory after losingCuba, and Dino Cellini, a mob banker described as Lansky's right-handman, the person he most trusted with the receipts from his gamblingoperations. One of Chesler's partners in the Bahamas was CarrollRosenbloom, owner of the Los Angeles Rams and one of the three largestshareholders in Seven Arts, who was described as a notorious gambler.

Although Chesler is credited with opening up the British crown colonyto gambling, having done most of the schmoozing and covert briberythrough the awarding of "consulting fees" to well-connected politiciansand colonial bureaucrats, he was forced out of the Bahamas in a powerstruggle in 1964. Chesler's story, well known in the 1960s, likely wasone of the inspirations for Michael Corleone's Cuban sojourn andbusiness dealings with Hyman Roth--a character based on MeyerLansky--inGodfather Part II (1974).

Lansky's gang ran the "skim" of Bahamian casino money that wasrepatriated to mob banks in Miami controlled by Cellini, who had towork in London and Rome, as he was persona non grata in Florida and theBahamas. Subsequently, development in the Bahamas hit a downturn andthe Canadian holding company Atlantic Acceptance, a major source ofcapital, went bankrupt in June 1965. The company's $104-million defaulttouched off an international financial scandal. Although Cheslerliquidated the rest of his holdings by the end of 1966, he had put hisstamp on the Bahamas by creating the island's gaming industry andintroducing the Lansky gang to the islands.

In 1967 his company, now called Seven Arts Ltd., acquiredJack L. Warner's controlling interest inWarner Bros. Pictures and other interests, including Warner Bros.Records and Reprise Records (the $84-million price tag of theacquisitions was worth approximately $640 million in 2003 dollars). Thecompany was renamed Warner Bros-Seven Arts. The ambitious studio boughtAtlantic Records for $17 million in stock that same year but, crippledby debt, the company itself was acquired by the conglomerate KinneyNational Services Inc. in 1969, the year of Goetz's death.

One of the major shareholders in Warner Bros-Seven Arts was theBahamas- and Switzerland-based mutual fund Investors Overseas Service(IOS), owned byBernard Cornfeld, areputed money launderer for Lansky and the mob. Allegedly in cahootswith Dino Cellini, swindler Robert Vesco took over IOS during theperiod Cornfeld was being held in prison by Swiss authoritiesinvestigating fraud (nothing was proven, and he was eventuallyreleased). Vesco defrauded IOS of $224 million in 1972, while majorDemocratic Party figures like former California governorEdmund G. Brown and PresidentFranklin D. Roosevelt'ssonJames Roosevelt served on the boardof directors. Vesco was no partisan; he made a huge illegal campaigncontribution to PresidentRichard Nixon's1972 re-election committee before going on the lam.

Nixon paid Vesco back by firingRobert Morgenthau, the U.S. Attorneyfor the southern district of New York, who was investigating Mafiamoney laundering through Switzerland. Morgenthau already had won aconviction against Max Orovitz for violating stock registration laws,and he was moving in on IOS' John King when he was unceremoniouslysacked. Although King was later convicted, he received a relativelylight sentence.

While it may seem ironic that a Democrat like Goetz would be involvedwith a possibly mobbed-up firm, one must remember that in the mid-'60s,at least 10% and as much as 20% of the Democratic Party's revenues werederived from organized crime, as in many cities, like Chicago, theDemocratic ward headquarters usually doubled as a syndicate clubhouse.The Chicago organization swung the 1960 Presidential vote in Illinoisto Kennedy. The Mafia had infiltrated Hollywood in the early 1940s, andmany of the moguls rubbed shoulders with organized crime figures at theracetracks they haunted and at which they contested their own horses.Steve Ross, the Kinney conglomerateowner that acquired Warner Bros-Seven Arts, himself was reputed to haveMafia connections (former Paramount production chiefRobert Evans boasts of hisconnections to mob lawyer and Hollywood fixer Sidney Korshak, whom hewas not above asking favors from, in his autobiography "The Kid Staysin the Picture"). Democratic SenatorEstes Kefauver had investigated the Mafiain 1951, holding televised hearings that put mob bosses such asFrank Costello on the spotand Kefauver in the spotlight. Later, Sen. John Kennedy and his brotherRobert F. Kennedy were part of thecommittee investigating the Teamsters Union for its links to the mob(interestingly, Kefauver beat Kennedy out for the vice presidentialslot on the 1956 ticket headed byAdlai Stevenson). The Democraticestablishment was more interested in investigating labor corruptionthan it was in elucidating and ending the mob's links with politiciansand legitimate businesses and businessmen, which included Kennedy's ownfatherJoseph P. Kennedy, who hadfinanced rum running by Detroit's Purple Gang during Prohibition.

This focus on labor to the detriment of the businessmen who actuallydid business with organized crime was a prejudice portrayed inHollywood films such asOn the Waterfront (1954). In"Waterfront," union officials are shown as corrupt killers, whereas thewarehouse-owner-surrogate is a sort of savior to the martyredlongshoreman played byMarlon Brando, wholeads the flock of his co-workers away from the mobbed-up union bossJohnny Friendly into the warm bosom of the owner's warehouse at the endof the movie. (ironically, playwrightArthur Miller had written ascreenplay, "The Hook," about corruption on the New York waterfront for"Waterfront" directorElia Kazan. ColumbiabossHarry Cohn, an attendee of theWaldorf Conference and a supporter of the blacklist, had demanded thatMiller change the corrupt union officials to Communists, as it wouldthen make the script "pro-American." Miller refused.).

Goetz's father-in-law, Louis B. Mayer, had been the driving forcebehind the foundation of the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts & Sciencesin 1927, which he had envisioned as a company union that wouldforestall unionization by more militant craft guilds. Mayer, throughthe Academy, managed to hold off unionization until the mid-'30s, whenthe crafts bolted the Academy and formed their own guilds. Mayer'sdream of controlling labor and keeping absolute control over laborcosts was dashed, and the Academy morphed into a scientific andresearch organization focused on publicity. By the end of the 1930s,the New York Mafia began infiltrating Hollywood through theprojectionists' union. Studio bosses such as Mayer still kept tightcontrol over labor costs, though that power began to decline in the1940s due to concessions made to rebellious stars. The DeHavillanddecision--named after a lawsuit brought against Warner Bros. by actressOlivia de Havilland--which forbadethe studios from adding on suspension time to the end of the standardseven-year contracts, also helped erode the studio's power. However, itwas Goetz's and Wasserman's profit participation contract thateffectively destroyed the studios, that and the loss of theirprofitable theater chains (Loew's Inc. managed to fend off thedivestiture for years, until well after Louis B. Mayer was forced outof MGM in favor ofDore Schary by NicholasShenck in 1951).

As the power of the vertically integrated studios waned after theirJustice Department-enforced divestiture of their movie chains, agentsrepresenting the now-free serfs who were stars moved into the breach,creating independent production companies. At the same time, the powerof organized crime, which began at roughly the same time as Hollywoodorganized itself vertically to control the chaos of movie productionand distribution, apparently waxed. A major landlord in vice districts,the Mafia controlled many old inner-city theaters abandoned by thestudios that were subsequently turned into grindhouses showcasingexploitation fare and later pornography after the breakdown ofcensorship in the 1960s and early 1970s. Corruption extended tofirst-run houses as well. Warner Communications executives in the 1970swere convicted of accepting kickbacks from movie theaters, a case inwhich Warner boss Steve Ross was considered an unindictedco-conspirator, though he vigorously denied any knowledge of wrongdoingand was never himself indicted for any crime.

Goetz was never implicated in any improprieties in all his years as amovie executive. In fact, he was something of an anomaly in Hollywood.Although he was a member of one of Hollywood's royal families, Goetzwas unusual in that he enforced a "no nepotism" policy in hiscompanies. He was renowned for his erudition and good manners in anindustry studded with vulgar (Columbia'sHarry Cohn being a stellar example)and semi-literate moguls. He eschewed a chauffeur and drove his own carto work, where he cultivated a persona as paterfamilias (as did hisfather-in-law at MGM), helping his employees with personal problems.Goetz had his personal chef oversee the preparation of food at thestudio fare.

Goetz was known for his exquisite taste, and he and his wife werecounted among the movie colony's premier art collectors, specializingin the impressionists and post-impressionists. Some of hisVincent van Gogh paintings were used inMGM'sLust for Life (1956). In 1959the Goetzs' art collection had its own show at San Francisco's artmuseum, The Palace of the Legion of Honor. Speaking about Goetz, fellowart collectorBilly Wilder said that he was"the very antithesis of being pompous . . . he had a funny cynicism." Arespected member of the community, Goetz served as a director of theCity National Bank of Beverly Hills and as a trustee of Reed College(Portland, Oregon). His last motion picture production was the mediocreKuîn Merî-gô shûgeki (1966),scripted byRod Serling.

William Goetz contracted cancer and was treated at the Mayo Clinic. OnAugust 15, 1969, he died in his Los Angeles home from complications ofthe disease. He was buried in Hillside Memorial cemetery.

BornMarch 24, 1903

DiedAugust 15, 1969(66)

- Nominated for 1 Oscar

- 1 win & 1 nomination total

Producer

Production Management

Actor

- Alternative name

- Mr. William Goetz

- Born

- Died

- Spouse

- Edith MayerMarch 19, 1930 - August 15, 1969 (his death, 2 children)

- Publicity listings

- TriviaSon-in-law ofLouis B. Mayer.

- Nicknames

- Billy

- Bill

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content