King David playing on hand-bells.

From a manuscript Psalter in the British Museum. Thissubject was often selected for the heading to the forty-sixthPsalm, as here. (See page6).

TheArts of the Church

Edited by the

REV. PERCY DEARMER, M.A.

The Arts of the Church

Edited by the

REV. PERCY DEARMER, M.A.

16mo. Profusely Illustrated. Cloth, 1/6 net.

1.THE ORNAMENTS OF THEMINISTERS. By the Rev.PercyDearmer, M.A.

2.CHURCH BELLS. ByH. B.Walters, M.A., F.S.A.

3.THE ARCHITECTURAL HISTORYOF THE CHRISTIANCHURCH. ByA. G. Hill, M.A.,F.S.A.

OTHERS TO FOLLOW

King David playing on hand-bells.

From a manuscript Psalter in the British Museum. Thissubject was often selected for the heading to the forty-sixthPsalm, as here. (See page6).

The Arts of the Church

BY

H. B. WALTERS, M.A., F.S.A.

Author ofGreek Art, &c.

WITH THIRTY-NINE ILLUSTRATIONS

A. R. MOWBRAY & CO.Ltd.

London: 34 Great Castle Street, Oxford Circus, W.

Oxford: 9 High Street

First printed, 1908

The little volumes in theArts ofthe Church series are intendedto provide information in an interestingas well as an accurate form about thevarious arts which have clustered roundthe public worship ofGod in the ChurchofChrist. Though few have the opportunityof knowing much about them,there are many who would like to possessthe main outlines about those arts whoseproductions are so familiar to the Christian,and so dear. The authors will writefor the average intelligent man who hasnot had the time to study all these mattersfor himself; and they will therefore avoidtechnicalities, while endeavouring at thesame time to present the facts with afidelity which will not, it is hoped, beunacceptable to the specialist.

Acknowledgements must beexpressed to the following personswho have assisted in supplying photographsor other materials for the illustrationsto this book: to the Rev. W. H.Frere, Mr. A. Riley, and the Committeeof the Alcuin Club for permission toreproduce in plate4 a page of a MS.Pontifical; to Dr. Amherst D. Tyssenand the Rev. Dr. Jessopp for blocks; toW. Watson, Esq., of York, and MissWilson of Idbury for photographs; toMessrs. Wills and Hepworth of Loughborough,Messrs. Mears and Stainbank,and Messrs. Taylor and Co. of Loughboroughfor blocks, negatives and photographs.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Early History and Methods of Casting | 1 |

| II. | The English Bell-founders | 21 |

| III. | Big Bells; Carillons and Chimes; Campaniles | 43 |

| IV. | Change-Ringing | 67 |

| V. | Uses and Customs of Bells | 81 |

| VI. | The Decoration of Bells and their Inscriptions | 105 |

| VII. | The Care of Bells | 139 |

| Index | 157 | |

| PAGE | |

| King David playing on hand-bells | Frontispiece |

| Saxon Tower, Earl’s Barton | 3 |

| A performer on hand-bells | 7 |

| Tower or Turret with Bells | 11 |

| Blessing two bells newly hung | 15 |

| Late Norman bell-turret at Wyre | 19 |

| Inner moulds for casting bells | 23 |

| Outer moulds for casting bells | 27 |

| Moulds ready for casting | 31 |

| Forming the mould | 35 |

| Running the molten metal | 39 |

| The Mortar of Friar Towthorpe | 42 |

| Bell by an early fourteenth-century founder | 47 |

| Blessing the Donor of the bell | 51 |

| Stamps used by London Founders | 54 |

| Bell by Robert Mot of London | 59 |

| A ring of eight bells | 63 |

| The 9th bell of Loughborough Church | 66 |

| Tenor bell of Exeter Cathedral | 73 |

| [Pg xii]“Great John of Beverley” | 77 |

| The great bell of Tong | 83 |

| “Great Paul” | 87 |

| The old “Great Tom” of Westminster | 91 |

| The Belfry of Bruges | 94 |

| The Campanile, Chichester Cathedral | 99 |

| The old Campanile of King’s College, Cambridge | 102 |

| The “Bell House” at East Bergholt | 107 |

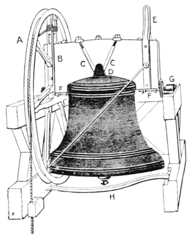

| Diagram showing method of hanging a bell | 110 |

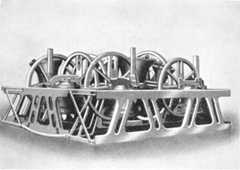

| Peal of eight bells, Aberavon Church | 113 |

| Ringers at S. Paul’s Cathedral | 119 |

| Ringing the Sacring bell | 123 |

| Sacring bell hung on rood-screen | 126 |

| Ancient Sanctus Bell | 129 |

| Tower of Waltham Abbey Church | 133 |

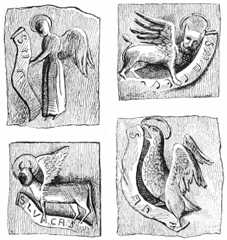

| Symbols of the Four Evangelists | 137 |

| Bell by John Tonne | 141 |

| Gothic Initial Letters, etc. | 145 |

| Gol„lic Ini„ial Let„ | 149 |

| Part of a seventeenth-century bell | 153 |

CHURCH BELLS

The origin of the bell as an instrumentof music is, one may almost say, lostin antiquity. Its use is, moreover, widelyspread over the whole world. But I donot propose to enlarge on its early historyhere, or on its employment by all nations,Christian or heathen. Space will not permitme to do more than trace its historyand uses in the Christian Church, and moreparticularly in the Church of England.

The word “bell” is said to be connectedwith “bellow” and “bleat” and to refer to[Pg 2]its sound; the later Latin writers call it,among other names,campana, a word withwhich we are familiar, not only as frequentlyoccurring in old bell inscriptions,but as forming part of the word “Campanalogy,”or the science of bell-ringing.The French and Germans, again, call itcloche andglocke respectively, the wordsbeing the same as our “clock”; but thatis a later use, and they really mean “cloak,”with reference to the shape of the bell, orrather of the mould in which it is cast.Modern bell-founders, it is interesting tonote, speak of the mould as thecope, whichagain suggests a connection with the formof a garment.

It is not known exactly when bells wereintroduced into the Christian Church; butit is certain that large bells of the formwith which we are familiar were not inventeduntil after some centuries ofChristianity. The small and often clandestinecongregations of the ages ofpersecution needed no audible signal to[Pg 4]call them together; but with the adventof peaceful times, and the growth of thecongregations, some method of summonsdoubtless came to be considerednecessary. Their invention is sometimesascribed to Paulinus, Bishop of Nola, inItaly, aboutA.D. 400; sometimes to PopeSabinianus (A.D. 604), the successor ofGregory the Great. At all events, fromthe beginning of the seventh centurynotices of bells of some size becomefrequent. The Venerable Bede in 680brought a bell from Italy to place in hisAbbey at Wearmouth, and mentions one asbeing then used at Whitby Abbey. About750, we read that Egbert, Archbishop ofYork, ordered the priests to toll bells at theappointed hours. Ingulphus, the chroniclerof Croyland Abbey, mentions that a pealof seven bells was put up there in thetenth century, and that there was not sucha harmonious peal in the whole of England;which implies that rings of bellswere then common. If any doubt on the[Pg 5]matter still remained, it would be dispelledby the existence to this day of some hundredchurch towers dating from the Saxonperiod, and evidently, by their size andconstruction, intended to hold rings ofbells (Plate1).

| Photo by] | [C. Law. |

Saxon Tower, Earl’s Barton, Northants.

A tower built in the first half of the eleventh century andintended to contain bells. (See page5.)

I speak of “rings of bells”—and thatis a more correct term than “peal,” whichrefers to the sound they make—but itmust be remembered that in those daysbells were not rung as in modern times.At best they were “chimed,” i.e., soundedwithout being rung up; but change-ringing,which implies the full swinging roundof the bell through a complete circle, so thatthe clapper strikes twice in each revolution,was only introduced in the seventeenthcentury, and moreover has always beenpeculiar to this country.

Several ancient manuscripts have pictureswhich throw light on the use of bellsin early times, as, for instance, one whichdepicts a performer on a row of small“hand-bells” suspended from an arch,[Pg 6]which he strikes with a hammer (Plate2). Another portrays King David engagedin a similar act (Frontispiece); andothers give representations of church towersor turrets with bells hanging in them,apparently without wheels or ringing arrangements(Plate3). In the Bayeuxtapestry there is a representation of thefuneral of Edward the Confessor, in whichthe corpse is accompanied by two boys,each ringing a pair of hand-bells.

From a manuscript in the British Museum.

Two bells hung in a church tower or turret; the methodof hanging not shown. (See page6.)

Ancient bells were invariably dedicatedwith elaborate ceremonies, and were baptizedwith the name of the saint or otherperson after whom they were named (Plate4). The bells at Croyland, just mentioned,were named Pega, Bega, Turketyl,Tatwin, Bartholomew, Betelin, and Guthlac.There is, however, much disputing as tothe exact ceremonies employed, someauthorities maintaining that bells wereneither baptized nor even “washed,” butmerely blessed and consecrated, so as tobe set apart from all secular uses.

In the Norman and early Plantagenetperiod the use of bells must have beengenerally recognized. In London we hearof one Alwoldus, acampanarius (1150),which can only mean “bell-founder.” Andas early as the reign of Richard I the Guildof Saddlers were granted the privilege ofringing the bells of the Priory of S. Martin-le-Grandon the occasion of their bi-weeklymasses in the church. The priory was alsoentitled to claim the sum of 8d. for ringingat the funeral of deceased members ofthe Guild. Some of the bell-cotes of oursmaller parish churches, as at Northboroughin Northants and Manton, Rutland, appearto date from the Norman period (Plate5).In the twelfth century Prior Conradgave five large bells to Canterbury Cathedral,and in 1050 there were seven atExeter; to ring the former no less thansixty-three men were required!

But these are all mere historical records,and it may be of more interest to knowwhether any bells of this remote date still[Pg 9]exist in England. With one or two exceptions,bells did not begin to bear inscriptionsuntil the fourteenth century, andeven then we do not find dates upon them.The only early-dated bells in England areat Claughton, in Lancashire (1296), andCold Ashby, Northants (1317). Thereare, however, here and there bells of apeculiar shape which it is possible to assignto a period previous to the fourteenth century.They are long and cylindrical inform, with hemispherical or square heads,and usually very unpleasing in tone, as thestraight sides check vibration. One suchbell, formerly in Worcester Cathedral, andnow in the possession of Lord Amherst ofHackney, must belong to the ring put upby Bishop Blois in 1220 in honour of ourLord and His Mother. Even more remarkableis a bell at Caversfield in Oxfordshire,dedicated “in honour of S. Lawrence,”a long inscription on the edgeshowing that it was given by Hugh Gargate,Lord of the Manor in the reign of[Pg 10]King John (about 1210), and Sybilla hiswife. Such an inscription is very rare atthis early date; and it is interesting tonote that it is in plain Roman or Saxoncapital letters, whereas all the later inscribedbells have what are known asGothic or Lombardic letters, which camein about the end of the thirteenth century.Most counties possess examples of theselong, narrow bells; they are speciallycommon in Shropshire and Northumberland.

The earliest bells were probably notcast, but made of metal plates rivetedtogether, like the modern cow-bell. Nota few bells of this kind have been unearthedat different times, but they are allmere hand-bells of very remote date, i.e.,before the Norman Conquest, and theprocess of casting must have been introducedin very early times into England.

Bell-metal is a compound of copper andtin, in varying proportions, but usually[Pg 12]three to four parts of copper to one partof tin. The former metal adds strengthand tenacity to the bell, the latter bringsout its tone. The popular superstitionthat silver improves the tone of bells isnot only entirely baseless, but in point offact it has just the opposite effect! Thenumerous stories which are current, ofsilver being thrown into bells at theircasting, of which Great Tom of Lincolnis an example, must therefore be discredited.In recent years steel bells havebeen made by one English firm, but theyare only one degree less objectionable thanthe tubes of metal which are sometimesalso dignified by the name.

The process of casting a bell, as employedboth by ancient and modern founders, maybe described somewhat as follows:—Thefirst business is the construction of thecore, a hollow cone of brick somewhatsmaller than the inner diameter of theintended bell, over which is plastered aspecially-prepared mixture of clay, bringing[Pg 13]it up to the exact size and shape of theinterior of the bell. This was usuallymodelled with the aid of a wooden “crook,”something like a pair of compasses; butis now done with an iron framework calleda “sweep,” which revolves on a pivot andmoulds the core by means of metal blades.This clay mould is then baked hard bymeans of a fire lighted within it. Thenext stage was the construction of thecope or outer casing of the mould, whichused to be also made in hard clay, its innersurface following theouter shape anddimensions of the bell. The “thickness”of the bell itself, i.e., the part to be occupiedby the molten metal, was formedin a friable composition which was laidover the core and then destroyed. Inmodern times the “thickness” has beendispensed with, the cope being formed bylining a casing of cast iron with clay shapedto the external form and dimensions of thebell. The mould is now complete, exceptfor providing for the cannons or metal[Pg 14]loops which attach the bell to the stock,and the loop to which the clapper is suspendedinside. Every care having beentaken to adjust the respective positions ofthe cope and core with exactness, themolten metal is then poured in throughan opening, and left to cool, after whichthe bell comes out complete. The processis analogous to that known ascire perdu,employed by sculptors for the casting ofbronze statues. Illustrations of the mouldingprocesses are given in Plates6–10.

Inscriptions and ornaments are producedin relief on the bell from stamps, alsoin relief, which are pressed into the mould,making a hollow impression in it. Copiesof coins were often produced in this wayby the older founders. Down to aboutthe end of the seventeenth century eachletter, or sometimes each word, was placedon a separatepatera or tablet of metal.The usual place for the inscription is justbelow the “shoulder”-angle; but modernfounders prefer the middle or “waist.”

The blessing of two bells newly hung in achurch tower.

From a MS. Pontifical of the fifteenth century. (See page6.)

A very interesting illustration of theseprocesses is given in the famous bell-founder’swindow in the north aisle ofYork Minster, dating from the fourteenthcentury, part of which is here reproduced.The window is divided into three lights,each having five compartments, and ineach light is a large principal subject surroundedby ornamentation in the form ofbells, grotesque animals, and other devices,with two rows of bells hanging in trefoil-headedarches above. In the central compartmentof the middle light (Plate13)the subject is the blessing by an archbishopof the bell-founder, who kneels in a supplicatingattitude; in his hands is a scrollinscribed with his name,RICHARD TUNNOC,and under the canopy above the groupa bell is suspended.

The other two lights have as their mainsubjects scenes from the actual processesof bell-founding. In the left-hand light(Plate9) we have the forming of theinner mould or “core,” as already de[Pg 17]scribed.One figure is turning it witha handle like that of a grindstone, whileanother moulds the clay to its proper formwith a long crooked tool. The core restson two trestles, between the legs of whichtwo completed bells are seen; above area bell and a scroll with the founder’s name.In the right-hand window (Plate10) arethree figures engaged in running themolten metal, which is coloured red. Themetal is kept heated in the furnace bymeans of bellows, worked by two boys,while the chief workman watches themolten stream running into the mould.

The next process, in the case of a“ring” of bells, is the tuning which isgenerally necessary, though sometimes thefounder is fortunate enough to turn outwhat is known as a “maiden peal.” Formerlythis was done by chipping the insideof the bell or cutting away the edge of thelip. But it is now more effectively accomplishedby a vertical lathe, driven by steam.The modern bell-founder can attain to[Pg 18]much greater exactness in this respect,because it is now recognized that there isa regular ratio between the weight of a belland its diameter, and that a certain size orweight implies a certain musical note.Thus for a ring of eight in the key of F,the weight of the tenor would be 14 cwt.,and its diameter at the mouth reckonedat 42 inches, the treble 5 cwt., and itsdiameter 29 inches.

The frames are made separately, andthe bells hung on them in the tower withtheir headstocks already attached[1]; untilrecently all these fittings were made ofwood, and iron or brass were only usedfor the smaller parts, but it is now thecustom of some founders to employ ironframes, and even iron stocks, which maybe an improvement in lightness and stability,or for ringing purposes, but arehardly so in appearance.

| Photo by] | [J. Glover, Pershore. |

Late Norman bell-turret (about 1180) atWyre Church, Worcestershire.

There are openings for two bells, but only one is nowused. (See page8.)

In early mediaeval times it is probablethat bell-founding was largely the workof the monastic orders. It was regardedrather as a fine art than a trade, and ecclesiasticsseem to have vied in producingthe most ingenious and recondite Latinrhyming verses to adorn their bells.S. Dunstan, whose skill as a smith isfamiliar to all, is known to have beeninstrumental in hanging, if not in castingbells; and at Canterbury he gave carefuldirections for their correct use. S. Ethelwold,Bishop of Winchester 963–984, castbells for Abingdon Abbey. In the museumat York there is a mortar of bell-metal castby Friar William de Towthorpe, with the[Pg 22]date 1308 (Plate11); but this belongs tolater times, when a class of professionalfounders had sprung up, and is thereforeexceptional. We read, however, of SirWilliam Corvehill, a monk of WenlockPriory, who died shortly after its dissolution,in 1546, that he “could make organs,clocks, and chimes,” and was “a good bell-founderand maker of the frames for bells.”It has not been possible to trace his workin any existing bells.

From time to time, however, we hearof professional bell-founders, as they maybe termed, and even in the thirteenth centuryfoundries appear to have been startedin London, Bristol, Gloucester, and York.The London “belleyeteres,” as they arecalled, early attained a position of importance.Many of them are mentioned incontemporary records of the fourteenthcentury; of others we have the existingwills, which enable us to trace the successionfrom one generation to another; andagain the names of several occur on bells[Pg 24]of this period, contrary to the usual mediaevalpractice. In the days when work forthe Church was a labour of love, lessimportance was attached to self-advertisement;though the student of the past mayregret this in some measure if it depriveshim of information he wishes to acquire.

The first London founders of note werea family of the name of Wymbish, residingin Aldgate, which was always the bell-founders’quarter, as the still existing nameof Billiter (or Belleyetere) Street implies.There were three Wymbishes—Richard,Michael, and Walter—covering the period1290–1310. Richard cast bells for theneighbouring Priory of the Holy Trinity,and has left his name at Goring, in Oxfordshire,and on other bells in Essex, Kent,Northants, and Suffolk; Michael cast fivebells still remaining in Bucks; and Walter,one in Sussex. Other important foundersof this century are Peter de Weston,William Revel, and William Burford.[Pg 25][2]John and William Rufford, who may havehad their foundry at Bedford, were knownas “Royal bell-founders,” and placed upontheir bells the heads of the reigning King,Edward III, and his consort, Philippa.These stamps have a very curious history;and were successively the property offounders at King’s Lynn, Worcester, Leicester,and Nottingham. At the latterplace they remained in use from about1400 down to the end of the eighteenthcentury; and their last appearance is in1806, on a bell at Waltham Abbey, castby Briant of Hertford.

Between 1370 and 1385 there was afounder in Kent whose name was StephenNorton; he used very richly-ornamentedletters, which may be seen on one of theold bells of Worcester Cathedral, cast byhim when the tower was rebuilt. Theother principal foundries of this centurywere at King’s Lynn, Gloucester, andYork.

The Gloucester foundry was successively[Pg 26]in the hands of “Sandre of Gloucester”(1300–1320) and “Master John of Gloucester”(1340–1350). The latter’s reputationapparently extended to East Anglia,as in 1347 he was commissioned to castsix new bells for the Cathedral at Ely,which were conveyed thither from Northamptonby way of the Nene and Ouse.The largest bell, called “Iesvs,” weighednearly two tons, and the fourth was named“Walsingham,” after the famous PriorAlan who constructed the central octagonof the cathedral.

Of the York founders, the most famousis Richard Tunnoc, commemorated in theremarkable “Bell-founder’s window” alreadydescribed (Plate13). He was M.P.for the city in 1327, and died in 1330.The names of other known founders ofthis city extend from Johannes de Copgrave,in 1150, down to the time of theReformation. A bell at Scawton, in theNorth Riding, has been thought to bethe work of Copgrave, and, if so, is by[Pg 28]far the earliest existing church bell inEngland, if not in Europe.

In the fifteenth century (with which wemay include the whole period down to theReformation) the bell-foundries increasenot only in importance but in numbers;and those already mentioned find rivalsspringing up at Reading and Wokingham,Exeter, Bristol, Leicester, Norwich, Nottingham,Bury St. Edmunds, Salisbury, andWorcester. The character of the inscriptionsnow changes, and in most cases(though not invariably) we find “black-lettersmalls,” with initial capitals, substitutedfor the old Gothic capitals usedthroughout. There is also a great increasein the number and variety of the crossesand other ornamental devices used by thefounders, and many introduce foundry-shieldsor trade-marks, with quasi-heraldicor punning devices.

The London foundries, however, stillmaintain their place at the head of thecraft, and their bells are found all over[Pg 29]England from Northumberland to Cornwall.Two founders of the fifteenth century,Henry Jordan and John Danyell,whose date is about 1450–1470, castbetween them about two hundred bellsstill existing. These are adorned withsome beautiful and ingenious devices, suchas an elegant cross surrounded by thewordsihu merci ladi help (Plate14) andthe Royal Arms surmounted by a crown.Jordan’s foundry-shield bears, among otherdevices, a bell and a laver-pot as symbolicalof his trade, and a dolphin with referenceto his membership of the Fishmongers’Company. Another remarkable device(Plate14) is that used by William Culverden(1510–1523), with a rebus on hisname (culver = “pigeon”). ThomasBullisdon is remarkable as having cast aring of five bells for the Priory ofS. Bartholomew in Smithfield about 1510,all of which still exist there.

To tell of the works of Roger Landenof Wokingham, Robert Hendley of Glou[Pg 30]cester,John of Stafford (a Leicesterfounder), Robert Norton of Exeter, orthe Brasyers of Norwich, would requirea volume. I can only note some interestingfeatures of their work. The Brasyersseem to have been the most successfulworkers outside London, and no less thanone hundred and fifty of their bells stillexist in Norfolk. Their trade-mark wasa shield with three bells and a crown,which after the Reformation went to theLeicester foundry, and some of their inscriptions,in rhyming hexameters, are verybeautiful. A Bristol founder of about1450 used for his mark a ship, the badgeof his native city. The Bury founderswere also gun-makers, and place on theirtrade-mark a bell and a cannon, with thecrown and crossed arrows of S. Edmund.

Moulds ready for casting.

The inner and outer moulds clamped together; the molten metal is poured inthrough an aperture at the top. (See page14.)

Very few bells of this period are dated;but we find examples at Worcester, perhapscast by the monks there, with thedates 1480 and 1482; and at Thirsk(1410), on a bell which is said to have[Pg 32]come from Fountains Abbey. There arealso some bells in Lincolnshire, dated 1423and 1431, by an unknown founder, butremarkable for the extraordinary beauty ofthe lettering (Plate36). Dated mediaevalbells are more commonly from foreignsources, as at Baschurch, in Shropshire,where is a Dutch bell by Jan van Venlo,dated 1447, which is said to have comefrom Valle Crucis Abbey. At WhalleyAbbey, in Lancashire, is a Belgian bell of1537, by Peter van den Ghein, and at Duncton,in Sussex, a French bell dated 1369.

The period of the Reformation, downto about 1600, was, as has been said,“a real bad time for bell-founders,” andseveral of the important foundries, as atBristol, Gloucester, and elsewhere, appeareither to have been closed for a time ordied out altogether. The chief cause ofthis was doubtless the dissolution of themonasteries, coupled with the operations ofEdward VI’s commissioners, large numbersof bells being sold or converted into secular[Pg 33]property. These were distributed amongthe parish churches, and many instancesmay be traced of second-hand bells stillexisting, as at Abberley, in Worcestershire,where there is an ancient bell froma Yorkshire monastery. It should alsobe remembered that very little church-buildingwas done in the latter half of thecentury. On the other hand, the statementwhich has gained some currency,that the commissioners only left one bellin each parish church, is not borne out byfacts. Many churches still possess threeor even four mediaeval bells which musthave hung untouched in their towersbefore and since the reign of Edward VI.

But this lapse in bell-founding was notinvariable; the foundries at Leicester, Nottingham,Bury St. Edmunds, and Readingactually seem to have received a new leaseof life, and 1560–1600 is almost their mostflourishing period. This is especially thecase at Leicester, where a well-knownfamily named Newcombe were at work,[Pg 34]succeeded by an equally celebrated foundernamed Hugh Watts, whose fine bells weredeservedly famous. At Nottingham wehave the dynasty of the Oldfields, lastingfrom 1550 to 1710; and at Readinga series of founders of different names,ending in a succession of Knights downto 1700. The Hatches of Ulcombe, inKent, were another prosperous family, aswere the Eldridges of Chertsey.

At Bury St. Edmunds, one StephenTonne reigned from 1560 to 1580. Hisfoundry was, however, destined to yieldto the sway of that at Colchester, whichbegins with Richard Bowler about 1590,and reached its culmination between 1620and 1640, under the great Miles Graye,who has been called “the prince of bell-founders.”Numbers of his bells remainin Essex and Suffolk, his masterpiece being,by common consent of ringers, the tenorat Lavenham, in Suffolk. At Colchester,as in other foundries, the seven years ofstorm and stress—1642–1649—while the[Pg 36]Civil War between Charles I and theParliament raged in England, practicallyput an end to bell-founding. Siege andother troubles certainly hastened the endof old Miles Graye, who died in 1649,worn out by privation and bodily suffering.His grandson Miles kept on thefoundry until 1686.

Turning to the West of England, wefind the foundries at Bristol, Gloucester,Worcester, and Salisbury still in a flourishingcondition. At Bristol George Purdue,a native of Taunton, was followed byRoger and William Purdue in the seventeenthcentury; the latter migrated toSalisbury about 1655, where he carried onthe work of John Wallis and John Danton.Thomas Purdue, the last of the family,died at Closworth, in Somerset, in 1711,and on his tombstone are the words—

In the West of England their place was[Pg 37]filled by the Penningtons of Exeter, theEvanses of Chepstow, and the Bilbies ofChew-Stoke, Somerset. The Keenes ofBedford and Woodstock, John Palmer ofGloucester, and John Martin of Worcester,all did good work in their day, asdid the Cliburys of Wellington, in Shropshire.Another important Midland firmwas that of the Bagleys, of Chacomb, inNorthamptonshire, whose foundry wasopened in 1631, and flourished till theend of the eighteenth century; though inthe latter period its owners became restless,and settled temporarily in London, Witney,and other places. In the North, Yorkwas again the chief bell-founding centre,and Samuel Smith and the Sellers werefamous exponents of the art; in the Eastof England we have, besides Miles Graye,first the Brends of Norwich, then JohnDarbie of Ipswich, and Thomas Gardinerof Sudbury.

Several founders between 1560 and1700 were mere journeymen, who went[Pg 38]about from place to place, doing jobswhere they could. Of such was MichaelDarbie, of whom it is said, “one specimenof his casting seems to have been enoughfor a neighbourhood.” At Blewbury, inBerkshire, a local man attempted to recasta bell in 1825. He failed twice, but wasthen successful, and placed on his workthe appropriate motto,Nil desperandum.Apart from this, it was not at all uncommonfor bells to be cast on the spot, as wereGreat Tom of Lincoln and the great bellof Canterbury, or at some convenient intermediateplace.

In 1684 a fresh start was given to theGloucester foundry, then fallen on baddays, by Abraham Rudhall, perhaps themost successful founder England hasknown. He and his descendants castaltogether 4,521 bells down to 1830, andtheir fame spread all over the West ofEngland, from Cornwall to Lancashire,and even over the seas. Most of the bigrings of bells in the West Midlands are[Pg 40]their work. The foundry finally came toan end in 1835, when the business wasbought up by Mears of London.

In London itself bell-founding seemsto have come almost to an end between1530 and 1570. But about the latteryear arose one Robert Mot, who set onfoot what is now the oldest-establishedbusiness of any kind in England. Thefoundry in the Whitechapel Road, nowonly a short distance removed from itsoriginal home, has always upheld its reputationthroughout the three hundred yearsand more during which it has been continuouslyworked. Several of Mot’s bellsstill remain in London, and many others inKent and Essex (Plate15). In the seventeenthcentury the foundry was in thehands of Anthony and James Bartlet, whocast many bells for Wren’s churches afterthe Great Fire. In the eighteenth, underPhelps, Lester, Pack, and Chapman, successively,its reputation gradually increased,and in 1783 began a dynasty of Mearses[Pg 41]lasting down to 1870. The name is stillpreserved by the firm of Mears and Stainbank,though neither a Mears nor a Stainbanknow owns a share in the business.An illustration of their bells is givenin Plate16.

Their great rivals of modern times, theTaylors of Loughborough, cannot emulatethem in antiquity, though they can stillboast a respectable pedigree, dating fromThomas Eayre of Kettering, in 1731.After moving to S. Neots, Leicester, andOxford, the firm finally settled, about1840, under John Taylor, at Loughborough,where his grandsons now carryon the business. Illustrations of theirbells are given in Plates17–21.

Bells of exceptional size, styled inLatinSigna, are no new inventionof the founder’s art. It speaks much forthe skill of the mediaeval craftsman thathe should have been able to cast giantbells which not only rivalled thechefs-d’oeuvreof our own day, but, as objectsof beauty, certainly surpassed them.

In the twelfth century a “tenor” wasadded by Prior Wybert to Prior Conrad’sgreat ring of five at Canterbury Cathedral,which bell, it is said, took thirty-two mento ring it. (This was achieved by placingthem on a plank fastened to a stock, bywhich means it was set in motion.) It[Pg 44]was, however, surpassed by another castin 1316, in memory of S. Thomas ofCanterbury. This weighed over 3½ tons,but was broken in the fall of the campanile,1382, and was replaced in 1459by a slightly heavier bell, cast in London,and dedicated in honour of S. Dunstan.Its successor, a re-casting by Lester andPack of London, in 1762, stills hangs inthe south-west tower, and is used for theclock and for tolling.

The cathedral of Exeter was furnishedwith two bells which deserve the title ofgreat; but one, the tenor of the old ringof seven, does not strictly come within thelimits of this chapter, which deals withsingle bells. All these old bells hadnames, some derived from their donors,and the tenor was called Grandison, fromthe bishop by whom it was given about1360. Its successor, cast in 1902, byTaylor of Loughborough, weighs about3 tons (Plate18). The other, Great Peterof Exeter, hangs in the north tower, and[Pg 45]was the gift of Bishop Peter (Courtenay)in 1484. It has been twice re-cast, and thepresent bell is the work of the Thomas Purduementioned in the previous chapter,dated 1676. The founder attempted topreserve the old mediaeval inscription,

Plebs patriæ plaudit dum petrumplenius audit

“The people of the country applaud when they hearPeter’s full sound,”

but only found room for the first fivewords. From the style of the inscriptionwe gather that it was originally cast at theExeter foundry. Its weight is given as6¼ tons, but according to another estimateis not more than four.

There is a rival “Great Peter” atGloucester, and here the original bell stillsurvives, the only mediaevalsignum whichwe still possess. It bears the inscription,

Me fecit fieri conventus nomine petri

“The monastery had me made in Peter’s name,”

together with two shields, one chargedwith three bells, the other with the armsof the abbey. It may have been cast bythe monks, as it bears no known foundry-stamps,but the expression “had memade” seems to imply otherwise. Itsweight is 2 tons 18 cwt. Yet another,but a modern “Great Peter,” is that ofYork Minster, cast in 1845, and weighing12½ tons. It is the second largest churchbell in England.

Bell by an early fourteenth-century Londonfounder.

With inscription in Gothic capitals. (See page24.)

From “Great Peters” we pass to “GreatToms.” Of these there are two famousexamples, one at Lincoln Cathedral, theother at Christ Church, Oxford. TheLincoln Tom, which hangs in the centraltower of the cathedral, does not appear inrecords before 1610, in which year it wasre-cast by Henry Oldfield of Nottingham,and Robert Newcombe of Leicester. Itwas cast in the minster yard, and weighed4 tons 8 cwt. In course of time it wasfound to be too heavy for the tower,and was “clocked,” or tied down, as[Pg 48]a contemporary journalist describes it,in 1802: “He has been chained andriveted down, so that instead of thefull mouthful he hath been used tosend forth, he is enjoined in the futuremerely to wag his tongue.” The resultwas inevitable, and in 1827 “he” wasreported cracked, which led to his beingre-cast by Mears of Whitechapel in1835.

Great Tom of Christ Church, which nowhangs in the tower over the gateway,originally came to the newly-founded“House of Christ” from the despoiledAbbey of Oseney. Six other bells werebrought with it, of which two still hang inthe “meat-safe” belfry. Antony à Wood,the Oxford chronicler, tells us that it borethe inscription:

IN THOMAE LAVDE RESONO BIMBOM SINEFRAVDE

“In the praise of Thomas I sound ‘Bimbom’ withoutguile.”

Thrice unsuccessfully recast between1612 and 1680, it is in its presentform the work of Christopher Hodson,a London founder, who placed uponit a long inscription beginning withthe words,MAGNUS THOMAS (“GreatTom”). Oxonians will remember theringing of the bell every night at nineo’clock.

Among other great bells of historicalinterest we may mention that which hangsin the south tower of Beverley Minster.It survived from mediaeval times until sorecent a date as 1902, when it was re-castby Messrs. Taylor of Loughborough theweight being no less than 7 tons (Plate19).The old bell was probably cast at Leicesterabout 1350, and bore some of the mostbeautiful lettering ever designed by mediaevalcraftsmen (Plate36). Another ofMessrs. Taylor’s great works is the greatbell of Tong, in Shropshire (Plate20),originally given by Sir Harry Vernon, in1518, to be tolled “when any Vernon[Pg 50]came to Tong.” It was recast in 1720,and again in 1892, its present weightbeing 2½ tons. It was dedicated to SS.Mary and Bartholomew.

Another great mediaeval bell, only recentlyrecast, deserves mention here, thoughstrictly speaking, the tenor of a ring, andnot asignum. This is the magnificenttenor at Brailes, in Warwickshire, richlyornamented with shields, crowns, and otherdevices, cast by John Bird of London,about 1420. It bore a beautiful inscriptiontaken from an old Ascension Dayhymn. Greatly to the credit of the localauthorities, the inscription and ornamentswere exactly reproduced from the oldcracked bell on its successor, an admirablepiece of work executed in 1877 byMessrs. Blews of Birmingham. The bellweighs about 2 tons.

Among great modern bells the hour-bellat Worcester Cathedral, cast by Taylorin 1868, and weighing 4½ tons, deservesspecial mention, as does a bell at Woburn,[Pg 52]Bedfordshire, the work of Mears andStainbank of London, in 1867, weighingnearly 3 tons. The former bears an inscriptiontaken from Ephesians v. 14, andthe letters used are copied from those onthe beautiful Lincolnshire fifteenth-centurybells mentioned in the previous chapter (p.32). But the chief masterpiece of recentfounding is Messrs. Taylor’s “GreatPaul” at S. Paul’s Cathedral, whichholds the reputation of the largest bellin England (Plate21). It has, however,a rival in the hour-bell of the samecathedral, which has a more lengthyhistory. There was once at Westminstera famous bell known as “GreatTom,” which hung in a clock-tower oppositeWestminster Town Hall, but wasremoved to S. Paul’s at the end of theseventeenth century. This bell was famousfor its connection with the story told of asentinel at Windsor Castle in the reign ofWilliam III, who was accused of sleepingat his post. He defended himself by[Pg 53]stating that he had heard the Westminsterbell strike thirteen at midnight, and thisbrought about his acquittal. Though thetruth of the story has often been doubted,the striking thirteen is, mechanically, quitepossible. It is said that this bell wasoriginally given by Edward III in honourof the Confessor. On the way to S. Paul’sit was cracked by a fall, and eventuallyit was recast by Richard Phelps,of Whitechapel, in 1716 (Plate22).It now hangs in the south-west tower,and is used for striking the hour, andfor tolling at the death of variousgreat personages. Its weight is 5 tons4 cwt.

Great Paul is the masterpiece of Messrs.Taylor, “one of Loughborough’s glories,”says Dr. Raven. It hangs in the sametower, below Phelps’ bell, and weighs16 tons 14 cwt., the diameter at themouth being 9½ feet. It was cast in1881, and simply bears the founders’trade-mark and the words (said to have[Pg 55]been selected by Canon Liddon) from1 Corinthians ix. 16:

VAE MIHI SI NON EVANGELISAVERO

“Woe unto me if I preach not the Gospel.”

It is used for a few minutes before Sundayservices, and at certain other times.

A description of S. Paul’s bells is hardlycomplete without an allusion to the greatring of twelve cast by Taylor in 1877, andplaced in the north-west tower, the tenorweighing over 3 tons. They were givenby the City Companies and the lateBaroness Burdett-Coutts. In additionthere are a “service bell,” cast in 1700,and two quarter-bells of 1717 for theclock.

Among other great London bells arethe ring of ten at the Imperial Institute,cast by Taylor in 1887, and the tenors ofthe rings at Southwark Cathedral, S. Mary-le-Bow,S. Michael, Cornhill, S. Giles,Cripplegate, and other famous towers;[Pg 56]those mentioned are all from rings oftwelve, and weigh 2 tons or more.

The old campanile at Westminster, builtby Edward III, originally contained three“great bells”; it was pulled down in1698, and we have followed the historyof one of these bells, but the others disappeared.They had no successor until1856, when the late Lord Grimthorpe(then Mr. Denison), an enthusiast forclocks and bells, designed a great bell forthe clock tower of the Houses of Parliament.It was called “Big Ben,” eitherafter Sir Benjamin Hall, who was thenFirst Commissioner of Works, or after anoted boxer of the time named BenjaminBrain. Its original founders were Messrs.Warner of London, but being sounded inPalace Yard with a hammer, for the amusementof the public before being hung, itwas very soon cracked. In 1857 a new bellwas cast by George Mears of Whitechapel,from an improved design, andcontaining less metal. Its weight is given[Pg 57]at 13½ tons. Shortly after its casting BigBen gave way, but after being quarter-turned,could be once more utilized forstriking the hours. Its tone, however, isanything but satisfactory, and one is forcedto the opinion that these excessively largebells, very difficult to cast and awkward tomanipulate, are apt to prove great mistakes.

Chimes

Sets of chimes, or arrangements for playingtunes on bells, existed in England evenin mediaeval days; but they are nowadaysregarded as a speciality of Belgium, andthe famous carillons of Antwerp, Bruges,and Mechlin are well known to many atraveller. But it is not our province tospeak of these, and it may be of someinterest to see what use has been madeof such arrangements in England.

Dr. Raven, in his fascinating book,TheBells of England, tells us that the machineryof the carillon was a recognized thing in[Pg 58]the middle of the fifteenth century, andquotes from the will of John Baret ofBury St. Edmunds, who died in 1463,and gave directions for the playing of aRequiem aeternum for his dirge at noonfor thirty days after his death, and oneach “mind-day,” or anniversary, to becontinued during the octave. The sextonwas also to “take heed to the chimes andwind up the pegs and the plummets” asrequired. The music of thisRequiem, weare told, only compassed five notes, andmust have been somewhat wearisome tothe good people of Bury. In old churchwardens’accounts, as at Ludlow or Warwick,we find frequent references to therepair or upkeep of the chimes.

Bell by Robert Mot of London (1575–1600),

The first owner of the Whitechapel Foundry, where it had been for some yearspreserved, but is now broken up. (See page40).

The principle of the carillon is similarto that of a barrel-organ or musical-box,implying a barrel or drum, set with pegs,and set in motion by being connected withthe mechanism of the clock. The pegs, asthey turn, raise levers which pull wires inconnection with the hammers which strike[Pg 60]on the bells. With the ordinary eightbells of an English belfry it is obviousthat only a limited choice of tunes withinthe compass of an octave is possible, andthat they can only be played in one keyon single notes. The Belgian carillonshave sometimes forty or fifty bells in communicationwith a key-board like that ofan organ, and tunes can therefore be playedon them in harmony. There are a fewcarillons of this type in England, the bestknown being at Boston, in Lincolnshire,and at Cattistock, in Dorset, but usuallythe ordinary bells are employed, as atWorcester Cathedral and in many towns.

At the Reformation chimes largely diedout, but with the Restoration they revived,and we hear of them at Cambridge,Grantham, and elsewhere. Another kindof chime which may here be mentioned isthat employed for striking the quarters forthe clock. Here, of course, no mechanismis required beyond the connecting-wirewhich raises the hammer and drops it on[Pg 61]the bell. Of such chimes the best knownare the Cambridge Quarters, put up inGreat S. Mary’s Church in 1793. Theywere composed by Dr. Jowett, the RegiusProfessor of Laws, assisted by the composerCrotch, who was then only eighteen.The latter is said to have adapted a movementin the opening symphony of Handel’s“I know that my Redeemer liveth,” forthe purpose.

The practice sometimes adopted nowadaysof playing hymn tunes on bells bymeans of ropes tied to the clappers is amiserable substitute for the mechanicalcontrivance. It not only causes agonies tothe musical ear by the unavoidable occurrenceof false notes, but is only too likelyto lead to the destruction of the bells altogether,as the result of the “clocking,” ofwhich I shall have more to say later.

Campaniles

We have seen that it is the normal rulein England for bells to be placed in towers[Pg 62]forming part of the structure of churches;or rather it should be said that towers forcontaining the bells were regarded as anessential feature in the construction of achurch from the Saxon period onwards.Over the greater part of the Continent thesame also holds good; but in Italy we finddetached bell-towers, or campaniles, to beof frequent occurrence. The most familiarexamples in that country are the campanileof S. Mark’s at Venice, and that built byGiotto at Florence. There are many othersin Northern Italy, especially at Bologna,and at Ravenna, where the churches areof great antiquity.[3]

A ring of eight bells.

Recently cast at the Whitechapel Foundry for Uckfield, Sussex. (See page41).

Nor are such campaniles altogether unknownin England. In mediaeval timesthey were attached to several of ourcathedral churches, as, for instance, OldS. Paul’s, Chichester, Salisbury, and Worcester.The bells of Old S. Paul’s weretraditionally gambled away by Henry VIIIin 1534, and the campanile at Worcester[Pg 64]did not survive the Reformation; but thatat Salisbury, a most picturesque structure,with a wooden upper storey and spire, waswantonly destroyed in 1777 because thebells were misused! That at Chichesteralone remains, a fine Perpendicular erection,at the north-west angle of thecathedral (Plate24). At King’s College,Cambridge, a noble peal of five bellshung in a low wooden belfry on thenorth side of the chapel, which wasdestroyed when the bells were sold andmelted down in 1754 (Plate25).

Detached towers are not uncommonfeatures of our parish churches in someparts of England, particularly in Herefordshireand Norfolk. The best examplesare at Berkeley, Gloucestershire; Ledbury,Herefordshire; West Walton, Norfolk;and Beccles, Suffolk. Some churches,again, can only boast wooden detachedbelfries of moderate height to hold theirbells, as at Pembridge in Herefordshire,Brooklands in Kent, and East Bergholt in[Pg 65]Suffolk (Plate26). The belfry at the last-namedplace is no more than a mere shed,and more than one story is told in explanationof the absence of a tower to theotherwise imposing church.

One of the chief uses made of churchbells in modern times is not strictlya religious use, though it is more or lessassociated with the Church’s seasons, particularlywith Sundays and Christmas Day.But it has always been recognized thatthe secular use of bells, within certainlimits, is permissible, as will be furtherseen in the next chapter.

Change-ringing is, as we have alreadynoted, an entirely modern introduction,and is, moreover, confined to England.In pre-Reformation days we hear of guildsof ringers, as, for instance, at WestminsterAbbey, in the reign of Henry III, wherethe brethren of the guild appear to haveenjoyed their privileges since the time of[Pg 68]Edward the Confessor. In smaller monasticor collegiate establishments clerics inminor orders were often entrusted withthe duty of ringing the bells, as at Tong,in Shropshire (cf. Plate30). But this kindof ringing was in no way scientific, norwere the fittings of the bells adapted forringing in the strict modern sense.

The accompanying diagram (Plate27;compare also Plate28), showing the wayin which a modern bell is hung, willserve to explain the method now adoptedfor ringing proper, as opposed to chiming.The headstock, or wooden block to whichthe top of the bell is firmly fixed (so thatthe bell cannot move independently of it),revolves by means of brass pivots, knownas the “gudgeons,” in a socket made inthe top of the framework. One of thesepivots forms the axle of a large woodenwheel, half the circumference of which hasa groove for the rope, one end of which isfixed in it, the other passing through apulley down into the ringing-chamber. In[Pg 69]mediaeval times half-wheels only were used,but the complete wheel seems to have beenintroduced by the fifteenth century, andsingle bells were “rung” in the sixteenth.Peal-ringing, as we know it, cannot betraced before the seventeenth.

The essential feature of ringing in pealis that the bell shall perform an almostcomplete revolution each time the rope ispulled, starting from an inverted position.To prevent its falling over again at theconclusion of the stroke, a vertical bar ofwood or iron, known as the “stay,” isfixed to the side of the stock, which ischecked by a movable bar in the lowerpart of the frame, called the “slider.” Itis clear that in the course of each revolutionthe clapper will strike the side twice.Before the invention of the wheel, the bellwas merely sounded by means of a lever connectingthe rope with the stock, as is stilldone in ringing small bells, either as “ting-tangs,”or when hung in an open turret.

Before the peal can be started, the bells[Pg 70]must be rung up or “raised” to the invertedposition, which the ringer achievesby a series of steady strokes, each pullincreasing in length until it is balanced;at the end of the peal this process is reversed.When bells are merely chimedthey are not “raised,” but the rope ispulled each time sufficiently to allow onestroke of the clapper. By means of aningenious apparatus invented by the lateCanon Ellacombe, this can now be done byone man if necessary, the muscular effortrequired being reduced to a minimum.

But change-ringing is a real science, andentails long and assiduous practice and considerablemuscular exertion. It is, in fact,one of the best forms of physical exerciseconceivable, and must have proved a godsendin that respect to many men whoseopportunities would otherwise be limited.

Its elementary principle is, of course,that the bells should be rung in succession,but in a varying order. The method inwhich the succession varies is the founda[Pg 71]tionof the various forms known vaguelyto most of us as Grandsire Triples, TrebleBob-Major, and so on. They are foundedon a recognized arithmetical basis, that ofpermutations, or the number of arrangementspossible of any given number ofobjects. We know that three letters ornumbers can be arranged in six differentways:

123 132

231 213

312 321

Thus, on three bells, only six changes canbe rung so as to vary the order each time,and we must then begin over again. Withfour bells we have a choice of twenty-fourchanges, which might run as follows:

1234 3124 4321 4213

2134 1324 4312 4231

2314 1342 4132 2431

2341 3142 1432 2413

3241 3412 1423 2143

3214 3421 4123 1243

This method is known as “hunting thetreble up and down,” and was invented byFabian Stedman, a Cambridge printer, whoprinted in 1667 the earliest treatise onchange-ringing. If the above table is carefullyobserved, it will be seen that the firstbell, or treble, shifts its place by one eachtime, backwards or forwards, while theother three only change six times in all;in other words, if the treble was omittedit would be a peal of six changes on threebells.

The tenor bell of Exeter Cathedral, called“Grandison.”

Recast by Taylor, 1902. (See page44.)

When we come to rings of five, six, oreight bells, these changes are, of course,capable of greater variety. On five bellswe may have 5 times 24, or 120 changes;on six, 6 times 120, or 720; on eightbells, 40,320; and so on. But in actualpractice it is very rare to have more thanfive or six thousand rung, even if thereare eight or more bells; about 1,600changes can be rung in the course of anhour, and two to three hours’ consecutivework is as much as an ordinary ringer is[Pg 74]capable of accomplishing. The essentialfeature of each set of changes is to bringthe bells round to the order in which theystarted; as they would naturally do in thepeal given above.

The result of the introduction of systematicand organized change-ringing wasthat companies or societies of ringers werevery soon formed. So early as 1603 wehear of a company known as the “Scholarsof Cheapside,” formed in London. In1637 was founded a famous LondonSociety, that of the “College Youths,”probably a revival of the one just named;its name is derived from some connectionwith Sir Richard Whittington’s College ofthe Holy Ghost, near Cannon Street. Itwas to them that Stedman dedicated hisTintinnalogia, the work already mentioned.There is still an energetic “Ancient Societyof College Youths,” but it is not certainwhether it can trace an actual descent fromthe older society. Another well-knownringing society is that of the “Cumberland[Pg 75]Youths,” originally “London Scholars,”who changed their name in 1746 in complimentto the victor of Culloden.

Before leaving the subject, may I venturehere a protest against the absurditiesperpetrated by the artists of Christmascards and illustrated magazines, in theattempt to render the form of a bell andthe method in which it is rung? It iscertain that few can ever have visited eitherbelfry or ringing-chamber! Plate29 givesa more truthful rendering of the methodof ringing.

It may be fairly claimed as one of thefar-reaching effects of the Church Revivalthat the conditions of our belfries and theconduct of our ringers will compare veryfavourably with what it was some forty orfifty years ago. Where the more accessibleportions of the fabric were given over todirt and neglect, and slovenliness was thechief feature of all ordinary forms of worship,it was hardly surprising that thetowers and their internal arrangements[Pg 76]were neglected, and frequently given overto more secular uses.

Nor was this merely a result of thegeneral laxity and indifference of the“dead” period in the Church. Thereare not wanting signs that in the seventeenthcentury the standard of disciplineamong ringers was not high. We mayrecall how John Bunyan, at one time anenthusiastic member of the ringing companyof Elstow, was constrained to abandonthe pursuit, along with other enjoyments,as not tending to edification. That convivialityreigned in the belfry in those daysis shown by the use of ringers’ jugs, someof which still exist, in which large quantitiesof beer were provided, and by thefrequent entries in parish accounts ofmoney spent on beer for the ringers.One of the bells at Walsgrave, in Warwickshire(dated 1702) has the inscription:

evidently intended for a gentle hint thatthe ringers suffered from thirst!

At the same time there was a feelingthat the actual ringing should be properlycarried out, which finds vent in the numerous“Ringers’ Rules,” mostly dating fromthe eighteenth century, which may be seenpainted up on the walls of our belfries.They all follow very much on one pattern,and one of the best versions is at Tong,in Shropshire, which may be given as anexample—

It is satisfactory to note that the ruleagainst swearing was very generally included,though possibly honoured morein the breach than the observance; but itis probable that the objection to wearing ahat was more on the grounds of inconvenienceto the ringers than of irreverence.

As late as 1857, the Rev. W. C. Lukis,one of the earliest writers on church bells,complained of his own county, Wiltshire,that “there are sets of men who ring forwhat they can get, which they consume indrink; but there is very little love for thescience or its music; and alas! muchirreverence and profanation of the HouseofGod. There is no ‘plucking at thebells’ for recreation and exercise. Church-ringerswith us have degenerated into[Pg 80]mercenary performers. In more than oneparish where there are beautiful bells, Iwas told that the village youths took nointerest whatever in bell-ringing, and hadno desire to enter upon change-ringing.”

Although less money is available nowadaysfor payments to ringers on specialoccasions, it may be feared that theseremarks still hold good to some extent.But in other respects there is undoubtedimprovement. We do not now hear of“prize-ringing,” or ringing in celebrationof a victory in the Derby or in aparliamentary election, and if our ringing-chambersdo not always reach a highstandard of decency, there is a markedimprovement in the character and behaviourof the ringers themselves.

An old monkish rhyme sums up theancient uses of bells as follows:—

which may be rendered in English:—

These lines will be familiar to readersof Longfellow’sGolden Legend; but someof the uses mentioned belong to a timewhen bells were thought to have a magicpower over the forces of nature, and acategory of modern uses embraces manyothers here ignored.

The modern uses of bells naturally fallinto two main divisions—religious andsecular, or quasi-religious uses. By theformer I mean the ringing of bells fordivine service, and, in particular, for thefestivals of the Church, and their use atweddings, funerals, and other events oflife with which the Church is naturallyconcerned. Other uses, again, thoughnow purely secular, had once a religiousmeaning, such as the Curfew and Pancakebells. More secular uses are those of theGleaning bell and the Fire bell, of bellsrung for local meetings or festivities, or incommemoration of national events.

The only allusion to bells in our PrayerBook is in the Preface, which directs that[Pg 84]the minister “shall cause a bell to betolled thereunto a convenient time beforehe begin, that the people may come tohearGod’s Word, and to pray with him.”This was, of course, the original purposefor which bells were applied to an ecclesiasticaluse, and by virtue of which theyare reckoned among the “Ornaments ofthe Church.” It is, therefore, the rulethat every place of worship within therealm of the Church should have at leastone bell, and in England at any rate thereare not more than half a dozen parisheswhere the rule is ignored. The fifteenthCanon similarly enjoins the ringing of abell on Wednesdays and Fridays for theLitany.

Methods of ringing the bells for servicedepend largely on the number of bellsavailable and the possibility of collectingringers together; and the ringing of pealsat these times is comparatively rare. Ordinarily,where there are more than two, thebells are chimed for periods varying from[Pg 85]ten minutes to half an hour on Sundays,while on week-days a single bell perforcesuffices, tolled haply by the parson himself.In many places it is the custom totoll the largest bell for the last few minutesbefore service begins; this is known as the“Sermon Bell,” and was originally meant toindicate that a sermon would be preached.Or the smallest bell is rung hurriedly, asif to warn laggards, and this is called the“ting-tang,” “priest’s,” or “parson’s”bell. Some of these little bells bear theappropriate inscription, “Come away makeno delay.” The use of a sermon bell issaid to date from before the Reformation.

In many parishes it used to be an invariablecustom to ring a single bell, orchime several, at eight o’clock on Sundaymorning; this, however, has lost its originalsignificance since the general introductionof early Celebrations. In formertimes the regular hour for Mattins was ateight, followed by Mass at the canonicalhour of nine, and though such an arrange[Pg 86]mentof services soon came to an end afterthe Reformation, the bells which used toannounce them were continued even downto the present day. There are still nota few parishes where a bell is rung at nineas well as at eight, even when there areno early services.

“Great Paul.”

Cast by Taylor, 1881. Now hanging in the south-west towerof S. Paul’s Cathedral. (See page52.)

In pre-Reformation days most churchespossessed, besides the regular “ring,”several smaller bells, which are describedin inventories as “saunce” or “sanctus”bells, “sacring bells,” and so on. Theiruses are sometimes confused nowadays,but were clearly defined. The sanctusbell, or saunce, usually hung in a turretor cot on the gable over the chancel arch,and was intended to announce the progressof the service to those outside who couldnot come to church. It was rung at thatpoint in the Sarum or English rites of theEucharist when the singing of theSanctusor “Holy, Holy, Holy,” just before theCanon of the Mass, was reached; whenceits name. The sacring-bell, on the other[Pg 88]hand, was much smaller, and hunginsidethe church, usually on the rood-screen.It was rung at the end of the ConsecrationPrayer, or “prayer of sacring” (Plate30),and announced the completion of the act ofsacrifice. The Reformers made a dead setagainst these practices, but it is difficult tosee that much superstition was involvedtherein, and the revival in modern days ofthe “sacring bell” in the form of a fewstrokes at the time of the consecrationhas more to recommend than to condemnit.

A few sacring bells still exist, hangingon rood-screens, in East Anglian churches,as at Salhouse and Scarning (Plate31),and one at Yelverton, in Norfolk, has justbeen restored to its old position. Ancientsanctus bells are more numerous, and afew still hang in their original cots, as atWrington, in Somerset, and Idbury, inOxfordshire (Plate32). They have mostlybeen fixed in the towers and used as “ting-tangs.”The majority have no inscription[Pg 89]on them, but there are notable exceptionsin some of the Midland counties.

The only other “Sunday use” to whichI have to draw attention is the ringing ofa bellafter services. This is, or was,sometimes done with the object of notifyinga service in the afternoon; but it isknown in some places, as at Mistley, inEssex, as the “Pudding Bell,” it beingsupposed that it was intended to warnhousewives to get ready the Sunday dinner!Some writers have thought thatthis midday bell is really a survival of themiddayAngelus, orAve bell; but it ismore likely to date from the bad times ofnon-residence and irregular services.

The ringing of bells on festivals is moreparticularly associated with Christmas andthe New Year, though the latter is asecular rather than a religious occasion.The Christmas bells have been a favouritetheme with poets, great and small, andthe best-known lines on the subject arein Tennyson’sIn Memoriam, said to have[Pg 90]been composed by him on hearing thebells of Waltham Abbey, in Essex (Plate33).

And again:

The more famous stanzas, beginning:

refer rather to New Year’s Eve.

On New Year’s Eve the old year isrung out and the new year in, in many[Pg 92]parishes. Sometimes one bell only istolled until the clock strikes twelve, inother cases the bells are rung muffled, i.e.,with the clappers wrapped round to deadenthe sound, these being uncovered at midnight,when a merry “open” peal burstsforth. Either practice is to be preferredto that of ringing consecutively before andafter the hour, which obscures the significanceof the performance.

The old “Great Tom” of Westminster.

Recast by Philip Wightman in 1698. From an olddrawing, made before its recasting by Phelps in 1716.(See page53.)

A muffled peal is sometimes rung onthe Holy Innocents’ Day, a custom saidto be kept up still in Herefordshire; andin addition to the Greater Festivals, theEpiphany, All Saints’ Day, S. Andrew’sDay, and S. Thomas’s Day, have been orare still specially honoured. Ringing onthe last-named occasion, which is kept upin several Warwickshire parishes, appearsto be associated with the distribution oflocal charities. But ringing on “superstitious”occasions, not mentioned in theBook of Common Prayer, is forbidden bythe 88th Canon.

Another day of the Church’s year withwhich bell-ringing is associated is ShroveTuesday, on which day the Pancake bellis rung in some places at eleven o’clock.Two bells are generally used, the sound ofwhich is supposed to resemble the word“pancake.” The origin of the custom isto be found in the calling of the faithfulto confess their sins and be “shriven” atthe beginning of the Lenten fast. Thatpancakes were associated with this day isdue to the fact that butter was forbiddenduring the whole of Lent. It was alwaysthe Church’s rule that the bells should besilent during that season—at least thatthere should be no peal-ringing in Lent,and no bells used at all during HolyWeek; and this is now generally observed.

Except in the case of royalty we seldomnow hear of bells being rung to ushermankind into the world; but they havealways been associated with the rejoicingsof a wedding ceremony, and in some[Pg 95]parts, as in Lincolnshire, are even rungat the putting up of Banns. But theiruse at the time of death is even moreuniversal.

The passing bell originally sounded asa summons to the faithful to pray for asoul just passing out of the world; but ithas now degenerated into a mere noticethat death has taken place, and as it isrung (to suit the sexton’s convenience)some hours after death, or even on thefollowing day, the name has ceased to beappropriate. It appears to be one of theoldest of all uses of bells, and is said tohave been rung for S. Hilda, of Whitby,in 680. Unlike most other customs itreceived the strong approval of the mostardent reformers, and in the churchwardens’accounts of the sixteenth andseventeenth centuries there are often longlists given every year of money receivedfrom parishioners “for the Knell.” Thesum paid was usually fourpence. The67th Canon directs that the passing bell[Pg 96]shall be tolled, “and the minister shallnot then slack to do his last duty.”

When the Knell is rung, it is a frequentpractice to indicate the age or sex of thedeceased. The former is done by tollinga number of strokes answering to theyears of his or her life, or more vaguelyby using the largest bell for an adult anda smaller for a child. Sex is sometimessimilarly indicated, but more usually bywhat are known as “tellers,” a varyingnumber of strokes for male or female, andsometimes also for a child. The commonestform is three times three for male,three times two for female; and sometimesthree times singly for a child; butsome parishes keep up curious variationsof this rule. The old saying “nine tailorsmake a man” is really “nine tellers,” orthree times three.

The knell with the tellers is sometimesrepeated at funerals, but more frequentlythe tenor bell is tolled at intervals of aminute, becoming more rapid when the[Pg 97]corpse appears in sight. In some countrydistricts the bells are or used to be chimedat this time, and in Shropshire this isknown as the “joy-bells,” or “ringing thedead home.” In olden days a hand-bellor “lych-bell” was rung before the corpseon its way; this is still done at Oxford atthe funeral of any University official.

Bells were largely used in mediaevaltimes to mark the hours of the day, evenbefore the introduction of clocks. In themonastic establishments they were naturallyrung at the canonical hours of twelve,three, six, and nine, for the services ofMattins, Lauds, Prime, Tierce, Sext, None,Vespers, and Compline. It has beensuggested that this is the reason whychimes are usually played at these hours,where there are carillons.

But one of the best known uses of bellsfor this purpose is the Curfew, which wasoften accompanied by a corresponding bellin the early morning. We have usuallybeen taught that the Curfew or “cover-fire”[Pg 98]was a tyrannical and unpopularenactment by William the Conqueror, andtherefore a purely legal and secular institution.There is, however, evidence that itwas in use long before at Oxford, whereKing Alfred directed that it should be rungevery evening (as it is still); and Williamprobably only made use of an existingcustom for the beneficent purpose ofguarding against fires.

But it has also been suggested that theCurfew was in its origin a bell with areligious as well as a secular significance,namely the Ave bell, or Angelus, whichwas rung in the early morning and theevening, usually at 9 a.m. and 5.30 p.m.,and also at midday, and at the sound ofwhich every one was expected to repeatthe memorial of the Incarnation or “HailMary.” Some have thought that bellsdedicated to the angel Gabriel werespecially devoted to such a purpose; butthis is doubtful, though the old Curfewbell at S. Albans still bears such a dedica[Pg 100]tion.At Mexborough, in Yorkshire, abell is rung morning, noon, and evening,obviously a survival of the Angelusbell.

The Curfew bell seems to have appealedespecially to poets, even to the AmericanLongfellow, and the puritan Milton, whoinIl Penseroso says:

Compare the opening line of Gray’sElegy:

“The curfew tolls the knell of parting day.”

The morning bell, whether an Ave bellor not, is seldom now rung, but may beheard at 5 a.m. at Ludlow, and at Nuneatonand Coleshill in Warwickshire. Oneof the old bells of S. Michael’s, Coventry,now at S. John’s Church in that town, hasthe inscription:

The Curfew bell, though alas! growingrapidly rarer, may be heard at 9 p.m. allthe year round in our two Universitytowns; and is also rung at eight atLudlow, Pershore, Shrewsbury, and inWarwickshire. But it is now usuallyconfined to the winter months, fromMichaelmas to Lady Day, or an evenshorter period. In some places the dayof the month is tolled afterwards, as atCambridge; at Oxford 101 strokes aregiven, representing the number of personson the foundation of Christ Church.

Of purely secular uses of bells spaceforbids me to say much. The Gleaningbell used to be rung in many parishesduring harvest, morning and evening, tosignify to the people when gleaning wasallowed. With the decay of agriculturein England this use has almost died out,especially in the midlands, but it is stillkept up in corn-growing parts, as in thenorth of Essex.

The old Campanile of King’s College, Cambridge.

Destroyed in the eighteenth century. It contained fivelarge bells. (See page64.)

Ringing has always been customary—at[Pg 103]least since the Reformation—on secularanniversaries, such as the birthday orCoronation Day of the Sovereign, or onthe occasion of great victories. It wasalso very common at one time on RestorationDay (May 29th), and GunpowderPlot Day (November 5th), but—perhapssince their removal from our Prayer Book—theseoccasions are becoming more andmore ignored. Ringing on November5th is, however, still common in Warwickshire.Another day on which ringingwas often practised was that of theparish feast, usually corresponding withthe patronal festival, or day on whichthe original dedication of the churchwas honoured.

It is or has been a tradition in someplaces that in cases of fire the church bellsshould be rung backwards; and elsewherea bell was specially devoted to this purpose.At S. Mary’s, Warwick, there is asmall fire bell dated 1670, which, however,is not now hung; and there is a well[Pg 104]-knownone at Sherborne, in Dorset, dated1653, with the inscription:

The large and small bells of the GuildChapel, Stratford-on-Avon, are also intendedto be rung in cases of fire.

The ringing of daily bells, especially atnight, is often accounted for by stories ofpeople who found their way when lost, orwere delivered from nocturnal dangers, byhearing the bell of some church. Instancesof this are scattered all over the country,and there are the Ashburnham bell atChelsea, the great bell of Tong in Shropshire,and others which were originallygiven in commemoration of such events,with the object of keeping up the ringingfor the benefit of other wanderers.

Most of us are probably aware thatit is usual for bells to bear inscriptions,be it only the date or name of themaker; but few who have not actuallyexamined bells for themselves may havediscovered that they are often richly oreffectively decorated. We do not as arule find them as highly ornamented asforeign bells, which often have everyavailable space covered with inscriptions,figures and devices, or borders of ornament;but to some the greater sobernessof the English method may seem preferable.Nor is this practice of ornamenting[Pg 106]bells confined to the more artistic agebefore the Reformation. Some of ourmost richly decorated bells belong to theseventeenth century or even later (seePlate38); and it is only the character ofthe ornamentation which is changed.

In point of fact the earliest bells areusually the plainest, and the mediaevalcraftsman contented himself with devotinghis skill to producing elegant and artisticlettering, beautiful initial crosses, or ingeniousfoundry marks (Plates14,36).The latter were introduced about theend of the fourteenth century, when, aswe have seen in an earlier chapter, theguild of braziers or “belleyeteres” weremore regularly organized. Those usedby Henry Jordan (see page29) are goodexamples; as are the shields of theBury and Norwich foundries (page30). Inthe West and North of England suchdevices are rarer; but badges, such asthe Bristol ship, or the Worcester “RoyalHeads,” take their place. One or two[Pg 108]of the London founders use the symbolsof the four Evangelists (Plate34). Afavourite device is the merchant’s mark,a kind of monogram, or the rebus, apictorial pun on the founder’s name.John Tonne, who worked in Sussex andEssex about 1520–1540, decorated hisbells in the French fashion, with largeflorid crosses, busts and figures, andother devices (Plate35).

Initial crosses are almost invariably foundon mediaeval bells, and their variety is endless,from the plainest form of Greekcross to the elaborate specimen shown onPlate36, which is found in the Midlandcounties. The words were frequentlydivided by stops, varying from a simplerow of three dots ⠇ to such devices as awheel, a rosette, or an ornamented oblongpanel. Impressions from coins pressedinto the mould are by no means uncommon.

But often the chief or sole beauty of amediaeval bell is its lettering. In the[Pg 109]fourteenth century this is invariably composedof capital letters throughout, ofthe ornamental form known as Gothic orLombardic (Plate36). Towards the endof that century the black-letter text usedin manuscripts was introduced into otherbranches of art, such as brasses, and thusalso makes its appearance on bells. Butthe initial letter of each word is stillexecuted in the old Gothic capitals, andsuch inscriptions are known as “MixedGothic” (Plate37), later ones of the sixteenthcentury being more strictly styled“black-letter,” where no capitals are used.The change, however, was not universal,and many of the foundries in the Westand North of England preferred to adhereto the capitals down to the Reformation;while even in London, as at Leicester,Reading, and elsewhere, there was a distinctrevival of inscriptions in capitalsduring the sixteenth century.

Diagram showing method of hanging abell for ringing (see page68).

| A. | Wheel with rope attached. |

| B. | Headstock. |

| CC. | Straps or Keys. |

| D. | Cannons (modern form). |

| E. | Stay. |

| FF. | Gudgeons. |

| G. | Brasses (in which the gudgeons revolve). |

| H. | Slider. |

The reign of Queen Elizabeth is usuallyregarded as a period of transition, and[Pg 111]there was, before the general introductionof modern Roman lettering, a time whenno general rule was observed. Somefounders used Gothic capitals; othersblack-letter; others again, nondescriptornate capitals difficult to classify; whilethe Roman lettering, introduced about1560–70, gradually ousted all the olderstyles from favour, and with very fewexceptions became general about 1620.The use of older lettering and stamps bymany founders during this “transition”period is noteworthy. The Leicesterfounders were especially addicted to thispractice, and among other old stampsbought up the beautiful lettering andornaments used by the Brasyers, of Norwich,in the fifteenth century. HenryOldfield of Nottingham (1580–1620), andRobert Mot of London (1575–1608), mayalso be mentioned under this head.

I have said that seventeenth century bellswere often very richly decorated; and theornamental running borders or elaborate[Pg 112]arabesque patterns which separate thewords of the inscriptions or surroundthe upper and lower edges of the bells,surpass in that respect anything attemptedin mediaeval times (Plate38). ThomasHancox of Walsall (1620–1640) adornedhis bells with reproductions of mediaevalseals; and as late as the beginning of theeighteenth century the Cors of Aldbourne,in Wiltshire, bought up a lot of pieces ofold brass ornaments from which they usedto decorate their bells. At Malmesburyand Tisbury in that county they have leftbells covered with figures of cherubs, coatsof arms and monograms, a medallion ofthe Adoration of the Wise Men, andother curious ornaments. Most of thesefounders, such as John Martin of Worcester,Oldfield of Nottingham, andClibury of Wellington, used trade-markswith their initials, and a bell or otherdevice.

Peal of Eight Bells (Tenor 16 cwt.) for Aberavon Church, Glamorganshire.

This is an example of an ordinary English peal constructed for change-ringing and showssome of the bells “up,” ready for ringing. In this case the frame and stocks are of iron andthe bells are without cannons.

Seventeenth-century Roman lettering,although plain, is often most effective and[Pg 114]artistic; capitals are almost always usedthroughout, and small Roman letters arevery rare. It is not until the middle ofthe next century that it was replaced bythe dull mechanical printing types whichare characteristic of the present day. Butsince the Gothic revival several modernfounders have re-introduced capital lettersof the old style with good effect; notablythe Taylors of Loughborough. Nowadays,however, there is little attempt atornamenting bells; not only the usualinscription-band on the shoulder, but thewhole surface of the bell is utilized forimmortalizing local officials and celebrities.On a bell recently cast for a church on theoutskirts of London are given the names,not only of the Vicar, Bishop, and Archbishop,but of the Prime Minister, Memberof Parliament, and Chairman of the DistrictCouncil!

So far little has been said about theinscriptions placed on bells; but as theseform one of the most interesting features[Pg 115]of the subject, they demand some littleattention.

The earliest inscriptions, those of thefourteenth century, were usually in Latin,and very simple in form. We find merelya name such asIESVS orIOHANNES, or suchphrases asCAMPANA BEATI PAVLI, “thebell of blessed Paul,” orIN HONORE SANCTILAURENCII, “in honour of Saint Lawrence.”More rarely, the founder’s name, as—

MICHAEL DE VVYMBIS MEFECIT

“Michael de Wymbis made me.”