Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- IOPscience - Journal of Physics: Conference Series - Application and Optimization Design of Titanium Alloy in Sports Equipment (PDF)

- Australian Government - Geoscience Australia - Titanium

- Lenntech - Titanium - Ti

- Royal Society of Chemistry - Titanium

- American Journal of Engineering Research - Classification, Properties and Applications of titanium and its alloys used in automotive industry - A Review

- LiveScience - Facts About Titanium

- Chemicool - Titanium Element Facts

- Energy Education - Titanium

- National Center for Biotechnology Information - PubMed Central - Titanium in Dentistry: Historical Development, State of the Art and Future Perspectives

- USGS Publications Warehouse - Titanium (PDF)

- Berkeley Engineering - A new time for titanium

- Chemistry LibreTexts - Chemistry of Titanium

- Nature Communications - Direct production of low-oxygen-concentration titanium from molten titanium

- The Essential Chemical Industry - online - Titanium

titanium

When was titanium discovered?

A compound of titanium and oxygen was discovered in 1791 by the English chemist and mineralogist William Gregor. It was independently rediscovered in 1795 and named by the German chemistMartin Heinrich Klaproth.

What is the atomic number of titanium?

The atomic number of titanium is 22.

How is titanium obtained?

Titanium is obtained by the Kroll process. It cannot be obtained by the common method of reducing the oxide with carbon because a very stable carbide is readily produced, and, moreover, the metal is quite reactive toward oxygen and nitrogen at elevated temperatures.

What are the uses of titanium?

Titanium’s high strength, low density, and excellent corrosion resistance makes it useful in aircraft, spacecraft, ships, and other high-stress applications. It also is used in prosthetic devices, because it does not react with fleshy tissue and bone.

titanium (Ti),chemical element, a silvery graymetal of Group 4 (IVb) of theperiodic table. Titanium is a lightweight, high-strength, low-corrosion structural metal and is used inalloy form for parts in high-speed aircraft. Acompound of titanium andoxygen was discovered (1791) by the English chemist and mineralogistWilliam Gregor and independently rediscovered (1795) and named by the German chemistMartin Heinrich Klaproth.

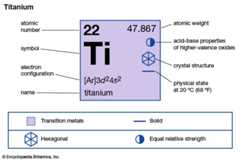

| atomic number | 22 |

|---|---|

| atomic weight | 47.867 |

| melting point | 1,660 °C (3,020 °F) |

| boiling point | 3,287 °C (5,949 °F) |

| density | 4.5 g/cm3 (20 °C) |

| oxidation states | +2, +3, +4 |

| electron configuration | [Ar]3d24s2 |

Occurrence, properties, and uses

Titanium is widely distributed andconstitutes 0.44 percent ofEarth’s crust. The metal is found combined in practically all rocks, sand, clay, and other soils. It is also present in plants and animals, natural waters and deep-sea dredgings, andmeteorites andstars. The two prime commercial minerals areilmenite andrutile. The metal was isolated in pure form (1910) by the metallurgistMatthew A. Hunter by reducing titanium tetrachloride (TiCl4) withsodium in an airtightsteel cylinder.

The preparation of pure titanium is difficult because of its reactivity. Titanium cannot be obtained by the common method of reducing theoxide withcarbon because a very stable carbide is readily produced, and, moreover, the metal is quite reactive toward oxygen andnitrogen at elevated temperatures. Therefore, special processes have beendevised that, after 1950, changed titanium from a laboratory curiosity to an important commercially produced structural metal. In theKroll process, one of the ores, such as ilmenite (FeTiO3) or rutile (TiO2), is treated at red heat with carbon andchlorine to yield titanium tetrachloride, TiCl4, which is fractionally distilled to eliminate impurities such as ferric chloride, FeCl3. The TiCl4 is then reduced with moltenmagnesium at about 800 °C (1,500 °F) in an atmosphere ofargon, and metallic titanium is produced as a spongy mass from which the excess of magnesium and magnesium chloride can be removed by volatilization at about 1,000 °C (1,800 °F). The sponge may then be fused in an atmosphere of argon orhelium in anelectric arc and be cast into ingots. On the laboratory scale, extremely pure titanium can be made by vaporizing the tetraiodide, TiI4, in very pure form anddecomposing it on a hot wire in vacuum. (For treatment of the mining, recovery, and refining of titanium,seetitanium processing. For comparative statistical data on titanium production,seemining.)

Pure titanium is ductile, about half as dense asiron and less than twice as dense as aluminum; it can be polished to a high lustre. The metal has a very low electrical andthermal conductivity and is paramagnetic (weakly attracted to a magnet). Two crystal structures exist: below 883 °C (1,621 °F), hexagonal close-packed (alpha); above 883 °C, body-centred cubic (beta). Natural titanium consists of five stable isotopes: titanium-46 (8.0 percent), titanium-47 (7.3 percent), titanium-48 (73.8 percent), titanium-49 (5.5 percent), and titanium-50 (5.4 percent).

Titanium is important as an alloying agent with most metals and some nonmetals. Some of these alloys have much higher tensile strengths than does titanium itself. Titanium has excellentcorrosion-resistance in manyenvironments because of the formation of a passive oxide surface film. No noticeablecorrosion of the metal occurs despite exposure to seawater for more than three years. Titanium resembles other transition metals such as iron andnickel in being hard and refractory. Its combination of high strength, lowdensity (it is quite light in comparison to other metals of similar mechanical and thermal properties), and excellent corrosion-resistance make it useful for many parts of aircraft,spacecraft, missiles, and ships. It also is used in prosthetic devices, because it does not react with fleshy tissue and bone. Titanium has also beenutilized as a deoxidizer in steel and as an alloying addition in many steels to reduce grain size, instainless steel to reduce carbon content, inaluminum to refine grain size, and incopper to produce hardening.

Although at room temperatures titanium is resistant to tarnishing, at elevated temperatures it reacts with oxygen in the air. This is no detriment to the properties of titanium during forging or fabrication of its alloys; the oxide scale is removed after fabrication. In theliquid state, however, titanium is very reactive and reduces all known refractories.

Titanium is not attacked bymineral acids at room temperature or by hot aqueous alkali; it dissolves in hothydrochloric acid, giving titanium species in the +3oxidation state, and hotnitric acidconverts it into a hydrous oxide that is rather insoluble in acid or base. The best solvents for the metal are hydrofluoric acid or other acids to which fluoride ions have been added; such mediums dissolve titanium and hold it in solution because of the formation of fluoro complexes.