cell

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- British Society for Cell Biology - What is a cell?

- Cell Press - Cell - What is a cell type and how to define it?

- MSD Manual - Consumer Version - Cells

- PNAS - On the evolution of cells

- Chemistry LibreTexts - Cell Tutorial

- Roger Williams University Open Publishing - Introduction to Molecular and Cell Biology - Introduction to Cells

- National Center for Biotechnology Information - The Origin and Evolution of Cells

What is a cell?

A cell is a mass ofcytoplasm that is bound externally by acell membrane. Usually microscopic in size, cells are the smallest structural units of living matter and compose all living things. Most cells have one or morenuclei and otherorganelles that carry out a variety of tasks. Some single cells are complete organisms, such as abacterium oryeast. Others are specialized building blocks ofmulticellular organisms, such asplants andanimals.

What is cell theory?

Cell theory states that the cell is the fundamental structural and functional unit of living matter. In 1839 German physiologist Theodor Schwann and German botanist Matthias Schleiden promulgated that cells are the “elementary particles of organisms” in both plants and animals and recognized that some organisms are unicellular and others multicellular. This theory marked a great conceptual advance in biology and resulted in renewed attention to the processes that take place within cells.

What is the function of the cell membrane?

The cell membrane surrounds every living cell and delimits the cell from the surrounding environment. It serves as a barrier to keep the contents of the cell in and unwanted substances out. It also functions as a gate to both actively and passively move molecules, such as essentialnutrients, into the cell and to remove waste products.

cell, inbiology, the basic membrane-bound unit that contains the fundamentalmolecules oflife and of which all living things are composed. A single cell is often a complete organism in itself, such as abacterium oryeast. Other cellsacquire specialized functions as they mature. These cells cooperate with other specialized cells and become the building blocks of large multicellular organisms, such as humans and otheranimals.

Although cells are much larger thanatoms, they are still very small. The smallest known cells are a group of tiny bacteria calledmycoplasmas; some of these single-celled organisms are spheres as small as 0.2μm in diameter (1μm = about 0.000039 inch), with a total mass of 10−14 gram—equal to that of 8,000,000,000hydrogen atoms. Cells of humans typically have a mass 400,000 times larger than the mass of a single mycoplasma bacterium, but evenhuman cells are only about 20 μm across. It would require a sheet of about 10,000 human cells to cover the head of a pin, and each human organism is composed of more than 30,000,000,000,000 cells.

This article discusses the cell both as an individual unit and as a contributing part of a larger organism. As an individual unit, the cell is capable of metabolizing its ownnutrients,synthesizing many types of molecules, providing its own energy, and replicating itself in order to produce succeeding generations. It can be viewed as an enclosed vessel, within which innumerable chemical reactions take place simultaneously. These reactions are under very precise control so that they contribute to the life and procreation of the cell. In amulticellular organism, cells become specialized to perform different functions through the process ofcell differentiation. In order to do this, each cell keeps in constant communication with its neighbors. As it receives nutrients from and expels wastes into its surroundings, it adheres to and cooperates with other cells. Cooperative assemblies of similar cells form tissues, and a cooperation between tissues in turn formsorgans, which carry out the functions necessary tosustain the life of an organism.

Special emphasis is given in this article toanimal cells, with some discussion of the energy-synthesizing processes and extracellular components peculiar toplants. (For detailed discussion of the biochemistry ofplant cells,seephotosynthesis. For a full treatment of the genetic events in the cell nucleus,seeheredity.)

The nature and function of cells

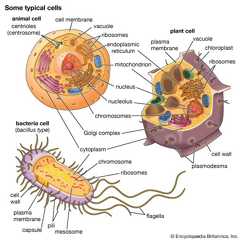

A cell is enclosed by a plasmamembrane, which forms a selective barrier that allows nutrients to enter and waste products to leave. The interior of the cell is organized into many specialized compartments, ororganelles, each surrounded by a separate membrane. One majororganelle, thenucleus, contains the genetic information necessary for cellgrowth andreproduction. Each cell contains only one nucleus, whereas other types of organelles are present in multiple copies in the cellular contents, orcytoplasm. Organelles includemitochondria, which are responsible for the energy transactions necessary for cell survival;lysosomes, which digest unwanted materials within the cell; and theendoplasmic reticulum and theGolgi apparatus, which play important roles in the internal organization of the cell by synthesizing selected molecules and then processing, sorting, and directing them to their proper locations. In addition, plant cells containchloroplasts, which are responsible for photosynthesis, whereby the energy of sunlight is used to convert molecules ofcarbon dioxide (CO2) andwater (H2O) intocarbohydrates. Between all these organelles is the space in the cytoplasm called thecytosol. The cytosol contains an organized framework of fibrous molecules thatconstitute thecytoskeleton, which gives a cell its shape, enables organelles to move within the cell, and provides a mechanism by which the cell itself can move. The cytosol also contains more than 10,000 different kinds of molecules that are involved in cellularbiosynthesis, the process of making large biological molecules from small ones.

Specialized organelles are a characteristic of cells of organisms known aseukaryotes. In contrast, cells of organisms known asprokaryotes do not contain organelles and are generally smaller than eukaryotic cells. However, all cells share strong similarities in biochemical function.

The molecules of cells

Cells contain a special collection of molecules that are enclosed by a membrane. These molecules give cells the ability to grow andreproduce. The overall process of cellular reproduction occurs in two steps: cell growth andcell division. During cell growth, the cell ingests certain molecules from its surroundings by selectively carrying them through itscell membrane. Once inside the cell, these molecules are subjected to the action of highly specialized, large, elaborately folded molecules calledenzymes. Enzymes act ascatalysts by binding to ingested molecules and regulating the rate at which they are chemically altered. These chemical alterations make the molecules more useful to the cell. Unlike the ingested molecules,catalysts are not chemically altered themselves during the reaction, allowing onecatalyst to regulate a specificchemical reaction in many molecules.

Biological catalysts createchains of reactions. In other words, amolecule chemically transformed by one catalyst serves as the starting material, or substrate, of a second catalyst and so on. In this way, catalysts use the small molecules brought into the cell from the outsideenvironment to create increasingly complex reaction products. These products are used for cell growth and thereplication of genetic material. Once the genetic material has been copied and there are sufficient molecules to support cell division, the cell divides to create two daughter cells. Through many such cycles of cell growth and division, each parent cell can give rise to millions of daughter cells, in the processconverting large amounts of inanimate matter into biologically active molecules.