Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

Trajan

Why is Trajan famous?

Trajan was a Roman emperor (98–117 CE) who sought to extend the boundaries of the empire to the east, undertook a vast building program, and enlarged social welfare. He is also remembered forTrajan’s Column, an innovative work of art that commemorated his Dacian Wars.

What was Trajan’s childhood like?

Marcus Ulpius Traianus was born in the Roman province of Baetica (Andalusia). While his family was probably prominent in Baetica, his father was the first to join the imperial service. There is little documentation of Trajan’s early life, but presumably he grew up either in Rome or in various military headquarters with his father.

What were Trajan’s achievements?

Trajan undertook or encouraged extensive public works: roads, bridges, aqueducts, the reclamation of wastelands, and the construction of harbours and buildings. Impressive examples survive in Spain, in North Africa, in the Balkans, and in Italy. In Rome anaqueduct, a public bathing complex, and aforum designed by the architect Apollodorus of Damascus were built.

How did Trajan influence the world?

Trajan abandoned the policy of not extending the Roman frontiers established by Augustus. He added Dacia, Arabia, Armenia, andMesopotamia to the empire, waging war against Decebalus and the Parthians. Upon reaching the Persian Gulf, he is said to have wept because he was too old to repeat Alexander the Great’s achievements in India.

Trajan (born September 15?, 53ce, Italica, Baetica [now in Spain]—died August 8/9, 117, Selinus,Cilicia [now in Turkey]) was aRomanemperor (98–117ce) who sought to extend the boundaries of theempire to the east (notably inDacia,Arabia,Armenia, and Mesopotamia), undertook avast building program, and enlarged social welfare.

Origins and early career

Marcus Ulpius Traianus was born in the Roman province of Baetica (the area roughly equivalent toAndalusia in southernSpain). Although his ancestors, whether or not original settlers, were undoubtedly Roman, or at least Italian, they may well have intermarried with natives. While his family was probably well-to-do and prominent in Baetica, his father was the first to have a career in the imperial service. He became a provincial governor and in 67–68 commander of alegion in thewar the future emperorVespasian was conducting against the Jews. In 70 Vespasian, by then emperor, rewarded him with aconsulship and a few years later enrolled him among thepatricians, Rome’s most aristocratic group within the senatorial class. Finally, he became governor, successively, ofSyria andAsia.

Although there is little documentation of Trajan’s early life, presumably the future emperor grew up either inRome or in variousmilitary headquarters with his father. He served 10 years as a legionary stafftribune. In thiscapacity he was in Syria while his father was governor, probably in 75. He then held the traditional magistracies through thepraetorship, which qualified him for command of a legion in Spain in 89. Ordered to take his troops to theRhine River to aid in quelling a revolt against the emperorDomitian by the governor of Upper Germany (Germania Superior), Trajan probably arrived after the revolt had already been suppressed by the governor of Lower Germany (Germania Inferior). Trajan clearly enjoyed the favour of Domitian, who in 91 allowed him to hold one of the two consulships, which, even under the empire, remained most prestigious offices.

When Domitian had been assassinated by a palaceconspiracy on September 18, 96, the conspirators had put forward as emperor, and the Senate had welcomed, the elderly andinnocuousNerva. His selection represented a reaction against Domitian’s autocracy and a return to the cooperation between emperor and Senate that had characterized the reign of Vespasian. Nevertheless, the imperial guard (thepraetorian cohorts) forced the new emperor to execute the assassins who had secured the throne for him. There was also discontent among the frontier commanders.

Therefore, in October 97, Nerva adopted as his successor Trajan, whom he had made governor of Upper Germany and who seemed acceptable both to the army commanders and to the Senate. On January 1, 98, Trajan entered upon his secondconsulship as Nerva’s colleague. Soon thereafter, on January 27 or 28, Nerva died, and Trajan was accepted as emperor by both the armies and the Senate. Before his accession, Trajan had marriedPompeia Plotina, to whom he remained devoted. As the marriage was childless, he took into his household his cousinHadrian, who became a favourite of Plotina.

Domestic policies as emperor

Trajan deified Nerva and included his name in his imperial title. In 114 he placed before his titleAugustus the adjective Optimus (“Best”). This was undoubtedly intended, by recalling the epithets Optimus Maximus, applied toJupiter, to present Trajan as the god’s representative on earth. Trajan was a much more active ruler than Nerva had been during his short reign. Instead of returning to Rome at once to accept from the Senate the imperial powers, he remained for nearly a year on theRhine andDanube rivers, either to make preparations for a coming campaign intoDacia (modernTransylvania andRomania) or to ensure thatdiscipline was restored and defenses strengthened. He sent orders to Rome for the execution of the praetorians who had forced Nerva to execute the conspirators who had brought him to the throne. He gave the soldiers only half the cash gifts customary on the accession of a new emperor, but in general, he dealt fairly, if strictly, with the armies.

When he returned to Rome in 99, he behaved with respect and affability toward the Senate. He was generous to the populace of Rome, to whom he distributed considerable cash gifts, and increased the number of poor citizens who received free grain from the state. For Italy and the provinces, he remitted the gold that cities had customarily sent to emperors on their accession. He also lessened taxes and was probably responsible for aninnovation for which Nerva is given credit—the institution of public funds (alimenta) for the support of poor children in the Italian cities. Such endowments had previously been established in Italy by private individuals, notably by Trajan’s close friend, the orator and statesmanPliny the Younger, for his native Comum (modernComo) in northern Italy.

For the administration of the provinces, Trajan tried to secure competent and honest officials. He sent out at least two special governors to provinces whose cities had suffered financial difficulties. One wasPliny the Younger, whom he dispatched toBithynia-Pontus, a province on the northern coast ofAsia Minor. The letters exchanged between Pliny and Trajan during the two years of Pliny’s governorship are preserved as the 10th book of his correspondence. Theyconstitute a most important source for Roman provincial administration.

In one exchange, Pliny asked Trajan how he should handle the rapidly spreading sect ofChristians, who, refusing to conform to normal religious practices, suffered from great unpopularity but were, as far as Pliny could see, harmless. In his reply, a model of judiciousness, Trajan advised Pliny not to ferret out Christians nor to accept unsupported charges and to punish only those whose behaviour was ostentatiouslyrecalcitrant. Clearly in Trajan’s time the Roman government did not yet have (and, indeed, was not to have for another century) any policy of persecution of the Christians; official action was based on the need to maintain good order, not on religious hostility. The correspondence also illustrates the wasteful expenditure of cities on lavish buildings and competition for municipal honours, an indication that the finances of the empire were already beginning to show inflationary trends.

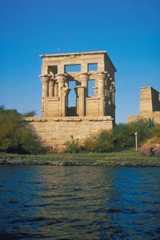

Trajan undertook or encouraged extensivepublic works in the provinces, Italy, and Rome:roads,bridges,aqueducts, the reclamation of wastelands, the construction ofharbours andbuildings. Impressive examples survive inSpain, inNorth Africa, in theBalkans, and inItaly. Rome, in particular, was enriched by Trajan’s projects. A new aqueduct brought water from the north. A splendid public bathing complex was erected on the Esquiline Hill, and a magnificent newforum was designed by the architectApollodorus of Damascus. Itcomprised a porticoed square in the centre of which stood a colossal equestrian statue of the emperor. On either side, the Capitoline and Quirinal hills were cut back for the construction of two hemicycles in brick, which, each rising to several stories, provided streets of shops and warehouses.

- Latin in full:

- Caesar Divi Nervae Filius Nerva Traianus Optimus Augustus

- Also called (97–98 CE):

- Caesar Nerva Traianus Germanicus

- Original name:

- Marcus Ulpius Traianus

- Born:

- September 15?, 53ce, Italica, Baetica [now in Spain]

- Died:

- August 8/9, 117, Selinus,Cilicia [now in Turkey]

- Title / Office:

- emperor (98-117),Roman Empire

- Notable Family Members:

- spousePompeia Plotina

Behind the new forum was a public hall, orbasilica, and behind that a court flanked by libraries for Greek and Latin books and backed by atemple. In that court rose the still-standingTrajan’s Column, an innovative work of art thatcommemorated his Dacian Wars. Its cubical base, decorated with reliefs of heaps of captured arms, later received Trajan’s ashes. The column itself is encircled by a continuous spiral relief, portraying scenes from the two Dacian campaigns. These provide a commentary on the campaigns and also a repertory of Roman and Dacian arms, armour, military buildings, and scenes of fighting. The statue of Trajan on top of the column was removed during theMiddle Ages and replaced in 1588 by the present one ofSt. Peter.