Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser.

1989, Current …

https://doi.org/10.1086/203725…

35 pages

AI

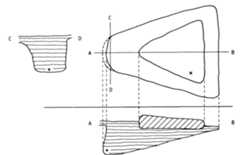

![were “offerings” (cores, flakes, scrapers, a bear humerus] mixed with small rubble, sand, and cinders. Also in- cluded were other bones of bear and deer. It is curious that, in figure 12, IVA is shown filling a depression be- tween the ‘north wall” and the eroded talus alluded to above (i.e., IV—VI). This would indicate that IV had been laid down and eroded before IVA began to accumulate. However, in figures 9 and 10 (sections at right angles to one another), IVA is shown as a typical dome-shaped pile of rubble like VB or VIIA. Also in figure 10, IV is shown as overlying IVA, which would mean that it post-dated that feature. There is no doubt that the stones of IVA collected during a period when either Neandertals were using the cave or their detritus was collecting inside as it fell down the shaft. The clasts that form IVA, with all the rest in this chamber, would have been subjected to downslope movement and would have come to rest at the bottom, where the floor levelled out. This process would have been hastened by the action of rapidly run-](/image.pl?url=https%3a%2f%2ffigures.academia-assets.com%2f6322256%2ffigure_010.jpg&f=jpg&w=240)

Current Anthropology, 2001

Journal of Human Evolution, 2017

The understanding of Neanderthal societies, both with regard to their funerary behaviors and their subsistence activities, is hotly debated. Old excavations and a lack of taphonomic context are often factors that limit our ability to address these questions. To better appreciate the exact nature of what is potentially the oldest burial in Western Europe, Regourdou (Montignac-sur-Vézère, Dordogne), and to better understand the taphonomy of this site excavated more than 50 years ago, we report in this contribution a study of the most abundant animals throughout its stratigraphy: the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus). In addition to questions surrounding the potential bioturbation of the site's stratigraphy, analysis of the Regourdou rabbits could provide new information on Neandertal subsistence behavior. The mortality profile, skeletal-part representation, breakage patterns, surface modification, and comparison with modern reference collections supports the hypothesis that the Regourdou rabbit remains were primarily accumulated due to natural (attritional) mortality. Radiocarbon dates performed directly on the rabbit remains give ages ranging within the second half of Marine Isotope Stage 3, notably younger than the regional Mousterian period. We posit that rabbits dug their burrows within Regourdou's sedimentological filling, likely inhabiting the site after it was filled. The impact of rabbit activity now brings into question both the reliability of the archaeostratigraphy of the site and the paleoenvironmental reconstructions previously proposed for it, and suggests rabbits may have played a role in the distribution of the Neandertal skeletal remains.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

In this paper I focus on the potential of Palaeolithic sites excavated before the establishment of modern methods, aiming to provide reliable information on current debates. Specifically, I will address the reliability of the information coming from such hominin fossil sites to provide data on the first appearance of hominin burials. In three cases (Vogelherd, Balla, and Velika Pećina), hominin fossils previously regarded as Palaeolithic in age, were proven to be much younger after being directly dated. Regardless of the nature of post‐depositional processes which might have affected the integrity and position of the fossils, these cases highlight that sites excavated prior to 1960s–1970s have limited potential in contributing data to the debate on Palaeolithic burials. Subsequently, I present a brief overview of the Middle Palaeolithic sites involved in the debate on the Middle Palaeolithic burials; many of them provide equivocal data on the presence of pits, and very few have hominin fossils directly dated. Therefore, I conclude that the evidence available from earlier excavated sites provides insufficient data to support the existence of Middle Palaeolithic burials.

Arkeoloji'de Ritüel ve Toplum, 2019

The taphonomic processes that cloud reconstruction of past cultural practices and paleodemography are complex and include the preservation of a specimen or the discovery of the site. There has long been a notion of sex related bias in Neandertal burials and it is an easy assumption to make any time the number of specimens attributed to one sex is greater than the other in any interred population. Resampling statistics can be used to test the likelihood that a specific sample is representative of the expected parent population. Here we examine statistical uncertainty in burial contexts using two examples-combined Neandertal burials and commingled remains from a single prehistoric tomb in Peru. The Peruvian tomb represents the problematic ossuary context that many bioarchaeologists encounter, while the Neandertal sample represents one of the most classic discussions of sex bias in our field's history. Using resampling statistics, we fail to reject the null hypothesis that Neandertal burials do not deviate significantly from the expectation of random draws from a population with a balanced sex ratio. The same finding is true for a prehistoric (AD 2000-1000) ossuary burial in highland Peru. The present data do not necessitate inference of male interment bias in Neandertals and suggest caution to bioarchaeologists interpreting commingled remains.

The origins of modern humans: a world …, 1984

published version: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ojoa.12030/abstract/ Childhood is a core stage in development, essential in the acquisition of social, practical and cultural skills. However, this area receives limited attention in archaeological debate, especially in early prehistory. We here consider Neanderthal childhood, exploring the experience of Neanderthal children using biological, cultural and social evidence. We conclude that Neanderthal childhood experience was subtly different from that of their modern human counterparts, orientated around a greater focus on social relationships within their group. Neanderthal children, as reflected in the burial record, may have played a particularly significant role in their society, especially in the domain of symbolic expression. A consideration of childhood informs broader debates surrounding the subtle differences between Neanderthals and modern humans.

Smith, F. & Spencer, F. (eds). The origins of modern humans., 1984

2013

This effort aims to shed light in the Neanderthal behavioral hypothesis. The reader will be exposed to some of the most recent ongoing researches and discoveries that have been trying to improve our knowledge on the extinct species. Considering multiple elements such as; a sophisticated lithic industry, ornamental objects, artistic features and burials, the author aims to give a clear explanation that relies behind the theory of Neanderthal development of cognitive thought. Nevertheless, the reader will be presented with several factors which can alter the researches and the range of error which can emerge from these discoveries, amongst these contact with Anatomically Modern Humans. Overall, the following paper yields important considerations and evaluations on today’s assumptions on the Neanderthal, which could turn out to be more cognitively advanced than generally assumed.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

AI

The study argues that evidence for burial is largely speculative, as contexts imply natural burial rather than purposeful interment, exemplified by La Chapelle-aux-Saints and others.

Sedimentological analyses reveal that many locations presented conditions conducive to natural deposition, complicating interpretations traditionally attributed to ritualistic practices.

The analysis utilized methods from geoarchaeology, sedimentology, and taphonomy to critically evaluate the contexts of purported Neandertal burials, revealing inconsistencies and assumptions.

The findings suggest that inferring ritual behavior from burial practices may be misplaced, indicating that Neandertals likely did not perform mortuary rituals as previously assumed.

The study points to a potential re-evaluation of Neandertal spirituality, arguing that without clear evidence of burial practices, claims of their emotional capacities may need reconsideration.

Journal of Human Evolution, 1999

Current …, 1989

SFU

The question if Neandertal burials are real or fake has always been an issue in Archaeology and in other displaces. Here in this paper I argue that Neandertals were capable of higher thinking to lead to burials of their dead.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2014

The bouffia Bonneval at La Chapelle-aux-Saints is well known for the discovery of the first secure Neandertal burial in the early 20th century. However, the intentionality of the burial remains an issue of some debate. Here, we present the results of a 12-y fieldwork project, along with a taphonomic analysis of the human remains, designed to assess the funerary context of the La Chapelle-aux-Saints Neandertal. We have established the anthropogenic nature of the burial pit and underlined the taphonomic evidence of a rapid burial of the body. These multiple lines of evidence support the hypothesis of an intentional burial. Finally, the discovery of skeletal elements belonging to the original La Chapelle aux Saints 1 individual, two additional young individuals, and a second adult in the bouffia Bonneval highlights a more complex site-formation history than previously proposed.

Comparison of mortuary data from the Middle and Early Upper Paleolithic archaeological record shows that, contrary to previous assessments, there is much evidence for continuity between the two periods. This suggests that if R. H. Gargett’s critique of alleged Middle Paleolithic burials is to be given credence, it should also be applied to the “burials” of the Early Upper Paleolithic. Evidence for continuity reinforces conclusions derived from lithic and faunal analyses and site locations that the Upper Paleolithic as a reified category masks much variation in the archaeological record and is therefore not an appropriate analytical tool. Dividing the Upper Paleolithic into Early and Late phases might be helpful for understanding the cultural and biological processes at work.

Quaternary International, 2014

One the most controversial problems of the Middle Palaeolithic research is the origin of symbolic behavior and who was responsible e only populations of anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens in Africa) or also populations of Neandertals in Western Eurasia? According to the current evidence, there are two opposite concepts. The first one assumes that use of complex stone and bone technology, burying their dead, and making of art objects as well as personal ornaments originated with anatomically modern humans. The second one supports a view that the Neandertals developed their culture in a similar way, convergent or in various contacts with the societies of early Homo sapiens. Their technological equipment enabled them to enter and colonize new areas in northern latitudes, which was impossible without developed knowledge about fire usage, shelter building, and adequate clothing. Neandertals made efficient tools, including composite tools made of various raw materials. In addition, the social relations of Neandertals exemplified an altruistic approach to others. According to the current knowledge, the origin of symbolic behavior cannot be linked only with anatomically modern humans or any isolated Middle Paleolithic population. It appeared much earlier, in the Lower Palaeolithic. It is necessary to remember that archaeological data for remote time are still rare and more evidence is needed to test concepts.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2014

The bouffia Bonneval at La Chapelle-aux-Saints is well known for the discovery of the first secure Neandertal burial in the early 20th century. However, the intentionality of the burial remains an issue of some debate. Here, we present the results of a 12-y fieldwork project, along with a taphonomic analysis of the human remains, designed to assess the funerary context of the La Chapelle-aux-Saints Neandertal. We have established the anthropogenic nature of the burial pit and underlined the taphonomic evidence of a rapid burial of the body. These multiple lines of evidence support the hypothesis of an intentional burial. Finally, the discovery of skeletal elements belonging to the original La Chapelle aux Saints 1 individual, two additional young individuals, and a second adult in the bouffia Bonneval highlights a more complex site-formation history than previously proposed.

Biological Theory, 2017

After we die, our persona may live on in the minds of the people we know well. Two essential elements of this process are mourning and acts of commemoration. These behaviors extend well beyond grief and must be cultivated deliberately by the survivors of the deceased individual. Those who are left behind have many ways of maintaining connections with their deceased, such as burials in places where the living are likely to return and visit. In this way, culturally defined places often serve as metaphors of social association and shared experience. Humans are the only kind of animal that buries their dead, and this gesture is preserved in Paleolithic sites as early as 120,000 years ago. Though not the only method of honoring the dead in human cultures, the emergence of burial traditions in the Middle Paleolithic (Mousterian) implies that both Neanderthals and early Anatomically Modern Humans (AMH) had already begun to conceive of the individual as unique and irreplaceable. Claims of primitive mortuary behavior in earlier periods than the Middle Paleolithic fall short in that they lack any signs of positive social-spatial associations between the deceased and survivors. The archaeological evidence for burial behavior in the Middle Paleolithic provides the first clear translation of mourning into a stereotypical action. These burials therefore may represent the first ritualized bridge between the living and the deceased in human evolutionary history.

In a reply to our paper presenting new evidence supporting an intentional Neanderthal burial at La Chapelle-aux-Saints (Corrèze, France), Dibble et al. (2014) reviewed our data in relation to the original Bouyssonie publications. They conclude that alternative hypotheses can account for the preservation of the human remains within a pit. Here we present new data from our recent excavations and highlight several misinterpretations of the Bouyssonie publications, which, when taken together refute most of their arguments. Moreover, we show that the different hypotheses proposed by Dibble et al. cannot work together and fail to provide a credible explanation for the deposit, reinforcing our demonstration that the burial hypothesis remains the most parsimonious explanation for the preservation of the Neanderthal skeletal material at La Chapelle-aux-Saints.

MPhil Thesis, University of Bergen. 2012.

Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 1992

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2014

The bouffia Bonneval at La Chapelle-aux-Saints is well known for the discovery of the first secure Neandertal burial in the early 20th century. However, the intentionality of the burial remains an issue of some debate. Here, we present the results of a 12-y fieldwork project, along with a taphonomic analysis of the human remains, designed to assess the funerary context of the La Chapelle-aux-Saints Neandertal. We have established the anthropogenic nature of the burial pit and underlined the taphonomic evidence of a rapid burial of the body. These multiple lines of evidence support the hypothesis of an intentional burial. Finally, the discovery of skeletal elements belonging to the original La Chapelle aux Saints 1 individual, two additional young individuals, and a second adult in the bouffia Bonneval highlights a more complex site-formation history than previously proposed.

Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 1996

Summary. Archaeologists often joke that patterning which cannot be explained in socio-economic terms is likely to be of ritual significance. This view has contributed to both reticence about and a rather impressionistic approach to potential ritual patterning in the archaeological record. The application of interpretations derived from the forensic sciences to such contexts may help to exclude natural or taphonomic processes that can mimic these patterns and elucidate aspects of ritual behaviour. In this contribution, we review some recent advances made in the application of such understanding to human remains and provide two examples of another — cadaveric spasm — a condition that has, at times, been interpreted as relating to ‘live’ burial. From these examples, it is clear that the relationship between well-analysed human remains and their context is the key to differentiating natural from ritual processes associated with interment.

International Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 2011

This paper examines the origins of language, as treated within Evolutionary Anthropology, under the light offered by a biolinguistic approach. This perspective is presented first. Next we discuss how genetic, anatomical, and archaeological data, which are traditionally taken as evidence for the presence of language, are circumstantial as such from this perspective. We conclude by discussing ways in which to address these central issues, in an attempt to develop a collaborative approach to them.

Antiquity

Shanidar Cave in Iraqi Kurdistan became an iconic Palaeolithic site following Ralph Solecki's mid twentieth-century discovery of Neanderthal remains. Solecki argued that some of these individuals had died in rockfalls and-controversially-that others were interred with formal burial rites, including one with flowers. Recent excavations have revealed the articulated upper body of an adult Neanderthal located close to the 'flower burial' location-the first articulated Neanderthal discovered in over 25 years. Stratigraphic evidence suggests that the individual was intentionally buried. This new find offers the rare opportunity to investigate Neanderthal mortuary practices utilising modern archaeological techniques.

Scientific reports, 2018

The demise of Neanderthals and their interaction with dispersing anatomically modern human populations remain some of the most contentious issues in palaeoanthropology. The Châtelperronian, now generally recognized as the first genuine Upper Palaeolithic industry in Western Europe and commonly attributed to the Neanderthals, plays a pivotal role in these debates. The Neanderthal authorship of this techno-complex is based on reported associations of Neanderthal skeletal material with Châtelperronian assemblages at only two sites, La Roche-à-Pierrot (Saint-Césaire) and the Grotte du Renne (Arcy-sur-Cure). The reliability of such an association has, however, been the subject of heated controversy. Here we present a detailed taphonomic, spatial and typo-technological reassessment of the level (EJOP sup) containing the Neanderthal skeletal material at Saint-Césaire. Our assessment of a new larger sample of lithic artifacts, combined with a systematic refitting program and spatial project...

Archaeological Human Remains, 2018

The French scholarly landscape of human skeletal studies does not lend itself easily to general overviews due to separation of related disciplines, regionalism, and, most importantly, deep historical origins. Due to separate developmental trajectories, there is no unified discipline of "anthropology" in France, a situation that is similar to the academic organization of other European countries, including Germany and the United Kingdom. When "anthropologists," either biological or sociocultural, interact in joint projects, a development that is encouraged but not formalized, this is considered part of an interdisciplinary approach. This situation is not unique to France, but is likely an outcome of colonization of, especially, parts of Africa, which fostered the development of ethnobiologie as part of ethnology (ethnologie) that includes ethnography, a subject that developed alongside but separately from physical anthropology in the early decades of the twentieth century in France (see Conklin 2013). Paul Broca, a medical specialist in neuroanatomy, is considered the "father of physical anthropology" in France (see below). Thus biological anthropology (also l'anthropologie biologique, bioanthropologie, or anthropobiologie), formerly physical anthropology (l'anthropologie physique), has a longer association with medicine and with paleontology and prehistory (i.e., Paleolithic to Neolithic periods)-stretching well back into the nineteenth century-than with archaeology (i.e., protohistoric and historic periods). In France, prehistory sprang from paleontology (contra Cleuziou et al. 1991, who cite an origin from physical anthropology); philosophy, with its inheritance from the siècle des lumières (the "Enlightenment"); and geology, a science that deals with the "natural history of mankind." With its diverse origins, the interdisciplinary ambition of such studies today is aptly summarized on

Scientific Reports

The origin of funerary practices has important implications for the emergence of so-called modern cognitive capacities and behaviour. We provide new multidisciplinary information on the archaeological context of the La Ferrassie 8 Neandertal skeleton (grand abri of La Ferrassie, Dordogne, France), including geochronological data -14C and OSL-, ZooMS and ancient DNA data, geological and stratigraphic information from the surrounding context, complete taphonomic study of the skeleton and associated remains, spatial information from the 1968–1973 excavations, and new (2014) fieldwork data. Our results show that a pit was dug in a sterile sediment layer and the corpse of a two-year-old child was laid there. A hominin bone from this context, identified through Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry (ZooMS) and associated with Neandertal based on its mitochondrial DNA, yielded a direct 14C age of 41.7–40.8 ka cal BP (95%), younger than the 14C dates of the overlying archaeopaleontological la...

Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews

Mortuary behavior (activities concerning dead conspecifics) is one of many traits that were previously widely considered to have been uniquely human, but on which perspectives have changed markedly in recent years. Theoretical approaches to hominin mortuary activity and its evolution have undergone major revision, and advances in diverse archeological and paleoanthropological methods have brought new ways of identifying behaviors such as intentional burial. Despite these advances, debates concerning the nature of hominin mortuary activity, particularly among the Neanderthals, rely heavily on the rereading of old excavations as new finds are relatively rare, limiting the extent to which such debates can benefit from advances in the field. The recent discovery of in situ articulated Neanderthal remains at Shanidar Cave offers a rare opportunity to take full advantage of these methodological and theoretical developments to understand Neanderthal mortuary activity, making a review of these advances relevant and timely.

Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 2014

Childhood is a core stage in development, essential in the acquisition of social, practical and cultural skills. However, this area receives limited attention in archaeological debate, especially in early prehistory. We here consider Neanderthal childhood, exploring the experience of Neanderthal children using biological, cultural and social evidence. We conclude that Neanderthal childhood experience was subtly different from that of their modern human counterparts, orientated around a greater focus on social relationships within their group. Neanderthal children, as reflected in the burial record, may have played a particularly significant role in their society, especially in the domain of symbolic expression. A consideration of childhood informs broader debates surrounding the subtle differences between Neanderthals and modern humans.

Nature Human Behaviour

This work examines the possible behaviour of Neanderthal groups at the Cueva Des-Cubierta (central Spain) via the analysis of the latter’s archaeological assemblage. Alongside evidence of Mousterian lithic industry, Level 3 of the cave infill was found to contain an assemblage of mammalian bone remains dominated by the crania of large ungulates, some associated with small hearths. The scarcity of post-cranial elements, teeth, mandibles and maxillae, along with evidence of anthropogenic modification of the crania (cut and percussion marks), indicates that the carcasses of the corresponding animals were initially processed outside the cave, and the crania were later brought inside. A second round of processing then took place, possibly related to the removal of the brain. The continued presence of crania throughout Level 3 indicates that this behaviour was recurrent during this level’s formation. This behaviour seems to have no subsistence-related purpose but to be more symbolic in it...

Review of General Psychology, 2006

This article summarizes the literature on the religious mind and connects it to archeological and anthropological data on the evolution of religion. These connections suggest a three stage model in the evolution of religion: One, the earliest form of religion (pre-Upper Paleolithic [UP]) would have been restricted to ecstatic rituals used to facilitate social bonding; two, the transition to UP religion was marked by the emergence of shamanistic healing rituals; and, three, the cave art, elaborate burials, and other artifacts associated with the UP represent the first evidence of ancestor worship and the emergence of theological narratives of the supernatural. The emergence of UP religion was associated with the move from egalitarian to transegalitarian hunter-gatherers.