Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser.

…

26 pages

AI

The paper explores the historical and archaeological evidence surrounding nomad migration in Central Asia, focusing particularly on the relationships between the Asiani, Tochari, and Sacaraucae tribes as well as the Wusun culture. It discusses the discrepancies between western and Chinese sources regarding tribal identities and historical narratives, while emphasizing the importance of archaeological findings in understanding these migrations, particularly in the context of cultural transitions and interactions in Central Asia.

AI

Masters of the Steppe: The Impact of the Scythians and Later Nomad Societies of Eurasia, 2020

This is the concluding essay to the volume of proceedings arising from a conference at the British Museum devoted to Scythians and other Eurasian nomads. It draws together the themes expressed in more detail in individual papers and addresses other questions raised during the course of development of the associated exhibition 'Scythians: warriors of ancient Siberia' and the separate catalogue published to accompany that.

2023

Written sources and archaeological data indicate that the vast territory from the Great Wall of China in the east to the Carpathian Mountains in the west in the first millennium BC was inhabited by the Sak and Sauromat–Sarmatian tribes, who formed a "nomadic culture". Warlike nomads, skilled horsemen, accurate archers and courageous warriors are known in history as "nomadic horsemen tribes". The settlement of nomadic tribes from the steppes of Central Asia to Eastern Europe and Asia Minor in the first half of the first millennium went down in history as the first wave of the "Great Migration" of the peoples from the East to the West. Today this fact is confirmed by written sources and archaeological evidences. As the result of these resettlements, various cultural conflicts have occurred throughout the history of mankind, and nomadic tribes have become recognized by the ancient peoples of Eastern Europe and Asia Minor. The issue of resettlement is the subject of research of foreign and local scientists. However, as it is one of the most important topics that needs to be studied the authors decided conduct scientific research on this topic, study the reasons and ways of migration of the nomadic horsemen tribes to Eastern Europe and Asia Minor, systematize old and new data, conduct a scientific analysis based on the experience of foreign and local researchers. Moreover, scientific conclusions have been done as well as the periods and directions of the conquering campaigns of nomadic horsemen in Asia Minor have been studied.

“My Life is like the Summer Rose”. Maurizio Tosi e l'Archeologia come modo di vivere”.Papers in honour of Maurizio Tosi his 70th birthday / Lamberg-Karlovski C.C., B. Genito, Cerasetti B. (Eds). L.: Bar International Series 2690, 2014 . P. 193-202, 2014

Transition to Modernity, 1992

Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports , 2022

The question of mobility of Bronze Age societies in southern Central Asia is a lively subject for discussion and remains a key aspect for understanding past human life. Central Asia represents a region where mobility and migration had a deep impact on the development of cultural communities. Surrounded by the great empires of the ancient Near East, it exhibited a high ethnic and genetic diversity. In this paper we present a regional study for southern Central Asia of isotopic analyses of 87Sr/86Sr and δ18O of human samples from several Bronze Age sites in southern Turkmenistan (Ulug Depe), south/central Uzbekistan (Dzharkutan, Sapallitepa, Tilla Bulak, Bustan and Bashman 1) and southern Tajikistan (Saridzhar, Gelot and Darnaichi). The three geographical zones manifest different patterns of mobility. The analysis of the Ulug Depe people demonstrates a high rate of immigration during the early periods (EBA) and a tendency for permanent residence. The later periods (MBA) are marked by a decrease in immigration and mobility, indicating a more extensive use of the surrounding landscape. Dzharkutan people displayed a different and complex pattern of mobility and subsistence, with frequent movements during individual lifetime within a limited area. The other sites in the Surkhan Darya Valley and southern Tajikistan indicate active mobility in which individuals migrated within a wide area of southern Central Asia.

Purpose: The region of north-west China is a blank spot for Russian archaeologists. Materials for this part of the PRC have not been published in Russia till now. In this paper the author will try to discuss some aspects of ethnic identity of early nomads. We will see, that connection between archaeological cultures and ethnic names from ancient Chinese chronicles is very complicated. Results: The territory of Gansu and Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region directly borders on Inner Mongolia and on Northern China, that is why it has been drawing the attention of Russian and foreign researchers for a long time. One considers Gansu and Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region as a way of large migrations, other – as a place of mixture of various cultures of the West, the North and the East. During the large-scale archaeological researches which begun in the 80-ies of the last century the considerable material was obtained. Nevertheless, it is already possible to make some significant conclusions relying on this material, particularly to reconsider or add some occurring propositions in Chinese and Russian archaeological literature. In Russian archaeology an issue of comparing archaeological cultures and ethnic groups becomes more and more widely discussed. It is indicative that archaeological culture are based on archaeological sources, and ethnic groups – on written and epigraphic ones. The region of Southern Siberia in Early Iron Age was rather far from ancient civilizations, so connecting famous Pazyryk culture and the yuezhi people is of quite hypothetical character. The point of view, according to which Scythian Siberian world could be identified with di people seems also controvercial. Conclusion: The situation with early nomads who lived to the North of ancient Chinese Kingdoms of «Central plain» in the Spring and Autumn (722–481 B.C.) and Warring States (480–221 B.C.) periods is different. «Records of the Grand Historian» Sima Qian and other chronicle Chinese sources provide us with a number of various ethnonyms, names of tribal unions and proto-states. Those names appear to be random in character, besides reached us in Chinese pronunciation. In this case it would be more correct to speak of exo-ethnonyms. It should be noted that chroniclers’ interest was primarily political, not ethnographical. The whole peoples disappeared from chronicles not because they vanished but because in their recession (due to natural disasters, war conflicts) they did not concern the foreign policy of the Central plain states. For example, the number of reports about the Khitan changed according to their strengthening or weakening. When Hunnu grew weak, the number of reports about them decreased, but when they created their state Xia in the V-th century A. D. it was mentioned immediately as it was important for China. Conventional character of exo-ethnonyms used by chroniclers in the VI-th –II-nd centuries B. C. should be taken into consideration. So two common exo-ethnonyms – rong and di were used by Chinese historians since the Zhou period until at least the Sānguó period (III-d century A. D.).

2019

The nomads of the Eurasian steppes, semi-deserts, and deserts played an important and multifarious role in regional, interregional transit, and long-distance trade across Eurasia. In ancient and medieval times their role far exceeded their number and economic potential. The specialized and non-autarchic character of their economy, provoked that the nomads always experienced a need for external agricultural and handicraft products. Besides, successful nomadic states and polities created demand for the international trade in high value foreign goods, and even provided supplies, especially silk, for this trade. Because of undeveloped social division of labor, however, there were no professional traders in any nomadic society. Thus, specialized foreign traders enjoyed a high prestige amongst them. It is, finally, argued that the real importance of the overland Silk Road, that currently has become a quite popular historical adventure, has been greatly exaggerated.

Вестник Карагандинского университета. Серия «История. Философия. 2024, 29, 4 (116)., 2024

Saryarka in the system of economic and ethnocultural relations of the early nomads of the southern Trans-Urals In the early Saka and Sauromatian-Sarmatian times, the population of the modern Kustanai region, including Turgai, was part of the Trans-Ural horde of the ethnopothesteric association of the early nomads of the Southern Urals. The natural landscape features of the steppes of Central Eurasia determined the boundaries of the association. The Southern Trans-Urals, which include modern Kustanai and Turgai, are the eastern subregions of the vast Ural-Aral cultural and historical region. The nomads of this subregion bordered the nomadic tribes of Saryarka in the east, which is an independent cultural and historical region. The proximity of the populations of two cultural and historical regions contributed to the establishment and maintenance of various kinds of contacts between them. The need for copper and tin in the Trans-Ural steppes determined the economic and ethnocultural ties of the nomads of the Southern Trans-Urals and Saryarka. We can divide these connections into two periods: Early Saka (the VIIIthe first half of the VI century BC) and Sauromato-Sarmatian (the second half of the VImid of the II century BC). The early Saka period had the closest connections, as evidenced by the proximity of material culture objects and the chemical composition of nonferrous metals. In the Sauromatian-Sarmatian period, the intensity of connections sharply decreased due to changes in the ethno-political situation in the steppes of Central Eurasia. The needs of the nomads of the Southern Trans-Urals for copper and products made from it are now satisfied by the products of the Itkul center of metallurgy and metalworking. The supply routes for tin are also evolving, with Central Asian sources joining the previously established Altai sources.

2022

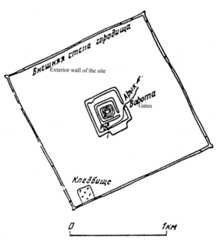

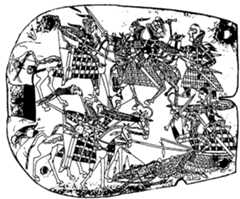

This article is devoted to the study of the material and artistic aspects of nomad migrations from the 2nd century BC to the 2nd century AD. It outlines the basis of artifacts mainly found in archaeological layers of the route followed by the Yuezhi tribe’s movement on the Silk Road. Some of the most striking monuments of this era include the images of warriors in plate armor. These images are mentioned in various archaeological sources. By fixing them in a spatial and temporal dimension, it will be possible to clarify or offer a fractional historical periodization of the era of nomadic migration in Central Asia.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

AI

The paper reveals that the Da Yuezhi migrated westward after a crushing defeat by the Xiongnu in 176 BC, forcing them to cross Da Yuan and the Oxus River.

Archaeological findings, such as rare Kushan coins north of the Oxus, indicate that the Yuezhi established a significant presence in this area substantiating Chinese historical records.

The research indicates that the Wusun culture evolved from local precursors, with significant remains in Semirech'e dated from the second century BC to the first century AD.

The Khalchayan reliefs depict a historical scene where the Yuezhi confront their enemies, presumably the Sakaraules, suggesting this occurred in the second century BC.

The study associates podboy-type burials in southern Tajikistan with the nomadic culture that defeated the Graeco-Bactrian kingdom, demonstrating a continuity in burial practices over time.

Evolutionary Human Sciences, 2020

(The corrigendum is attached as a separate pdf file.) The origin of the Xiongnu and the Rourans, the nomadic groups that dominated the eastern Eurasian steppe in the late first millennium BC/early first millennium AD, is one of the most controversial topics in the early history of Inner Asia. As debatable is the evidence linking these two groups with the steppe nomads of early medieval Europe, i.e. the Huns and the Avars, respectively. In this paper, we address the problems of Xiongnu–Hun and Rouran–Avar connections from an interdisciplinary perspective, complementing current archaeological and historical research with a critical analysis of the available evidence from historical linguistics and population genetics. Both lines of research suggest a mixed origin of the Xiongnu population, consisting of eastern and western Eurasian substrata, and emphasize the lack of unambiguous evidence for a continuity between the Xiongnu and the European Huns. In parallel, both disciplines suggest that at least some of the European Avars were of Eastern Asian ancestry, but neither linguistic nor genetic evidence provides sufficient support for a specific connection between the Avars and the Asian Rourans.

Masters of the Steppe: The Impact of the Scythians and Later Nomad Societies of Eurasia, 2020

How and why major museum exhibitions are put together are rarely explained in detail, let alone in print: this introduction to a volume of studies arising from a joint British Museum and State Hermitage Museum exhibition and conference helps redress that. Here you can read the reasoning behind the 2017/18 exhibition 'Scythians: warriors of ancient Siberia', and see how research and international collaboration underpin these projects. The separate conclusions at the conclusion of the present volume discuss in greater depth approaches to Eurasian pastoral nomadism, compare with evidence from Arabia, and raise much bigger questions over cultural identity and the transfer of ideas and technologies.

Masters of the Steppe, 2020

This book co-edited with Svetlana Pankova presents 45 papers offered for and/or presented at a major international conference held at the British Museum as part of the public programme associated with the 2017 exhibition 'Scythians: warriors of ancient Siberia'. Papers include new archaeological discoveries, results of scientific research and studies of museum collections, most presented in English for the first time. The volume also contains a lengthy introduction explaining how the conference was devised alongside the exhibition and how the exhibition itself was created. The book ends with a long concluding essay exploring the ramifications of the papers and other research into Eurasian nomads, and is followed by a comprehensive subject index. A full list of contributors and their affiliations is also provided. All papers were peer-reviewed. Papers are embargoed for two years but we hope that you can find copies through your institutions and personal Eurasian networks. The title page and main list of contents are attached for reference.

The Light of Discovery: Studies in Honor of Edwin M. Yamauchi, ed. John Wineland, 2007

The focus of this research is preliminary reconstruction of social organization of prehistoric nomads, using categories of mortuary variability. In choosing pastoral nomadism, I consciously target the archaeological research gap, generally reluctant to study archaeological cultures, whose visibility threshold is assumed. The paper introduces the phenomenon of nomadism and issues its studying involves, with a focus on the Scythian-type Eurasian variant. Confining my study to the Scythian Epoch (8-5th c. BC) in the Republic of Tuva, Russia, poses an interesting case for a non-Russian reader as the least known part of the Eurasian nomadic world in the 1st millennium BC. With the prevailing research executed in Russian, I hope to unveil an important niche in the interconnected membrane of Eurasian nomadism. Using the existing theoretical templates of Scythian-type society I testify it against the available archaeological data. The purpose of this paper is therefore to secure a platform for studying nomadic social organization and demonstrating the unforeseen social complexity of this unique phenomenon in social evolution. I will be doing so by looking at the kurgan site hierarchy and the mortuary variability in age, gender and status which show evidence for chiefdom organization with primary processes of early class formation. Key Words: nomadism, Scythian Epoch, mortuary variability, social organisation, Tuva

Nomadic Pathways in Social Evolution, 2003

Current Anthropology, 62 (3), 2021

Nomads, or highly specialized mobile pastoralists, are prominent features in Central Asian archaeology, and they are often depicted in direct conflict with neighboring sedentary peoples. However, new archaeological findings are showing that the people who many scholars have called nomads engaged in a mixed economic system of farming and herding. Additionally, not all of these peoples were as mobile as previously assumed, and current data suggest that a portion of these purported mobile populations remained sedentary for much or all of the year, with localized ecological factors directing economic choices. In this article, we pull together nine complementary lines of evidence from the second through the first millennia BC to illustrate that in eastern Central Asia, a complex economy existed. While many scholars working in Eurasian archaeology now acknowledge how dynamic paleoeconomies were, broader arguments are still tied into assumptions regarding specialized economies. The formation of empires or polities, changes in social orders, greater political hierarchy, craft specialization-notably, advanced metallurgy-mobility and migration, social relations, and exchange have all been central to the often circular arguments made concerning so-called nomads in ancient Central Asia. The new interpretations of mixed and complex economies more effectively situate Central Asia into a broader global study of food production and social complexity.

Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History, 2018

Throughout more than two millennia, the extensive droughty areas in East Asia were occupied by pastoral nomads. A long history exists of hybridity between steppe and agricultural areas. The ancient nomads had a specific pastoral economy, a mobile lifestyle, a unique mentality that assumed unpretentiousness and stamina, cults of war, warrior horsemen, and heroized ancestors that were reflected, in turn, in both their verbal oeuvre (heroic epos) and their arts (animal style). They established vast empires that united many peoples. In the descriptions of settled civilizations, the peoples of the steppe are presented as aggressive barbarians. However, the pastoral nomads developed efficient mechanisms of adaptation to nature and circumjacent states. They had a complex internal structure and created different forms of social complexity—from heterarchical confederations to large nomadic empires. The different forms of identity in pastoral societies (gender, age, profession, rank) are presented in this article. Special attention is given to how ethnic identity is formed from small groups. The ethnic history of the ancient nomads of East Asia is described, particularly for such pastoral societies as the Xiongnu, the Wuhuan, the Xianbei, and the Rouran.

Choice Reviews Online, 2005

Chungará (Arica), 2019

The nomads of the Eurasian steppes, semi-deserts, and deserts played an important and multifarious role in regional, interregional transit, and long-distance trade across Eurasia. In ancient and medieval times their role far exceeded their number and economic potential. The specialized and non-autarchic character of their economy, provoked that the nomads always experienced a need for external agricultural and handicraft products. Besides, successful nomadic states and polities created demand for the international trade in high value foreign goods, and even provided supplies, especially silk, for this trade. Because of undeveloped social division of labor, however, there were no professional traders in any nomadic society. Thus, specialized foreign traders enjoyed a high prestige amongst them. It is, finally, argued that the real importance of the overland Silk Road, that currently has become a quite popular historical adventure, has been greatly exaggerated.