Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser.

…

28 pages

1 file

In an article published in 2008 in Paléorient, a series of arguments have been listed which would allow dating the last phase Résumé : Dans un article publié en 2008 dans Paléorient, une série d'arguments a été présentée pour dater la phase fi nale de la période III et la période IV de Shahr-i Sokhta au cours de la seconde moitié du III e millénaire et au tout début du II e millénaire av. J.-C. Une telle datation pourrait impliquer de possibles interactions entre les sites du système de l'Helmand (Shahr-i Sokhta et Mundigak) et la civilisation de l'Indus. Cet article nous conduit tout d'abord à un examen d'ensemble des questions chronologiques à l'échelle des régions indo-iraniennes. Nous passons ensuite en revue les éléments utilisés par les auteurs de l'article précédent pour soutenir une contemporanéité entre les sites de l'Helmand aux périodes III et IV de Shahr-i Sokhta et la civilisation de l'Indus. Puis, en nous fondant notamment sur la séquence des sites de la bordure occidentale de la vallée de l'Indus et du Makran, nous examinons le bienfondé de ces rapprochements proposés entre Shahr-i Sokhta et les sites de la civilisation de l'Indus. Sample Region Site / period 14C Age BP 68 % (1σ) cal BC ranges 95.4 % (2σ) cal BC ranges Beta 18843*

AI

Recent excavations by S.M.S. Sajjadi revealed tombs at Shahr-i Sokhta dating to Period IV, providing clearer chronological links with Mehrgarh and Nausharo, suggesting continuity in cultural trends.

The study indicates that Shahr-i Sokhta may be contemporaneous with key Helmand sites, with evidence linking its pottery styles and cultural artifacts to the Helmand River hydrographic system.

The introduction of bichrome and polychrome pottery in the region indicates complex exchange networks, particularly in the tradition of decoration techniques emerging around the mid-4th millennium BC.

The research employed calibrated radiocarbon dating and stratigraphic comparisons across various key archaeological sites to critically evaluate periods of occupation and cultural exchange.

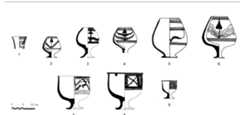

Vessels displayed stylistic links to both local and regional traditions, revealing a dynamic exchange of artistic concepts and techniques across the Indo-Iranian region during the 3rd millennium BC.

Paléorient, 34.2, 5-35, 2008

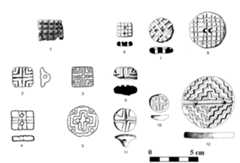

This paper presents a systematic review of the archaeological evidence for cultural interaction between the Helmand and the Indus during the 3rd millennium BCE. A series of artefacts found at Shahr-i Sokhta and nearby sites (Iranian Seistan) that were presumably imported from Baluchistan and the Indus domain are discussed, together with fi nds from the French excavations at Mundigak (Kandahar, Afghanistan) that might have the same origin. Other artefacts and the involved technologies bear witness to the local adaptation of south-eastern manufactures and practices in the protohistoric Sistan culture. While the objects datable to the fi rst centuries of the 3rd millennium BCE fall in the so called "domestic universe" and refl ect common household activities, in the centuries that follow we see a shift to the sharing of luxury objects and activities concerning the display of a superior social status; but this might be fruit of a general transformation of the archaeological record of Shahr-i Sokhta and its formation processes.

Nuclear Inst. and Methods in Physics Research B, 2019

In 2016 CIRCE and the ISMEO Italian Archaeological Mission in Pakistan launched a specific project specifically aimed at investigating a cultural phase that had not been previously explored, namely the transition phase between Late Bronze/Early Iron age (1200–800 BCE) and Early-Historic phases (c. BCE 500–80 AD) in the ancient Gandhara region. Current excavations of the key-site of Barikot (Bir-kot-ghwandai), supported by a substantial series of new radiocarbon dates, provide a new, very detailed chronological-cultural framework for the social evolution of ancient Swat after the late Bronze age. Thanks to the radiocarbon data published in this work, for the first time at Barikot it has been possible to discover or better define the Achaemenian, Graeco- Bactrian and Indo-Greek acculturational phases. Barikot is identified with the city of Bazira/Beira mentioned by Alexander’s historians’ and the siege of Alexander the Great, in 327 BCE, falling exactly in one of the identified archaeological frames.

RADIOCARBON, Vol 49, Nr 2, 2007

Sohr Damb/Nal, the type site of the Nal complex, is located in Balochistan, Pakistan. After 1 season of excavation by H Hargreaves in 1924, which made the polychrome Nal pottery widely known, no further work took place until the Joint German-Pakistani Archaeological Mission to Kalat resumed excavations in 2001. So far, 4 seasons of excavations have been undertaken, which have revealed 4 periods of occupation, dated from about 3800 to 2000 BC. The well-stratified assemblages provide new insights into cultural processes and developments, and enhance the comparative frameworks through typological series and a comprehensive set of radiocarbon dates. This information is essential for assessing cross-cultural relations and the date of urbanization. In this paper, the 14C dates from Sohr Damb/Nal are presented and their cultural context is discussed. Period III has several links to sites in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Iran, such as Miri Qalat IIIb–c, Mehrgarh VI–VII/ Nausharo I, Quetta III, Mundigak IV, and Shahr-e Sokhta II–III. Period IV represents a Kulli-Harappan occupation, which is dated to the second half of the 3rd millennium BC.

Paléorient, 2008

ABSTRACT

Exchange and interaction between early state-level societies in Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley during the 3rd millennium BC has been documented for some time. The study of this interaction has been dominated by the analysis of artifacts such as carnelian beads and marine shell, along with limited textual evidence. With the aid of strontium, carbon, and oxygen isotopes, it is now possible to develop more direct means for determining the presence of non-local people in both regions. This preliminary study of tooth enamel from individuals buried at Harappa and at the Royal Cemetery of Ur, indicates that it should be feasible to identify Harappans in Mesopotamia. It is also possible to examine the mobility of individuals from communities within the greater Indus Valley region.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

Excavation and Researches at Shahr i Sokhta 3, E. Ascalone and S.M.S Sajjadi(eds), Pishin Pajouh, Tehran, Iran. pp. 233-266, 2022

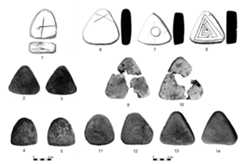

The cultural basin around Shahr-i Sokhta stretches from the Ramshar area north of the site to the Tasuki region known as the Rud-i Biaban area in the south, forming a strip of land approximately 45 km long. The present article is the result of a nonprobabilistic survey carried out in April 2019 which covers the east and southeast of Shahr-i Sokhta from Ramshar to Rud-i Biaban. During the surface survey, a total of 32 sites were visited and surface finds including pottery sherds and stone objects such as alabaster vessel fragments and micro blades were collected EXCAVATIONS AND RESEARCHES AT SHAHR-I SOKHTA 3 234 and registered. The surveyed sites of the area have various chronologies, from 3000 BC to 2000 BC and later. To better understand the distribution of these sites, a general classification based on the comparative dating of the collected pottery was performed, assigning the sites to three main periods: a) the early third millennium BC; b) Periods III-II of Shahr-i Sokhta and c) Period IV of Shahr-i Sokhta and the Rud-i Biaban phase.

Decades in Deserts: Essays on Near Eastern Archaeology in honour of Sumio Fujii, 2019

PREHİSTORYA’NIN “ABİ”Sİ HARUN TAŞKIRAN’A ARMAĞAN KİTABI / STUDIES IN HONOUR OF HARUN TAŞKIRAN, 2023

Archaeological surveys carried out in Sindh in the 1970s were resumed during the last decade and are still underway. They have shown that Upper Palaeolithic assemblages occur in few territories of the Greater Indus Valley, Lower Sindh in particular. Among them are the northern coast of the Arabian Sea and the banks of the seasonal watercourses that flow into the Indian Ocean from the desert regions of the interior. The chronology of the Upper Palaeolithic complexes is difficult to define because the sites consist of surface knapped chert artefacts, in association with which organic material suitable for dating has never been retrieved. The prehistoric lithic assemblages recovered from the southernmost territories of Lower Sindh consist of typical instruments, among which are thick, curved, unilateral abrupt-retouched points obtained from core rejuvenation bladelike flakes. The blanks have been detached from corticated bipolar cores obtained from small chert pebbles. Upper Palaeolithic workshops for the production of bladelet blanks are very common in the Rohri, Ongar and Daphro Hills near Sukkur and Kotri respectively.

Geology, 2012

Quaternary Research, 2019

This article presents a geomorphological and micromorphological study of the locational context of four Indus civilisation archaeological sites-Alamgirpur, Masudpur I and VII, and Burj-all situated on the Sutlej-Yamuna interfluve in northwest India. The analysis indicates a strong correlation between settlement foundation and particular landscape positions on an extensive alluvial floodplain. Each of the analysed sites was located on sandy levees and/or riverbank deposits associated with former channels. These landscape positions would have situated settlements above the level of seasonal floodwater resulting from the Indian summer monsoon. In addition, the sandy soils on the margins of these elevated landscape positions would have been seasonally replenished with water, silt, clay, and fine organic matter, considerably enhancing their capacity for water retention and fertility and making them particularly suitable for agriculture. These former landscapes are obscured by recent modification and extensive agricultural practices. These geoarchaeological evaluations indicate that there is a hidden landscape context for each Indus settlement. This specific type of interaction between humans and their local context is an important aspect of Indus cultural adaptations to diverse, variable, and changing environments.

Ancient Iran and Its neighbours : local developments and long-range interactions in the 4th millennium BC, 2013

Rescue excavations carried out from 2006 to 2009 at the site of the plundered graveyard of Mahtoutabad (near Konar Sandal South), revealed the remains of three successive settlements dating to the fourth millennium BC. The earliest phase of occupation, Mahtoutabad I, lies above the virgin soil, at a depth of about 3.5–4 m below the present surface and was radiocarbon dated to the late fifth–early fourth millennium BC. The second phase, Mahtoutabad II, above the remains of the first settlement, is represented by a thick series of sediments that are attributed, on archaeological considerations, to the last centuries of the first half of the fourth millennium BC. The occupation labelled Mahtoutabad III, limited to secondary deposits in a restricted area of the site, is distinguished by ceramics that are linked, on stylistic-morphological grounds, to the Middle and Late Uruk-related pottery assemblages of the central-eastern Iranian Plateau. Mahtoutabad IV, finally, is the large cemetery of the third millennium BC. This paper briefly describes the stratigraphy of the site, identifying some crucial information on the third-millennium graveyard. It then focuses on the archaeological record of the earliest phase, Mahtoutabad I, and discusses its cultural links with contemporary ceramic assemblages in the same general geographic area.

Journal of Archaeological Science, 2004

The site of Harappa in central Pakistan has been the primary source of information on Indus Valley cultural and natural landscapes in the Upper Indus Basin. While the site has been excavated for over 100 years, little was known of the pre-occupation history and environments responsible for the culture's emergence in the third millennium BC. Recent geoarcheological investigations of sites sharing the same landform as Harappa-the Bari Doab-along the ancient Beas River have synthesized sediment, soil, and cultural stratigraphies that place Harappa in the context of a regional landscape history. Two key sites-Lahoma Lal Tibba and Chak Purbane Syal-illustrate that larger floodplains of the Indus system stabilized sometime in the early Holocene, when soil development exceeded rates of alluviation. The site of Harappa was revisited to procure radiocarbon dates beneath initial occupation horizons. The stratigraphy and dates established the Pleistocene/Holocene interface and confirmed coeval trends of diminished Early Holocene floodplain accretion and sustained soil formation. Pedogenesis continued at least to the beginning of the fifth millennium BP when occupation began to intensify along the Beas and elsewhere in the Upper Indus. Site formation sequences at Lahoma Lal Tibba and Chak Purbane Syal mirror those of Harappa proper, albeit on a smaller scale.