Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser.

…

28 pages

1 file

AI

The paper explores the impact of the Mediterranean-wide crisis in the 12th century BCE on the Paphos region of Cyprus, highlighting that despite the broader disintegration of land-based empires, Paphos experienced economic and political flourishing. It discusses the establishment of new settlements like Maa-Palaeokastro and the transformation of material culture, particularly through the introduction of wheel-made pottery inspired by Aegean models. Utilizing a holistic approach, the study examines migration phenomena and the unique regional responses to the crisis.

AI

![Fig. 6 Ivory mirror handle from Evreti Tomb KTE VII] (Courtesy of the Department of Antiquities, Cyprus)](/image.pl?url=https%3a%2f%2ffigures.academia-assets.com%2f58605391%2ffigure_007.jpg&f=jpg&w=240)

![Fig. 12 ‘White Painted Wheelmade III’ hemispherical bow] with round impression below base from Evreti (outside view on the left, inside view on the right) (No. TE II: 474. Photo by the author. Courtesy of C. von Rtiden and the Department of Antiquities, Cyprus)](/image.pl?url=https%3a%2f%2ffigures.academia-assets.com%2f58605391%2ffigure_013.jpg&f=jpg&w=240)

Centre d'Etudes Cypriotes 43 (2013)

A LONGER ANTIQUITY? Cyprus, Insularity and the Economic Transition Salvatore COSENTINO Résumé. Depuis les années 1980 un certain nombre d'études ont été consacrées à l'archéologie et à l'histoire des grandes îles méditerranéennes dans l'Antiquité tardive et au début du Moyen Âge. L'impression générale qui s'en dégage est que la période qui va du iv e au vii e s. apr. J.-C. constitue globalement une époque de vraie prospérité, aussi bien pour les grandes que les petites îles. Parmi les arguments qui sont en faveur de cette appréciation économique favorable, cet article insiste sur le faible impact de la militarisation sur les paysages, l'aménagement territorial et les sociétés insulaires. Il tente également de définir jusqu'à quel point l'histoire socio-économique de Chypre dans l'Antiquité s'accorde avec celle d'autres grandes îles de Méditerranée, comme la Sardaigne, la Crète et la Sicile.

This article explores the relationship between power and cult, not in the age of the Cypriot city-kingdoms per se but rather in the context of a changing political landscape that eventually led to the abolition of the autonomous polities and the establishment of a new order by the Ptolemaic Empire. In particular, this contribution explores some of the Cypro-Classical kings' internal responses to the changing political map of the Mediterranean, suggesting a shift from eastern to western orientations and cultural and iconographic prototypes. Furthermore, it attempts to put Cyprus in a broader context of Hellenistic monarchies in the Mediterranean, considering the resulting transformations of the island's political geography and cultural identities. Finally, through the medium of sacred landscapes, this article explores the response of Cypriot populations (elite and non-elite) to Ptolemaic power and rule.

2022

1. Abstract ………….…..……………………………………..............…………...........…. 1 2. The breakdown of the Late Bronze Age economy: Political Empires in Distress ………………………………………………………………….................................. 2 3. Cyprus during the « Crisis Years » ………………...........……………………. 3 4. The settlement histories Cyprus ...during the « Crisis Years » ….5 4.1 The case of Enkomi ……………………………………........................………... 5 4.2 Settlements with destruction-less continuity ……………………......…. 6 4.3 Destruction-less abandonments ……………………………….............……. 6 4.4 Florishing amidst a crisis ………………………………………..................….. 7 1.1 New foundations …………………………………………….......................……... 7 5. Conclusions …………………………….……........................………………………. 9

Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 372 (2014) 240-242, 2014

The strategic location of Cyprus in the north-eastern corner of the Mediterranean Sea has always played a significant role in its history. At the crossroads between East and West, and facing the fertile valley of the Nile, the island in antiquity was in close proximity to the great civilizations of the Syro-Palestinian coast, while it was also linked to areas of the Aegean and Asia, through intense interactions and exchanges. As a consequence, Cyprus attracted the attention of several great Empires of the antiquity such as the Assyrians, the Persians, the Macedonians and the Romans. The control of the island -the third largest island in the Mediterranean basin after Sicily and Sardinia -was of a crucial importance for the political, economic and strategic interests of these major Empires. Cyprus was exalted for its important geographical position, but mainly for its legendary wealth, already in antiquity. The Greek geographer Strabo (63BC -AD21) wrote in 23 BC: « In fertility Cyprus is not inferior to any one of the islands, for it produces both good wine and good oil, and also a sufficient supply of grain for its own use. And at Tamassus there are abundant mines of copper, in which is found chalcanthite and also the rust of copper, which latter is useful for its medicinal properties. Eratosthenes says that in ancient times the plains were thickly overgrown with forests, and therefore were covered with woods and not cultivated; that the mines helped a little against this, since the people would cut down the trees to burn the copper and the silver, and that the building of the fleets further helped, since the sea was now being navigated safely, that is, with naval forces, but that, because they could not thus prevail over the growth of the timber, they permitted anyone who wished, or was able, to cut out the timber and to keep the land thus cleared as his own property and exempt from taxes ». Rich, fertile meadows, abundant fresh water, dense forests that covered the mountains of Troodos and the Kyrenia mountain range, olives, vines, fruit and nuts, figs, almonds and pistachios, carobs, pomegranates, palms and lotus, wild animals like moufflon, wild pig, fox, also domesticated animals like, pigs, goats, sheep, dogs and cats composed the Cypriot environment of the ancient times. The ancient Cypriot environment was composed by rich, fertile meadows, abundant fresh water, and dense forests that covered the mountains of Troodos and the Kyrenia mountain range. The flora of the island was rich with products, such as olives, vines, fruit, figs, almonds and pistachios, carobs, pomegranates, palms and lotus. The fauna consisted of wild animals, such as the moufflon, wild pig, and the fox, while domesticated animals included pigs goats, sheep, and cats. Ancient Cyprus was particularly famous for its copper resources. Due to the discovery and mining of copper ores the island became infamous for the production and trading of raw material and metal objects. The principal copper ores are on the north and northeast slopes of the Troodos mountains. P a n o s C h r i s t o d o u l o u O p e n U n i v e r s i t y o f C y p r u s Prehistoric Cyprus Aims This section succinctly describes the characteristics of the period of Cypriot history known as the prehistoric period, all of which are based almost exclusively on archeological findings. The most widely accepted and valid theories concerning the islanders' way of life from 8000 to 750 BC are presented. There follows an examination of the changes which occurred in cultural, economic, political, and social areas, and especially the ones which led to the foundation of the Cypriot kingdoms, the main constitutional form encountered in Cyprus during the archaic and classical years. After reading the first section the student should: -Establish the chronological outlines of the following periods of prehistoric Cyprus: -Neolithic age. -Chalcolithic age. -Bronze age. -Describe the characteristics of each of the aforenamed periods. -Recognise and comprehend the changes which led to the foundation of the Cypriot Kingdoms. P a n o s C h r i s t o d o u l o u O p e n U n i v e r s i t y o f C y p r u s Neolithic Age The first evidence of organised human life in Cyprus dates to 8000 B.C, which marks the beginning of the Neolithic period. The most renowned Neolithic settlement on the island, and one of the most important sites in the Mediterranean, is that of Khirokitia. Built on a hill near a river on the south end of the island, the settlement overlooks a wider area. Its location offered natural protection to its inhabitants while the fertile plain stretching south of the hill must have contributed to the further development of the settlement itself. Archaeological evidence points to the existence of a culturally and economically developed society. The origin of the Neolithic culture on the island is uncertain, although one hypothesis stresses the arrival of people from the opposite Syro-Palestinian coastland or from A. Minor, based on similarities in the archaeological assemblages. Another hypothesis underlines the importance of endogenous factors in the development of the Neolithic culture. People lived in small circular buildings -the so-called tholoi -and buried their dead directly beneath their houses. Some of the burial customs, such as the position of the dead and the stone placed on the scull, bear similarities to customs encountered in other eastern areas. From the tools found at the site we can conclude that the inhabitants were familiar with agriculture and that they had tamed the sheep and the pig. Other evidence suggests that the inhabitants of Khirokitia were also hunters and knew how to work stone and other materials. The Neolithic period is distinguished into two phases, the Aceramic and the Ceramic phase, both of which are attested in Khirokitia. As the name of the first phase suggests, it is characterised by the existence of stone vessels, while the Ceramic phase is distinguished by the use of clay and firing for the manufacture of ceramic vessels. The site of Khirokitia, therefore, represents an important technological development that occurred in the Neolithic period, associated with changes in food production and storage. Abundant vessels, tools, figurines and ornaments have been recovered from both phases, elucidating aspects of economy and ideology in the Neolithic culture. It seems possible that the settlement of Khirokitia had gone into decline by 5500 BC. Other important sites of the Neolithic period in Cyprus are Kalavassos-Tenta (Aceramic phase) and Sotira. The Chalcolithic period is a period of important changes in the lives of the island's inhabitants. Ceramic findings indicate the existence of new cultural developments and the tendency to experiment, through the creation of new ceramic forms and the use of geometric motives and red tincture. The Red on White Ware is probably the most famous example of the pottery styles prevalent during this period. Artistic works of sculpture indicate the skills and sense of taste of the manufacturers. In particular, the abundance of cruciform figurines has led to the development of the idea concerning the worship of the goddess of fertility. An important settlement dating to this period is that of Erimi, on the south of Cyprus, which is comprised of large round habitations. Its inhabitants must have The Neolithic settlement of Choirokoitia P a n o s C h r i s t o d o u l o u O p e n U n i v e r s i t y o f C y p r u s enjoyed relatively high living standards, whereas at the same time there are indications of the first Cruciform figurine found in the village of Pomos (Cyprus Archaeological Museum) use of the metal which is to mark the economy -amongst other things -of the island for more than three thousand years. Copper is used to make the first copper tools, though more systematic use of the metal is not made until later, in the Late Bronze Age. The process of copper moulding was also still unknown during this period. Agriculture and cattle breeding are now sustained on a regular and intensive basis, while the great variety characterising the tools of this period manifests the imminent economic change. Major sites during the Chalcolithic period can be found at Lemba, Kissonerga and Souskiou. Many aspects of this period, however, are unknown, due to the limited archaeological record.

American Journal of Archaeology 112: 659-684. , 2008

Ancient cultural encounters in the Mediterranean were conditioned by everything from barter and exchange through migration and military engagement to colonization and conquest. Within the Mediterranean, island relations with overseas polities were also affected by factors such as insularity and connectivity. In this study, we reconsider earlier interpretations of cultural and social interactions on Cyprus at the end of the Late Bronze Age and beginning of the Iron Age, between ca. 1200 and 1000 B.C.E. Examining a wide range of material evidence (pottery, metalwork, ivory, architecture, coroplastic art), we revisit notions (the “colonization narrative”) of a major migration of Aegean peoples to Cyprus during that time. We argue that the material culture of 12th–11th-century B.C.E. Cyprus reflects an amalgamation of Cypriot, Aegean, and even Levantine trends and, along with new mortuary traditions, may be seen as representative of a new elite identity emerging on Cyprus at this time. Neither colonists nor conquerors, these newcomers to Cyprus—alongside indigenous Cypriots—established new social identities as a result of cultural encounters and mixings here defined as aspects of hybridization.

Responses to the 12th Century BC Collapse Edited by Mait Kõiv and Raz Kletter www.zaphon.de Responses to the 12th Century BC Collapse MWM 10 Melammu Workshops and Monographs 10 Recovery and Restructuration in the Early Iron Age Near East and Mediterranean, 2024

Responses to the 12th Century BC Collapse Recovery and Restructuration in the Early Iron Age Near East and Mediterranean. Proceedings of the 9th Melammu Workshop, Tartu Edited by Mait Kõiv and Raz Kletter Responses to the 12th Century BC Collapse Melammu Workshops and Monographs 10

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

Le pouvoir et la parole. Mélange en mémoire de Pierre CARLIER. Sous la direction de A. Guieu-Coppolani, M-J Werlings et J. Zurbach Etudes Anciennes 76 De Boccard – Paris, 2021

In 1788, the year before the outbreak of the French Revolution, the printing house of Michael Glykys in Venice published a Greek treatise, which was later deservedly described by Konstantine Sathas in the Mediaeval Library (volume II, Venice 1873) as the only scholarly monograph of Modern Greek literature since the fall of Constantinople 1. It was entitled A Chronological History of the island of Cyprus and had been written by a Greek cleric, Archimandrite Kyprianos, who had benefitted from studies in the University of Padua. Founded in 1222, the official academic institution of the Venetian Republic had remained unaffected by the Inquisition and had become a center of the European Enlightenment 2. Kyprianos Kouriokourineos belonged to the downtrodden society of an enslaved Greek people (Cypriots had been living under Ottoman rule since 1571); this offspring of a rural family offered his fellow men the first history of "their famous native island 3 ". I underline first since this is the first socio-political history of Cyprus that was written in the language of its people, by one of its people, and was specifically addressed to its people. Being an autochthon Kyprianos could relate to the Cypriot habitus 4 , to the intangible, collective identity of the island. * In 2003 in Edinburgh in the course of the symposium on Ancient Greece: from the Mycenaean palaces to the Age of Homer (DEGER-JALKOTZY S. and LEMOS I. [ed.], Edinburgh, 2006), I had the honour of making the acquaintance of the author of La Royauté en Grèce avant Alexandre; he had, on that day, delivered an epical paper on "Wanax and Basileus in the Homeric poems". Pierre did not treat history and archaeology as two distinct subjects. May this paper stand in salutation of his exemplary approach to both.

LES ROYAUMES DE CHYPRE À L’ÉPREUVE DE L’HISTOIRE Transitions et ruptures de la fin de l’âge du Bronze au début de l’époque hellénistique sous la direction de Anna Cannavò et Ludovic Thély, 2018

Abstract In the last two decades the study of Iron Age Cyprus has made a gradual but decisive move away from externally-generated cycles of complexity and ethnic (“Hellenization” and equally “Phoenicianization”) narratives. Colonization constructs have begun to fade giving way to a “Cyprocentric” research methodology which considers the development of the island’s micro-states as a longue durée episode distinguished by settlement and landscape continuities, transformations and transition, rather than sharp breaks that separate the Late Bronze from the Iron Age. This paper shows that the history of the island’s ancient States consists of the fluid regional histories of many polities: some of them remain archaeologically invisible and mysterious to this day ; a few others appear historically less elusive because they achieved a degree of longevity as Iron Age “kingdoms” to the end of the fourth century BC.

In “Up to the Gates of Ekron” (1 Samuel 17:52), Essays on the Archaeology and History of the Eastern Mediterranean in Honor of Seymour Gitin. S. White Crawford, A. Ben-Tor, J.P. Dessel, W.G. Dever, A. Mazar, and J. Aviram (eds). Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society: 461-475.

19th International Congress of Classical Archaeology. Panel 8.13: Central places and un-central landscapes: political economies and natural resources in the longue durée (Cologne/Bonn, Germany), 2018

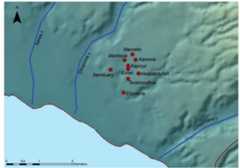

EXTENDED ABSTRACT From the Hinterland to the Coastal Landscape: the political economy of a Cypriot central place (extended abstract) That Ancient Paphos functioned as a place of economic and ideological centrality in the context of a Cypriot polity, from circa the 13 th c. BC to the very end of the fourth c. BC., is amply confirmed by a wealth of architectural and mortuary evidence, which in the first millennium BC are amplified by scores of inscriptions and silver coins issued by state-leaders, invariably identified as kings of Paphos 1. The richness of the epigraphical and material evidence notwithstanding, the key question regarding the economic system(s) that led to the millennium-long success of Ancient Paphos as a central place, had not been approached before the initiation of the Palaepaphos Urban Landscape Project (PULP), a landscape analysis programme that has been running since 2006 2. PULP's diachronic approach to the little known landscape of the region of Paphos has revealed in the interplay of natural (e.g. coastal uplift and river silting) and anthropogenic (e.g. Mediaeval sugar cane plantations) factors, the reasons behind the drastic transformations of the micro-region's economy from prehistory to the present day 3. With respect to antiquity, we are now in a position to provide a preliminary, though still sketchy, cultural biography 4 of the region and a more robust and secure one of the central place. When did the region of Paphos first come under a central authority, which maintained communication and exchange routes from the high altitude of the Paphos forest-where the rich timber and metal resources are concentrated-all the way south to the coast (MAP)? Contrary to the evidence from the north coast of Cyprus, where incipient stages in the emergence of socio-political complexity, including offshore exchanges, are in evidence since the Early Bronze Age 5 , the configuration of the human territory of Paphos in the later third millennium BC shows no internal networking and no signs of contact with the coast. The currently

this paper attempts to show that the interpretation of the complex cultural and political configurations of iron Age cyprus rests on a 1,000-year long macrohistoric overview that focuses on continua rather than breaks. it maintains that the first-millennium B.c.e. kingdoms operated on very much the same decentralized politicoeconomic system as late cypriot polities in the 13th and 12th centuries. it argues that the long-term dynamics of this late cypriot model were actively and successfully promoted in the Archaic and classical periods by preponderantly Greek central authorities. it is mostly Greek-named basileis (kings) that are found closely associated with the fundamental continua-the cypriot script, the regional settlement hierarchy pattern, cult practice, and an economy based on trading metals-to the end of the fourth century B.c.e. this article argues that Greek-speaking people had become a constituent part of the sociopolitical structure of the island by the last centuries of the second millennium as a result of a migration episode.* Ptolemaic/Hellenistic 310-30 B.c.e. roman 30 B.c.e.-330 c.e. culturAl AND PoliticAl coNFiGurAtioNS iN iroN AGe cYPruS 2008]

Cahiers du Centre d'Etudes Chypriotes, 2023

The transition from the 12th to the 11th century BC in Cyprus constitutes a critical junction that marks the close of the Late Bronze Age and the inception of the Early Iron Age. This transformative phase remains poorly known and ill defined, not least because of the remarkable dearth of stratified settlement strata exposed to this day on the island. Recent investigations by the French Archaeological Mission at Kition, within the locality of Bamboula, situated on the northern part of the modern-day town of Larnaca, have brought to light a continuous stratigraphic succession of floor layers spanning from the 13th to the 11th centuries BC, thus marking an exceptional instance on an island-wide basis. The aim of this contribution is to provide a comprehensive presentation of the stratigraphic, architectural and artefactual remains exposed at Kition-Bamboula that provide crucial new data for the transitional 12th-to-11th century BC horizon. In particular, through the contextual analysis of well-stratified pottery remains, the study aims to discuss the transformations observed on the island’s ceramic repertoire and especially as regards the impact of the endorsement of wheel-made technology for the production of ceramic finewares. The study will also elucidate the extra-insular connections maintained by the cosmopolitan harbour town at Kition, based on the analysis of the plethora of Levantine maritime transport amphorae contained within the settlement’s pertinent levels. Finally, this presentation will discuss a series of idiosyncratic phenomena, such as infant jar-burials and purple-dye production, dating to the settlement’s transitional phases of the 12th and 11th centuries BC. Ultimately, our contribution aspires to shed light on the continuities and changes observed on the Cypriot material culture and the transformative capacities of the island’s communities at the dawn of the Early Iron Age.

American Schools of Oriental Research. BASOR 370 (2013): 15–47.

This paper attributes the intricacies of the island's elusive political geography in the Iron Age to inherent factors. It is suggested that the immutable properties of the island's environment and geology, and the segmented politico-economic system employed in the exploitation of its natural assets, fostered both strengths and weaknesses, which became pronounced when the polities were confronted with Mediterranean-wide crises or drastic changes to the prevailing trading model of the time: some polities survived and even thrived in the midst of crisis, while others succumbed or became subordinate polities.

Journal of World Prehistory, 1994

The archaeological record of prehistoric Cyprus is rich, diverse, well-published, and frequently enigmatic. Regarded by many as a "bridge" between western Asia and the Aegean, Cyprus and its past are frequently seen from scholarly perspectives prevalent in one of those two cultural areas. Its material culture, however, differs radically from that of either area. Apart from the early colonization episodes on the island (perhaps three during the pre-Neolithic and Neolithic), evidence of foreign contact remains limited until the Bronze Age (post-2500 B.C.). This study seeks to present the prehistory of Cyprus from an indigenous perspective, and to examine a series of archaeological problems that foreground Cyprus within its eastern Mediterranean context. The study begins with an overview of time, place, and the nature of fieldwork on the island, continues with a presentation and discussion of several significant issues in Cypriot prehistory (e.g., insularity, colonization, subsistence, regionalism, interaction, social complexity, economic diversity), and concludes with a brief discussion of prospects for the archaeology of Cyprus up to and "beyond 2000. "

Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 1986

Summary. During the centuries 1700–1400 BC, the archaeological record of the eastern Mediterranean island of Cyprus shows a number of significant innovations: urban centres with public and ceremonial architecture, differential burial practices, writing, an intensification of metallurgical production and export, extensive trade relations with the surrounding cultures of the eastern Mediterranean, fortifications, ‘mass’burials, and increased finds of weaponry. Documentary evidence from Egypt, the Levant, and the Aegean sheds further light on these developments. These changes represent the transformation of an isolated, village-based culture into an international, urban-oriented, complex society. One of the key questions to consider is why these developments in Cyprus lagged so far (400-1200 years) behind those of the island's neighbours: Egypt, Crete, Syria-Palestine, and Anatolia. Using concepts from development economics and political anthropology, and models developed by archaeologists working on similar problems elsewhere, this study attempts to explain the process of change and innovation apparent in the Cypriot archaeological record of 1700–1400 BC.