This new dwarf planet (see the now out of date "Whatmakes a planet?"below) is the largest object found in orbit around the sunsince the discovery of Neptune and its moon Triton in 1846. It islarger than Pluto, discovered in 1930. Like Pluto, the new dwarf planetis amember of the Kuiper belt, a swarm of icy bodies beyond Neptune inorbit around the sun. Until this discovery Pluto was frequentlydescribed as "the largest Kuiper belt object" in addition to being adwarf planet. Pluto is now the second largest Kuiper belt object,while this is the largest currently known.

The dwarf planet is the most distant object ever seen in orbitaroundthe sun, even more distant thanSedna, theplanetoid discovered almost 2 years ago. It is almost 10 billion milesfrom the sun and more than 3 times more distant than the next closestplanet, Pluto and takes more than twice as long to orbit the sun asPluto.

The dwarf planet can beseen using very high-end amateur equipment, but you need to know whereto look. The best way to find precise coordinates (of this planet, orany other body in the solar system) is with JPL'shorizons system. Clickon "select target" and then enter "2003 UB313" under small bodies.

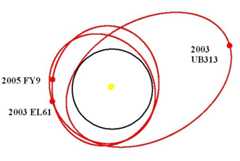

The orbit of the new dwarf planet is evenmoreeccentric than that of Pluto. Pluto moves from 30 to 50 times thesun-earth distance over its 250 year orbit, while the new planet movesfrom 38 to 97 times the sun-earth distance over its 560 year orbit.

Usually when we first discover distant objects in the outer solarsystem we don't know for sure how large they are. Why not? Because allwe see is a dot of light, like the picture at the top of the page. Thisdot of lightis sunlight reflected off the surface of the planet (interestingly thesunlight takes almost a day to get out to the planet, reflect off ofit, and get back to the earth!), but we don't know if the object isbright because it is large or if it is bright because it is highlyreflective or both.

The newest size measurement comesfrom theHubble Space Telescope.While for most telescopes the planet is too small to be seen asanything other than a dot of light, HST can (just barely) directlymeasure how big across it is. The measurement is extremely hard,however, even for HST, because even HST distorts light a little bit asit goes through the telescope, and we needed to be sure that we weremeasuring the actual size of the planet, rather than being fooled bydistortion. So we waited until Eris was very close to a star andthen snapped a series of 28 pictures and carefully went back and forthcomparing the star and the planet. In the end, we determined that Erist is 2400 +/- 100 km across.

The newest size measurement comesfrom theHubble Space Telescope.While for most telescopes the planet is too small to be seen asanything other than a dot of light, HST can (just barely) directlymeasure how big across it is. The measurement is extremely hard,however, even for HST, because even HST distorts light a little bit asit goes through the telescope, and we needed to be sure that we weremeasuring the actual size of the planet, rather than being fooled bydistortion. So we waited until Eris was very close to a star andthen snapped a series of 28 pictures and carefully went back and forthcomparing the star and the planet. In the end, we determined that Erist is 2400 +/- 100 km across.

We study the composition of distant objects by looking at sunlightreflected off of them. The sunlight reflected off the surface of theearth, for example, shows distinct signatures of the oxygen in earth'satmosphere, of photosynthetic plants, and of abundant water, amongotherthings. We have been using theGeminiObservatory on Mauna Kea, Hawaii to study the light reflected fromthe surface of Eris, and have found that the dwarf planetlooksremarkably similar to Pluto. A comparison of the two is shown below,where we show the amount of sunlight reflected in near infrared light.This type of light, just beyond what is visible to thehuman eye, is most sensitive to the types of ices expected on surfaces in the outer solar system.

Pluto and thenew dwarf planet are not completely identical, however. WhilePluto's surface is moderately red, the new dwarf planet appears almostwhite,and while Pluto has a mottled-looking surface which reflects on average60% of the sunlight which hits it, the new planet appears essentiallyuniform and reflects 86% (+/- 7%) of the light that hits it. Thesecharacteristics were not at all expected. In fact, Eris reflectsmore sunlight from its surface than any body in the solar system otherthan Saturn's moonEnceladus,which has active geysers continuously coating the surface infresh frost. We can't think of any source of heat for Eris thatwould cause similar geysers. So what is happening?

Pluto and thenew dwarf planet are not completely identical, however. WhilePluto's surface is moderately red, the new dwarf planet appears almostwhite,and while Pluto has a mottled-looking surface which reflects on average60% of the sunlight which hits it, the new planet appears essentiallyuniform and reflects 86% (+/- 7%) of the light that hits it. Thesecharacteristics were not at all expected. In fact, Eris reflectsmore sunlight from its surface than any body in the solar system otherthan Saturn's moonEnceladus,which has active geysers continuously coating the surface infresh frost. We can't think of any source of heat for Eris thatwould cause similar geysers. So what is happening? We have been conducting an ongoing survey of the outer solarsystem using thePalomar QUESTcamera and theSamuel OschinTelescope atPalomarObservatory inSouthern California. This survey has been operating since the fall of2001, with the switch to the QUEST camera happening in the summer of2003. To date we have found around 80 bright Kuiper belt objects.

To find objects, we take three pictures of a small region of the nightsky over three hoursand look for something that moves. The many billions of stars andgalaxies visible in the sky appear stationary, while satellites,planets, asteroids, and comets appear to move. The image below showsthe three frames taken the night of October 21st, 2003 where we foundthe new planet. Can you find the moving object?

When a new object is discovered the International Astronomical Union(IAU) gives it a temporary designation based on the date it was firstseen. Thus 2003 UB313 can be decoded to tell you that the data fromwhich the object was discovered was obtained in the second half ofOctober 2003. Next, depending on what the object is, the discovererspropose a certain type of permanent name.

Interestingly, there are no actual rules for how to name aplanet (presumably because no one expected there to be more). All ofthe other planets are named for Greek or Roman gods, so anobvious suggestion is to attempt to find such a name for the newplanet. Unfortunately, most of the Greek or Roman god names(particularly those associated with creation, which tend to be themajor gods) were used back when the first asteroids were beingdiscovered. If a name is already taken by an asteroid, the IAU wouldnot allow that name to be used again. One such particularly apt namewould have beenPersephone.In Greek mythology Persephone is the (forcibly abducted) wife of Hades(Roman Pluto) who spends six months each year underground close toHades. The new planet is on an orbit that could be described insimilar terms; half of the time it is in the vicinity of Pluto and halfof the time much further away. Sadly, the name Persephone was used in1895 as a name for the 399th known asteroid. The perhaps moreappropriate Roman version of the name, Proserpina, was used evenearlierfor the 26th known asteroid. The same story can be told for almost anyother Greek or Roman god of any consequence. One exception to this namedepletion is the Roman god Vulcan (Greek Haphaestus), the god of fire.Astronomers have long reserved that term, however, for a oncehypothetical (now known to be nonexistent) planet closer to thesun than Mercury (god of fire, near the sun, good name). We wouldnot want to use such a name to describe such a cold body as our newplanet!

Even after all of these years of debate on the subject of whether ornot Pluto should be considered a planet, astronomers appear no closerto agreement. I wrote extensively about this at the time of thediscovery of Sedna in March 2004. My thoughts have evolved since then,so it might be amusing to seewhatI said 1 1/2 years ago. I have been heavily influenced by writing ascientific review article this summer on the topic of "What is aplanet?" with my colleague Gibor Basri at U.C. Berkeley who I thank forhis insights. The main stumbling block in defining planets in our solarsystem is that, scientifically, it is quite clear that Pluto shouldcertainly not be put in the same category as the other planets. Someastronomers have rather desperately attempted to concoct solutionswhich keep Pluto a planet, but none of these are at all satisfactory,as they also require calling dozens of other objects planets. Whilepeople are perhaps prepared to go from 9 to 10 planets when somethingpreviously unknown is discovered, it seems unlikely that many peoplewould be happy if astronomers suddenly said "we just decided, in fact,that there are 23 planets, and we decided to let you know rightnow." There is no good scientific way to keep Pluto a planetwithout doing serious disservice to the remainder of the solar system.

Culturally, however, the idea that Pluto is a planet is enshrined ina million different ways, from plastic placemats depicting the solarsystem that include the nine planets, to official NASA web sites,to mnemonics that all school children learn to keep the nine planetsstraight, to U.S. postage stamps. Our culture has fully embraced theidea that Pluto is a planet and also fully embraced the idea thatthings like large asteroids and large Kuiper belt objects are notplanets.

In my view scientists should not be trying to legislate an entirelynew definition of the word "planet." They should be trying to determinewhat it means. To the vast majority of society, "planet" meansthose large objects we call Mercury through Pluto. We are then leftwith two cultural choices. (1) Draw the line atPluto and say there are no more planets; or (2) Draw the line at Plutoand say only things bigger are planets. Both would be culturallyacceptable, but to me only the second makes sense for what I think wemean when we say the word planet. In addition, thesecond continues to allow the possibility that exploration will find afew more planets, which is a much more exciting prospect than thatsuggested by the first possibility. We don't think the number ofplanets found by the current generation of researchers will be large.Maybe one or two more. But we think that letting future generationsstill have a shot at planet-finding is nice.

Astronomers tend to dislike this solution as it is clearlynon-scientific. The best analogy I can come up with, though, is withthe definition of the word "continent." The word sound like it shouldhave some scientific definition, but clearly there is no way toconstruct a definition that somehow gets the 7 things we callcontinents to be singled out. Why is Europe called a separatecontinent? Only because of culture. You will never hear geologistsengaged in a debate about the meaning of the word "continent" though.When geologists talk about the earth and its land masses they defineprecisely what they are talking about; they say "continental crust" or"continental drift" or "continental plates" but almost never"continent." Astronomers need to learn something from the geologistshere and realize that there are a few things -- like continents andplanets -- to which people have large emotional attachments, and theyshould not try to quash that attachment.

Thus, we declare that the new object, with a size larger than Pluto,is indeed a planet. A cultural planet, a historical planet. I will notargue that it is a scientific planet, because there is no goodscientific definition which fits our solar system and our culture, andI have decided to let culture win this one. We scientists will continueour debates, but I hope we are generally ignored.

The last week of July 2005 was an exciting one for the outer solarsystem. In the course of two days the existence of three new objectswas announced, and each object was brighter than all of the previouslyknown objects in the Kuiper belt (with the exception of Pluto). With somany bright objects coming out at once it is hard to keep them allstraight. Here is the quick score card:

| object | Eris | 2003 EL61 | 2005 FY9 |

| discoverers | Brown, Trujillo, Rabinowitz | Brown, Trujillo, Rabinowitz | Brown, Trujillo, Rabinowitz |

| size | 2400 +/- 100 km (105% Pluto) | ~3/4 Pluto | ~3/4 Pluto |

| brightness | 4th brightest Kuiper belt object(KBO) | 3rd brightest KBO | 2nd brightest KBO |

| (note that though weconsider Pluto and Eris planets, they are also clearly members ofthe Kuiper belt, with Pluto the brightest member) | |||

| current distance | 97 AU | 52 AU | 52 AU |

| (an AU is thedistance from the earth to the sun) | |||

| orbital period | 560 years | 285 years | 307 years |

| closest approach to sun | 38 AU | 35 AU | 39 AU |

| furthest from sun | 97 AU | 52 AU | 52 AU |

| tilt of orbit compared to planets | 44 degrees | 28 degrees | 29 degrees |

| satellite? | yes! | yes! (two of them!) | no |

| surface composition | Pluto-like | water ice | Pluto-like |

| when visible | late summer, fall, earlywinter | later winter,spring, early summer | |

Here is where these extremely bright Kuiper belt objects are in thesolar system these days:

In mid-July 2005 short abstracts of scientific talks to be given atameeting in September became available on the web (for example,here).We intended to talk about the object now known as 2003 EL61, which wehad discovered around Christmas of 2004, and the abstracts weredesigned to whet the appetite of the scientists who were attending themeeting. In theseabstracts we call the object a name that our softwareautomatically assigned, K40506A (the first Kuiper belt object wediscovered in data from 2004/05/06, May 6th). Using this name turns outto have been a very bad idea on our part! Unbeknownst to us, some ofthetelescopes that we had been using to study this object kept openrecordsof who has been observing, where they have been observing, and whatthey have been observing (these detailed records have since beenremoved from the web). A two-second Google search of "K40506A"immediately reveals one of these observing records. A little playingaround with web addresses then reveals even more records not initiallyGoogleable. Ouch. Bad news for us.Fromthe moment the abstracts became public anyone on the planet with a webconnection, and a little curiosity about this "K40506A" object, and aknowledge of orbital dynamics couldhave found out where it was. Anyone on the planet with even amodest-sized telescope could then go find the object and claim adiscovery as their own.

According to our web server logs, these observing logs were accessedon July 26, 2005 by a computer at the Instituto de Astrofisica inSpain. Less than two days after this computer accessed the observinglogs, the same computer was used to send email officially claiming thediscovery by P. Santos-Sanz and J.-L. Ortiz at the Instituto deAstrofisica (see detailed timelinehere). Atthe time of the announcementwe truly believed that they had no prior knowledge that we had beenobserving the object, and we truly believed that they had not used ourdata to make the announcement of the discovery, but other people foundthe coincidence suspicious.. Shortly after theirannouncement, however, we realized that all of our observingrecords -- including those about what is now known as 2003 UB313, thetenth planet -- were unexpectedly public, and madethe decision to prematurely announce the discovery of 2003 UB313 thatsame afternoon by a press conference. We were unhappy about having toforgo normal scientific protocol and announce the discovery with nocorresponding scientific paper, but under the circumstances we felt wehad no choice.

It is worth asking: if the observing records were on a publiclyaccessible web site, is it wrong to look at them? The obviousanswer is that there is nothing wrong with looking at information onany publicly accessible web site, just as there is nothing wrong withlooking at books in a library. But the standards of scientific ethicsare also clear: any information used from another source must beacknowledged and cited. One is not allowed to go to a library, find outabout a discovery in a book, and then claim that discovery as your ownwith no mention of having read it in a book. One is not evenallowed tofirst make a discovery and then go to the library and realize thatsomeone else independently made the same discovery and then notacknowledge what you learned in the library. Such actions would beconsidered scientifically dishonesty. It is not clear from the timelineprecisely what Ortiz and Santos-Sanz knew or how they used theweb-based records. They wererequired by the standards of science, however, to acknowledge their useofour web-based records if they accessed them. The director of the IAA,Dr. Jose Carlos del Toro Iniesta has promised to investigate whatprecisely happened. We have confidence in Dr. del Toro Iniesta toclarify the situation and determine the appropriate actions.

Some have commented that the real fault here was our own for keepingthe objects "secret." We are saddened by anti-scientific statementslike these, and have alreadywritten extensivelyon why this rather bizarreaccusation is spurious below. The community of scientists condemnsscientists who announce their results publicly before publishingscientific papers. Regardless of the number of times these bizarreaccusations are repeated, we will continue at all times to adhere toaccepted scientific protocol.