Archive

Algorithm complexity and implementation LOC

As computer functionality increases, it becomes easier to write programs to handle more complicated problems which require more computing resources; also, the low-hanging fruit has been picked and researchers need to move on. In some cases, the complexity of existing problems continues to increase.

The Linux kernel is an example of a solution to a problem that continues to increase in complexity, as measured by thenumber of lines of code.

The distribution of problem complexities will vary across application domains. Treating program size as a proxy for problem complexity is more believable when applied to one narrow application domain.

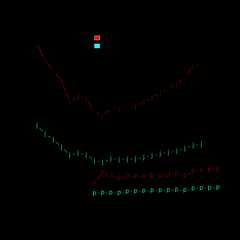

Since 1960, the journalTransactions on Mathematical Software has beenmaking available the source code of implementations of the algorithms provided with the papers it publishes (before the early 1970s they were known as the Collected Algorithms of the ACM, and included more general algorithms). The plot below shows the number of lines of code in the source of the 893 published implementations over time, with fitted regression lines, in black, of the form before 1994-1-1, and

before 1994-1-1, and after that date (black dashed line is aLOESS regression model;code+data).

after that date (black dashed line is aLOESS regression model;code+data).

The two immediately obvious patterns are the sharp drop in the average rate of growth since the early 1990s (from 15% per year to 2% per year), and the dominance of Fortran until the early 2000s.

The growth in average implementation LOC might be caused by algorithms becoming more complicated, or because increasing computing resources meant that more code could be produced with the same amount of researcher effort, or another reason, or some combination. After around 2000, there is a significant increase in the variance in the size of implementations. I’m assuming that this is because some researchers focus on niche algorithms, while others continue to work on complicated algorithms.

An aim ofHalstead’s early metric work was to create a measure of algorithm complexity.

If LLMs really do make researchers more productive, then in future years LOC growth rate should increase as more complicated problems are studied, or perhaps because LLMs generate more verbose code.

The table below shows the primary implementation language of the algorithm implementations:

Language Implementations Fortran 465 C 79 Matlab 72 C++ 24 Python 7 R 4 Java 3 Julia 2 MPL 1 |

Language Implementations Fortran 465 C 79 Matlab 72 C++ 24 Python 7 R 4 Java 3 Julia 2 MPL 1

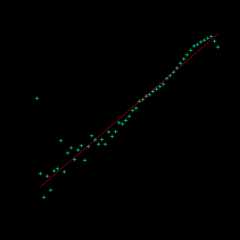

If algorithms are becoming more complicated, then the papers describing/analysing them are likely to contain more pages. The plot below shows the number of pages in the published papers over time, with fitted regression line of the form (0.38 pages per year; red dashed line is aLOESS regression model;code+data).

(0.38 pages per year; red dashed line is aLOESS regression model;code+data).

Unlike the growth of implementation LOC, there is no break-point in the linear growth of page count. Yes, page count is influence by factors such as long papers being less likely to be accepted, and being able to omit details by citing prior research.

It would be a waste of time to suggest more patterns of behavior without looking at a larger sample papers and their implementations (I have only looked at a handful).

When the source was distributed in several formats, the original one was used. Some algorithms came with build systems that included tests, examples and tutorials. The contents of the directories:CALGO_CD,drivers,demo,tutorial,bench,test,examples,doc were not counted.

Distribution of method chains in Java and Python

Some languages support three different ways of organizing a sequence of functions/methods, with calls taking as their first argument the value returned by the immediately prior call. For instance, Java supports the following possibilities:

r1=f1(val); r2=f2(r1); r3=f3(r2);// Sequential calls r3=f3(f2(f1(val)));// Nested calls, read right to left r3=val.f1().f2().f3();// Method chain, read left to right |

r1=f1(val); r2=f2(r1); r3=f3(r2); // Sequential callsr3=f3(f2(f1(val))); // Nested calls, read right to leftr3=val.f1().f2().f3(); // Method chain, read left to right

Simula 67 was the first language to support the dot-call syntax used to code method chains. Ten years laterSmalltalk-76 supported sending a message to the result of a prior send, which could be seen as a method chain rather than a nested call (because it is read left to right; Smalltalk makes minimal use of punctuator characters, so the syntax is not distinguishable).

How common are method chains in source code, and what is the distribution of chain length? Two studies have investigated this question:An Empirical Study of Method Chaining in Java byNakamaru (PhD thesis), Matsunaga, Akiyama, Yamazaki, andChiba, andMethod Chaining Redux: An Empirical Study of Method Chaining in Java, Kotlin, and Python by Keshk, andDyer.

The plot below shows the number of Java method chains having a given length, for code available in a given year. The red line is a fitted regression line for 2018, based on a model fitted to the complete dataset (code and data):

The fitted regression model is:

Why is the number of chains of all lengths growing by around 46% per year? I think this growth is driven by the growth in the amount of source measured. Measurements show that the percentage of source lines containing a method call is roughly constant. In the plot above, the number of unchained methods (i.e., chains of length one) increases in-step with the growth of chained methods. All chain lengths will grow at the same rate, if the source that contains them is growing.

What is responsible for the step change in the number of chains at around 10 methods? Nakamaru classified a random sample of 280 chains, and found that roughly 80% of chains longer than eight methods built an object, e.g., the following chain:

MoreObjects.toStringHelper(this) .add("iLine" , iLine) .add("lastK" , lastK) .add("spacesPending", spacesPending) .add("newlinesPending", newlinesPending) .add("blankLines", blankLines) .add("super",super.toString()) .toString() |

MoreObjects.toStringHelper(this) .add("iLine" , iLine) .add("lastK" , lastK) .add("spacesPending", spacesPending) .add("newlinesPending", newlinesPending) .add("blankLines", blankLines) .add("super", super.toString()) .toString()

Are these chain usage patterns present in Python? The plot below shows the number of Python method chains having a given length, for code available in a given year. The red line is a fitted regression line for 2020, based on a model fitted to the complete dataset (code and data):

The fitted regression model is:

While this model is almost identical to the model fitted to the Java data (the annual growth rate is 39%), the above plot shows a large step change after chains of length two. Keshk’s paper focuses on replicating Nakamaru’s Java results, and then briefly discusses Python. I have an assortment of explanations, but nothing stands out.

Within code, how are method calls split between single calls and a chain of two or more calls?

The fractions in the plot below are calculated as the ratio of chains of length one (i.e., single method call) against chains containing two or more methods. The “j” shows Java ratios, and “p” Python ratios. The red lines show the fraction based on the total number of method calls, and the blue/green lines are based on occurrences of chains, i.e., chain of one vs chain of many (code and data):

The ratio of Java chains containing two or more methods vs one method, grew by around 6% a year between 2006 and 2018, which is only a small part of the overall 46% annual Java growth.

Method chaining is three times more common in Java than Python. In 2020 around a quarter of all method calls were in a chain of two or more, and single method calls were around ten times more common than multi-call chains.

In Python, the use of method chains has roughly remained unchanged over 15 years, with around 5% of all method calls appearing in a chain.

I don’t have a good idea for why method chains are three times more common in Java than Python. Are nested calls the more common usage in Python, or do developers use a sequence of calls communicating using temporary variables?

What of languages that don’t support method chaining, e.g., C. Is the distribution of the number of nested calls (or sequence of calls using temporaries) a power law with an exponent close to 3.7?

Suggestions and pointers to more data welcome.

ISO C++ committee has a new chief sheep herder

The ISO C++ Standards committee,WG21, has a new convenor,Guy Davidson, or rather they will have when the term of the current convenor,Herb Sutter, expires at the end of this year.

Apart from the few people directly involved, this appointment does not matter to anybody (sorry Guy). The WG21 juggernaut will continue on its hedonistic way, irrespective of who is currently the chief sheep herder.

Before discussing the evolution of language standards, a brief summary of the unusual points around this appointment:

- More than one person volunteered for the job (several in the US, who selectedJeff Garland, and one in the UK; everyone agreed that both were capable candidates). The announcement by a programming language convenor that they are not standing again when their 3-year term expires more commonly kicks off discrete discussions about whose arm can be twisted to take on the role. It’s a thankless task that consumes time and money (to attend extra meetings). Also, the convenor has to be neutral, which circumscribes being involved in technical discussion.

Sometimes anoutsider pops up, ruffles a few feathers and then disappears (from the Standards’ world).

- One of theSC22 (the ISO committee responsible for programming languages) convenor selection rules says (seeResolution 14-04): “When a WG Convenorship becomes vacant, … and multiple NBs have each nominated a candidate, the Convenorship shall be assigned to the candidate whose NB currently has the fewest SC 22 Convenors.” Currently, the US holds multiple convenorships and the UK holds none, so the UK nominee is appointed.

As often happens, people like diversity rules until they lose out. The US submitted a selection procedural change to SC22, and asked that it take effect before the selection of a new WG21 convenor. The overwhelming consensus at the SC22 plenary last Monday was not to change the rules while an election was in progress. An ad-hoc committee was set up to consider changes to the current rules.

End of the news and back to regular postings.

Standards committees for programming languages are now a vestige from a bygone era. The original purpose of standards was to reduce costs (the UK focused on savings achieved through repeated use of standardized items and the US focused on reduced training costs) by having companies manufacture products that conformed to a single specification.

There were once a multitude of implementations for the commercially important languages, each supporting slightly different dialects (the differences were sometimes not so slight). Language standards provided a base specification for developers interested in portable code to keep within, and that vendors could be pressured to support.

The spread of Open source compilers significantly reduced the need for companies to invest in maintaining their own compiler (there might be strategic reasons for companies sellinghardware oroperating systems to continue to invest in their own compiler), and reduced the likelihood that customers of commercial compiler companies would continue topay for updates (effectively drivingmost compiler companies out of business).

Language standards are redundant in amonoculture, i.e., where only one compiler per language is widely used. For some years now, there have been a handful ofactively maintained compilers for the widely used languages.

These days,conformance to a language standard is measured by the ability of an implementation to compile and execute the Open source software available in the various ecosystems.

As has often been observed, committees find work to keep themselves busy, and I have seen announcements for new ISO committees that look like they were created because somebody saw a CV padding opportunity.

Icontinue to think that the C++ committee has become a playground for bored consultants looking for a creative outlet.

WG21 meeting attendance continues to grow, now attracting 200+ attendees (Grok undercounts, e.g., 140 vs 215, andChatGPT 5 is completely out of its depth). This is an order of magnitude greater than the C committee,WG14, and in a few years could be two orders of magnitude greater than the other SC22 languages.

The two major C/C++ compiler vendors (i.e., gcc and llvm) could simply go their own way, with regard to new language features. However, I imagine that “supporting the latest version of the language standard” is a great rationale to use when asking for funding.

How large can WG21 become before it collapses under the weight of members and the papers they write?

The POSIX standard,WG15, meetings often had 200-300 attendees in the late 1980s/early 1990s. But the POSIX committee stuck to its goal of specifying existing practice, and so has faded away.

Guy strikes me as an efficient administrator. Which is probably bad news, in the sense that this could enable WG21 to grow a lot larger. What ever happens, it will be interesting to watch.

Predicted impact of LLM use on developer ecosystems

LLMs are not going to replace developers. Next token prediction is not the path to human intelligence. LLMs provide a convenient excuse for companies not hiring or laying off developers to say that the decision is driven by LLMs, rather than admit that their business is not doing so well

Once the hype has evaporated, what impact will LLMs have on software ecosystems?

The size and complexity of software systems is limited by the human cognitive resources available for its production. LLMs provide a means to reduce the human cognitive effort needed to produce a given amount of software.

Using LLMs enables more software to be created within a given budget, or the same amount of software created with a smaller budget (either through the use of cheaper, and presumably less capable, developers, or consuming less time of more capable developers).

Given the extent to which companies compete by adding more features to their applications, I expect the common case to be that applications contain more software and budgets remain unchanged. In a Red Queen market, companies want to be perceived as supporting the latest thing, and the marketing department needs something to talk about.

Reducing the effort needed to create new features means a reduction in the delay between a company introducing a new feature that becomes popular, and the competition copying it.

LLMs will enable software systems to be created that would not have been created without them, because of timescales, funding, or lack of developer expertise.

I think that LLMs will have a large impact on the use of programming languages.

The quantity of training data (e.g., source code) has an impact on the quality of LLM output. The less widely used languages will have less training data. The table below lists the gigabytes of source code in 30 languages contained in various LLM training datasets (for details seeThe Stack: 3 TB of permissively licensed source code by Kocetkov et al.):

Language TheStack CodeParrot AlphaCode CodeGen PolyCoderHTML 746.33 118.12JavaScript 486.2 87.82 88 24.7 22Java 271.43 107.7 113.8 120.3 41C 222.88 183.83 48.9 55C++ 192.84 87.73 290.5 69.9 52Python 190.73 52.03 54.3 55.9 16PHP 183.19 61.41 64 13Markdown 164.61 23.09CSS 145.33 22.67TypeScript 131.46 24.59 24.9 9.2C# 128.37 36.83 38.4 21GO 118.37 19.28 19.8 21.4 15Rust 40.35 2.68 2.8 3.5Ruby 23.82 10.95 11.6 4.1SQL 18.15 5.67Scala 14.87 3.87 4.1 1.8Shell 8.69 3.01Haskell 6.95 1.85Lua 6.58 2.81 2.9Perl 5.5 4.7Makefile 5.09 2.92TeX 4.65 2.15PowerShell 3.37 0.69FORTRAN 3.1 1.62Julia 3.09 0.29VisualBasic 2.73 1.91Assembly 2.36 0.78CMake 1.96 0.54Dockerfile 1.95 0.71Batchfile 1 0.7Total 3135.95 872.95 715.1 314.1 253.6 |

Language TheStack CodeParrot AlphaCode CodeGen PolyCoderHTML 746.33 118.12JavaScript 486.2 87.82 88 24.7 22Java 271.43 107.7 113.8 120.3 41C 222.88 183.83 48.9 55C++ 192.84 87.73 290.5 69.9 52Python 190.73 52.03 54.3 55.9 16PHP 183.19 61.41 64 13Markdown 164.61 23.09CSS 145.33 22.67TypeScript 131.46 24.59 24.9 9.2C# 128.37 36.83 38.4 21GO 118.37 19.28 19.8 21.4 15Rust 40.35 2.68 2.8 3.5Ruby 23.82 10.95 11.6 4.1SQL 18.15 5.67Scala 14.87 3.87 4.1 1.8Shell 8.69 3.01Haskell 6.95 1.85Lua 6.58 2.81 2.9Perl 5.5 4.7Makefile 5.09 2.92TeX 4.65 2.15PowerShell 3.37 0.69FORTRAN 3.1 1.62Julia 3.09 0.29VisualBasic 2.73 1.91Assembly 2.36 0.78CMake 1.96 0.54Dockerfile 1.95 0.71Batchfile 1 0.7Total 3135.95 872.95 715.1 314.1 253.6

The major companies building LLMs probably have alot more source code (as of July 2023, theSoftware Heritage had over unique source code files); this table gives some idea of the relative quantities available for different languages, subject torecency bias. At the moment, companies appear to be training usingeverything they can get their hands on. Would LLM performance on the widely used languages improve if source code for most of the682 languages listed on Wikipedia was not included in their training data?

unique source code files); this table gives some idea of the relative quantities available for different languages, subject torecency bias. At the moment, companies appear to be training usingeverything they can get their hands on. Would LLM performance on the widely used languages improve if source code for most of the682 languages listed on Wikipedia was not included in their training data?

Traditionally, developers have had to spend a lot of time learning the technical details about how language constructs interact. For the first few languages, acquiring fluency usually takes several years.

It’s possible that LLMs will remove the need for developers to know much about the details of the language they are using, e.g., they will define variables to have the appropriate type and suggest possible options when type mismatches occur.

Removing the fluff of software development (i.e., writing the code) means that developers can invest more cognitive resources in understanding what functionality is required, and making sure that all the details are handled.

Removing a lot of the sunk cost of language learning removes the only moat that some developers have. Job adverts could stop requiring skills with particular programming languages.

Little is currently known aboutdeveloper career progression, which means it’s not possible to say anything about how it might change.

Since they werefirst created, programming languages have fascinated developers. They are the fashion icon of software development, with youngsters wanting to program in the latest language, or at least not use the languages used by their parents. If developers don’t invest in learning language details, they have nothing language related to discuss with other developers. Programming languages will cease to be a fashion icon (cpus used to be a fashion icon, until developers did not need to know details about them, such as available registers and unique instructions).Zig could be the last language to become fashionable.

I don’t expect theusage of existing language features to change. LLMs mimic the characteristics of the code they were trained on.

When new constructs are added to a popular language, it can take years before theystart to be widely used by developers. LLMs will not use language constructs that don’t appear in their training data, and if developers are relying on LLMs to select the appropriate language construct, then new language constructs will never get used.

By 2035 things should have had time to settle down and for the new patterns of developer behavior to be apparent.

Evolution has selected humans to prefer adding new features

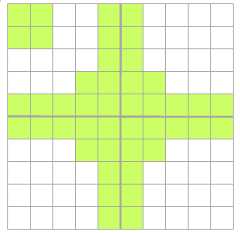

Assume that clicking within any of the cells in the image below flips its color (white/green). Which cells would you click on to create an image that is symmetrical along the horizontal/vertical axis?

In onestudy, 80% of subjects added a block of four green cells in each of the three white corners. The other 20% (18 of 91 subjects) made a ‘subtractive’ change, that is, they clicked the four upper left cells to turn them white (code+data).

The 12 experiments discussed in the paperPeople systematically overlook subtractive changes by Adams, Converse, Hales, and Klotz (a replication) provide evidence for the observation that when asked to improve an object or idea, people usually propose adding something rather than removing something.

The human preference for adding, rather than removing, has presumably evolved because it often provides benefits that out weigh the costs.

There are benefits/costs to both adding and removing.

Creating an object:

- may produce a direct benefit and/or has the potential to increase the creator’s social status, e.g., ‘I made that’,

- incurs the cost of time and materials needed for the implementation.

Removing an object may:

- produce savings, but these are not always directly obvious, e.g., simplifying an object to reduce the cost of adding to it later. Removing (aka sacking) staff is an unpopular direct saving,

- generate costs by taking away any direct benefits it provides and/or reducing the social status enjoyed by the person who created it (who may take action to prevent the removal).

For low effort tasks, adding probably requires less cognitive effort than removing; assuming that removal is not a thoughtless activity.Chesterton’s fence is a metaphor for prudence decision-making, illustrating the benefit of investigating to find out if any useful service provided by what appears to be a useless item.

There is lots ofevidence that while functionality is added to software systems, it is rarely removed. The measurable proxy for functionality is lines of code. Lots ofsource code is removed from programs, but a lot moreis added.

Some companies have job promotion requirements that incentivize thecreation of new software systems, but not theirsubsequent maintenance.

Open source is a mechanism that supports the continual adding of features to software, because it does not require funding. TheC++ committee supply of bored consultants proposing new language features, as an outlet for their creative urges, will not dry up until the demand for developers falls below the supply of developers.

Update

The analysis in the paperMore is Better: English Language Statistics are Biased Toward Addition by Winter, Fischer, Scheepers, and Myachykov, finds that English words (based on theCorpus of Contemporary American English) associated with an increase in quantity or number are much more common than words associated with a decrease. The following table is from the paper:

Word Occurrences add 361,246 subtract 1,802 addition 78,032 subtraction 313 plus 110,178 minus 14,078 more 1,051,783 less 435,504 most 596,854 least 139,502 many 388,983 few 230,946 increase 35,247 decrease 4,791 |

Word Occurrences add 361,246 subtract 1,802 addition 78,032 subtraction 313 plus 110,178 minus 14,078 more 1,051,783 less 435,504 most 596,854 least 139,502 many 388,983 few 230,946 increase 35,247 decrease 4,791

Long term growth of programming language use

The names of files containing source code often include a suffix denoting the programming language used, e.g.,.c for C source code. These suffixes provide a cheap and cheerful method for estimating programming language use within a file system directory.

This method has its flaws, with two main factors introducing uncertainty into the results:

- The suffix denoting something other than the designated programming language.

- Developer choice of suffix can change over time and across development environments, e.g., widely used Fortran suffixes include

.f,.for,.ftn, and .f77(Fortran77 was the second revision of theANSI, and the version I used intensely for several years; ChatGPT only lists later versions, i.e.,f90,f95, etc).

The paper:50 Years of Programming Language Evolution through the Software Heritage looking glass by A. Desmazières, R. Di Cosmo, and V. Lorentz uses filename suffixes to track the use of programming languages over time. The suffix data comes from theSoftware Heritage, which aims to collect, and share all publicly available source code, and it currently hosts over 20 billion unique source files.

The authors extract and count all filename suffixes from the Software Heritage archive, obtaining 2,836,119 unique suffixes. GitHub’slinguist catalogue of file extensions was used to identify programming languages. The top 10 most used programming languages, since 2000, are found and various quantities plotted.

A1976 report found that at least 450 programming languages were in use at the US Department of Defense, and as of 2020 close to 9,000 languages are listed onhopl.info. The linguist catalogue contains information on 512 programming languages, with a strong bias towards languages to write open source. It is missing entries for Cobol and Ada, and its Fortran suffix list does not include.for,.ftn and.f77.

The following analysis takes an all encompassing approach. All suffixes containing at up to three characters, the first of which is alphabetic, and occurring at least 1,000 times in any year, are initially assumed to denote a programming language; the suffixes.html,.java and.json are special cased (4,050 suffixes). This initial list is filtered to remove known binary file formats, e.g., .zip and .jar. Thecommon file extensions listed onFileInfo were filtered using the algorithm applied to the Software Heritage suffixes, producing 3,990 suffixes (the.ftn suffix, and a few others, were manually spotted and removed). Removing binary suffixes reduced the number of assumed language suffixes from 4,050 (15,658,087,071 files) to 2,242 (9,761,794,979 files).

This approach is overly generous, and includes suffixes that have not been used to denote programming language source code.

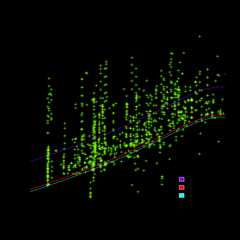

The plot below shows the number of assumed source code files created in each year (only 50% of files have a creation date), with a fitted regression line showing a 31% annual growth in files over 52 years (code+data):

Some of the apparent growth is actually the result of older source being more likely to be lost.

Unix timestamps start on 1 Jan 1970. Most of the 1,411,277 files with a 1970 creation date probably acquired this date because of a broken conversion between version control systems.

The plot below shows the number of files assumed to contain source code in a given language per year, with some suffixes used before the language was invented (its starts in 1979, when total file counts stat always being over 1,000;code+data):

Over the last few years, survey results have been interpreted as showing declining use of C. This plot suggests that use of C is continuing to grow at around historical rates, but that use of other languages has grown rapidly to claim a greater percentage of developer implementation effort.

The major issue with this plot is what is not there. Where is the Cobol, once the most widely used language? Did Fortran only start to be used during the 1990s? Millions of lines of Cobol and Fortran werewritten between 1960 and 1985, but very little of this code is publicly available.

Discussing new language features is more fun than measuring feature usage in code

How often are the features supported by a programming language used by developers in the code that they write?

This fundamental question is rarely asked, let alone answered (my contribution).

Existing code is what developers spend their time reading, compilers translating to machine code, and LLMs use as training data.

Frequently used language features are of interest to writers of code optimizers, who want to know where to focus their limited resources (at least I did when I was involved in the optimization business; I was always surprised by others working in the field having almost no interest in measuring user’s code), and educators ought to be interested in teaching what students are mostly likely to be using (rather than teaching the features that are fun to talk about).

The unused, or rarely used language features are also of interest. Is the feature rarely used because developers have no use for the feature, or does its semantics prevent it being practically applied, or some other reason?

Language designers write books, papers, and blog posts discussing their envisaged developer usage of each feature, and how their mental model of the language ties everything together to create a unifying whole; measurements of actual source code very rarely get discussed. Two very interesting reads in this genre are Stroustrup’sThe Design and Evolution of C++ andThriving in a Crowded and Changing World: C++ 2006–2020.

Languages with an active user base are often updated to support new features. TheISO C++ committee is aims to release a new standard every three years, Java is now on asix-month release cycle, and Python has anannual release cycle. The primary incentives driving the work needed to create these updates appears to be:

- sales & marketing: saturation exposure to adverts proclaiming modernity has warped developer perception of programming languages, driving young developers to want to be associated with those perceived as modern. Companies need to hire inexperienced developers (who are likely still running on the modernity treadmill), and appearing out of date can discourage developers from applying for a job,

- designer hedonism and fuel for the trainer/consultant gravy train: people create new programming languages because it’s something they enjoy doing; some evenleave their jobs to work on their language full-time. New language features provides material to talk about and income opportunities for trainers/consultants.

Note: I’m not saying that adding new features to a language is bad, but that at the moment worthwhile practical use to developers is a marketing claim rather than an evidence-based calculation.

Those proposing new language features can rightly point out that measuring language usage is a complicated process, and that it takes time for new features to diffuse into developers’ repertoire. Also, studying source code measurement data is not something that appeals to many people.

Also, the primary intended audience for some language features is library implementors, e.g.,templates.

There have been some studies of language feature usage. Lambda expressions are a popular research subject, having been added as a new feature to many languages, e.g.,C++,Java, andPython. A few papers have studied language usage in specific contexts, e.g.,C++ new feature usage in KDE.

The number of language features invariably grow and grow. Sometimes notice is given that a feature will be removed from a future reversion of the language. Notice offeature deprecation invariably leads to developer pushback by the subset of the community that relies on that feature (measuring usage would help prevent embarrassing walk backs).

If the majority of newly written code does end up being created by developers prompting LLMs, then new language features are unlikely ever to be used. Without sufficient training data, which comes from developers writing code using the new features, LLMs are unlikely to respond with code containing new features.

I am not expecting the current incentive structure to change.

Memory bandwidth: 1991-2009

TheStream benchmark is a measure of sustainedmemory bandwidth; the target systems are high performance computers. Sustained in the sense of distance running, rather than a short sprint (the term for this is peak memory bandwidth and occurs when the requested data is incache), and bandwidth in the sense of bytes of memory read/written per second (implemented using chunks the size of a double precision floating-point type). Thedataset contains 1,018 measurements collected between 1991 and 2009.

The dominant characteristic of high performance computing applications is looping over very large arrays, performing floating-point operations on all the elements. A fast floating-point arithmetic unit has to be connected to a memory subsystem that can keep it fed with new floating-point values and write back computed values.

The Stream benchmark, inFortran andC, defines several arrays, each containingmax(1e6, 4*size_of_available_cache) double precision floating-point elements. There are four loops that iterate over every element of the arrays, each loop containing a single statement; see Fortran code in the following table (q is a scalar, array elements are usually 8-bytes, with add/multiply being the floating-point operations):

Name Operation Bytes FLOPS Copy a(i)= b(i)160Scale a(i)= q*b(i)161 Sum a(i)= b(i)+ c(i)241 Triad a(i)= b(i)+ q*c(i)242 |

Name Operation Bytes FLOPS Copy a(i) = b(i) 16 0 Scale a(i) = q*b(i) 16 1 Sum a(i) = b(i) + c(i) 24 1 Triad a(i) = b(i) + q*c(i) 24 2

A system’s memory bandwidth will depend on the speed of the DRAM chips, the performance of the devices that transport bytes to the cpu, and the ability of the cpu to handle incoming traffic. The Stream data contains 21 columns, including: the vendor, date, clock rate, number of cpus, kind of memory (i.e., shared/distributed), and the bandwidth in megabytes/sec for each of the operations listed above.

How does the measured memory bandwidth change over time?

For most of the systems, the values for each ofCopy,Scale,Sum, andTriad are very similar. That the simplest statement,Copy, is sometimes a bit faster/slower than the most complicated statement,Triad, shows that floating-point performance is much smaller than the time taken to read/write values to memory; the performance difference is random variation.

Several fitted regression models explain over half of the variance in the data, with the influential explanatory variables being: clock speed, date, type of system (i.e., PC/Mac or something much more expensive). The plot below shows MB/sec for theCopy loop, with three fitted regression models (code+data):

Fitting these models first required fitting a model for cpu clock rate over time; predictions of mean clock rate over time are needed as input to the memory bandwidth model. The three bandwidth models fitted are for PCs (189 systems), Macs (39 systems), and the more expensive systems (785; the five cluster systems were not fitted).

There was a 30% annual increase in memory bandwidth, with the average expensive systems having an order of magnitude greater bandwidth than PCs/Macs.

Clock rates stopped increasing around 2010, butgo faster DRAM standards continue to be published. I assume that memory bandwidth continues to increase, but that memory performance is not something that gets written about much. The memory bandwidth onmy new system is MB/sec. This 2024 sample of one is 3.5 times faster than the average 2009 PC bandwidth, which is 100 times faster than the 1991 bandwidth.

MB/sec. This 2024 sample of one is 3.5 times faster than the average 2009 PC bandwidth, which is 100 times faster than the 1991 bandwidth.

TheLINPACK benchmarks are the traditional application oriented cpu benchmarks used within the high performance computer community.

The 2024 update to my desktop system

I have just upgraded my desktop system. As you can see from the picture below, it is a bespoke system; the third system built using the same chassis.

The 11 drive bays on the right are configured for six 5.25-inch and five 3.5-inch disks/CD/DVD/tape drives, there is a drive cage that fits above the power supply (top left) that holds another three 3.5-inch devices. The central black rectangle with two sets of four semicircular caps (fan above/below) is the cpu cooling tower, with two 32G memory sticks immediately to its right. The central left fan is reflected in a polished heatsink.

Why so many bays for disks?

The original need, in 2005 (well before GitHub), was for enough storage to hold the source code available, via ftp, from various hosting sites that were springing up, hence the choice of theThermaltake Armour Series VA8000BWS Supertower. The first system I built contained six400G Barracuda drives

The original power supply, aThermaltake Silent Purepower 680W PSU, with its umpteen power connectors is still giving sterling service (black box with black fan at top left).

When building a system, I start by deciding on the motherboard. Boards supporting 6+SATA connectors were once rare, but these days are more common on high-end systems. I also look for support for the latest cpu families andhigh memory bandwidth. I’m not a gamer, so no interest in graphics cards.

The three systems are:

- in 2005, anASUS A8N-SLi Premium Socket 939 Motherboard, anAMD Athlon 64 X2 Dual-Core 4400 2.2Ghz cpu, andCorsair TWINX2048-3200C2 TwinX (2 x 1GB) memory. ARed Hat Linux distribution was installed,

- in 2013, an intermittent problem appeared on the A8N motherboard, so I upgraded to anASUS P8Z77-V 1155 Socket motherboard, anIntel Core i5 Ivy Bridge 3570K – 3.4 GHz cpu, andCorsair CMZ16GX3M2A1600C10 Vengeance 16GB (2x8GB) DDR3 1600 MHz memory. Terabyte 3.25-inch disk drives were now available, and I installed two 2T drives. AopenSUSE Linux distribution was installed.

The picture below shows the P8Z77-V, with cpu+fan and memory installed, sitting in its original box. This board and the one pictured above are the same length/width, i.e., theATX form factor. This board is a lot lighter, in color and weight, than the Z790 board because it is not covered by surprisingly thick black metal plates, intended to spread areas of heat concentration,

- in 2024, there is no immediate need for an update, but the 11-year-old P8Z77 is likely to become unreliable sooner rather than later, better to update at a time of my choosing. At £400 theASUS ROG Maximus Z790 Hero LGA 1700 socket motherboard is a big step up from my previous choices, but I’m starting to get involved with larger datasets andrunning LLMs locally. TheIntel Core i7-13700K was chosen because of its 16 cores (I went for a hefty coolerupHere CPU Air Cooler with two fans), along withCorsair Vengeance DDR5 RAM 64GB (2x32GB) 6400 memory. A 4T and 8T hard disk, plus a 2T SSD were added to the storage system. TheLinux Mint distribution was installed.

The last 20-years has seen an evolution of the desktop computer I own: roughly a factor of 10 increase in cpu cores, memory and storage. Several revolutions occurred between the roughly 20 years from thefirst computer I owned (an8-bit cpu running at 4 MHz with 64K of memory and two 360Kfloppy drives) and the first one of these desktop systems.

What might happen in the next 20-years?

Will it still be commercially viable for companies to sell motherboards? If enough people switch to using datacenters, rather than desktop systems, many companies will stop selling into the computer component market.

LLMs perform simple operations on huge amounts of data. The bottleneck is transferring the data from memory to the processors. A system where simple compute occurs within the memory system would be a revolution in mainstream computer architecture.

Motherboards include a socket to support a specialised AI chip, like the empty socket forIntel’s 8087 on theoriginal PC motherboards, is a reuse of past practices.

Agile and Waterfall as community norms

While rapidly evolving computer hardware has been a topic of frequent public discussion since the first electronic computer, it has taken over 40 years for the issue of rapidly evolving customer requirements to become a frequent topic of public discussion (thanks to the Internet).

The following quote is from the Opening Address, byAndrew Booth, of the 1959 Working Conference on Automatic Programming of Digital Computers (published as the first “Annual Review in Automatic Programming”):

'Users do not know what they wish to do.' This is a profoundtruth. Anyone who has had the running of a computing machine,and, especially, the running of such a machine when machineswere rare and computing time was of extreme value, will know,with exasperation, of the user who presents a likely problemand who, after a considerable time both of machine and ofprogrammer, is presented with an answer. He then either haslost interest in the problem altogether, or alternatively hasdecided that he wants something else. |

'Users do not know what they wish to do.' This is a profoundtruth. Anyone who has had the running of a computing machine,and, especially, the running of such a machine when machineswere rare and computing time was of extreme value, will know,with exasperation, of the user who presents a likely problemand who, after a considerable time both of machine and ofprogrammer, is presented with an answer. He then either haslost interest in the problem altogether, or alternatively hasdecided that he wants something else.

Why did the issue of evolving customer requirements lurk in the shadows for so long?

Some of the reasons include:

- established production techniques were applied to the process of building software systems. What is now known in software circles as the Waterfall model was/is an established technique. The figure below is from the 1956 paperProduction of Large Computer Programs by Herbert Benington (Winston Royce’s 1970 paper has become known as the paper that introduced Waterfall, but the contents actually propose adding iterations to what Royce treats as an established process):

- management do not appreciate how quickly requirements can change (at least until they have experience of application development). In the 1980s, when microcomputers were first being adopted by businesses, I had many conversations with domain experts who were novice programmers building their first application for their business/customers. They were invariably surprised by the rate at which requirements changed, as development progressed.

While in public the issue lurked in the shadows, my experience is that projects claiming to be using Waterfall invariably had back-channel iterations, and requirements were traded, i.e., drop those and add these. Pre-Internet, any schedule involving more than two releases a year could be claimed to be making frequent releases.

Managers claimed to be using Waterfall because it was what everybody else did (yes, some used it because it was the most effective technique for their situation, and on some new projects it may still be the most effective technique).

Now that the issue of rapidly evolving requirements is out of the closet, what’s to stop Agile, in some form, being widely used when ‘rapidly evolving’ needs to be handled?

Discussion around Agile focuses on customers and developers, with middle management not getting much of a look-in. Companies using Agile don’t have many layers of management. Switching to Agile results in a lot of power shifting from middle management to development teams, in fact, these middle managers now look surplus to requirements. No manager is going to support switching to a development approach that makes them redundant.

Adam Yuret has anothertheory for why Agile won’t spread within enterprises. Making developers the arbiters of maximizing customer value prevents executives mandating new product features that further their own agenda, e.g., adding features that their boss likes, but have little customer demand.

The management incentives against using Agile in practice does not prevent claims being made about using Agile.

Now that Agile is what everybody claims to be using, managers who don’t want to stand out from the crowd find a way of being part of the community.

Recent Posts

Recent Comments

- Derek Jones onAlgorithm complexity and implementation LOC

- Blaine onAlgorithm complexity and implementation LOC

- Derek Jones onPublic documents/data on the internet sometimes disappears

- Nemo onPublic documents/data on the internet sometimes disappears

- Derek Jones onLifetime of coding mistakes in the Linux kernel

Tags

Archives

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008