Glacial lake outburst floods threaten millions globally

- PMID:36750561

- PMCID: PMC9905510

- DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-36033-x

Glacial lake outburst floods threaten millions globally

Abstract

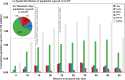

Glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs) represent a major hazard and can result in significant loss of life. Globally, since 1990, the number and size of glacial lakes has grown rapidly along with downstream population, while socio-economic vulnerability has decreased. Nevertheless, contemporary exposure and vulnerability to GLOFs at the global scale has never been quantified. Here we show that 15 million people globally are exposed to impacts from potential GLOFs. Populations in High Mountains Asia (HMA) are the most exposed and on average live closest to glacial lakes with ~1 million people living within 10 km of a glacial lake. More than half of the globally exposed population are found in just four countries: India, Pakistan, Peru, and China. While HMA has the highest potential for GLOF impacts, we highlight the Andes as a region of concern, with similar potential for GLOF impacts to HMA but comparatively few published research studies.

© 2023. The Author(s).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Figures

References

- Roe GH, Baker MB, Herla F. Centennial glacier retreat as categorical evidence of regional climate change. Nat. Geosci. 2017;10:95–99. doi: 10.1038/ngeo2863. - DOI

- Wouters, B., Gardner, A. S. & Moholdt, G. Global glacier mass loss during the GRACE satellite mission (2002–2016).Front. Earth Sci.7, (2019).

- Pachauri, R. K. & Meyer, L.IPCC, 2014: Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation: Special Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change vol. 9781107025, 151 (IPCC, 2014).

- Hock, R. et al. High Mountain Areas. inIPCC SR Ocean and Cryosphere vol. 4 131–202 (Elizabeth Jimenez Zamora, 2019).

LinkOut - more resources

Full Text Sources