Gender and cultural bias in student evaluations: Why representation matters

- PMID:30759093

- PMCID: PMC6373838

- DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0209749

Gender and cultural bias in student evaluations: Why representation matters

Abstract

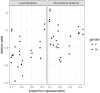

Gendered and racial inequalities persist in even the most progressive of workplaces. There is increasing evidence to suggest that all aspects of employment, from hiring to performance evaluation to promotion, are affected by gender and cultural background. In higher education, bias in performance evaluation has been posited as one of the reasons why few women make it to the upper echelons of the academic hierarchy. With unprecedented access to institution-wide student survey data from a large public university in Australia, we investigated the role of conscious or unconscious bias in terms of gender and cultural background. We found potential bias against women and teachers with non-English speaking backgrounds. Our findings suggest that bias may decrease with better representation of minority groups in the university workforce. Our findings have implications for society beyond the academy, as over 40% of the Australian population now go to university, and graduates may carry these biases with them into the workforce.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Figures

References

- Agresti A. (2001). Analysis of ordinal categorical data. N. J: Wiley.

- Anderson K. and Miller E. D. (1997). Gender and student evaluations of teaching. Political Science and Politics 30(2), 216–219. 10.1017/S1049096500043407 - DOI

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2001). Australian standard classification of education (ASCED)http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/detailspage/1272.02001?opendocument.

- Basow S. A. (1995). Student evaluation of college professors: when gender matters. Journal of Educational Psychology 87(4), 656–665. 10.1037/0022-0663.87.4.656 - DOI

- Benton S. and Cashin W. E. (2011). IDEA PAPER No 50 student ratings of teaching: A summary of research and literature. IDEA Center, Kansas State University.

Publication types

MeSH terms

LinkOut - more resources

Full Text Sources