Justice, Inequality, and Health

Among American men, there is a 14.6 year difference in life expectancybetween the top 1% and the bottom 1% of the income distribution(Chetty et al. 2016). Among American women, the correspondingdifference is 10.1 years. In a recent survey, 38.2% of U.S.respondents in the bottom third of the income distribution reportedfair or poor health, compared to 21.4% of respondents in the middlethird, and 12.3% of respondents in the top third (Hero, Zaslavsky,& Blendon 2017). These disparities were reduced but not eliminatedby adjustment for health insurance status.

Americans also experience health disparities along racial and ethniclines. In 2019, the life expectancy at birth for Hispanic Americanswas 81.8 years, while it was 78.8 years for non-Hispanic whiteAmericans, and 74.7 years for non-Hispanic Black Americans (Arias,Tejada-Vera, & Ahmad 2021). A recent study estimates that theCOVID-19 pandemic disproportionately reduced the life expectancy (atbirth) for Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black Americans from 2018 to2020: 3.88 years for Hispanic Americans, 3.25 years for non-HispanicBlack Americans, compared to 1.36 years for non-Hispanic whiteAmericans (Woolf, Masters, and Aron 2021).

If one turns to the international context, significant inequalities inlife expectancy can be observed between people in low-income andhigh-income countries. In 2016, life expectancy in low-incomecountries was 62.7 years, compared to 80.8 years in high-incomecountries, a gap of 18.1 years (WHO 2020).

On the face of it, these inequalities in life expectancy andself-reported health are seriously unjust. But whether the appearancesof injustice here will withstand close scrutiny is a separatequestion. Not all inequalities in life expectancy seem unjust. Forexample, in 2018, life expectancy for all American women was 81.2years, whereas for all American men it was only 76.2 years (Xu et al.2020). Presumably, little (if any) of this 5 year inequality in lifeexpectancy represents an injustice. However, if some inequalities inhealth are not unjust, then inequalities in health are not unjustper se.

So what makes a health inequality an injustice, when it is one? Dohealth inequalities have some significance in justice thatdiffers from other important inequalities? Or is the injustice of anunjust inequality in health simply due to the application of generalprinciples of equality and justice to the case of health?

To answer these questions, one has to examine two rather differentliteratures. On the one hand, there is an empirical literatureconcerning the underlying determinants of health; on the other hand,there is a philosophical literature concerned with the ethics ofpopulation health. The former literature is considerably moreextensive and developed than the latter. Even there, however, theanswers on offer are hardly complete or fully established.

- 1. Introduction

- 2. A social gradient in health

- 3. Other social determinants of health

- 4. Groups or individuals?

- 5. Causal pathways

- 6. Justice and Domestic Health Inequalities

- 7. Individual Responsibility and Health Behaviors

- 8. Justice and Global Health Inequalities

- Bibliography

- Academic Tools

- Other Internet Resources

- Related Entries

1. Introduction

One possible explanation for health disparities among the rich andpoor is that the rich can afford better health care. Were thisexplanation correct, questions regarding the justice of healthinequalities could be answered by resolving familiar debates aboutaccess to health care.

While unequal access to health care certainly contributes to healthinequalities, epidemiologists argue that the principal causes of theseinequalities lie outside of the health care system. These inequalitiesare largely due to the “social determinants of health”,which we will understand as the socially controllable factors outsidethe traditional health care system that are independent partial causesof an individual’s health status. Candidate examples of thesocial determinants of health include income, education, occupationalrank, racism, and social class (for a brief corrective against thenatural tendency to reserve a privileged position for health carehere, see Marmot 2005).

In this entry, we provide an overview of the empirical literatureregarding the social determinants of health, and the philosophicalliterature concerning the justice of health inequalities. Although thehealth care system is itself a determinant of health, we largely setaside questions regarding access to health care for it is coveredelsewhere (see entry onjustice and access to health care). We begin with a discussion of the social gradient in health, proposedsocial determinants of health, and possible causal pathways by whichthese socially controllable factors could affect people’shealth. We also discuss the normative question of whether healthinequalities should be understood and measured as differences amongsocial groups or differences amongindividuals.

We then address the central question of this entry: what makes ahealth inequality unjust, when it is unjust? We first focus on thejustice of domestic health inequalities, providing an overview ofprominent theoretical approaches to this question. Since many proposethat health inequalities are not unjust when due to the voluntarychoices of individuals, we next explore the issue of individualresponsibility for health and its implications for health policy. Weconclude with a discussion of the justice of global healthinequalities.

2. A Social Gradient in Health

The empirical literature’s most significant and powerfulreported finding can actually be replicated witha number ofthe listed candidate social determinants of health, includingincome, education, occupational rank, and social class. This is theexistence, within a given society, of asocial gradient inhealth. The most significant evidence on the relation between asocially controllable factor and health comes from the Whitehallstudies, conducted in England by Michael Marmot and his colleagues(1978). In these studies, the candidate social determinant of healthis occupational rank.

Between 1967 and 1969, Marmot examined some 18,000 male civil servantsaged between 40 and 69 years old. By placing a flag on their recordsat the National Health Service (NHS) Central Registry, Marmot was ableto track the cause and date of death for each subject who later died.His data are unusually good data. To begin with, they are generatedfrom data-points on specific individuals. Each datum reports therelation between the occupational rank of a particular person and thelife-span (and cause of death) of the very same person. By contrast,almost every other study begins from aggregate data. In addition, anumber of important background factors are held constant for thisstudy population. Notably, all the subjects in this study are stablyemployed, they live in the same region (greater London), and all havefree access to health care provided by the NHS.

Figure 1. Social gradient in totalmortality, Whitehall 25 year follow-up. (van Rossum et al. 2000: 181)[Anextended description of figure 1 is in the supplement.]

Figure 1 presents the Whitehall data after 25 years of follow-up. It reportsage adjusted all-cause mortality rate ratios by employment grade, forthree periods of follow-up. A mortality rate ratio reports theproportion of deaths in a given group divided by the proportion ofdeaths in the reference group. There are four grades in the BritishCivil Service employment hierarchy: administrative (highest),professional/executive, clerical, and “other” (lowest).The professional/executive grade has been used as the reference group,so its mortality rate ratio is 1.0 by definition.

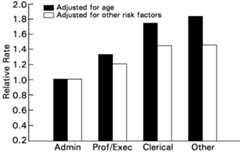

Figure 2. Risk factor adjusted socialgradient in CHD mortality, Whitehall 25 year follow-up. (Marmot 2000:363, fig. 10) [Anextended description of figure 2 is in the supplement.]

The striking and important feature of these data is that therelationship between employment grade and mortality exhibits a markedgradient. It is natural to think that, below some thresholdof deprivation, there will be disproportionate ill-health. Yet, inthis study population, there is no deprivation, not even in the lowestgrade (where everyone is still a government employee with free accessto health care). Furthermore, and notably, there is no threshold.Rather, there is astep-wise improvement in health outcomesas one climbs the employment grade ladder. In addition, thesegradients persist even after the mortality rates have been adjustedfor standard risk factors. For example, coronary heart disease (CHD)accounted for 43 percent of the deaths in the Whitehall study at 10years of follow-up (Marmot, Shipley, & Rose 1984: 1003). Standardrisk factors for CHD include smoking, blood pressure, cholesterol andblood sugar levels, and height.Figure 2 presents the Whitehall data on mortality from CHD after 25 years offollow-up. It reports relative rates of death from CHD by employmentgrade, with administrators having a rate of 1.0 by definition. Theleft bar in each pair displays the relative rate adjusted for agealone, while the right bar adjusts it for all the standard riskfactors. Correcting for standard risk factors does explain some of thegradient in CHD mortality, but no more than a third. The remaininggradient is still marked.

3. Other Social Determinants of Health

The existence of a social gradient in health certainly suggests thatsomething in addition to health care exercises a powerfulinfluence on an individual’s health—something, moreover,that at least correlates with a social variable. However, it is notclear exactly what this something is. To begin with, similar domesticgradients in individual life expectancy can be found when the socialvariable isincome (Chetty et al. 2016; Case, Lubotsky, &Paxson 2002; McDonough et al. 1997); when it iseducation(Mackenbach et al. 2008; Huisman et al. 2005; Crimmins & Saito2001; Elo & Preston 1996; Kunst & Mackenbach 1994); when it issocial class (Wilkinson & Marmot 2003); and, in the U.S.context, when it israce (Arias 2016; Braveman, Cubbin, etal. 2010).

By itself, therefore, the surface fact of a social gradient in healthis compatible with quite different accounts of the underlying causalinfluences on individual health. Each distinct social variable mightfunction as a “marker” for a different underlying causalfactor, different social variables might function instead asalternative markers for the same underlying causal factor, or theremay be some mixture of both. It is also possible that some socialvariables—e.g., education (see Cutler, Lleras-Muney, & Vogl2011)—function as a relatively direct causal factor.

Furthermore, it is not clear how much of the correlation betweenhealth and a given social variable is properly causal in the firstplace. In some cases, there is clearly some “reversecausation” between health and a social variable, notably frompoor health to lower income (Bleakley 2010; J. Smith 2009; Deaton2002) and from poor health to less education and lower occupationalrank (Case, Fertig, & Paxson 2005). Similarly, there is evidenceof a bidirectional relationship between income and mental illness(Ridley et al. 2020). In addition, there is plainly some causationamong social variables, notably from education both to higher incomeand to higher occupational status. Similarly, while there is evidencethat racism contributes directly to poorer health outcomes amongracial and ethnic minorities, for example, by means of racism-relatedstress, it also contributes to racial and ethnic minorities havinglower incomes, worse educational outcomes, and lower occupationalstatus (Williams, Lawrence, & Davis 2019).

The choice of the social variable in terms of which to describe somesocial gradient in health can be made on a number of differentgrounds. One obvious ground would be to choose the variable(s) thatcame closest to conveying the operative causal mechanism(s). Anotherground would be to choose the variable(s) that have independent moraland/or political significance, such as race and gender. These groundsneed not exclude each other and there may be a case for choosing thesame variable on both grounds. The second ground acquires a specialrelevance if health inequalities suffered by individuals who alsosuffer, for example, from racial discrimination are more unjust thanhealth inequalities (of the same magnitude) suffered in the absence ofracial discrimination. If one injustice can compound another, then thechoice of social variable may affect thekind of inequalityin health at issue, and not simply its magnitude.

When the social variable isincome, there is an importantfurther definitional dispute to consider. Income appears to have asignificant effect on life expectancy, even controlling for education(Backlund, Sorlie, & Johnson 1999). However, there is an on-goingdebate about which definition of “income” is adequate tocapture the contribution individual income makes to individual lifeexpectancy (see the sample of articles collected in Kawachi, Kennedy,& Wilkinson 1999). According to theabsolute incomehypothesis, the contribution income makes to individual lifeexpectancy is entirely a function of the individual’snon-comparative income. By contrast, therelative incomehypothesis holds, roughly, that an individual’s lifeexpectancy is also a function of therelative level of herincome—that is, its level compared to others’ income inher society—and not simply of its non-comparative level(Wilkinson 1996). To make this second hypothesis precise requires one,among other things, to specify the reference group to which theindividual’s income is compared and also the nature of thecomparison (for examples, see Deaton 2003). For an overview of thisdebate and the state of evidence, see Sreenivasan (2009a) and Pickettand Wilkinson (2015).

4. Groups or Individuals?

Our discussion thus far has implicitly proceeded on the assumptionthat inequalities in health are defined in terms of membership in somesocialgroup or other. An “inequality” in health,so defined, is a difference between the health status of two groups,with the identity of the group following from the choice of the socialvariable with which health is correlated. For example, we note abovethat in 2019, the life expectancy was 78.8 years for non-Hispanicwhite Americans, and 74.7 years for non-Hispanic Black Americans.While this is how most of the discussion in the literature on healthinequalities is actually structured, the definition is controversial.Notably, Murray, Gakidou, and Frenk (1999: 537) argue in favor of analternative methodology, in which “health inequality”refers to “the variation in health status across individuals ina population”, rather than to a difference in health statusbetween social groups.

Stimulated in large part by their article and the reaction to it,another lively debate considers the basic conceptual question of howhealth inequalities should be defined in the first place (for a niceoverview, see Asada 2013). Should they be defined across socialgroups? Or across individuals instead? It helps to consider thisquestion on two separate levels. Let us call the first one the“fundamental moral level” and let us assume that, on thislevel, the individual is the basic unit of concern. The question atthis first level asks whether it is health inequalities acrossindividuals or health inequalities across groups which matter from thestandpoint of justice.

Now it may seem as if the assumption that individuals are the basicunits of moral concern compels us to define “healthinequality” across individuals as well, i.e., to reject theconventional definition at the fundamental moral level, but that is amistake. Daniel Hausman’s (2007, 2013) position in the debateillustrates this point well. Despite affirming that the individual isthe fundamental unit of moral concern and taking as his starting pointthe claim that what matters most for egalitarians like him isinequalities in welfare or standing among individuals, he stillopposes defining inequalities in health across individuals.Hausman’s (2013: 95) central claim is that “[individual]health inequalities are not themselves pro tantoinjustices”.

For ease of exposition, let us follow Hausman in assuming, morespecifically, that what is of fundamental concern to justice isindividualwell-being. Hausman’s main point can then beformulated as follows: Even though health is both an importantcomponent and cause of well-being, if two individuals are unequal inhealth, it does not follow that they are unequal in well-being. Forobviously, the same two individuals may also be unequal in some othercomponent of well-being, and the individual who is less healthy maynot have less well-being overall. For example,A may behealthier thanB, butB may have more friends or bemore accomplished thanA (or both), and the latter inequalitymay have a greater magnitude than the former (or a greater importanceto well-being), so that the less healthyB may still bebetter off overall thanA (cf. Hausman 2007: 52). The healthinequality betweenA andB is therefore fullyconsistent with there being no fundamental complaint of justice abouttheir comparative situation (at least, not on behalf of the lesshealthyB). Hence, if permission to infer that an injusticeobtains is built into the classification “inequality”, asHausman at least implicitly supposes, we should not classify anyhealth difference betweenA andB (or, moregenerally, between individuals) as an inequality. While Hausmanfocuses on well-being moreover, this point generalizes to manynon-welfarist egalitarian views of justice too, for example, aresourcist view which understands health to be one among a number ofresources.

Of course, even on its own terms, the logic of this argument admits ofan important exception: anytime an inequality in health betweenindividuals is such that itcannot be counter-balanced by anycomplementary inequality in (one or more) other components ofwell-being—for example, because it is too large (Hausman 2007:54)—then that inequality in health does permit us to infer thatthe less healthy individual also has less well-being overall. Hausmancalls these special health inequalities “incompensable”and he accepts that they are immune to his objection:

Data concerning incompensable health inequalities do permit inferencesconcerning inequalities in welfare or standing, and they thus providerelevant information for egalitarians. (Hausman 2013: 98)

Accordingly, he restricts the scope of his official argument, so thatit only concernscompensable health inequalities betweenindividuals.

By contrast to (compensable) health inequalities between individuals,health inequalities between socialgroups typically do, inHausman’s view, permit inferences about inequalities in overallwell-being. Since that is his argument for defining “healthinequality” across social groups, it actually relies on theassumption that individual well-being is the fundamental unit of moralconcern.

Information about social group health differences will thus often berelevant to conclusions about justice, not because group differencesmatter and individual differences don’t, but because informationabout differences in QALYs between well-studied social groups willoften license conclusions about the fundamental inequalities thategalitarians care about. (Hausman 2007: 50)

An important implication of Hausman’s argument, which we shallsee independent reason to affirm later, is that it is artificial andover-simple to put very much weight on mono-factor normativeprinciples, such as “equality of health-by-itself”.

Iris Marion Young (2001) provides a more direct reason for focusing oninequalities across groups at the fundamental moral level. She agreeswith Hausman that individuals are the basic unit of moral concern, butargues that when claims of justice concern equality, the appropriatefocus is inequalities across groups. The cause of morally troublesomeinequalities, she argues, lies with social structures, wherestructures

refer to the relation of basic social positions that fundamentallycondition the opportunities and life prospects of the persons locatedin those positions. (Young 2001: 14)

Since structures constitute and relate to individuals as members ofsocial groups, group-conscious practices of assessing inequalities arenecessary to identifystructural inequalities: inequalitiesin people’s freedom or wellbeing that are the cumulative effectof social institutions, policies, and the decisions of officials(Young 2001: 15). The social groups to focus on, Young (2001: 15)argues, are those

which we already know have broad implications for how people relate toone another—class, race, ethnicity, age, gender, occupation,ability, religion, case, citizenship status, and so on.

Such structural inequalities are unjust since societies should notstructure their social institutions and policies in ways thatdisadvantage people in the exercise of their freedom or flourishing onthe basis of factors beyond their control (Young 2001: 16).

Young does not focus exclusively on health but Paula A. Braveman,Kumanyika, et al. (2011) provide an account of unjust healthinequalities that is structural in nature. While we use the concept ofhealth disparities above as a stand-in forhealthdifferences, Braveman et al. (2011: S150) understand healthdisparities as those health differences among groups that aresystematically tied to their social disadvantage (Braveman et al.2011: S150):

Health disparities are systematic, plausibly avoidable healthdifferences according to race/ethnicity, skin color, religion, ornationality; socioeconomic resources or position (reflected by, e.g.,income, wealth, education, or occupation); gender, sexual orientation,gender identity; age, geography, disability, illness, political orother affiliation; or other characteristics associated withdiscrimination or marginalization…Health disparities do notrefer generically to all health differences, or even to all healthdifferences warranting focused attention. They are a specific subsetof health differences of particular relevance to social justicebecause they may arise from intentional or unintentionaldiscrimination or marginalization and, in any case, are likely toreinforce social disadvantage and vulnerability.

To put this in Young’s terms, health disparities arestructural health inequalities: health differences due tosocial institutions and policies (see also Goldberg 2012; Powers &Faden 2006, 61).

On the other side of the debate, Kasper Lippert-Rasmussen (2013)argues that we should define “health inequality” acrossindividuals at the fundamental moral level. He first raises tworelated objections to social group definitions which together advancethe point that any group definition will be inherently arbitrary.Lippert-Rasmussen’s first objection is the “intra-groupinequality” challenge, according to which there is no reason totreat health inequalities between groups as being any more unjust thanhealth inequalitieswithin groups. Yet,

for any selection of groups such that [health] inequalities betweentwo groups matter, intragroup [health] inequalities may exist. (2013:57)

Lippert-Rasmussen’s second objection is the“group-identification” challenge. There are any number ofways to sub-divide a given population into groups. Holding theunderlying health facts fixed, different choices of group definitionwill correspond to different inequalities in health (of differentmagnitudes) inhering in the same population. Some explanation iscalled for, then, of the significance in justice of the particularcharacter of one’s favored group definition. What is therelevance to justice, for example, of the apparently artificialboundary demarcating the top 1% of the income distribution in the U.S.from the bottom 1% (our opening illustration of an inequality inhealth)?

Now, as Young (2001) and Braveman, Kumanyika, et al. (2011)illustrate, one obvious option for discharging this explanatoryburden, which Lippert-Rasmussen (2013: 58) also recognizes, is todefine the groups so that they “echo the major social causes ofhealth equality”. He rejects this response however on thegrounds that there is likely to be a mismatch between “groupsidentified by the social causes of health” and “groupsamong whom there are morally relevant health inequalities”(Lippert-Rasmussen 2013: 58). A focus on the former will thereforefail to recognize some number of unjust group health inequalities.

Lippert-Rasmussen (2013: 58) also attacks a central premise that hetakes to underlie arguments for group measures of health inequalities,namely, that

only health inequalities that are the causal result of social factorsare unjust, and only group-based measures of health inequality fitunjust health inequalities.

In contrast to this view, Lippert-Rasmussen argues that there is sucha thing as natural injustice, for example, health inequalities due tobiological processes for which no one is responsible, and individualmeasures of health inequalities are necessary to capture them. Wediscuss this point in more detail below.

Nir Eyal (2018) rejects many of the arguments in support of focusingon health inequalities among groups. However, he offers a number ofmoral reasons to identify and address “status groupinequalities”, that is, health inequalities “betweengroups that are defined along lines of social advantage anddisadvantage” (Eyal 2018: 150). He takes these reasons to becompatible with, if not supported by, Lippert-Rasmussen’sinter-individual egalitarianism. We discuss two here. First, althoughstatus group inequalities are not inherently unfair, they are often“rough indicators” of underlying moral problems, includinginjustices such as racial discrimination or failures of socialsolidarity (Eyal 2018: 159). Eyal argues, second, that status groupinequalities may sometimes function as a proxy for luck egalitarianinjustices. Where status group inequalities exist, for example,inequality in life expectancy between low-income and high-incomegroups, it is likely that members of the disadvantaged group aresubject to circumstances that lessen their responsibility for theoutcomes in question (Eyal 2018: 161–162). Since luckegalitarians hold that inequalities due to unchosen circumstance areunjust, status-group inequalities may often function as proxies forluck egalitarian injustice.

Earlier we said that it was helpful to consider the question ofdefining health inequalities on two levels, where the first level isthe fundamental moral level. The main point behind distinguishinglevels here is simply to clarify that the fundamental moral level isseparate from other levels at which the question can be considered andalso more basic than them. In the first instance, then, it does notmatter much how exactly we describe the second level. We need onlydescribe it as “not the fundamental moral level”. How theother level(s) should be described more specifically will depend onone’s purposes. For example, Yukiko Asada (2013) describes a“policy” level and Lippert-Rasmussen (2013) describes alevel of “principles of regulation”.

At the level of policy-making, Asada (2013: 40–41) reviews twoconsiderations that favor defining health inequalities acrossindividuals and one that favors defining them across social groups.She also proposes a novel approach that attempts to combine the meritsof both. A definition across individuals is favored by the fact thatdata collected on that basis lends itself easily to internationalcomparisons (see also Murray, Gakidou, & Frenk 1999), whereas dataon health inequalities defined across groups can only be comparedbetween two countries if both countries have conceived andoperationalized the relevant groups in the same way (which they oftenhave not). Furthermore, defining health inequalities acrossindividuals does not require any balancing or summary operation inorder to yield conclusions about overall inequalities in health,whereas a definition across groups only yields conclusions aboutoverall inequalities when combined with data from other relevantgroups (e.g., when health inequalities across income groups arecombined with health inequalities across educational groups). On theother hand, a definition across groups is favored by the fact that thesocial variable defining the group (e.g., income or education) oftennaturally suggests a target for policy intervention, whereas adefinition across individuals suggests no such target and is thus“one step removed from policy” (Asada 2013: 41).

5. Causal Pathways

The strategy of aligning the social groups used to define inequalitiesin health with the major social causes of health evidently presupposesthat one knows what those causes are. To determine whether any of thepreviously discussed correlations between individual life expectancyand a social variable is causal, one needs some account of thecausal pathways between candidate social determinants andspecific mortality risk factors. Unfortunately, these pathways are notwell understood (Mackenbach 2019: 49–55; Adler & Newman2002; Adler & Ostrove 1999; R. Evans, Hodge, & Pless 1994).While research in this area remains preliminary, it may be useful todescribe some of the possibilities.

Johan Mackenbach (2019: 62–73) helpfully identifies three groupsof causal pathways between social determinants and health outcomes.The first is childhood environment. Socioeconomically disadvantagedmothers are more likely to have impaired health, have greaterpsychosocial stress, and to engage in unhealthy behaviors duringpregnancy (Mackenbach 2019: 66). Their children are therefore morelikely to experience impaired fetal growth, low birth weight, andpremature birth. Children with disadvantaged parents are also morelikely to be exposed to unfavorable conditions after birth, includinginadequate nutrition and harmful levels of air pollution, which mayexplain why they have worse health outcomes compared to children ofhigh-income parents (Currie 2009; Case, Lubotsky, & Paxson2002).

A second group of causal pathways is lifelong material livingconditions (Mackenbach 2019: 68). Certain conditions of absolutematerial deprivation constitute well-recognized risks for ill healthand mortality, including inadequate nutrition, lack of clean water andsanitation, and poor housing. A very plausible causal pathway runsfrom low levels of non-comparative individual income through thesematerial risk factors to poor health outcomes (Aldabe et al. 2011).Low-income people are also more likely to work physically demandingjobs which expose them to dangerous chemicals (Clougherty, Souza,& Cullen 2010), and reside in neighborhoods featuring poor accessto amenities and increased exposure to environmental risks such as airpollution and toxic waste sites (Brulle & Pellow 2006; Pickett& Pearl 2001).

A third group of causal pathways between social determinants andhealth outcomes is social and psychological factors (Mackenbach 2019:72; Marmot 2004). This group is important for it can explain the abovecited social gradients in life expectancy which were mainly observedin highly developed societies, where the prevalence of absolutematerial deprivation is fairly low. In particular, a significantsocial gradient was observed in the Whitehall studies, where theoccupants of even the lowest occupational rank were nevertheless allstably employed civil servants with free access to health care.

One of the most prominent specific risk factors envisaged as theterminus for a psychosocial pathway is (the effects of)stress. As Eric Brunner and Michael Marmot (2006) explain,the long-term effects of stress differ importantly from its short-termeffects. In the short-term, an individual’s fight-or-flightresponse to external stressors is beneficial insofar as it enablesthem to cope with threats and challenges. Among other things, thisacute stress response involves the activation of neuroendocrinepathways, along which adrenaline and cortisol (e.g.) are released intothe bloodstream. These hormones stimulate psychological arousal (e.g.,vigilance) and mobilize energy, while simultaneously inhibitingfunctions irrelevant to immediate survival (e.g., digestion, growth,and repair). An optimal reactivity pattern is characterized by a sharpincrease in levels of circulating adrenaline (and later, cortisol),followed by a rapid return to baseline once the challenge has passed.Sub-optimal patterns are characterized by elevated baseline levels andslower returns to baseline.

By contrast, the long-term effects of stress—either from overfrequent provocation of acute stress or from chronic stress—canbe physiologically harmful (Brunner & Marmot 2006). Stress-induceddamage is mediated, among other things, by prolonged elevation ofadrenaline and cortisol levels in the blood. Elevated cortisol canlead to the accumulation of cholesterol (e.g., by raising glucoselevels even during inactivity); and elevated adrenaline increases theblood’s tendency to clot, which can add to the formation ofarterial plaques and thereby lead to increased risk of heart diseaseand stroke. Other risks that may be increased by stress-induced damageinclude risks for cancer, diabetes, infection, and cognitivedecline.

A psychosocial pathway running from stress-induced damage—or“allostatic load” (B. McEwen 1998)—has next to betraced to some social factor, preferably one amenable to policymanipulation. Four factors that have attracted considerable attentionare “social rank”, “job control”,“racial discrimination”, and “poverty”.

The most specific evidence on the role ofsocial rank inproducing stress-induced damage comes from studies of non-humanprimates (Brunner & Marmot 2006; R. Evans, Hodge, & Pless1994). In various primate species, social life is organized in termsof clear and stable dominance hierarchies. Robert Sapolsky and GlenMott (1987) found that hierarchies of free-ranging male baboonsexhibit an inverse social gradient both in cortisol elevations and inadverse cholesterol ratios. Manipulating the dominance hierarchy ofcaptive female macaque monkeys, Carol Shively and Thomas Clarkson(1994) similarly found that dominant monkeys who became subordinatehad a five-fold excess of coronary plaques as compared to those whoremained dominant. (Part of this excess was due to the stressassociated simply with achange in social rank [as distinctfrom a demotion], since subordinate monkeys who became dominant alsohad more atherosclerosis [albeit, only twice as much] compared tothose who remained subordinate).

Evidence on the role oflow job control in producingstress-induced damage comes from the Whitehall II study (Marmot,Bosma, et al. 1997). “Job control” refers to anindividual’s level of task control in the workplace,operationalized here in terms of a questionnaire concerning decisionauthority and skill discretion. One of the principal diseases forwhich stress-induced damage increases the risk is coronary heartdisease (CHD). In Whitehall II, there was an inverse social gradientin age-adjusted CHD incidence: Compared to their high gradecounterparts, intermediate grade male civil servants were 1.25 timesmore likely to develop a new case of CHD in a five year interval,while low grade men were 1.5 times more likely. For women, the oddsratios were 1.12 and 1.47. Marmot and his colleagues also found aninverse social gradient in low job control. Among men, 8.7 percent ofhigh, 26.6 percent of intermediate, and 77.8 percent of low gradecivil servants reported low job control; for women, the percentageswere 10.1, 34.8, and 75.3. But their key finding was that asubstantial part of the gradient in CHD incidence could be attributedto the differences in job control. Controlling for low job controlreduced the low grade (e.g.) men’s odds ratio for new CHD from1.5 to 1.18 and the women’s from 1.47 to 1.23. By comparison,known CHD risk factors only reduced the same ratios from 1.5 to 1.3and from 1.47 to 1.35, respectively.

There is also evidence that experiences ofracialdiscrimination may contribute to racial disparities in health.While some racial health disparities are explainable by appeal to thelower average socioeconomic status of racial minorities, racial healthdisparities persist at every level of socioeconomic status (Braveman,Cubbin, et al. 2010). There is increasing evidence that such residualdisparities may in part be the result of experiences ofindividual-level racial discrimination which produce stress-induceddamage (Williams et al. 2019; Colen et al. 2018). Indeed, a recentstudy suggests a causal pathway between these factors, finding anindependent association between discrimination exposure and higherlevels of spontaneous amygdala activity andconnectivity—processes linked to higher levels of stress,physiological arousal, vigilance, and negative health outcomes (Clark,Miller, & Hegde 2018).

Finally, there is increasing evidence that children raised inpoverty are often exposed to adversities that produce“toxic stress”. Such stress “involves the frequentor sustained activation of the biological stress system” and isoften the result of adverse events that are more likely to exist inlow-income households, including maternal depression, child abuse andneglect, and spousal violence (C. McEwen & B. McEwen 2017: 448).Toxic stress in turn negatively affects children’s earlyphysical and cognitive development, with likely negative consequencesfor their later health, educational, and occupational outcomes (C.McEwen & B. McEwen 2017; Boyce, Sokolowski, & Robinson2012).

In sum, there is a reasonable case to be made that many healthinequalities are caused by a number of socially controllable factorsoutside of the traditional health care system. Such socialdeterminants of health may include income, occupational rank,education, social status, and racial discrimination. We would caution,however, that more evidence is needed to establish the proposed causalpathways, and that some of the evidence we discuss is contentious. Forexample, Anne Case and Christina Paxson (2011: F185) argue that muchof the gradient Marmot, Bosma, et al. (1997) attribute to job controlin Whitehall II can be explained by participants’ early lifehealth and socioeconomic status, suggesting that “occupationalgrade may be more of a marker of poorer health than a cause of poorerhealth”.

In addition, while the above evidence regarding causal pathways isarguably sufficient for normative theorizing, things may be differentfor the purposes ofdesigning policy remedies. As AngusDeaton (2002: 15) puts it, “policy cannot be intelligentlyconducted without an understanding of mechanisms; correlations are notenough”. It is not clear that our existing understanding of thecausal pathways between socially controllable factors and specificmortality and morbidity risks is sufficiently well-developed tounderwrite concrete policy proposals. Moreover, even if it were, itwould still be a further step tolicense implementation ofsome such proposal. Among other things, a license of this kindrequires an account of the comparative effectiveness of a proposedreform in relation to salient alternatives.

6. Justice and Domestic Health Inequalities

We turn now to a discussion of the normative dimension of healthinequalities. We begin in this section with a look at healthinequalities among residents of the same state. We first examine theconcept ofhealth equity which is often employed as anormative standard in the public health literature for evaluating suchinequalities. We then turn to the philosophical literature, providingan overview of the most prominent accounts of the justice of healthinequalities. In the two remaining sections of this entry, we firstdiscuss the relevance of individual responsibility for health justicebefore concluding with a discussion of the justice of global healthinequalities.

6.1 Health Equity

The concept ofhealth equity is often used to refer to justdistributions of health, where health inequities are understood to bedifferences or disparities in health that are avoidable, unnecessary,and unfair (Whitehead 1992). Healthinequalities aretherefore in principle observable differences in the health amongindividuals and groups. Healthinequities are healthinequalities that are unjust. (For discussion of the ways in whichhealth inequality metrics may themselves be value-laden see King 2016;see Asada 2019 for a good discussion of challenges in measuring healthinequities).

While the concept of health equity is frequently invoked as anormative standard by scholars, policymakers, and public healthpractitioners, there is a good deal of disagreement regarding itsmeaning. There is disagreement, first, on which health differences areavoidable. Some suggest that health differences are avoidableonly if they are caused by social processes rather than natural orbiological processes (Chang 2002; Whitehead 1992). Others argue thatthis understanding is too constrained (Preda & Voigt 2015; Wilson2011). Even if health differences caused by natural processes are notavoidable in the sense of being preventable, these critics suggest,they may be avoidable in the sense of being treatable. Moreover, ifinequalities in health are inequitable in part because they areunchosen, as luck egalitarians claim, then it makes sense to identifyavoidable health inequalities as those that are amenable tointervention (Preda & Voigt 2015: 30).

There is also disagreement regarding whether avoidability is adistinct and necessary condition of unjust health inequalities. SudhirAnand and Fabienne Peter (2000) suggest that unfairness entailsavoidability and so is not really separate from it. But avoidabilityis cleanly separable (in the other direction) from unfairness, andthat can be an analytic advantage. For example, it allows the justiceof inevitable inequalities in health to be decided without having toengage the issue of fairness at all. Others question whether healthdifferences must be avoidable if they are to count as unjust(Lippert-Rasmussen 2013: 59–60; Wilson 2011: 216). For luckegalitarians, health differences due to natural processes can beunjust regardless of whether they can be prevented or treated. Even ifpersonA has lesser mobility compared to personBdue to a genetic condition that is neither preventable nor treatable,the difference betweenA andB is unjust andA has a claim on society to rectify it, for example, throughthe provision of a mobility aid or the restructuring of the socialenvironment. Such inequalities are examples ofnaturalinjustices—injustices caused by natural processes—ratherthansocial injustices—injustices caused by socialprocesses (Lippert-Rasmussen 2013: 59–60). (For a contrary view,see Wester 2018).

One way to save the avoidability condition—understood asamenability to intervention—is to stipulate that the concept ofhealth equity is only concerned withsocial injustices(Sreenivasan 2015: 54). But, while luck egalitarianism iscontroversial, James Wilson (2011: 216) cautions that it would be amistake to define the concept of health equity in a way thatpresupposes its falsity. Wilson (2011: 217) therefore concludes thathealth inequities are simply those health differences that are unjust(for an excellent overview of these and other debates regarding theconcept of health equity, see M. Smith 2015).

While these debates regarding the avoidability condition implicitlyraise questions of justice, the fairness condition does so explicitly.If the concept of health equity is to function as a defensiblenormative standard, we need an account of justice in the distributionof health.

6.2 Free-Standing Approaches

We can distinguish two fundamentally different approaches to bringingverdicts of fairness or justice to bear on a given health inequality.On thefree-standing approach, the injustice of an unjusthealth inequality is the primary injustice, although a verdict ofinjustice can also be spreadbackwards from this primaryinjustice to its causes. By contrast, on thederivativeapproach, the injustice of an unjust health inequality is not theprimary injustice. Rather, the primary injustice is some unjust causeof a health inequality, although a verdict of injustice can also bespreadforwards from this primary injustice to the healthinequality itself. In this way, the injustice of an unjust healthinequality derives from the primary injustice of its cause(s). (Thisdistinction between free-standing and derivative approaches closelymatches Peter’s [2004: 94–95] distinction between directand indirect approaches). Suppose, for example, that part of thedifference in life expectancy between white and Black men in theUnited States is caused by racial discrimination. On the derivativeapproach, this part of that inequality in health is unjust because itscause is unjust, and this verdict holds even if inequalitiesin health are not otherwise unjust (e.g., even if no valid principleof equality applies directly to health). On a free-standing approach,by contrast, this difference in life expectancy may itself be unjust,regardless of its cause. We discuss each approach in turn.

The simplest example of the free-standing approach applies a generalprinciple of equality directly to the case of health. (For generaldiscussion of the grounds of egalitarianism, as well as of thecharacter of different versions, see the entry onegalitarianism.) With some qualifications, the resultant requirement of“equality of health” is affirmed, for example, by AnthonyCulyer and Adam Wagstaff (1993). This implies thatanyavoidable inequality in health is unfair or unjust.

Luck egalitarians object to the strict equality view on the groundsthat inequalities are not unjust if they are the result of voluntaryand informed choices (Segall 2010; Le Grand 1987). While it is unjustfor one person to be worse off than another because ofbruteluck—i.e., factors beyond a person’s control such as theirnatural or social circumstances—inequalities due tooption luck—i.e., factors within a person’scontrol—are just. For luck egalitarians therefore, not allhealth inequalities are unjust, only those due to unchosencircumstances (Voorhoeve 2019; Albertsen & Knight 2015; Temkin2013; Segall 2010: 99).

A problem for both strict and luck egalitarian views, however, is thatthey are subject to the leveling down objection, for unjustinequalities in health may be addressed either by improving the healthof those who are unfairly worse off or leveling down the health ofthose who are unfairly better off (Segall 2010). IfA’slife expectancy is 10 years shorter thanB’s due tocancer, this inequality may be addressed either by treatingA’s cancer or damagingB’s health.Similarly, if one holds that health inequalities between social groupsare unjust, one may be committed to the conclusion that deteriorationsin the health of members of advantaged social groups are good—atleast in one respect—when they reduce such inequalities. Forexample, one may be committed to the questionable claim that the riseof “deaths of despair” among white Americans in thetwenty-first century (see Case & Deaton 2015, 2020) is in onerespect good since it reduced inequalities in life expectancy amongwhite Americans and Black Americans (for a thoughtful discussion ofthis issue, see Blacksher 2018).

Eyal (2013) offers the most promising response to the leveling downobjection in this context, pointing to a number of cases where it isplausible to prefer outcomes that are more equal, even if less equalalternatives are available where some are better off and no one isworse off. Luck egalitarians also soften the force of this objectionby adopting pluralist views, arguing that comparative fairness is notthe only relevant value (see Voorhoeve 2019; Temkin 2013).

Segall (2010) opts instead for a luck prioritarian account,prioritizing the opportunity for health of the worse off.According to this principle,

Fairness requires giving priority to improving the health of anindividual if she has invested more rather than less effort in lookingafter her health, and of any two individuals who have invested equalamounts of effort, giving priority to those who are worse off(health-wise). (Segall 2010: 112)

On Segall’s (2010: 119), view therefore, justice demands, first,that we improve the health of those who have been most prudent intaking care of their health, that is, whose health deficits are mostdue to brute luck. For individuals who have exercised equal prudenceregarding their health, justice demands, second, that priority begiven to those whose health deficit is greatest—i.e., are worseoff (Segall 2010: 119). In contrast to a luck egalitarian view,Segall’s (2010: 120) luck prioritarian view is not concernedwith realizing equality in health, but rather with “prioritizingthe opportunity for health of the worse off”.

Some scholars avoid the leveling down objection by opting for socialor relational egalitarian alternatives to luck egalitarianism. On thisview, health inequalities are unjust if they undermine citizens’ability to interact with each other as equals (see Voorhoeve 2019;Kelleher 2016; Voigt & Wester 2015; Hausman 2012; Pogge 2004). Forexample, Alex Voorhoeve (2019) suggests that social egalitarians havespecial reason to be concerned with health deficits that make peoplevulnerable to domination or exploitation in private life as well asdomination or marginalization in public life. Proponents of this viewargue that it addresses a significant problem with luck egalitarianapproaches since it holds that health inequalities due topeople’s voluntary and informed choices are nonetheless unjustif they undermine their standing as equals. A challenge to social orrelational egalitarian views, however, is that they are vague on whichhealth inequalities undermine equal relations among citizens (Hausman2019; Voigt & Wester 2015).

In contrast to those who see luck egalitarian and relationalapproaches as competing views, Voorhoeve (2019) argues that each has acompelling basis and may be combined in a complementary way. Social orrelational egalitarianism recognizes that there is “reason to beaverse to choice-based inequalities that threaten people’sstatus as equal citizens” while the luck egalitarian approachoffers a reasonable interpretation of the vague relational requirementof the principle of equal consideration (Voorhoeve 2019:154–155).

Others avoid the leveling down objection by defending sufficientarianapproaches to health justice (for comprehensive discussions ofsufficientarian approaches, see Fourie 2016; Rid 2016). Madison Powersand Ruth Faden (2006: 15–29) argue that social justice requiresthat people be secured a sufficient level of wellbeing where wellbeingis understood to have six essential dimensions: health, personalsecurity, reasoning, respect, attachment, and self-determination.Justice does not therefore demand equality in health outcomes, butrather that people have “enough health over a long enough lifespan to live a decent life” (Powers & Faden 2006: 95).Jennifer Prah Ruger (2010) similarly develops a capabilities approachto health justice, according to which people are entitled to athreshold level of certain core health capabilities, that is,abilities to be healthy. The focus of public policy, Prah Ruger (2010:88–90) argues, should be to reduce “shortfall”inequalities—i.e., to bring people as close to the requisitethreshold as is possible.

While these sufficientarian approaches avoid the leveling downobjection, they nonetheless face two significant challenges. First,should governments be indifferent regarding health disparities abovethe threshold identified by sufficientarian views (Arneson 2002)? Ifthe threshold is set too low, such a view may regard significantdisparities in morbidity and mortality as not unjust. Second, amongthose who fall below the threshold, who should be prioritized (Fourie2016)? Should policymakers focus on maximizing the number of peoplewho meet the threshold, even if this means helping those who arebetter off? Or should they prioritize the worse off, even if thismeans using significant resources to only marginally improve theirhealth? (For a discussion of possible solutions to these problems, seeShields 2016).

Some commentators criticize free-standing views’ tendency tofocus on or prioritizehealth inequalities to the exclusionof other normative considerations. Hausman (2007, 2013, 2019) arguesthat health inequalities among individuals are not pro tanto unjustsince such inequalities (among individuals) do not permit inferencesregarding inequalities in wellbeing or moral standing which are ofreal moral concern. Daniel Weinstock (2015: 438) cautions against“health consequentialism”, the view that all socialdeterminants of health should be arranged to achieve some preferreddistribution of health—e.g., health equality. He argues insteadin favor of pluralistic approaches to distributive justice whichrecognize that the distribution of many of the social determinants ofhealth—e.g., income and education—should also be governedby additional, non-health related principles of justice (see alsoWester 2018). Powers and Faden’s (2006) view avoids theseproblems by positing six dimensions of wellbeing, though this approachfaces the challenge of how conflicts among these dimensions ought tobe adjudicated.

6.3 Derivative Approaches

In contrast to free-standing approaches to the justice of healthinequalities, derivative approaches locate the injustice of unjusthealth inequalities with their unjust causes. Norman Daniels (2008)offers the most prominent example of this approach (see also Daniels,Kennedy, & Kawachi 2000; and Peter 2004). His central claim isthat, by a happy coincidence, John Rawls’ principles of justiceregulate all of the principal social determinants of health (Daniels2008: 82 and 97). Compliance with these principles, Daniels (2008: 82)claims, “will consequently flatten the socioeconomic gradient ofhealth as much as we can reasonably demand” with the result that“social justice in general is good for population health andits fair distribution”.

To begin with,income andworkplace organization areregulated by the difference principle: inequalities in income andhierarchies in the workplace are permitted only to the extent thatthey work to the greatest benefit of the least well off.Education is regulated by the principle of fair equality ofopportunity, which requires “equitable public education”as well as “developmentally appropriate day care and earlychildhood interventions” (Daniels 2008: 96).Politicalparticipation, which Daniels (2008: 95–6) regards as asocial determinant of health, is regulated by the principle of equalbasic liberty: among other things, this principle safeguards the fairvalue of the right to participate politically. Finally, reaffirminghis earlier work (1985), Daniels maintains that fair equality ofopportunity also requires universal access to comprehensivehealthcare (broadly construed to include public health).

To the extent that these social variables are causal determinants ofhealth, and to the extent that their distribution in societyfails to conform to the corresponding principle of Rawlsianjustice, the resultant health inequalities will be unjust and unjustbecause their causes are unjust. The flip-side of this point is thatthe implementation of Rawls’ principles will tend—again,insofar as the relevant determinants are causal—to reduceexisting inequalities in health (Daniels 2008: 82).

As Daniels notices, observing Rawlsian justice may flatten the socialgradient in health without eliminating it altogether. For example, thedifference principle may permit certain inequalities of income, whichare neverthelesspossible to eliminate. If income is a causaldeterminant of health, these permissible income inequalities will(continue to) generate health inequalities if they are left in place.(This scenario is actually only coherent if therelativeincome hypothesis is the correct account of the causal mechanism. Forthe explanation, see Sreenivasan 2009b). Daniels holds that thepersistence of avoidable health inequalities does not give us reasonin justice, independently of the difference principle, to eliminatetheir underlying cause. In his view, justice permits some avoidableinequalities in health:

The residual inequalities that emerge with conformance to[Rawls’] principles are not a compromise with what justiceideally requires; they are acceptable as just. (2008: 99)

Anand and Peter (2000) criticize Daniels’ account on the groundsthat there is a tension between two different uses Daniels makes ofRawls’ second principle of justice. On the one hand, they argue,Daniels treats its two parts as simply regulating certain specificsocial determinants of health—the fair equality of opportunityprinciple regulates education (e.g.), while the difference principleregulates income. On the other hand, his account of health care treatsthe fair equality of opportunity principle as regulatinghealth itself directly. But the latter employment of fairequality of opportunity, which Anand and Peter actually prefer (2000:52), threatens to contradict Daniels’ treatment of residualhealth inequalities. If fair equality of opportunity requires (somekind of) egalitarianism about health, then residual healthinequalities that remain after the difference principle is fullyimplemented may still fall withinits scope. In that case,Rawlsian justice may well command their reduction.

To avoid this problem of inconsistency, Jayna Fishman and DouglasMacKay (2019) and Johannes Kniess (2019) rework Rawls’s theoryof justice, developing a Rawlsian conception of the socialdeterminants of health—thesocial bases ofhealth—and arguing that it should be considered a socialprimary good. Fishman and MacKay (2019) and Kniess (2019) disagreehowever on which Rawlsian principle should govern the distribution ofthis good. Fishman and MacKay (2019) argue that the parties to theoriginal position would choose an additional principle of justice togovern the distribution of the social bases of health and assign itlexical priority over fair equality of opportunity and the differenceprinciple. According to this principle, the

social bases of health are to be arranged so as to have the greatestpositive impact on the health status of those least advantaged on thesocial health gradient. (Fishman & MacKay 2019: 616)

The social bases of health deserve this priority, Fishman and MacKay(2019: 615) suggest, since health is necessary if people are torealize their highest order interests in developing and exercisingtheir two moral powers. Inequalities in the distribution of the socialbases of health, and so inequalities in health status resulting fromsuch a distribution, are just if the least advantaged on the socialhealth gradient have a higher expected health status than they wouldunder an equal distribution (Fishman & MacKay 2019: 616). Kniess(2019: 418), by contrast, argues that the social bases of healthshould be governed by the difference principle, though he concedesthat this complicates the indexing problem, namely, that there is noobvious way to rank different distributions of income and wealth, thepowers and prerogatives of offices and positions of responsibility,and the social bases of health. Kniess (2019: 420) concludes that suchtradeoffs must be decided through the democratic process. WhileFishman and MacKay (2019) avoid this problem by prioritizing thesocial bases of health, as Kniess argues (2019: 418–420), hisapproach may be preferable since it permits tradeoffs between healthand income and also leaves more room for political communities to setpriorities.

One remaining problem with Fishman and MacKay (2019) andKniess’s (2019) reworking of Daniels’ (2008) approach isthat they too are silent on the justice of residual healthinequalities. This question is important, for while we have presentedthe free-standing and derivative approaches as alternatives, it ispossible for the two approaches to be combined. Holding thatinequalities in health are unjust because of their unjust causes doesnot preclude holding that they are unjust simply qua inequalities.

7. Individual Responsibility and Health Behaviors

Insection 5, we identified three groups of possible causal pathways between socialdeterminants and health outcomes: childhood environment, materialliving conditions, and social and psychological factors. A centralcontributing factor to poor health outcomes, however, has an ambiguousrelation to social determinants. There is strong evidence thathealth behaviors, including smoking, excessive alcoholconsumption, poor nutrition, and lack of physical exercise are keycontributors to morbidity and mortality (Petrovic et al. 2018). Somefind, moreover, that health behaviors explain much of the socialhealth gradient in high-income countries, since harmful healthbehaviors are more prevalent in groups with lower socioeconomic status(Petrovic et al. 2018). For example, Silvia Stringhini, Sabia, et al.(2010) argue that when superior measures of health behaviors areemployed, much of the health gradient identified in the Whitehall IIstudy can be explained by a social gradient in harmful healthbehaviors (though Stringhini, Dugravot, et al. [2011] did notreplicate this finding in a study of employees of the French nationalgas and electric company, suggesting that whether health behaviorscontribute to the social gradient may depend on social context).

When harmful health behaviors are more prevalent among people withlower socioeconomic status, one might argue that the consequent healthinequalities are simply the result of social factors over which onehas no control—i.e., as akin to one’s childhoodenvironment. This is too quick, however, for peopledecide—at least in some sense—to smoke, to drinkalcohol excessively, or to eat a poor diet, and such decisions may notalways be determined by social factors—e.g., materialconstraints on access to healthy food. This matters for evaluations ofjustice, since, as we saw above, some argue that health inequalitiesare not unjust if they are the result of voluntary choices. Ifdecisions to engage in harmful health behaviors meet the appropriatethreshold of voluntariness, therefore, one may plausibly argue thatthere is nothing unjust about that portion of the social gradient inhealth that is due to them.

The question of individual responsibility is also relevant for anumber of areas of health policy. If individuals are responsible forthe downstream consequences of their harmful health behaviors,policymakers may be justified in withholding care or assigning suchpatients lesser priority in the allocation of scarce resources (seeVoigt 2013). Policymakers may also be justified in designing publichealth strategies that encourage people to make better choicesregarding diet and physical exercise as opposed to addressing thestructural circumstances within which people make choices.

To begin, luck egalitarians would seem to be committed to the viewthat health inequalities due to voluntarily chosen health behaviorsare not unjust. While luck egalitarians hold it is unjust for oneperson to be worse off than another because of brute luck,inequalities due to option luck—i.e., factors within aperson’s control—are just. Applied to health and healthcare, luck egalitarianism would seem to imply that people should becompensated for inequalities in health due to brute luck—e.g.,genetic factors and the social determinants of health—but heldresponsible for health outcomes due to option luck—e.g.,voluntary decisions to drink excessively or eat a poor diet (see,e.g., Le Grand 1987, Segall 2010, and Cavallero 2011).

For example, if someone has a treatable case of lung cancer, we mightordinarily reasonably presume that it would be unjust to deny himmedical care. However, if his cancer is due to a heavy, life-longsmoking habit, the question arises of whether the ordinary presumptionis defeated or diminished in strength. For instance, if there is achoice to be made (say, because of resource scarcity) between treatinghim and treating another lung cancer patient who is in no wayresponsible for her lung cancer, does justice require preferring thesecond patient? A simple application of luck egalitarianism would holdthat it is just to deny treatment to the smoker, as long as his“decision to smoke” qualifies as a “voluntarychoice” according to some suitable criteria.

Many find this implication of luck egalitarianism to be objectionable,with Elizabeth Anderson (1999: 296) calling it “the problem ofabandonment of negligent victims”. Some luckegalitarians respond that their view, properly understood, is notcommitted to this implication. For example, Alexander Cappelen and OleNorheim (2005) and Julian Le Grand (2013) suggest that differences inoption luck—i.e., differences in how the voluntary choices ofpeople play out—are themselves unjust, and so policies should beimplemented to ensure that the lucky help the unlucky, such as taxeson cigarettes with the revenues used to provide care to smokers whodevelop lung cancer. Eric Cavallero (2011: 393–396) takes astronger line, arguing that luck egalitarianism provides no supportfor holding individuals accountable for the outcomes of healthbehaviors. Cavallero (2011: 393) distinguishes between sociallydetectable and socially undetectable risky behaviors, with smoking anexample of the former and poor stress management an example of thelatter. He argues that it is not necessarily more fair, by luckegalitarian lights, to only hold people responsible for the formerbehaviors than to simply refrain from holding people responsible fortheir choices (Cavallero 2011: 395).

Segall (2010), by contrast, accepts that luck egalitarians cannotavoid the abandonment objection by appeal to egalitarianconsiderations, but can do so if they appeal to moral considerationsunrelated to distributive justice—e.g., meeting people’sbasic needs. Voorhoeve (2019: 155) similarly adopts a pluralisticview, arguing that a luck egalitarian approach should be combined witha social egalitarian approach since the latter

specifies that one has reason to be averse to choice-basedinequalities that threaten people’s status as equal citizens andsocial cohesion.

Others address the question of harmful health behaviors by developingRawls’s (1982) concept of thesocial division ofresponsibility. According to Rawls (1982 [1999: 371]), society isresponsible for securing people’s basic liberties and providingeach with a fair share of opportunities and income and wealth, whileindividuals are responsible for setting goals and projects in light ofthe legitimate claims they may make on social institutions. Applyingthis concept to health inequalities, Kniess (2019: 115) argues thatpeople are responsible for the health outcomes of choices made underconditions of social justice, but not those outcomes due to choicesmade under conditions of social disadvantage. As Kniess puts it,

where there is no justice, there is no (substantive)responsibility…the disadvantaged in an unjust society aretherefore let off the hook, so to speak, no matter what they do ordon’t do to look after their health. (2019: 116)

Even if people’s choices to drink excessively, eat an unhealthydiet, or fail to exercise are voluntary, on this view, if such choicesare made under conditions of unjust social disadvantage, people arenot responsible for the downstream consequences. Daniels (2011)develops a similar Rawlsian view, but emphasizes that even underconditions of social justice, policymakers should be wary of holdingindividuals accountable for the costs of their health behaviors. Weall have an interest, Daniels argues, in having the freedom to makechoices regarding sport, sex, and diet without the fear of socialsanction when our choices turn out to be “bad” ones (seealso Fleck 2012).

Ben Davies and Julian Savulescu (2019) provide an alternative argumentfor holding individuals responsible for the health behaviors. Theyargue that where healthcare systems are grounded in solidarity, peoplehave obligations to fellow members of the system to protect theirhealth and may be held responsible for some or all of the costs oftreatment that result from a failure to do so. Solidarity, Davies andSavulescu (2019: 135) argue, is a two-way street, meaning that membersof a system founded in solidarity not only have claims on othermembers of the system, but also obligations to them. These obligationsinclude a duty not to imposeunreasonable costs on members ofthe system, with such costs being the result of refusals of“Golden Opportunities”, that is, refusals to makerealistically adoptable, health promoting behavioral changes, whichare performed under conditions conducive to responsible choice (Davies& Savulescu 2019: 139–140). Davies and Savulescu (2019, 141)caution however, that it is only permissible to hold peopleresponsible for refusals of Golden Opportunities if solidarity ispracticed in the broader social system, meaning that all people areheld responsible for failures of solidarity—e.g., including therich for tax avoidance.

In sum, although the claim that inequalities due to voluntary chosenhealth behaviors are not unjust is prima facie plausible, few arewilling to endorse it and/or its policy implications withoutsignificant qualification. Luck egalitarians either reject it byappealing to further egalitarian considerations or opt for apluralistic view that enables them to avoid its counter-intuitivepolicy implications. Similarly, those who adopt either Rawlsian orsolidaristic approaches hold that people are only responsible for theoutcomes of their voluntarily chosen health behaviors in the contextof a just society.

Others reject the idea that people are responsible for health outcomesdue to harmful health behaviors. Daniel Wikler (2004) offers asustained critique of the unmodified luck egalitarian view, pressingthe abandonment objection but also raising a number of practicalproblems regarding the view’s applications, including thedifficulty of identifying voluntary actions and the arbitrariness offinding fault with some choices but not others (see also Fleck 2012).He concludes that personal responsibility should only be employed inhealth policy as an ideal in health promotion campaigns to motivateand encourage people to take an active role in living healthylives.

Neil Levy (2019) similarly rejects the idea of personal responsibilityfor health by focusing on the greater prevalence of harmful healthbehaviors among people with low socioeconomic status. The explanationfor this disparity, Levy (2019: 106–107) argues, is that suchpeople, due to their circumstances, have reduced agential capacities,lower education, and make choices under the stressful conditions ofpoverty. For many, these challenges are significant enough to renderthem non-responsible for the behaviors that contribute to ill health.Since most people who are causally responsible for their ill healthare morally non-responsible in this way, Levy argues (2019: 109),health policy should not be designed on the premise that people areresponsible for their ill health. Instead, since the distribution ofagential capacities and the circumstances of choice is the result ofpublic policy and the actions of large corporations, it is theselatter actors who bear responsibility for the health outcomes inquestion (Levy 2019: 110).

Others are skeptical of this line of argument. Ben Schwan (2021)cautions that the mere fact that people’s choices are influencedby the social determinants of health does not mean that they are notresponsible for them—some social determinants of health are“responsibility-preserving”. Cavallero (2019) arguessimilarly that the health-related choices of people with lowsocio-economic status satisfy widely accepted criteria of responsiblechoice, namely, that they are made in the context of reasonablealternatives and are not coerced. He argues further that questioningthe autonomy and responsibility of people of low socioeconomic statusis incompatible with the liberal ideal that all competent adults aredeserving of equal respect and opens the door to paternalisticrestrictions of people’s liberty (Cavallero 2019). This does notimply, however, that society is notalso responsible for thedisparate health outcomes of low SES individuals. Cavallero (2019:378) agrees that the pattern Levy (2019) identifies is morallytroubling and argues that governments have an obligation to ensurethat people do

not face unequal health opportunities simply in virtue of theirsocioeconomic status of origin if those inequalities are remediablethrough reasonable public interventions.

Finally, others argue that the focus on personal responsibility indebates regarding priority setting and health promotion is misplacedor even fundamentally mistaken. Phoebe Friesen (2018: 56) makes astrong case that the behaviors policymakers wish to hold peopleresponsible for—e.g., excessive drinking, smoking, and pooreating habits—are stigmatized. She challenges proponents ofconsidering personal responsibility in health policy to either explaintheir focus on socially undesirable behaviors, or to extend theirarguments to include behaviors that contribute to ill health, areknown to be risky, and that are under people’scontrol—e.g., living in a city with high levels of airpollution, engaging in a dangerous sport, or spending too much time inthe sun (Friesen 2018: 56). Others worry that a focus on individualresponsibility may distract policymakers from the more urgent need toaddress the social determinants of health and may also stigmatizepeople who act “irresponsibly” (Voigt 2013; Goldberg2012). Since socio-economic conditions are the principal determinantsof health outcomes, these critics argue, such structural factors oughtto be the focus of public policy.

8. Justice and Global Health Inequalities

Discussions of justice and health inequality often focus oninequalities among members of the same polity. However, scholars havealso addressed the justice of international health disparities, which,depending on the countries of comparison, can be drastic. As we noteabove, life expectancy in low-income countries in 2016 was 62.7 years,compared to 80.8 years in high-income countries, a gap of 18.1 years(WHO 2020). These disparities are no doubt driven by the wide incomedifferences among these countries, and so questions regarding theirjustice are tightly connected to questions of global distributivejustice (see entries oninternational distributive justice andglobal justice). However, global health inequalities are also driven by war, climatechange, healthcare worker migration, and the funding decisions ofsponsors of medical research, among other factors. Positions regardingthe justice of global health disparities may therefore havefar-reaching implications for a diverse set of policy spheres.

Given the tight connection between global health justice and globaldistributive justice, it is no surprise that approaches to the formerpiggy-back on approaches to the latter. Briefly,cosmopolitans start from the premise that all humans aremoral equals and argue on this basis that high-income states haverobust distributive obligations to people regardless of theirnationality or relation to them. Some cosmopolitans defend asufficientarian position (Brock 2009), while others argue that globaljustice demands equality since national membership is a morallyarbitrary factor on the basis of which people should not bedisadvantaged (Caney 2005).Institutionalists do not rejectthe claim that all humans are moral equals but argue that robustdistributive obligations—as opposed to a duty ofassistance—are contingent on the existence of certain types ofinstitutions, whether a coercive legal system (Nagel 2005; Blake 2001)or institutions establishing substantial economic interdependence(Sangiovanni 2007; J. Cohen & Sabel 2006).

Turning to theories of global health justice, a number of scholarsdefend sufficientarian accounts, according to which all people areentitled to some minimum level of health or opportunity to be healthy.Sridhar Venkatapuram (2011: 224) defends a cosmopolitan account ofglobal health justice according to which all people have anentitlement to the capability to be healthy, secured at a thresholdsufficient to ensure their equal human dignity. Jennifer Prah Ruger(2018: 82) defends an institutionalist sufficientarian approach,“provincial globalism”, according to which states and thebroader global community have an obligation to ensure that all peopleenjoy a threshold level of central health capabilities. Others defendthe human right to health, understood as a right to “protectionagainst ‘standard threats’ to health” (Wolff 2012:27), or as a right to those things necessary for a basic minimum ofhealth and so for a minimally good life (Hassoun 2020; see also Powers& Faden 2006: 85).

Segall (2010) defends a cosmopolitan luck prioritarian account ofglobal health justice. National membership is a morally arbitraryfeature of one’s identity, Segall argues, and so disadvantagesin people’s opportunities for health that are due to nationalmembership should be addressed, with priority given to those who areworse off. While luck egalitarian or prioritarian positions oftenpermit deficits in health due to voluntary choices in the domesticcontext, Segall (2010) rejects appeals to national responsibility tojustify global health disparities on the grounds that not allresidents of a polity can be held responsible for national policies.Even in an ideal world of democratic countries operating in thecontext of a just global economic order, policy decisions will be madeon behalf of children and against the wishes of dissenters.

Hausman (2012) criticizes luck egalitarian and prioritarian accountson the grounds that they may imply policies that exacerbateinternational inequalities in income or opportunity. Since citizens ofsome low-income countries experience better health than citizens ofsome middle- and high-income countries, policies aimed at addressingthe poor health outcomes of the latter may exacerbate incomeinequalities among these countries. Luck egalitarian and prioritarianviews therefore face difficult questions regarding the prioritizationof health equality over equality of income or equality of opportunity.As an alternative to these accounts, Hausman (2012: 45) proposes arelational egalitarian account of global health justice, positing thatsome health inequalities across borders may be drastic enough to

render individuals in one nation vulnerable to domination by othernations and diminish their voice in international co-operation.

Although Hausman’s proposal is more of a sketch than an accountof global health justice, it faces the above-mentioned problem withdomestic relational egalitarian approaches, namely, identifying thehealth inequalities which in fact undermine equal relations. Forexample, when are the difference in life expectancy among citizens oftwo countries large enough to imply that they do not have equal statuswhen representatives negotiate a trade deal?