Logic of Belief Revision

In the logic of belief revision (belief change), a belief state (ordatabase) is represented by a set of sentences. The major operationsof change are those consisting in the introduction or removal of abelief-representing sentence. In both cases, changes affecting othersentences may be needed (for instance in order to retain consistency).Rationality postulates for such operations have been proposed, andrepresentation theorems have been obtained that characterize specifictypes of operations in terms of these postulates.

In the dominant theory of belief revision, the so-called AGM model,the set representing the belief state is assumed to be a logicallyclosed set of sentences (abelief set). One of most debatedtopics in belief revision theory is the recovery postulate, accordingto which all the original beliefs are regained if one of them is firstremoved and then reinserted. The recovery postulate holds in the AGMmodel but not in closely related models employing belief bases.Another much discussed topic is how repeated changes can be adequatelyrepresented. Several alternative models have been proposed that areintended to provide a more realistic account of belief change thanthat offered by the AGM model.

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Contraction

- 3. Revision

- 4. Possible world modelling

- 5. Belief bases

- 6. Other operations

- 6.1 Update

- 6.2 Consolidation

- 6.3 Semi-revision

- 6.4 Selective revision

- 6.5 Shielded contraction

- 6.6 Replacement

- 6.7 Merge

- 6.8 Multiple contraction and revision

- 6.9 Indeterministic belief change

- 6.10 Operations for an extended language

- 6.11 Changes in the strength of beliefs

- 6.12 Changes in norms and preferences

- 7. Iterated change

- 8. Alternative accounts

- Bibliography

- Academic Tools

- Other Internet Resources

- Related Entries

1. Introduction

1.1 History

Belief revision (belief change, belief dynamics) has been recognizedas a subject of its own since the middle of the 1980s. It grew out oftwo converging research traditions.

One of these emerged in computer science. Since the beginning ofcomputing, programmers have developed procedures by which databasescan be updated. The development of Artificial Intelligence inspiredcomputer scientists to construct more sophisticated models of databaseupdating. The truth maintenance systems developed by Jon Doyle (1979)were important in this development. One of the most significanttheoretical contributions was a 1983 paper by Ronald Fagin, JeffreyUllman and Moshe Vardi, in which they introduced the notion ofdatabase priorities.

The second of these two research traditions is philosophical. In awide sense, belief change has been a subject of philosophicalreflection since antiquity. In the twentieth century, philosophershave discussed the mechanisms by which scientific theories develop,and they have proposed criteria of rationality for revisions ofprobability assignments. Beginning in the 1970s, a more focuseddiscussion has taken place on the requirements of rational beliefchange. Two milestones can be pointed out. The first was a series ofstudies conducted by Isaac Levi in the 1970s (Levi 1977, 1980). Leviposed many of the problems that have since then been major concerns inthis field of research. He also provided much of the basic formalframework. William Harper’s (1977) work from the same period hasalso had a lasting influence.

The next milestone was the AGM model, so called after its threeoriginators, Carlos Alchourrón, Peter Gärdenfors, andDavid Makinson (1985). Alchourrón and Makinson had previouslycooperated in studies of changes in legal codes (Alchourrón andMakinson 1981, 1982). Gärdenfors’s early work was concernedwith the connections between belief change and conditional sentences(Gärdenfors 1978, 1981). With combined forces the three wrote apaper that provided a new, much more general and versatile formalframework for studies of belief change. (On the history of their jointwork, see Makinson 2003 and Gärdenfors 2011.) Since the paper waspublished in theJournal of Symbolic Logic in 1985, its majorconcepts and constructions have been the subject of significantelaboration and development. The AGM model and developments that havegrown out of it still form the core of belief revision theory.

1.2 The representation of beliefs and changes

In the AGM model and most other models of belief change, beliefs arerepresented by sentences in some formal language. Sentences do notcapture all aspects of belief, but they are the best general-purposerepresentation that is presently available.

The beliefs held by an agent are represented by a set of suchbelief-representing sentences. It is usually assumed that this set isclosed under logical consequence, i.e., every sentence that followslogically from this set is already in the set. This is clearly anunrealistic idealization, since it means that the agent is taken to be“logically omniscient”, i.e. a perfect logical reasoner.However, it is a useful idealization since it simplifies the logicaltreatment; indeed, it seems difficult to obtain an interesting formaltreatment without it. In logic, logically closed sets are called“theories”. In formal epistemology they are also called“corpora”, “knowledge sets”, or (morecommonly) “belief sets”.

Isaac Levi (1991) has clarified the nature of this idealization bypointing out that a belief set consists of the sentences that someoneiscommitted tobelieve, not those that she actuallybelieves in. According to Levi, we are doxastically committed tobelieve in all the logical consequences of our beliefs, but typicallyour performance does not live up to this commitment. The belief set isthe set of the agent’s epistemic commitments, and thereforelarger than the set of her actually held beliefs.

In the AGM framework, there are three types of belief change. Incontraction, a specified sentence \(p\) is removed, i.e., abelief set \(K\) is superseded by another belief set \(K\div p\) thatis a subset of \(K\) not containing \(p\). Inexpansion asentence \(p\) is added to \(K\), and nothing is removed, i.e. \(K\)is replaced by a set \(K+p\) that is the smallest logically closed setthat contains both \(K\) and \(p\). Inrevision a sentence\(p\) is added to \(K\), and at the same time other sentences areremoved if this is needed to ensure that the resulting belief set \(K*p\) is consistent.

It is important to note the specific character of these models. Theyareinput-assimilating. This means that the object of change,the belief set, is exposed to an input, and is changed as a result ofthis. No explicit representation of time is included. Instead, thecharacteristic mathematical constituent is a function that, to eachpair of a belief set and an input, assigns a new belief set.

1.3 Formal preliminaries

The belief-representing sentences form a language. (As is usual inlogic, the language is identified with the set of all sentences itcontains.) Sentences, i.e. elements of this language, will berepresented by lowercase letters \((p, q\ldots)\) and sets ofsentences by capital letters. This language contains the usualtruth-functional connectives: negation \((\neg)\), conjunction\((\amp)\), disjunction \((\vee)\), implication \((\rightarrow)\), andequivalence (\(\leftrightarrow\)). \(\smbot\) denotes an arbitrarycontradiction (“falsum”), and \(\smtop\) an arbitrarytautology.

To express the logic, a Tarskianconsequence operator will beused. Intuitively speaking, for any set \(A\) of sentences, \(\Cn(A)\)is the set of logical consequences of \(A\). More formally, aconsequence operation on a given language is a function \(\Cn\) fromsets of sentences to sets of sentences. It satisfies the followingthree conditions:

Inclusion:

\(A\subseteq \Cn(A)\)

Monotony:

If \(A\subseteq B\), then \(\Cn(A) \subseteq \Cn(B)\)

Iteration:

\(\Cn(A) = \Cn(\Cn(A))\)

\(\Cn\) is assumed to be supraclassical, i.e. if \(p\) can be derivedfrom \(A\) by classical truth-functional logic, then \(p \in \Cn(A)\).\(A\) is a belief set if and only if \(A = \Cn(A)\). In what follows,\(K\) will denote a belief set. \(X \vdash p\) is an alternativenotation for \(p \in \Cn(X)\), and \(X \not\vdash p\) for \(p \not\in\Cn(X)\). \(\Cn(\varnothing)\) is the set of tautologies.

The expansion of \(K\) by a sentence \(p\), i.e. the operation thatjust adds \(p\) and removes nothing, is denoted \(K+p\) and defined asfollows: \(K+p = \Cn(K\cup \{p\})\).

2. Contraction

2.1 Partial meet contraction

The outcome of contracting \(K\) by \(p\) should be a subset of \(K\)that does not imply \(p\), but from which no elements of \(K\) havebeen unnecessarily removed. Therefore, it is of interest to considerthe inclusion-maximal subsets of \(K\) that do not imply \(p\).

For any set \(A\) and sentence \(p\) theremainder set\(A\bot p\) (“\(A\) remainder \(p\)”) is the set ofinclusion-maximal subsets of \(A\) that do not imply \(p\). In otherwords, a set \(B\) is an element of \(A\bot p\) if and only if it itis a subset of \(A\) that does not imply \(p\), and there is no set\(B'\) not implying \(p\) such that \(B\subset B'\subseteq A\). Theelements of \(A\bot p\) are called “remainders”.

If the operation of contraction uncompromisingly minimizes informationloss, then \(K\div p\) will be one of the remainders. However, thisconstruction can be shown to have implausible properties. A morereasonable recipe for contraction is to let \(K\div p\) be theintersection of some of the remainders. This ispartial meetcontraction, the major innovation in the classic 1985 paper byCarlos Alchourrón, Peter Gärdenfors and David Makinson. Anoperation of partial meet contraction employs aselectionfunction that selects the “best” elements of \(K\botp\). More precisely, a selection function for \(K\) is a function\(\gamma\) such that if \(K\bot p\) is non-empty, then \(\gamma(K\botp)\) is a non-empty subset of \(K\bot p\). In the limiting case when\(K\bot p\) is empty, then \(\gamma(K\bot p)\) is defined to be equalto \(\{K\}\).

The outcome of the partial meet contraction is equal to theintersection of the set of selected elements of \(K\bot p\), i.e.\(K\div p = \bigcap \gamma(K\bot p)\).

The limiting case when for all sentences \(p\), \(\gamma(K\bot p)\)has exactly one element is calledmaxichoice contraction. Theother limiting case in which \(\gamma(K\bot p) = K\bot p\) whenever\(K\bot p\) is non-empty is calledfull meet contraction.Both limiting cases are technically useful, but they also both havehighly unrealistic properties.

Partial meet contraction of a belief set satisfies six postulates thatare called thebasic Gärdenfors postulates (or basic AGMpostulates). To begin with, when a belief set \(K\) is contracted by asentence \(p\), the outcome should be logically closed.

Closure:

\(K\div p = \Cn(K\div p)\)

Contraction should be successful, i.e., \(K\div p\) should not imply\(p\) (or not contain \(p\), which is the same thing if Closure issatisfied). However, it would be too much to require that \(p \not\in\Cn(K\div p)\) for all sentences \(p\), since it cannot hold if \(p\)is a tautology. The success postulate has to be conditional on \(p\)not being logically true.

Success:

If \(p \not\in \Cn(\varnothing)\), then \(p \not\in \Cn(K\div p)\).

The Success postulate has been put in doubt since there may besentences other than tautologies that an epistemic agent may refuse towithdraw. (On operations that do not satisfy Success, see Section6.5.)

The contracted set is assumed to be a subset of the original one:

Inclusion:

\(K\div p \subseteq K\)

Inclusion is usually considered to be a constitutive property ofcontraction. However, it has also been questioned with the argumentthat when the epistemic agent ceases to believe in \(p\), then this isusually because she receives some new information that contradicts\(p\). Arguably, that information should be included in \(K\div p\).

If the sentence to be contracted is not included in the originalbelief set, then contraction by that sentence involves no change atall. Such contractions are idle (vacuous) operations, and they shouldleave the original set unchanged.

Vacuity:

If \(p \not\in \Cn(K)\), then \(K\div p = K\).

Logically equivalent sentences should be treated alike incontraction:

Extensionality:

If \(p\leftrightarrow q \in \Cn(\varnothing)\), then \(K\div p = K\divq\).

Extensionality guarantees that the logic of contraction is extensionalin the sense of allowing logically equivalent sentences to be freelysubstituted for each other.

Belief contraction should not only be successful, it should also beminimal in the sense of leading to the loss of as fewprevious beliefs as possible. The epistemic agent should give upbeliefs only when forced to do so, and should then give up as few ofthem as possible. This is ensured by the following postulate:

Recovery:

\(K \subseteq (K\div p)+p\)

According to Recovery, so much is retained after \(p\) has beenremoved that everything will be recovered by reinclusion (throughexpansion) of \(p\).

One of the central results about the AGM model is a representationtheorem for partial meet contraction. According to this theorem, anoperation \(\div\) is a partial meet contraction for a belief set\(K\) if and only if it satisfies the six above-mentioned postulates,namely Closure, Success, Inclusion, Vacuity, Extensionality, andRecovery.

A selection function for a belief set \(K\) should, for all sentences\(p\), select those elements of \(K\bot p\) that are“best”, or most worth retaining. However, the definitionof a selection function is very general, and allows for quitedisorderly selection patterns. An orderly selection function shouldalways choose the best element(s) of the remainder set according tosome well-behaved preference relation. A selection function \(\gamma\)for a belief set \(K\) isrelational if and only if there isa binary relation \(\mathbf{R}\) such that for all sentences \(p\), if\(K\bot p\) is non-empty, then \(\gamma(K\bot p) = \{B \in K\bot p\mid C\mathbf{R}B\) for all \(C \in K\bot p\}\). Furthermore, if\(\mathbf{R}\) is transitive (i.e., it satisfies: If \(A\mathbf{R}B\)and \(B\mathbf{R}C\), then \(A\mathbf{R}C)\), then \(\gamma\) and thepartial meet contraction that it gives rise to aretransitivelyrelational.

In order to characterize transitively relational partial meetcontraction, postulates are needed that refer to contraction byconjunctions.

In order to give up a conjunction \(p \amp q\), the agent mustrelinquish either her belief in \(p\) or her belief in \(q\) (orboth). Suppose that contracting by \(p \amp q\) leads to loss of thebelief in \(p\), i.e., that \(p \not\in K\div(p \amp q)\). It can beexpected that in this case contraction by \(p \amp q\) should lead tothe loss of all beliefs that would have been lost in order to contractby \(p\). Another way to express this is that everything that isretained in \(K\div(p \amp q)\) is also retained in \(K\div p\):

Conjunctive inclusion:

If \(p \not\in K\div(p \amp q)\), then \(K\div(p \amp q) \subseteqK\div p\).

Another fairly reasonable principle for contraction by conjunctions isthat whatever can withstand both contraction by \(p\) and contractionby \(q\) can also withstand contraction by \(p \amp q\). In otherwords, whatever is an element of both \(K\div p\) and \(K\div q\) isalso an element of \(K\div(p \amp q)\).

Conjunctive overlap:

\((K\div p) \cap (K\div q) \subseteq K\div(p \amp q)\)

Conjunctive overlap and Conjunctive inclusion are commonly calledGärdenfors’s supplementary postulates for beliefcontraction. An operation \(\div\) for \(K\) is a transitivelyrelational partial meet contraction if and only if it satisfies thesix basic postulates and in addition both Conjunctive overlap andConjunctive inclusion.

2.2 Entrenchment-based contraction

When forced to give up previous beliefs, the epistemic agent shouldgive up beliefs that have as little explanatory power and overallinformational value as possible. As an example of this, in the choicebetween giving up beliefs in natural laws and beliefs in singlefactual statements, beliefs in the natural laws, that have much higherexplanatory power, should in general be retained. This was the basicidea behind Peter Gärdenfors’s proposal that contraction ofbeliefs should be ruled by a binary relation,epistemicentrenchment. (Gärdenfors 1988, Gärdenfors and Makinson1988) To say of two elements \(p\) and \(q\) of the belief set that“\(q\) is more entrenched than \(p\)” means that \(q\) ismore useful in inquiry or deliberation, or has more “epistemicvalue” than \(p\). In belief contraction, the beliefs with thelowest entrenchment should be the ones that are most readily givenup.

The following symbols will be used for epistemic entrenchment:

\(p\le q : p\) is at most as entrenched as \(q\).

\(p\lt q : p\) is less entrenched than \(q\). \(((p\le q) \amp\neg(q\le p)))\)

\(p\equiv q : p\) and \(q\) are equally entrenched. \(((p\le q)\amp(q\le p))\)

Gärdenfors has proposed the following five postulates forepistemic entrenchment. They are often referred to as the standardpostulates for entrenchment:

Transitivity:

If \(p\le q\) and \(q\le r\), then \(p\le r\).

Dominance:

If \(p \vdash q\), then \(p\le q\).

Conjunctiveness:

Either \(p\le(p \amp q)\) or \(q\le(p \amp q)\).

Minimality:

If the belief set \(K\) is consistent, then \(p \not\in K\) if andonly if \(p\le q\) for all \(q\).

Maximality:

If \(q\le p\) for all \(q\), then \(p \in \Cn(\varnothing)\).

It follows from the first three of these postulates that anentrenchment relation satisfies connectivity (completeness), i.e. itholds for all \(p\) and \(q\) that either \(p\le q\) or \(q\lep\).

An entrenchment relation \(\le\) gives rise to an operation \(\div\)of entrenchment-based contraction according to the followingdefinition:

\(q \in K\div p\) if and only if \(q \in K\) and either \(p \lt(p \veeq)\) or \(p \in \Cn(\varnothing)\).

Entrenchment-based contraction has been shown to coincide exactly withtransitively relational partial meet contraction. For a thoroughdiscussion and more results on entrenchment relations, see Rott2001.

2.3 Recovery and its avoidance

Recovery is the most debated postulate of belief change. It is easy tofind examples that seem to validate Recovery. A person who first losesand then regains her belief that she has a dollar in her pocket seemsto return to her previous state of belief. However, other examples canalso be presented, in which Recovery yields implausible results. Thefollowing are two of the examples that have been offered to show thatRecovery does not hold in general:

I have read in a book about Cleopatra that she had both a son and adaughter. My set of beliefs therefore contains both \(p\) and \(q\),where \(p\) denotes that Cleopatra had a son and \(q\) that she had adaughter. I then learn from a knowledgeable friend that the book is infact a historical novel. After that I contract \(p\vee q\) from my setof beliefs, i.e., I do not any longer believe that Cleopatra had achild. Soon after that, however, I learn from a reliable source thatCleopatra had a child. It seems perfectly reasonable for me to thenadd \(p\vee q\) to my set of beliefs without also reintroducing either\(p\) or \(q\). This contradicts Recovery.

I previously entertained the two beliefs “George is acriminal” \((p)\) and “George is a mass murderer”\((q)\). When I received information that induced me to give up thefirst of these beliefs \((p)\), the second \((q)\) had to go as well(since \(p\) would otherwise follow from \(q)\).

I then received new information that made me accept the belief“George is a shoplifter” \((r)\). The resulting new beliefset is the expansion of \(K\div p\) by \(r\), \((K\div p)+r.\) Since\(p\) follows from \(r\), \((K\div p)+p\) is a subset of \((K\divp)+r\). By recovery, \((K\div p)+p\) includes \(q\), from whichfollows that \((K\div p)+r\) includes \(q\).

Thus, since I previously believed George to be a mass murderer, itfollows from Recovery that I cannot after that believe him to be ashoplifter without believing him to be a mass murderer.

Due to the problematic nature of this postulate, it should beinteresting to find intuitively less controversial postulates thatprevent unnecessary losses in contraction. The following is an attemptto do that:

Core-retainment:

If \(q \in K\) and \(q \not\in K\div p\), then there is a belief set\(K'\) such that \(K' \subseteq K\) and that \(p \not\in K'\) but \(p\in K'+q\).

Core-retainment requires of an excluded sentence \(q\) that it in someway contributes to the fact that \(K\) implies \(p\). It gives theimpression of being weaker and more plausible than Recovery. However,it has been shown that if an operator \(\div\) for a belief set \(K\)satisfies Core-retainment, then it satisfies Recovery.

Attempts have been made to construct operations of contraction onbelief sets that do not satisfy Recovery. Arguably, the most plausibleof these constructions is the operation ofsevere withdrawalthat has been thoroughly investigated by Hans Rott and MauricePagnucco (2000). It can be constructed from an operation of epistemicentrenchment by modifying the definition as follows:

\(q \in K\div p\) if and only if \(q \in K\) and either \(p \lt q\) or\(p \in \Cn(\varnothing)\).

Severe withdrawal has interesting features, but it also has thefollowing property:

Expulsiveness:

If \(p \not\in \Cn(\varnothing)\) and \(q \not\in \Cn(\varnothing)\)then either \(p \not\in K\div q\) or \(q \not\in K\div p\).

This is a highly implausible property of belief contraction, since itdoes not allow unrelated beliefs to be undisturbed by eachother’s contraction. Consider a scholar who believes that hercar is parked in front of the house. She also believes thatShakespeare wrote the Tempest. It should be possible for her to giveup the first of these beliefs while retaining the second. She shouldalso be able to give up the second without giving up the first.Expulsiveness does not allow this. The construction of a plausibleoperation of contraction for belief sets that does not satisfyRecovery is still an open issue.

3. Revision

The two major tasks of an operation \(*\) of revision are (1) to addthe new belief \(p\) to the belief set \(K\), and (2) to ensure thatthe resulting belief set \(K* p\) is consistent (unless \(p\) isinconsistent). The first task can be accomplished by expansion by\(p\). The second can be accomplished by prior contraction by itsnegation \(\neg p\). If a belief set does not imply \(\neg p\), then\(p\) can be added to it without loss of consistency. This compositionof suboperations gives rise to the following definition of revision(Gärdenfors 1981, Levi 1977):

Levi identity:

\(K* p = (K\div \neg p)+p\).

If \(\div\) is a partial meet contraction, then the operation \(*\)that is defined in this way is apartial meet revision. Thisis the standard construction of revision in the AGM model.

Partial meet revision has been axiomatically characterized. Anoperation \(*\) is a partial meet revision if and only if it satisfiesthe following six postulates:

Closure:

\(K* p = \Cn(K* p)\)

Success:

\(p \in K* p\)

Inclusion:

\(K* p \subseteq K+p\)

Vacuity:

If \(\neg p \not\in K\), then \(K* p = K+p\).

Consistency:

\(K* p\) is consistent if \(p\) is consistent.

Extensionality:

If \((p \leftrightarrow q) \in \Cn(\varnothing)\), then \(K* p = K*q\).

These six postulates are commonly called thebasic Gärdenforspostulates for revision. The most controversial of them isSuccess. It implies that in response to an inconsistent inputsentence, the epistemic agent will acquire an inconsistent belief set,according to which she holds all sentences to be true. Even forconsistent input sentences, Success is contestable. It is notimplausible for an epistemic agent to consider some statements to beso implausible that nothing can make her believe in them. For beliefrevision models that do not satisfy Success, see section 6.3. and6.4.

The following two supplementary postulates are parts of the standardrepertoire:

Superexpansion:

\(K* (p \amp q) \subseteq(K* p)+q\)

Subexpansion:

If \(\neg q \not\in \Cn(K* p)\), then \((K* p)+q \subseteq K* (p \ampq)\).

These postulates are closely related to the supplementary postulatesfor contraction. Let \(*\) be the partial meet revision defined fromthe partial meet contraction \(\div\) via the Levi identity. Then\(*\) satisfies superexpansion if and only if \(\div\) satisfiesconjunctive overlap. Furthermore, \(*\) satisfies subexpansion if andonly if \(\div\) satisfies conjunctive inclusion.

The following postulate was introduced by Hans Rott:

Disjunctive factoring:

\(K* (p\vee q) \) is equal to one of \(K* p\), \(K* q\), and \(K*p\cap K* q\).

Rott showed that in the presence of the six basic AGM postulates, thetwo supplementary AGM postulates, Superexpansion and Subexpansion,both hold if and only if Disjunctive factoring holds.

4. Possible world modelling

Alternative models of belief states can be constructed out of sets ofpossible worlds (Grove 1988). In logical parlance, by apossibleworld is meant a maximal consistent subset of the language. By aproposition is meant a set of possible worlds. There is aone-to-one correspondence between propositions and belief sets. Eachbelief set can be represented by the proposition (set of possibleworlds) that consists of those possible worlds that contain the beliefset in question.

For any set \(A\) of sentences, let \([A]\) denote the set of possibleworlds that contain \(A\) as a subset, and similarly for any sentence\(p\) let \([p]\) be the set of possible worlds that contain \(p\) asan element. If \(A\) is inconsistent, then \([A] = \varnothing\).Otherwise, \([A]\) is a non-empty set of possible worlds. (It isassumed that \(\bigcap \varnothing\) is equal to the whole language.)If \(K\) is a belief set, then \(\bigcap[K] = K\).

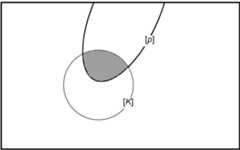

The propositional account provides an intuitively clear picture ofsome aspects of belief change. It is convenient to use a geometricalsurface to represent the set of possible worlds. InDiagram1, every point on the rectangle’s surface represents apossible world. The circle marked \([K]\) represents those possibleworlds in which all sentences in \(K\) are true, i.e., the set \([K]\)of possible worlds. The area marked \([p]\) represents those possibleworlds in which the sentence \(p\) is true.

Diagram 1. Revision of \(K\) by\(p\).

InDiagram 1, \([K]\) and \([p]\) have a non-emptyintersection, which means that \(K\) is compatible with \(p\). Therevision of \(K\) by \(p\) is therefore not belief-contravening. Itsoutcome is obtained by giving up those elements of \([K]\) that areincompatible with \(p\). In other words, the result of revising\([K]\) by \([p]\) should be equal to \([K]\cap[p]\).

If \([K]\) and \([p]\) do not intersect, then the outcome of therevision must be sought outside of \([K]\), but it should neverthelessbe a subset of \([p]\). In general:

The outcome of revising \([K]\) by \([p]\) is a subset of \([p]\) thatis

- non-empty if \([p]\) is non-empty

- equal to \([K]\cap[p]\) if \([K]\cap[p]\) is non-empty

This simple rule for revision can be shown tocorrespond exactlyto partial meet revision.

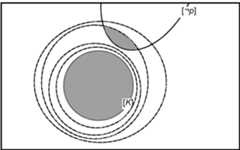

The revised belief state should not differ more from the originalbelief state \([K]\) than what is motivated by \([p]\). This can beachieved by requiring that the outcome of revising \([K]\) by \([p]\)consists of those elements of \([p]\) that are as close as possible to\([K]\). For that purpose, \([K]\) can be thought of as surrounded bya system of concentric spheres (just as in David Lewis’s accountof counterfactual conditionals). Each sphere represents a degree ofcloseness or similarity to \([K]\).

In this model, the outcome of revising \([K]\) by \([p]\) should bethe intersection of \([p]\) with the narrowest sphere around \([K]\)that has a non-empty intersection with \([p]\), as inDiagram2. This construction was invented by Adam Grove (1988), who alsoproved that such sphere-based revisioncorresponds exactly totransitively relational partial meet revision. It follows that italso corresponds exactly to entrenchment-based revision.

Diagram 2. Sphere-based revision of\(K\) by \(p\).

Possible world models can also be used for contraction. Incontraction, a restriction on what worlds are “possible”(compatible with the agent’s beliefs) is removed. Thus, the setof possibilities is enlarged, so that the contraction of \([K]\) by\([p]\) will result in a superset of \([K]\). Furthermore, the newpossibilities should be worlds in which \(p\) does not hold, i.e.,they should be worlds in which \(\neg p\) holds. In the limiting casewhen \([K]\) and \([\neg p]\) have a non-empty intersection, noenlargement of \([K]\) is necessary to make \(\neg p\) possible, andthe original belief state will therefore be unchanged. In summary,contraction should be performed according to the following rule:

The outcome of contracting \([K]\) by \([p]\) is the union of \([K]\)and a subset of \([\neg p]\) that is

- non-empty if \([\neg p]\) is non-empty

- equal to \([K]\cap[\neg p]\) if \([K]\cap[\neg p]\) isnon-empty

Belief-contravening contraction is illustrated inDiagram 3.Contraction performed according to this rule can be shown tocorrespond exactly to partial meet contraction. Furthermore,the special case when the whole of \([\neg p]\) is added to \([K]\)corresponds exactly to full meet contraction. The otherextreme case, when only one element of \([\neg p]\) (a“point” on the surface) is added to \([K]\)corresponds exactly to maxichoice contraction. Thus, inmaxichoice contraction by \(p\) only one possible way in which \(p\)can be false \((\neg p\) can be true) is added.

Diagram 3. Contraction of \(K\) by\(p\).

Grove’s sphere systems can also be used for contraction. Insphere-based contraction by \(p\), those elements of \([\neg p]\) areadded that belong to the closest sphere around \([K]\) that has anon-empty intersection with \([\neg p]\). The procedure is shown inDiagram 4. Sphere-based contractioncorresponds exactlyto transitively relational partial meet contraction.

Diagram 4. Sphere-based contraction of\(K\) by \(p\).

5. Belief bases

5.1 Increased expressive power

In the approaches discussed above, all beliefs in the belief set aretreated equally in the sense that they are all taken seriously asbeliefs in their own right. However, due to logical closure the beliefset contains many elements that are not really worth to be takenseriously. Hence, suppose that the belief set contains the sentence\(p\), “Shakespeare wrote Hamlet”. Due to logical closureit then also contains the sentence \(p \vee q\), “EitherShakespeare wrote Hamlet or Charles Dickens wrote Hamlet”. Thelatter sentence is a “mere logical consequence” thatshould have no standing of its own.

Belief bases have been introduced to capture this feature of thestructure of human beliefs. A belief base is a set of sentences thatis not (except as a limiting case) closed under logical consequence.Its elements represent beliefs that are held independently of anyother belief or set of beliefs. Those elements of the belief set thatare not in the belief base are “merely derived”, i.e.,they have no independent standing. In this way, models employingbelief bases can be said to achieve a somewhat higher degree ofaffinity to natural-language doxastic reasoning than what seems to beachievable in models such as AGM that use belief sets asrepresentations of belief sets. (A still higher degree of affinity tonatural language can be obtained in models employing hyperintensionallogic; see Berto 2019.)

In belief base models, changes are performed on the belief base, whichis not logically closed. The underlying intuition is that the merelyderived beliefs are not worth retaining for their own sake. If one ofthem loses the support that it had in basic beliefs, then it will beautomatically discarded.

For every belief base \(A\), there is a belief set \(\Cn(A)\) thatrepresents the beliefs held according to \(A\). On the other hand, oneand the same belief set can be represented by different belief bases.In this sense, belief bases have more expressive power than beliefsets. As an example, the two belief bases \(\{p, q\}\) and \(\{p, p\leftrightarrow q\}\) have the same logical closure. They arethereforestatically equivalent, in the sense of representingthe same beliefs. On the other hand, the following example shows thatthey are notdynamically equivalent in the sense of behavingin the same way under operations of change. They can be taken torepresent different ways of holding the same beliefs.

Let \(p\) denote that the Liberal Party will support the proposal tosubsidize the steel industry, and let \(q\) denote that Ms. Smith, whois a liberal MP, will vote in favour of that proposal.

Abe has the basic beliefs \(p\) and \(q\), whereas Bob has the basicbeliefs \(p\) and \(p \leftrightarrow q.\) Thus, their beliefs (on thebelief set level) with respect to \(p\) and \(q\) are the same.

Both Abe and Bob receive and accept the information that \(p\) iswrong, and they both revise their belief states to include the newbelief that \(\neg p\). After that, Abe has the basic beliefs \(\negp\) and \(q\), whereas Bob has the basic beliefs \(\neg p\) and \(p\leftrightarrow q\). Now, their belief sets are no longer the same.Abe believes that \(q\) whereas Bob believes that \(\neg q\).

(In belief set models, cases like these are taken care of by assumingthat although Abe’s and Bob’s belief states arerepresented by the same belief set, this belief set is associated withdifferent selection mechanisms in the two cases. Abe has a selectionmechanism that gives priority to \(q\) over \(p \leftrightarrow q\),whereas Bob’s selection mechanism has the oppositepriorities.)

There is only one inconsistent belief set (logically closedinconsistent set), namely the whole language. On the other hand thereare, in any non-trivial logic, many different inconsistent beliefbases. Therefore, belief bases make it possible to distinguish betweendifferent inconsistent belief states.

In belief revision theory it has mostly been taken for granted thatbelief sets correspond to a coherentist epistemology, whereas beliefbases represent foundationalism. However, the logical relationshipsamong the elements of a logically closed set do not adequatelyrepresent epistemic coherence. Although coherentists typically claimthatall beliefs contribute to the justification of otherbeliefs, they hardly mean this to apply to merely derived beliefs suchas “either Paris or Rome is the capital of France”, thatone believes only because one believes Paris to be the capital ofFrance. Therefore, the distinction between operations on belief basesand operations on belief sets should not be equated with that betweenfoundationalism and coherentism.

5.2 Belief base contraction

Partial meet contraction, as defined in Section 2.1, is equallyapplicable to belief bases. Note that \(A\bot p\) is the set ofmaximal subsets of \(A\) that do not imply \(p\); it is not sufficientthat they do not contain \(p\). Hence

\[\{p, p \amp q, p \vee q, p \leftrightarrow q\} \bot p = \{\{p \vee q\}, \{p \leftrightarrow q\}\}.\]Most of the basic postulates for partial meet contraction on beliefsets hold for belief bases as well. However, Recovery does not holdfor partial meet contraction of belief bases. This can be seen fromthe following example (that is adopted from Isaac Levi (2004) who usedit for other purposes:

Let the belief set \(K\) include both a belief that the coin wastossed \((c)\) and a belief that it landed heads \((h)\). Theepistemic agent wishes to consider whether, on the supposition thatthe coin had been tossed, it would have landed heads. In order to dothat, it would seem reasonable to remove \(c\) from the belief set andthen reinsert it, i.e. to perform the series of operations \(K\divc+c\).

(1) If partial meet contraction is performed directly on the beliefset, then it follows from Recovery that \(h \in K\div c+c\), i.e.\(h\) comes back with \(c\). This is contrary to reasonableintuitions.

(2) If partial meet contraction is instead performed on a belief basefor \(K\), then recovery can be avoided. Let the belief base be\(\{p_1 ,\ldots ,p_n, c, h\}\), where the background beliefs \(p_1,\ldots ,p_n\) are unrelated to \(c\) and \(h\), whereas \(h\)logically implies \(c\). Then \(K = \Cn(\{p_1 ,\ldots ,p_n, c, h\})\).Since \(h\) implies \(c\), it will have to go when \(c\) is removed,so that \(K\div c = \Cn(\{p_1 ,\ldots ,p_n\})\). When \(c\) isreinserted, the outcome is \((K\div c)+c = \Cn(\{p_1 ,\ldots ,p_n,c\})\) that does not contain \(h\), as desired.

The following representation theorem has been obtained for partialmeet contraction on belief bases (Hansson 1999). An operation \(\div\)is a partial meet contraction for a set \(A\) if and only if itsatisfies the following four postulates:

Success:

If \(p \not\in \Cn(\varnothing)\), then \(p \not\in \Cn(A\divp)\).

Inclusion:

\(A\div p \subseteq A\)

Relevance:

If \(q \in A\) and \(q \not\in A\div p\), then there is a set \(A'\)such that \(A\div p \subseteq A' \subseteq A\) and that \(p \not\in\Cn(A')\) but \(p \in \Cn(A'\cup \{q\})\).

Uniformity:

If it holds for all subsets \(A'\) of \(A\) that \(p \in \Cn(A')\) ifand only if \(q \in \Cn(A')\), then \(A\div p = A\div q\).

The Relevance postulate has much the same function as Recovery has forbelief sets, namely to prevent unnecessary losses of beliefs.

An alternative approach to contraction of belief bases has beenproposed under the namekernel contraction. For any sentence\(p\), a \(p\)-kernel is a minimal \(p\)-implying set, i.e. a set thatimplies \(p\) but has no proper subset that implies \(p\). Acontraction operation \(\div\) can be based on the simple principlethat no \(p\)-kernel should be included in \(A\div p\). This can beobtained with an incision function, a function that selects at leastone element from each \(p\)-kernel for removal. An operation thatremoves exactly those elements that are selected for removal by anincision function is called a kernel contraction. It turns out thatall partial meet contractions on belief bases are kernel contractions,but some kernel contractions are not partial meet contractions. Inother words, kernel contraction is a generalization of partial meetcontraction.

5.3 Belief base revision

The operation of expansion for belief sets, \(K+p = \Cn(K\cup\{p\})\), was constructed to ensure that the outcome is logicallyclosed. This is not desirable for belief bases, and thereforeexpansion on belief bases must be different from expansion on beliefsets. For any belief base \(A\) and sentence \(p,\) \(A +' p\), the(non-closing)expansion of \(A\) by \(p\), is theset \(A\cup \{p\}\).

Just like the corresponding operations for belief sets, revisionoperations for belief bases can be constructed out of twosuboperations: expansion by \(p\) and contraction by \(\neg p\).According to the Levi identity, \((A* p = (A\div \neg p) +' p)\), thecontractive suboperation should take place first. Alternatively, thetwo suboperations may take place in reverse order, \(A* p = (A+'p)\div \neg p\). This latter possibility does not exist for belief sets.If \(K\cup \{p\}\) is inconsistent, then \(K+p\) is always the same,namely identical to the whole language, independently of the identityof \(K\) and of \(p\), so that all distinctions are lost. For beliefbases, this limitation is not present, and thus there are two distinctways to obtain revision from contraction and expansion:

Internal revision:

\(A * p = (A \div \neg p) +' p\)

External revision:

\(A * p = (A +' p) \div \neg p\)

Intuitively, external revision by \(p\) is revision with anintermediate inconsistent state in which both \(p\) and\(\neg p\) are believed, whereas internal revision has anintermediate non-committed state in which neither \(p\) nor\(\neg p\) is believed. External and internal revision differ in theirlogical properties, and neither of them can be subsumed under theother.

5.4 Connections between belief bases and belief sets

A contraction on a belief base gives rise to a contraction on itscorresponding belief set. Let \(A\) be a belief base and \(K =\Cn(A)\) its corresponding belief set. Furthermore, let \(-\) be acontraction on \(A\). It gives rise to an operation \(\div\) ofbase-generated contraction on \(K\), such that for allsentences \(p: K\div p = \Cn(A-p)\). Base-generated contraction hasbeen axiomatically characterized. An operation \(\div\) on aconsistent belief set \(K\) is generated by an operation of partialmeet contraction for some finite base for \(K\) if and only if itsatisfies the following eight postulates:

Closure:

\(K\div p = \Cn(K\div p)\)

Success:

If \(p \not\in \Cn(\varnothing)\), then \(p \not\in \Cn(K\divp)\).

Inclusion:

\(K\div p \subseteq K\)

Vacuity:

If \(p \not\in \Cn(K)\), then \(K\div p = K\).

Extensionality:

If \(p\leftrightarrow q \in \Cn(\varnothing)\), then \(K\div p = K\divq\).

Finitude:

There is a finite set \(X\) such that for every sentence \(p\),\(K\div p = \Cn(X')\) for some \(X' \subseteq X\).

Symmetry:

If it holds for all \(r\) that \(K\div r \vdash p\) if and only if\(K\div r \vdash q\), then \(K\div p = K\div q\).

Conservativity:

If \(K\div q\) is not a subset of \(K\div p\), then there is some\(r\) such that \(K\div p \subseteq K\div r \not\vdash p\) and \(K\divr \cup K\div q \vdash p\).

Operations of revision on a belief set can be base-generated in thesame sense as operations of contraction.

6. Other operations

The AGM framework has been extended in many ways. Some of theseextensions have introduced new types of operations in addition to thethree standard types in AGM, namely contraction, expansion, andrevision.

6.1 Update

There are two types of reasons why the epistemic agent may wish to addnew information to the belief set. One is that she has received newinformation about the world, the other that the world has changed. Itis common to reserve the term “revision” for the first ofthese types, and use the term “updating” for the second.The logic of updating differs from that of revision. This can be seenfrom the following example:

To begin with, the agent knows that there is either a book on thetable \((p)\) or a magazine on the table \((q)\), but not both.

Case 1: The agent is told that there is a book on the table. Sheconcludes that there is no magazine on the table. This isrevision.

Case 2: The agent is told that after the first information was given,a book has been put on the table. In this case she should not concludethat there is no magazine on the table. This is updating.

One useful approach to updating is to assign time indices to thesentences, as proposed by Katsuno and Mendelzon (1992). Then thebelief set will not consist of sentences \(p\) but of pairs \(\langlep,t_1\rangle\) of a sentence \(p\) and a point in time \(t_1\),signifying that \(p\) holds at \(t_1\). In the book-and-magazineexample, let \(t_1\) denote the point in time that the first statementrefers to, and \(t_2\) the moment when the second information wasgiven in Case 2. The original belief set contained the pair \(\langle\neg(p\leftrightarrow q),t_1\rangle\). (\(\neg(p\leftrightarrow q)\)is the exclusive disjunction of \(p\) and \(q\).) Revision by \(p\)can be represented by the incorporation of \(\langle p,t_1\rangle\),and updating by \(p\) by the incorporation of \(\langle p,t_2\rangle\)into the belief set. It follows quite naturally that \(\langle \negq,t_1\rangle\) is implied by the revised belief set but not by theupdated belief set.

6.2 Consolidation

If a belief base is inconsistent, then it can be made consistent byremoving enough of its more dispensable elements. This operation iscalled consolidation. The consolidation of a belief base \(A\) isdenoted \(A!\). A plausible way to perform consolidation is tocontract by falsum (contradiction), i.e. \(A! = A\div\smbot\).

Unfortunately, this recipe for consolidation of inconsistent beliefbases does not have a plausible counterpart for inconsistent beliefsets. The reason is that since belief revision operates withinclassical logic, there is only one inconsistent belief set. Once aninconsistent belief set has been obtained, all distinctions have beenlost, and consolidation cannot restore them.

6.3 Semi-revision

By non-prioritized belief change is meant a process in which newinformation is received, and weighed against old information, with nospecial priority assigned to the new information due to its novelty. A(modified) revision operation that operates in this way is called asemi-revision. Semi-revision of \(K\) by a sentence \(p\) can bedenoted \(K?p\). A sentence \(p\) that contradicts previous beliefs isaccepted only if it has more epistemic value than the original beliefsthat contradict it. In that case, enough of the previous sentences aredeleted to make the resulting set consistent. Otherwise, the input isitself rejected.

One way to construct semi-revision on a belief base \(A\) is to let itconsist of two suboperations:

- Expand \(A\) by \(p\).

- Restore consistency by giving up either \(p\) or some originalbelief(s).

This amounts to defining semi-revision in terms of expansion andconsolidation:

\[A?p = (A +' p)!\]This identity cannot be used for belief sets. Since all inconsistentbelief sets are identical, an operation ? such that \(K?p = (K+p)!\)will have the extremely implausible property that if \(\neg p_1 \inK_1\) and \(\neg p_2 \in K_2\), then \(K_1 ?p_1 = K_2 ?p_2\). However,other ways to perform semirevision on belief sets have been proposed,in particular, the following two-step process:

- Decide whether the input \(p\) should be accepted orrejected.

- If \(p\) was accepted, revise by \(p\).

A simple way to apply this recipe is David Makinson’s (1997)screened revision, in which there is a set \(X\) of potentialcore beliefs that are immune to revision. The belief set \(K\) shouldbe revised by the input sentence \(p\) if \(p\) is consistent with theset \(X\cap K\) of actual core beliefs, otherwise not. The second stepof screened revision is a revision of \(K\) by \(p\), but with therestriction that no element of \(X\cap K\) is allowed to beremoved.

Another variant of the same recipe is calledcredibility-limitedrevision. It is based on the assumption that some inputs areaccepted, others not. Those that are accepted form the set C ofcredible sentences. If \(p \in\) C, then \(K?p = K* p\). Otherwise,\(K?p = K\). This construction can be further specified by choosing anoperation of revision and assigning properties to the set C. A varietyof such constructions have been investigated (Hanssonet al.2001).

6.4 Selective revision

Selective revision is a generalization of semi-revision. Insemi-revision, the input information is either rejected or fullyaccepted. In selective revision, it is possible for only a part of theinput information to be accepted. An operation \(\circ\) of selectiverevision can be constructed from a standard revision operation \(*\)and a transformation function \(f\) from and to sentences:

\[K \circ p = K * f(p)\]In the intended cases, \(f(p)\) does not contain any information thatis not contained in \(p\). This is ensured if \(f(p)\) is a logicalconsequence of \(p\). By adding further conditions on \(f\), variousadditional properties can be obtained for the operation of selectiverevision.

6.5 Shielded contraction

The Success postulate of contraction requires that allnon-tautological beliefs are retractable. This is not a fullyrealistic requirement, since actual agents are known to have beliefsof a non-logical nature that nothing can bring them to give up. Inshielded contraction, some non-tautological beliefs cannot be givenup; they are shielded from contraction. Shielded contraction can bebased on an ordinary contraction \(\div\) and a set \(R\) ofretractable sentences. If \(p \in R\), then \(K-p = K\div p\).Otherwise, \(K-p = K\).

This construction can be further specified by adding variousrequirements on the structure of \(R\). Close connections have beenshown to hold between shielded contraction and semi-revision.(Fermé and Hansson 2001)

6.6 Replacement

By replacement is meant an operation that replaces one sentence byanother in a belief set. It is an operation with two variables, suchthat \([p/q]\) replaces \(p\) by \(q\). Hence, \(K[p/q]\) is a beliefset that contains \(q\) but not \(p\).

Replacement aims both at the removal of a sentence \(p\) and theaddition of a sentence \(q\). This amounts to two success conditions,\(p \not\in K[p/q]\) and \(q \in K[p/q]\). However, these twoconditions cannot both be satisfied without exception. First, just asfor belief contraction, an exception must be made from the first ofthem in the case when \(p\) is a tautology and so cannot be removed.Secondly, the two conditions are not compatible in cases when \(q\)logically implies \(p\). This can be dealt with by extending theexception that is provided for in the Success postulate forcontraction from cases when \(p \in \Cn(\varnothing)\) to cases when\(p \in \Cn(\{q\})\). This gives rise to the following two successconditions:

Contractive success:

If \(p \not\in \Cn(\{q\})\), then \(p \not\in \Cn(K[p/q]\)).

Revision success:

\(q \in K[p/q]\)

Replacement can be used as a kind of “Sheffer stroke” forbelief revision, i.e. as an operation in terms of which the otheroperations can be defined. Contraction by \(p\) can be defined as\(K[p/\smtop]\) and revision by \(p\) as \(K[\smbot/p]\), where\(\smbot\) is falsum and \(\smtop\) is tautology. Provided that theunperformable suboperation of removing the tautology \(\smtop\) istreated as an empty suboperation, expansion by \(p\) can be defined as\(K[\smtop/p]\).

6.7 Merge

If the belief set \(K\) has a finite base, then it can be representedby a single sentence, namely the conjunction \(k\) of all the elementsof its base. This means that the revision \(K* p\) of a belief set\(K\) by a sentence \(p\) can be replaced by a revision \(k* p\) of asentence by another sentence. If this revision is non-prioritized, wemay treat \(k\) and \(p\) equally, so that \(k* p = p* k\). Such anoperation can be described as the merging of two beliefrepresentations. It can represent a process of conflict resolutionthrough selective combination of information from two agents orsources. This operation can also be generalized to the merge ofseveral elements, representing efforts to combine information fromseveral agents or sources (Konieczny and Pino Pérez 2011).

6.8 Multiple contraction and revision

By multiple contraction is meant the simultaneous contraction of morethan one sentence. Similarly, multiple revision is revision by morethan one sentence.

There are two major types of multiple contraction. Inpackagecontraction, all elements of the input set are retracted: theyhave to go in a package. Inchoice contraction it suffices toremove at least one of them. Hence, the success conditions for the twotypes of multiple contraction are as follows:

Package success:

If \(B\cap \Cn(\varnothing) = \varnothing\) then \(B\cap \Cn(A\div B)= \varnothing\)

Choice success:

If \(B\) is not a subset of \(\Cn(\varnothing)\), then \(B\) is not asubset of \(\Cn(A\div B)\).

Partial meet contraction and kernel contraction can both begeneralized fairly straight-forwardly to both package and choicevariants of multiple contraction.

The construction of package revision gives rise to an interestingextension of the notion of negation. The reason why contraction by\(\neg p\) is performed as a suboperation of revision by \(p\) is that\(p\) can be consistently added to a set if and only if it does notimply \(\neg p\). It turns out that (in a logic satisfyingcompactness) a set \(B\) can be consistently added to another set ifand only if this other set does not imply any element of the set\(\neg B\), that is defined as follows:

Negation of a set:

\(p \in \neg B\) if and only if \(p\) is either a negation of anelement of \(B\cup \{\smtop\}\) or a disjunction of negations ofelements of \(B\cup \{\smtop\}\).

Therefore multiple revision can be defined from (package) multiplecontraction and expansion via a generalized Levi identity:

\[ K* B = (K\div \neg B)+B\]Most of the major AGM-related contraction operations have beengeneralized to multiple contraction: multiple partial meet contraction(Hansson 1989, Fuhrmann and Hansson 1994, Li 1998), multiple kernelcontraction (Ferméet al. 2003), multiple specifiedmeet contraction (Hansson 2010), and a multiple version ofGrove’s sphere system (Reis and Fermé 2011, Ferméand Reis 2012).

6.9 Indeterministic belief change

Most models of belief change aredeterministic in the sensethat given a belief set and an input, the resulting belief set iswell-determined. There is no scope for chance in selecting the newbelief set. Clearly, this is not a realistic feature, but it makes themodels much simpler and easier to handle, not least from acomputational point of view. Inindeterministic beliefchange, the subjection of a specified belief set to a specified inputhas more than one admissible outcome.

Indeterministic operations can be constructed as sets of deterministicoperations. Hence, given three revision operations \(* , * '\) and \(*''\) the set \(\{*\),\(* '\),\(*''\)\(\}\) can be used as an indeterministicoperation. The success condition is simply:

\[K\{* , * ', * ''\}p \in \{K* p, K* 'p, K* ''p\}\]Lindström and Rabinowicz (1991) constructed indeterministiccontraction by giving up the assumption that epistemic entrenchmentsatisfies connectedness. This resulted in Grove’s sphere systemswith “fallbacks” that are not linearly ordered but stillall include the original belief set. Fazio and Baldi (2021) have usedindeterministic contraction in an investigation of algebraiccounterparts to both the AGM model and some closely related models ofbelief change.

6.10 Operations for an extended language

Belief revision theory has been almost exclusively developed withinthe framework of classical sentential (truth-functional) logic. Theinclusion of non-truthfunctional expressions into the language hasinteresting and indeed drastic effects. In particular, this applies toconditional sentences.

Many types of conditional sentences, such as counterfactualconditionals, cannot be adequately expressed with truth-functionalimplication (material implication). Several formal interpretations ofconditional sentences have been proposed. One of them, namely theRamsey test, is particularly well suited to the formalframework of belief revision. It is based on a suggestion by F. P.Ramsey that has been further developed by Robert Stalnaker and others(Stalnaker 1968). The basic idea is that “if \(p\) then\(q\)” is taken to be believed if and only if \(q\) would bebelieved after revising the present belief state by \(p\). Let\(p\Rightarrow q\) denote “if \(p\) then \(q\)”, or moreprecisely: “if \(p\) were the case, then \(q\) would be thecase”. In order to treat conditional statements on par withstatements about actual facts, they will have to be included in thebelief set, thus:

The Ramsey test:

\((p\Rightarrow q) \in K\) if and only if \(q \in K* p\).

However, inclusion in the belief set of conditionals that satisfy theRamsey test will require radical changes in the logic of beliefchange. As one example of this, contraction cannot then satisfy theinclusion postulate \((K\div p \subseteq K)\). The reason for this isthat contraction typically provides support for conditional sentencesthat were not supported by the original belief state. This can be seenfrom the following example:

If I give up my belief that John is mentally retarded, then I gainsupport for the conditional sentence “If John has lived 30 yearsin London, then John understands the English language.”

A famous impossibility theorem by Peter Gärdenfors (1986, 1987)shows that the Ramsey test is incompatible with a set of plausiblepostulates for revision. Several solutions to the impossibilitytheorem have been put forward. One option is to reject the Ramsey testas a criterion for the validity of conditional sentences (Rott 1986).Another, proposed by Isaac Levi, is to accept the test as a criterionof validity but deny that such conditional sentences should beincluded in the belief set when they are valid (Levi 1988.Arló-Costa 1995. Arló-Costa and Levi 1996). Severalother proposals have been put forward. However, it is fair to say thatoperations of AGM-style belief change have not yet been constructedthat are generally recognized as able to deal adequately withconditional or modal sentences.

6.11 Resource-bounded belief change

The AGM model and most related models of belief change assume highlyidealized reasoners who have unlimited cognitive capacities. Harman(1986) developed a set of rationality principles for resource-boundedepistemic agents. Wassermann (1999), Alechina (2006), Doyle (2013) andothers have developed models of belief change for agents with limitedcognitive capacities. The use of finite belief bases (section 5) canbe seen as a way to avoid the operations on infinite belief sets thatare standard in AGM. Operations on infinite sets can require infiniteresources, which makes such operations impossible for agents withfinite resources.

6.12 Changes in the strength of beliefs

An operation of change can raise or lower the position of a sentencein the ordering without affecting the belief set (but affecting howthe belief state responds to new inputs). An operation ofimprovement, as proposed by Konieczny and Pérez (2008)increases the plausibility of a non-believed sentence \(p\) by movingsome of the \(p\)-worlds to a higher position in the preferenceordering of worlds. Even if such a change does not lead to \(p\)becoming a belief, its acceptance in later, additional operations canbe facilitated.

An operation of change can be so constructed that it adjusts theposition of the input sentence in an ordering to be the same as thatof a reference sentence. This means that two sentences have to bespecified in the input: the (input) sentence to be moved and the(reference) sentence indicating its new position. Hans Rott (2007,Other Internet Resources) called such operators two-dimensional. JohnCantwell (1997) classified them asraising orlowering, depending on the direction of change. (See alsoFermé and Rott 2004 and Rott 2009.)

6.13 Changes in norms and preferences

There are close parallels between changes in norms and changes inbeliefs. In order to apply a norm system with conflicting norms to aparticular situation, some of the norms may have to be ignored. Theproblem how to prioritize among conflicting norms is similar to theselection of sentences for removal in belief contraction (Hansson andMakinson 1997). The AGM model was in fact partly the outcome ofattempts to formalize changes in norms rather than beliefs(Alchourrón and Makinson 1981). In spite of this, authors whoapply the AGM model to norms have found it in need of rather extensivemodifications to make it suitable for that purpose. Hence, in theirmodel of changes in legislation, Governatori and Rotolo (2010)introduced an explicit representation of time in order to account forphenomena such as retroactivity.

A model of changes in preferences can be obtained by replacing thestandard AGM language by sentences of the form \(p \ge q\)(“\(p\) is at least as good as \(q\)”) and theirtruth-functional combinations. The adoption of a new preference canthen take the form of revision by such a preference sentence. Partialmeet contraction can be used, but some modifications of the AGM modelseem to be necessary in applications to preferences (Hansson 1995,Lang and van der Torre 2008, Grüne-Yanoff and Hansson 2009).

7. Iterated change

The preceding sections have only dealt with changes of one and thesame belief set or belief base. This is clearly a severe limitation. Arealistic model of belief change should allow for repeated (iterated)changes, such as \(K\div p\div q* r* s\div t\ldots\) In other words,operations are needed that can contract or revise any belief set(belief base) by any sentence. Such operations are calledglobal, in contrast tolocal operations that aredefined only for a single specified set.

An obvious way to obtain a global operation ofpartial meetcontraction would be to use the same selection function for allsets to be contracted. However, with the standard way to obtain apartial meet contraction from a selection function, this is notpossible, due to the way selection functions treat the empty set. Theway selection functions have traditionally been defined, if \(A\bot p= \varnothing\), then \(\gamma(A\bot p ) = \{A\}\). As a consequenceof this, if \(\gamma\) is a selection function for \(A\), and \(A \neB\), then \(\gamma\) is not a selection function for \(B\). For let\(A\bot p = B\bot p = \varnothing\). For \(\gamma\) to be a functionit must be the case that \(\gamma(A\bot p) = \gamma(B\bot p)\). For\(\gamma\) to be a selection function for \(A\) it must be case that\(\gamma(A\bot p) = \{A\}\), and in order for it to be a selectionfunction for \(B\) it must be the case that \(\gamma(B\bot p) =\{B\}\). Since \(A \ne B\), this is impossible.

This can be solved if we rewrite the definition of partial meetcontraction as follows:

Alternative definition of partial meet contraction:

\((1')\) \(\gamma(K\bot p) \subseteq K\bot p\), and if \(K\bot p \ne\varnothing\), then \(\gamma(K\bot p) \ne \varnothing\).

\((2')\) \(K\div p = \bigcap \gamma(K\bot p)\), unless \(\gamma(K\botp) = \varnothing\), in which case \(K\div p = K\).

As applied to a single belief set \(K\), this definition is equivalentwith the original definition. Notably, it yields the same result asthe original definition even in the limiting case when \(p\) is atautology, but it avoids using the selection function in this limitingcase. With this, slightly adjusted, definition, one and the sameselection function can be used for all belief sets, and consequentlywe can construct iterated change using only one, AGM-style, selectionfunction. Since partial meet revision is definable from partial meetcontraction via the Levi identity, this means that we have globaloperations for both contraction and revision. This construction is sogeneral that it does not impose any new properties on contraction orrevision, i.e. no properties in addition to the usual AGM postulates(Hansson 2012).

However, most of the discussion on iterated change has been based onthe assumption that such additional properties are plausible andindeed desirable. The so-called Darwiche-Pearl postulates for revisionhave had a central role in these discussions (Darwiche and Pearl1997):

If \(q \vdash p\), then \((K * p) * q = K * q\). (DP1)

If \(q \vdash \neg p\), then \((K * p) * q = K * q\). (DP2)

If \(K * q \vdash p\), then \((K * p) * q \vdash p\). (DP3)

If \(K * q\) ⊬ \(\neg p\), then \((K * p) * q\) ⊬ \(\negp\) (DP4)

The Darwiche-Pearl postulates express an intuition about the epistemicordering of possible worlds, namely that when we revise by a sentence\(p\), then the ordering among \(p\)-worlds should be unchanged, andso should the ordering among \(\neg p\)-worlds. The change takes theform of a shift of the relative positions of these two parts of theoriginal ordering of worlds. A large number of proposals for suchshifts have been put forward, but opinions differ widely on theadequacy of these proposals.

Abhaya Nayak (1994) has proposed a model of iterated belief change inwhich both the belief states and the inputs are binary relations thatsatisfy the standard entrenchment postulates except Minimality. Inputsof this type may be seen as “fragments” of belief states,to be incorporated into the previous belief state. In the same vein,Eduardo Fermé and Hans Rott (2004) have investigated beliefrevision with inputs of the more general form: “accept \(q\)with a degree of plausibility that at least equals that of\(p\)”. They call thisrevision by comparison. Beliefstates are represented by entrenchment orderings. Hence, from anentrenchment ordering \(\le\) and such a generalized input a newentrenchment ordering \(\le '\) is obtained that contains theinformation needed to construct the new belief set.

8. Alternative accounts

In spite of the dominant position of the AGM model and its closevariants, several other formal models of belief changes have beenproposed.

8.1 Learning theory

In belief revision theory, the focus is on consistency rather thantruthfulness. In contrast, learning theory is devoted to induction andthe attainment of true beliefs. A research question is represented asa partition of the set of possible worlds, i.e. a distribution of allpossible worlds into non-overlapping sets. The research question hasbeen fully answered when it is known which of these partitionscontains the actual world. Information received by the agentsuccessively narrows down the set of partitions that may contain it.The central issue is how to construct an inductive strategy, i.e. astrategy for which investigations to perform and in what order, andhow to interpret them (Kelly 1999). Although this problem hasconnections with belief revision, operations not satisfying thestandard AGM postulates have usually played a prominent role in thediscussion. (Genin and Kelly 2019)

8.2 Dynamic logics of belief change

Dynamic doxastic logic (DDL) was introduced by Krister Segerberg torepresent an agent who has opinions about the external world andchanges these opinions upon receipt of new information. DDL makes useof epistemic modal operators of the type introduced by Hintikka(1962). The sentence \(B_i p\) denotes that the individual \(i\)believes that \(p\). When only one agent is under consideration, thesubscript can be deleted, and the operator \(B\) can be read “itis believed that” or “the agent believes that”(Segerberg 1995, p. 536).

The formula \(Bp\) in DDL differs from the expression \(p \in K\) ofAGM in being a sentence in the same language as \(p\). This makes itpossible to express in the object language that a sentence isbelieved. In this way, Segerberg attempted to develop belief revision“as a generalization of ordinary Hintikka type doxasticlogic”, whereas in contrast “AGM is not really logic; itis a theory about theories” (Segerberg 1999, p. 136). In the DDLframework it is possible to express beliefs about beliefs. Thesentence “\(i\) believes that \(i\) does not believe that\(p\)” can be expressed as \(B_i \neg B_i p\), whereas there isno way to express it in the AGM framework. \(((p \not\in K_i) \inK_i\) is not a well-formed formula.)

In DDL, belief revision operations (expansion, revision, andcontraction) are expressed with dynamic modal operators, similar tothose used for program execution. (This element of DDL was presentalso in previous publications by several authors. See Fuhrmann 1991;de Rijke 1994; van Benthem 1989 and 1995.) Segerberg used thefollowing notation:

| \([\div p]q\) | (\(q\) holds after contraction by \(p)\) |

| \([* p]q\) | (\(q\) holds after revision by \(p)\) |

| \([+ p]q\) | (\(q\) holds after expansion by \(p)\) |

The combination of these two elements, belief operators and dynamicoperators, results in a framework that differs from AGM in importantways. (Leitgeb and Segerberg 2007, 169)

Largely similar systems have been developed under the name of DynamicEpistemic Logic, DEL (Plaza 1989; Baltag et al. 1998; van Ditmarsch etal. 2007; see the entry ondynamic-epistemic logic). A major difference between DDL and DEL is that the latter has mostlybeen studied in multiagent contexts. The most studied dynamics is thatof the public announcement of some sentence (van Ditmarsch et al.2007).

8.3 Descriptor revision

Descriptor revision (Hansson 2017) is based on two major formalconstructions. One of them is a metalinguistic belief predicate\(\mathfrak{B}\) that is applied to sentences of the object language.\(\mathfrak{B}p\) denotes that the sentence \(p\) is believed, \(\neg\mathfrak{B}p\) that it is not believed, and \(\mathfrak{B}p\vee\mathfrak{B}q\) that either \(p\) or \(q\) is believed. Such sentencescan be used to express the success conditions of belief changeoperations. Thus \(\mathfrak{B}p\) is the success condition ofrevision by \(p\), \(\neg \mathfrak{B}p\) that of contraction by \(p\)and \(\{\neg \mathfrak{B}p,\neg \mathfrak{B}q\}\) that of multiplecontraction by \(\{p,q\}\). Due to the versatility of descriptors weonly need one operation, denoted \(\circ\). Hence, \(K\circ\mathfrak{B}p\) represents revision by \(p\) and \(K \circ \neg\mathfrak{B}p\) contraction by \(p\).

The other major formal construction is a choice function (selectionfunction) that operates directly on the set of potential outcomes ofan operation. Hence, the operation \(K \circ \mathfrak{B}p\) isperformed by choosing one among the potential belief sets that contain\(p\) (presumably that which is most choiceworthy, or closest athand). Operations based on these principles have been axiomaticallycharacterized. Notably, the recovery postulate that creates problemsin the AGM framework does not hold in the descriptor revisionframework. The application of a choice function to potential beliefoutcomes is arguably more plausible than its application to possibleworlds or remainders, since the latter two entities are logicallyinfinite (if the language is so), and therefore cognitivelyinaccessible.

Descriptor revision makes it possible to investigate operations ofchange more generally, and to discuss properties that can hold foroperations with different types of the success conditions. Let \(\Psi\) and \( \Xi\) be descriptors, i.e. sets of sentences containingthe \( \mathfrak{B}\) operator. Let \(K ⊩\Psi\) denote that\(K\) satisfies all the conditions in \(\Psi\). Some examples of suchgeneral properties of descriptor revision are:

Closure:

\(K \circ \Psi = \Cn(K \circ \Psi)\)

Relative success:

\(K \circ \Psi ⊩ \Psi\) or \( K \circ \Psi=K\)

Regularity:

If \(K \circ \Xi ⊩ \Psi\), then \(K \circ \Psi ⊩\Psi\)

Confirmation:

If \(K ⊩\Psi\), then \(K \circ \Psi=K)\)

Cumulativity:

If \(K \circ \Psi ⊩\Xi\), then \(K \circ \Psi = K \circ(\Psi\cup\Xi) \)

8.4 Bayesian models

The AGM model and other logical frameworks for belief revision arebased on a dichotomous approach to belief: either something isbelieved or it is not, in either case without any gradations. Beliefscan be be more or less easily given up, and non-beliefs can be more orless easily turned into beliefs, but the very act of believing doesnot admit of degrees. In contrast, probabilistic models of belief,usually based on some form of subjective Bayesianism, admit alldegrees between the strongest belief and the strongest disbelief.Dichotomous and probabilistic models represent different features ofbelief systems. It has proved to be difficult to construct areasonably manageable model that covers both the logic-related and theprobabilistic properties of belief change. These difficulties areclosely connected with the lottery and preface paradoxes (Kyburg 1961;Makinson 1965).

However, belief revision theory has turned out to be useful in dealingwith the problematic limiting case of conditional probabilities with acondition that has probability zero. Insights from belief revisiontheory have been used in the construction of non-standard models ofprobabilities in which conditionalization can be performed also inthis limiting case (Makinson 2011).

Bibliography

Citations annotated insmaller text referto books or articles that are recommended for further introductoryreading.

- Alchourrón, C.E., P. Gärdenfors, and D. Makinson,1985, “On the Logic of Theory Change: Partial Meet Contractionand Revision Functions”,Journal of Symbolic Logic, 50:510–530.

[The starting-point for allsubsequent studies of belief revision.] - Alchourrón, C.E. and D. Makinson, 1981, “Hierarchiesof Regulation and Their Logic”, in R. Hilpinen (ed.),NewStudies in Deontic Logic, Dordrecht: D. Reidel PublishingCompany, pp. 125–148.

- Alchourrón, C.E. and D. Makinson, 1982, “On the logicof theory change: Contraction functions and their associated revisionfunctions”,Theoria, 48: 14–37.

- Alechina, N., M. Jago, and B. Logan, 2006, “Resource-boundedbelief revision and contraction”,Lecture Notes in ComputerScience, 3904: 141–154.

- Arló-Costa, H., 1995, “Epistemic conditionals, snakesand stars”, in G. Crocco, L. Fariñas del Cerro, and A.Herzig (eds.), Conditionals: from Philosophy to ComputerScience,Studies in Logic and Computation (Volume 5),Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Arló-Costa, H. and I. Levi, 1996, “Two notions ofepistemic validity”,Synthese, 109: 217–262.

- Baltag, A., Moss, L., and Solecki, S., 1998, “The logic ofpublic announcements, common knowledge, and private suspicions”,in I. Gilboa (ed.),Proceedings of the 7th conference ontheoretical aspects of rationality and knowledge (TARK’98), San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann, pp. 43–56.

- Berto, F., 2019, “Simple hyperintensional beliefrevision”,Erkenntnis, 84: 559–575.

- Cantwell, J., 1997, “On the logic of small changes inhypertheories”,Theoria, 63: 54–89.

- –––, 1999, “Some logics of iteratedrevision”,Studia Logica, 7: 49–84.

[Iteratedrevision.] - Darwiche, A. and J. Pearl, 1997, “On the logic of iteratedbelief revision”,Artificial Intelligence, 89: 1–29.

- de Rijke, M., 1994, “Meeting some neighbours”, in J.van Eijck, and A. Visser (eds.)Logic and information flow,Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp. 170–195.

- Doyle, J., 1979, “A Truth Maintenance System”,Artificial Intelligence, 12: 231–272.

- –––, 2013, “Mechanics and mentalchange”. In B.O. Küppers et al. (eds)Evolution ofSemantic Systems, pp. 127–150. Springer: Cham.

- Fagin, R., J.D. Ullman, and M.Y. Vardi, 1983, “On thesemantics of updates in databases”,Proceedings of SecondACM SIGACT-SIGMOD, pp. 352-365.

- Fazio, D. and M. Pra Baldi, 2021, “On a logico-algebraicapproach to AGM belief contraction theory”,Journal ofPhilosophical Logic, 50: 911–938.

- Fermé, E. and S.O. Hansson, 2001, “ShieldedContraction”, pp. 85–107 in H. Rott and M.-A. Williams(eds.),Frontiers of Belief Revision, Dordrecht: Kluwer.

- –––, 2018,Belief Change. Introduction andOverview, Springer: Cham.

[Overview of results fromstudies of belief revision in the AGM tradition and relatedapproaches.] - Fermé, E. and M.D.L. Reis, 2012, “System ofSpheres-based Multiple Contractions”,Journal ofPhilosophical Logic, 41: 29–52.

- Fermé, E. and H. Rott, 2004, “Revision bycomparison”,Artificial Intelligence, 157:5–47.

- Fermé, E., K. Saez, and P. Sanz, 2003, “MultipleKernel Contraction”,Studia Logica, 73:183–195.

- Fuhrmann, A., 1991, “Theory contraction through basecontraction”,Journal of Philosophical Logic, 20:175–203.

- Fuhrmann, A. and S.O. Hansson, 1994, “A Survey of MultipleContraction”,Journal of Logic, Language andInformation, 3: 39–74.

[Multiplecontraction] - Gärdenfors, P., 1978, “Conditionals and Changes ofBelief”,Acta Philosophica Fennica, 30: 381–404.

- –––, 1981, “An Epistemic Approach toConditionals”,American Philosophical Quarterly, 18:203–211.

- –––, 1986, “Belief Revision and the RamseyTest for Conditionals”,Philosophical Review, 95:81–93.

[The Ramsey Test.] - –––, 1987, “Variations on the Ramsey Test:More triviality results”,Studia Logica, 46:319–325.

- –––, 1988,Knowledge in Flux. Modeling theDynamics of Epistemic States, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

[The AGM model.] - –––, 2011, “Notes on the history of ideasbehind AGM”,Journal of Philosophical Logic, 40:115–120.

- Gärdenfors, P., and D. Makinson, 1988, “Revisions ofKnowledge Systems Using Epistemic Entrenchment”,SecondConference on Theoretical Aspects of Reasoning about Knowledge,pp. 83–95.

- Genin, K. and K.T. Kelly, 2019,“Theory Choice, TheoryChange, and Inductive Truth-Conduciveness”,StudiaLogica, 107: 949–989.

- Governatori, G. and A. Rotolo, 2010, “Changing legalsystems: legal abrogations and annulments in Defeasible Logic”,Logic Journal of IGPL, 18: 157–194.

- Grove, A., 1988, “Two Modellings for Theory Change”,Journal of Philosophical Logic, 17: 157–170.

[The propositional model ofbelief change.] - Grüne-Yanoff, T. and S.O. Hansson, 2009, “From BeliefRevision to Preference Change”, in T. Grüne-Yanoff and S.O.Hansson (eds.),Preference Change: Approaches from Philosophy,Economics and Psychology, Berlin: Springer, pp.159–184.

- Hansson, S.O., 1989, “New Operators for TheoryChange”,Theoria, 55: 114–132.

- –––, 1995, “Changes in Preference”,Theory and Decision, 38: 1–28.

- –––, 1999,A Textbook of Belief Dynamics.Theory Change and Database Updating, Dordrecht: Kluwer.

[Contains more details, andreferences, on most of the topics treated in this entry.] - –––, 2003, “Ten Philosophical Problems inBelief Revision”,Journal of Logic and Computation, 13:37–49.

[Connections between beliefrevision and issues in informal philosophy.] - –––, 2010, “Multiple and IteratedContraction Reduced to Single-Step Single-Sentence Contraction”,Synthese, 173: 153–177.

- –––, 2012, “Global and iteratedcontraction and revision: An exploration of uniform and semi-uniformapproaches”,Journal of Philosophical Logic, 41(1):143–172.

- –––, 2017,Descriptor RevisionSpringer: Cham. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Hansson, S.O., Fermé, E., Cantwell, J., and Falappa, M.,2001, “Credibility-Limited Revision”,Journal ofSymbolic Logic, 66: 1581–1596.

[Non-prioritized beliefrevision.] - Hansson, S.O. and D. Makinson, 1997, “Applying Normativerules with restraint”, in M.L. Dalla Chiara,et al.(eds.),Logic and Scientific Method, Dordrecht: KluwerAcademic Publishers, pp 313–332.

- Harman, G., 1986,Change in View – Principles ofReasoning. MIT Press.

- Harper, W., 1977, “Rational Conceptual Change”,PSA 1976, pp. 462–494.

- Hintikka, J., 1962,Knowledge and belief: An introduction tothe logic of the two notions, Ithaca: Cornell UniversityPress.