Agent-Based Modeling in the Philosophy of Science

Agent-based models (ABMs) are computational models that simulatebehavior of individual agents in order to study emergent phenomena atthe level of the community. Depending on the application, agents mayrepresent humans, institutions, microorganisms, and so forth. Theagents’ actions are based on autonomous decision-making andother behavioral traits, implemented through formal rules. Bysimulating decentralized local interactions among agents, as well asinteractions between agents and their environment, ABMs enable us toobserve complex population-level phenomena in a controlled and gradualmanner.

This entry focuses on the applications of agent-based modeling in thephilosophy of science, specifically within the realm of formal socialepistemology of science. The questions examined through these modelsare typically of direct relevance to philosophical discussionsconcerning social aspects of scientific inquiry. Yet, many of thesequestions are not easily addressed using other methods since theyconcern complex dynamics of social phenomena. After providing a briefbackground on the origins of agent-based modeling in philosophy ofscience (Section 1), the entry introduces the method and its applications as follows. Webegin by surveying the central research questions that have beenexplored using ABMs, aiming to showwhy this method has beenof interest in philosophy of science (Section 2). Since each research question can be approached through variousmodeling frameworks, we next delve into some of the common frameworksutilized in philosophy of science to showhow ABMs tacklephilosophical problems (Section 3). Subsequently, we revisit the previously surveyed questions andexamine the insights gained through ABMs, addressingwhat hasbeen found to answer each question (Section 4). Finally, we turn to the epistemology of agent-based modeling and theunderlying epistemic function of ABMs (Section 5). Given the often highly idealized nature of ABMs, we examinewhichepistemic roles support the models’ capacity to engage withphilosophical issues, whether for exploratory or explanatory goals.The entry concludes by offering an outlook on future researchdirections in the field (Section 6).

Since the literature on agent-based modeling of science is vast andgrowing, it is impossible to give an exhaustive survey of modelsdeveloped on this topic. Instead, this entry aims to provide asystematic overview by focusing on paradigmatic examples of ABMsdeveloped in philosophy of science, with an eye to their relevancebeyond the confines of formal social epistemology.

- 1. Origins

- 2. Central Research Questions

- 3. Common Modeling Frameworks

- 4. Central Results

- 5. Epistemology of Agent-Based Modeling

- 6. Conclusion and Outlook

- Bibliography

- Academic Tools

- Other Internet Resources

- Related Entries

1. Origins

The method of agent-based modeling was originally developed in the1970s and ’80s with models of social segregation (Schelling1971; Sakoda 1971; see also Hegselmann 2017) and cooperation (Axelrod& Hamilton 1981) in social sciences, and under the name of“individual-based modeling” in ecology (for an overviewsee Grimm & Railsback 2005). Following this tradition, ABMs drewthe interest of scholars studying social aspects of scientificinquiry. By representing scientists as agents equipped with rules forreasoning and decision-making, agent-based modeling could be used tostudy the social dynamics of scientific research. As a result, ABMs ofscience have been developed across various disciplines that includescience in their subject domain: from sociology of science,organizational sciences, cultural evolution theory, theinterdisciplinary field of meta-science (or “science ofscience”), to social epistemology and philosophy of science.While ABMs developed in philosophy of science often tackle themes thatare similar or related to those examined by ABMs of science in otherdomains, they are motivated by philosophical questions—issuesembedded in the broader literature in philosophy of science. Theirintroduction was influenced by several parallel research lines:analytical modeling in philosophy of science, computational modelingin related philosophical domains, and agent-based modeling in socialsciences. In the following, we take a brief look at each of theseprecursors.

One of the central ideas behind the development of formal socialepistemology of science is succinctly expressed by Philip Kitcher inhisThe Advancement of Science:

The general problem of social epistemology, as I conceive it, is toidentify the properties of epistemically well-designed social systems,that is, to specify the conditions under which a group of individuals,operating according to various rules for modifying their individualpractices, succeed, through their interactions, in generating aprogressive sequence of consensus practices. (Kitcher 1993: 303)

Such a perspective on social epistemology of science highlighted theneed for a better understanding of the relationship between individualand group inquiry. Following the tradition of formal modeling ineconomics, philosophers introduced analytical models to study tensionsinherent to this relationship, such as the tension between individualand group rationality. In this way, they sought to answer thequestion: how can individual scientists, who may be driven bynon-epistemic incentives, jointly form a community that achievesepistemic goals? Most prominently, Goldman and Shaked (1991) developeda model that examines the relationship between the goal of promotingone’s professional success and the promotion oftruth-acquisition, whereas Kitcher (1990, 1993) proposed a model ofthe division of cognitive labor, showing that a community consistingof scientists driven by non-epistemic interests may achieve an optimaldistribution of research efforts. This work was followed by a numberof other contributions (e.g., Zamora Bonilla 1999; Strevens 2003).Analytic models developed in this tradition endorsed economicapproaches to the study of science, rooted in the idea of a“generous invisible hand”, according to which individualsinteracting in a given community can bring about consequences that arebeneficial for the goals of the community without necessarily aimingat those consequences (Mäki 2005).

Around the same time, computational methods entered the philosophicalstudy of rational deliberation and cooperation in the context of gametheory (Skyrms 1990, 1996; Grim, Mar, & St. Denis 1998), theoryevaluation in philosophy of science (Thagard 1988) and the study ofopinion dynamics in social epistemology (Hegselmann & Krause 2002,2005; Deffuant, Amblard, Weisbuch, & Faure 2002). Computationalmodels introduced in this literature included ABMs: for instance, acellular automata model of the Prisoner’s Dilemma, or modelsexamining how opinions change within a group of agents.

Agent-based modeling was first applied to the study of science insociology of science, with the model developed by Nigel Gilbert (1997)(cf. Payette 2011). Gilbert’s ABM aimed at reproducingregularities that had previously been identified in quantitativesociological research on indicators of scientific growth (such as thegrowth rate of publications and the distribution of citations perpaper). The model followed an already established tradition ofsimulations of artificial societies in social sciences (cf. Epstein& Axtell 1996). In contrast to abstract and highly-idealizedmodels developed in other social sciences (such as economics andarchaeology), ABMs in sociology of science tended towards anintegration of simulations and empirical studies used for theirvalidation (cf. Gilbert & Troitzsch 2005).

Soon after, ABMs were introduced to the philosophy of science throughpioneering works by Zollman (2007), Weisberg and Muldoon (2009), Grim(2009), Douven (2010)—to mention some of the most prominentexamples. In contrast to ABMs developed in sociology of science, theseABMs followed the tradition of abstract and highly-idealized modeling.Similar to analytical models, they were introduced to study howvarious properties of individual scientists—such as theirreasoning, decision-making, actions and relations—bring aboutphenomena characterizing the scientific community—such as asuccess or a failure to acquire knowledge. By representing inquiry inan abstract and idealized way, they facilitated insights into therelationship between some aspects of individual inquiry and its impacton the community while abstracting away from numerous factors thatoccur in actual scientific practice. But in contrast to analyticalmodels, ABMs proved to be suitable for scenarios often too complex foranalytical approaches. These scenarios include heterogeneousscientific communities, with individual scientists differing in theirbeliefs, research heuristics, social networks, goals of inquiry, andso forth. Each of these properties can change over time, depending onthe agents’ local interactions. In this way ABMs can show howcertain features characterizing individual inquiry suffice to generatepopulation-level phenomena under a variety of initial conditions.Indeed, the introduction of ABMs to philosophy of science largelyfollowed the central idea of generative social science: to explain theemergence of a macroscopic regularity we need to show howdecentralized local interactions of heterogeneous autonomous agentscan generate it. As Joshua Epstein summed it up: “If youdidn’t grow it, you didn’t explain its emergence”(2006).

2. Central Research Questions

ABMs of science typically model the impact of certain aspects ofindividual inquiry on some measure of epistemic performance of thescientific community. This section surveys some of the centralresearch questions investigated in this way. Its aim is to explain whyABMs were introduced to study philosophical questions, and how theirintroduction relates to the broader literature in philosophy ofscience.

2.1 Theoretical diversity and the incentive structure of science

How does a community of scientists make sure to hedge its bets onfruitful lines of inquiry, instead of only pursuing suboptimal ones?Answering this question is a matter of coordination and organizationof cognitive labor which can generate an optimal diversity of pursuedtheories. The importance of a synchronous pursuit of a plurality oftheories in a given domain has long been recognized in thephilosophical literature (Mill 1859; Kuhn 1977; Feyerabend 1975;Kitcher 1993; Longino 2002; Chang 2012). But how does a scientificcommunity achieve an optimal distribution of research efforts? Whichfactors influence scientists to divide and coordinate their labor in away that stimulates theoretical diversity? In short, how istheoretical diversity achieved and maintained?

One way to address this question is by examining how differentincentives of scientists impact their division of labor. To see therelevance of this question, consider a community of scientists all ofwhom are driven by the same epistemic incentives. As Kitcher (1990)argued, in such a community everyone might end up pursuing the same,initially most promising line of inquiry, resulting in little to nodiversity. Traditionally, philosophers of science tried to addressthis worry by arguing that a diversity in theory choice may resultfrom diverse methodological approaches (Feyerabend 1975), diverseapplications of epistemic values (Kuhn 1977), or from differentcognitive attitudes towards theories, such as acceptance andpursuit-worthiness (Laudan 1977). Kitcher, however, wondered whethernon-epistemic incentives, such as fame and fortune—usuallythought of as interfering with the epistemic goals ofscience—might actually be beneficial for the community byencouraging scientists to deviate from dominant lines of inquiry.

The idea that scientists are rewarded for their achievements throughcredit, which impacts their research choices, had previously beenrecognized by Merton (1973) and Hull (1978, 1988). For example, ascientist may receive recognition for being the first to make adiscovery (known as the “priority rule”), which mayincentivize a specific approach to research. Yet, such non-epistemicincentives could also fail to promote an optimal kind of diversity.For instance, they may result in too much research being spent onfutile hypotheses and/or in too few scientists investigating the besttheories. Moreover, an incentive structure will have undesirableeffects if rewards are misallocated to scientists that arewell-networked rather than assigned to those who are actually first tomake discoveries, or if credit-driven science lowers the quality ofscientific output. This raises the question: which incentivestructures promote an optimal division of labor, without havingepistemically or morally harmful effects?

ABMs provide an apt ground for studying these issues: by modelingindividual scientists as driven by specific incentives, we can examinetheir division of labor and the resulting communal inquiry. We willlook at the models studying these issues inSection 4.1.

2.2 Theoretical diversity and the communication structure of science

Another way to study theoretical diversity is by focusing on thecommunication structure of scientific communities. In this case we areinterested in how the information flow among scientists impacts theirdistribution of research across different rival hypotheses. Theimportance of scientific interaction for the production of scientificknowledge has traditionally been emphasized in social epistemology(Goldman 1999). But how exactly does the structure of communicationimpact scientists’ generation of knowledge? Are scientistsbetter off communicating within strongly connected social networks, orrather within less connected ones, and under which conditions ofinquiry? These and related questions belong to the field ofnetwork epistemology, which studies the impact ofcommunication networks on the process of knowledge acquisition.Network epistemology has its origin in economics, sociology andorganizational sciences (e.g., Granovetter 1973; Burt 1992; Jackson& Wolinsky 1996; Bala & Goyal 1998) and it was first combinedwith agent-based modeling in the philosophical literature by Zollman(2007) (see also Zollman 2013).

Simulations of scientific interaction originated in the idea thatdifferent communication networks among scientists, characterized byvarying degrees of connectedness (seeFigure 1), may have a different impact on the balance between“exploration” and “exploitation” of scientificideas. Suppose a scientist is trying to find an optimal treatment fora certain disease, since the existing one is insufficiently effective.On the one hand, she could pursue the currently dominant hypothesisconcerning the causes of the disease, hoping that it will eventuallylead to better results. On the other hand, she could explore novelideas hoping to have a breakthrough leading to a more successful curefor the disease. The scientist thus faces a trade-off betweenexploitation as the use of existing ideas and exploration as thesearch of new possibilities, long studied in theories of formallearning and in organizational sciences (March 1991). The informationflow among scientists could impact this trade-off in the followingway: if an initially misleading idea is shared too quickly throughoutthe community, scientists may lock-in on researching it, prematurelyabandoning the search for better solutions. Alternatively, if theinformation flow is slow and sparse, important insights gained by somescientists, which could lead to an optimal solution, may remainundetected by the rest of the community for a lengthy period of time.ABMs were introduced to investigate whether and in which circumstancesthe information flow could have either of these effects. For instance,if scientists are assumed to be rational agents, could a tightlyconnected community end up exploring too little and miss out onsignificant lines of inquiry?

Besides studying communities consisting of “epistemicallyuncompromised” scientists—that is, agents whose inquiryand actions are directed at discovering and promoting thetruth—similar questions can be posed about communities in whichepistemic interests have been overridden. For instance, the impact ofindustrial interest groups on science may lead to biased or deceptivepractices, which may sway the scientific community away from itsepistemic goals (Holman & Elliott 2018). While recentphilosophical discussions on this problem have largely focused on therole of non-epistemic values in science (Douglas 2009; Holman &Wilholt 2022; Bueter 2022; Peters 2021), ABMs were introduced toexamine how epistemically pernicious strategies can impact the processof inquiry, as well as to identify interventions that can be used tomitigate their harmful effects.

In addition to the problem of theoretical diversity, networkepistemology has been applied to a number of other themes, such asoptimal forms of collaboration, factors leading to scientificpolarization, effects of conformity on the collective inquiry, effectsof demographic diversity, the position of minorities, optimalregulations of dual-use research, argumentation dynamics, and soforth. We will look at the models studying theoretical diversity andthe communication structure of science inSection 4.2 andSection 4.6.

(a)

(b)

(c)

Figure 1: Three types of idealizedcommunication networks, representing an increasing degree ofconnectedness: (a) a cycle, (b) a wheel, and (c) a complete graph. Thenodes in each graph stand for scientists, while edges between thenodes stand for information channels between two scientists.

2.3 Cognitive diversity

A diversity of cognitive features of individuals can be beneficial invarious problem-solving situations, including business andpolicy-making (Page 2017). But how does the diversity of cognitivefeatures of scientists, including their background beliefs, reasoningstyles, research preferences, heuristics and strategies impact theinquiry of the scientific community? In philosophy of science, thisissue gained traction with Kuhn’s distinction between normal andrevolutionary science (Kuhn 1962), suggesting that differentpropensities may push scientists towards one type of research ratherthan another (see also Hull 1988). This raises the question: how doesthe distribution of risk-seeking, maverick scientists and risk-averseones impact the inquiry of the community? Put more generally: do someways of dividing labor across different research heuristics result ina more successful collective inquiry than others?

By equipping agents with different cognitive features we can use ABMsto represent different cognitively diverse (or uniform) populations,and to study their impact on some measure of success of the communalinquiry. We will look at the models studying these issues inSection 4.3.

2.4 Social diversity

A scientific community is socially diverse when its members endorsedifferent non-epistemic values, such as moral and political ones, orwhen they have different social locations, such as gender, race andother aspects of demography (Rolin 2019). The importance of socialdiversity has long been emphasized in feminist epistemology, both forethical and epistemic reasons. For instance, many have pointed outthat social diversity is an important catalyst for cognitivediversity, which in turn is vital for the diversity of perspectives,and therefore for scientific objectivity (Longino 1990, 2002; Haraway1989; Wylie 1992, 2002; Grasswick 2011; Anderson 1995; for adiscussion on different notions of diversity in the context ofscientific inquiry see Steel et al. 2018).

Moreover, in the field of social psychology and organizationalsciences, it has been argued that social diversity is epistemicallybeneficial even if it doesn’t promote cognitive diversity.Instead, it may counteract epistemically pernicious tendencies ofhomogeneous groups, such as unwarranted trust in each other’stestimony or unwillingness to share dissenting opinions (for anoverview of the literature see Page 2017; Fazelpour & Steel 2022).While these hypotheses have received support in virtue of empiricalstudies, ABMs have proved a complementary testing ground, allowing foran investigation of minimal sets of conditions which need to hold forsocial diversity to be epistemically beneficial.

Another problem tackled by means of ABMs concerns factors that canundermine social diversity or disadvantage members of minorities inscience. For instance, how does one’s minority status impactone’s position in a collaborative environment, given the normsof collaboration that can emerge in scientific communities? Or howdoes one’s social identity impact the uptake of their ideas? Wewill look at the models studying these issues inSection 4.4 andSection 4.7.

2.5 Peer-disagreement in science

Scientific disagreements are commonly considered vital for scientificprogress (Kuhn 1977; Longino 2002; Solomon 2006). They typically gohand in hand with theoretical diversity (seeSection 2.1 and2.2) and stimulate critical interaction among scientists, important forthe achievement of scientific objectivity. Nevertheless, an inadequateresponse to disagreements may lead to premature rejections of fruitfulinquiries, to fragmentation of scientific domains and hence toconsequences that are counterproductive for the progress of science.This raises the question: how should scientists respond todisagreements with their peers, to lower the chance of a hinderedinquiry? Which epistemic and methodological norms should they followin such situations?

This issue has been discussed in the context of the more generaldebate on peer-disagreement in social epistemology. The problem ofpeer disagreement concerns the question: what is an adequate doxasticattitude towardsp, upon recognizing that one’s peerdisagrees onp? Should one follow a “ConciliatoryNorm”, demanding, for instance, to lower the confidence inp, split the difference by taking the middle ground between theopponent’s belief and one’s own on the issue, or tosuspend one’s judgment onp? Or should one rather followa “Steadfast Norm” demanding to stick to one’s gunsand keep the same belief with the same confidence as beforeencountering a disagreeing peer? (For initial arguments in favor ofthe Conciliatory Norm see, e.g., Elga 2007, Christensen 2010, Feldman2006; for arguments in favor of the Steadfast Norm see, e.g., De Cruz& De Smedt 2013, Kelp & Douven 2012; for reasons why norms arecontext-dependent see, e.g., Kelly 2010 [2011], Konigsberg 2013,Christensen 2010, Douven 2010; for a recent critical review of thedebate as applied to scientific practice see Longino 2022.)

Similarly, in case of scientific disagreements and controversies wecan ask: should a scientist who is involved in a peer disagreementstrive towards weakening her stance by means of a conciliatory norm,or should she remain steadfast? What makes this issue particularlychallenging in the context of scientific inquiry is that we are notonly interested in the epistemic question of an adequate doxasticresponse to a disagreement, but also in the methodological (orinquisitive) question of how the norms impact the success ofcollective inquiry as a process. In particular, if scientistsencounter multiple disagreements throughout their research on acertain topic, will their collective inquiry benefit more fromindividuals adopting conciliatory attitudes or steadfast ones? ABMsnaturally lend themselves as a method for investigating these issues:by modeling scientists as guided by different normative responses to adisagreement, we can study the impact of the norms on the communalinquiry. We will look at the models studying these issues inSection 4.5.

2.6 Scientific polarization

Closely related to the issue of scientific disagreements is theproblem of scientific polarization. While scientific controversiestypically resolve over time, they may include periods of polarization,with different parts of the community maintaining mutually conflictingattitudes even after an extensive debate. But how and why doespolarization emerge? Do scientific communities polarize only ifscientists are too dogmatic or biased towards their viewpoints, or canpolarization emerge even among rational agents?

Following a range of formal models in social and political sciencesaddressing a similar issue in society at large (for a review seeBramson et al. 2017), ABMs have been used to examine the emergence ofpolarization in the context of science. What makes agent-basedmodeling particularly apt for this task is not only that we can modeldifferent aspects of individual inquiry that may contribute to theemergence of polarization (such as different background beliefs,different communication networks, different trust relationships, andso on), but we can also observe the formation of polarized states,their duration (as stable or temporary states throughout the inquiry)and their features (such as the distribution of scientists across theopposing views). We will look at the models studying these issues inSection 4.6.

2.7 Scientific collaboration

As acquiring and analyzing scientific evidence can be highlyresource-demanding for any individual scientist, scientificcollaboration is a widespread form of group inquiry. Of course, thisis not the only reason why scientists collaborate: incentives leadingto collaborations range from epistemic ones (such as increasing thequality of research) to non-epistemic ones (such as striving forrecognition). This raises the question: when is collaboratingbeneficial, and which challenges may occur in collaborative research?Inspired by these questions, philosophers of science have investigatedwhy collaborations are beneficial (Wray 2002), which challenges theypose on epistemic trust and accountability (Kukla 2012; Wagenknecht2015), what kind of knowledge emerges through collaborative research(such as collective beliefs or acceptances, (M. Gilbert 2000; Wray2007; Andersen 2010), which values are at stake in collaborations(Rolin 2015), what an optimal structure of collaborations is(Perović, Radovanović, Sikimić, & Berber 2016), andso on.

ABMs of collaboration were introduced to study the above and relatedquestions, focusing on how collaborating can impact inquiry. Whilecollaborations can indeed be beneficial, determining conditions underwhich they are such is not straightforward. For instance, depending onhow scientists engage in collaborations, minorities in the communitymay end up disadvantaged. We will look at the models studying theseissues inSection 4.7.

2.8 Summing up

Beside the above themes, ABMs have been applied to the study ofnumerous other topics in philosophy of science: from the allocation ofresearch funding, testimonial norms, strategic behavior of scientists,all the way to different procedures for theory-choice (seeSection 4.8 where we list models studying additional themes). Moreover, one ABMcan simultaneously address multiple questions (for example, socialdiversity and scientific collaboration are often inquiredtogether).

To study the questions presented in this section, philosophers haveutilized different representational frameworks. Even if models areaimed at the same research question, they are often based on differentmodeling approaches. For instance, individual scientists may berepresented as Bayesian reasoners, as agents with limited memory, asagents searching for peaks on an epistemic landscape, as agents thatform their opinions by averaging information they receive from otherscientists and from their own inquiry, or as agents that are equippedwith argumentative reasoning. Similarly, the process of evidencegathering may be represented in terms of pulls from probabilitydistributions, as foraging on an epistemic or an argumentationlandscape, or as receiving signals from others and from the world. Wenow look into some of the common modeling frameworks employed in thestudy of the above questions.

3. Common Modeling Frameworks

When developing a model examining certain aspects of scientificinquiry, one first has to decide on a number of relevantrepresentational assumptions, such as:

- How to represent the process ofinquiry andevidencegathering?

- What doagents in the simulation stand for (e.g.,individual scientists, research groups, scientific labs, etc.)?

- What are theunits of appraisal in scientific inquiry(e.g., hypotheses, theories, research programs, methods, etc.)?

- How do scientistsreason and evaluate their units ofappraisal?

- How do scientistsexchange information?

Similarly, if we wish to model a scenario in which scientists bargainabout the division of tasks or resources, we will have to decide howto represent theirinteractions andrewards they getout of them. These modeling choices are guided by the researchquestion the model aims to tackle, as well as the epistemic aim of themodel.

The majority of ABMs developed in philosophy of science are built assimple and highly idealized models. The simpler a model is, the easierit is to understand and analyze mechanisms behind the results ofsimulations (we return to this issue inSection 5). In this section, we delve into several common modeling frameworksthat have been used in this way. Each framework offers a differenttake on the above representational choices and has served as the basisfor a variety of ABMs. Particular models will not be discussed justyet—we leave this forSection 4.

3.1 Epistemic landscape models

Modeling the process of inquiry as an exploration of an epistemiclandscape draws its roots from models of fitness landscapes inevolutionary biology, first introduced by Sewall Wright (1932). Byrepresenting a genotype as a point on a multidimensional landscape,where the “height” of the landscape corresponds to itsfitness, the model has been used to study evolutionary paths ofpopulations.

The idea ofepistemic landscapes entered philosophy ofscience with the work of Weisberg and Muldoon (2009) and Grim (2009).In this reinterpretation of the model, the landscape represents aresearch topic, consisting of multiple projects or multiplehypotheses. A research topic can be understood either in a narrowsense (e.g., the study of treatments for a certain disease) or in abroader sense (e.g., the field of astrophysics). A point on thelandscape stands for a certain hypothesis or a specific approach toinvestigating the topic. Approaches can vary in terms of differentbackground assumptions, methods of inquiry, research questions, etc.Accordingly, the landscape can be modeled in terms of \(n\)dimensions, where \(n-1\) dimensions represent different aspects ofscientific approaches, while the \(n^{th}\) dimension (visualized asthe “height” of the landscape) stands for some measure ofepistemic value an agent gets by pursuing the corresponding approach.For instance, in case of a three-dimensional landscape, thexandy coordinates form a two-dimensional disciplinary matrix inwhich approaches are situated, whilez coordinate measurestheir “epistemic significance” (seeFigure 2). The latter can be understood in line with Kitcher’s idea thatsignificant approaches are those that enable the conceptual andexplanatory progress of science (Kitcher 1993: 95).

ABMs of science have utilized two-dimensional and three-dimensionallandscapes, as well as the generalized framework of NK-landscapes, inwhich the number of dimensions and the ruggedness of the landscape areparameters of the model.[1] Scientists are modeled as agents who explore the landscape, trying tofind its peak(s), that is, the epistemically most significant points.The framework allows for different ways of measuring the success andefficiency of inquiry: in terms of the success of the community indiscovering the peak(s) of the landscape (rather than getting stuck inlocal maxima), the success in discovering any of the areas of non-zerovicinity, the time required for such discoveries, and so forth.

Figure 2: Two representations ofWeisberg and Muldoon’s epistemic landscape: a three-dimensionalrepresentation on the left and a two-dimensional representation of thesame landscape on the right, where the height of the landscape isrepresented by different shades of gray: the lighter the shade, themore significant the point on the landscape (adapted from Weisberg& Muldoon 2009).

3.1.1 Application to the problem of cognitive diversity

The framework of epistemic landscapes has been applied to a variety ofresearch questions in philosophy of science. Weisberg and Muldoon(2009) introduced it to examine the impact of cognitive diversity onthe performance of scientific communities. What makes the epistemiclandscape framework particularly attractive for the study of cognitivediversity and the division of labor is its capacity to representvarious research strategies (as different heuristics of exploring thelandscape), as well as a coordinated distribution of research efforts(cf. Pöyhönen 2017).

Weisberg and Muldoon’s ABM employs a three-dimensional landscape(seeFigure 2), built on a discrete toroidal grid, with two peaks representing thehighest points of epistemic significance. To study cognitivediversity, the model examines three research strategies, implementedas three types of agents:

- The “controls” who aim to find a higher point on thelandscape than their current location, while ignoring the explorationof other agents.

- The “followers” who aim to find already exploredapproaches in their direct neighborhood, which have a highersignificance than their current location.

- The “mavericks” who also aim to find points of highersignificance given previously explored points, but rather thanfollowing in the footsteps of other scientists, they prioritize thediscovery of new, so far unvisited, points.

The control strategy represents individual learning that disregardssocial information, while the follower and the maverick strategiesrepresent different ways of taking the latter into account. The modelexamines how homogeneous populations of each type of explorers, orheterogeneous populations consisting of diverse groups of explorers,impact the efficiency of the community in discovering the highestpoints on the landscape, and in covering all points of non-zerosignificance.

Following Weisberg and Muldoon’s contribution, the framework ofepistemic landscapes became highly influential, resulting in variousrefinements and extensions of the model. For instance, Alexander,Himmelreich, and Thompson (2015) introduced the “swarm”strategy, which describes scientists who can with certain probabilityidentify points of higher significance in their surrounding and adjusttheir approach so that it is similar, but different from approachespursued by others who are close to them. Thoma (2015) introduced“explorer” and “extractor” strategies, theformer of which describes a scientist seeking approaches verydifferent from those pursued by others, while the latter (similar toAlexander and colleagues’ swarm researcher) seeks approachesthat are similar to, yet distinct from those pursued by others.Moreover, Fernández Pinto and Fernández Pinto (2018)examined alternative rules for the follower strategy. Finally,Pöyhönen (2017) introduced a “dynamic”landscape, such that the exploration of patches “depletes”their significance.

3.1.2 Applications to network epistemology

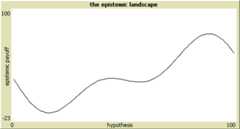

Another application domain of the epistemic landscape framework is thecommunication structure of science and its impact on communal inquiry.To study these issues Grim and Singer (Grim 2009; Grim, Singer,Fisher, et al. 2013) developed ABMs employing a two-dimensionallandscape, where points on thex-axis represent alternativehypotheses for a given domain of phenomena, while they-axisindicates the “epistemic goodness” of each hypothesis orthe epistemic payoff an agents gets by pursuing it. Depending on howwell the best hypothesis is hidden, the shape of the epistemic terrainwill represent a more or less “fiendish” research problem(seeFigure 3). For instance, if the best hypothesis is a narrow peak in thelandscape (as inFigure 3c) finding it will resemble a search for a needle in a haystack andtherefore a fiendish research problem.[2] An inquiry is considered successful if any scientist (eventuallyfollowed by the rest of the community) discovers the highest peak onthe landscape, while it is unsuccessful if the community converges ona local maximum. The model is used to study how different socialnetworks with varying degrees of connectedness (such as those inFigure 1), and different epistemic landscapes with different degrees offiendishness impact the success of inquiry.

(a)

(b)

(c)

Figure 3: Epistemic landscapes with anincreasing degree of fiendishness (adapted from Grim, Singer, Fisher,et al. 2013: 443)

3.1.3 Other applications

Beside the above themes, the framework of epistemic landscapes hasappeared in many other variants. For instance, De Langhe (2014a)proposed an ABM aimed at studying different notions of scientificprogress, which makes use of a “moving epistemiclandscape”: a landscape in which the significance of approachescan change as a result of exploration of other approaches. Balietti,Mäs, and Helbing (2015) developed an epistemic landscape model tostudy the relationship between fragmentation in scientific communitiesand scientific progress, in which agents explore a two-dimensionallandscape, representing a space of possible answers to a certainresearch question, with the correct answer located at the center ofthe landscape. Currie and Avin (2019) proposed a reinterpretation ofthe three-dimensional landscape aimed at studying the diversity ofscientific methods, in which thex andy axis stand fordifferent investigative techniques or methods of acquiring evidence,and thez axis for the “sharpness” of the obtainedevidence. Sharpness here refers to the relationship between researchresults and a hypothesis, where the more the evidence increasesone’s credence in the hypothesis, the sharper it is. The modelalso represents the “independence” of evidence as thedistance between two points on the landscape according to thexandy coordinates: the further apart two methods are, the lessoverlapping their background theories are, and the more independentthe evidence obtained by them is.

Finally, epistemic landscape modeling has inspired related landscapemodels. The argumentation-based model of scientific inquiry by Borg,Frey, Šešelja, and Straßer (2018, 2019) is onesuch example. The model, inspired by abstract argumentation frameworks(Dung 1995), employs an “argumentation landscape”. Thelandscape is composed of “argumentation trees” thatrepresent rival research programs (seeFigure 4). Each program is a rooted tree, with nodes as arguments and edges as a“discovery relation”, representing a path agents take tomove from one argument to another. Arguments in one theory may attackarguments in another theory. In contrast to epistemic landscapes,argumentation landscapes aim to capture the dialectic dimension ofinquiry where some points on the landscape, assumed to be acceptablearguments, may subsequently be rejected as undefendable. This allowsfor an explicit representation of false positives (accepting a falsehypothesis) as an argument on the landscape an agent accepts withoutknowing there exists an attack on it, and false negatives (rejecting atrue hypothesis) as an argument an agent rejects, without knowing thatit can be defended. The model has been used to study how argumentativedynamics among scientists, pursuing rival research programs, impactstheir efficiency in acquiring knowledge under various conditions ofinquiry (such as different social networks, different degrees ofcautiousness in decision making, and so on).

Figure 4: Argumentation-based ABM byBorg, Frey, Šešelja, and Straßer (2019) employingan argumentative landscape. The landscape represents two rivalresearch programs (RP), with darker shaded nodes standing forarguments that have been explored by agents and are thus visible tothem; brighter shaded nodes stand for arguments that are not visibleto agents. The biggest node in each RP is the root argument, fromwhich agents start their exploration via the discovery relation,connecting arguments within one RP. Arrows stand for attacks from anargument in one RP to an argument in another RP.

3.2 Bandit models

In the previous section we saw how epistemic landscape models havebeen used to represent inquiries involving mutually compatibleresearch projects (as in Weisberg and Muldoon’s model) as wellas inquiries involving rival hypotheses (as in Grim and Singer’smodel). Another framework used to study the latter scenario is basedon “bandit problems”.

The name of bandit models comes from the term “one-armedbandit”—a colloquial name for a slot machine. Multi-armedbandit problems, introduced in statistics (Robbins 1952; Berry &Fristedt 1985) and studied in economics (Bala & Goyal 1998; Bolton& Harris 1999), are decision-making problems that concern thefollowing kind of scenario: suppose a gambler is about to play severalslot machines. Each machine gives a random payoff according to aprobability distribution unknown to the gambler. To determine whichmachine will give a higher reward in the long run, the gambler has toexperiment by pulling arms of the machines. This will allow her tolearn from the obtained results. But which strategy should she use?For instance, should she alternate between the machines for the firstcouple of pulls, and then play only the machine that has given thehighest reward during the initial test run? Or should she rather havea lengthy test phase before deciding which machine is better? While inthe first case she might startexploiting her currentknowledge before she has sufficientlyexplored, in the secondcase she might explore for too long. In this way the gambler faces atrade-off between exploitation (playing the machine that has so fargiven the best payoff) and exploration (continued testing of differentmachines). The challenge is thus to come up with the strategy thatprovides an optimal balance between exploration and exploitation, soas to maximize one’s total winnings.

As we have seen above (seeSection 2.2), the exploration/exploitation trade-off may also occur in the contextof scientific research. Whether scientists are attempting to determineif a novel treatment for a disease is superior to an existing one, orselecting between two novel methods of evidence gathering with varyingsuccess rates, they may encounter the exploration/exploitationtrade-off. In other words, they may have to decide when to ceaseexploring alternatives and begin exploiting the one that appears mostsuitable for the task.

ABMs based on bandit problems were first introduced to philosophy ofscience by Zollman (2007, 2010). A bandit ABM usually looks asfollows. In analogy to slot machines, each scientific theory (orhypothesis, or method) is represented as having a designatedprobability of success. Scientists are typically modeled as“myopic” agents in the sense that they always pursue atheory they believe to give a higher payoff. They gather evidence fora theory by making a random draw from a probability distribution.Subsequently, they update their beliefs in a Bayesian way, on thebasis of results of their own research (the gathered evidence) as wellas results of neighboring scientists in their social network (such asthose inFigure 1). Scientists are thus not modeled as passive observers of evidence forall the available theories, but rather as agents who activelydetermine the type of evidence they gather by choosing which theory topursue. The inquiry of the community is considered successful if, forexample, scientists reach a consensus on the better of the twotheories.

Bandit models of this kind build on the analytical framework developedby economists (Bala & Goyal 1998) who examined the relationshipbetween different communication networks in infinite populations andthe process of social learning. Applied to the context of science,this variation of bandit problems concerns the puzzle mentioned aboveinSection 2.2: assuming a scientific community is trying to determine which of thetwo available hypotheses offers a better treatment for a givendisease, could the structure of the information flow among thescientists impact their chances of converging on the betterhypothesis? By applying Bala and Goyal’s framework to thecontext of science and scenarios involving finite populations, Zollmaninitiated the field of network epistemology (see Zollman 2013), whichstudies the impact of social networks on the process of knowledgeacquisition.

Beside the aim of examining network effects on the formation ofscientific consensus, bandit models of scientific interaction havebeen applied to a number of other topics, such as the impact ofpreferential attachment on social learning (Alexander 2013), bias anddeception in science (Holman & Bruner 2015, 2017; Weatherall,O’Connor, & Bruner 2020), optimal forms of collaboration(Zollman 2017), factors leading to scientific polarization(O’Connor & Weatherall 2018; Weatherall & O’Connor2021b), effects of conformity (Weatherall & O’Connor 2021a),effects of demographic diversity (Fazelpour & Steel 2022),regulations of dual-use research (Wagner & Herington 2021), sociallearning in which a dominant group ignores or devalues testimony froma marginalized group (Wu 2023), or disagreements on the diagnosticityof evidence for a certain hypothesis (Michelini & Osorio et al.forthcoming).

3.3 Bounded confidence models of opinion dynamics

As we have seen above, the performance of a scientific community issometimes assessed in terms of its success in achieving consensus onthe true hypothesis. The question how consensus is formed and whichfactors benefit or hinder its emergence is also studied within thetheme ofopinion dynamics in epistemic communities. Models ofopinion dynamics aim at investigating how opinions form and change ina group of agents who adjust their views (or beliefs) over a number ofrounds or time-steps, resulting in the formation ofconsensus,polarization, or aplurality ofviews. A modeling framework that has been particularly influential inthis context originates from the work of Hegselmann and Krause (2002,2005, 2006), drawing its roots from analytical models of consensusformation (French 1956; DeGroot 1974; Lehrer & Wagner 1981).[3]

The basic model functions as follows. At the start of the simulation(that is, at time \(t=0\)) each agent \(x_i\) is assigned an opinionon a certain issue, expressed by a real number \(x_i(0) \in {(0,1]}\).Agents then exchange their opinions (or beliefs) with others andadjust them by taking the average of those beliefs that are “nottoo far away” from their own. These are opinions that fallwithin a “confidence interval” of size \(\epsilon\), whichis a parameter of the model. In this way, agents have boundedconfidence in opinions of others. By iterating this process, the modelsimulates the social dynamics of the opinion formation (seeFigure 5a).

Applied to the context of scientific inquiry, scientists are usuallyrepresented as truth seeking agents who are trying to determine thevalue of a certain parameter \(\tau\) for which they only know that itlies in the interval \((0,1]\) (Hegselmann & Krause 2006). At thestart of the simulation each agent is assigned a random initialbelief. As the model runs, agents adjust their beliefs by receiving a(noisy) signal about \(\tau\) and by learning opinions of others whofall within their confidence interval. For instance, an agent’sbelief can be updated in terms of the weighted average ofothers’ opinions and the signal from the world.[4] Such dynamics represent scientists as agents who are able to generateevidence that points in the direction of \(\tau\), though theirupdates are also influenced by their prior beliefs and the beliefs oftheir peers (seeFigure 5b &Figure 5c).

(a)

(b)

(c)

Figure 5: Examples of runs of Hegselmannand Krause’s model, with thex-axis representing timesteps in the simulation and they-axis opinions of 100 agents.The change of each agent’s opinion is represented with a coloredline. The value of \(\tau\) (the assumed position of the truth) isrepresented as a black dotted line. Figure (a) shows opinion dynamicsin a community without any truth-seeking agents, resulting in aplurality of diverging views. Figure (b) shows the opinion dynamics ina community in which all agents are truth-seekers, which achieves aconsensus close to the truth. Figure (c) shows the opinion dynamics ina community in which only half of the population are truth-seekers,which also achieves a consensus close to the truth (adapted fromHegselmann & Krause 2006; for other parameters used in thesimulations see the original article).

An early application of the bounded confidence model was the problemof the division of cognitive labor (Hegselmann & Krause 2006).Since agents can be modeled as updating their beliefs only on thebasis of social information (that is, by averaging over opinions ofothers who fall in one’s confidence interval) or on the basis ofboth social information and the signal from the world, the model canbe used to study the opinion dynamics in a community in which noteveryone is a “truth-seeker”. The model then examines whatkind of division of labor between truth-seekers and agents who onlyreceive social information allows the community to converge to thetruth.

Subsequent applications of the framework in social epistemology andphilosophy of science focused on the study of scientific disagreementsand the question: what is the impact of different norms guidingdisagreeing scientists on the efficiency of collective inquiry (Douven2010; De Langhe 2013)? If agents update their beliefs both in view oftheir own research and in view of other agents’ opinions theyrepresent scientists that follow a Conciliatory Norm by“splitting the difference” between their own view and theviews of their peers (see aboveSection 2.5). In contrast, if they update their beliefs only in view of their ownresearch they represent scientists that follow a Steadfast Norm. Otherapplication themes of this framework include the impact of noisy dataon opinion dynamics (Douven & Riegler 2010), opinion dynamicsconcerning complex belief states, such as beliefs about scientifictheories (Riegler & Douven 2009), updating via an inference to thebest explanation in a social setting (Douven & Wenmackers 2017),deceit and spread of disinformation (Douven & Hegselmann 2021),network effects and theoretical diversity in scientific communities(Douven & Hegselmann 2022), and so forth.

3.4 Evolutionary game-theoretic models of bargaining

Game theory studies situations in which the outcome of one’saction depends not only on one’s choice of an action, but alsoon actions of others. A “game” in this sense is a model ofa strategic interaction between agents (“players”), eachof whom has a set of available actions or strategies. Each combinationof the players’ strategic responses has a designated outcome ora “payoff”. In contrast to traditional game theory, whichfocuses on agents’ rational decision-making aimed at maximizingtheir payoff in one-off interactions, the evolutionary approachfocuses on repeated interactions in a population. A game is assumed tobe played over and over again by players who are randomly drawn from alarge population. While agents start with a certain strategicbehavior, they learn and gradually adjust their responses according tospecific rules called “dynamics” (for example, byimitating other players or by considering their own pastinteractions). As a result, successful strategies will diffuse acrossthe community. In this way, evolutionary game-theoretic models can beused to explain how a distribution of strategies across the populationchanges over time as an outcome of long-term population-levelprocesses. While the standard approach to game theory has primarilyfocused on combinations of players’ strategies that lead to a“stable” state, such as the Nash equilibrium—a statein which no player can improve their payoff by unilaterally changingtheir strategy—the evolutionary approach has been used to studyhow equilibria emerge in a community (see the entries ongame theory and onevolutionary game theory).

Evolutionary game theory was originally introduced in biology(Lewontin 1961; Maynard Smith 1982). It subsequently gained interestof social scientists and philosophers as a tool for studying culturalevolution, that is, for investigations into how beliefs and normschange over time (Axelrod 1984; Skyrms 1996). The models can beimplemented using a mathematical treatment based on differentialequations, or using agent-based modeling. While the former approachemploys certain idealizations, such as an infinite population size orperfect mixing of populations, ABMs were introduced to study scenariosin which such assumptions are relaxed (see, e.g., Adami, Schossau,& Hintze 2016).

Applications of evolutionary game theory to social epistemology ofscience were especially inspired by models of bargaining, studying howdifferent bargaining norms emerge from local interactions ofindividuals (Skyrms 1996; Axtell, Epstein, & Young 2001). Theframework was introduced to the study of epistemic communities byO’Connor and Bruner (2019), building up on Bruner’s (2019)model of cultural interactions.[5]

The basic idea of bargaining models is as follows: agents bargain overshares of available resources, where their demands and expectationsabout others’ demands evolve endogenously in view of theirprevious interactions. Applied to the context of science, bargainingconcerns not only explicit negotiations over financial resources, butalso situations in which scientists need to agree how to divide theirworkload in joint projects (O’Connor & Bruner 2019). Forexample, if two scientists are working on a joint paper or if they areorganizing a conference together they will have to agree on how muchtime and effort each of them will devote to it. The norms determiningsuch a division of labor may not be fair. For example, if scientistA puts much less effort into the project than scientistB, but they both get the same recognition for its success,B will be disadvantaged. Similarly, if they agree onAbeing the first author in a collaborative paper, whileB endsup working much more on it, the outcome will again be unfair. Suchnorms may become entrenched in the scientific community, especially inthe context of interactions between members of majority and minoritygroups in academia. But how do such norms emerge? Are biases favoringmembers of certain groups over others necessary for the emergence ofsuch discriminatory patterns, or can they become entrenched due toother, perhaps more surprising factors?

Evolutionary game-theoretic models have been used to study these andrelated questions. Bargaining is represented as a strategicinteraction between two agents, each of whom makes a demand concerningthe issue at hand (for instance, a certain amount of workload, theorder of authors’ names in a joint publication, and so on).Depending on each agent’s demand, each gets a certain payoff.For instance, supposeA andB wish to organize aconference and they start by negotiating who will cover which tasks.If they both make a high demand in the sense that each is willing toput only a minimal effort into the project while expecting the otherto cover the rest of the tasks, they will fail to organize the event.IfB, on the other hand, makes a low demand (by taking on alarger portion of the work) whileA makes a high demand, theywill be able to organize the conference, though the division of laborwill be unfair (assuming they both get equal credit for successfullyrealizing the project).

The game, originating in the work of John Nash (1950), is called the“Nash demand game” (or the “mini-Nash demandgame”). Each player in the game makes their demand (Low, Med orHigh). If the demands do not jointly exceed a given resource, eachplayer gets what they asked for. If they do exceed the availableresource, no-one gets anything. In the example above, High can beinterpreted as demanding to work less than the other on theorganization of the conference, or demanding the first authorship in ajoint paper while putting relatively lower effort into it. Similarly,Low corresponds to the willingness to take on a larger portion of thework (relative to the order of authors in case of the joint paper),while Med corresponds to demanding a fair distribution of labor.Table 1 displays the payoffs in such a game. Any combination of demands thatgives a joint payoff of 10 is a Nash equilibrium, which means thateither player’s strategy is the best response to the otherplayer’s one. While a Nash equilibrium may correspond to a fairdistribution of resources (if both players demand Med), it may alsocorrespond to an unfair one (if one player demands Low and the otherone High). This raises the question: which equilibrium will thecommunity achieve if agents learn from their previous interactions? Inparticular, if the individuals are divided into sub-groups (which maybe of different sizes), where their membership can be identified bymeans of markers visible to other agents, they can develop strategiesconditional on the group membership of their co-players. Whichequilibrium state will such a community evolve to? To study suchquestions, evolutionary models employ rules or dynamics that determinehow players update their strategies and how the distribution ofstrategies across the community changes over time.[6]

| Low | Med | High | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | L,L | L,5 | L,H |

| Med | 5,L | 5,5 | 0,0 |

| High | H,L | 0,0 | 0,0 |

Table 1: A payoff table in the Nashdemand game. The rows show the strategic options of Player1 and thecolumns the options of Player2. Each cell shows the payoff Player1gets for the given combination of options, followed by the payoff forPlayer2. Players can make three demands: Low, Med and High for thetotal resource of 10. The payoffs are represented as L, M and H, where\(\mathrm{M}= 5\), \(\mathrm{L} < 5 < \mathrm{H}\), and\(\mathrm{L} + \mathrm{H} = 10\). (cf. O’Connor & Bruner2019; Rubin & O’Connor 2018)

The modeling framework based on bargaining has been used to studynorms in scientific collaborations and inequalities that may emergethrough them. For example, O’Connor and Bruner (2019)investigate the emergence of discriminatory norms in academicinteractions between minority and majority members. Rubin andO’Connor (2018) study the emergence of discriminatory patternsand their effects on diversity in collaboration networks, whileVentura (2023) examines the impact of the structure of collaborativenetworks on the emergence of discriminatory norms even if there are novisible markers of an agent’s membership to a sub-group.Moreover, Klein, Marx, and Scheller (2020) use a similar framework tostudy the relationship between rationality and inequality, that is,the success of different strategies for bargaining (such as maximizingexpected utility) and their impact on the emergence of inequality.

3.5 Summing up

Besides the above frameworks, numerous additional approaches have beenused to build simulations in social epistemology and philosophy ofscience. Some prominent frameworks not mentioned above include theBayesian framework “Laputa” developed by Angere(2010—in Other Internet Resources) and Olsson (2011), aimed atstudying social networks of information and trust, the model ofargumentation dynamics by Betz (2013), or the influential framework byHong and Page (2004) utilized in the study of cognitive diversity (formore on these frameworks see the entry oncomputational philosophy). Another evolutionary framework used in philosophy of science wasproposed by Smaldino and McElreath (2016). The model represents ascientific community as a population consisting of scientific labsthat employ culturally transmitted methodological practices, where thepractices undergo natural selection from one generation of scientiststo the next, and it has been employed, for example, to study theselection of conservative and risk-taking science (O’Connor2019). In the next section we take a look at some of the centralresults obtained by ABMs in philosophy of science, based on the aboveand some other frameworks.

4. Central Results

To provide an overview of the main findings obtained by means of ABMsin philosophy of science, we will revisit the research questionsdiscussed inSection 2 and look at how they have been answered through specific models.

4.1 Theoretical diversity and the incentive structure of science

Before we survey ABMs that study the incentive structure of science,we first look into the results of some analytical models whichinspired the development of simulations. To get a more precise grip onhow individual incentives shape epistemic coordination and theoreticaldiversity, philosophers introduced formal analytical models, inspiredby research in economics. One of the central results from this body ofliterature is that the optimal distribution of labor can be achievedwhen scientists act according to their self-interest rather thanfollowing epistemic ends (e.g., Kitcher 1990; Brock & Durlauf1999; Strevens 2003). More precisely, the models show that if weassume scientists aim at maximizing rewards from making discoveries,they will succeed to optimally distribute their research efforts ifthey take into account the probability of success of each researchline and how many other scientists currently pursue it. Assuming thatall scientists evaluate theories in the same way, their interest infame and fortune, rather than epistemic goals alone, will lead some ofthem to select avenues that initially appear less promising.[7]

ABMs were introduced to address similar questions, but assuming morecomplex scenarios. For example, Muldoon and Weisberg (2011) developedan epistemic landscape model (seeSection 3.1) to examine the robustness of Kitcher’s and Strevens’results under the assumption that scientists have varying access toinformation about the pursued research projects in their community andthe future success of those projects. Their results indicate that oncescientists have limited information about what others are working on,or about the degree to which projects are likely to succeed, theirself-organized division of labor fails to be optimal. Another exampleis the model by De Langhe & Greiff (2010) who generalizeKitcher’s model to a situation with multiple epistemic standardsdetermining the background assumptions of scientists, acceptablemethods, acceptable puzzles, and so on. The simulations show that oncescientific practice is modeled as based on multiple standards, theincentive to compete fails to provide an optimal division of labor.

A closely related question concerns the “priorityrule”—a norm that allocates credit for a scientificdiscovery to the first one to make it (Strevens 2003, 2011)—andits impact on the division of labor. While Kitcher’s andStrevens’s models suggested that the priority rule incentivizesthe optimal distribution of scientists across rival research programs,a range of formal models, including ABMs, were developed to reexaminethese results and shed additional light on this norm. For instance,Rubin and Schneider (2021) examine what happens if credit is assignedby individuals, rather than by the scientific community as a whole, asin Strevens’ model. They further suppose that news aboutsimultaneous discoveries by two scientists spreads through a networkedcommunity. The simulations show that more connected scientists aremore likely to gain credit than the less connected ones, which may, onthe one hand, disadvantage minority members in the community, and onthe other hand, undermine the role of the priority rule as anincentive resulting in the optimal division of labor. Besides thequestion of how the priority rule impacts the division of labor, ABMshave also been used to study other effects of the priority rule. Forexample, Tiokhin, Yan, and Morgan (2021) develop an evolutionary ABMshowing that the priority rule leads the scientific community toevolve towards research based on smaller sample sizes, which in turnreduces the reliability of published findings.

The impact of incentives on the division of labor in science has alsobeen analyzed in terms of incentives to “exploit” existingprojects in contrast to incentives to “explore” novelideas. For instance, De Langhe (2014b) developed a generalized versionof Kitcher and Strevens’ model in which agents achieve theoptimal division of labor by weighing up relative costs and benefitsof exploiting available theories and exploring new ones. Within theframework of bandit models and network epistemology (seeSection 3.2), Kummerfeld and Zollman (2016) proposed an ABM that examines ascenario in which scientists face two rival hypotheses, one of whichis better though the agents don’t know which one. While agentsalways choose to pursue (or exploit) a hypothesis that seems morepromising, they may also occasionally research (and thereby explore)the alternative one. The simulations show that if the community isleft to be self-organized in the sense that each scientist explores tothe extent that they consider individually optimal, agents will beincentivized to leave exploration to others. As a result, scientistswill fail to develop a sufficiently high incentive for exploring novelideas, that is, an incentive which would be optimal from theperspective of their community at large.

4.2 Theoretical diversity and the communication structure of science

4.2.1 The “Zollman effect”

The study of theoretical diversity in terms of network epistemologyled to a novel hypothesis: that the communication structure of ascientific community can promote or hinder the emergence oftheoretical diversity and thereby impact the division of cognitivelabor. The idea was first demonstrated by bandit models developed byZollman (2007, 2010; seeSection 3.2) and came to be known as the “Zollman effect” (Rosenstock,Bruner, & O’Connor 2017). ABMs by Grim (2009) Grim, Singer,Fisher, and colleagues (2013), and Angere & Olsson (2017) producedsimilar findings based on different modeling frameworks.[8] These models show that in highly connected communities earlyerroneous results may spread quickly among scientists, leading them toinvestigate a sub-optimal line of inquiry. As a result, scientists mayprematurely abandon the exploration of different hypotheses, andinstead exploit the inferior ones. In light of these findings, Zollman(2010) emphasized that for an inquiry to be successful it needs aproperty of “transient diversity”: a process in which acommunity engages in a parallel exploration of different theories,which lasts sufficiently long to prevent a premature abandonment ofthe best theory, but which eventually gets replaced by a consensus onit. Besides the result that connectivity can be harmful, it has alsobeen shown that learning in less connected networks is slower, whichindicates a trade-off between accuracy and speed in the context ofsocial learning (Zollman 2007; Grim, Singer, Fisher, et al. 2013).

Subsequent studies showed, however, that the Zollman effect is notvery robust within the parameter space of the original model(Rosenstock et al. 2017). In particular, the result holds for thoseparameters that can be considered characteristic of difficult inquiry:scenarios in which there is a relatively small number of scientists,the evidence is gathered in relatively small batches, and thedifference between the objective success of the rival hypotheses isrelatively small. Moreover, additional models showed that if thediversity (and hence, exploration) of pursued hypotheses is generatedin some other way, more connected communities may outperform lessconnected ones. For instance, Kummerfeld and Zollman (2016) showedthat relaxing the trade-off between exploration and exploitation byallowing agents to occasionally gain information about the hypothesisthey are not currently pursuing is a way to generate diversity,leading a fully connected community to perform better than lessconnected ones. Another way of generating diversity was examined byFrey and Šešelja (2020): they show that if scientistshave a dose of caution or “rational inertia” when decidingwhether to abandon their current theory and start pursuing the rival,a fully connected community gets a sufficient degree of exploration tooutperform less connected groups. Similar points have been made withABMs based on other modeling frameworks, such as the boundedconfidence model by Douven and Hegselmann (2022), or anargumentation-based ABM by Borg, Frey, Šešelja, andStraßer (2018), each of which shows a different way ofpreserving transient diversity in spite of a high degree ofconnectivity.

4.2.2 The spread of disinformation

ABMs studying epistemically pernicious strategies in scientificcommunities have largely employed network epistemology bandit models(seeSection 3.2). For instance, a model by Holman and Bruner (2015) examines how aninterference of industry-sponsored agents may impact the informationflow in the medical community, and which strategies scientists couldemploy to protect themselves from such a pernicious influence. Forthis purpose, they consider a scenario in which medical doctorsregularly communicate with industry-sponsored agents about theefficacy of a certain pharmaceutical product as a treatment for agiven disease. Since the industry-sponsored agents are motivated byfinancial rather than epistemic interests and they are unlikely tochange their minds no matter how much opposing evidence they receive,they are not merely biased, but “intransigently biased”.Their simulations indicate two ways in which a scientific communitycan protect itself from the pernicious influence of the intransigentlybiased agent: first, by increasing their connectivity, and second, bylearning how to reorganize their social network on the basis oftrustworthiness, which leads them to eventually ignore the biasedagent. In a follow-up model, Holman and Bruner (2017) also show howthe industry can bias a scientific community without corrupting any ofthe individual scientists that compose it, but by simply helpingindustry-friendly scientists to have successful careers.

Using a similar network-epistemology approach, Weatherall,O’Connor and Bruner (2020) developed a bandit model to study the“Tobacco strategy”, employed by the tobacco industry inthe second half of the twentieth century to mislead the public aboutthe negative health effects of smoking (analyzed in detail by Oreskes& Conway 2010). In particular, the model examines how certaindeceptive practices can mislead public opinion without eveninterfering with (epistemically driven) scientific research. Theauthors look into two such propagandist strategies: a “selectivesharing” of research results that fit the industry’spreferred position, and a “biased production” of researchresults where additional research gets funded, but only suitablefindings get published. The results show that both strategies areeffective in misleading policymakers about the scientific output undervarious examined parameters since in both cases the policymakersupdate their beliefs on the basis of a biased sample of results,skewed towards the worse theory. The authors also look into strategiesemployed by journalists reporting on scientific findings and show thatincautiously aiming to be “fair” by reporting an equalnumber of results from both sides of the controversy may result in thespread of misleading information.

Another example of ABMs developed to examine deception in science isan argumentation-based model by Borg, Frey, Šešelja, andStraßer (2017, 2018; seeSection 3.1.3). Assuming the context of rival research programs where scientists haveto identify the best out of three available ones, deceptivecommunication is represented in terms of agents sharing only positivefindings about their theory, while withholding news about potentialanomalies. The underlying idea is that deception consists in providingsome (true) information while at the same time withholding otherinformation, which leads the receiver to make a wrong inference(Caminada 2009). Unlike the previous two models discussed in thissection, where not all agents display biased or deceptive behavior,Borg et al. study network effects in a population consisting entirelyof deceptive scientists. Such a scenario represents a community thatis driven, for instance, by confirmation bias and an incentive toshield one’s research line from critical scrutiny. Thesimulations show that, first, reliable communities (consisting of nodeceivers) are significantly more successful than the deceptive ones,and second, increasing the connectivity makes it more likely thatdeceptive populations converge on the best theory.

4.3 Cognitive diversity

As we have seen inSection 2.1, the problem of cognitive diversity concerns the relation between thediversity of cognitive features of scientists (including theirbackground beliefs, reasoning styles, research preferences, heuristicsand strategies) and the inquiry of the scientific community.Philosophers of science have especially been interested in how thedivision of labor across different research heuristics impacts theperformance of the community.

A particularly influential ABM tackling this issue is the epistemiclandscape model by Weisberg and Muldoon (2009). The model examines thedivision of labor catalyzed by different research strategies, wherescientists can act as the “controls”,“followers” or “mavericks” (see aboveSection 3.1). In view of the simulations, Weisberg and Muldoon argue that, first,mavericks outperform other research strategies. Second, if we considerthe maverick strategy to be costly in terms of the necessaryresources, then introducing mavericks to populations of followers canlead to an optimal division of labor. While Weisberg andMuldoon’s ABM eventually turned out to include a coding error(Alexander et al. 2015), their claim that cognitive diversity improvesthe productivity of scientists received support from adjusted versionsof the model, albeit with some qualifications.

First, Thoma’s (2015) model showed that cognitively diversegroups outperform homogeneous ones if scientists are sufficientlyflexible to change their current approach and sufficiently informedabout the research conducted by others in the community. Second,Pöyhönen (2017) confirmed that if we consider the maverickstrategy to be slightly more time-consuming, mixed populations ofmavericks and followers may outperform communities consisting only ofmavericks in terms of the average epistemic significance of theobtained results. According to Pöyhönen, another conditionthat needs to be satisfied if cognitive diversity is to be beneficialconcerns the topology of the landscape: diverse populations outperformhomogeneous ones only in case of more challenging inquiries(represented in terms of rugged epistemic landscapes), but not in caseof easy research problems (represented by landscapes such as Weisbergand Muldoon’s one,Figure 2). The importance of the topology of the landscape was also emphasizedby Alexander and colleagues (2015) who use NK-landscapes to show thatwhether social learning is beneficial or not crucially depends on thelandscape’s topology. Finally, there are other researchstrategies (such as Alexander and colleagues’“swarm” one, seeSection 3.1.1) that outperform Weisberg and Muldoon’s mavericks, while smallchanges in the follower strategy may significantly improve itsperformance (Fernández Pinto & Fernández Pinto2018).

Another aspect of cognitive diversity that received attention in themodeling literature concerns the relationship between diversity andexpertise. This issue was first studied in economics by Hong and Page(2004). The model examined how heuristically diverse groups,consisting of agents with diverse problem-solving approaches, comparewith groups consisting solely of experts with respect to finding asolution to a particular problem. Hong and Page’s originalresult suggested that “diversity trumps ability” in thesense that groups consisting of individuals employing diverseheuristic approaches outperfom groups consisting solely of experts,that is, agents who are the best “problem-solvers”. Whilethis finding became quite influential, subsequent studies showed thatit does not hold robustly once more realistic assumptions aboutexpertise are added to the model (Grim, Singer, Bramson, et al. 2019;Reijula & Kuorikoski 2021; see also Singer 2019).

The problem of cognitive diversity and the division of labor inscientific communities was also studied by Hegselmann andKrause’s bounded-confidence model (Hegselmann & Krause 2006;see aboveSection 3.3). The ABM examines opinion dynamics in a community that is diverse inthe sense that only some individuals are active truth seekers, whileothers adjust their beliefs by exchanging opinions with those agentswho have sufficiently similar beliefs to their own. Hegselmann andKrause investigate conditions under which such a community can reachconsensus on the truth, combining agent-based modeling and analyticalmethods. They show that, on the one hand, if all agents in the modelare truth seekers, they achieve a consensus on the truth. On the otherhand, if the community divides labor, its ability to reach a consensuson the truth will depend on the number of truth seeking agents, theposition of the truth relative to the agents’ opinions, thedegree of confidence determining the scope of opinion exchange and therelative weight of the truth signal (in contrast to the weight ofsocial information). For instance, under certain parameter settingseven a single truth-seeking agent will lead the rest of the communityto the truth.

4.4 Social diversity

As we have seen inSection 2.4, ABMs were introduced to study two issues that concern socialdiversity in the context of science: first, epistemic effects ofsocially diverse scientific groups, and second, factors that canundermine social diversity or disadvantage members of minorities inscience.