Structured Propositions

It is a truism that two speakers can say the same thing by utteringdifferent sentences, whether in the same or different languages. Forexample, when a German speaker utters the sentence ‘Schnee istweiss’ and an English speaker utters the sentence ‘Snow iswhite’, they have said the same thing by uttering the sentencesthey did. Proponents of propositions hold that, speaking strictly,when speakers say the same thing by means of different declarativesentences, there is some (non-linguistic) thing, a proposition, thateach has said.[1] This proposition is said to be expressed by both of the sentencesuttered (taken in the contexts of utterance—to accommodatecontextually sensitive expressions) by the speakers, and can bethought of as the information content of the sentences (taken in thosecontexts). The proposition is taken to be the thing that is in thefirst instance true or false. A declarative sentence is true or falsederivatively, in virtue of expressing (in the context in which it isuttered—this contextual sensitivity shall henceforth be ignoredand so qualifications of this sort dispensed with) a true or falseproposition.

Propositions are thought to perform a number of other functions inaddition to being the bearers of truth and falsity and the thingsexpressed by declarative sentences. When a German and English speakerbelieve the same thing, say that the earth is round, the thing theyboth believe is not a sentence but a proposition. For the Englishspeaker would express her belief by means of the sentence ‘Theearth is round’ and the German speaker would express her beliefby means of the different sentence ‘Die Erde ist rund’.Thus when people believe, doubt and know things, it is propositionsthat they bear these cognitive relations to. Finally, it is theproposition a sentence expresses, and not the sentence itself, thatpossesses modal properties such as being necessary, possible orcontingent.

That propositions perform these various functions is agreed upon byvirtually all advocates of propositions.[2] There is considerably less agreement concerning the nature of thethings, propositions, that perform these functions.[3]

To say that propositions are structured is to say something about thenature of propositions. Roughly, to say that propositions arestructured is to say that they are complex entities, entities havingparts or constituents, where the constituents are bound together in acertain way. Thus, particular accounts of structured propositions can(and do) differ in at least two ways: 1) they can differ as to whatsorts of things are the constituents of structured propositions; and2) they can differ as to what binds these constituents together in aproposition. Various accounts of structured propositions that differin these ways will be discussed below.

Put this way, the view that propositions are structured is purely ametaphysical thesis about what propositions are like and entailsnothing about the relation between a sentence and the proposition itexpresses. But of course structured proposition theorists do haveviews about the relation between a sentence and the proposition itexpresses.

- 1. Setting Up the Problems

- 2. From Possible Worlds to Structured Propositions

- 3. Some Recent Accounts of Structured Propositions

- 4. Historical Antecedents to Current Views: Frege

- 5. Historical Antecedents to Current Views: Russell

- Bibliography

- Academic Tools

- Other Internet Resources

- Related Entries

1. Setting Up the Problems

Intuitively, given that a sentence expresses a structured proposition,the proposition will have parts or constituents that are the semanticvalues of words or subsentential complex linguistic expressionsoccurring in the sentence; and the proposition will have a structuresimilar to the structure of the sentence. For example, assuming thatthe semantic value of a name is its bearer and that the semantic valueof a transitive verb is a relation, a structured proposition theoristwill likely hold that the sentence

- (1)Jason lovesPatty

expresses a proposition consisting of Jason, the loving relation andPatty, bound together in some way into a unity. Letting‘j’ stand for Jason, ‘p’ forPatty and ‘L’ for the loving relation, we canrepresent the proposition in question as follows:

- (1a)[j[L[p]]]

Thus (1a)’s structure is very close to that of (1); and (1a) hasas constituents the semantic values of the words occurring in (1).Indeed, in the case of (1) and (1a), all and only semantic values ofwords in the sentence are constituents of the proposition. But a givenaccount of structured propositions may not hold that this is the casein general for any one of at least three reasons. First, one mighthold that certain words as they occur in phrases in sentences do notcontribute their semantic values to the propositions expressed bythose sentences because the semantic values of these words insteadpartially determine the semantic values of the phrases in which theyoccur, where these latter semantic values are contributed to theproposition. For example, one might hold that in the sentence

- (2)Colin is a tallyoung man.

the phrase ‘is a tall young man’ contributes to theproposition expressed by (2) the property of being a tall young man,which is its semantic value. Thus, though the semantic value of theword ‘tall’ partly determines the semantic value of thephrase ‘is a tall young man’, the proposition expressed by(2) contains no constituent that is the semantic value of the word‘tall’ alone. Second, one might hold that a sentence mayexpress a proposition (in a context), where the proposition hasconstituents not contributed by any syntactic constituent of thesentence, let alone any word in the sentence. For example, MarkCrimmins [1992] claims that an utterance of the sentence

- (3)It’sraining

expresses a proposition to the effect that it is raining at aparticular time and place. The present tense manages to somehowcontribute the time of utterance to the proposition. But no syntacticconstituent of the sentence contributes the place to the proposition,though Crimmins claims it is a constituent of the proposition expressed.[4] Third, one might hold that certain words simply have no semanticvalues, and so make no contribution to propositions. So-calledneoplanastic ‘ne’ in French might be thought to be anexample of this.

But even if, for one of the above reasons or some other reason, asentence does not express a proposition whose constituents areprecisely the semantic values of words in the sentence, we can stillsay that structured proposition theorists hold that sentencesexpresses propositions, where many (and likely most) constituents ofthe proposition are semantic values of words or phrases occurring inthe sentence. So in the case of (1) and (1a), the constituents of theproposition are precisely the semantic values of the words in (1). Inthe case of (2) and (2a) (given the assumptions made above), theconstituents of (2a) are precisely the semantic values of the name‘Colin’ and the verb phrase ‘is a tall youngman’. And in the case of (3), the proposition it expresses hasthree constituents, two of which are contributed by‘raining’ and the present tense construction.

Thus, ignoring, or at least not dwelling on, the qualifications justmade, we can say that structured proposition theorists hold thatsentences express propositions that are complex entities (most of)whose constituents are the semantic values of expressions occurring inthe sentence, where these constituents are bound together by somestructure inducing bond that renders the structure of the propositionsimilar to the structure of the sentence expressing it.

This highlights an important feature of structured propositionaccounts that distinguishes them from the other main competing accountof propositions, namely the account of propositions as sets ofpossible worlds (to be discussed below). Because structuredpropositions have as parts the semantic values of expressions in thesentences expressing them, the semantic values of those expressionsare recoverable from the semantic values of the sentences (i.e. thepropositions).

It is perhaps worth noting that one could have a theory according towhich the semantic values of expressions in a sentence are recoverablefrom the proposition expressed by the sentence, even though thesemantic values of the expressions are not (mereological or settheoretic) parts of the proposition. For example, George Bealer [1993]formulates what he calls an algebraic conception of propositions (seealso Bealer [1982]). Bealer associates with each proposition a“decomposition tree.” This decomposition tree shows how agiven proposition is the result of the application of logicaloperations to individuals, properties, relations or other propositions(e.g. the application of the logical operation of negation to apropositionP yields a proposition that is true iffP isfalse; the application of the logical operation of singularpredication to an item and a property yields a proposition that istrue iff the item possesses the property, etc.). In general, asentence will express a proposition such that the semantic values ofexpressions in the sentence will occur on the decomposition treeassociated with the proposition. Thus, the semantic values ofexpressions in a sentence will be recoverable from the proposition(together with its decomposition tree) expressed by the sentence.However, Bealer denies that these semantic values are in any senseset-theoretic members or mereological parts of the proposition. Bealerappears to hold that the proposition is metaphysically simple and hasno parts at all. As the term is used here then, Bealer’s is notan account of structured propositions for this reason. We will seebelow that others hold similar “algebraic” conceptions ofpropositions, where the propositions are complex entities consistingof constituents bound together in certain ways and so are structuredpropositions.

Since the structured proposition expressed by a sentence has astructure similar to that of the sentence and has as constituentssemantic values of expressions occurring in the sentence, the theoryof structured propositions allows for distinct necessarily equivalentpropositions. For example, the propositions expressed by‘Bachelors are unmarried’ and ‘Brothers are malesiblings’ presumably are both necessarily true and hence arenecessarily equivalent. But clearly the propositions expressed bythese sentences have different constituents and so are distinct. Theproposition expressed by the former presumably contains the semanticvalue of ‘bachelor’ (perhaps, the property of being abachelor), whereas the proposition expressed by the latterdoesn’t. And the proposition expressed by the latter containsthe semantic value of ‘brother’, whereas the propositionexpressed by the former doesn’t. This is an important virtue ofthe structured proposition view. The fact that it has this feature andthat its main competitor, the possible worlds account of propositions(discussed below), doesn’t is one of the reasons many favor thestructured proposition view.

In discussing recent accounts of structured propositions below, itwill be shown how, on those accounts, sentences that are necessarilyequivalent may express distinct propositions; and how the semanticvalues of expressions in a sentence are recoverable from theproposition expressed by the sentence.

2. From Possible Worlds to Structured Propositions

Because the structured proposition view arose in large part due todissatisfaction with the then prevailing view of propositions,discussing this other account of propositions will help to illuminatestructured proposition views. The late 1950s and 1960s saw thedevelopment of a new sort of model theory, “possible worldssemantics”, for systems of modal logic. In the framework ofpossible world semantics, linguistic expressions are assignedextensions “at” possible worlds. Thus, e.g. names, n-placepredicates and sentences are assigned individuals, sets ofn-tuples of individuals, and truth values, respectively, atdifferent possible worlds. Intuitively, possible worlds are to bethought of as “ways things could have been”, and theassignment of (possibly different) extensions to expressions atdifferent possible worlds is part of capturing this intuition. Thusthere might have been more or fewer cows, and this is reflected in thefact that the extension of ‘cow’ (intuitively, the set ofthings that are cows) can vary from possible world to possibleworld.

Because we wish the extensions of expressions to vary from possibleworld to possible world (at least in some cases), it is natural toassociate with each expression a function from possible worlds toextensions appropriate to that sort of expression. Thus we associatewith names, functions from possible worlds to individuals; withn-place predicates functions from possible worlds to sets ofn-tuples; and with sentences, functions from possible worlds totruth values. Such functions from possible worlds to extensions of theappropriate sort are often called intensions of the expressions inquestion, and the term ‘intension’ shall be used this waythroughout the present work.[5] Now since most think that the extensions of sentences are truthvalues, as indicated above, the intension of a sentence is a functionfrom possible worlds to truth values. Intuitively, it maps a world totrue if the sentence is true at that world. Thus the intension of asentence can be seen as the primary bearer of truth and falsity at aworld: the sentence has the truth value it has at the world in virtueof its intension mapping that world to that truth value. Further,modal operators were typically construed as operating on theintensions of the sentences they embed, and so those intensions couldplausibly be thought of as possessing modal properties. Sincepropositions were traditionally held to be the primary bearers oftruth and falsity and the bearers of modal properties, it was naturalfor possible world semanticists to identify propositions withfunctions from possible worlds to truth values (sententialintensions), or equivalently, sets of possible worlds (the set ofpossible worlds at which the sentence in question is true). Indeed,this identification was thought by many to vindicate the previouslymysterious notion of a proposition.[6] Possible worlds were apparently needed for the model theory of modallogic anyway; why not build propositions out of them?

Current structured proposition accounts arose largely out ofdissatisfaction with the idea that propositions are sets of possibleworlds (or functions from worlds to truth values). In fact, there wereat least two quite distinct motivations for abandoning the view ofpropositions as sets of worlds and adopting the structured propositionaccount.

The first had to do with the way propositions are individuated on apossible worlds account. The view that propositions are sets ofpossible worlds does not individuate propositions very finely. Forexample, consider any pair of sentences that express metaphysicallynecessary propositions, say ‘Bachelors are unmarried’ and‘Brothers are male siblings’. Since these propositions aretrue in all possible worlds, each must be the set of all possibleworlds. But there is only one such set. Thus there is only one suchproposition! Hence these two sentences express the same proposition.(The view also predicts that all true sentences of mathematics expressthe same (necessary) proposition, that any two necessarily equivalentsentences express the same proposition, that the conjunction of anysentenceS with a necessarily true sentence expresses the sameproposition asS, and so on.)

This should make clear that the account of propositions as sets ofworlds is not a structured proposition account. For, as we saw, on astructured proposition account, the semantic values of expressions ina sentence are recoverable from the proposition expressed by thesentence, since those semantic values are constituents of theproposition. This is why on such an account, ‘Bachelors areunmarried males’ and ‘Brothers are male siblings’express distinct propositions: the propositions have differentconstituents. But on the possible worlds account, the property ofbeing a bachelor is in no sense recoverable from or a constituent ofthe proposition expressed by ‘Bachelors are unmarried’.For the latter proposition is just the set of all possible worlds. Howcould the property of being a bachelor be “recovered” fromthis set? Similarly, the property of being a brother is notrecoverable from the proposition expressed by ‘Brothers are malesiblings.’ Again, the latter proposition is just the set of allpossible worlds.

Further, if propositions are sets of possible worlds, belief isconstrued as a relation between individuals and propositions andsentences of the form ‘A believes thatP’assert that the individualA stands in the belief relation tothe proposition expressed by ‘P’, then for anynecessarily equivalent sentences ‘P’ and‘Q’, ‘A believes thatP’and ‘A believes thatQ’ cannot differ intruth value. This means that, for example, if ‘A believesthat 1+1=2’ is true, so is ‘A believes that thereis no greatest natural number’. These consequences of the viewthat propositions are sets of possible worlds were appreciated earlyon; and theorists made a variety of attempts to make theseconsequences seem less unpalatable. Despite these valiant efforts,many philosophers viewed these consequences as a sign that there wassomething very wrong with the view that propositions are sets ofpossible worlds. Thus, philosophers were open to an account ofpropositions that individuated propositions more finely than thepossible worlds account. As we have seen, the structured propositionaccount is just such an account.

In order to make clear the second motivation for abandoning the viewof propositions as sets of worlds and adopting the structuredproposition account, we must discuss the notions of rigid designationand direct reference. A rigid designator is an expression thatdesignates the same individual in all possible circumstances orworlds. In the early 1970’s, Saul Kripke argued inNaming andNecessity that ordinary proper names are rigid designators. Kripkeclaimed that when we consider a sentence containing an ordinary propername, such as

Aristotle was a great philosopher

and ask whether it would have been true or false in variouscounterfactual circumstances, it is the properties of the very sameman, Aristotle, in those circumstances that are relevant to the truthof the sentence. So, ‘Aristotle’ designates the same manin these various counterfactual circumstances; it is a rigiddesignator.

At around the same time, David Kaplan argued that indexicals (e.g.‘I’, ‘here’, ‘now’) anddemonstratives (e.g. ‘that’, ‘you’,‘he’) are directly referential. Concerning directlyreferential expressions, Kaplan wrote:

For me, the intuitive idea is not that of an expression which turnsout to designate the same object in all possible circumstances, but anexpression whose semantical rules provide directly that the referentin all possible circumstances is fixed to be the actual referent. Intypical cases the semantical rules will do this only implicitly, byproviding a way of determining the actual referent, and no way ofdetermining any other propositional component. (Kaplan [1977] p. 493)

Thus, a directly referential expression is a rigid designator: itsassociated semantic rules determine the actual referent of theexpression (in a context) and when evaluating what is said by thesentence containing the expression (in that context) in other possiblecircumstances, this same referent is always relevant. To illustrate,if John utters

I ski.

at the present time and we want to evaluate whether what John said bymeans of that utterance is true or false in other possiblecircumstances, it is John’s properties in those othercircumstances that are relevant. Thus, ‘I’ is rigid: whenevaluating the truth or falsity of what is said by an utterance of asentence containing ‘I’ in counterfactual circumstances,it is the properties of the person whom ‘I’ referred to inthe utterance (the actual utterer) that are relevant.

Kaplan intended to contrast directly referential expressions withexpressions such as definite descriptions, which, though designatingparticular individuals, do so by means of descriptive conditions beingexpressed by the description and satisfied by the designatedindividual. Thus Kaplan wrote that directly referential expressions“refer directly without the mediation of Fregean Sinn asmeaning”. (Kaplan [1977] p. 483) The designation of definitedescriptions is mediated by something like a Fregean sense (i.e. theirassociated descriptive conditions).

Of course, even if descriptions are not directly referential, some arerigid designators. For example, ‘the successor of 1’designates the same individual (2) in all possible worlds. So, thoughall directly referential expressions are rigid designators, some rigiddesignators are not directly referential. As was mentioned above, in apossible worlds semantics linguistic expressions are associated withintensions, functions from possible worlds to appropriate extensions.In the case of expressions designating individuals, these intensionswill be functions from possible worlds to individuals. Note that allrigid designators (whether directly referential or not) will haveintensions that are constant functions: they will be functions thatmap all possible worlds to the same individual. Thus possible worldssemantics tends to blur the distinction between directly referentialexpressions and rigid non-directly referential expressions (e.g. rigiddefinite descriptions). To make the distinction between directlyreferential expressions and rigid non-directly referential expressionsmore vivid, Kaplan invoked the notion of structured propositions:

If I may wax metaphysical in order to fix an image, let us think ofthe vehicles of evaluation—the what-is-said in a givencontext—as propositions. Don’t think of propositions assets of possible worlds, but rather as structured entities lookingsomething like the sentences which express them. For each occurrenceof a singular term in a sentence there will be a correspondingconstituent in the proposition expressed. The constituent of theproposition determines, for each circumstance of evaluation, theobject relevant to evaluating the proposition in that circumstance. Ingeneral the constituent of the proposition will be some sort ofcomplex, constructed from various attributes by logical composition.But in the case of a singular term which is directly referential, theconstituent of the proposition is just the object itself. Thus it isthat it does not just turn out that the constituent determines thesame object in every circumstance, the constituent (corresponding to arigid designator) just is the object. There is no determining to do atall. On this picture—and this is really a picture and not atheory—the definite description

- (1)Then[(snowis slight &n2=9) ∨ (~snow is slight &22=n+1)]

would yield a constituent which is complex although it would determinethe same object in all circumstances. Thus, (1), though a rigiddesignator, is not directly referential from this (metaphysical) pointof view. (Kaplan [1977] p. 494–495)

(Kaplan goes on to attribute this “metaphysical picture”of structured propositions to Russell.) Adopting this structuredproposition account makes it simple to distinguish between directlyreferential expressions and other expressions, rigid or not. Directlyreferential expressions contribute their referents (in a context) tothe propositions expressed (in that context) by the sentencescontaining them. Non-directly referential expressions contribute somecomplex that may or may not determine the same individual in allpossible circumstances. Thus the desire to distinguish clearly betweendirectly referential expressions and other rigid designators promptedKaplan to re-introduce the Russellian notion of a structuredproposition into the philosophical literature (see the discussion ofRussell below). However, Kaplan [1977] tends to treat the notion of astructured proposition as a heuristic device. He repeatedly calls it apicture, explicitly says that it is not part of his theory, and in hisformal semantics he adopts the possible worlds account of propositions(contents of formulae), taking them to be functions from worlds (andtimes) to truth values.

Many current direct reference theorists take the structuredproposition account much more seriously. It is part of their theory inthe sense that when they say that an expression is directlyreferential they are literally saying that it contributes its referentto propositions expressed by sentences containing it, (e.g. see thediscussion of Salmon and Soames below).

3. Some Recent Accounts of Structured Propositions

Having discussed structured proposition accounts in a general way, thebest way to further illuminate these accounts of propositions is todiscuss some recent work on structured propositions. In so doing, weshall see various respects in which accounts of structuredpropositions can differ. Three caveats before proceeding. First, aswas mentioned above, structured proposition accounts, unlike possibleworld accounts of propositions, allow for distinct necessarilyequivalent propositions, and thus individuate propositions more finelythan possible worlds accounts. There are other accounts ofpropositions, or things that are intended to do the work ofpropositions, as in the previously mentioned example of Bealer [1993],that are not structured proposition accounts (given the way that termis used here), but that allow for distinct necessarily equivalentpropositions or things that are to do the work of propositions.Another example is the interpreted logical form account defended byLarson and Ludlow [1993]. Though such accounts will not be discussedhere, the reader should be aware of them and that they are motivatedby many of the considerations that motivate structured propositiontheorists. In particular, they attempt to individuate propositions (orthings that do the work of propositions) more finely than possibleworlds accounts of propositions. Second, discussing a sampling ofrecent work on the view that propositions are structured will not (andis not intended to) exhaust the versions of structured propositionapproaches that there are. Rather, only some of the main issues andcurrent approaches will be highlighted. To that end, three broadapproaches to structured propositions will be discussed; these are theNeo-Russellian Approach, the Structured Intensions Approach, and theAlgebraic Approach. In discussing each approach, a number of authorswho adopt the approach will be mentioned, but for definiteness, only arepresentative of each approach will be highlighted in explaining it.The reader should be aware that these groupings are somewhat loose,and that there may be important differences among authors who aregrouped together. Third, though questions will be raised here andthere, criticisms of the various approaches discussed will be leftaside. The task at hand is simply that of introducing the reader toapproaches to structured propositions; criticizing the variousapproaches is a task for another day.

3.1 The Neo-Russellian Approach

In a series of papers and a book, Scott Soames [1985, 1987, 1989] andNathan Salmon [1986a, 1986b, 1989a, 1989b] have laid out what isprobably the best known current theory of structured propositions.There are some differences of detail between Salmon and Soames, butboth shall be treated here as holding the same view. Though some oftheir contributions will be discussed separately, the main accountfollowed will be that laid out in Soames [1987].

First, Soames [1985,1987] produced what many take to be a devastatingattack on the view of propositions as sets of possible worlds. Soamesshowed that even when one tries to get more fine-grainedpropositions-as-sets-of-worlds by allowing metaphysically impossibleworlds (e.g. worlds in which George Bush is identical with RonaldReagan), inconsistent worlds (in which a thing can both possess andlack a property), and incomplete worlds (where some purported“matters of fact” are simply not settled), the resultingview, when combined with other independently plausible assumptions, isriddled with overwhelming difficulties. These difficulties all stemfrom the fact, noted earlier, that on the worlds view, sentences withvery different syntactic structures and containing words withdifferent semantic values may express the same proposition. Soames[1987] concludes that we ought to give up the view that propositionsare sets of worlds of any sort, and embrace an account of propositionsaccording to which propositions are structured entities, withindividuals, properties and relations as constituents. Soames calledthese structured Russellian propositions. If the syntactic structuresof sentences and the semantic values of words occurring in them arereflected in the structures and constituents of propositions theyexpress, sentences with different syntactic structures and containingwords with different semantic values, whether true in all the sameworlds or not, may express different propositions. It is perhaps worthnoting that having sentences with different syntactic structures andcontaining words with different semantic values express differentpropositions doesn’t require one to hold that propositionsthemselves are structured and contain the semantic values of the wordsas constituents. Still, it is a natural way of accounting for whysentences with different syntactic structures and containing wordswith different semantic values that are true in all the same worldsexpress different propositions. Soames [1987] sketches a formal theoryof structured propositions, including an assignment of structuredpropositions to the sentences of a simple formal language, and adefinition of truth relative to a circumstance for structuredpropositions.

Soames and Salmon are direct reference theorists, holding that names(as well as indexicals and demonstratives) have their referents astheir semantic values and so contribute them to the propositionsexpressed by sentences containing them. Further they hold thatpredicates and intransitive verbs have properties as their semanticvalues; and that transitive verbs have relations as their semanticvalues. Thus they hold that sentences such as

- (4)Scottruns.

- (5)Scott sawNathan.

express the propositions

- (4a)< < o >,R >

- (5a)< < o,o′ >,S >

whereo is Scott ,o′ is Nathan,R is theproperty of running, andS is the relation of seeing. Thenegation of (4) expresses the proposition

- (4b)< NEG,< < o >,R > >

where NEG is the truth function for negation. And the conjunction of(4) and (5) (in that order) expresses the proposition

- (5b)< CONJ< < < o >,R >,< < o,o′ >,S > > >

where CONJ is the truth function for conjunction. Similar remarksapply to sentences formed with other truth functional connectives.Further a sentence such as

- (6)Somethingruns.

expresses the proposition

- (6a)< SOME,g >

where SOME is the property of being a nonempty set andg is thefunction from individualso′ to the proposition< < o′ >,R >, (where, as before,R is the property ofrunning).

It should be easy to imagine the definition of truth relative to acircumstance for structured propositions of the sort mentioned above.For example, (5a) will be true at a circumstancec iff< o,o′ > is in the extensionof the relationS atc. (5b) will be true atciff CONJ maps the truth values of< < o >,R > and< < o,o′ >,S > atc to truth. And (6a) will be true atc iff there is an individual inc thatg maps toa proposition that is true inc, (in that case the set ofindividuals inc thatg maps to propositions true inc possesses SOME).

It should be clear that on this account of propositions sentences thatare necessarily equivalent may express distinct propositions, and thatthe semantic values of expressions in a sentence are recoverable fromthe proposition it expresses. For example, ‘All bachelors areunmarried’ and ‘All brother are male’ are both truein all possible worlds. But on the present view, the former expressesa proposition that has as a constituent a propositional functionmapping an object to the proposition that that object is unmarried;the latter does not. Further, e.g. the semantic value of‘runs’ as it occurs in sentence (4) is recoverable fromthe proposition (4) expresses in that it is a constituent of thatproposition. Similar remarks apply to 5/5a and 6/6a (except that in 6athe semantic value of ‘runs’ is encoded ing: thatis,g maps individualso to the proposition thato runs, which in turn has the semantic value of‘runs’ as a constituent).

Note that this account of propositions (including the commitment tonames being directly referential) entails that sentences that differonly with respect to coreferential names express the same proposition.Thus

Mark Twain is Samuel Clemens.

and

Samuel Clemens is Samuel Clemens.

express the same proposition on this view. Many have found this resultincredible, since it would appear that the one sentence could beinformative and the other not. Salmon and Soames also hold that‘believes’ expresses a relation between individuals andpropositions, so that ‘Scott believes that Mark Twain is SamuelClemens’ expresses a proposition to the effect Scott stands inthe believes relation to the proposition expressed by ‘MarkTwain is Samuel Clemens’. But then it follows that ‘Scottbelieves that Mark Twain is Samuel Clemens’ and ‘Scottbelieves that Samuel Clemens is Samuel Clemens’ express the sameproposition (since the embedded sentences in both belief ascriptionsexpress the same proposition) and so cannot diverge in truth value.Many have found this consequence of the Salmon-Soames view ofpropositions (and belief ascriptions) hard to swallow as well.

Salmon [1986] is largely an extended defense of these two consequencesof the Salmon-Soames view. It is beyond the scope of the present workto explain Salmon’s defense and the interested reader shouldconsult that work directly.[7] Soames [2002] deals with these issues, among others, as well.

In the formal semantics offered by Salmon and Soames, propositions areorderedn-tuples (or concatenations ofn-tuples), as are(4a), (5a), (5b) etc. above. But since Salmon and Soames say nothingexplicitly about the matter, it is unclear whether thesen-tuples and concatenations merely represent propositions inthe formalism, or whether Soames and Salmon take them to bepropositions. If the former, then the Salmon and Soames view isincomplete and we need to be told what propositions really are, andmore specifically what it is that really holds propositions together(i.e. what the corner brackets in (4a), (5a) etc. stand for). If thelatter, then the view at least seems to have trouble accounting forsome of the properties possessed by propositions. Propositions havetruth conditions: they are true or false, depending on how the worldis. So if some orderedn-tuples are propositions, some orderedn-tuples have truth conditions. But orderedn-tuplesdon’t seem to be the kinds of things that have truth conditions.Indeed, presumably many orderedn-tuples have no truthconditions, (e.g. < 1,2,3 >). So how/why did thosen-tuples that are propositions come to have truth conditions?Similar remarks apply to modal properties. Propositions are necessary,contingent, and possible. These, again, don’t seem to beproperties ofn-tuples. Finally, if propositions are orderedn-tuples, that is, set theoretic constructions, it is hard tosee why a particular set theoretic construction is the proposition inquestion (and so has truth conditions, modal properties, etc.) asopposed to some other set theoretic construction that seems equallywell suited to the task. For example, we said that the sentence

- (4)Scottruns.

expresses the proposition/set theoretic construction

- (4a)< < o >,R >

But the following set theoretic construction seems equally suited tobe the proposition (4) expresses:

- (4b)< R,< o > >

So why it is that (4a), instead of (4b), is the proposition (4)expresses, and has modal properties and truth conditions?

These questions as to what holds structured propositions together andgives them their structure, and how/why proposition have truthconditions turns us to other recent work within the neo-Russellianapproach. While adopting more or less the same view as Salmon andSoames on the semantic values of different kind of words (thoughclaiming to be strictly neutral on the question of what the semanticvalues of names and predicates are), Jeffrey C. King [1995, 1996,2007, 2009] develops a view as to what binds the constituents ofpropositions together and how/why propositions have truth conditions.He holds that propositions are notn-tuples and that a complexrelation binds together the constituents of a proposition and providesthe proposition with its structure.[8] Further, King is motivated by the idea that propositions cannot bethe kinds of things that by their very natures and independently ofminds and languages have truth conditions. Hence, a radical feature ofKing’s view is that we speakers of natural languages endowpropositions with their truth conditions, as a result of which hecalls his account a naturalized account of propositions.

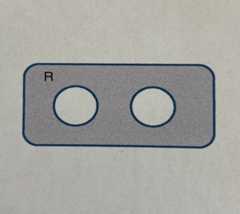

In order to explain what complex relation King claims binds theconstituents together, consider the sentence ‘Dara swims’and, idealizing considerably for the sake of exposition, assume thatits syntactic structure at LF is as follows:

Figure 1.

Call the syntactic relation between ‘Dara’ and‘swims’ here R. King sometimes callsR thesentential relation of the sentence ‘Dara swims’. Amongthe reasons that the English sentence in Figure 1 is true iff Daraswims is that the sentential relationR is interpreted byEnglish speakers in a certain way. We interpret it asascribing the semantic value of ‘swims’ to thesemantic value of ‘Dara’. As King points out, this is acontingent matter. There might have been a language containing thesentence ‘Dara swims’ the speakers of which took thesentence to be true iff Dara fails to possess the property of swimming.[9] The difference in truth conditions of the sentence ‘Daraswims’ in these two languages is due to the speakers of thelanguages interpreting the syntactic concatenation in the sentencedifferently. And of course we English speakers interpretingRin the way we do (described above) is not an isolated matter. Ingeneral we interpret syntactic concatenation by composing semanticvalues of the concatenated lexical items in certain ways.[10] King sometimes puts this by saying that we interpret syntacticconcatenation as instructing us to compose semantic values in certainways. The fact thatR in Figure 1 is interpreted by Englishspeakers as ascribing the semantic value of ‘swims’ to thesemantic value of ‘Dara’ is expressed by saying that inEnglish,R encodes ascription.[11] It is the fact thatR encodes ascription in English that makesthe English sentence ‘Dara swims’ have truth conditionsrather than being a list of Dara and the property of swimming.[12]

Returning to the main theme, we are trying to say what relation holdstogether Dara and the property of swimming in the proposition thatDara swims on King’s view. King claims that we ought to be surethat we pick a relation such that there are good independent groundsfor thinking that Dara and the property really do stand in thatrelation, so that the proposition in question exists. Given that‘Dara’ has Dara as its semantic value and that‘swims’ has the property of swimming as its semanticvalue, then in virtue of the existence of the English sentence‘Dara swims’, here is a two-place relation that Dara andthe property of swimming stand in:

(Relation)

there is a language L, a context c and lexical items a and b of Lsuch that a and b occur at the left and right terminal nodes(respectively) of the sentential relation R that in L encodesascription and ___ is the semantic value of a in c and ___ is thesemantic value of b in c.

Following King, let’s call an object possessing a property, orn objects standing in ann-place relation, or an objectstanding in a relation to a property, orn properties standingin ann-place relation and so on a fact. Then since Dara standsin the above relation to the property of swimming, the following is afact:

(Fact)

there is a language L, a context c and lexical items a and b of Lsuch that a and b occur at the left and right terminal nodes(respectively) of the sentential relation R that in L encodesascription and Dara is the semantic value of a in c and the propertyof swimming is the semantic value of b in c.

That the English sentence ‘Dara swims’ exists, that‘Dara’ has as its semantic value (in any context) Dara andthat ‘swims’ has as its semantic value (in any context)the property of swimming jointly suffice for the existence of thisfact. Equally, that the German sentence ‘Dara schwimmt’exists (and that the words in the sentence have the semantic values incontext that they do) and that the English sentence ‘Iswim’ taken in a context in which Dara is the speaker existseach suffices for the existence of this fact as well. Without theexistence of any such sentences, the fact in question wouldn’texist.

(Fact), or what is the same thing, Dara standing in (Relation) to theproperty of swimming, is almost what King claims is the propositionthat Dara swims. To see what more needs to be added, note that thereis no reason to think that (Fact) has truth conditions and so iseither true or false. But consider again (Relation), which relatesDara and the property of swimming in (Fact). Since Dara stands in(Relation) to the property of swimming in the proposition that Daraswims, call (Relation) the propositional relation of the propositionthat Dara swims. Now if this propositional relation encodedascription, as does the sentential relation R that is a component ofthe propositional relation, the proposition would have truthconditions. For in that case, the propositional relation would beinterpreted as ascribing the property of swimming to Dara and so theproposition would be true iff Dara possesses the property of swimming.[13] Hence, King claims that the following fact is the proposition thatDara swims, where we now include as part of the fact/proposition thatthe propositional relation in it encodes ascription:there is alanguage L, a context c and lexical items a and b of L such that a andb occur at the left and right terminal nodes (respectively) of thesentential relation R that in L encodes ascription and Dara is thesemantic value of a in c and the property of swimming is the semanticvalue of b inc.[14] Since Dara does possess the property of swimming, there is also thefact of her possessing this property. But note that this fact is quitedistinct from the fact that King claims is the proposition that Daraswims. Still, the former makes the latter true. But had there been nofact of Dara possessing the property of swimming, the fact that is theproposition that Dara swims would still have existed and sadly wouldhave been false.[15]

King claims that his account has several significant virtues.[16] First, on his account it is hard to deny that propositions existgiven fairly minimal assumptions; and there is no mystery about whatthey are. Second, his theory is naturalized, in the sense that it issomethingwe do that endows propositions with truthconditions. Third, and related to the previous point, we can give someexplanation as to how and why propositions have truth conditions.[17] On the proposed explanation the representational powers of sentencesand their users are explanatorily prior to those of propositions.

In more recent work, King has emended his account of propositions invarious ways. On King’s [2007] view, because of the role thesyntax of a sentence plays in the propositional relation expressed bythe proposition it expresses, sentences with any difference in theirsyntactic structures express different proposition. However, in bothKing, Speaks, & Soames [2014] and especially in King [2018], Kingformulates a version of his view that allows sentences with quitedifferent syntactic structures, whether in the same or differentlanguages, to express the same proposition. In King, Speaks, &Soames [2014], King gives his most explicit account to date of how itis that propositions have truth conditions and so represent the worldas being a certain way.[18]

Next, we turn to a discussion of a view of propositions recentlychampioned by Scott Soames [2010a, 2010b]. Soames follows King [2007,2009] in rejecting the view that propositions are things that arerepresentational, and so have truth conditions, independently of mindsand languages on the grounds that such a view is ultimately mysteriousand unintelligible. Again following King, Soames thinks that the factthat propositions are representational must ultimately be explained interms of the representational capacities of agents. However,Soames’ positive account of how/why propositions have truthconditions differs in important ways from King’s.

Soames begins with the notion of the mental act of predication, whichhe takes to be primitive. However, by way of illustration, if an agentperceives an objecto as red, and so has a perceptualexperience that representso as being red, the agentpredicates redness ofo. Similarly, if an agent“thinks of”o as red[19], or “form[s] the nonlinguistic perceptualbelief thato is red”.[20] For Soames, predicating redness ofo does not amount tobelieving that o is red. To believe thato is red, onemust predicate redness ofo and do something like endorse thepredication. It is hard to say precisely whatpredicatingamounts to since the notion is primitive for Soames. An agentpredicating redness ofo is an event token. Of course there maywell be many event tokens of agents predicating redness of some objecto by an agent perceiving it as red, an agent thinking of it asred and so on. Soames claims that the proposition thato is redis the eventtype of an agent predicating redness ofo. Other more complex propositions are identified with eventstypes of agents performingsequences of primitive mental acts.[21] Soames doesn’t say what he takes events (types or tokens) tobe. But since he thinks that propositions are structured entities withconstituents, he must think that event types are structured entitieswith constituents. Presumably, the proposition thato isred—the event type of an agent predicating redness ofo—haso and redness as constituents.

Like King, Soames grounds the representational capacities ofpropositions in the representational capacities of agents. Soamesclaims that the event tokens of agents ascribing redness tooare things that inherently have truth conditions. They are things thatare inherently true iffo is red. These tokens are for Soamestokens of the event type that is the proposition thato is red:the event type of an agent predicating redness ofo. Soamesclaims that the event type thato is red has truth conditionsbecause of its “intrinsic connection” to the event tokensof agents predicating redness ofo, which, as indicated, arethemselves things that inherently have truth conditions.

In King, Speaks, & Soames [2014] and Soames [forthcoming], Soamesamends his theory of proposition in several respects. Two of thosechanges are the following. First, Soames [2010] had rejected the viewthat cognitive act types are propositions on the grounds that act typeare things that we do, but propositions are not. In King, Speaks,& Soames [2014], Soames makes clear that he no longer finds thisargument persuasive and is inclined to identify propositions withcognitive act types. Second, Soames gives a new account representthings as being a certain way. On the new account, propositionsrepresent things as being a certain way in a derivative sense. Just asan act can be intelligent in the derivative sense that in performingit an agent is acting intelligently, the proposition that o is redrepresents in the derivative sense that in performing that act anagent represents o as being red.

Peter Hanks [2015] defends a view with some similarities toSoames’ view discussed above. As did Soames, Hanks follows Kingin endorsing the three novel claims from King [2007] and subsequentwork mentioned above: (i) Hanks rejects theories according to whichpropositions have truth conditions and so represent the world as beinga certain way by their very natures and independently of minds andlanguages as mysterious; (ii) holds that an adequate theory ofpropositions mustexplain how\why propositions have truthconditions and so represent the world as being a certain way; (iii)and holds that since the representational capacities of propositionscannot be something they have inherently and by their natures, theirrepresentational capacities must derive from and be explained by therepresentational capacities of thinking agents.

In simple cases of judging and asserting, Hanks claims we performactions of predicating properties of objects. In judging that DonaldTrump is a demagogue without speaking, one thinks of Trump (refers tohim in thought), thinks of the property of being a demagogue(expresses the property in thought) and predicates the property ofTrump. In asserting that Trump is a demagogue, one refers to him,expresses the property and predicates it of him, here using linguisticmeans. According to Hanks, in predicating a property of an object, oneportrays the object as being a certain way and so does something thatis true or false. Hence, Hanks claims these token acts of predicatingare true or false. Hanks notion of predication is inherently assertiveand committing, unlike Soames’ notion of predication. There isnot some non-committal thing you do in predicating and then addendorsement or commitment. On Hanks view, predicatingiscommitting to the object possessing the property in question. Theproposition that Donald Trump is a demagogue is the acttype ofpredicatingbeing a demagogue of Trump. Hanks holds that thisact type would exist even if it had no tokens. In general, whetherthey have tokens or not, Hanks holds that the act types that arepropositions exist.

The proposition that Trump is a demagogue is the act type of referringto Trump, expressing the property of being a demagogue and predicatingit of Trump, as we have seen. What Hanks calls theinterrogativeproposition expressible by the question ‘Is Trump ademagogue?’ is the act type of referring to Trump, expressingthe property of being a demagogue and combining Trump and the propertyin an interrogative way (rather thanpredicating the propertyof Trump). Hanks gives a similar account of theimperativeproposition expressed by the command ‘Trump, be ademagogue!’ As a result, Hanks rejects the claim that there issome common underlying content running through the (assertive)proposition, imperative proposition and interrogative propositionregarding Trump being a demagogue. There are just three differentpropositions here with their different “forces”(assertive, interrogative, imperative) built in.

Hanks’ explanation of why propositions as act types of the sortdescribed have truth conditions comes in two steps. First, Hanksargues that token acts of predicating properties of objects have truthconditions. Hanks recognizes that some may doubt whether act tokensare the kinds of things that can be true and false. His main argumentthat they can be is that we have adverbial modifiers‘truly’ and ‘falsely’ and that these attributeproperties to action tokens. So just as ‘quickly’ in‘Obama quickly stated that Clinton is eloquent.’attributes a property to Obamas’s action, so Hanks claims that‘truly’ in ‘Obama truly stated that Clinton iseloquent.’ attributes the property of being true to an action ofObama. Hanks then tries to argue that the actiontype ofpredicating being a demagogue of Cruz inherits the property of havingtruth conditions from its instances. Note that here it must be actualand possible instances that truth conditions are inherited from, sinceHanks wants propositions that have never been and never will betokened to have truth conditions. The argument here is complex sinceHanks notes that types inherit certain kinds of properties from tokensand not others. Hence, Hanks seeks to explain why the having of truthconditions is the kind of property a type inherits from its (actualand possible) tokens.

On Hanks’ theory there are many more propositions than one mighthave thought. First, there is the proposition that is the act typeconsisting of referring to Clinton using ‘Clinton’ andpredicating eloquence of her. It is true iff Clinton is eloquent. Thenthere is a distinct proposition with those same truth conditions thatis the act of referring to Clinton in any way whatsoever andpredicating eloquence of her. Next, there is another proposition withthese same truth conditions consisting of the act of referring toClinton using ‘Clinton’ while thinking of her asObama’s former secretary of state and predicating eloquence ofher. In addition, there is another proposition with the same truthconditions consisting of referring to Clinton using‘Clinton’ while thinking of her as a former first lady andpredicating eloquence of her. And so on. Again, all these propositionsare true iff Clinton is eloquent. There is even a propositionconsisting of referring to Clinton using ‘Clinton’ whiledrawing a round square and predicating eloquence of her.[22]

Above we saw that for Hanks, predication endows propositions with aninherent element of judgment or assertion. Predicating a property ofan objectcommits the predicator to the object having thatproperty. For Hanks, she did something false if it doesn’t. Butthis raises a problem for him. In disjunctive, negated, conditionalpropositions and others, embedded propositions do not have assertiveforce. They aren’t asserted. But if these embedded propositionsinherently have an assertoric or judgmental element, how can this be?To address this Hanks claims that ‘or’, ‘if’and ‘not’ create cancellation contexts. Since e.g.‘or’ creates acancellation context on Hanks’view, in uttering the following sentence I fail to assert that Trumpis a demagogue:

Trump is a demagogue or Clinton is eloquent.

Each disjunct expresses a proposition that includes as a sub act theact of predicating a property of the object according to Hanks. Butthe predication is cancelled. Hence, the asserting/committing elementin the proposition is cancelled. Hanks must walk a very fine linehere. The inherently assertive committal aspect of predication is whatexplains both that propositions are true and false and that unembeddedpropositions make assertions.[23] To explain why some embedded propositions don’t makeassertions, Hanks appeals to the notion of the predication beingcancelled in virtue of occurring in a cancellation context. But ofcourse Hanks will want to say that the embedded proposition still hastruth conditions and is true or false. Somehow in canceling thepredication, though assertive force is cancelled the truth conditionsand truth-value aren’t, even though predication is responsiblefor both.

Above it was mentioned that King [2007] and subsequent work endorsedthree novel claims about propositions. Two of these are: (i) theoriesaccording to which propositions have truth conditions and so representthe world as being a certain way by their very natures andindependently of minds and languages are mysterious and to berejected; (ii) an adequate theory of propositions mustexplainhow\why propositions have truth conditions and so represent the worldas being a certain way.[24] It was also noted that Soames and Hanks follow King in this respect.In a sense, Speaks does too insofar as he feels the need to explainthe “aboutness” or intentionality of some mental states.[25] So most recent literature has taken onboard King’s two claimsabove. Philosophy being what it is, however, there have been recenttheorists who want to return to something like the classical theoriesof Frege and Russell, where propositions were thought to be mind andlanguage independent abstract objects that by their very natures hadtruth conditions and so represent the world as being a certain way. Onsuch a view, both of King’s claims are rejected. Propositionsare precisely held to have truth conditions by their natures andindependently of minds and languages; and it is denied that there canbe any explanation of how/why propositions have truth conditions.Trenton Merricks [2015] defends such a view. According to Merricks,propositions are abstract, necessary existents that essentiallyrepresent the world as being a certain way.[26] He also holds that the fact that propositions essentially representthings as being a certain way is primitive. That is, this fact has no explanation.[27] Further, Merricks holds that propositions are simple: they have no constituents.[28] On this last point at least Merricks departs from the classical viewsof Frege and Russell on which propositions do have constituents.

Lorraine Juliano Keller [2014] expresses sympathy for a similar viewthat she callspropositional primitivism. On this view,propositions are fine-grainedsui generis entities. They arenot reducible to nor can they be explained by entities in anotherontological category. Her primitivist thinks that not much of anythingcan be said about the inner nature of propositions except that theyare abstract, mind and language independent entities with noconstituents or structure. While King, Soames, Hanks and perhapsSpeaks see in such a view mystery or worse, primitivists like Kellerand Merricks see elegance and simplicity.

3.2 The Structured Intension Approach

Having seen the main features of neo-Russellian approaches, let usturn to structured meaning accounts. The roots of these accounts canbe traced to Rudolf Carnap [1947], and his notion of intensionalisomorphism. David Lewis [1972] and Max Cresswell [1985] have workedout similar, detailed versions of the structured meanings approach,though there are important differences in their views.Cresswell’s [1985] version of the view will be discussed here.[29] Because our concern is with conceptions of structured propositions,there are many features of Cresswell [1985] that will not be discussed(e.g. Cresswell’s account of the semantics of verbs ofpropositional attitude).

Both Lewis [1972] and Cresswell [1985] are motivated by some of thesame considerations that motivated neo-Russellians like Salmon andSoames. Lewis and Cresswell both wish to find a more fine grained“semantic value” for sentences than functions from worlds(or, as in Lewis [1972], indices) to truth values or, equivalently,sets of worlds. For example, Cresswell [1985] claims that verbs ofpropositional attitude are (sometimes) sensitive to more than theintensions (functions from worlds/indices to truth values) of thesentences they embed. Thus Cresswell claims that

…one might easily have two sentencesα andβ that are true in exactly the same worlds and yet aresuch that

xφs thatα

is true, but

xφs thatβ

is false. (Cresswell [1985] p. 73;φ of course is a verb ofpropositional attitude).

Thus Cresswell wishes to associate with a sentence (or moreaccurately, a ‘that’ clause) some semantic value that ismore fine grained than a set of worlds, so that attitude verbs may(sometimes) distinguish between sentences that are true in exactly thesame worlds. Strictly, Cresswell holds that sometimes attitude verbsare sensitive only to the sets of worlds in which the sentences theyembed are true (i.e. their intensions); but sometimes attitude verbsare sensitive to more than this. In these latter cases, Cresswellwishes to associate a semantic value more fine grained than a set ofworlds with the embedded sentence (or ‘that’ clause).Cresswell accomplishes this by holding that ‘that’ inEnglish attaches to a sentence to form a name, and that‘that’ in this role is highly ambiguous. In one of itsmeanings, ‘that’ attaches to a sentence and forms a nameof the intension of the sentence (i.e. the set of worlds in which itis true).[30] In such cases, the attitude verb is sensitive only to the intensionnamed by the ‘that’ clause following it. However,‘that’ has another meaning on which it combines with asentence to form the name of a much more fine-grained entity (in thesense that sentences true in all the same worlds may be associatedwith different fine-grained entities). In such cases, verbs ofattitude are sensitive to differences in these fine-grained entities.Since our concern is with structured propositions, or with semanticvalues of sentences more fine grained than sets of worlds, the focuswill henceforth be on Cresswell’s account of these fine-grainedentities named by some ‘that’ clauses.[31] Henceforth, then, when the fine grained entity associated with asentence or ‘that’ clause on Cresswell’s view isdiscussed, what is being discussed is what a ‘that’ clausecontaining the sentence names, given that the meaning of‘that’ in the ‘that’ clause is the one thatwhen combined with the sentence yields a name of the most fine grainedentity named by any ‘that’ clause in which the sentenceoccurs. This is important to bear in mind, since for Cresswell,strictly speaking, a sentence not in a ‘that’ clause doesnot express this fine grained entity.

Consider the sentence

- (7)Maxruns.

For Cresswell, the meaning of a predicate like ‘runs’ isessentially its intension: a function from individuals to sets ofworlds (it maps an individual to the worlds at which she runs).[32] LetIr be this intension. The meaning of aname like ‘Max’ (in some cases at least) is simply itsreferent:o. Thus, the fine grained entity associated with (7)is the ordered pair:

- (7a)< o,Ir >

The negation of (7) will be associated with the following:

- (7b)< NOT,< o,Ir > >

where NOT is the function from sets of worlds to sets of worlds thatmaps a set of worlds to its complement. Finally, the sentence:

- (8)Someoneruns.

is associated with

- (8a)< Σ,Ir >

where Σ is the function from functions from individuals to setsof worlds to sets of worlds such that Σ(f)={w: forsomeo,w is inf(o)}.

It should be clear that as on the neo-Russellian approach, sentencesthat are true in all the same worlds may be associated with differentfine grained entities of the sort posited by Cresswell. For example,even if ‘All brothers are siblings’ and ‘Allbachelors are male’ are true in exactly the same worlds, thefine grained entity associated with the latter will contain themeaning (function from individuals to sets of worlds) of‘male’ and the fine grained entity associated with theformer will not. It should also be clear that the semantic values ofexpressions are recoverable from the propositions expressed bysentences containing them. For example, the semantic value of‘runs’ as it occurs in (7) is a constituent of thefine-grained entity expressed by (7) (i.e. (7a)). Similar remarksapply to (7b) and (8a).

A final remark about Cresswell’s view is in order. Thefine-grained entities we have been discussing are what verbs ofpropositional attitude are sensitive to when they are sensitive tomore than the intension/set of worlds associated with a sentence theyembed. However, they do not seem to be the primary bearers of truthfor Cresswell. For Cresswell, each sentence is associated with a setof worlds/intension, which Cresswell calls a proposition; and thetruth or falsity of a sentence at a world is determined by whatproposition it expresses. So these seem to be the primary bearers oftruth and falsity for Cresswell.[33] Thus, it appears that for Cresswell, in contrast to theneo-Russellians, the primary bearers of truth and falsity and the finegrained entities associated with the sentences (or ‘that’clauses) that verbs of attitude embed and to which they are(sometimes) sensitive are different.

3.3 The Algebraic Approach

Next, we turn to algebraic approaches. Though Bealer in some senseadopts an algebraic approach to propositions (see the abovediscussion), he apparently holds that propositions have no (settheoretic or mereological) parts, and so doesn’t count as astructured proposition theorist in the sense in which the term is usedhere. Thus, we will consider here adherents to the algebraic approachwho do hold that the propositions yielded by their algebras arecomplex and have “parts”. Aside from Bealer [1979, 1982and 1993], work in this tradition includes Edward Zalta [1983 and1988], and Christopher Menzel [1993]. The focus here will be on theformulations in Edward Zalta [1988]. Though Zalta has an extensive,axiomatized theory of propositions, and ordinary and abstractindividuals, properties, and relations, we confine our attention hereto his view about propositions. Still, since Zalta views propositionsas zero-place relations, we will say something about his views onproperties and relations.

Advocates of the algebraic approach such as Zalta, like theneo-Russellians and the advocates of structured meaning approaches,think that a good theory of propositions must allow for distinct,necessarily equivalent propositions. Thus, he writes:

“Necessarily equivalent propositions may be distinct. If thetheory of propositions is not fine-grained enough to distinguishnecessarily equivalent propositions, the ability to accuratelyrepresent belief is lost” (Zalta 1988, p. 57)

To appreciate how Zalta achieves the goal of having a fine-grainedtheory of propositions, we begin by discussing how he views relationsgenerally, since, as just mentioned, Zalta takes propositions to bezero-place relations (and properties to be one-place relations). Zaltaholds that relations are “primitive entities”, by which hemeans that they are not to be explained or “defined” interms of other entities/notions. But at least some relations arecomplex. For example, if we take a two-place relation (betweenobjects)Rxy and “plug” one of itsargument places with the objectb, we get the one-placerelation (property)Rxb (“bearingRtob”).[34] This one-place relation is complex, havingb andR asparts. Similarly, if we take a three-place relationSxyz and “universalize” thethird argument position, we get a two place relation that we mightrepresent thus: (z)Sxyz(“x andy (in that order) stand inS toeverything”). Here again, the two-place relation is complex,having S and (something corresponding to)“universalization” as parts. Zalta’s idea is thatproperties, relations and individuals can be “harnessedtogether” to form new, complex relations. In his axiomatizedtheory of relations, Zalta introduces a comprehension schema forrelations (see Zalta [1988] p. 46) that insures that all manner ofcomplex relations will be available. To insure that all instances ofthe comprehension schema are true in all interpretations of hisaxiomatized theory, Zalta has these interpretations include thefollowing group of “logical functions”:PLUGi, NEG, COND, UNIVi,REFLi,j CONVi,j,VACi, NEC, WAS and WILL. Roughly (and suppressingreference to worlds and times) PLUGi is a functionthat maps ann-place relationR and an objectbto then-1 place relationR′ such that< o1, …,oi-1,oi+1,…,on > stand inR′ iff < o1, …,oi-1,b,oi+1, …,on > stand inR. NEG is afunction that maps ann-place relationR to ann-place relationR′ such thatn thingsstand inR′ iff they don’t stand inR.[35] Thus the repeated application of these functions yields appropriaterelations to make true the instances of Zalta’s comprehensionschema for relations. For example, consider the following twoinstances of his comprehension schema (where ‘F′ isa variable ranging over one-place relations; ‘b’ isa name of an individual; and the other predicate letters are constantsand so name particular relations):[36]

(∃F)(Fx iffRxb)

(∃F)(Fx iff ~Px)

If we apply PLUG2 to the individual denoted by‘b’ and the (two-place) relation denoted by‘R’, we get a one-place relation that makes thefirst instance of the schema true; and if we apply NEG to thedenotation of ‘P’, we get a one-place relation thatmakes the second instance true.

As we have mentioned, propositions are zero-place relations for Zalta.Thus, PLUGi and the rest of the “logicalfunctions” mentioned above can be applied to various entities toyield propositions. Thus the proposition expressed by a sentence like

Ed runs.

is the result of applying the PLUG1 function to theproperty of running and Ed. This proposition consists of Ed saturatingthe one argument place of the running property. Similarly, a sentencelike

Ed does not run.

expresses the proposition that is the result of applyingPLUG1 to running and Ed as before, and then applying NEG tothe output of PLUG1. Finally, a sentence like

Everything runs.

expresses the result of applying UNIV1 to the property ofrunning. This idea that there is some group of “logicalfunctions” whose repeated application to some other entitiesyield complex propositions (and relations) is characteristic of whatare being called algebraic approaches.

It should be clear that necessarily equivalent sentences may expressdistinct propositions on Zalta’s view. For example, thesentences ‘All brother are male siblings’ and ‘Allbachelors are unmarried’ express propositions that are true inall possible worlds. But the first expresses a proposition thatresults from applying COND to the properties of being a brother andbeing a male sibling, and applying REFL1,2 and thenUNIV1 to the output of COND. The second does not, butinstead results from applying these functions in the same order to theproperties of being a bachelor and being unmarried. Further, it shouldbe clear that the semantic values of expressions are recoverable fromthe propositions expressed by sentences in which they occur. E.g. bothEd and the property of running, which are the semantic values of‘Ed’ and ‘runs’, are constituents of theproposition that Ed runs, which is expressed by ‘Ed runs’,since this proposition consists of Ed saturating the one argumentplace in the property of running.

Having sketched Zalta’s view of propositions it is worthmentioning a couple points about it. First, at least in some cases,what binds together the constituents of a proposition is in some sense“built into” one of the constituents of the propositionfor Zalta, (as we shall see below, the same is true for Frege andRussell). Consider again the sentence:

Ed runs.

Recall that this sentence expresses the proposition that results fromapplying PLUG1 to Ed and the property of running. Theoutput is Ed saturating (“plugged into”) the one argumentplace of the property of running. There are two things to notice aboutthis proposal. First, it is one of the constituents of theproposition, the running property, that binds the constituents of theproposition together. The proposition is held together in virtue of Ed“plugging” the one argument place in the running property.Second, the proposition just is Ed “plugging”/possessingthat property!

Such a view immediately raises a worry about false propositions(discussed below in connection with Russell’s POM account ofpropositions). For one might argue as follows. Suppose Eddoesn’t run. Then Ed doesn’t plug/saturate the oneargument place in the property of running (i.e. doesn’t possessthis property). But Ed possessing the running property just is theproposition that Ed runs. Thus there is no proposition that Ed runs.Similar reasoning shows that any other false proposition fails toexist. So there are no false propositions.

Obviously, Zalta does not want to be saddled with this result, and heisn’t. He holds that the even if Ed doesn’t run, there isa proposition consisting of Ed saturating the argument place in therunning property. That proposition simply isn’t true. To put thepoint somewhat paradoxically, even if Ed doesn’t run, hepossesses the property of running, so that we have our (false)proposition.

To some, Zalta will appear to have confused a proposition with whatmakes it true. Ed possessing the running property isn’t theproposition that Ed runs, one might think. It is what makes thatproposition true! Of course Zalta must deny this. Having identifiedthe proposition with the thing that other theorists take to be whatmakes the proposition true, Zalta holds that nothing outside of theproposition makes it true:

The metaphysical truth or falsity of these logical complexes[propositions] is basic. If a proposition is true, there is nothingelse that “makes it true”. Its being true is just the waythings are (arranged). (Zalta [1988] p.56)

So the idea is that whether Ed runs or not, he saturates the oneargument place in the running property, so that we have theproposition that Ed runs. If Ed does run, so that the proposition istrue, it is just a basic, brute fact that the proposition is true.

Finally, though we shall not go into it here, it is worth mentioningthat when Zalta gets to the semantics of verbs of propositionalattitudes, it is not only the propositions considered thus far thatare objects of the attitudes and make belief ascriptions true orfalse. Zalta ends up claiming that sentences embedded with respect toattitude verbs are ambiguous, sometimes expressing the sorts ofpropositions we are discussing, and sometimes expressing otherpropositions that instead of containing the individuals, propertiesand relations thus far discussed, contain senses of these individuals,properties and relations. These senses are “abstract”individuals and relations, instead of the ordinary individuals andrelations discussed thus far. Hence Zalta ends up with a theory ofbelief ascriptions that invokes both fine-grained propositions andneo-Fregean senses. The interested reader should consult Zalta [1988].

3.4 The Pictorial Approach

Andrew Bacon [2023] defends a view of structured propositions thathe callsthe pictorial view. On this view, propositionshave individuals, properties and relations as constituents, includingproperties of properties and so on.[37] Bacon uses what he callsrelationaldiagrams to represent propositions and their constituents. Here is a diagram of a two-place relationR:

The holes here are where the two arguments of the relation go. Hereis a diagram of the proposition thata bearsRtob:

Here the diagram represents the individualsa andboccupying the two argument places inR, yielding theproposition thata bearsR tob. Importantly, on Bacon’s view there are multiple waysof building a proposition. In the case of the above proposition, wecan build it by first plugginga into the left hole, yielding theproperty thata bearsR to ___, which is represented by the following diagram:[38]

We then plug the right hole inR with theindividualb, yielding the proposition thatabearsR tob. Or we could instead build theproposition by first pluggingb into the right holeofR yielding the property ___ bearsRtob:

We then pluga intoR’s left hole, yieldingthe proposition thata bearsR tob.

The constituentsa andb havepositions inthe proposition thata bearsR tob atleast in the sense that we can say thata comesbeforeb in that proposition and thata has the sameposition in the proposition thata bearsRtob thatd has in the proposition thatdbearsS toc. However, Bacon explicitly denies thatthe relationR has a position in the propositionthata bearsR tob. Looking at the diagramof that proposition above, one way to see why Bacon says that itdoesn’t make any sense to talk of whetherR comesbefore or aftera orb in the proposition that abearsR tob. Bacon says that talking about whetherR comes before or aftera orb in theproposition thata bearsR tob would belike talking about whether California is east or west ofSacramento.

Finally, one of the more interesting features of Bacon’stheory of structured propositions is that it straightforwardly avoidsRussell-Myhill style paradoxes, whichprima facie afflict manyother theories of structured propositons.[39] The principles that that theseparadoxes call into question are simply not embraced by the pictorialview Bacon endorses.

4. Historical Antecedents to Current Views: Frege

As with many ideas discussed in contemporary philosophy of language,the idea that propositions are structured is present in GottlobFrege’s writings. Frege had a view both about the constituentsof structured propositions and about what held these constituentstogether in the proposition. Frege held that simple linguisticexpressions are associated with entities he called senses. Thoughthere is some controversy about precisely how to understand the notionof sense, Frege explicitly distinguishes the sense of a linguisticexpression from both the subjective ideas speakers associate with theexpression and the thing in the world the expression “standsfor”. Further, the sense of an expression determines what thingin the world the expression stands for. Thus the sense of a propername such as ‘Ronald Reagan’ must be distinguished fromany subjective ideas speakers associate with the name (e.g. feelingsof anger, fondness, etc.) and from Reagan himself. And the sense ofthe name “picks out” Reagan as the thing in the world thename stands for. It may help to think of the sense as some descriptivecondition satisfied uniquely by Reagan (and not to think any moreabout what is meant by a descriptive condition). Complex linguisticexpressions are also associated with senses. And Frege held that thesense of a complex expression is a function of the senses of itssimple parts and how they are put together. Frege called propositionsthoughts (Gedanken), and held that the thought/proposition expressedby a sentence is itself a sense. And, like the senses of other complexlinguistic expressions, the proposition/thought expressed by asentence is a function of the senses of the words in the sentence andhow they are put together. Now Frege at least sometimes appears tohold the stronger view that the sense of a sentence(proposition/thought) has as constituents the senses of the words inthe sentence. And as the following quotation shows, his account of howthese sense-constituents are held together in the proposition/thoughtdepends on different kinds of linguistic expressions having differentkinds of senses:

For not all parts of a thought can be complete; at least one must be‘unsaturated’, or predicative; otherwise they would nothold together. For example, the sense of the phrase ‘the number2’ does not hold together with that of the expression ‘theconcept prime number ‘ without a link. We apply such a link inthe sentence ‘the number 2 falls under the concept primenumber’; it is contained in the words ‘falls under’,which need to be completed in two ways—by a subject and anaccusative; and only because their sense is thus‘unsaturated’ are they capable of serving as a link.(Frege [1892] p. 54)