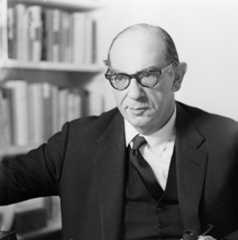

Isaiah Berlin, 18 July 1968

Photo by Helen Muspratt, Ramsey and Muspratt

© The Trustees of the Isaiah Berlin Literary Trust

Isaiah Berlin

Isaiah Berlin (1909–97) was a naturalised British philosopher,historian of ideas, political theorist, educator, public intellectualand moralist, and essayist. He was renowned for his conversationalbrilliance, his defence of liberalism and pluralism, his opposition topolitical extremism and intellectual fanaticism, and his accessible,coruscating writings on people and ideas. His essayTwo Conceptsof Liberty (1958) contributed to a revival of interest inpolitical theory in the English-speaking world, and remains one of themost influential and widely discussed texts in that field: admirersand critics agree that Berlin’s distinction between positive andnegative liberty remains, for better or worse, a basic starting pointfor discussions of the meaning and value of political freedom. Laterin his life, the greater availability of his numerous essays began toprovoke increasing interest in his work, particularly in the idea ofvalue pluralism; that Berlin’s articulation of value pluralismcontains many ambiguities and even obscurities has only encouragedfurther work on this rich and important topic by otherphilosophers.

- 1. Life

- 2. Philosophy of Knowledge and the Humanities

- 3. The History of Ideas

- 4. Ethical Thought and Value Pluralism

- 5. Political Thought

- 6. Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Academic Tools

- Other Internet Resources

- Related Entries

1. Life

Isaiah Berlin was born in 1909 in Riga (then capital of the Govenorateof Livonia in the Russian Empire, now capital of Latvia), the onlysurviving child (after a stillborn daughter) of Mendel Berlin, aprosperous Russian Jewish timber merchant, and his wife Marie,née Volshonok. In 1915 the family moved to the forestry town ofAndreapol (then in Russia’s Pskov Govenorate), and in 1916 toPetrograd (now St Petersburg), where they remained through bothRussian Revolutions of 1917, which Isaiah would remember witnessing.Despite early harassment by the Bolsheviks, the family was permittedto return to Riga with Latvian citizenship in 1920; from there theyemigrated, in 1921, to Britain. They lived first in suburban and thenin central London; Isaiah attended St Paul’s School and CorpusChristi College, Oxford, where he studied Greats (classical languages,ancient history, and philosophy) and PPE (philosophy, politics andeconomics), taking Firsts in both. In 1932 he was appointed to alectureship at New College, and shortly afterwards became the firstJew to be elected to a Prize Fellowship at All Souls, considered oneof the highest accolades in British academic life.

Throughout the 1930s Berlin was deeply involved in the development ofwhat became known as Oxford philosophy, or ordinary languagephilosophy; his friends and colleagues included J. L. Austin, A. J.Ayer and Stuart Hampshire, all of whom met regularly (with others) inBerlin’s rooms to discuss philosophy. However, he also evincedan early interest in a more historical approach to philosophy, and insocial and political theory, reflected in his lectures and reviews ofthe 1930s, as well as in his intellectual biography of Karl Marx(1939), still in print, in its fifth edition (2013), over eighty yearslater.

During the Second World War Berlin served in British InformationServices in New York City (1940–2) and at the British Embassy inWashington, DC (1942–6), where he was responsible for draftingweekly reports on the American political scene. For four months in1945–6 he visited the Soviet Union: his meetings there withsurviving but persecuted members of the Russian intelligentsia,particularly the poets Anna Akhmatova and Boris Pasternak, reinforcedhis staunch opposition to Communism, and had a formative influence onhis future intellectual agenda. After the war he returned to Oxford.Although he continued to teach and write on philosophy throughout thelater 1940s and into the early 1950s, his interests had shifted to thehistory of ideas, particularly Russian ideas, Marxist and othersocialist theories, and the Enlightenment and its critics. He alsobegan to publish widely-read articles on contemporary political andcultural trends, political ideology, and the internal workings of theSoviet Union. In 1950, election to a research fellowship at All Soulsallowed him to devote himself more fully to his historical, politicaland literary interests, which lay well outside the mainstream ofphilosophy as it was then practised and taught at Oxford. He was,however, one of the first of the founding generation of Oxfordphilosophers to make regular visits to American universities, andplayed an important part in spreading ‘Oxford philosophy’to the USA.

In 1957, a year after he had married Aline Halban (née deGunzbourg), Berlin was elected Chichele Professor of Social andPolitical Theory at Oxford (his inaugural lecture, delivered in 1958,wasTwo Concepts of Liberty). Later in 1957 he was knighted.He resigned his chair in 1967, the year after becoming foundingPresident of Wolfson College, Oxford (which he essentially created), apost from which he retired in 1975. In his later years he hoped towrite a major work on the history of European Romanticism, but thishope was unfulfilled. From 1966 to 1971 he was also a visitingProfessor of Humanities at the City University of New York, and heserved as President of the British Academy from 1974 to 1978.Collections of his writings, edited by Henry Hardy (sometimes with aco-editor), began appearing in 1978: there are, to date, fourteen suchvolumes (plus new editions of four works published previously byBerlin), as well as an anthology,The Proper Study ofMankind, and a four-volume edition of his letters. Berlinreceived the Agnelli, Erasmus and Lippincott Prizes for his work onthe history of ideas, and the Jerusalem Prize for his lifelong defenceof civil liberties, as well as numerous honorary degrees. He died in1997.

1.1 Intellectual Development

An early influence on Berlin was a waning British Idealism, asexpounded by T. H. Green, Bernard Bosanquet and F. H. Bradley. Whilean undergraduate, Berlin was converted to the Realism of G. E. Mooreand John Cook Wilson. By the time he began teaching philosophy he hadjoined a new generation of rebellious empiricists, some of whom (mostnotably A. J. Ayer) embraced the logical positivist doctrines of theVienna Circle and Wittgenstein’s earlier writings. AlthoughBerlin was always sceptical towards logical positivism, its suspicionof metaphysical claims and its preoccupation with the nature andauthority of knowledge strongly influenced his early philosophicalenquiries. These, combined with his historical bent, led him back tothe study of earlier British empiricists, particularly Berkeley andHume, on whom he lectured in the 1930s and late 1940s, and about whomhe contemplated writing books (which never materialised).

Berlin was also influenced by Kant and his successors. His firstphilosophical mentor was an obscure Russian Jewish Menshevikémigré named Solomon Rachmilevich, who had studiedphilosophy at several German universities, and who introduced Berlinto the great ideological quarrels of Russian history, as well as tothe history of German philosophy since Kant. Later, at Oxford, R. G.Collingwood fostered Berlin’s interest in the history of ideas,introducing him in particular to such founders of historicism asGiambattista Vico and J. G. Herder. Collingwood also reinforcedBerlin’s belief – heavily influenced by Kant – inthe importance to human life of the basic concepts and categories interms of which human beings organise and analyse their experience (seefurther 2.1 and note 2).

While working on his biography of Marx in the mid 1930s, Berlin cameacross the works of two Russian thinkers who would be importantinfluences on his political and historical outlook. One of these wasAlexander Herzen, who became a hero, and to whom Berlin wouldsometimes attribute many of his own beliefs about history, politicsand ethics. The other was the Russian Marxist publicist and historianof philosophy G. V. Plekhanov. Despite his opposition to Marxism,Berlin admired and praised Plekhanov both as a man and as a historianof ideas. It was initially by reading Plekhanov’s writings thatBerlin became interested in the naturalistic, empiricist andmaterialist thinkers of the Enlightenment, as well as their Idealistand historicist critics. Both Herzen and Plekhanov fuelledBerlin’s absorption in the political debates of nineteenth- andearly twentieth-century Russian liberals and radicals of variousstripes, which in turn informed his concern with both the philosophyof history and the ethics of political action.

During the Second World War, separated from his Oxford philosophicalbrethren, and exposed to political action, Berlin began to drift awayfrom his early philosophical concerns. His doubts were encouraged by ameeting with the Harvard logician H. M. Sheffer, who asserted thatgenuine increase in knowledge was possible only in such hybridsubfields of philosophy as logic and psychology. His meeting withSheffer led Berlin to realise that he lacked the passion and thebelief in his own ability to continue pursuing pure philosophy. Heconcluded that as a professional philosopher (as he then understoodthat role) he would make no original contributions, and would end hislife knowing no more than he did when he began. He thereforedetermined to switch to the history of ideas, in which (he believed)originality was less essential, and which would allow him to learnmore than he already knew. Berlin’s approach to the history ofideas would, however, remain deeply informed by his philosophicalpersona, as well as by his political beliefs. His historical work was,in effect, the practice of philosophy in a historical key.

By the early 1950s Berlin’s central beliefs had crystallisedfrom the confluence of his philosophical preoccupations, historicalstudies, and political and moral commitments and anxieties; and hismajor ideas were either already fully formed, or developing. Suchessays of the late 1950s asTwo Concepts of Liberty served asthe occasion for a synthesis and solidification of his thoughts.Berlin had always been a liberal; but from the early 1950s the defenceof liberalism became central to his intellectual concerns. Thisdefence was, characteristically, closely related to his moral beliefsand to his preoccupation with the nature and role of values in humanlife. In the early 1960s Berlin’s focus moved from the morepolitical concerns that occupied him in the 1950s to an examination ofthe nature of the humanities. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s he wasworking on the history of ideas, and from the mid 1960s nearly all ofhis writings took the form of essays in this field, particularly onthe Romantic and reactionary critics of the Enlightenment. In thefinal decades of his life Berlin continued to refine and re-articulatehis ideas, and particularly his formulation of pluralism; but hiscourse was set, and he appears to have been little affected by laterintellectual developments.

2. Philosophy of Knowledge and the Humanities

2.1 Conception of Philosophy

Berlin’s conception of philosophy was shaped by his earlyexposure to, and rejection of, both Idealism and logical positivism.[1] With the former he associated an excessively exalted view ofphilosophy as the ‘queen of the sciences’, capable ofestablishing fundamental, necessary, absolute, universal truths. Withthe latter he associated the reductionist and deflationary view ofphilosophy as, at best, a handmaiden to the sciences, and at worst asign of intellectual immaturity bred of scientistic confusion andcredulity.

Berlin’s approach combined a sceptical empiricism withneo-Kantianism to offer a defence of philosophy. Like Vico and WilhelmDilthey, as well as neo-Kantians such as Heinrich Rickert and WilhelmWindelband, Berlin insisted on the fundamental difference between thesciences and the humanities. He classed philosophy among thehumanities, but even there its status was unique. Those working inother fields aimed to discover authoritative methods for acquiringknowledge of the subjects to which they were devoted. Philosophy,however, was for Berlin concerned with questions which not only couldnot at present be answered, but for which no clearly proper method ofdiscovering an answer was known (see e.g. ‘The Purpose ofPhilosophy’ in 1978b and 2000a).

In the case of non-philosophical questions, even if the answer isunknown, the means for discovering the answer is known, or accepted,by most people. Thus questions of empirical fact can be answered byobservation. Other questions can be answered deductively, by referringto established rules: this is the case, for example, with mathematics,grammar and formal logic. For example, even if we do not know thesolution to a difficult mathematical problem, we do know the rules andtechniques that should lead us to the answer.

According to Berlin, philosophy concerns itself with questions of aspecial, distinctive character. To such questions not only are theanswers not known, but neither are the means for arriving at answers,or the standards of judgement by which to evaluate a suggested answer.Thus the questions ‘How long does it take to drive fromx toy?’ or ‘What is the cube root of729?’ are not philosophical; while ‘What is time?’or ‘What is a number?’ are. ‘What is the purpose ofhuman life?’ or ‘Are all men brothers?’ arephilosophical questions, while ‘Do most of such-and-such a groupof men think of one another as brothers?’ or ‘What didLuther believe was the purpose of life?’ are not.

Berlin related this view to Kant’s distinction between mattersof fact and those conceptual structures and categories that we use tomake sense of facts. Philosophy, being concerned with questions thatarise from our attempts to make sense of our experiences, involvesconsideration of the concepts and categories through which experienceis perceived, organised and explained.

While Kant saw these organising categories as fixed and universal,Berlin believed that they are, to different degrees, varying,transient or malleable. ‘All our categories are, in theory,subject to change’ (2002b, 144, note 1). No categories arewholly prior to, or independent of, experience, even though inpractice some of them are pragmatically fixed, whether by the world orby our minds or both. Rather, the ideas in terms of which we makesense of the world are closely tied up with our experiences: theyshape those experiences, and are shaped by them, and as experiencevaries from one time and place to another, so do basic concepts.[2] Recognition of the basic concepts and categories of human experiencediffers both from the acquisition of empirical information and fromdeductive reasoning, for the categories are logically prior to,presupposed by, both.

Philosophy, then, is the study of the ‘thought-spectacles’through which we view the world; and since at least some of thesechange over time, at least some philosophy is necessarily historical.Because these categories are so important to every aspect of ourexperience, philosophy – even if it is always tentative andoften seems abstract and esoteric – is a crucially importantactivity, which responds to the vital, ineradicable human need todescribe and explain the world of experience.

Berlin insisted on philosophy’s social usefulness, howeverindirect and unobtrusive.[3] By bringing to light often subconscious presuppositions and models,and scrutinising their validity, philosophy identifies errors andconfusions that lead to misunderstanding, distort experience, and thusdo real harm. Because philosophy calls commonly accepted assumptionsinto question, it is inherently subversive, opposed to all orthodoxy,and often troubling; but this is inseparable from what makesphilosophy valuable, and indeed indispensable, as well as liberating.Philosophy’s goal, Berlin concluded, was ‘to assist men tounderstand themselves and thus operate in the open, and not wildly, inthe dark’ (1978b, 14).

2.2 Basic Propositions: Epistemology, Metaphysics, Logic

Perhaps the most important work Berlin did in ‘pure’philosophy, in the light of his later ideas, concerned ‘logical translation.’[4] In his essay of that title (reprinted in 1978b), Berlin criticisedthe assumption that all statements, to be genuine and meaningful, orto claim correctness, must be capable of being translated into asingle, ‘good’ type of proposition, and asserted that theideal of a single proper type of proposition was illusory andmisleading. He identified two different, opposed approaches based onthis erroneous assumption. One was the ‘deflationary’approach, which sought to assimilate all propositions to one truetype. Thus, phenomenalism sought to translate all statements intoassertions about immediately perceived sense data. The other was the‘inflationary’ approach, which posited entitiescorresponding to all statements, thus ‘creating’ orasserting the existence of things that didn’t exist at all. Bothof these errors stemmed from a demand for a ‘forcibleassimilation’ of all propositions to a single type. Berlinsuggested that such a demand was based, not on a true perception ofreality, but rather on a psychological need for certainty, uniformityand simplicity, as well as what he termed the ‘IonianFallacy’, the assumption that everything is made out of, or canbe reduced to or understood in terms of, one and the same substance or type.[5]

Berlin insisted that there is no single criterion of meaningfulness,no absolutely incorrigible type of knowledge. The quest for certaintywas self-defeating: to restrict oneself to saying only that whichcould be said without any doubt or fear of being mistaken was tosentence oneself to silence. To say anything about the world requiresbringing in something other than immediate experience:

The vast majority of the types of reasoning on which our beliefs rest,or by which we should seek to justify them […], are notreducible to formal deductive or inductive schemata, or combinationsof them. […] The web is too complex, the elements too many andnot, to say the least, easily isolated and tested one by one;[…] we accept the total texture, compounded as it is out ofliterally countless strands – […] without thepossibility, even in principle, of any test for it in its totality.For the total texture is what we begin and end with. There is noArchimedean point outside it whence we can survey the whole andpronounce upon it. […] It is the sense of the general textureof experience […] that constitutes the foundation of knowledge,that is itself not open to inductive or deductive reasoning: for boththese methods rest upon it. (1978b, 149–50)

At the heart of Berlin’s philosophy was an awareness of theenormous variety and complexity of reality, which we can only begin tocomprehend: the many strands that make up human experience are‘too many, too minute, too fleeting, too blurred at the edges[to be integrated into a total picture of experience]. Theycriss-cross and penetrate each other at many levels simultaneously,and the attempt to prise them apart […] and pin them down, andclassify them, and fit them into their specific compartments, turnsout to be impracticable’ (1978b, 156).

These two closely related propositions – that absolute certaintyis an impossible ideal (Berlin once wrote that, if his work displayedany ‘single tendency’, it was a ‘distrust of allclaims to the possession of incorrigible knowledge about issues offact or principle in any sphere of human behaviour’: 1978a, x),and that not everything can or should be reduced or related to asingle ideal, model, theory or standard – might be consideredthe centrepieces of Berlin’s philosophy. They are central to hisview of language and knowledge; they are equally important to hisethics and his philosophy of the humanities. Also central to thesedifferent facets of his thought was Berlin’s emphasis on theimportance, and indeed priority, of particular things as objects ofknowledge and of individual people as moral subjects.

2.3 The Distinction between the Sciences and the Humanities

Berlin’s individualism, the influence on him of neo-Kantianism,and what one scholar (Allen 1998) has called his anti-Procrusteanism– his opposition to attempts dogmatically and inappropriately toimpose standards or models on aspects of human experience which theydon’t fit – shaped his view of what he usually referred toas the ‘humanities’ (sometimes as ‘humanestudies’) and their relationship to the (natural) sciences. By‘humanities’ he meant all disciplines concerned with thestudy of human conduct and experience – thus encompassing manyso-called ‘social sciences’ as well as the fields of studytraditionally classed as ‘humanities’ (see note 1).

Berlin criticised the positivist view of the sciences as theparadigmatic form of knowledge, which the humanities should measurethemselves by and seek to emulate. He argued that the humanitiesdiffered fundamentally from the sciences both in the nature of theirsubject matter (as Vico and Dilthey had maintained), and in the sortof knowledge that they sought (as Rickert insisted). As a result,different methods, standards and goals were appropriate to each.

Most obviously, the humanities study the world that human beingscreate for themselves and inhabit, while the sciences study thephysical world of nature. Why should this make a difference to the waythey are studied? One answer is that the two worlds are fundamentallydifferent in themselves. But Berlin preferred the argument that thehuman and natural worlds must be studied differently because of thediffering relationship between the observer or thinker and the objectof study. We study nature from without, culture from within. In thehumanities the scholar’s own ways of thinking, the fabric of hisor her life, every facet of his or her experience is part of theobject of study. The sciences, on the other hand, aim to understandnature objectively and dispassionately. The scientist must take aslittle for granted as possible, preferring hard evidence to‘common sense’ when they diverge. But in the humanitiesone cannot act in this manner: to study human life, it is necessary tobegin from our understanding of other human beings, of what it is tohave motives and feelings. Such understanding is based on our ownexperience, which in turn necessarily involves certain‘common-sense’ assumptions, which we use to fit ourexperience into patterns that make it explicable and comprehensible.These patterns may be more or less accurate; and we can judge theiraccuracy by seeing how well they fit experience as we know it. But wecannot divest ourselves entirely of the assumptions that underliethem. (The human world can also itself be a legitimate subject ofscientific study, of course, but only incompletely, by bracketing offwhat makes it distinctive. Cf. note 7.)

Berlin asserted that the humanities also differed from the sciences inthat the former were concerned with understanding the particulars ofhuman life in and of themselves, while the sciences sought toestablish general laws which could explain whole classes of phenomena.The sciences are concerned with types, the humanities withindividuals. Scientists concentrate on similarities and look forregularities; at least some practitioners of the humanities –historians, in particular – are interested in differences. To bea good historian requires a ‘concentrated interest in particularevents or persons or situations as such, and not as instances of ageneralisation’ (1978b, 180). The humanities should not aim toemulate the sciences by seeking laws to explain or predict humanactions, but should concern themselves with understanding everyparticular human phenomenon in its uniqueness. In the case of ascience we think it more rational to put our trust in general lawsthan in specific phenomena; in the case of the humanities, theopposite is true. If someone claims to have witnessed a phenomenonthat contradicts well-established laws of science, we seek anexplanation that will reconcile that perception with science; if noneis possible, we may conclude that the witness is deceived. In the caseof history we do not usually do this: we look at particular phenomenaand seek to explain them in themselves.[6] There are, Berlin claimed, ‘more ways than one to defyreality’. It is unscientific to ‘defy, for no good logicalor empirical reason, established hypotheses and laws’. But it isunhistorical, on the other hand, to ‘ignore or twist one’sview of particular events, persons, predicaments in the name of laws,theories, principles derived from other fields, logical, ethical,metaphysical, scientific, which the nature of the medium rendersinapplicable’ (1978b, 185).

Berlin emphasised the importance to a sense of history of the idea ofits ‘one-directional’ flow (ibid., 144). This sense ofhistorical reality makes it seem not merely inaccurate, butimplausible, and indeed ridiculous, to suggest, for example, thatHamlet was written in the court of Genghis Khan (ibid., 142,175). The historical sense involves, not knowledge of what happened– this is acquired by empirical means – but a sense ofwhat is plausible and implausible, coherent and incoherent, inaccounting for human action (1978b, 183). There is no a priorishortcut to such knowledge. Historical thinking is much more like theoperation of common sense, involving the weaving together of variouslogically independent concepts and propositions, and bringing them tobear on a particular situation as best we can, than like theapplication of laws or formulae. The ability to do this is a knack– judgement, or a sense of reality (1978b, 152).

Understanding of history is based on knowledge of humanity, which isderived from direct experience, consisting not merely ofintrospection, but of interaction with others. This is the basis forVerstehen, or imaginative understanding: the‘recognition of a given piece of behaviour as being part andparcel of a pattern of activity which we can follow, […] andwhich we describe in terms of the general laws which cannot possiblyall be rendered explicit (still less organised into a system), butwithout which the texture of normal human life – social orpersonal – is not conceivable’ (1978b, 168). The challengeof history is the need for the individual to go beyond his or her ownexperience, which is the basis of his or her ability to conceive ofhuman behaviour. We must reconstruct the past not only in terms of ourown concepts and categories, but in terms of how past events must havelooked to those who participated in them. The practice of history thusrequires gaining knowledge of what consciousness was like for otherpersons, in situations other than our own, through an‘imaginative projection of ourselves into the past’ inorder to ‘capture concepts and categories that differ from thoseof the investigator by means of concepts and categories that cannotbut be his own. […] Without a capacity for empathy andimagination beyond any required by a physicist, there is no vision ofeither past or present, neither of others nor of ourselves’(1978b, 177–8). Historical reconstruction and explanationinvolves ‘entering into’ the motives, principles, thoughtsand feelings of others; it is based on a capacity for knowing likethat of knowing someone’s character or face (1978b,173–5).

2.4 Free Will and Determinism

The sort of historical understanding that Berlin sought to depict was‘related to moral and aesthetic analysis’. It conceives ofhuman beings not merely as organisms in space, but as ‘activebeings, pursuing ends, shaping their own and others’ lives,feeling, reflecting, imagining, creating, in constant interaction andintercommunication with other human beings; in short, engaged in allthe forms of experience that we understand because we share in them,and do not view them purely as external observers’ (1978b,173–4). For Berlin, the philosophy of history was tied not onlyto epistemology, but to ethics. The best-known and most controversialfacet of his writings on the relationship of history to the scienceswas his discussion of the problem of free will and determinism, whichin his hands took on a distinctly moral cast.[7] InHistorical Inevitability Berlin radically questioneddeterminism (the view that human beings do not possess free will, thattheir actions and indeed thoughts are predetermined by impersonalforces beyond their control) and historical inevitability (the viewthat all that occurs in the course of history does so because it must,that history pursues a particular course which cannot be altered, andwhich can be discovered, understood and described through laws ofhistorical development).

Berlin did not assert that determinism was untrue, but rather that toaccept it required a radical transformation of the language andconcepts we use to think about human life – especially arejection of the idea of individual moral responsibility. To praise orblame individuals, to hold them responsible, is to assume that theyhave some control over their actions, and could have chosendifferently. If individuals are wholly determined by unalterableforces, it makes no more sense to praise or blame them for theiractions than it would to blame someone for being ill, or praisesomeone for obeying the laws of gravity. Indeed, Berlin furthersuggested that acceptance of determinism – that is, the completeabandonment of the concept of human free will – would lead tothe collapse of all meaningful rational activity as we know it.

This is an extension into the realm of the understanding of humanbeings of Kant’s ‘Copernican’ revolution (to useKant’s own epithet). Kant gave full recognition, for the firsttime, to the inescapable contribution made by our minds to graspingthe non-human world; Berlin mirrors this move with a scarcely lessfundamental claim of his own, that there are equally inescapable waysin which, at any given time or at all times known to us, we cannot butthink of and understand the behaviour and experience of our ownkind.

The basic categories (with their corresponding concepts) in terms ofwhich we define men – such notions as society, freedom, sense oftime and change, suffering, happiness, productivity, good and bad,right and wrong, choice, effort, truth, illusion (to take them whollyat random) – are not matters of induction and hypothesis. Tothink of someone as a human being isipso facto to bring allthese notions into play; so that to say of someone that he is a man,but that choice, or the notion of truth, mean nothing to him, would beeccentric: it would clash with what we mean by ‘man’ notas a matter of verbal definition (which is alterable at will), but asintrinsic to the way in which we think, and (as a matter of‘brute’ fact) evidently cannot but think. (CC2 217)

Here ‘freedom’ means the centrally important concept offree will. We cannot help experiencing human behaviour as causallyundetermined and freely chosen. That we have free will is not ascientific hypothesis, but a precondition of our experience ofhumanity, to abandon which would leave our world-view in ruins.(Whether this entails that determinism is false is a further question,which Berlin does not fully confront; nor do we pursue it here.)

Berlin also insisted that belief in historical inevitability wasinspired by psychological needs, and not required by known facts; andthat it had dangerous moral and political consequences, justifyingsuffering and undermining respect for the ‘losers’ ofhistory. A belief in historical inevitability served as an‘alibi’ for evading responsibility and blame, and forcommitting enormities in the name of necessity or reason. It providedan excuse both for acting badly and for not acting at all.[8]

Berlin’s insistence on the importance of the idea of free will,and the incompatibility of consistent and thoroughgoing determinismwith our basic sense of ourselves and our experience as human beings,was closely tied to his liberalism and pluralism, with their emphasison the importance, necessity and dignity of individual choice. Thisinsistence involved him in a number of debates with other philosophersand historians in the 1950s and early 1960s, and helped to provoke aspate of writing in the English-speaking world on the philosophy ofhistory, which might otherwise have languished.

Also controversial was Berlin’s claim that the writing andcontemplation of history necessarily involves moral evaluation. He didnot, as some of his critics charged (e.g. Carr 1961), mean this as acall for moralising on the part of historians. Berlin’s argumentwas that, first, our normal way of regarding human beings as agentswho make choices necessarily involves moral evaluation; to eliminatemoral evaluation from our thinking completely would be to alterradically the way that we view the world. Nor would such an alterationtruly move beyond moral evaluation; for strenuous attempts to bemorally neutral are themselves motivated by a moral commitment to theideal of impartiality. Furthermore, given the place of moralevaluation in ordinary human thought and speech, an account couched inmorally neutral terms will fail accurately to reflect the experienceor self-perception of the historical actors in question. This lastargument was particularly important to Berlin, who believed thathistorical writing should reflect and convey past actors’understanding of their situation, so as to provide explanations ofwhy, thinking as they did, they acted as they did. He thereforeinsisted that the historian must attend to the moral claims andperceptions underlying historical events.

3. The History of Ideas

Berlin’s emphasis on the subversive, liberating, anti-orthodoxnature of philosophy was accompanied by a particular interest inmoments of radical change in the history of ideas, and in original,heterodox and often marginal thinkers, while his emphasis on thepractical consequences of ideas led him to focus on thosetransformations and challenges which, in his view, had wroughtparticularly decisive changes in people’s moral and politicalconsciousness, and in their behaviour. Finally, his concern with theconflicts of his own day led him to concentrate mainly on modernintellectual history, and to trace the emergence of certain ideas thathe regarded as particularly important, for good or ill, in thecontemporary world.[9]

Many of Berlin’s writings on the history of ideas were connectedto his philosophical work, and to one another, in their examination ofcertain overarching themes. These included the relationship betweenthe sciences and the humanities; the philosophy of history; theorigins of nationalism and socialism; the revolt against what Berlincalled ‘monism’ in general, and scientism in particular,in the early nineteenth century and thereafter; and the vicissitudesof ideas of liberty.

The narrative of the history of ideas that Berlin developed andrefined over the course of his works began with the Enlightenment, andfocused on the initial rebellion against what he regarded as thatepoch’s dominant assumptions.[10]

In Berlin’s account, the thinkers of the Enlightenment believedhuman beings to be naturally either benevolent or malleable. Thiscreated a tension within Enlightenment thought between the view thatnature dictates human ends, and the view that nature provides more orless neutral material, to be moulded rationally and benevolently(ultimately the same thing) by conscious human interventions –education, legislation, rewards and punishment, the whole apparatus of society.[11] Berlin also attributed to the Enlightenment the beliefs that allhuman problems, both of knowledge and ethics, can be resolved throughthe discovery and application of the proper method (generally reason,the conception of which was based on the methods of the sciences,particularly Newtonian physics); and that genuine human goods andinterests were ultimately compatible, so that conflict, likewickedness, was the result of ignorance, misunderstanding, ordeception and oppression practiced by corrupt authorities(particularly the Church).[12]

Berlin saw the school (or schools) of thought that began to emergeshortly before the French Revolution, and became ascendant during andafter it, as profoundly antagonistic towards the Enlightenment. He wasmost interested in German Romanticism, but also looked at othermembers of the larger tendency he referred to as the ‘Counter-Enlightenment’.[13] Berlin’s account sometimes focused on a attack on theEnlightenment’s benevolent and optimistic liberalism bynationalists and reactionaries; sometimes on the rejection of moraland cultural universalism by champions of cultural particularism andpluralism; and sometimes on the critique of naturalism and scientismby thinkers who advocated a historicist view of society as essentiallydynamic, shaped not by the laws of nature, but by the unlawlike,purposeless contingencies of history.

Berlin has been viewed both as an adherent of the Enlightenment whoshowed a fascination, whether eccentric or admirable, with itscritics; and as a critic and even opponent of the Enlightenment, whofrankly admired its enemies. There is some truth in both of thesepictures, neither of which does justice to the complexity ofBerlin’s views. Berlin admired many of the thinkers of theEnlightenment, and explicitly regarded himself as ‘on theirside’ (Jahanbegloo 1992, 70); he believed that much of what theyhad accomplished had been for the good; and, as an empiricist, herecognised them as part of the same philosophical tradition to whichhe belonged. But he also believed that they were wrong, and sometimesdangerously so, about some of the most important questions of society,morality and politics. He regarded their psychological and historicalvision as shallow, excessively uniform, and naive; and he traced tothe Enlightenment a technocratic, managerial view of human beings andpolitical problems to which he was profoundly opposed, and which, inthe late 1940s and early 1950s, he regarded as one of the gravestdangers facing the world.

Berlin regarded the Enlightenment’s critics as in many waysdangerous and deluded. He attacked or dismissed their metaphysicalbeliefs, particularly the philosophies of history of Hegel and hissuccessors. He was also wary of the aesthetic approach to politicsthat many Romantics had practised and fostered. And, whileappreciative of some elements in the Romantic conception of liberty,he saw Romanticism’s influence on the development of the idea ofliberty as largely perverting. But at the same time he thought theEnlightenment’s opponents had pointed to many important truthsthat the Enlightenment had neglected or denied, both negative (thepower of unreason, and particularly the darker passions, in humanaffairs) and positive (the inherent value of variety and of personalvirtues such as integrity and sincerity, and the centrality to humannature and dignity of the capacity for choice). Romanticism rebelledin particular against the constricting order imposed by reason, andchampioned the human will. Berlin was sympathetic to this stance, butalso believed that the Romantics had gone too far both in theirprotests and in their celebrations. He remained committed to the goalof understanding the world so as to be able to ‘act rationallyin it and on it’ (1990, 2). His interest in critics of theEnlightenment reflected both curiosity about the views of those withwhom he often disagreed, and a desire to learn from the most acutechallenges to a progressive, ‘liberal rationalist’[14] (Jahanbegloo 1992, 70) or ‘rational-liberal’ (Berlin2006a, 104) position, so as to appreciate, and repair, itsshortcomings and vulnerabilities. Berlin’s own articulation ofliberalism and pluralism attempted to integrate a defence of theEnlightenment’s legacy with the insights of its critics.

4. Ethical Thought and Value Pluralism

The republication of Berlin’s numerous essays in thematiccollections, beginning withFour Essays on Liberty (1969) andVico and Herder (1976), and continuing at an increased pacefrom 1978 under the general (and mostly specific) editorship of HenryHardy, served to highlight as a central dimension of Berlin’sthought his advocacy of the doctrine of value pluralism (which hehimself called ‘pluralism’). Increasingly from the early1990s value pluralism has come to be seen by many as Berlin’s‘master idea’, and has become the most discussed, mostadmired and most controversial of his ideas.

Value pluralism was indeed at the centre of Berlin’s ethicalthought; but there is more to that thought than value pluralism alone.Berlin defined ethical thought as ‘the systematic examination ofthe relations of human beings to one another, the conceptions,interests and ideals from which human ways of treating one anotherspring, and the systems of value on which such ends of life arebased’. These systems of value are ‘beliefs about how lifeshould be lived, what men and women should be and do’ (1990,1–2). Just as Berlin’s conception of philosophy was basedon a belief about the important role of concepts and categories inpeople’s lives, his conception of ethics was founded on hisbelief in the importance of normative or ethical concepts andcategories – especially values.[15]

Berlin did not set out a systematic theory about the nature of values,and so his view must be gleaned from his writings on the history ofideas. His remarks on the status and origins of values are ambiguous,though not necessarily irreconcilable with one another. He seems,first, to endorse the Romantic view – which he traces to Kant(although he also sometimes attributes it to Hume) – that valuesare not discovered ‘out there’, as‘ingredients’ in the universe, not deduced or derived fromnature. Rather, they are human creations, and derive their authorityfrom this fact. From this followed a theory of ethics according towhich individual human beings are the most morally valuable things, sothat the worth of ideals and actions should be judged in relation tothe meanings and impact they have for and on such individuals. Thisview underlay Berlin’s passionate conviction of the error oflooking to theories rather than human realities, of the evil ofsacrificing living human beings to abstractions (which he foundemphasised in Herzen); it also related to Berlin’s theory ofliberty, and his belief in liberty’s special importance.

At other times Berlin seems to advance what amounts almost to a theoryof natural law, albeit in minimalist, empirical dress. In such caseshe suggests that there are certain unvarying features of human beings,as they have been constituted throughout recorded history, that makecertain values important, or even necessary, to them. Values, then,would be beliefs about what it is good to be and do – about whatsort of life, what sort of character, what sort of actions, what stateof being it is desirable, given human nature, for us to aspire to.This view of the origin of values also comes into play inBerlin’s defence of the value of liberty, when he suggests thatthe freedom to think, to enquire, to imagine, and above all to choose,without constraint or fear, is valuable because human beings need suchmental freedom; to deny it to them is a denial of their nature,imposes an intolerable burden, and at the extreme entirely dehumanisesthem.

In an attempt to reconcile these two strands, one might say that, forBerlin, the values that humans create are rooted in the nature of thebeings who pursue them. But this is simply to move the question back astep, for the question then immediately arises: Is this human naturenatural and fixed, or created and altered over time through consciousor unconscious human action? Berlin’s answer (see e.g. 1990,319–23) comes in two parts. He rejects the idea of a fixed,fully specified human nature, regarding natural essences withsuspicion. Yet he does believe (however under-theorised, unsystematicand undogmatic this belief may be) in boundaries to, and requirementsmade by, human nature as we know it. This common human nature may notbe fully specifiable in terms of a list of unvarying characteristics;but, while many characteristics may vary from individual to individualor culture to culture, there is a limit on the variation – justas the human face may vary greatly from person to person in many ofits properties, while remaining recognisably human, but at the sametime it is possible to distinguish between a human and a non-humanface, even if the difference between them cannot be reduced to aformula. Indeed, at the core of Berlin’s thought was hisinsistence on the importance of humanity, or the distinctively human,both as a quasi-Kantian category and as a moral reality, which doesnot need to be reduced to an unvarying essence in order to havedescriptive and normative force.

There is a related ambiguity about whether values are objective orsubjective. One might conclude from Berlin’s view of values ashuman inventions that he would regard them as subjective. Yet heinsisted, on the contrary, that values are objective, even going sofar as to label his position ‘objective pluralism’ (2015,210; 2000b, 245, note 1). Yet it is unclear what exactly he meant bythis, or how this belief relates to his view of values as humancreations. There are at least two accounts of the objectivity ofvalues that can be plausibly attributed to Berlin. The first is thatvalues are ‘objective’ in that they are simply facts aboutthe people who hold them – so that, for instance, liberty is an‘objective’ value because I value it, and would feelfrustrated and miserable without at any rate a minimal amount of it.The second is that the belief in or pursuit of certain values is theresult of objective realities of human nature – so that, forinstance, liberty is an ‘objective’ value because certainfacts about human nature make liberty good and desirable for humanbeings. These views are not incompatible with one another, but theyare distinct; and the latter provides a firmer basis for the minimalmoral universalism that Berlin espoused.

Finally, Berlin insisted that each value is binding on human beings byvirtue of its own claims, in its own terms, and not in terms of someother value or goal, let alone the same value in all cases. This viewwas one of the central tenets of Berlin’s pluralism.

4.1 Berlin’s Definition of Value Pluralism

Berlin’s development and definition of pluralism both begannegatively, with the identification of the opposing position, which heusually referred to as ‘monism’, and sometimes as‘the Ionian fallacy’ or ‘the Platonic ideal’.His definition of monism may be summarised as follows:

- All genuine questions must have one true answer, and one only; allother responses are errors.

- There must be a dependable path to discovering the true answer toa question, which is in principle knowable, even if currentlyunknown.

- The true answers, when found, will be compatible with one another,forming a single whole; for one truth cannot be incompatible withanother. (This, in turn, is based on the assumption that the universeis harmonious and coherent.)

We have seen that Berlin denied that the first two of theseassumptions are true. In his ethical pluralism he pushed these denialsfurther, and added a forceful denial of the third assumption.According to Berlin’s pluralism, genuine values are many. Theymay – and often do – come into conflict with one another.When two or more values clash, it is not because one or another hasbeen misunderstood; nor can it be said, a priori, that any one valueis always more important than another. Liberty can conflict withequality or with public order; mercy with justice; love withimpartiality and fairness; social and moral commitment with thedisinterested pursuit of truth or beauty (the latter two values,contra Keats, may themselves be incompatible); knowledge withhappiness; spontaneity and free-spiritedness with dependability andresponsibility. Conflicts of values are ‘an intrinsic,irremovable element in human life’; ‘the notion of totalhuman fulfilment is a […] chimera’. ‘Thesecollisions of values are of the essence of what they are and what weare’; a world in which such conflicts are resolved is not theworld we know or understand (2002b, 213; 1990, 13).

Berlin further asserted that values may be not only incompatible, butincommensurable. There has been considerable controversy over what hemeant by this, and whether his understanding of incommensurability waseither correct or coherent. In speaking of the incommensurability ofvalues, Berlin seems to have meant that there is no common measure, no‘common currency’ in terms of which the relativeimportance of any two values can be established in the abstract. Thusone basic implication of pluralism for ethics is the view that aquantitative approach to ethical questions (such as that envisaged byUtilitarianism) is impossible. In addition to denying the existence ofa common currency for comparison, or a governing principle (such asthe utility principle), value incommensurability holds that there isno general procedure for resolving value conflicts – there isnot, for example, a lexical priority rule (that is, no value alwayshas priority over another).

Berlin based these assertions on empirical grounds – on‘the world that we encounter in ordinary experience’, inwhich ‘we are faced with choices between ends equally ultimate,and claims equally absolute,[16] the realisation of some of which must inevitably involve thesacrifice of others’ (2002b, 213–14). Yet he also heldthat the doctrine of pluralism reflected logically necessary ratherthan contingent truths about the nature of human moral life and thevalues that are its ingredients. The idea of a perfect whole orultimate solution is not only unattainable in practice, but alsoconceptually incoherent. To avert or overcome conflicts between valuesonce and for all would require the transformation, which amounted tothe abandonment, of those values themselves. It is not clear that thislogical point adds anything significant to the empirical point abouthuman ends recorded in the last quotation, but we do not pursue thisdoubt here.

Berlin’s pluralism was not free-standing: it was modified andguided by other beliefs and commitments. One of these, discussedbelow, was liberalism. Another was humanism – the view thathuman beings are of primary importance, and that avoiding harm tohuman beings is the first moral priority (Aarsbergen-Ligtvoet 2006;Cherniss and Hardy 2018). Berlin therefore held that, in navigatingbetween conflicting values, ‘The first public obligation is toavoid extremes of suffering.’ He insisted that moral collisions,even if unavoidable, can be softened, claims balanced, compromisesreached. The goal should be the maintenance of a ‘precariousequilibrium’ that avoids, as far as possible, ‘desperatesituations’ and ‘intolerable choices’. Philosophyitself cannot tell us how to do this, though it can help by bringingto light the problem of moral conflict and all of its implications,and by weeding out false solutions. But in dealing with conflicts ofvalues, ‘The concrete situation is almost everything’(1990, 18–19).

One of the main features of Berlin’s account of pluralism is theemphasis placed on the act of choosing between values. Pluralism holdsthat, in many cases, there is no single right answer. Berlin used thisas an argument for the importance of liberty (see note 25) – or,perhaps more precisely, an argument against the restriction of libertyin order to impose the ‘right’ solution by force. Berlinalso made a larger argument about making choices. Pluralism involvesconflicts, and thus choices, not only between particular values inindividual cases, but between ways of life. While Berlin seems tosuggest that individuals have certain inherent traits – anindividual nature, or character, which cannot be wholly altered orobscured – he also insisted that they make decisions about whothey will be and what they will do. Choice is thus both an expressionof an individual personality, and part of what makes that personality;it is essential to the human self.

4.2 Value Pluralism before Berlin

Berlin provided his own (inconsistent and somewhat peculiar)genealogies of pluralism. He found the first rebellion against monismeither in Machiavelli (1990, 7–9) or in Vico and Herder (2000a,8–11), who were also decisive figures in the first account. Yethe acknowledged that Machiavelli wasn’t really a pluralist, buta dualist; and other scholars have questioned his identification ofVico and Herder as pluralists, when both avowed belief in a higher,divine or mystical, unity behind variety. Other scholars have creditedother figures in the history of philosophy, such as Aristotle, withpluralism (Nussbaum 1986, Evans 1996). James Fitzjames Stephenadvanced something that looks very much like Berlin’s pluralism(Stephen 1873), though he allied it to a conservative critique ofMill’s liberalism.

In Germany, Dilthey came close to pluralism, and Max Weber presented adramatic, forceful picture of the tragic conflict betweenincommensurable values, belief systems and ways of life (Weber 1918,esp. 117, 126, 147–8, 151–3; cf. Weber 1904, esp.17–18).

Ethical pluralism first emerged under that name, however, in America,inspired by William James’s pluralistic view of the universe, aswell as his occasional gestures towards value pluralism (James 1891).John Dewey and the British theologian Hastings Rashdall bothapproximated pluralism in certain writings (Dewey 1908, Rashdall1907); but pluralism was apparently first proposed, under that name,and as a specifically ethical doctrine,in language strikingly similar to Berlin’s, by Sterling Lamprecht, a naturalist philosopher and scholar of Hobbesand Locke, in two articles (1920, 1921), as well as, somewhat later,by A. P. Brogan (1931). The dramatic similarities between not onlyBerlin’s and Lamprecht’s ideas, but also their language,make it difficult to believe that Lamprecht was not an influence onBerlin. However, there is no independent evidence that Berlin knewLamprecht’s work; and Berlin’s tendency was more often tocredit his own ideas to others than to claim the work of others as hisown.

Versions of pluralism were also advocated by Berlin’scontemporaries Raymond Aron, Stuart Hampshire, Reinhold Niebuhr andMichael Oakeshott (although Oakeshott seems to have attributedconflicts of values to a mistakenly reflective approach to ethicalissues, and suggested that they could be overcome through relying on amore habitual, less self-conscious, ethical approach: see Oakeshott1962, 1–36).

4.3 The Emergence of Value Pluralism in Berlin’s Work

Some of the elements of value pluralism are detectable inBerlin’s early essay ‘Some Procrustations’ (1930),published while he was still an undergraduate at Oxford. This essay,drawing on Aristotle, and focusing on literary and cultural criticismrather than philosophy proper, made the case for epistemological andmethodological, rather than ethical, pluralism. Berlin criticised thebelief in, and search for, a single method or theory, which couldserve as a master key for understanding all experience. He insistedthat, on the contrary, different standards, values and methods ofenquiry are appropriate for different activities, disciplines andfacets of life. In this can be seen the seeds of his later work on thedifferences between the sciences and the humanities, of his attacks onsystematic explanatory schemes, and of his value pluralism; but allthese ideas had yet to be developed or applied.

Berlin was further nudged towards pluralism by discovering what he sawas a suggestion by Nicolas Malebranche that simplicity and goodnessare incompatible (1680, e.g. 116–17, 128–30); this struckhim at the time as an ‘odd interesting view!’, but itstuck, and he became convinced of its central and pregnant truth(2004, 72).[17] Berlin set out his basic account of what he would later label monismin his biography of Marx (1939, 37), but did not explicitly criticiseit or set out a pluralistic alternative to it, although his lecture‘Utilitarianism’ (1937b), dating from the late 1930s, doesinclude an argument that anticipates his later claim that values areincommensurable. The basic crux of pluralism, and Berlin’sconnection of it to liberalism, is apparent in rough, telegraphic formin Berlin’s notes for his lecture ‘Democracy, Communismand the Individual’ (1949), and pluralism is also advanced in anaside, though not under that name, in ‘HistoricalInevitability’ (1954: see 2000b, 151). Berlin referred topluralism and monism as basic, conflicting attitudes to life in 1955(Berlin et al. 1955, 504). But his use of the term and his explicationof the concept did not fully come together, it appears, untilTwoConcepts of Liberty (1958; even then, his articulation ofpluralism is incomplete in the first draft of the essay).

Thereafter, variations on Berlin’s account of pluralism appearthroughout his writings on Romanticism. Late in his life, taking stockof his career, and trying to communicate what he felt to be his mostimportant philosophical insights, Berlin increasingly devoted himselfto the explicit articulation and refinement of pluralism as an ethicaltheory. He had referred in a private letter of 1968 (Ignatieff 1998,246) to ‘the unavoidability of conflicting ends’ as hisone genuine discovery. He devoted the lecture he gave in accepting theAgnelli Prize in 1988, ‘The Pursuit of the Ideal’, toexplaining what pluralism meant, and this remains the most eloquentand concentrated summary of pluralism. Berlin also discussed pluralismin many interviews and printed exchanges with other scholars from the1970s onward, in an attempt to work through the conflicts,controversies and confusions to which his ideas gave rise; but many ofthese resisted Berlin’s attempts at resolution, and continue tofigure in, and sometimes dominate, discussions of his work.

4.4 Value Pluralism after Berlin: Some Controversies

Since the 1990s, pluralism has become the most widely and hotlydebated of Berlin’s ideas. This is due in part to Berlin’swork, and in part to that of later philosophers who, as followers orallies of Berlin or independently, have also articulated and advancedvalue pluralism or similar positions.[18] Although pluralism achieved its current prominence in interpretationsof Berlin’s work later in his life, it was identified earlier asa key component in his thought by a few prescient readers. Two ofthese readers advanced what remains one of the most common criticismsof Berlin’s pluralism: that it is indistinguishable fromrelativism (Strauss 1961; Momigliano 1976; see MacCallum 1967a andKocis 1989 for other early critiques).[19]

One problem that has bedevilled the debate is a persistent failure todefine the terms at issue with adequate clarity and precision.Pluralism, of course, has been the subject of repeated definition byBerlin and others (the repetition not always serving a clarifyingpurpose). However, the term ‘relativism’ often remainsunderanalysed in these discussions. Whether pluralism can bedistinguished from relativism depends largely on how relativism isdefined, as well as on how certain obscure or controversial componentsof pluralism are treated. It should also be noted that the question ofwhether values are plural is logically distinct from the question ofwhether they are objective, despite the frequent elision of the twotopics in the literature on this subject.

One way of defining relativism is as a form of subjectivism or moralirrationalism. This is how Berlin defined it in his attempts to refutethe charge of relativism brought against his pluralism. For Berlin,the model of a relativist statement is ‘I like my coffee white,you like yours black; that is simply the way it is; there is nothingto choose between us; I don’t understand how you can preferblack coffee, and you cannot understand how I can prefer white; wecannot agree.’ Applied to ethics, this same relativist attitudemight lead its holder to say: ‘I like human sacrifice, and youdo not; our tastes, and traditions, simply differ.’ Pluralism,on the other hand, as Berlin defines it, holds that understanding ofmoral views is possible among all people (unless they are so alienatedfrom normal human sentiments and beliefs as to be considered reallyderanged). Relativism, in Berlin’s definition, would make suchmoral understanding impossible; while pluralism explains thepossibility of (and acceptance of pluralism may facilitate) moralcommunication.

Another (related) way of differentiating pluralism and relativism,employed by Berlin and others, holds that pluralism accepts a basic‘core’ of human values, and that these and other valuesadopted alongside them in a particular context fall within a common‘human horizon’ (1990, 12). Though Berlin’s usage isnot entirely consistent, this horizon is best thought of as a boundaryenclosing any form of human conduct that is comprehensible to otherhuman beings in virtue of their shared humanity, whether or not theconduct is deemed acceptable. (Actions may be comprehensible butunacceptable for more than one reason, including mistaken empiricalbeliefs and – jointly or separately – what is known inreligious terminology as original sin, the innate human propensity tobehave immorally.) Beyond the horizon lies behaviour we cannot makesense of, and therefore regard as insane or irrational, such as theworship of wood simply because it is wood, or sticking pins into theflesh of living people just because it is pleasurable to pierceresilient surfaces, without regard to or even enjoyment of the painthis causes. The ‘core’ of shared or universal valuesaccounts for our agreement on at least some moral issues, for example,the immorality of ‘slavery or ritual murder or Nazi gaschambers’ (1990, 19). This view rests on a belief in a basic,minimum, universal human nature beneath the widely diverse forms thathuman life and belief have taken across time and place. It may alsoinvolve a belief in the existence of a specifically ‘moralsense’ inherent in human beings. Berlin seems to have believedin such a faculty (which he refers to under this name), and linked itto empathy, but did not develop this view in his writings.

Yet another way of defining relativism is to view it as holding thatthings have value onlyrelative to particular situations oroutlooks; nothing is intrinsically good – that is, valuable inand for itself. A slightly different way of putting this would be tomaintain that there are no such things as values that are alwaysvalid; values are valid to different degrees in differentcircumstances, but not others. For instance, liberty may be a leadingvalue in one place at one time, but has a much lower status as a valueat another. Here, again, Berlin’s pluralism seems opposed torelativism, since it is committed to the belief that, for humanbeings, at least some values are intrinsically rather thaninstrumentally good, and that at least some values are universallyvalid, even if others aren’t, and even if this universalvalidity isn’t recognised. Berlin admitted that liberty, forinstance, had historically been upheld as a pre-eminent ideal only bya minority of human beings; yet he still held it to be a genuine valuefor all human beings, everywhere, because of the way that human beingsare constituted, and, so far as we know, will continue to beconstituted. Similarly, Steven Lukes has suggested that relativismseeks to avoid or dismiss moral conflict, to explain it away byholding that different values hold for different people(‘Liberalism for the liberals, cannibalism for thecannibals’: Lukes 2001b; cf. Hollis 1999, 36), and by denyingthat the competing values may be, and often are, binding on allpeople. Pluralism, on the other hand, sees conflicts of values asoccurring both within, and across, cultures, and (at least inLukes’s formulation) maintains that custom or relatively validbelief-systems or ways of life cannot be appealed to as ways ofovercoming value-conflict (Lukes 1989). This is not a position thatBerlin explicitly advances; but his later writings suggest a sympathyfor it.

Berlin’s own position seems to lie somewhere between thisversion of relativism and Lukes’s proposal. He acknowledged thatcultures are not monolithic or morally ‘rational’ (thatis, conflicts of values are endemic within cultures), and denies thatcultural traditions or norms can be invoked to dissipate orauthoritatively resolve conflicts between values (as Michael Oakeshottsuggested when he appealed to the ‘intimations’ oftradition as a way of resolving apparent conflicts generated byattempts at ‘rational’ action: see Oakeshott 1962,125–34; Oakeshott 1965). But Berlin did hold that, as anempirical matter, most individuals do make decisions about how tobalance, reconcile, or choose between competing values in light oftheir existing general commitments and visions of life, which areshaped (though not completely determined) by cultural tradition andcontext. Liberty may be a genuine, and important, good for humanbeings in general; but how human beings decide to promote or actualiseliberty in relation to a whole web of other values will differ betweendifferent societies.

Yet the charge that pluralism is equivalent to relativism is not soeasily refuted, given certain ambiguities in Berlin’s account.These centre on the nature and origins of values, the related questionof the role of cultural norms, and the meaning of‘incommensurability’.

As stated above, Berlin held both that values are human creations, andthat they are ‘objective’. The foundation for this latterclaim is unclear in Berlin’s work. The claim that values areobjective in being founded on (or expressions of) and limited bycertain realities of human nature would seem to provide a defenceagainst relativism, in holding that there is an underlying, sharedhuman nature which makes at least some values non-relative. Theargument that values are objective simply because they are pursued byhuman beings may seem to allow for relativism, if it makes thevalidity of values dependent on nothing but human preferences, andallows any values actually pursued by human beings (and, therefore,any practices adopted in pursuing those values) to claim validity.[20] But this is areductio ad absurdum, to be deflected byadding two further considerations: how widespread aspirant universalvalues are; and whether they can be justified in terms of somerationally defensible conception of human welfare.

One of the knottiest dimensions of Berlin’s pluralism is theidea of incommensurability, which has led to diverginginterpretations. One can make a three-way distinction, between weakincommensurability, moderate incommensurability and radicalincommensurability. Weak incommensurability is the view that valuescannot be ranked quantitatively, but can be arranged in a qualitativehierarchy that applies consistently in all cases. Berlin goes furtherthan this, but it is not clear whether he presents a moderate or aradical version of incommensurability. The former holds that there isno single, ultimate scale or principle with which to measure values– no moral ‘slide-rule’ (2002b, 216) or universalunit of normative measurement. This view is certainly consistent withall that Berlin wrote from the 1930s onwards. Such a view does notnecessarily rule out making judgements between values on acase-by-case basis: just because values can’t be compared orranked in terms of one master-value or formula, we can’tconclude that it is impossible to compare or deliberate between themat all, as we indeed do in actual cases.

Berlin does sometimes offer more starkly dramatic accounts ofincommensurability, which make it hard to rule out the more radicalinterpretation of the concept, according to which incommensurabilityis more or less synonymous with incomparability. This interpretationstates that values cannot be compared at all, since there is no‘common currency’ in terms of which to compare them: eachvalue, beingsui generis, cannot be judged in relation to anyother value, because there is nothing in relation to which both can bejudged or measured. As a result, choices among values cannot be basedon (objectively valid) evaluative comparisons, but only on personalpreference, or on an act of radical, arbitrary choice, which Berlinsometimes calls ‘plumping’. But plumping need not be adisembodied, inexplicable act: it can draw, albeit subconsciously, ona hinterland of moral understanding rooted in the moral experience ofthe plumper and in his cultural tradition.

A related question concerns the role of reason in moral deliberation.If values are incommensurable, must all choices between conflictingvalues be ultimately subjective or irrational? If so, how doespluralism differ from radical relativism and subjectivism? If not,how, exactly, does moral reasoning work? How can we rationally makechoices between values when there is no system or unit of measurementthat can be used in making such deliberations? One possible answer tothe last question is to offer an account of practical, situationalreasoning that is not quantitative or rule-based, but appeals to themoral sense mentioned above. This is what Berlin suggests; but, onceagain, he does not offer a systematic explanation of the nature ofnon-systematic reason. (On incommensurability see Chang 1997 andCrowder 2002.)

In the area of political philosophy, the most widespread controversyover pluralism concerns its relationship to liberalism. This debateoverlaps with that regarding pluralism’s relationship torelativism, to the extent that liberalism is regarded as resting on abelief in certain universal values and fundamental human rights, abelief which relativism undermines. However, there are some whomaintain that, while pluralism is distinct from, and preferable to,relativism, it is nevertheless too radical, contested and subversiveto be be depended on for a justification of liberalism (or,conversely, that liberalism is too universalistic or absolutist to belinked to pluralism). The main proponent of this view, moreresponsible than any other thinker for the emergence and widediscussion of this issue, is John Gray (see, especially, Gray 1995).Gray asserts that pluralism is true, that pluralism underminesliberalism, and that therefore liberalism should be abandoned, atleast in its traditional role of a political philosophy claiminguniversal status.[21]

Gray’s case has spawned a vast literature, concerning bothBerlin’s own treatment of the relationship between pluralism andliberalism in particular, and this issue in general. Some theoristshave agreed with Gray (Kekes, 1993, 1997); others have sought to showthat pluralism and liberalism are reconcilable, although thisreconciliation may require modifications to both liberalism andpluralism – modifications that are, however, justifiable, andindeed inherently desirable. The most extensive discussions to dateare those by George Crowder and William Galston (Crowder 2002, 2004,2019, Galston 2002, 2004).[22]

Berlin himself was devoted both to pluralism and to liberalism, whichhe saw not as related by logical entailment (though he sometimes comesclose to positing this: e.g. 2002b, 216; Jahanbegloo 1992, 44), but asinterconnected and harmonious. The version of pluralism he advancedwas distinctly liberal in its assumptions, aims and conclusions, justas his liberalism was distinctly pluralist. As Michael Walzer hasremarked, Berlin’s pluralism is characterised by‘receptivity, generosity, and scepticism’, which are,‘if not liberal values, then qualities of mind that make it[…] likely that liberal values will be accepted’ (Galston2002, 60–1; Walzer 1995, 31).

5. Political Thought

5.1 The Concept of Liberty

Berlin’s best-known contribution to political theory is hisessay on the distinction between positive and negative liberty. Thisdistinction is explained, and the vast literature on it summarised,elsewhere in this encyclopedia; the following therefore focuses onlyon Berlin’s original argument, which has often beenmisunderstood, in part because of his own ambiguities. It should bestressed that the essay in question is principally concerned withpolitical liberty, not with what, late in life, he dubbed‘basic liberty’, which is freedom of choice (or freewill), without which any other kinds of liberty would be impossible:indeed, ‘which men cannot be without and remain men’ (A518; cf. UD 218, CTH2 309, and 2.4 above).

InTwo Concepts of Liberty Berlin sought to explain thedifference between two (out of more than two hundred, he said)different ways of thinking about political liberty. These, he said,had run through modern thought, and were central to the ideologicalstruggles of his day. Berlin called these two conceptions of libertynegative and positive.[23] Berlin’s treatment of these concepts was less than fullyeven-handed from the start: while he defined negative liberty fairlyclearly and simply, he gave positive liberty two different basicdefinitions, from which still more distinct conceptions would branchout. Negative liberty Berlin initially defined asfreedomfrom, that is, the absence of constraints on the agent imposed byother people. Positive liberty he defined both asfreedom to,that is, the ability (not just the opportunity) to pursue and achievewilled goals; and also as autonomy or self-rule, as opposed todependence on others. These are not the same.

Berlin’s account was further complicated by combining conceptualanalysis with history. He associated negative liberty with the liberaltradition as it had emerged and developed in Britain and France fromthe seventeenth century to the early nineteenth. He later regrettedthat he had not made more of the evils that negative liberty had beenused to justify, such as exploitation under laissez-faire capitalism;inTwo Concepts, however, negative liberty is portrayedfavourably, and briefly. It is on positive liberty that Berlinfocused, since it was, he claimed, both a more ambiguous concept, andone which had been subject to greater and more sinistertransformation, and ultimately perversion.

Berlin traced positive liberty back to theories that focus on theautonomy, or capacity for self-rule, of the agent.[24] Of these, he found Rousseau’s theory of liberty particularlydangerous. For, in Berlin’s account, Rousseau had equatedfreedom with self-rule, and self-rule with obedience to the so-called‘general will’. By this, Berlin alleged, Rousseau meant,essentially, the common or public interest – that is, what wasbest for all citizens qua citizens. The general will was quiteindependent of, and would often be at odds with, the particular willsof individuals, who, Rousseau charged, were often deluded as to theirown genuine interests.

This view clashed with Berlin’s political and moral outlook intwo ways. First, it posited the existence of a unique,‘true’ public interest, a single set of arrangements thatwas best for all citizens, and was thus opposed to the main thrust ofpluralism. Second, it rested on a bogus transformation of the conceptof the self. In his doctrine of the general will Rousseau moved fromthe conventional and, Berlin insisted, correct view of the self asindividual to the self as citizen – which for Rousseau meant theindividual as member of a larger community, an individual whoseidentity and well-being were exactly the same as those of the largercommunity. Rousseau transformed the concept of the self’s willfrom what the empirical individual actually desires to what theindividual as citizenought to desire, that is, what is inindividuals’ real best interest, whether they realise it ornot.

For Berlin, this transformation became more sinister still in thehands of Kant’s German disciples. Kant himself had identified‘positive’ freedom with autonomy, or self-determination,by the rational personality – the self freed from all thatrenders it ‘heteronymous’ and irrational. Later Germanphilosophers influenced by Kant went further in identifying the‘self’ whose self-determination constitutes freedom withentities other than the individual. Freedom becomes a matter ofovercoming the poor, flawed, false, empirical self – what oneappears to be and want – in order to realise one’s‘true’, ‘real’, ‘noumenal’ self.This ‘true’ self may be identified with one’s bestor true interests, either as an individual or as a member of a largergroup or institution. Thus Fichte (who began as a radicallyindividualist liberal, only to become, later, an ardent, evenhysterical, nationalist – an intellectual forefather of Fascismand even Nazism) came to equate freedom with the rule of the‘true’ self understood as the nation, orVolk. Onthis view, the individual achieves freedom only through renunciationof his or her desires and beliefs as an individual and submersion in alarger group. The ‘true’ self might also be identifiedwith a cause, an idea, or the dictates of rationality, as in the caseof Hegel’s definition of liberty, which equated it withrecognition of, and obedience to, the laws of history as revealed byreason. Such theoretical shifts set the stage, for Berlin, for theideologies of the totalitarian movements of the twentieth century,both Communist and Fascist–Nazi, which claimed to liberatepeople by subjecting – and often sacrificing – them tolarger groups or principles. To do this was the greatest of politicalevils; and to do it in the name of freedom, a political principle thatBerlin, as a genuine liberal, especially cherished, struck him as a‘strange […] reversal’ or ‘monstrousimpersonation’ (2002b, 198, 180). Against this, Berlinchampioned, as ‘truer and more humane’, negative libertyand an empirical view of the self.