Note

Go to the endto download the full example code.

Transformations Tutorial#

Like any graphics packages, Matplotlib is built on top of a transformationframework to easily move between coordinate systems, the userlanddatacoordinate system, theaxes coordinate system, thefigure coordinatesystem, and thedisplay coordinate system. In 95% of your plotting, youwon't need to think about this, as it happens under the hood, but as you pushthe limits of custom figure generation, it helps to have an understanding ofthese objects, so you can reuse the existing transformations Matplotlib makesavailable to you, or create your own (seematplotlib.transforms). Thetable below summarizes some useful coordinate systems, a description of eachsystem, and the transformation object for going from each coordinate system tothedisplay coordinates. In the "Transformation Object" column,ax is aAxes instance,fig is aFigure instance, andsubfigure is aSubFigure instance.

Coordinatesystem | Description | Transformation objectfrom system to display |

|---|---|---|

data | The coordinate system of the datain the Axes. |

|

axes | The coordinate system of the |

|

subfigure | The coordinate system of the |

|

figure | The coordinate system of the |

|

figure-inches | The coordinate system of the |

|

xaxis,yaxis | Blended coordinate systems, usingdata coordinates on one directionand axes coordinates on the other. |

|

display | The native coordinate system of theoutput ; (0, 0) is the bottom leftof the window, and (width, height)is top right of the output in"display units". "Display units" depends on thebackend. For example, Agg usespixels, and SVG/PDF use points. |

TheTransform objects are naive to the source anddestination coordinate systems, however the objects referred to in the tableabove are constructed to take inputs in their coordinate system, and transformthe input to thedisplay coordinate system. That is why thedisplaycoordinate system hasNone for the "Transformation Object" column -- italready is indisplay coordinates. The naming and destination conventionsare an aid to keeping track of the available "standard" coordinate systems andtransforms.

The transformations also know how to invert themselves (viaTransform.inverted) to generate a transform from output coordinate systemback to the input coordinate system. For example,ax.transData convertsvalues in data coordinates to display coordinates andax.transData.inverted() is amatplotlib.transforms.Transform thatgoes from display coordinates to data coordinates. This is particularly usefulwhen processing events from the user interface, which typically occur indisplay space, and you want to know where the mouse click or key-press occurredin yourdata coordinate system.

Note that specifying the position of Artists indisplay coordinates maychange their relative location if thedpi or size of the figure changes.This can cause confusion when printing or changing screen resolution, becausethe object can change location and size. Therefore, it is most common forartists placed in an Axes or figure to have their transform set to somethingother than theIdentityTransform(); the default when an artistis added to an Axes usingadd_artist is for the transform to beax.transData so that you can work and think indata coordinates and letMatplotlib take care of the transformation todisplay.

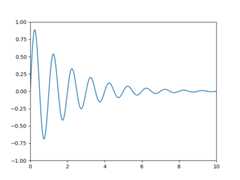

Data coordinates#

Let's start with the most commonly used coordinate, thedata coordinatesystem. Whenever you add data to the Axes, Matplotlib updates the datalimits,most commonly updated with theset_xlim() andset_ylim() methods. For example, in the figurebelow, the data limits stretch from 0 to 10 on the x-axis, and -1 to 1 on they-axis.

You can use theax.transData instance to transform from yourdata to yourdisplay coordinate system, either a single point or asequence of points as shown below:

In [14]:type(ax.transData)Out[14]:<class 'matplotlib.transforms.CompositeGenericTransform'>In [15]:ax.transData.transform((5,0))Out[15]:array([ 335.175, 247. ])In [16]:ax.transData.transform([(5,0),(1,2)])Out[16]:array([[ 335.175, 247. ], [ 132.435, 642.2 ]])

You can use theinverted()method to create a transform which will take you fromdisplay todatacoordinates:

In [41]:inv=ax.transData.inverted()In [42]:type(inv)Out[42]:<class 'matplotlib.transforms.CompositeGenericTransform'>In [43]:inv.transform((335.175,247.))Out[43]:array([ 5., 0.])

If your are typing along with this tutorial, the exact values of thedisplay coordinates may differ if you have a different window size ordpi setting. Likewise, in the figure below, the display labeledpoints are probably not the same as in the ipython session because thedocumentation figure size defaults are different.

x=np.arange(0,10,0.005)y=np.exp(-x/2.)*np.sin(2*np.pi*x)fig,ax=plt.subplots()ax.plot(x,y)ax.set_xlim(0,10)ax.set_ylim(-1,1)xdata,ydata=5,0# This computing the transform now, if anything# (figure size, dpi, axes placement, data limits, scales..)# changes re-calling transform will get a different value.xdisplay,ydisplay=ax.transData.transform((xdata,ydata))bbox=dict(boxstyle="round",fc="0.8")arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="->",connectionstyle="angle,angleA=0,angleB=90,rad=10")offset=72ax.annotate(f'data = ({xdata:.1f},{ydata:.1f})',(xdata,ydata),xytext=(-2*offset,offset),textcoords='offset points',bbox=bbox,arrowprops=arrowprops)disp=ax.annotate(f'display = ({xdisplay:.1f},{ydisplay:.1f})',(xdisplay,ydisplay),xytext=(0.5*offset,-offset),xycoords='figure pixels',textcoords='offset points',bbox=bbox,arrowprops=arrowprops)plt.show()

Warning

If you run the source code in the example above in a GUI backend,you may also find that the two arrows for thedata anddisplayannotations do not point to exactly the same point. This is becausethe display point was computed before the figure was displayed, andthe GUI backend may slightly resize the figure when it is created.The effect is more pronounced if you resize the figure yourself.This is one good reason why you rarely want to work indisplayspace, but you can connect to the'on_draw'Event to updatefigurecoordinates on figure draws; seeEvent handling and picking.

When you change the x or y limits of your axes, the data limits areupdated so the transformation yields a new display point. Note thatwhen we just change the ylim, only the y-display coordinate isaltered, and when we change the xlim too, both are altered. More onthis later when we talk about theBbox.

In [54]:ax.transData.transform((5,0))Out[54]:array([ 335.175, 247. ])In [55]:ax.set_ylim(-1,2)Out[55]:(-1, 2)In [56]:ax.transData.transform((5,0))Out[56]:array([ 335.175 , 181.13333333])In [57]:ax.set_xlim(10,20)Out[57]:(10, 20)In [58]:ax.transData.transform((5,0))Out[58]:array([-171.675 , 181.13333333])

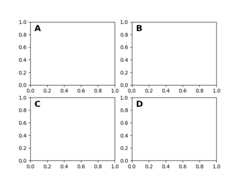

Axes coordinates#

After thedata coordinate system,axes is probably the second mostuseful coordinate system. Here the point (0, 0) is the bottom left ofyour Axes or subplot, (0.5, 0.5) is the center, and (1.0, 1.0) is the topright. You can also refer to points outside the range, so (-0.1, 1.1)is to the left and above your Axes. This coordinate system is extremelyuseful when placing text in your Axes, because you often want a text bubblein a fixed, location, e.g., the upper left of the Axes pane, and have thatlocation remain fixed when you pan or zoom. Here is a simple example thatcreates four panels and labels them 'A', 'B', 'C', 'D' as you often see injournals. A more sophisticated approach for such labeling is presented atLabelling subplots.

fig=plt.figure()fori,labelinenumerate(('A','B','C','D')):ax=fig.add_subplot(2,2,i+1)ax.text(0.05,0.95,label,transform=ax.transAxes,fontsize=16,fontweight='bold',va='top')plt.show()

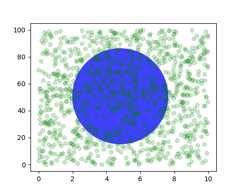

You can also make lines or patches in theaxes coordinate system, butthis is less useful in my experience than usingax.transAxes forplacing text. Nonetheless, here is a silly example which plots somerandom dots in data space, and overlays a semi-transparentCircle centered in the middle of the Axeswith a radius one quarter of the Axes -- if your Axes does notpreserve aspect ratio (seeset_aspect()),this will look like an ellipse. Use the pan/zoom tool to move around,or manually change the data xlim and ylim, and you will see the datamove, but the circle will remain fixed because it is not indatacoordinates and will always remain at the center of the Axes.

fig,ax=plt.subplots()x,y=10*np.random.rand(2,1000)ax.plot(x,y,'go',alpha=0.2)# plot some data in data coordinatescirc=mpatches.Circle((0.5,0.5),0.25,transform=ax.transAxes,facecolor='blue',alpha=0.75)ax.add_patch(circ)plt.show()

Blended transformations#

Drawing inblended coordinate spaces which mixaxes withdatacoordinates is extremely useful, for example to create a horizontalspan which highlights some region of the y-data but spans across thex-axis regardless of the data limits, pan or zoom level, etc. In factthese blended lines and spans are so useful, we have built-infunctions to make them easy to plot (seeaxhline(),axvline(),axhspan(),axvspan()) but for didactic purposes wewill implement the horizontal span here using a blendedtransformation. This trick only works for separable transformations,like you see in normal Cartesian coordinate systems, but not oninseparable transformations like thePolarTransform.

importmatplotlib.transformsastransformsfig,ax=plt.subplots()x=np.random.randn(1000)ax.hist(x,30)ax.set_title(r'$\sigma=1 \/ \dots \/ \sigma=2$',fontsize=16)# the x coords of this transformation are data, and the y coord are axestrans=transforms.blended_transform_factory(ax.transData,ax.transAxes)# highlight the 1..2 stddev region with a span.# We want x to be in data coordinates and y to span from 0..1 in axes coords.rect=mpatches.Rectangle((1,0),width=1,height=1,transform=trans,color='yellow',alpha=0.5)ax.add_patch(rect)plt.show()

Note

The blended transformations where x is indata coords and y inaxescoordinates is so useful that we have helper methods to return theversions Matplotlib uses internally for drawing ticks, ticklabels, etc.The methods arematplotlib.axes.Axes.get_xaxis_transform() andmatplotlib.axes.Axes.get_yaxis_transform(). So in the exampleabove, the call toblended_transform_factory() can bereplaced byget_xaxis_transform:

Plotting in physical coordinates#

Sometimes we want an object to be a certain physical size on the plot.Here we draw the same circle as above, but in physical coordinates. If doneinteractively, you can see that changing the size of the figure doesnot change the offset of the circle from the lower-left corner,does not change its size, and the circle remains a circle regardless ofthe aspect ratio of the Axes.

fig,ax=plt.subplots(figsize=(5,4))x,y=10*np.random.rand(2,1000)ax.plot(x,y*10.,'go',alpha=0.2)# plot some data in data coordinates# add a circle in fixed-coordinatescirc=mpatches.Circle((2.5,2),1.0,transform=fig.dpi_scale_trans,facecolor='blue',alpha=0.75)ax.add_patch(circ)plt.show()

If we change the figure size, the circle does not change its absoluteposition and is cropped.

fig,ax=plt.subplots(figsize=(7,2))x,y=10*np.random.rand(2,1000)ax.plot(x,y*10.,'go',alpha=0.2)# plot some data in data coordinates# add a circle in fixed-coordinatescirc=mpatches.Circle((2.5,2),1.0,transform=fig.dpi_scale_trans,facecolor='blue',alpha=0.75)ax.add_patch(circ)plt.show()

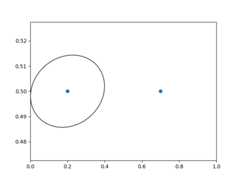

Another use is putting a patch with a set physical dimension around adata point on the Axes. Here we add together two transforms. Thefirst sets the scaling of how large the ellipse should be and the secondsets its position. The ellipse is then placed at the origin, and thenwe use the helper transformScaledTranslationto move itto the right place in theax.transData coordinate system.This helper is instantiated with:

trans=ScaledTranslation(xt,yt,scale_trans)

wherext andyt are the translation offsets, andscale_trans isa transformation which scalesxt andyt at transformation timebefore applying the offsets.

Note the use of the plus operator on the transforms below.This code says: first apply the scale transformationfig.dpi_scale_transto make the ellipse the proper size, but still centered at (0, 0),and then translate the data toxdata[0] andydata[0] in data space.

In interactive use, the ellipse stays the same size even if theaxes limits are changed via zoom.

fig,ax=plt.subplots()xdata,ydata=(0.2,0.7),(0.5,0.5)ax.plot(xdata,ydata,"o")ax.set_xlim(0,1)trans=(fig.dpi_scale_trans+transforms.ScaledTranslation(xdata[0],ydata[0],ax.transData))# plot an ellipse around the point that is 150 x 130 points in diameter...circle=mpatches.Ellipse((0,0),150/72,130/72,angle=40,fill=None,transform=trans)ax.add_patch(circle)plt.show()

Note

The order of transformation matters. Here the ellipseis given the right dimensions in display spacefirst and then movedin data space to the correct spot.If we had done theScaledTranslation first, thenxdata[0] andydata[0] wouldfirst be transformed todisplay coordinates ([358.4 475.2] ona 200-dpi monitor) and then those coordinateswould be scaled byfig.dpi_scale_trans pushing the center ofthe ellipse well off the screen (i.e.[71680. 95040.]).

Using offset transforms to create a shadow effect#

Another use ofScaledTranslation is to createa new transformation that isoffset from another transformation, e.g., to place one object shifted abit relative to another object. Typically, you want the shift to be insome physical dimension, like points or inches rather than indatacoordinates, so that the shift effect is constant at different zoomlevels and dpi settings.

One use for an offset is to create a shadow effect, where you draw oneobject identical to the first just to the right of it, and just belowit, adjusting the zorder to make sure the shadow is drawn first andthen the object it is shadowing above it.

Here we apply the transforms in theopposite order to the use ofScaledTranslation above. The plot isfirst made in data coordinates (ax.transData) and then shifted bydx anddy points usingfig.dpi_scale_trans. (In typography,apoint is1/72 inches, and by specifying your offsets in points, your figurewill look the same regardless of the dpi resolution it is saved in.)

fig,ax=plt.subplots()# make a simple sine wavex=np.arange(0.,2.,0.01)y=np.sin(2*np.pi*x)line,=ax.plot(x,y,lw=3,color='blue')# shift the object over 2 points, and down 2 pointsdx,dy=2/72.,-2/72.offset=transforms.ScaledTranslation(dx,dy,fig.dpi_scale_trans)shadow_transform=ax.transData+offset# now plot the same data with our offset transform;# use the zorder to make sure we are below the lineax.plot(x,y,lw=3,color='gray',transform=shadow_transform,zorder=0.5*line.get_zorder())ax.set_title('creating a shadow effect with an offset transform')plt.show()

Note

The dpi and inches offset is acommon-enough use case that we have a special helper function tocreate it inmatplotlib.transforms.offset_copy(), which returnsa new transform with an added offset. So above we could have done:

shadow_transform=transforms.offset_copy(ax.transData,fig,dx,dy,units='inches')

The transformation pipeline#

Theax.transData transform we have been working with in thistutorial is a composite of three different transformations thatcomprise the transformation pipeline fromdata ->displaycoordinates. Michael Droettboom implemented the transformationsframework, taking care to provide a clean API that segregated thenonlinear projections and scales that happen in polar and logarithmicplots, from the linear affine transformations that happen when you panand zoom. There is an efficiency here, because you can pan and zoomin your Axes which affects the affine transformation, but you may notneed to compute the potentially expensive nonlinear scales orprojections on simple navigation events. It is also possible tomultiply affine transformation matrices together, and then apply themto coordinates in one step. This is not true of all possibletransformations.

Here is how theax.transData instance is defined in the basicseparable axisAxes class:

self.transData=self.transScale+(self.transLimits+self.transAxes)

We've been introduced to thetransAxes instance above inAxes coordinates, which maps the (0, 0), (1, 1) corners of theAxes or subplot bounding box todisplay space, so let's look atthese other two pieces.

self.transLimits is the transformation that takes you fromdata toaxes coordinates; i.e., it maps your view xlim and ylimto the unit space of the Axes (andtransAxes then takes that unitspace to display space). We can see this in action here

In [80]:ax=plt.subplot()In [81]:ax.set_xlim(0,10)Out[81]:(0, 10)In [82]:ax.set_ylim(-1,1)Out[82]:(-1, 1)In [84]:ax.transLimits.transform((0,-1))Out[84]:array([ 0., 0.])In [85]:ax.transLimits.transform((10,-1))Out[85]:array([ 1., 0.])In [86]:ax.transLimits.transform((10,1))Out[86]:array([ 1., 1.])In [87]:ax.transLimits.transform((5,0))Out[87]:array([ 0.5, 0.5])

and we can use this same inverted transformation to go from the unitaxes coordinates back todata coordinates.

In [90]:inv.transform((0.25,0.25))Out[90]:array([ 2.5, -0.5])

The final piece is theself.transScale attribute, which isresponsible for the optional non-linear scaling of the data, e.g., forlogarithmic axes. When an Axes is initially setup, this is just set tothe identity transform, since the basic Matplotlib axes has linearscale, but when you call a logarithmic scaling function likesemilogx() or explicitly set the scale tologarithmic withset_xscale(), then theax.transScale attribute is set to handle the nonlinear projection.The scales transforms are properties of the respectivexaxis andyaxisAxis instances. For example, whenyou callax.set_xscale('log'), the xaxis updates its scale to amatplotlib.scale.LogScale instance.

For non-separable axes the PolarAxes, there is one more piece toconsider, the projection transformation. ThetransDatamatplotlib.projections.polar.PolarAxes is similar to that forthe typical separable matplotlib Axes, with one additional piecetransProjection:

self.transData=(self.transScale+self.transShift+self.transProjection+(self.transProjectionAffine+self.transWedge+self.transAxes))

transProjection handles the projection from the space,e.g., latitude and longitude for map data, or radius and theta for polardata, to a separable Cartesian coordinate system. There are severalprojection examples in thematplotlib.projections package, and thebest way to learn more is to open the source for those packages andsee how to make your own, since Matplotlib supports extensible axesand projections. Michael Droettboom has provided a nice tutorialexample of creating a Hammer projection axes; seeCustom projection.

Total running time of the script: (0 minutes 3.650 seconds)