Non-Euclidean geometry

In about300 BCEuclid wroteThe Elements, a book which was to become one of the most famous books ever written. Euclid stated five postulates on which he based all his theorems:

Proclus(410-485) wrote a commentary onThe Elements where he comments on attempted proofs to deduce the fifth postulate from the other four, in particular he notes thatPtolemy had produced a false 'proof'.Proclus then goes on to give a false proof of his own. However he did give the following postulate which is equivalent to the fifth postulate.

Many attempts were made to prove the fifth postulate from the other four, many of them being accepted as proofs for long periods of time until the mistake was found. Invariably the mistake was assuming some 'obvious' property which turned out to be equivalent to the fifth postulate. One such 'proof' was given byWallis in1663 when he thought he had deduced the fifth postulate, but he had actually shown it to be equivalent to:-

In this figureSaccheri proved that the summit angles at and were equal.The proof uses properties of congruent triangles whichEuclid proved in Propositions4 and8 which are proved before the fifth postulate is used.Saccheri has shown:

Euclid's fifth postulate is c).Saccheri proved that the hypothesis of the obtuse angle implied the fifth postulate, so obtaining a contradiction.Saccheri then studied the hypothesis of the acute angle and derived many theorems of non-Euclidean geometry without realising what he was doing. However he eventually 'proved' that the hypothesis of the acute angle led to a contradiction by assuming that there is a 'point at infinity' which lies on a plane.

In1766Lambert followed a similar line toSaccheri. However he did not fall into the trap thatSaccheri fell into and investigated the hypothesis of the acute angle without obtaining a contradiction.Lambert noticed that, in this new geometry, the angle sum of a triangle increased as the area of the triangle decreased.

Legendre spent40 years of his life working on the parallel postulate and the work appears in appendices to various editions of his highly successful geometry bookEléments de GéométrieⓉ.Legendre proved thatEuclid's fifth postulate is equivalent to:-

Elementary geometry was by this time engulfed in the problems of the parallel postulate.D'Alembert, in1767, called itthe scandal of elementary geometry.

The first person to really come to understand the problem of the parallels wasGauss. He began work on the fifth postulate in1792 while only15 years old, at first attempting to prove the parallels postulate from the other four. By1813 he had made little progress and wrote:

Gauss discussed the theory of parallels with his friend, the mathematicianFarkas Bolyai who made several false proofs of the parallel postulate.Farkas Bolyai taught his son,János Bolyai, mathematics but, despite advising his sonnot to waste one hour's time on that problem of the problem of the fifth postulate,János Bolyai did work on the problem.

In1823János Bolyai wrote to his father sayingI have discovered things so wonderful that I was astounded ... out of nothing I have created a strange new world. However it tookBolyai a further two years before it was all written down and he published hisstrange new world as a24 page appendix to his father's book, although just to confuse future generations the appendix was published before the book itself.

Gauss, after reading the24 pages, describedJános Bolyai in these words while writing to a friend:I regard this young geometer Bolyai as a genius of the first order . However in some senseBolyai only assumed that the new geometry was possible. He then followed the consequences in a not too dissimilar fashion from those who had chosen to assume the fifth postulate was false and seek a contradiction. However the real breakthrough was the belief that the new geometry was possible.Gauss, however impressed he sounded in the above quote withBolyai, rather devastatedBolyai by telling him that he(Gauss) had discovered all this earlier but had not published. Although this must undoubtedly have been true, it detracts in no way fromBolyai's incredible breakthrough.

Nor isBolyai's work diminished becauseLobachevsky published a work on non-Euclidean geometry in1829. NeitherBolyai norGauss knew ofLobachevsky's work, mainly because it was only published in Russian in theKazan Messenger a local university publication.Lobachevsky's attempt to reach a wider audience had failed when his paper was rejected byOstrogradski.

In factLobachevsky fared no better thanBolyai in gaining public recognition for his momentous work. He publishedGeometrical investigations on the theory of parallels in1840 which, in its61 pages, gives the clearest account ofLobachevsky's work. The publication of an account in French inCrelle's Journal in1837 brought his work on non-Euclidean geometry to a wide audience but the mathematical community was not ready to accept ideas so revolutionary.

InLobachevsky's1840 booklet he explains clearly how his non-Euclidean geometry works.

HenceLobachevsky has replaced the fifth postulate ofEuclid by:-

Riemann, who wrote his doctoral dissertation underGauss's supervision, gave an inaugural lecture on10 June1854 in which he reformulated the whole concept of geometry which he saw as a space with enough extra structure to be able to measure things like length. This lecture was not published until1868, two years afterRiemann's death but was to have a profound influence on the development of a wealth of different geometries.Riemann briefly discussed a 'spherical' geometry in which every line through a point not on a line meets the line. In this geometry no parallels are possible.

It is important to realise that neitherBolyai's norLobachevsky's description of their new geometry had been proved to be consistent. In fact it was no different from Euclidean geometry in this respect although the many centuries of work with Euclidean geometry was sufficient to convince mathematicians that no contradiction would ever appear within it.

The first person to put theBolyai -Lobachevsky non-Euclidean geometry on the same footing as Euclidean geometry wasEugenio Beltrami(1835-1900). In1868 he wrote a paperEssay on the interpretation of non-Euclidean geometry which produced a model for2-dimensional non-Euclidean geometry within3-dimensional Euclidean geometry. The model was obtained on the surface of revolution of a tractrix about its asymptote. This is sometimes called apseudo-sphere.

You can see the graph of a tractrix atTHIS LINK and what the top half of a Pseudo-sphere looks like atTHIS LINK.

In factBeltrami's model was incomplete but it certainly gave a final decision on the fifth postulate ofEuclid since the model provided a setting in whichEuclid's first four postulates held but the fifth did not hold. It reduced the problem of consistency of the axioms of non-Euclidean geometry to that of the consistency of the axioms of Euclidean geometry.

Beltrami's work on a model ofBolyai -Lobachevsky's non-Euclidean geometry was completed byKlein in1871.Klein went further than this and gave models of other non-Euclidean geometries such asRiemann's spherical geometry.Klein's work was based on a notion of distance defined byCayley in1859 when he proposed a generalised definition for distance.

Klein showed that there are three basically different types of geometry. In theBolyai -Lobachevsky type of geometry, straight lines have two infinitely distant points. In theRiemann type of spherical geometry, lines have no(or more precisely two imaginary) infinitely distant points. Euclidean geometry is a limiting case between the two where for each line there are two coincident infinitely distant points.

- To draw a straight line from any point to any other.

- To produce a finite straight line continuously in a straight line.

- To describe a circle with any centre and distance.

- That all right angles are equal to each other.

- That, if a straight line falling on two straight lines make the interior angles on the same side less than two right angles, if produced indefinitely, meet on that side on which are the angles less than the two right angles.

Proclus(410-485) wrote a commentary onThe Elements where he comments on attempted proofs to deduce the fifth postulate from the other four, in particular he notes thatPtolemy had produced a false 'proof'.Proclus then goes on to give a false proof of his own. However he did give the following postulate which is equivalent to the fifth postulate.

Playfair's Axiom:- Given a line and a point not on the line, it is possible to draw exactly one line through the given point parallel to the line.Although known from the time ofProclus, this became known asPlayfair's Axiom afterJohn Playfair wrote a famous commentary onEuclid in1795 in which he proposed replacingEuclid's fifth postulate by this axiom.

Many attempts were made to prove the fifth postulate from the other four, many of them being accepted as proofs for long periods of time until the mistake was found. Invariably the mistake was assuming some 'obvious' property which turned out to be equivalent to the fifth postulate. One such 'proof' was given byWallis in1663 when he thought he had deduced the fifth postulate, but he had actually shown it to be equivalent to:-

To each triangle, there exists a similar triangle of arbitrary magnitude.One of the attempted proofs turned out to be more important than most others. It was produced in1697 byGirolamo Saccheri. The importance ofSaccheri's work was that he assumed the fifth postulate false and attempted to derive a contradiction.

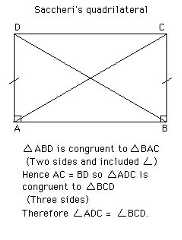

Here is theSaccheri quadrilateral

In this figureSaccheri proved that the summit angles at and were equal.The proof uses properties of congruent triangles whichEuclid proved in Propositions4 and8 which are proved before the fifth postulate is used.Saccheri has shown:

a) The summit angles are >90°(hypothesis of the obtuse angle).

b) The summit angles are <90°(hypothesis of the acute angle).

c) The summit angles are =90°(hypothesis of the right angle).

Euclid's fifth postulate is c).Saccheri proved that the hypothesis of the obtuse angle implied the fifth postulate, so obtaining a contradiction.Saccheri then studied the hypothesis of the acute angle and derived many theorems of non-Euclidean geometry without realising what he was doing. However he eventually 'proved' that the hypothesis of the acute angle led to a contradiction by assuming that there is a 'point at infinity' which lies on a plane.

In1766Lambert followed a similar line toSaccheri. However he did not fall into the trap thatSaccheri fell into and investigated the hypothesis of the acute angle without obtaining a contradiction.Lambert noticed that, in this new geometry, the angle sum of a triangle increased as the area of the triangle decreased.

Legendre spent40 years of his life working on the parallel postulate and the work appears in appendices to various editions of his highly successful geometry bookEléments de GéométrieⓉ.Legendre proved thatEuclid's fifth postulate is equivalent to:-

The sum of the angles of a triangle is equal to two right angles.Legendre showed, asSaccheri had over100 years earlier, that the sum of the angles of a triangle cannot be greater than two right angles. This, again likeSaccheri, rested on the fact that straight lines were infinite. In trying to show that the angle sum cannot be less than180°Legendre assumed that through any point in the interior of an angle it is always possible to draw a line which meets both sides of the angle. This turns out to be another equivalent form of the fifth postulate, butLegendre never realised his error himself.

Elementary geometry was by this time engulfed in the problems of the parallel postulate.D'Alembert, in1767, called itthe scandal of elementary geometry.

The first person to really come to understand the problem of the parallels wasGauss. He began work on the fifth postulate in1792 while only15 years old, at first attempting to prove the parallels postulate from the other four. By1813 he had made little progress and wrote:

In the theory of parallels we are even now not further thanEuclid. This is a shameful part of mathematics...However by1817Gauss had become convinced that the fifth postulate was independent of the other four postulates. He began to work out the consequences of a geometry in which more than one line can be drawn through a given point parallel to a given line. Perhaps most surprisingly of allGauss never published this work but kept it a secret. At this time thinking was dominated by Kant who had stated that Euclidean geometry isthe inevitable necessity of thought andGauss disliked controversy.

Gauss discussed the theory of parallels with his friend, the mathematicianFarkas Bolyai who made several false proofs of the parallel postulate.Farkas Bolyai taught his son,János Bolyai, mathematics but, despite advising his sonnot to waste one hour's time on that problem of the problem of the fifth postulate,János Bolyai did work on the problem.

In1823János Bolyai wrote to his father sayingI have discovered things so wonderful that I was astounded ... out of nothing I have created a strange new world. However it tookBolyai a further two years before it was all written down and he published hisstrange new world as a24 page appendix to his father's book, although just to confuse future generations the appendix was published before the book itself.

Gauss, after reading the24 pages, describedJános Bolyai in these words while writing to a friend:I regard this young geometer Bolyai as a genius of the first order . However in some senseBolyai only assumed that the new geometry was possible. He then followed the consequences in a not too dissimilar fashion from those who had chosen to assume the fifth postulate was false and seek a contradiction. However the real breakthrough was the belief that the new geometry was possible.Gauss, however impressed he sounded in the above quote withBolyai, rather devastatedBolyai by telling him that he(Gauss) had discovered all this earlier but had not published. Although this must undoubtedly have been true, it detracts in no way fromBolyai's incredible breakthrough.

Nor isBolyai's work diminished becauseLobachevsky published a work on non-Euclidean geometry in1829. NeitherBolyai norGauss knew ofLobachevsky's work, mainly because it was only published in Russian in theKazan Messenger a local university publication.Lobachevsky's attempt to reach a wider audience had failed when his paper was rejected byOstrogradski.

In factLobachevsky fared no better thanBolyai in gaining public recognition for his momentous work. He publishedGeometrical investigations on the theory of parallels in1840 which, in its61 pages, gives the clearest account ofLobachevsky's work. The publication of an account in French inCrelle's Journal in1837 brought his work on non-Euclidean geometry to a wide audience but the mathematical community was not ready to accept ideas so revolutionary.

InLobachevsky's1840 booklet he explains clearly how his non-Euclidean geometry works.

All straight lines which in a plane go out from a point can, with reference to a given straight line in the same plane, be divided into two classes - into cutting and non-cutting. The boundary lines of the one and the other class of those lines will be called parallel to the given line.

Here is theLobachevsky's diagram

HenceLobachevsky has replaced the fifth postulate ofEuclid by:-

Lobachevsky's Parallel Postulate. There exist two lines parallel to a given line through a given point not on the line.Lobachevsky went on to develop many trigonometric identities for triangles which held in this geometry, showing that as the triangle became small the identities tended to the usual trigonometric identities.

Riemann, who wrote his doctoral dissertation underGauss's supervision, gave an inaugural lecture on10 June1854 in which he reformulated the whole concept of geometry which he saw as a space with enough extra structure to be able to measure things like length. This lecture was not published until1868, two years afterRiemann's death but was to have a profound influence on the development of a wealth of different geometries.Riemann briefly discussed a 'spherical' geometry in which every line through a point not on a line meets the line. In this geometry no parallels are possible.

It is important to realise that neitherBolyai's norLobachevsky's description of their new geometry had been proved to be consistent. In fact it was no different from Euclidean geometry in this respect although the many centuries of work with Euclidean geometry was sufficient to convince mathematicians that no contradiction would ever appear within it.

The first person to put theBolyai -Lobachevsky non-Euclidean geometry on the same footing as Euclidean geometry wasEugenio Beltrami(1835-1900). In1868 he wrote a paperEssay on the interpretation of non-Euclidean geometry which produced a model for2-dimensional non-Euclidean geometry within3-dimensional Euclidean geometry. The model was obtained on the surface of revolution of a tractrix about its asymptote. This is sometimes called apseudo-sphere.

You can see the graph of a tractrix atTHIS LINK and what the top half of a Pseudo-sphere looks like atTHIS LINK.

In factBeltrami's model was incomplete but it certainly gave a final decision on the fifth postulate ofEuclid since the model provided a setting in whichEuclid's first four postulates held but the fifth did not hold. It reduced the problem of consistency of the axioms of non-Euclidean geometry to that of the consistency of the axioms of Euclidean geometry.

Beltrami's work on a model ofBolyai -Lobachevsky's non-Euclidean geometry was completed byKlein in1871.Klein went further than this and gave models of other non-Euclidean geometries such asRiemann's spherical geometry.Klein's work was based on a notion of distance defined byCayley in1859 when he proposed a generalised definition for distance.

Klein showed that there are three basically different types of geometry. In theBolyai -Lobachevsky type of geometry, straight lines have two infinitely distant points. In theRiemann type of spherical geometry, lines have no(or more precisely two imaginary) infinitely distant points. Euclidean geometry is a limiting case between the two where for each line there are two coincident infinitely distant points.

References(show)

- R Bonola,Non-Euclidean Geometry : A Critical and Historical Study of its Development(New York,1955).

- T R Chandrasekhar, Non-Euclidean geometry from early times to Beltrami,Indian J. Hist. Sci.24(4)(1989),249-256.

- N Daniels,Thomas Reid's discovery of a non-Euclidean geometry,Philos. Sci.39(1972),219-234.

- F J Duarte, On the non-Euclidean geometries : Historical and bibliographical notes(Spanish),Revista Acad. Colombiana Ci. Exact. Fis. Nat.7(1946),63-81.

- H Freudenthal, Nichteuklidische Geometrie im Altertum?,Archive for History of Exact Sciences43(3)(1991),189-197.

- J J Gray, Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometry, in I Grattan-Guinness(ed.),Companion Encyclopedia of the History and Philosophy of the Mathematical Sciences(London,1994),877-886.

- J J Gray,Ideas of Space : Euclidean, non-Euclidean and Relativistic(Oxford,1989).

- J J Gray, Non-Euclidean geometry-a re-interpretation,Historia Mathematica6(3)(1979),236-258.

- J J Gray, The discovery of non-Euclidean geometry, inStudies in the history of mathematics(Washington, DC,1987),37-60.

- T Hawkins, Non-Euclidean geometry and Weierstrassian mathematics : the background to Killing's work on Lie algebras,Historia Mathematica7(3)(1980),289-342.

- C Houzel,The birth of non-Euclidean geometry, in1830-1930 : a century of geometry(Berlin,1992),3-21.

- V F Kagan, The construction of non-Euclidean geometry by Lobachevskii, Gauss and Bolyai(Russian),Akad. Nauk SSSR. Trudy Inst. Istorii Estestvoznaniya2(1948),323-389.

- H Karzel, Development of non-Euclidean geometries since Gauss,Proceedings of the2nd Gauss Symposium(Berlin,1995).

- B Mayorga, Lobachevskii and non-Euclidean geometry(Spanish),Lect. Mat.15(1)(1994),29-43.

- T Pati, The development of non-Euclidean geometry during the last150 years,Bull. Allahabad Univ. Math. Assoc.15(1951),1-8.

- B A Rosenfeld,A history of non-euclidean geometry : evolution of the concept of a geometric space(New York,1987).

- B A Rozenfel'd,History of non-Euclidean geometry : Development of the concept of a geometric space(Russian)(Moscow,1976).

- D M Y Sommerville,Bibliography of non-euclidean geometry(New York,1970).

- B Szénássy, Remarks on Gauss's work on non-Euclidean geometry(Hungarian),Mat. Lapok28(1-3)(1980),133-140.

- R Taton, Lobatchevski et la diffusion des géometries non-euclidiennes,The Spanish scientist before the history of science(Madrid,1980),39-46.

- I Toth, From the pre-history of non-euclidean geometry(Hungarian),Mat. Lapok16(1965),300-315.

- R J Trudeau,The non-Euclidean revolution(Boston, Mass.,1987).

- A Vucinich, Nikolai Ivanovich Lobachevskii : the man behind the first non-Euclidean geometry,Isis53(1962),465-481.

Additional Resources(show)

Other pages about Non-Euclidean geometry:

Written byJ J O'Connor and E F Robertson

Last Update February 1996

Last Update February 1996

MacTutor

MacTutor