1 Exploratory Data Analysis

Listening to the numbers :)

1.1 Profiling, The voice of the numbers

“The voice of the numbers” – a metaphor byEduardo Galeano. Writer and novelist.

The data we explore could be like Egyptian hieroglyphs without a correct interpretation. Profiling is the very first step in a series of iterative stages in the pursuit of finding what the data want to tell us, if we are patient enough to listen.

This chapter will cover, with a few functions, a complete data profiling. This should be the entry step in a data project, where we start by knowing the correct data types and exploring distributions in numerical and categorical variables.

It also focuses on the extraction of semantic conclusions, which is useful when writing a report for non-technical people.

What are we going to review in this chapter?

- Dataset health status:

- Getting metrics like total rows, columns, data types, zeros, and missing values

- How each of the previous items impacts on different analysis

- How to quickly filter and operate on (and with) them, to clean the data

- Univariate analysis in categorical variable:

- Frequency, percentage, cumulative value, and colorful plots

- Univariate analysis with numerical variables:

- Percentile, dispersion, standard deviation, mean, top and bottom values

- Percentile vs. quantile vs. quartile

- Kurtosis, skewness, inter-quartile range, variation coefficient

- Plotting distributions

- Completecase study based on“Data World”, data preparation, and data analysis

Functions summary review in the chapter:

df_status(data): Profiling dataset structuredescribe(data): Numerical and categorical profiling (quantitative)freq(data): Categorical profiling (quantitative and plot).profiling_num(data): Profiling for numerical variables (quantitative)plot_num(data): Profiling for numerical variables (plots)

Note:describe is in theHmisc package while remaining functions are infunModeling.

1.1.1 Dataset health status

The quantity of zeros, NA, Inf, unique values as well as the data type may lead to a good or bad model. Here’s an approach to cover the very first step in data modeling.

First, we load thefunModeling anddplyr libraries.

# Loading funModeling!library(funModeling)library(dplyr)data(heart_disease)1.1.1.1 Checking missing values, zeros, data type, and unique values

Probably one of the first steps, when we get a new dataset to analyze, is to know if there are missing values (NA inR) and the data type.

Thedf_status function coming infunModeling can help us by showing these numbers in relative and percentage values. It also retrieves the infinite and zeros statistics.

# Profiling the data inputdf_status(heart_disease)

Figure 1.1: Dataset health status

q_zeros: quantity of zeros (p_zeros: in percent)q_inf: quantity of infinite values (p_inf: in percent)q_na: quantity of NA (p_na: in percent)type: factor or numericunique: quantity of unique values

1.1.1.2 Why are these metrics important?

- Zeros: Variables withlots of zeros may not be useful for modeling and, in some cases, they may dramatically bias the model.

- NA: Several models automatically exclude rows with NA (random forest for example). As a result, the final model can be biased due to several missing rows because of only one variable. For example, if the data contains only one out of 100 variables with 90% of NAs, the model will be training with only 10% of the original rows.

- Inf: Infinite values may lead to an unexpected behavior in some functions in R.

- Type: Some variables are encoded as numbers, but they are codes or categories and the modelsdon’t handle them in the same way.

- Unique: Factor/categorical variables with a high number of different values (~30) tend to do overfitting if the categories have low cardinality (decision trees, for example).

1.1.1.3 Filtering unwanted cases

The functiondf_status takes a data frame and returns astatus table that can help us quickly remove features (or variables) based on all the metrics described in the last section. For example:

Removing variables with ahigh number of zeros

# Profiling the Data Inputmy_data_status=df_status(heart_disease,print_results = F)# Removing variables with 60% of zero valuesvars_to_remove=filter(my_data_status, p_zeros>60)%>%.$variablevars_to_remove## [1] "fasting_blood_sugar" "exer_angina" "exter_angina"# Keeping all columns except the ones present in 'vars_to_remove' vectorheart_disease_2=select(heart_disease,-one_of(vars_to_remove))Ordering data by percentage of zeros

arrange(my_data_status,-p_zeros)%>%select(variable, q_zeros, p_zeros)## variable q_zeros p_zeros## 1 fasting_blood_sugar 258 85.15## 2 exer_angina 204 67.33## 3 exter_angina 204 67.33## 4 num_vessels_flour 176 58.09## 5 heart_disease_severity 164 54.13## 6 resting_electro 151 49.83## 7 oldpeak 99 32.67## 8 age 0 0.00## 9 gender 0 0.00## 10 chest_pain 0 0.00## 11 resting_blood_pressure 0 0.00## 12 serum_cholestoral 0 0.00## 13 max_heart_rate 0 0.00## 14 slope 0 0.00## 15 thal 0 0.00## 16 has_heart_disease 0 0.00The same reasoning applies when we want to remove (or keep) those variables above or below a certain threshold. Please check the missing values chapter to get more information about the implications when dealing with variables containing missing values.

1.1.1.4 Going deep into these topics

Values returned bydf_status are deeply covered in other chapters:

- Missing values (NA) treatment, analysis, and imputation are deeply covered in theMissing Data chapter.

- Data type, its conversions and implications when handling different data types and more are covered in theData Types chapter.

- A high number ofunique values is synonymous for high-cardinality variables. This situation is studied in both chapters:

1.1.1.5 Getting other common statistics:total rows,total columns andcolumn names:

# Total rowsnrow(heart_disease)## [1] 303# Total columnsncol(heart_disease)## [1] 16# Column namescolnames(heart_disease)## [1] "age" "gender" ## [3] "chest_pain" "resting_blood_pressure"## [5] "serum_cholestoral" "fasting_blood_sugar" ## [7] "resting_electro" "max_heart_rate" ## [9] "exer_angina" "oldpeak" ## [11] "slope" "num_vessels_flour" ## [13] "thal" "heart_disease_severity"## [15] "exter_angina" "has_heart_disease"1.1.2 Profiling categorical variables

Make sure you have the latest ‘funModeling’ version (>= 1.6).

Frequency or distribution analysis is made simple by thefreq function. This retrieves the distribution in a table and a plot (by default) and shows the distribution of absolute and relative numbers.

If you want the distribution for two variables:

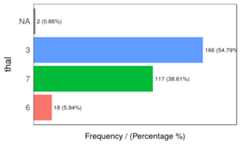

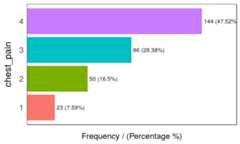

freq(data=heart_disease,input =c('thal','chest_pain'))

Figure 1.2: Frequency analysis 1

## thal frequency percentage cumulative_perc## 1 3 166 54.79 54.79## 2 7 117 38.61 93.40## 3 6 18 5.94 99.34## 4 <NA> 2 0.66 100.00

Figure 1.2: Frequency analysis 2

## chest_pain frequency percentage cumulative_perc## 1 4 144 47.52 47.52## 2 3 86 28.38 75.90## 3 2 50 16.50 92.40## 4 1 23 7.59 100.00## [1] "Variables processed: thal, chest_pain"As well as in the remainingfunModeling functions, ifinput is missing, then it will run for all factor or character variables present in a given data frame:

freq(data=heart_disease)If we only want to print the table excluding the plot, then we set theplot parameter toFALSE. Thefreq example can also handle asingle variable as an input. Bydefault,NA valuesare considered in both the table and the plot. If it is needed to exclude theNA then setna.rm = TRUE. Both examples in the following line:

freq(data=heart_disease$thal,plot =FALSE,na.rm =TRUE)If only one variable is provided, thenfreq returns the printed table; thus, it is easy to perform some calculations based on the variables it provides.

- For example, to print the categories that represent most of the 80% of the share (based on

cumulative_perc < 80). - To get the categories belonging to thelong tail, i.e., filtering by

percentage < 1by retrieving those categories appearing less than 1% of the time.

In addition, as with the other plot functions in the package, if there is a need to export plots, then add thepath_out parameter, which will create the folder if it’s not yet created.

freq(data=heart_disease,path_out='my_folder')1.1.2.0.1 Analysis

The output is ordered by thefrequency variable, which quickly analyzes the most frequent categories and how many shares they represent (cummulative_perc variable). In general terms, we as human beings like order. If the variables are not ordered, then our eyes start moving over all the bars to do the comparison and our brains place each bar in relation to the other bars.

Check the difference for the same data input, first without order and then with order:

Figure 1.3: Order and beauty

Generally, there are just a few categories that appear most of the time.

A more complete analysis is inHigh Cardinality Variable in Descriptive Stats

1.1.2.1 Introducing thedescribe function

This function comes in theHmisc package and allows us to quickly profile a complete dataset for both numerical and categorical variables. In this case, we’ll select only two variables and we will analyze the result.

# Just keeping two variables to use in this exampleheart_disease_3=select(heart_disease, thal, chest_pain)# Profiling the data!describe(heart_disease_3)## heart_disease_3 ## ## 2 Variables 303 Observations## ---------------------------------------------------------------------------## thal ## n missing distinct ## 301 2 3 ## ## Value 3 6 7## Frequency 166 18 117## Proportion 0.551 0.060 0.389## ---------------------------------------------------------------------------## chest_pain ## n missing distinct ## 303 0 4 ## ## Value 1 2 3 4## Frequency 23 50 86 144## Proportion 0.076 0.165 0.284 0.475## ---------------------------------------------------------------------------Where:

n: quantity of non-NArows. In this case, it indicates there are301patients containing a number.missing: number of missing values. Summing this indicator tongives us the total number of rows.unique: number of unique (or distinct) values.

The other information is pretty similar to thefreq function and returns between parentheses the total number in relative and absolute values for each different category.

1.1.3 Profiling numerical variables

This section is separated into two parts:

- Part 1: Introducing the “World Data” case study

- Part 2: Doing the numerical profiling in R

If you don’t want to know how the data preparation stage from Data World is calculated, then you can jump to “Part 2: Doing the numerical profiling in R”, when the profiling started.

1.1.3.1 Part 1: Introducing the World Data case study

This contains many indicators regarding world development. Regardless the profiling example, the idea is to provide a ready-to-use table for sociologists, researchers, etc. interested in analyzing this kind of data.

The original data source is:http://databank.worldbank.org. There you will find a data dictionary that explains all the variables.

First, we have to do some data wrangling. We are going to keep with the newest value per indicator.

library(Hmisc)# Loading data from the book repository without altering the formatdata_world=read.csv(file ="https://goo.gl/2TrDgN",header = T,stringsAsFactors = F,na.strings ="..")# Excluding missing values in Series.Code. The data downloaded from the web page contains four lines with "free-text" at the bottom of the file.data_world=filter(data_world, Series.Code!="")# The magical function that keeps the newest values for each metric. If you're not familiar with R, then skip it.max_ix<-function(d) { ix=which(!is.na(d)) res=ifelse(length(ix)==0,NA, d[max(ix)])return(res)}data_world$newest_value=apply(data_world[,5:ncol(data_world)],1,FUN=max_ix)# Printing the first three rowshead(data_world,3)## Series.Name Series.Code## 1 Population living in slums (% of urban population) EN.POP.SLUM.UR.ZS## 2 Population living in slums (% of urban population) EN.POP.SLUM.UR.ZS## 3 Population living in slums (% of urban population) EN.POP.SLUM.UR.ZS## Country.Name Country.Code X1990..YR1990. X2000..YR2000. X2007..YR2007.## 1 Afghanistan AFG NA NA NA## 2 Albania ALB NA NA NA## 3 Algeria DZA 11.8 NA NA## X2008..YR2008. X2009..YR2009. X2010..YR2010. X2011..YR2011.## 1 NA NA NA NA## 2 NA NA NA NA## 3 NA NA NA NA## X2012..YR2012. X2013..YR2013. X2014..YR2014. X2015..YR2015.## 1 NA NA 62.7 NA## 2 NA NA NA NA## 3 NA NA NA NA## X2016..YR2016. newest_value## 1 NA 62.7## 2 NA NA## 3 NA 11.8The columnsSeries.Name andSeries.Code are the indicators to be analyzed.Country.Name andCountry.Code are the countries. Each row represents a unique combination of country and indicator. Remaining columns,X1990..YR1990. (year 1990),X2000..YR2000. (year 2000),X2007..YR2007. (year 2007), and so on indicate the metric value for that year, thus each column is a year.

1.1.3.2 Making a data scientist decision

There are manyNAs because some countries don’t have the measure of the indicator in those years. At this point, we need tomake a decision as a data scientist. Probably no the optimal if we don’t ask to an expert, e.g., a sociologist.

What to do with theNA values? In this case, we are going to to keep with thenewest value for all the indicators. Perhaps this is not the best way to extract conclusions for a paper as we are going to compare some countries with information up to 2016 while other countries will be updated only to 2009. To compare all the indicators with the newest data is a valid approach for the first analysis.

Another solution could have been to keep with the newest value, but only if this number belongs to the last five years. This would reduce the number of countries to analyze.

These questions are impossible to answer for anartificial intelligence system, yet the decision can change the results dramatically.

The last transformation

The next step will convert the last table fromlong towide format. In other words, each row will represent a country and each column an indicator (thanks to the last transformation that has thenewest value for each combination of indicator-country).

The indicator names are unclear, so we will “translate” a few of them.

# Get the list of indicator descriptions.names=unique(select(data_world, Series.Name, Series.Code))head(names,5)## Series.Name Series.Code## 1 Population living in slums (% of urban population) EN.POP.SLUM.UR.ZS## 218 Income share held by second 20% SI.DST.02ND.20## 435 Income share held by third 20% SI.DST.03RD.20## 652 Income share held by fourth 20% SI.DST.04TH.20## 869 Income share held by highest 20% SI.DST.05TH.20# Convert a fewdf_conv_world=data.frame(new_name=c("urban_poverty_headcount","rural_poverty_headcount","gini_index","pop_living_slums","poverty_headcount_1.9"),Series.Code=c("SI.POV.URHC","SI.POV.RUHC","SI.POV.GINI","EN.POP.SLUM.UR.ZS","SI.POV.DDAY"),stringsAsFactors = F)# adding the new indicator valuedata_world_2 =left_join(data_world, df_conv_world,by="Series.Code",all.x=T)data_world_2 =mutate(data_world_2,Series.Code_2=ifelse(!is.na(new_name),as.character(data_world_2$new_name), data_world_2$Series.Code) )Any indicator meaning can be checked in data.worldbank.org. For example, if we want to know whatEN.POP.SLUM.UR.ZS means, then we type:http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.POP.SLUM.UR.ZS

# The package 'reshape2' contains both 'dcast' and 'melt' functionslibrary(reshape2)data_world_wide=dcast(data_world_2, Country.Name~Series.Code_2,value.var ="newest_value")Note: To understand more aboutlong andwide format usingreshape2 package, and how to convert from one to another, please go tohttp://seananderson.ca/2013/10/19/reshape.html.

Now we have the final table to analyze:

# Printing the first three rowshead(data_world_wide,3)## Country.Name gini_index pop_living_slums poverty_headcount_1.9## 1 Afghanistan NA 62.7 NA## 2 Albania 28.96 NA 1.06## 3 Algeria NA 11.8 NA## rural_poverty_headcount SI.DST.02ND.20 SI.DST.03RD.20 SI.DST.04TH.20## 1 38.3 NA NA NA## 2 15.3 13.17 17.34 22.81## 3 4.8 NA NA NA## SI.DST.05TH.20 SI.DST.10TH.10 SI.DST.FRST.10 SI.DST.FRST.20 SI.POV.2DAY## 1 NA NA NA NA NA## 2 37.82 22.93 3.66 8.85 6.79## 3 NA NA NA NA NA## SI.POV.GAP2 SI.POV.GAPS SI.POV.NAGP SI.POV.NAHC SI.POV.RUGP SI.POV.URGP## 1 NA NA 8.4 35.8 9.3 5.6## 2 1.43 0.22 2.9 14.3 3.0 2.9## 3 NA NA NA 5.5 0.8 1.1## SI.SPR.PC40 SI.SPR.PC40.ZG SI.SPR.PCAP SI.SPR.PCAP.ZG## 1 NA NA NA NA## 2 4.08 -1.2205 7.41 -1.3143## 3 NA NA NA NA## urban_poverty_headcount## 1 27.6## 2 13.6## 3 5.81.1.3.3 Part 2: Doing the numerical profiling in R

We will see the following functions:

describefromHmiscprofiling_num(full univariate analysis), andplot_num(hisotgrams) fromfunModeling

We’ll pick up only two variables as an example:

library(Hmisc)# contains the `describe` functionvars_to_profile=c("gini_index","poverty_headcount_1.9")data_subset=select(data_world_wide,one_of(vars_to_profile))# Using the `describe` on a complete dataset. # It can be run with one variable; for example, describe(data_subset$poverty_headcount_1.9)describe(data_subset)## data_subset ## ## 2 Variables 217 Observations## ---------------------------------------------------------------------------## gini_index ## n missing distinct Info Mean Gmd .05 .10 ## 140 77 136 1 38.8 9.594 26.81 27.58 ## .25 .50 .75 .90 .95 ## 32.35 37.69 43.92 50.47 53.53 ## ## lowest : 24.09 25.59 25.90 26.12 26.13, highest: 56.24 60.46 60.79 60.97 63.38## ---------------------------------------------------------------------------## poverty_headcount_1.9 ## n missing distinct Info Mean Gmd .05 .10 ## 116 101 107 1 18.33 23.56 0.025 0.075 ## .25 .50 .75 .90 .95 ## 1.052 6.000 33.815 54.045 67.328 ## ## lowest : 0.00 0.01 0.03 0.04 0.06, highest: 68.64 68.74 70.91 77.08 77.84## ---------------------------------------------------------------------------Takingpoverty_headcount_1.9 (Poverty headcount ratio at $1.90 a day is the percentage of the population living on less than $1.90 a day at 2011 international prices.), we can describe it as:

n: quantity of non-NArows. In this case, it indicates116countries that contain a number.missing: number of missing values. Summing this indicator tongives us the total number of rows. Almost half of the countries have no data.unique: number of unique (or distinct) values.Info: an estimator of the amount of information present in the variable and not important at this point.Mean: the classical mean or average.- Numbers:

.05,.10,.25,.50,.75,.90and.95stand for the percentiles. These values are really useful since it helps us to describe the distribution. It will be deeply covered later on, i.e.,.05is the 5th percentile. lowestandhighest: the five lowest/highest values. Here, we can spot outliers and data errors. For example, if the variable represents a percentage, then it cannot contain negative values.

The next function isprofiling_num which takes a data frame and retrieves abig table, easy to get overwhelmed in asea of metrics. This is similar to what we can see in the movieThe Matrix.

Figure 1.4: The matrix of data

Picture from the movie: “The Matrix” (1999). The Wachowski Brothers (Directors).

The idea of the following table is to give to the user afull set of metrics,, for then, she or he can decide which ones to pick for the study.

Note: Every metric has a lot of statistical theory behind it. Here we’ll be covering just a tiny andoversimplified approach to introduce the concepts.

library(funModeling)# Full numerical profiling in one function automatically excludes non-numerical variablesprofiling_num(data_world_wide)## variable mean std_dev variation_coef p_01 p_05## 1 gini_index 38.8 8.49 0.22 25.711 26.815## 2 pop_living_slums 45.7 23.66 0.52 6.830 10.750## 3 poverty_headcount_1.9 18.3 22.74 1.24 0.000 0.025## 4 rural_poverty_headcount 41.2 21.91 0.53 2.902 6.465## 5 SI.DST.02ND.20 10.9 2.17 0.20 5.568 7.361## 6 SI.DST.03RD.20 15.2 2.03 0.13 9.137 11.828## 7 SI.DST.04TH.20 21.5 1.49 0.07 16.286 18.288## 8 SI.DST.05TH.20 45.9 7.14 0.16 35.004 36.360## 9 SI.DST.10TH.10 30.5 6.75 0.22 20.729 21.988## 10 SI.DST.FRST.10 2.5 0.87 0.34 0.916 1.147## 11 SI.DST.FRST.20 6.5 1.87 0.29 2.614 3.369## 12 SI.POV.2DAY 32.4 30.64 0.95 0.061 0.393## 13 SI.POV.GAP2 14.2 16.40 1.16 0.012 0.085## 14 SI.POV.GAPS 6.9 10.10 1.46 0.000 0.000## 15 SI.POV.NAGP 12.2 10.12 0.83 0.421 1.225## 16 SI.POV.NAHC 30.7 17.88 0.58 1.842 6.430## 17 SI.POV.RUGP 15.9 11.83 0.75 0.740 1.650## 18 SI.POV.URGP 8.3 8.24 0.99 0.300 0.900## 19 SI.SPR.PC40 10.3 9.75 0.95 0.857 1.228## 20 SI.SPR.PC40.ZG 2.0 3.62 1.85 -6.232 -3.021## 21 SI.SPR.PCAP 21.1 17.44 0.83 2.426 3.138## 22 SI.SPR.PCAP.ZG 1.5 3.21 2.20 -5.897 -3.805## 23 urban_poverty_headcount 23.3 15.06 0.65 0.579 3.140## p_25 p_50 p_75 p_95 p_99 skewness kurtosis iqr range_98## 1 32.348 37.7 43.9 53.5 60.9 0.552 2.9 11.6 [25.71, 60.9]## 2 25.175 46.2 65.6 83.4 93.4 0.087 2.0 40.5 [6.83, 93.41]## 3 1.052 6.0 33.8 67.3 76.2 1.125 2.9 32.8 [0, 76.15]## 4 25.250 38.1 57.6 75.8 81.7 0.051 2.0 32.3 [2.9, 81.7]## 5 9.527 11.1 12.6 14.2 14.6 -0.411 2.7 3.1 [5.57, 14.57]## 6 13.877 15.5 16.7 17.9 18.1 -0.876 3.8 2.8 [9.14, 18.14]## 7 20.758 21.9 22.5 23.0 23.4 -1.537 5.6 1.8 [16.29, 23.39]## 8 40.495 44.8 49.8 58.1 65.9 0.738 3.3 9.3 [35, 65.89]## 9 25.710 29.5 34.1 42.2 50.6 0.905 3.6 8.4 [20.73, 50.62]## 10 1.885 2.5 3.2 3.9 4.3 0.043 2.2 1.4 [0.92, 4.35]## 11 5.092 6.5 8.0 9.4 10.0 -0.119 2.2 2.9 [2.61, 10]## 12 3.828 20.3 63.2 84.6 90.3 0.536 1.8 59.4 [0.06, 90.34]## 13 1.305 5.5 26.3 48.5 56.2 1.063 2.9 25.0 [0.01, 56.18]## 14 0.287 1.4 10.3 31.5 38.3 1.654 4.7 10.0 [0, 38.29]## 15 4.500 8.7 16.9 32.4 36.7 1.129 4.0 12.4 [0.42, 36.72]## 16 16.350 26.6 44.2 63.0 71.6 0.529 2.4 27.9 [1.84, 71.64]## 17 5.950 13.6 22.5 37.7 45.3 0.801 3.0 16.5 [0.74, 45.29]## 18 2.900 6.3 9.9 25.1 35.2 2.316 9.8 7.0 [0.3, 35.17]## 19 3.475 6.9 12.7 28.9 35.4 1.251 3.4 9.2 [0.86, 35.35]## 20 -0.084 1.7 4.6 7.9 9.0 -0.294 3.3 4.7 [-6.23, 9]## 21 8.003 15.3 25.4 52.8 67.2 1.132 3.3 17.4 [2.43, 67.17]## 22 -0.486 1.3 3.6 7.0 8.5 -0.018 3.6 4.0 [-5.9, 8.48]## 23 12.708 20.1 31.2 51.0 61.8 0.730 3.0 18.5 [0.58, 61.75]## range_80## 1 [27.58, 50.47]## 2 [12.5, 75.2]## 3 [0.08, 54.05]## 4 [13.99, 71.99]## 5 [8.28, 13.8]## 6 [12.67, 17.5]## 7 [19.73, 22.81]## 8 [36.99, 55.24]## 9 [22.57, 39.89]## 10 [1.48, 3.67]## 11 [3.99, 8.89]## 12 [0.79, 78.29]## 13 [0.16, 40.85]## 14 [0.02, 23.45]## 15 [1.85, 27]## 16 [9.86, 58.22]## 17 [3.3, 32.2]## 18 [1.3, 19.1]## 19 [1.81, 27.63]## 20 [-2.64, 6.48]## 21 [4.25, 49.22]## 22 [-2.07, 5.17]## 23 [5.98, 46.11]Each indicator hasits raison d’être:

variable: variable namemean: the well-known mean or averagestd_dev: standard deviation, a measure ofdispersion orspread around the mean value. A value around0means almost no variation (thus, it seems more like a constant); on the other side, it is harder to set whathigh is, but we can tell that the higher the variation the greater the spread.Chaos may look like infinite standard variation. The unit is the same as the mean so that it can be compared.variation_coef: variation coefficient=std_dev/mean. Because thestd_devis an absolute number, it’s good to have an indicator that puts it in a relative number, comparing thestd_devagainst themeanA value of0.22indicates thestd_devis 22% of themeanIf it were close to0then the variable tends to be more centered around the mean. If we compare two classifiers, then we may prefer the one with lessstd_devandvariation_coefon its accuracy.p_01,p_05,p_25,p_50,p_75,p_95,p_99:Percentiles at 1%, 5%, 25%, and so on. Later on in this chapter is a complete review about percentiles.

For a full explanation about percentiles, please go to:Annex 1: The magic of percentiles.

skewness: is a measure ofasymmetry. Close to0 indicates that the distribution isequally distributed (or symmetrical) around its mean. Apositive number implies a long tail on the right, whereas anegative number means the opposite. After this section, check the skewness in the plots. The variablepop_living_slumsis close to 0 (“equally” distributed),poverty_headcount_1.9is positive (tail on the right), andSI.DST.04TH.20is negative (tail on the left). The further the skewness is from 0 the more likely the distribution is to haveoutlierskurtosis: describes the distributiontails; keeping it simple, a higher number may indicate the presence of outliers (just as we’ll see later for the variableSI.POV.URGPholding an outlier around the value50For a complete skewness and kurtosis review, check Refs.(McNeese2016) and(Handbook2013).iqr: the inter-quartile range is the result of looking at percentiles0.25and0.75and indicates, in the same variable unit, the dispersion length of 50% of the values. The higher the value the more sparse the variable.range_98andrange_80: indicates the range where98%of the values are. It removes the bottom and top 1% (thus, the98%number). It is good to know the variable range without potential outliers. For example,pop_living_slumsgoes from0to76.15It’smore robust than comparing themin andmax values. Therange_80is the same as therange_98but without the bottom and top10%

iqr,range_98 andrange_80 are based on percentiles, which we’ll be covering later in this chapter.

Important: All the metrics are calculated having removed theNA values. Otherwise, the table would be filled with NA`s.

1.1.3.3.1 Advice when usingprofiling_num

The idea ofprofiling_num is to provide to the data scientist with a full set of metrics, so they can select the most relevant. This can easily be done using theselect function from thedplyr package.

In addition, we have to set inprofiling_num the parameterprint_results = FALSE. This way we avoid the printing in the console.

For example, let’s get with themean,p_01,p_99 andrange_80:

my_profiling_table=profiling_num(data_world_wide,print_results =FALSE)%>%select(variable, mean, p_01, p_99, range_80)# Printing only the first three rowshead(my_profiling_table,3)## variable mean p_01 p_99 range_80## 1 gini_index 39 25.7 61 [27.58, 50.47]## 2 pop_living_slums 46 6.8 93 [12.5, 75.2]## 3 poverty_headcount_1.9 18 0.0 76 [0.08, 54.05]Please note thatprofiling_num returns a table, so we can quickly filter cases given on the conditions we set.

1.1.3.3.2 Profiling numerical variables by plotting

Another function infunModeling isplot_num which takes a dataset and plots the distribution of every numerical variable while automatically excluding the non-numerical ones:

plot_num(data_world_wide)

Figure 1.5: Profiling numerical data

We can adjust the number of bars used in the plot by changing thebins parameter (default value is set to 10). For example:plot_num(data_world_wide, bins = 20).

1.1.4 Final thoughts

Many numbers have appeared here so far,and even more in the percentile appendix. The important point is for you to find the right approach to explore your data. This can come from other metrics or other criteria.

The functionsdf_status,describe,freq,profiling_num andplot_num can be run at the beginning of a data project.

Regarding thenormal and abnormal behavior on data, it’s important to study both. To describe the dataset in general terms, we should exclude the extreme values: for example, withrange_98 variable. The mean should decrease after the exclusion.

These analyses areunivariate; that is, they do not take into account other variables (multivariate analysis). This will be part of this book later on. Meanwhile, for the correlation between input (and output) variables, you can check theCorrelation chapter.

1.2 Correlation and Relationship

Manderbolt fractal, where the chaos expresses its beauty; image source: Wikipedia.

1.2.1 What is this about?

This chapter contains both methodological and practical aspects of measuring correlation in variables. We will see thatcorrelation word can be translated into “functional relationship”.

In methodological you will find the Anscombe Quartet, a set of four plots with dissimilar spatial distribution, but sharing the same correlation measure. We’ll go one step ahead re-calculating their relationship though a more robust metric (MIC).

We will mentionInformation Theory several times, although by now it’s not going to be covered at the mathematical level, it’s planned to. Many algorithms are based on it, even deep learning.

Understanding these concepts in low dimension (two variables) and small data (a bunch of rows) allow us to better understand high dimensional data. Nonetheless, some real cases are onlysmall data.

From the practical point of view, you’ll be able to replicate the analysis with your own data, profiling and exposing their relationships in fancy plots.

Let’s starting loading all needed libraries.

# Loading needed librarieslibrary(funModeling)# contains heart_disease datalibrary(minerva)# contains MIC statisticlibrary(ggplot2)library(dplyr)library(reshape2)library(gridExtra)# allow us to plot two plots in a rowoptions(scipen=999)# disable scientific notation1.2.2 Linear correlation

Perhaps the most standard correlation measure for numeric variables is theR statistic (or Pearson coefficient) which goes from1positive correlation to-1negative correlation. A value around0 implies no correlation.

Consider the following example, which calculates R measure based on a target variable (for example to do feature engineering). Functioncorrelation_table retrieves R metric for all numeric variables skipping the categorical/nominal ones.

correlation_table(data=heart_disease,target="has_heart_disease")## Variable has_heart_disease## 1 has_heart_disease 1.00## 2 heart_disease_severity 0.83## 3 num_vessels_flour 0.46## 4 oldpeak 0.42## 5 slope 0.34## 6 age 0.23## 7 resting_blood_pressure 0.15## 8 serum_cholestoral 0.08## 9 max_heart_rate -0.42Variableheart_disease_severity is the most important -numerical- variable, the higher its value the higher the chances of having a heart disease (positive correlation). Just the opposite tomax_heart_rate, which has a negative correlation.

Squaring this number returns theR-squared statistic (akaR2), which goes from0no correlation to1high correlation.

R statistic is highly influenced byoutliers andnon-linear relationships.

1.2.2.1 Correlation on Anscombe’s Quartet

Take a look at theAnscombe’s quartet, quotingWikipedia:

They were constructed in 1973 by the statistician Francis Anscombe to demonstrate both the importance of graphing data before analyzing it and the effect of outliers on statistical properties.

1973 and still valid, fantastic.

These four relationships are different, but all of them have the same R2:0.816.

Following example calculates the R2 and plot every pair.

# Reading anscombe quartet dataanscombe_data =read.delim(file="https://goo.gl/mVLz5L",header = T)# calculating the correlation (R squared, or R2) for#every pair, every value is the same: 0.86.cor_1 =cor(anscombe_data$x1, anscombe_data$y1)cor_2 =cor(anscombe_data$x2, anscombe_data$y2)cor_3 =cor(anscombe_data$x3, anscombe_data$y3)cor_4 =cor(anscombe_data$x4, anscombe_data$y4)# defining the functionplot_anscombe <-function(x, y, value, type){# 'anscombe_data' is a global variable, this is# a bad programming practice ;) p=ggplot(anscombe_data,aes_string(x,y))+geom_smooth(method='lm',fill=NA)+geom_point(aes(colour=factor(1),fill =factor(1)),shape=21,size =2 )+ylim(2,13)+xlim(4,19)+theme_minimal()+theme(legend.position="none")+annotate("text",x =12,y =4.5,label =sprintf("%s: %s", type,round(value,2) ) )return(p)}# plotting in a 2x2 gridgrid.arrange(plot_anscombe("x1","y1", cor_1,"R2"),plot_anscombe("x2","y2", cor_2,"R2"),plot_anscombe("x3","y3", cor_3,"R2"),plot_anscombe("x4","y4", cor_4,"R2"),ncol=2,nrow=2)

Figure 1.6: Anscombe set

4-different plots, having the samemean for everyx andy variable (9 and 7.501 respectively), and the same degree of correlation. You can check all the measures by typingsummary(anscombe_data).

This is why is so important to plot relationships when analyzing correlations.

We’ll back on this data later. It can be improved! First, we’ll introduce some concepts of information theory.

1.2.3 Correlation based on Information Theory

This relationships can be measure better withInformation Theory concepts. One of the many algorithms to measure correlation based on this is:MINE, acronym for: Maximal Information-based nonparametric exploration.

The implementation in R can be found inminerva package. It’s also available in other languages like Python.

1.2.3.1 An example in R: A perfect relationship

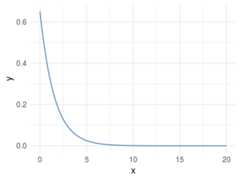

Let’s plot a non-linear relationship, directly based on a function (negative exponential), and print the MIC value.

x=seq(0,20,length.out=500)df_exp=data.frame(x=x,y=dexp(x,rate=0.65))ggplot(df_exp,aes(x=x,y=y))+geom_line(color='steelblue')+theme_minimal()

Figure 1.7: A perfect relationship

# position [1,2] contains the correlation of both variables, excluding the correlation measure of each variable against itself.# Calculating linear correlationres_cor_R2=cor(df_exp)[1,2]^2sprintf("R2: %s",round(res_cor_R2,2))## [1] "R2: 0.39"# now computing the MIC metricres_mine=mine(df_exp)sprintf("MIC: %s", res_mine$MIC[1,2])## [1] "MIC: 1"MIC value goes from 0 to 1. Being 0 implies no correlation and 1 highest correlation. The interpretation is the same as the R-squared.

1.2.3.2 Results analysis

TheMIC=1 indicates there is a perfect correlation between the two variables. If we were doingfeature engineering this variable should be included.

Further than a simple correlation, what the MIC says is: “Hey these two variables show a functional relationship”.

In machine learning terms (and oversimplifying): “variabley is dependant of variablex and a function -that we don’t know which one- can be found model the relationship.”

This is tricky because that relationship was effectively created based on a function, an exponential one.

But let’s continue with other examples…

1.2.4 Adding noise

Noise is an undesired signal adding to the original one. In machine learning noise helps the model to get confused. Concretely: two identical input cases -for example customers- have different outcomes -one buy and the other doesn’t-.

Now we are going to add some noise creating they_noise_1 variable.

df_exp$y_noise_1=jitter(df_exp$y,factor =1000,amount =NULL)ggplot(df_exp,aes(x=x,y=y_noise_1))+geom_line(color='steelblue')+theme_minimal()

Figure 1.8: Adding some noise

Calculating the correlation and MIC again, printing in both cases the entire matrix, which shows the correlation/MIC metric of each input variable against all the others including themselves.

# calculating R squaredres_R2=cor(df_exp)^2res_R2## x y y_noise_1## x 1.00 0.39 0.39## y 0.39 1.00 0.99## y_noise_1 0.39 0.99 1.00# Calculating mineres_mine_2=mine(df_exp)# Printing MICres_mine_2$MIC## x y y_noise_1## x 1.00 1.00 0.74## y 1.00 1.00 0.74## y_noise_1 0.74 0.74 1.00Adding noise to the data decreases the MIC value from 1 to 0.7226365 (-27%), and this is great!

R2 also decreased but just a little bit, from 0.3899148 to 0.3866319 (-0.8%).

Conclusion: MIC reflects a noisy relationship much better than R2, and it’s helpful to find correlated associations.

About the last example: Generate data based on a function is only for teaching purposes. But the concept of noise in variables is quite common inalmostevery data set, no matter its source. You don’t have to do anything to add noise to variables, it’s already there. Machine learning models deal with this noise, by approaching to thereal shape of data.

It’s quite useful to use the MIC measure to get a sense of the information present in a relationship between two variables.

1.2.5 Measuring non-linearity (MIC-R2)

mine function returns several metrics, we checked onlyMIC, but due to the nature of the algorithm (you can check the original paper(Reshef et al.2011)), it computes more interesting indicators. Check them all by inspectingres_mine_2 object.

One of them isMICR2, used as a measure ofnon-linearity. It is calculated by doing the: MIC - R2. Since R2 measures the linearity, a highMICR2 would indicate a non-linear relationship.

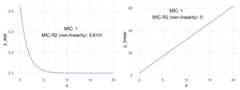

We can check it by calculating the MICR2 manually, following two matrix returns the same result:

# MIC r2: non-linearity metricround(res_mine_2$MICR2,3)# calculating MIC r2 manuallyround(res_mine_2$MIC-res_R2,3)Non-linear relationships are harder to build a model, even more using a linear algorithm like decision trees or linear regression.

Imagine we need to explain the relationship to another person, we’ll need “more words” to do it. It’s easier to say:“A increases as B increases and the ratio is always 3x” (if A=1 then B=3, linear).

In comparison to:“A increases as B increases, but A is almost 0 until B reaches the value 10, then A raises to 300; and when B reaches 15, A goes to 1000.”

# creating data exampledf_example=data.frame(x=df_exp$x,y_exp=df_exp$y,y_linear=3*df_exp$x+2)# getting mine metricsres_mine_3=mine(df_example)# generating labels to print the resultsresults_linear =sprintf("MIC: %s\n MIC-R2 (non-linearity): %s", res_mine_3$MIC[1,3],round(res_mine_3$MICR2[1,3],2) )results_exp =sprintf("MIC: %s\n MIC-R2 (non-linearity): %s", res_mine_3$MIC[1,2],round(res_mine_3$MICR2[1,2],4) )# Plotting results# Creating plot exponential variablep_exp=ggplot(df_example,aes(x=x,y=y_exp))+geom_line(color='steelblue')+annotate("text",x =11,y =0.4,label = results_exp)+theme_minimal()# Creating plot linear variablep_linear=ggplot(df_example,aes(x=x,y=y_linear))+geom_line(color='steelblue')+annotate("text",x =8,y =55,label = results_linear)+theme_minimal()grid.arrange(p_exp,p_linear,ncol=2)

Figure 1.9: Comparing relationships

Both plots show a perfect correlation (or relationship), holding an MIC=1. Regarding non-linearity, MICR2 behaves as expected, iny_exp=0.6101, and iny_linear=0.

This point is important since theMIC behaves like R2 does in linear relationships, plus it adapts quite well tonon-linear relationships as we saw before, retrieving a particular score metric (MICR2) to profile the relationship.

1.2.6 Measuring information on Anscombe Quartet

Remember the example we review at the beginning? Every pair of Anscombe Quartet returns aR2 of 0.86. But based on its plots it was clearly that not every pair exhibits neither a good correlation nor a similar distribution ofx andy.

But what happen if we measure the relationship with a metric based on Information Theory? Yes, MIC again.

# calculating the MIC for every pairmic_1=mine(anscombe_data$x1, anscombe_data$y1,alpha=0.8)$MICmic_2=mine(anscombe_data$x2, anscombe_data$y2,alpha=0.8)$MICmic_3=mine(anscombe_data$x3, anscombe_data$y3,alpha=0.8)$MICmic_4=mine(anscombe_data$x4, anscombe_data$y4,alpha=0.8)$MIC# plotting MIC in a 2x2 gridgrid.arrange(plot_anscombe("x1","y1", mic_1,"MIC"),plot_anscombe("x2","y2", mic_2,"MIC"),plot_anscombe("x3","y3", mic_3,"MIC"),plot_anscombe("x4","y4", mic_4,"MIC"),ncol=2,nrow=2)

Figure 1.10: MIC statistic

As you may notice we increased thealpha value to 0.8, this is a good practice -according to the documentation- when we analyzed small samples. The default value is 0.6 and its maximum 1.

In this case, MIC value spotted the most spurious relationship in the pairx4 - y4. Probably due to a few cases per plot (11 rows) the MIC was the same for all the others pairs. Having more cases will show different MIC values.

But when combining the MIC withMIC-R2 (non-linearity measurement) new insights appears:

# Calculating the MIC for every pair, note the "MIC-R2" object has the hyphen when the input are two vectors, unlike when it takes a data frame which is "MICR2".mic_r2_1=mine(anscombe_data$x1, anscombe_data$y1,alpha =0.8)$`MIC-R2`mic_r2_2=mine(anscombe_data$x2, anscombe_data$y2,alpha =0.8)$`MIC-R2`mic_r2_3=mine(anscombe_data$x3, anscombe_data$y3,alpha =0.8)$`MIC-R2`mic_r2_4=mine(anscombe_data$x4, anscombe_data$y4,alpha =0.8)$`MIC-R2`# Ordering according mic_r2df_mic_r2=data.frame(pair=c(1,2,3,4),mic_r2=c(mic_r2_1,mic_r2_2,mic_r2_3,mic_r2_4))%>%arrange(-mic_r2)df_mic_r2## pair mic_r2## 1 2 0.33## 2 3 0.33## 3 1 0.33## 4 4 -0.23Ordering decreasingly by itsnon-linearity the results are consisent with the plots: 2 > 3 > 1 > 4. Something strange for pair 4, a negative number. This is because MIC is lower than the R2. A relationship that worth to be plotted.

1.2.7 Measuring non-monotonicity: MAS measure

MINE can also help us to profile time series regarding its non-monotonicity withMAS (maximum asymmetry score).

A monotonic series is such it never changes its tendency, it always goes up or down. More on this on(Wikipedia2017b).

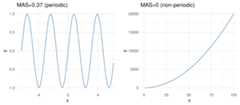

Following example simulates two-time series, one not-monotonicy_1 and the other monotonicy_2.

# creating sample data (simulating time series)time_x=sort(runif(n=1000,min=0,max=1))y_1=4*(time_x-0.5)^2y_2=4*(time_x-0.5)^3# Calculating MAS for both seriesmas_y1=round(mine(time_x,y_1)$MAS,2)mas_y2=mine(time_x,y_2)$MAS# Putting all togetherdf_mono=data.frame(time_x=time_x,y_1=y_1,y_2=y_2)# Plottinglabel_p_y_1 =sprintf("MAS=%s (goes down\n and up => not-monotonic)", mas_y1)p_y_1=ggplot(df_mono,aes(x=time_x,y=y_1))+geom_line(color='steelblue')+theme_minimal()+annotate("text",x =0.45,y =0.75,label = label_p_y_1)label_p_y_2=sprintf("MAS=%s (goes up => monotonic)", mas_y2)p_y_2=ggplot(df_mono,aes(x=time_x,y=y_2))+geom_line(color='steelblue')+theme_minimal()+annotate("text",x =0.43,y =0.35,label = label_p_y_2)grid.arrange(p_y_1,p_y_2,ncol=2)

Figure 1.11: Monotonicity in functions

From another perspective, MAS is also useful to detect periodic relationships. Let’s illustrate this with an example

Figure 1.12: Periodicity in functions

1.2.7.1 A more real example: Time Series

Consider the following case which contains three-time series:y1,y2 andy3. They can be profiled concerning its non-monotonicity or overall growth trend.

# reading datadf_time_series =read.delim(file="https://goo.gl/QDUjfd")# converting to long format so they can be plotteddf_time_series_long=melt(df_time_series,id="time")# Plottingplot_time_series =ggplot(data=df_time_series_long,aes(x=time,y=value,colour=variable))+geom_line()+theme_minimal()+scale_color_brewer(palette="Set2")plot_time_series

Figure 1.13: Time series example

# Calculating and printing MAS values for time series datamine_ts=mine(df_time_series)mine_ts$MAS## time y1 y2 y3## time 0.00 0.120 0.105 0.191## y1 0.12 0.000 0.068 0.081## y2 0.11 0.068 0.000 0.057## y3 0.19 0.081 0.057 0.000We need to look attime column, so we’ve got the MAS value of each series regarding the time.y2 is the most monotonic (and less periodic) series, and it can be confirmed by looking at it. It seems to be always up.

MAS summary:

- MAS ~ 0 indicates monotonic or non-periodic function (“always” up or down)

- MAS ~ 1 indicates non-monotonic or periodic function

1.2.8 Correlation between time series

MIC metric can also measure thecorrelation in time series, it is not a general purpose tool but can be helpful to compare different series quickly.

This section is based on the same data we used in MAS example.

# printing again the 3-time seriesplot_time_series

Figure 1.14: Time series example

# Printing MIC valuesmine_ts$MIC## time y1 y2 y3## time 1.00 0.38 0.69 0.34## y1 0.38 1.00 0.62 0.71## y2 0.69 0.62 1.00 0.52## y3 0.34 0.71 0.52 1.00Now we need to look aty1 column. According to MIC measure, we can confirm the same that it’s shown in last plot:

y1 is more similar toy3 (MIC=0.709) than what isy2 (MIC=0.61).

1.2.8.1 Going further: Dynamic Time Warping

MIC will not be helpful for more complex esenarios having time series which vary in speed, you would usedynamic time warping technique (DTW).

Let’s use an image to catch up the concept visually:

Figure 1.15: Dynamic time warping

Image source:Dynamic time wrapping Converting images into time series for data mining(Izbicki2011).

The last image shows two different approaches to compare time series, and theeuclidean is more similar to MIC measure. While DTW can track similarities occurring at different times.

A nice implementation inR:dtw package.

Finding correlations between time series is another way of performingtime series clustering.

1.2.9 Correlation on categorical variables

MINE -and many other algorithms- only work with numerical data. We need to do adata preparation trick, converting every categorical variable into flag (or dummy variable).

If the original categorical variable has 30 possible values, it will result in 30 new columns holding the value0 or1, when1 represents the presence of that category in the row.

If we use packagecaret from R, this conversion only takes two lines of code:

library(caret)# selecting just a few variablesheart_disease_2 =select(heart_disease, max_heart_rate, oldpeak, thal, chest_pain,exer_angina, has_heart_disease)# this conversion from categorical to a numeric is merely# to have a cleaner plotheart_disease_2$has_heart_disease=ifelse(heart_disease_2$has_heart_disease=="yes",1,0)# it converts all categorical variables (factor and# character for R) into numerical variables.# skipping the original so the data is ready to usedmy =dummyVars(" ~ .",data = heart_disease_2)heart_disease_3 =data.frame(predict(dmy,newdata = heart_disease_2))# Important: If you recieve this message# `Error: Missing values present in input variable 'x'.# Consider using use = 'pairwise.complete.obs'.`# is because data has missing values.# Please don't omit NA without an impact analysis first,# in this case it is not important.heart_disease_4=na.omit(heart_disease_3)# compute the mic!mine_res_hd=mine(heart_disease_4)Printing a sample…

mine_res_hd$MIC[1:5,1:5]## max_heart_rate oldpeak thal.3 thal.6 thal.7## max_heart_rate 1.00 0.24 0.244 0.120 0.184## oldpeak 0.24 1.00 0.175 0.111 0.157## thal.3 0.24 0.18 0.992 0.073 0.710## thal.6 0.12 0.11 0.073 0.327 0.044## thal.7 0.18 0.16 0.710 0.044 0.964Where columnthal.3 takes a value of 1 whenthal=3.

1.2.9.1 Printing some fancy plots!

We’ll usecorrplot package in R which can plot acor object (classical correlation matrix), or any other matrix. We will plotMIC matrix in this case, but any other can be used as well, for example,MAS or another metric that returns an squared matrix of correlations.

The two plots are based on the same data but display the correlation in different ways.

# library wto plot that matrixlibrary(corrplot)## corrplot 0.84 loaded# to use the color pallete brewer.pallibrary(RColorBrewer)# hack to visualize the maximum value of the# scale excluding the diagonal (variable against itself)diag(mine_res_hd$MIC)=0# Correlation plot with circles.corrplot(mine_res_hd$MIC,method="circle",col=brewer.pal(n=10,name="PuOr"),# only display upper diagonaltype="lower",#label color, size and rotationtl.col="red",tl.cex =0.9,tl.srt=90,# dont print diagonal (var against itself)diag=FALSE,# accept a any matrix, mic in this case#(not a correlation element)is.corr = F )

Figure 1.16: Correlation plot

# Correlation plot with color and correlation MICcorrplot(mine_res_hd$MIC,method="color",type="lower",number.cex=0.7,# Add coefficient of correlationaddCoef.col ="black",tl.col="red",tl.srt=90,tl.cex =0.9,diag=FALSE,is.corr = F )

Figure 1.16: Correlation plot

Just change the first parameter -mine_res_hd$MIC- to the matrix you want and reuse with your data.

1.2.9.2 A comment about this kind of plots

They are useful only when the number of variables are not big. Or if you perform a variable selection first, keeping in mind that every variable should be numerical.

If there is some categorical variable in the selection you can convert it into numerical first and inspect the relationship between the variables, thus sneak peak how certain values in categorical variables are more related to certain outcomes, like in this case.

1.2.9.3 How about some insights from the plots?

Since the variable to predict ishas_heart_disease, it appears something interesting, to have a heart disease is more correlated tothal=3 than to valuethal=6.

Same analysis for variablechest_pain, a value of 4 is more dangerous than a value of 1.

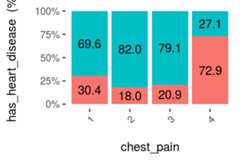

And we can check it with other plot:

cross_plot(heart_disease,input ="chest_pain",target ="has_heart_disease",plot_type ="percentual")

Figure 1.17: Visual analysis using cross-plot

The likelihood of having a heart disease is 72.9% if the patient haschest_pain=4. More than 2x more likely if she/(he) haschest_pain=1 (72.9 vs 30.4%).

Some thoughts…

The data is the same, but the approach to browse it is different. The same goes when we are creating a predictive model, the input data in theN-dimensional space can be approached through different models like support vector machine, a random forest, etc.

Like a photographer shooting from different angles, or different cameras. The object is always the same, but the perspective gives different information.

Combining raw tables plus different plots gives us a more real and complementary object perspective.

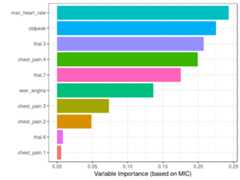

1.2.10 Correlation analysis based on information theory

Based on MIC measure, mine function can receive the index of the column to predict (or to get all the correlations against only one variable).

# Getting the index of the variable to# predict: has_heart_diseasetarget="has_heart_disease"index_target=grep(target,colnames(heart_disease_4))# master takes the index column number to calculate all# the correlationsmic_predictive=mine(heart_disease_4,master = index_target)$MIC# creating the data frame containing the results,# ordering descently by its correlation and excluding# the correlation of target vs itselfdf_predictive =data.frame(variable=rownames(mic_predictive),mic=mic_predictive[,1],stringsAsFactors = F)%>%arrange(-mic)%>%filter(variable!=target)# creating a colorful plot showing importance variable# based on MIC measureggplot(df_predictive,aes(x=reorder(variable, mic),y=mic,fill=variable) )+geom_bar(stat='identity')+coord_flip()+theme_bw()+xlab("")+ylab("Variable Importance (based on MIC)")+guides(fill=FALSE)

Figure 1.18: Correlation using information theory

Although it is recommended to run correlations among all variables in order to exclude correlated input features.

1.2.10.1 Practice advice for usingmine

If it lasts too much time to finish, consider taking a sample. If the amount of data is too little, consider setting a higher number inalpha parameter, 0.6 is its default. Also, it can be run in parallel, just settingn.cores=3 in case you have 4 cores. A general good practice when running parallel processes, the extra core will be used by the operating system.

1.2.11 But just MINE covers this?

No. We used only MINE suite, but there are other algortihms related tomutual information. In R some of the packages are:entropy andinfotheo.

PackagefunModeling (from version 1.6.6) introduces the functionvar_rank_info which calculates several information theory metrics, as it was seen in sectionRank best features using information theory.

InPython mutual information can be calculated through scikit-learn,here an example.

The concept transcends the tool.

1.2.11.1 Another correlation example (mutual information)

This time we’ll useinfotheo package, we need first to do adata preparation step, applying adiscretize function (or binning) function present in the package. It converts every numerical variable into categorical based on equal frequency criteria.

Next code will create the correlation matrix as we seen before, but based on the mutual information index.

library(infotheo)# discretizing every variableheart_disease_4_disc=discretize(heart_disease_4)# calculating "correlation" based on mutual informationheart_info=mutinformation(heart_disease_4_disc,method="emp")# hack to visualize the maximum value of the scale excluding the diagonal (var against itself)diag(heart_info)=0# Correlation plot with color and correlation Mutual Information from Infotheo package. This line only retrieves the plot of the right.corrplot(heart_info,method="color",type="lower",number.cex=0.6,addCoef.col ="black",tl.col="red",tl.srt=90,tl.cex =0.9,diag=FALSE,is.corr = F)

Figure 1.19: Comparing variable importance

Correlation score based on mutual information ranks relationships pretty similar to MIC, doesn’t it?

1.2.12 Information Measures: A general perspective

Further than correlation, MIC or other information metric measure if there is afunctional relationship.

A high MIC value indicates that the relationship between the two variables can be explained by a function. Is our job to find that function or predictive model.

This analysis is extended to n-variables, this book introduces another algorithm in the selecting best variables chapter.

Some predictive models perform better than other, but if the relationship is absolutely noisy no matter how advance the algorithm is, it will end up in bad results.

More to come onInformation Theory. By now you check these didactical lectures:

- 7-min introductory videohttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2s3aJfRr9gE

- http://alex.smola.org/teaching/cmu2013-10-701x/slides/R8-information_theory.pdf

- http://www.scholarpedia.org/article/Mutual_information

1.2.13 Conclusions

Anscombe’s quartet taught us the good practice of getting theraw statistic together with a plot.

We could see hownoise can affect the relationship between two variables, and this phenomenon always appears in data. Noise in data confuses the predictive model.

Noise is related to error, and it can be studied with measures based on information theory such asmutual information andmaximal information coefficient, which go one further step than typical R squared. There is a clinical study which uses MINE as feature selector in(Caban et al.2012).

These methods are applicable infeature engineering as a method which does not rely on a predictive model to rank most important variables. Also applicable to cluster time series.

Next recommended chapter:Selecting best variables

References

McNeese, Bill. 2016. “Are the Skewness and Kurtosis Useful Statistics?”https://www.spcforexcel.com/knowledge/basic-statistics/are-skewness-and-kurtosis-useful-statistics.

Handbook, Engineering Statistics. 2013. “Measures of Skewness and Kurtosis.”http://www.itl.nist.gov/div898/handbook/eda/section3/eda35b.htm.

Reshef, David N., Yakir A. Reshef, Hilary K. Finucane, Sharon R. Grossman, Gilean McVean, Peter J. Turnbaugh, Eric S. Lander, Michael Mitzenmacher, and Pardis C. Sabeti. 2011. “Detecting Novel Associations in Large Data Sets.”Science 334 (6062): 1518–24. doi:10.1126/science.1205438.

Wikipedia. 2017b. “Monotonic Function.”https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monotonic_function.

Izbicki, Mike. 2011. “Converting Images into Time Series for Data Mining.”https://izbicki.me/blog/converting-images-into-time-series-for-data-mining.html.

Caban, Jesus J., Ulas Bagci, Alem Mehari, Shoaib Alam, Joseph R. Fontana, Gregory J. Kato, and Daniel J. Mollura. 2012. “Characterizing Non-Linear Dependencies Among Pairs of Clinical Variables and Imaging Data.”Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2012 (August): 2700–2703. doi:10.1109/EMBC.2012.6346521.