byJogendra

As a Golang developer, you probably have encountered import cycles. Golang do not allow import cycles. Go throws a compile-time error if it detects the import cycle in code. In this post, let’s understand how the import cycle occurs and how you can deal with them.

To truly appreciate why Go disallows import cycles, it’s crucial to understand its compilation model.

When you compile a Go program, thego build command (orgo install,go run) performs several steps:

main package or the package being compiled).This ordered compilation works because Go is designed with a strict acyclic dependency graph (DAG) in mind. Each package is compiled exactly once, and its compiled output (an archive file, typically.a) is then used by packages that import it.

At its core, an import cycle occurs when two or more packages directly or indirectly depend on each other.

Let’s illustrate with the simplest scenario involving two packages, p1 and p2:

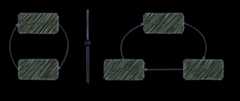

Direct Cycle: Packagep1 importsp2, andp2 importsp1. This forms a direct cycle of dependency.The problem can also be more complex, involving multiple packages in a chain:

Indirect Cycle: Packagep1 importsp2,p2 importsp3, andp3 then importsp1. Even thoughp1 andp2 don’t directly import each other, a cycle is still formed throughp3.

Visually, an import cycle creates a closed loop in your project’s dependency graph:

Let’s understand it through some example code.

Package p1:

packagep1import("fmt""import-cycle-example/p2")typePP1struct{}funcNew()*PP1{return&PP1{}}func(p*PP1)HelloFromP1(){fmt.Println("Hello from package p1")}func(p*PP1)HelloFromP2Side(){pp2:=p2.New()pp2.HelloFromP2()}Package p2:

packagep2import("fmt""import-cycle-example/p1")typePP2struct{}funcNew()*PP2{return&PP2{}}func(p*PP2)HelloFromP2(){fmt.Println("Hello from package p2")}func(p*PP2)HelloFromP1Side(){pp1:=p1.New()pp1.HelloFromP1()}On building, compiler returns the error:

imports import-cycle-example/p1imports import-cycle-example/p2imports import-cycle-example/p1: import cycle not allowedThis error clearly indicates the presence of a circular dependency betweenp1 andp2.

Go is highly focused on faster compile time rather than speed of execution (even willing to sacrifice some run-time performance for faster build). The Go compiler doesn’t spend a lot of time trying to generate the most efficient possible machine code, it cares more about compiling lots of code quickly.

Allowing cyclic/circular dependencies wouldsignificantly increase compile times since the entire circle of dependencies would need to get recompiled every time one of the dependencies changed. It also increases the link-time cost and makes it hard to test/reuse things independently (more difficult to unit test because they cannot be tested in isolation from one another). Cyclic dependencies can result in infinite recursions sometimes.

Cyclic dependencies may also cause memory leaks since each object holds on to the other, their reference counts will never reach zero and hence will never become candidates for collection and cleanup.

Robe Pike, replying to proposal for allowing import cycles in Golang, said that, this is one area where up-front simplicity is worthwhile. Import cycles can be convenient but their cost can be catastrophic. They should continue to be disallowed.

The worst thing about the import cycle error is, Golang doesn’t tell you source file or part of the code which is causing the error. So it becomes tough to figure out when the codebase is large. You would be wondering around different files/packages to check where actually the issue is. Why golang do not show the cause that causing the error? Because there is not only a single culprit source file in the cycle.

But it does show the packages which are causing the issue. So you can look into those packages and fix the problem.

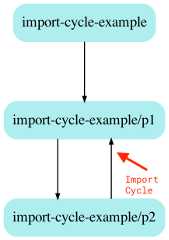

To visualize the dependencies in your project, you can usegodepgraph, a Go dependency graph visualization tool. It can be installed by running:

go get github.com/kisielk/godepgraphIt display graph inGraphviz dot format. If you have the graphviz tools installed (you can download fromhere), you can render it by piping the output to dot:

godepgraph -s import-cycle-example | dot -Tpng -o godepgraph.pngYou can see import cycle in output png file:

Apart from it, you can usego list to get some insights (rungo help list for additional information).

go list -f '{\{join .DepsErrors "\n"\}}' <import-path>You can provide import path or can be left empty for current directory.

Modern Go IDEs like VS Code with the Go extension or GoLand often provide features to visualize package dependencies and can sometimes highlight import cycles directly within the editor. This can be a very convenient way to spot issues early.

When you encounter the import cycle error, take a step back, and think about the project organization. The obvious and most common way to deal with the import cycle is implementation through interfaces. But sometimes you don’t need it. Sometimes you may have accidentally split your package into several. Check if packages that are creating import cycle are tightly coupled and they need each other to work, they probably should be merged into one package. In Golang, a package is a compilation unit. If two files must always be compiled together, they must be in the same package.

p1 to use functions/variables from packagep2 by importing packagep2.p2 to call functions/variables from packagep1 without having to import packagep1. All it needs to be passed packagep1 instances which implement an interface defined inp2, those instances will be views as packagep2 object.That’s how packagep2 ignores the existence of packagep1 and import cycle is broken.

After applying steps above, packagep2 code:

packagep2import("fmt")typepp1interface{HelloFromP1()}typePP2struct{PP1pp1}funcNew(pp1pp1)*PP2{return&PP2{PP1:pp1,}}func(p*PP2)HelloFromP2(){fmt.Println("Hello from package p2")}func(p*PP2)HelloFromP1Side(){p.PP1.HelloFromP1()}And packagep1 code look like:

packagep1import("fmt""import-cycle-example/p2")typePP1struct{}funcNew()*PP1{return&PP1{}}func(p*PP1)HelloFromP1(){fmt.Println("Hello from package p1")}func(p*PP1)HelloFromP2Side(){pp2:=p2.New(p)pp2.HelloFromP2()}You can use this code inmain package to test.

packagemainimport("import-cycle-example/p1")funcmain(){pp1:=p1.PP1{}pp1.HelloFromP2Side()// Prints: "Hello from package p2"}You can find full source code on GitHub atjogendra/import-cycle-example-go

Benefits of the this approach:

p2, allowingp2 to be tested in isolation.pp1Interface in the future.Other way of using the interface to break cycle can be extracting code into separate 3rd package that act as bridge between two packages. But many times it increases code repetition. You can go for this approach keeping your code structure in mind.

How it works:

m1: This package contains only the interfaces, shared types, or constants that bothp1 andp2 need.m1 should not importp1 orp2.p1 andp2 importm1: Both original packages now import m1 to access the common definitions.p1 -> m1 andp2 -> m1. The cycle is broken becausem1 doesn’t depend onp1 orp2.“Three Way” Import Chain: Package p1 -> Package m1 & Package p2 -> Package m1

This approach often leads to cleaner code when the shared abstraction is truly general-purpose. However, be mindful of “anemic” packages (packages with only interfaces and no concrete logic), as they can sometimes increase complexity.

Interestingly, you can avoid importing package by making use ofgo:linkname.go:linkname is compiler directive (used as//go:linkname localname [importpath.name]). This special directive does not apply to the Go code that follows it. Instead, the//go:linkname directive instructs the compiler to use“importpath.name” as the object file symbol name for the variable or function declared as“localname” in the source code. (definition fromgolang.org, hard to understand at first sight, look at the source code link below, I tried solving import cycle using it.)

There are many Go standard package rely on runtime private calls usinggo:linkname. You can also solve import cycle in your code sometime with it but you should avoid using it as it is still a hack and not recommended by the Golang team.This approach is also loss of type safety, means the compiler won’t check if the types you’re linking are compatible, leading to potential runtime errors.

Point to note here is Golang standard packagedo not usego:linkname to avoid import cycle, rather they use it to avoid exporting APIs that shouldn’t be public.

Here is the source code of solution which I implemented usinggo:linkname :

->jogendra/import-cycle-example-go -> golinkname

The import cycle is definitely a pain when the codebase is large. Try to build the application in layers. The higher-level layer should import lower layers but lower layers should not import higher layer (it create cycle). Keeping this in mind and sometimes merging tightly coupled packages into one is a good solution than solving through interfaces. But for more generic cases, interface implementation is a good way to break the import cycles.

You can checkout interestingdiscussion about this blog post on Reddit here.

I hope you got a fair understanding of Import Cycles. Do share and reach out to me onTwitter in case of anything. You can follow my open source work atgithub/jogendra. Thanks for the read :)

Subscribevia RSS