The Carbon Brief Profile: Democratic Republic of the Congo

As part of a long-runningseries profiling countries with the highest greenhouse gas emissions, Carbon Brief looks at the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) which, despite using hardly any fossil fuels, is one of the largest sources of emissions in Africa.

ByJosh Gabbatiss and Giuliana Viglione

Design byJoe Goodman and Kerry Cleaver

First published:

Updated:

The DRC is home toaround 60% of the second-largest rainforest on the planet, as well as much of the world’slargest tropical peatland, the Cuvette Centrale.

While the country’s land and forests are still a carbon sink overall, human-caused land use changes release large volumes of carbon dioxide (CO2) and make the DRC the world’s 16th biggest greenhouse gas emitter, as of 2023.

This means the DRC occupies an unusual position. Despite its high emissions, the country faces widespread poverty and only one-fifth of the population has electricity access.

Carbon Brief Country Profiles

Select a country from the series

As a result, when only consideringfossil fuels and industry, it has the world’s lowest per-capita carbon footprint.

On the world stage, the government has styled the DRC as a “solution country” for climate change, due to its carbon-dense forests andwealth of minerals required for clean technologies. At the same time, the nation’s leaders are also pushing logging and oil exploration as much-needed sources of investment.

The DRC government has also made it clear that any efforts to preserve the nation’s rainforest and build low-carbon power will be heavily reliant on financial support from wealthier nations.

The DRC is one of the most vulnerable countries in the world when it comes to the impacts of climate change, and its preparedness is hampered by the lack of historical or current weather measurements.

- Politics

- Paris pledge

- Forests and land use

- Peatlands

- Mining

- Energy access

- Renewables

- Fossil fuels

- Climate finance

- Impacts and adaptation

- Notes

Politics

The DRCsaw its first peaceful transition of power after the 2018 general election, following decades of post-colonial struggles, dictatorship and war.

Another election took place at the end of 2023. The incumbent president, Félix Tshisekedi, held onto power, amidaccusations of electoralfraud and logistical issues.

The environment has not traditionally been a key political issue in the DRC and overtly “green” parties are not major players. However, in recent years leaders haveincreasingly made the links between tackling poverty and addressing climate change.

Around 99 million people from over 200 different ethnic groupslive in the DRC, placing it among the most populous andculturally diverse countries in the world. It is also the largest country in sub-Saharan Africa, occupying an area greater than western Europe.

Despite its wealth of natural resources, the country remains one of the poorest in the world, with among thelowest rates of electricity access. It has the13th-lowest GDP per capita of any country and is classified by the UN as a “least developed country”.

Throughout its history, DRC’s resource wealth has beenconsistently linked to human rights violations and has done little to raise the living standards of ordinary Congolese people.

The government saysit wants the DRC to be an emerging economy by 2030,with a “vision of development” based on becoming an “increasingly low-carbon economy”.

Félix-Antoine Tshisekedi Tshilombo, President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Credit: Enrique Shore /Alamy Stock Photo.

Following colonisation in the 19th century, the region wasbrutally run by King Leopold II of Belgium as his private property before being taken over as an official Belgian colony. This periodwas marked by the violent exploitation of the nation’s resources.

The nation gained its independence in 1960, but the DRC’s first democratically elected prime minister, Patrice Lumumba, wasopposed by the US and Belgium. He wasultimately murdered following a western-backed military coup led by his military aide Joseph Mobutu (later known as Mobutu Sese Seko).

Mobutu’s subsequent dictatorship lasted until 1997, when he wasoverthrown in the First Congo War.

This, and the Second Congo War that lasted until 2003, drew in nations across the continent, displacing millions of people and causingmore deaths than any conflict since the Second World War. These wars have also been linked towidespread destruction of nature andforest loss across an area at least the size of Belgium.

While Tshisekedi has overseen a period ofrelative stability, conflict haspersisted in the east of the country,largely due to Rwanda-backed “M23” rebels operating in the region.

The DRC is a semi-presidential republic,with a lower house called the National Assembly and an upper house called the Senate, similar to the model usedin France. The president serves as head of state, but they pick a prime minister to act as head of government.

Tshisekedi, who leads the nation’s oldest and largest political party, the Union for Democracy and Social Progress, came to power in 2018 amid reports of a “backroom deal” with hiscontroversial predecessor, Joseph Kabila. (Transparency Internationalranks the DRC as among the most corrupt nations in the world.)

As of 2021, the president had established a new majority coalition dubbed the “Sacred Union”, which includes former rivals and Kabila supporters.

Among them is deputy prime ministerÈve Bazaiba, from the nationalist Movement for the Liberation of Congo, who also serves as environment and sustainable development minister and hasvocally represented the DRC at international climate events.

Overall, climate policy in the DRC suffers from “a lack of cohesion and unifying objectives, due to the lack of a national climate strategy” to provide structure, according to environmental researcherProf Cush Ngonzo Luwesi, writing in a 2020 edition of the Congolese magazineLes Mérites d’Afrique.

Climate-related policy in the DRC has largely formed part of a push for “sustainable development”, as successive governments have sought ways to make use of the nation’s rich natural resources and improve people’s living standards.

The nation’sEnvironment Protection Law in 2011 emphasised that the state and provinces should take “necessary” measures to cut emissions and adapt to climate change.

In the second update to itsgrowth and poverty reduction strategy, released around the same time, the government included a “new pillar” – “the protection of the environment and the fight against climate change”.

Thenational strategic development plan, covering the period 2019 to 2023, was released by Tshisekedi to set out the agenda for his presidency. Climate action alongside “sustainable and balanced development” was once again a core “pillar” of the strategy.

In 2021, upon her appointment as environment minister, Bazaiba set out a10-point programme focused mainly on climate-related measures for the natural resources sector.

Eve Bazaiba Masudi, vice-prime minister and environment minister of the Democratic Republic of Congo at the COP15 UN conference on biodiversity in Montreal. Credit: The Canadian Press /Alamy Stock Photo.

Among other things, this programme contained plans to institute a carbon tax and create a regulatory authority for carbon markets. It alsoincluded plans for a national forest policy for the DRC, and launched studies exploring a national climate change policy.

Paris pledge

The DRC’s annual greenhouse gas emissions were 554m tonnes of CO2 equivalent (MtCO2e) in 2023, according to a database published inScientific Data by Dr Matthew Jones of the University of East Anglia and collaborators.

This also means that DRC citizens have per capita emissions of 5.2 tonnes of CO2e, comparable to the UK or France.

However, unlike most major emitters, nearly all of these emissions – more than 90% – come from human activities in the land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF) sector. This islargely the result of forest loss driven by small-scale agriculture.

This data only accounts for human activities on the land, rather thannatural processes. Overall, the Congo rainforest still absorbs more carbon than it releases, although its status as a “carbon sink” is under threat. (See:Forests.)

There issignificant uncertainty around LULUCF emissions data and other estimates place overall human-driven land use emissionshigher. The DRC governmentstates that its 2018 LULUCF emissions were 529MtCO2e.

Virtually all of the DRC’s remaining emissions come from methane seeping out of landfills and other waste disposal sites. CO2 emissions from energy use are negligible.

In fact, when only considering emissions from fossil fuels and industry, the DRC has thelowest per-capita emissions in the world – just 0.03 tonnes of CO2 in 2022.

DRC has submitted anupdated international climate pledge (nationally determined contribution, NDC) under the Paris Agreement.

It is targeting a 21% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, compared to a business-as-usual scenario, an improvement on itsprevious NDC goal of a 17% reduction. Under this plan, emissions at the end of the decade would still be higher than they are today.

Only 2% of this 21% reduction is described as “unconditional”, meaning the remainder relies on the DRC receiving money and technical assistance from wealthy nations (see:Climate finance).

The nation has had a relatively prominent role in recent UN negotiations both for climateand biodiversity.

In 2022, ahead of theCOP27 climate summit, the government hosted the “pre-COP” in the capital city, Kinshasa, where itpresented the DRC as a “solution country” for climate change.

The DRC is a member of severalnegotiating alliances during UN climate negotiations, including theAfrican Group of Negotiators, theLeast Developed Countries (LDCs), theGroup of 77 plus China (G77 plus China) and theCoalition of Rainforest Nations.

Congolese economist and negotiatorTosi Mpanu-Mpanu has been a notable figure at COP events over the years,serving as chair of the LDCs in 2016 and chair of the UN’sSubsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice in 2022.

Tosi Mpanu-Mpanu, climate ambassador for the Democratic Republic of Congo. Credit:IISD/ENB | Diego Noguera.

Forests and land use

With a surface area of 2.3m square kilometres (km2), the DRC is Africa’s second-largest country.

It sits within theCongo Basin in central Africa and stretches across the equator. The basin and its dense forests – it holds the second-largest rainforest in the world – encompass much of the country, but the DRC also contains high plateaus and mountain peaks, especially in the eastern part of the country.

Land-use change dominates the DRC’s emissions profile, positioning it as the world’s 12th-highest emitting country, despite low fossil fuel use. More than 90% of its 544MtCO2e emissions in 2019 came from land-use change. (For more information about the nation’s emissions, see:Paris pledge.)

Various estimates put the amount of forest in the DRC betweenhalf andtwo-thirds of its total area. About 15% is used for agriculture, and the remainder is largely grass- or shrubland.

Nearly 325,000km2 – almost 14% – of the country’s land is contained within more than 50protected areas. This includes four areas designated as wetlands of international importance under theRamsar Convention.

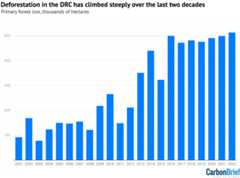

According toGlobal Forest Watch, the DRC has lost 6.33m hectares of primary forest, or just over 6% of its total, since 2002. Including secondary forest, it lost a total of 18.4m hectares of tree cover between 2001-22, equivalent to 11.4GtCO2e – an average of 517MtCO2e per year.

In a2018 study of the world’s three largest rainforest nations – Brazil, the DRC and Indonesia – researchers found the smallest amount of primary forest loss in the DRC over the period 2002-14 but noted that “its forests are increasingly encroached upon”.Observational evidence from six tropical African countries, including the DRC, has suggested that those forests may be more resilient to climatic extremes than the Amazon or tropical forests in Asia.

A separate2018 study based on satellite imagery of the region found that more than 90% of deforestation in the DRC was attributable to small-scale shifting cultivation.

Undershifting cultivation, small areas of forest are cleared to make space for crops, releasing CO2 in the process. After some time, the fields are left to fallow and regrow, at which point they take up CO2 again. This creates what is known as the “rural complex” – a patchwork of secondary forest, both active and fallow fields, roads and settlements.

However, much of the smallholder-driven forest loss occurs in already-degraded secondary forests, while industrial activities are more likely to drive deforestation in primary forests, according to theCongo Basin Forest Declaration Assessment.

The assessment adds that large-scale agriculture, logging and industrial mining “pose the gravest risks to core intact forests”. Beyond the direct impact of these activities, they open remote, “previously inaccessible” parts of the forest to further development.

Food insecurity is rampant in the country, whichimports more than $1bn of food per year.

Only a tenth of the country’s arable cropland iscurrently used. In 2014, the government launched anew initiative aimed at expanding industrial agriculture by converting nearly 18,000km2 of the country into “agro-industrial parks”.

The initiative’s pilot project, a park calledBukanga Lonzo, wasplagued with corruption and ultimately collapsed within three years.

A small village near Pweto, Katanga, in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Credit: Alphorom /Alamy Stock Photo.

Protection of the DRC’s carbon-rich rainforests was one of the central pledges of the Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests, announced at theCOP26 climate summit in November 2021.

In 2021, environment minister and deputy prime minister Bazaibaannounced ten “urgent measures” for natural resource management.

These included several forestry-specific measures, including the development of a national forest policy, banning exports of timber and assessing previously granted logging concessions. In October 2021, Bazaiba “announced the suspension of log exports…but did not say when it would come into effect”,Reuters reported.

In April 2022, the DRC’s council of ministersapproved a new national land policy, which is meant to modernise land administration and “make it easier to prevent and resolve conflicts over land”,according to theGlobal Land Tool Network, a collection of groups including international organisations, philanthropies and research institutions with a commitment to increasing access to land.

The national assemblypassed a land-use planning law in October 2023, with an aim of promoting sustainable development and reducing conflicts based on land use.

Peatlands

The Congo Basin’sCuvette Centrale, which stretches across both the DRC and the Republic of the Congo, holdsmore than one-third of the total tropical peatlands in the world, and stores nearly 30% of the global tropical peatland carbon stock.

The peatland complex stretches across nearly 150,000km2, with more than 90,000km2 held within the borders of the DRC.

Peat is made up of partially decomposed plant matter, built up over centuries. It is extremely carbon-dense: a2017 study, the first to map the basin’s peatlands, estimated that just over 30bn tonnes of carbon are stored beneath the surface of the Cuvette Centrale – approximately the same amount of carbon stored aboveground in the tropical forests of the Congo Basin. Around 19bn tonnes of the peatland carbon are in the DRC.

The DRC and the neighbouring Republic of the Congo are the “second and third most important countries in the tropics for peat areas and carbon stocks, after Indonesia”, according to the study.

In 2018, both countries – as well as Indonesia, which holds another third of the world’s tropical peatlands and has significant experience managing said peatlands – signed theBrazzaville Declaration. This seeks to promote better management practices and conservation of the Cuvette Centrale’s peatlands.

The DRC also supported and signed the 2019UN environment assemblyresolution on the conservation and sustainable management of peatlands.

In a2018 study, researchers outlined potential threats to the Cuvette Centrale and priorities for its conservation. Theywrote:

“The low level of human intervention at present suggests that the opportunity still exists to protect the peatlands in a largely intact state.”

Tropical rainforest and meandering river in Salonga National Park, Democratic Republic of Congo. Credit: Nature Picture Library /Alamy Stock Photo.

TheSpecial Report on Climate Change and Land from theIntergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) notes that “expansion of agriculture is not yet a major factor” in driving peatland degradation in Africa. Rather, the “principle threat” to these peat deposits lies in shifting rainfall patterns due to climate change, the report says.

In October 2021, the DRC submitted anupdated climate pledge, which includes a focus on protecting the country’s peatlands. Itincludes directives to both map and assess the peatlands, as well as restore degraded areas and to “not allocating industrial agricultural concessions in high-value forests and in peatlands”.

However, a2021 report from theUS Agency for International Development,US Department of Agriculture and the Congolese non-governmental organisation theCouncil for Environmental Defense through Legality and Traceability noted that “currently, there is no peatland-specific strategy, policy or legislation” in the country and that developing one was a “priority” for the DRC.

The report made a number of recommendations, including that the country “clearly define principles of legal protection” in a national peatland strategy, provide “clear protections…through legislative reform” and take into account local communities who have traditionally called the peatlands their home.

Mining

The DRC isone of the richest countries in the world in terms of natural resources. It is home to a wealth of mineral and precious metal deposits, with an estimated $24tn of resources still buried beneath the country’s surface, according to the USInternational Trade Administration.

Today, extractive industries make up around 90% of thecountry’s exports and nearly half of its government’s revenue; around half of its total exports are traded to China. Chief among itsexports are cobalt, copper, gold, diamonds andcoltan, which is an ore of the metalsniobium and tantalum.

The mining sector is also a keydriver of economic growth in the DRC. However, the reliance of the DRC’s economy on resource exports also means that its economy is subject to fluctuations in global markets.

In 2020, the DRCmined around 100,000 tonnes of cobalt – about 70% of total global production.

Cobalt is a key mineral for many types of batteries, including those often found in electric vehicles, phones and other rechargeable batteries. But EV makers are increasingly turning towards batteries with lower cobalt requirements, according to theIEA.

Up toone-quarter of the country’s cobalt production is carried out by “artisanal” or small-scale miners. Investigations have revealed numerous human-rights abuses incopper,cobalt andgold mining across the country. Illegal gold mining is alsorampant in the DRC.

Globally, nearly all cobalt ismined as a byproduct, with copper mining producing about 60% of cobalt and nickel mines producing nearly 30%.

The southern portion of the DRC cuts across the central AfricanCopperbelt, one of the world’s “most important copper-producing regions”, according to theUS Geological Survey.

The DRC’s copper deposits are among the highest-quality in the world and the countryproduced some 1.8m tonnes of the metal in 2021. It is Africa’s largest producer of the metal, exporting both refined and unrefined copper.

Control of mining areas has perpetuated conflict in the eastern part of the country. Areport(pdf) from the UN security council in March 2022 noted that “competition over control of mining sites…increasingly triggered conflict” between armed groups.

The country is also among the world’s top five producers of diamonds, despitedeclining production volumes over the past two decades. In 2022, the DRC produced 9.9m carats of diamonds – about one-third of the 30m carats the country produced in 2004.

In its refined form,coltan is used to make capacitors that are found in a range of consumer electronics. Coltan is a relativelysmall market, with global 2020 production totalling only 2,300 tonnes. Nearly one-third of this – 700 tonnes – was mined in the DRC.

Germanium hasmany applications across optics, catalysis and electronics. A new mine opened in the DRC in October 2023, with astated aim of producing 30% of the world’s germanium.

Open pit copper mine in the mineral-rich Shaba region of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Credit: Marion Kaplan /Alamy Stock Photo.

In 2018, the DRC updated its mining code, which lays out regulations as well as guiding principles for mining in the country. The law, which increased royalties on minerals and ores, washeavily opposed by foreign mining companies.

The updated mining code identified four “strategic metals” for the country: cobalt, coltan, germanium and lithium. Mining products falling under this designation are taxed at a higher rate than other minerals and ores.

TheKipushi mine, a major mine in the south-eastern part of the country, isreportedly slated to resume mining operations “by late 2024” after spending three decades under “care and maintenance”. Germanium, copper, zinc and silver will all be produced from the Kipushi mine, which is set to be powered by hydroelectric power.

Although the DRC does not currently make a significant contribution to global lithium export, it is home tolarge deposits of the metal, with 3m tonnes of identified resources, according to theUS Geological Survey – ranking seventh in the world.

Lithium production wasexpected to begin in the south-eastern part of the country as early as 2023, but has been held up by legal battles.

Australian mining companyAVZ Minerals had beengranted the rights to develop the Manono lithium mine, but those permissions were revoked in February 2023. The DRC mining ministry “said the company had not developed it fast enough”, according toReuters. The rights were then re-issued to the Chinese mining companyZijin Mining.

According to AVZ, the area of the prospective mine “stands as one of the largest and highest grade undeveloped hard-rock lithium deposits in the world”.

Energy access

The DRC possesses significant energy resources, includinghuge potential for hydroelectric and solar power, as well as oil and gas reserves. Despite this, it has very low rates of energy access, and this is a major barrier to poverty reduction.

Just 21% of the population had access to electricity in 2021, one of the lowest rates in the world, according to theWorld Bank. (TheInternational Energy Agency places this rate far lower, at just 9% in 2022, due to different data collection methods.)

There is a cleardivision in Congolese society, with around 41% of people in urban areas having access to electricity and just 1% in rural areas. Yet even in cities, people and companiesoften rely on expensive diesel generators for power, due to inadequate infrastructure.

Historically, when power capacity has increased it has often been funded by and built to supply mining facilities.More than half of the electricity consumed in the country is used by industry, rather than in people’s homes and local businesses.

Polling by the World Bank found that nearly nine out of 10 firms in the DRC experience power outages and half identified electricity as a major constraint to growth.

The state-owned utility companySociété Nationale d’Électricité (SNEL) is a key provider of electricity, particularly in the capital city of Kinshasa. However, it isburdened with debt and deteriorating hydropower assets.

The government hassaid it is targeting improved access to power by seeking development funds and requiring companies serving mines to also provide electricity to local communities.

Two years ago, the International Finance Corporation said the DRC government wasaiming to connect 30% of the population to power by 2024, up from 19% in 2019. (As noted above, the most recent figure, for 2021, stood at 21%.)

Field technician checks a connection on an electrical pole in Goma, DRC. Credit: Global Press /Alamy Stock Photo

Meanwhile, theWorld Health Organisationestimates that only around 4% of people in the DRC have access to clean fuels for cooking.

Instead, they largely rely on charcoal, which is produced by cutting and burning wood, and therefore alsocontributes to deforestation (see:Forests and land use). As of 2020, 94% of the nation’s energy use consisted of people burning biofuels in this manner, according to theIEA.

Energy use in the transport sector is also very low, in part because there are so few roads criss-crossing the densely forested nation. The DRC hasapproximately the same sized network of paved roads as Luxembourg, a nation 1,000 times smaller.

This lack of roads can in turn make energy infrastructure projects difficult to manage. Much of the transport of people and goods in the DRC is conducted on boats via its expansive river network.

Renewables

The DRC hasenormous renewable energy potential, which is largely untapped.

It could theoretically build enough hydropower dams to “light up a significant portion of Africa”,according to theInternational Hydropower Association.

The Congo River, which traverses the nation, has the second largest flow of any river in the world after the Amazon. Its hydroelectric potential has beenestimated at 100 gigawatts (GW).

Despite the DRC only having developed a fraction of its potential, hydropower dams currently provide virtually all of the country’s roughly 13 terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity, as the chart below shows. This figure is around 40 times less electricity than generated in Germany – a nation with a smaller population.

President Tshisekedi has expressed an interest in further developing hydropower,describing it as “undoubtedly the most suitable type of electricity to support our country’s long-term development priorities”.

As it stands, the nation’s two main hydroelectric dams, Inga 1 and Inga 2, have a combined capacity of less than 2GW. They were built in the 1970s and 1980s under the dictator Mobutu and, since then, have fallen into disrepair, working at well below their maximum capacity.

The dams have also contributed tosocial problems. The main power line that links the dams with minespushed the country further into debt.

Nevertheless, for years there has beendiscussion of expanding the Inga dams further into a so-called “Grand Inga Dam”. This proposed project would have a capacity of 40GW, making it the largest hydroelectric scheme in the world.

The first phase of this expansion, Inga 3, hasfaced years of delays and struggled to attract long-term investment since it was announced in 2004. Funders haverepeatedlypulled out of the project.

A motorcyclist transports a solar panel in dense traffic in the megacity of Bukavu in Eastern Congo. Creidt: Kay Nietfeld / dpa picture alliance /Alamy Stock Photo.

Even if the 4.8GW Inga 3 project is constructed,critics havepointed out that it will not provide greater electricity access to Congolese people, as it isexplicitly being built to serve industry and tosell electricity to South Africa.

The DRC also has significant unused potential for other renewables, particularly solar power. Onestudy concluded that at least 70GW of solar power could be built within 25km of existing and planned transmission lines across the country.

As of 2022, however, the nation had only 20 megawatts (0.02GW) of solar capacity,according to theInternational Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA).

Given the nation’s large and dispersed population, weak governance and dense forest, many haveargued that off-grid solar provides the best opportunity for boosting electricity access, particularly for people outside of urban centres.

The governmenthas expressed interest in expanding the DRC’s solar capacity and the electricity sector law agreed in 2014 explicitlyhighlights the importance of off-grid renewables for rural regions.

Foreigninvestment in DRC solarhas beenramping up in recent years, includingprojects that run into the hundreds of MW.

Fossil fuels

The DRC does not burn any coal or gas, and was using just 18,000 barrels of oil per day as of 2021, according to theUS Energy Information Administration (EIA).

For comparison, Germany uses around 100 times more oil per day despite being home to fewer people. The US uses over 1,000 times more oil per day.

The African nation produces a small amount of oil, all of which is exported. The Anglo-French companyPerenco operates a handful of onshore and offshore fields along the DRC’s small Atlantic coastline.

In 2021, just 22,000 barrels of oil wereextracted each day in the DRC. That year, the UK was producing 40 times as many barrels and the US was producing 1,000 times as many. Even the Republic of Congo, which is around seven times smaller than its neighbour, extracts around 10 times as much oil as the DRC.

All of this means that DRC’s emissions from using fossil fuels are negligible.

However, the nation has thesecond-largest reserves of oil in south and central Africa.For years, leaders have looked to expand drilling into the DRC’s forested interior.

In 2022, the nation wasonce again at the centre of a furore concerning plans to expand the land open to fossil fuel exploration. In April that year, DRC ministers approved the auction of 16 “blocks” of land for potential oil extraction – a number thatlater expanded to 27 oil blocks and three gas fields.

The governmenttouted billions of dollars worth of fossil fuel reserves available to anyforeign oil firms interested in exploring the region. Followingdelays, the first contracts were awarded in September 2023, withNGOs and journalists at theBureau of Investigative Journalism raising concerns about the companies involved.

These actions have faced significant backlashfrom hundreds of environmental organisations, both within the DRC and around the world. The groups pointed out that areas being auctioned offoverlap not only with carbon-rich peatlands and dense rainforest – including protected areas – but also Indigenous communities.

DRC leaders argued that they were trying to generate revenue for their people. Observers havepointed out that oil auctions have often been used ahead of elections as ways to quickly generate income.

At the time, Tosi Mpanu Mpanu, a diplomat and UN climate summit veteran, told theNew York Times that, in light of the nation’s poverty, “our priority is not to save the planet”.

In response, activists argued that the move contradicted deals made with wealthy countries to protect the rainforest in exchange for development aid (see: Climate finance).

They alsopointed to the “toxic legacy” of oil development by foreign companies, in African nations such as Nigeria, as a “cautionary tale” for the DRC.

Moreover, Congolese people living in the regions being auctioned for oil havetold NGOs that they were not consulted about the process – and do not expect to benefit.

Climate finance

DRC’s leaders havemade it clear that they see both fossil fuels and Congo rainforest exploitation as potential sources of money for development and poverty alleviation.

In this context, the DRC government said that the nation needs climate finance from wealthy countries to help protect its natural carbon stores. It has alsocriticised the leaders of those nations for failing to meet their existing climate finance commitments.

Writing in theFinancial Times in 2021, while also serving as the chair of the African Union, president Tshisekedi called for more support from developed countries:

“African forests and oceans serve as natural carbon sinks. It is time for Africa to be compensated – for the good of the continent and the planet.”

The DRC has alsosought international funding by sellingcarbon credits for planting or restoring forests.

The country’sNDC estimates that between 2021 and 2030, investment needs for cutting emissions would total $25.6bn and those for adapting to climate change another $23.1bn.

It notes that “given the numerous budgetary constraints to which the DRC is subject”, only around 2% of this money is likely to come from domestic funds. This leaves $47.7bn to be funded by international sources.

Between 2000 and 2020, the DRC received $2.7bn in “climate-related development finance”, according to theOrganisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). This is considerably less than other African nations that are far smaller, such as Uganda, and wealthier, such as South Africa.

The World Bank has been the largest provider of climate finance to the DRC. Other major contributors are Germany, the EU and the nation’s former coloniser, Belgium.

In recent years the DRC has had more success attracting finance specifically to support the protection of its rainforests.

At COP26, wealthy nationspledged “at least $1.5bn” between 2021 and 2025 to preserve Congo Basin forests, and donor countries have committed $500m through theCAFI.

However, the nation’sweak institutions have given rise toconcerns from donor countries about how money is being spent. CAFI’s first iteration, the Congo Basin Forest Fund (CBFF), was cancelled prematurely in 2014 due to apprehension about governance, which the UKdescribed as “inconsistent”.

Impacts and adaptation

The DRC has warmed by an average of 1.5C since the pre-industrial era – slightly higher than the global average of 1.3C, according to data fromBerkeley Earth.

As inmuch of Africa, weather stationsare sparse in the country, leading to reduced weather forecasting ability and uncertainty in trends.

The southern part of the country is prone to drought, while the region surrounding the Congo River floods seasonally.

The DRC’snational adaptation plan notes that several sectors of the country’s economy are “highly sensitive” to climate change, such as agriculture, forestry and energy.

One2010 study found “robust” declines in yields of several major crops – maize, sorghum, millet and groundnuts – across sub-Saharan Africa under changing temperature and rainfall regimes. Maize is the second-most important crop to the DRC, after cassava.

Anotherstudy, published in 2022, found that most of the DRC’s prime coffee-growing regions will become unsuitable for the crop by 2050 under a moderate-emissions scenario.

TheNotre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative’scountry index, which scores countries on their vulnerability and readiness to adapt to climate change, places the DRC in the top five countries most vulnerable countries in the world, with high vulnerability scores coupled with low readiness.

The country’s national adaptation plan provides some projections of future climate scenarios. Under a moderate emissions pathway, warming is expected to reach 1.4C above 1981-2010 levels by 2041-70 and 1.7C by 2071-2100.

The changes in rainfall are less clear, the document says, with some models projecting slight increases in average annual rainfall and some projecting slight decreases.

However, as the plan points out, this masks the geographical variation in rainfall patterns in the country – rainfall will likely continue to increase in some parts of the country and decrease in others.

During the rainy season, the Butembo-Beni Road washes out, leaving cars and trucks stranded for days at a time. Source: Global Press /Alamy Stock Photo

The plan also lays out priority areas for addressing vulnerability in the country, including the mainstreaming of climate change adaptation in national planning processes, strengtheningecosystem-based adaptation and taking gender into account during planning.

According to theWorld Meteorological Organization’sState of the Climate in Africa 2022 report, parts of the DRC received rainfall more than 200 millimetres (mm) above the 1951-2010 average in 2022. However, the southern part of the country received abnormally low rainfall that year – more than 350mm less than in an average year.

The water level inLake Tanganyika, which straddles the DRC’s eastern border with Tanzania, was raised by about 3.7 metres in April 2021 due to “torrential rains”, exposing nearby communities to “major flooding”, the report notes. More than 280,000 people were affected and 26,000 homes damaged across several flooding events.

Natural disasters – mostly floods, heavy rains and volcanic activity – caused more than 880,000 internal displacements in the DRC in 2021, according to records from theInternal Displacement Monitoring Centre. However, this number is dwarfed by the number of people displaced by conflict: 2.7 million people in 2021 alone.

At a US-Africa summit in Washington DC in December 2022, DRC president Tshisekedisaid that climate change was to blame for flooding that killed around 100 people in Kinshasa.

In May 2023,“catastrophic” flooding occurred around Lake Kivu, which sits on the DRC’s border with Rwanda. The DRC reported 460 deaths. Arapid attribution study of the flooding was unable to draw any conclusions as to the role of climate change in the flooding due to a lack of weather data. The authors wrote:

“We urgently need robust climate data and research in this highly vulnerable region. The scarcity and inaccessibility of meteorological data, as well as inadequate performance of climate models meant we couldn’t confidently evaluate the role of climate change in the rainfall that led to flooding. This limitation applies also to information on the impact, vulnerability, and exposure of people to heavy rainfall.”

Research has shown that African countries’ economic well-being is negatively impacted by climate change, withone 2015 study finding a reduction in gross domestic product growth by 0.67 percentage points for every 1C increase in 20-year average temperatures. The DRC is one of the countries in which that effect was most pronounced.

There is also concern that reduced rainfall under a future climate state will reduce the country’shydropower generation capacity; in 2017, low water levels in the Congo Riversparked fears of power shortages and downstream impacts on the DRC economy.

The DRC is also highly vulnerable to epidemics, with these disease outbreaks accounting for more than half of the natural hazards experienced in the country between 1980 and 2020, according to data compiled by theWorld Bank.

Over the past two decades, the country has faced outbreaks of more than half a dozen infectious and vector-borne diseases, according to theEmergency Events Database maintained by theUniversity of Louvain’sCentre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters.

Among the most common outbreaks registered by the database over that time are Ebola, measles, meningitis and cholera. A2022 study examining the relationships between disease and climate change found that 58% of known human pathogenic diseases – including the aforementioned ones – “have been at some point aggravated by climatic hazards”.

For example, the study says, malnutrition brought on by less-nutritious food can raise a population’s susceptibility to outbreaks, flooding can lead to an increase in breeding grounds for mosquitos and storms can damage critical infrastructure, reducing access to medical facilities or potable water.

Dr Jean Kaseya, director-general of theAfrica Centres for Disease Control and Prevention recently linked the cholera outbreak that afflicted more than a dozen countries across Africa over the past year to climate change,saying:

“Cholera in Africa is a climate change issue.”

According to the IPCC’s sixth assessment report on theimpacts of climate change, southern DRC will be one of the places in Africa worst-impacted by increased malaria prevalence by 2030.

The IPCC report also highlights the DRC as one of the countries most vulnerable to the effects of climate change on fisheries, due to the projected warming of its lakes and the reliance of the population on subsistence fishing.

Fishermen bringing in their catch on the shores of Lake Kivu at Goma. Credit: Kumar Sriskandan /Alamy Stock Photo.

The urban poor and smallholder farmers are particularly vulnerable sections of the population. A2021 report from UNICEF found that children in the DRC are the ninth-most vulnerable to climate and environmental impacts.

Combating climate change was one of the five pillars of the DRC’snational strategic development plan 2019-2023, which addressed the need for solutions for both adaptation and cutting emissions.

A2021 comment piece by several Congo Basin environment ministers and prominent scientists called for an investment of $150m in initiatives to “transform our understanding of these majestic forests, providing crucial input for policymakers to help them enact policies to avoid the region’s looming environmental crises”.

Notes

Graphic byJoe Goodman for Carbon Brief.

Data for energy consumption comes fromEnergy Institute Statistical Review of World Energy. Unlike earlier country profile infographics, exajoules (EJ) have been used instead of millions of tonnes of oil equivalent (Mtoe) as the unit of energy consumption.

Data for greenhouse gas emissions by sector and gas in the infographic is a combination of datasets.

The sectoral values for CO2 are from theEmissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR) database. “Other sectors” includes agriculture, industrial processes, waste and the production, transformation and refining of fuels.

Values for methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O) are taken from a dataset published inScientific Data byDr Matthew Jones of theUniversity of East Anglia, and collaborators. This dataset, in turn, obtains these values from thePRIMAP database. The figures for these gases cover all sectors, including land use, land-use change, and forestry (LULUCF). Values for F-gases are taken directly from thePRIMAP database.

The LULUCF label in the chart only covers CO2, which is by far the most significant greenhouse gas in this sector. These figures come from theJones et al. dataset, which obtains them from theGlobal Carbon Project. Note that there issignificant uncertainty around LULUCF emissions data, and other databases may have very different figures.

Per-capita emissions in 2023 are based on total emissions in theJones et al. dataset, and therefore do not include the minor contribution of F-gases. Population data is from theWorld Bank.

The ranking of the DRC as the 16th largest emitter in 2023 is also based on the Jones et al. dataset. It includes LULUCF emissions, and covers all greenhouse gases apart from F-gases.

The emissions figures in this article were updated in June 2025 to reflect changes in Carbon Brief’s methodology.