This chapter inlines all the API documentation into a singlelong book, suitable for printing or reading on a tablet.

(Top)

1 Terminology

2 Writing a Lint Check: Basics

2.1 Preliminaries

2.1.1 “Lint?”

2.1.2 API Stability

2.1.3 Kotlin

2.2 Concepts

2.3 Client API versus Detector API

2.4 Creating an Issue

2.5 TextFormat

2.6 Issue Implementation

2.7 Scopes

2.8 Registering the Issue

2.9 Implementing a Detector: Scanners

2.10 Detector Lifecycle

2.11 Scanner Order

2.12 Implementing a Detector: Services

2.13 Scanner Example

2.14 Analyzing Kotlin and Java Code

2.14.1 UAST

2.14.2 UAST Example

2.14.3 Looking up UAST

2.14.4 Resolving

2.14.5 Implicit Calls

2.14.6 PSI

2.15 Testing

3 Example: Sample Lint Check GitHub Project

3.1 Project Layout

3.2 :checks

3.3 lintVersion?

3.4 :library and :app

3.5 Lint Check Project Layout

3.6 Service Registration

3.7 IssueRegistry

3.8 Detector

3.9 Detector Test

4 AST Analysis

4.1 AST Analysis

4.2 UAST

4.3 UAST: The Java View

4.4 Expressions

4.5 UElement

4.6 Visiting

4.7 UElement to PSI Mapping

4.8 PSI to UElement

4.9 UAST versus PSI

4.10 Kotlin Analysis API

4.10.1 Nothing Type?

4.10.2 Compiled Metadata

4.10.3 Configuring lint to use K2

4.11 API Compatibility

4.12 Recipes

4.12.1 Resolve a function call

4.12.2 Resolve a variable reference

4.12.3 Get the containing class of a symbol

4.12.4 Get the fully qualified name of a class

4.12.5 Look up the deprecation status of a symbol

4.12.6 Look up visibility

4.12.7 Get the KtType of a class symbol

4.12.8 Resolve a KtType into a class

4.12.9 See if two types refer to the same raw class (erasure):

4.12.10 For an extension method, get the receiver type:

4.12.11 Get the PsiFile containing a symbol declaration

5 Publishing a Lint Check

5.1 Android

5.1.1 AAR Support

5.1.2 lintPublish Configuration

5.1.3 Local Checks

5.1.4 Unpublishing

6 Lint Check Unit Testing

6.1 Creating a Unit Test

6.2 Computing the Expected Output

6.3 Test Files

6.4 Trimming indents?

6.5 Dollars in Raw Strings

6.6 Quickfixes

6.7 Library Dependencies and Stubs

6.8 Binary and Compiled Source Files

6.9 Base64-encoded gzipped byte code

6.10 My Detector Isn't Invoked From a Test!

6.11 Language Level

7 Test Modes

7.1 How to debug

7.2 Handling Intentional Failures

7.3 Source-Modifying Test Modes

7.3.1 Fully Qualified Names

7.3.2 Import Aliasing

7.3.3 Type Aliasing

7.3.4 Parenthesis Mode

7.3.5 Argument Reordering

7.3.6 Body Removal

7.3.7 If to When Replacement

7.3.8 Whitespace Mode

7.3.9 CDATA Mode

7.3.10 Suppressible Mode

7.3.11 @JvmOverloads Test Mode

8 Adding Quick Fixes

8.1 Introduction

8.2 The LintFix builder class

8.3 Creating a LintFix

8.4 Available Fixes

8.5 Combining Fixes

8.6 Refactoring Java and Kotlin code

8.7 Regular Expressions and Back References

8.8 Emitting quick fix XML to apply on CI

9 Partial Analysis

9.1 About

9.2 The Problem

9.3 Overview

9.4 Does My Detector Need Work?

9.4.1 Catching Mistakes: Blocking Access to Main Project

9.4.2 Catching Mistakes: Simulated App Module

9.4.3 Catching Mistakes: Diffing Results

9.4.4 Catching Mistakes: Remaining Issues

9.5 Incidents

9.6 Constraints

9.7 Incident LintMaps

9.8 Module LintMaps

9.9 Optimizations

10 Data Flow Analyzer

10.1 Usage

10.2 Self-referencing Calls

10.3 Kotlin Scoping Functions

10.4 Limitations

10.5 Escaping Values

10.5.1 Returns

10.5.2 Parameters

10.5.3 Fields

10.6 Non Local Analysis

10.7 Examples

10.7.1 Simple Example

10.7.2 Complex Example

10.8 TargetMethodDataFlowAnalyzer

11 Annotations

11.1 Basics

11.2 Annotation Usage Types and isApplicableAnnotationUsage

11.2.1 Method Override

11.2.2 Method Return

11.2.3 Handling Usage Types

11.2.4 Usage Types Filtered By Default

11.2.5 Scopes

11.2.6 Inherited Annotations

12 Options

12.1 Usage

12.2 Creating Options

12.3 Reading Options

12.4 Specific Configurations

12.5 Files

12.6 Constraints

12.7 Testing Options

12.8 Supporting Lint 4.2, 7.0 and 7.1

13 Error Message Conventions

13.1 Length

13.2 Formatting

13.3 Punctuation

13.4 Include Details

13.5 Reference Android By Number

13.6 Keep Messages Stable

13.7 Plurals

13.8 Examples

14 Frequently Asked Questions

14.0.1 My detector callbacks aren't invoked

14.0.2 My lint check works from the unit test but not in the IDE

14.0.3 visitAnnotationUsage isn't called for annotations

14.0.4 How do I check if a UAST or PSI element is for Java or Kotlin?

14.0.5 What if I need aPsiElement and I have aUElement ?

14.0.6 How do I get theUMethod for aPsiMethod ?

14.0.7 How do get aJavaEvaluator?

14.0.8 How do I check whether an element is internal?

14.0.9 Is element inline, sealed, operator, infix, suspend, data?

14.0.10 How do I look up a class if I have its fully qualified name?

14.0.11 How do I look up a class if I have a PsiType?

14.0.12 How do I look up hierarchy annotations for an element?

14.0.13 How do I look up if a class is a subclass of another?

14.0.14 How do I know which parameter a call argument corresponds to?

14.0.15 How can my lint checks target two different versions of lint?

14.0.16 Can I make my lint check “not suppressible?”

14.0.17 Why are overloaded operators not handled?

14.0.18 How do I check out the current lint source code?

14.0.19 Where do I find examples of lint checks?

14.0.20 How do I analyze details about Kotlin?

15 Appendix: Recent Changes

16 Appendix: Environment Variables and System Properties

16.1 Environment Variables

16.1.1 Detector Configuration Variables

16.1.2 Lint Configuration Variables

16.1.3 Lint Development Variables

16.2 System Properties

Terminology

You don't need to read this up front and understand everything, butthis is hopefully a handy reference to return to.

In alphabetical order:

- Configuration

A configuration provides extra information or parameters to lint on a per-project, or even per-directory, basis. For example, the

lint.xmlfiles can change the severity for issues, or list incidents to ignore (matched for example by a regular expression), or even provide values for options read by a specific detector.- Context

An object passed into detectors in many APIs, providing data about (for example) which file is being analyzed (and in which project), and (for specific types of analysis) additional information; for example, an XmlContext points to the DOM document, a JavaContext includes the AST, and so on.

- Detector

The implementation of the lint check which registers Issues, analyzes the code, and reports Incidents.

- Implementation

An

Implementationtells lint how a given issue is actually analyzed, such as which detector class to instantiate, as well as which scopes the detector applies to.- Incident

A specific occurrence of the issue at a specific location. An example of an incident is:

Warning: In file IoUtils.kt, line 140, the field download folder is "/sdcard/downloads"; do not hardcode the path to `/sdcard`.- Issue

A type or class of problem that your lint check identifies. An issue has an associated severity (error, warning or info), a priority, a category, an explanation, and so on.

An example of an issue is “Don't hardcode paths to /sdcard”.

- IssueRegistry

An

IssueRegistryprovides a list of issues to lint. When you write one or more lint checks, you'll register these in anIssueRegistryand point to it using theMETA-INFservice loader mechanism.- LintClient

The

LintClientrepresents the specific tool the detector is running in. For example, when running in the IDE there is a LintClient which (when incidents are reported) will show highlights in the editor, whereas when lint is running as part of the Gradle plugin, incidents are instead accumulated into HTML (and XML and text) reports, and the build interrupted on error.- Location

A “location” refers to a place where an incident is reported. Typically this refers to a text range within a source file, but a location can also point to a binary file such as a

pngfile. Locations can also be linked together, along with descriptions. Therefore, if you for example are reporting a duplicate declaration, you can includeboth Locations, and in the IDE, both locations (if they're in the same file) will be highlighted. A location linked from another is called a “secondary” location, but the chaining can be as long as you want (and lint's unit testing infrastructure will make sure there are no cycles.)- Partial Analysis

A “map reduce” architecture in lint which makes it possible to analyze individual modules in isolation and then later filter and customize the partial results based on conditions outside of these modules. This is explained in greater detail in thepartial analysis chapter.

- Platform

The

Platformabstraction allows lint issues to indicate where they apply (such as “Android”, or “Server”, and so on). This means that an Android-specific check won't trigger warnings on non-Android code.- Scanner

A

Scanneris a particular interface a detector can implement to indicate that it supports a specific set of callbacks. For example, theXmlScannerinterface is where the methods for visiting XML elements and attributes are defined, and theClassScanneris where the ASM bytecode handling methods are defined, and so on.- Scope

Scopeis an enum which lists various types of files that a detector may want to analyze.For example, there is a scope for XML files, there is a scope for Java and Kotlin files, there is a scope for .class files, and so on.

Typically lint cares about whichset of scopes apply, so most of the APIs take an

EnumSet<Scope>, but we'll often refer to this as just “the scope” instead of the “scope set”.- Severity

For an issue, whether the incident should be an error, or just a warning, or neither (just an FYI highlight). There is also a special type of error severity, “fatal”, discussed later.

- TextFormat

An enum describing various text formats lint understands. Lint checks will typically only operate with the “raw” format, which is markdown-like (e.g. you can surround words with an asterisk to make it italics or two to make it bold, and so on).

- Vendor

A

Vendoris a simple data class which provides information about the provenance of a lint check: who wrote it, where to file issues, and so on.

Writing a Lint Check: Basics

Preliminaries

(If you already know a lot of the basics but you're here because you'verun into a problem and you're consulting the docs, take a look at thefrequently asked questions chapter.)

“Lint?”

Thelint tool shipped with the C compiler and provided additionalstatic analysis of C code beyond what the compiler checked.

Android Lint was named in honor of this tool, and with the Androidprefix to make it really clear that this is a static analysis toolintended for analysis of Android code, provided by the Android OpenSource Project — and to disambiguate it from the many other tools with“lint” in their names.

However, since then, Android Lint has broadened its support and is nolonger intended only for Android code. In fact, within Google, it isused to analyze all Java and Kotlin code. One of the reasons for thisis that it can easily analyze both Java and Kotlin code without havingto implement the checks twice. Additional features are described in thefeatures chapter.

We're planning to rename lint to reflect this new role, so we arelooking for good name suggestions.

API Stability

Lint's APIs are not stable, and a large part of Lint's API surface isnot under our control (such as UAST and PSI). Therefore, custom lintchecks may need to be updated periodically to keep working.

However, “some APIs are more stable than others”. In particular, thedetector API (described below) is much less likely to change than theclient API (which is not intended for lint check authors but for toolsintegrating lint to run within, such as IDEs and build systems).

However, this doesn't mean the detector API won't change. A large partof the API surface is external to lint; it's the AST libraries (PSI andUAST) for Java and Kotlin from JetBrains; it's the bytecode library(asm.ow2.io), it's the XML DOM library (org.w3c.dom), and so on. Lintintentionally stays up to date with these, so any API or behaviorchanges in these can affect your lint checks.

Lint's own APIs may also change. The current API has grown organicallyover the last 10 years (the first version of lint was released in 2011)and there are a number of things we'd clean up and do differently ifstarting over. Not to mention rename and clean up inconsistencies.

However, lint has been pretty widely adopted, so at this point creatinga nicer API would probably cause more harm than good, so we're limitingrecent changes to just the necessary ones. An example of this is thenewpartial analysis architecture in 7.0which is there to allow much better CI and incremental analysisperformance.

Kotlin

We recommend that you implement your checks in Kotlin. Part ofthe reason for that is that the lint API uses a number of Kotlinfeatures:

- Named and default parameters: Rather than using builders, some construction methods, like

Issue.create()have a lot of parameters with default parameters. The API is cleaner to use if you just specify what you need and rely on defaults for everything else. - Compatibility: We may add additional parameters over time. It isn't practical to add @JvmOverloads on everything.

- Package-level functions: Lint's API includes a number of package level utility functions (in previous versions of the API these are all thrown together in a

LintUtilsclass). - Deprecations: Kotlin has support for simple API migrations. For example, in the below example, the new

@Deprecatedannotation on lines 1 through 7 will be added in an upcoming release, to ease migration to a new API. IntelliJ can automatically quickfix these deprecation replacements.

@Deprecated("Use the new report(Incident) method instead, which is more future proof", ReplaceWith("report(Incident(issue, message, location, null, quickfixData))","com.android.tools.lint.detector.api.Incident" ))@JvmOverloadsopenfunreport( issue:Issue, location:Location, message:String, quickfixData:LintFix? =null) {// ...}As of 7.0, there is more Kotlin code in lint than remaining Javacode:

| Language | files | blank | comment | code |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kotlin | 420 | 14243 | 23239 | 130250 |

| Java | 289 | 8683 | 15205 | 101549 |

$ cloc lint/And that's for all of lint, including many old lint detectors whichhaven't been touched in years. In the Lint API library,lint/libs/lint-api, the code is 78% Kotlin and 22% Java.

Concepts

Lint will search your source code for problems. There are many types ofproblems, and each one is called anIssue, which has associatedmetadata like a unique id, a category, an explanation, and so on.

Each instance that it finds is called an “incident”.

The actual responsibility of searching for and reporting incidents ishandled by detectors — subclasses ofDetector. Your lint check willextendDetector, and when it has found a problem, it will “report”the incident to lint.

ADetector can analyze more than oneIssue. For example, thebuilt-inStringFormatDetector analyzes formatting strings passed toString.format() calls, and in the process of doing that discoversmultiple unrelated issues — invalid formatting strings, formattingstrings which should probably use the plurals API instead, mismatchedtypes, and so on. The detector could simply have a single issue called“StringFormatProblems” and report everything as a StringFormatProblem,but that's not a good idea. Each of these individual types of Stringformat problems should have their own explanation, their own category,their own severity, and most importantly should be individuallyconfigurable by the user such that they can disable or promote one ofthese issues separately from the others.

ADetector can indicate which sets of files it cares about. These arecalled “scopes”, and the way this works is that when you register yourIssue, you tell that issue whichDetector class is responsible foranalyzing it, as well as which scopes the detector cares about.

If for example a lint check wants to analyze Kotlin files, it caninclude theScope.JAVA_FILE scope, and now that detector will beincluded when lint processes Java or Kotin files.

Scope.JAVA_FILE may make it sound like there should also be aScope.KOTLIN_FILE. However,JAVA_FILE here really refers to both Java and Kotlin files since the analysis and APIs are identical for both (using “UAST”, a unified abstract syntax tree). However, at this point we don't want to rename it since it would break a lot of existing checks. We might introduce an alias and deprecate this one in the future.When detectors implement various callbacks, they can analyze thecode, and if they find a problematic pattern, they can “report”the incident. This means computing an error message, as well asa “location”. A “location” for an incident is really an errorrange — a file, and a starting offset and an ending offset. Locationscan also be linked together, so for example for a “duplicatedeclaration” error, you can and should include both locations.

Many detector methods will pass in aContext, or a more specificsubclass ofContext such asJavaContext orXmlContext. Thisallows lint to give the detectors information they may need, withoutpassing in a lot of parameters. It also allows lint to add additional dataover time without breaking signatures.

TheContext classes also provide many convenience APIs. For example,forXmlContext there are methods for creating locations for XML tags,XML attributes, just the name part of an XML attribute, and just thevalue part of an XML attribute. For aJavaContext there are alsomethods for creating locations, such as for a method call, includingwhether to include the receiver and/or the argument list.

When you report anIncident you can also provide aLintFix; this isa quickfix which the IDE can use to offer actions to take on thewarning. In some cases, you can offer a complete and correct fix (suchas removing an unused element). In other cases the fix may be lessclear; for example, theAccessibilityDetector asks you to set adescription for images; the quickfix will set the content attribute,but will leave the text value as TODO and will select the string suchthat the user can just type to replace it.

$name has already been declared”. This isn't just for cosmetics; it also makes lint'sbaseline mechanism work better since it currently matches by id + file + message, not by line numbers which typically drift over time.Client API versus Detector API

Lint's API has two halves:

- TheClient API: “Integrate (and run) lint from within a tool”. For example, both the IDE and the build system use this API to embed and invoke lint to analyze the code in the project or editor.

- TheDetector API: “Implement a new lint check”. This is the API which lets checkers analyze code and report problems that they find.

The class in the Client API which represents lint running in a tool iscalledLintClient. This class is responsible for, among other things:

- Reporting incidents found by detectors. For example, in the IDE, it will place error markers into the source editor, and in a build system, it may write warnings to the console or generate a report or even fail the build.

- Handling I/O. Detectors should never read files from disk directly. This allows lint checks to work smoothly in for example the IDE. When lint runs on the fly, and a lint check asks for the source file contents (or other supporting files), the

LintClientin the IDE will implement thereadFilemethod to first look in the open source editors and if the requested file is being edited, it will return the current (often unsaved!) contents. - Handling network traffic. Lint checks should never open URLConnections themselves. Instead, they should go through the lint API to request data for URLs. Among other things, this allows the

LintClientto use configured IDE proxy settings (as is done in the IntelliJ integration of lint). This is also good for testing, because the special unit test implementation of aLintClienthas a simple way to provide exact responses for specific URLs:

lint() .files(...) // Set up exactly the expected maven.google.com network output to // ensure stable version suggestions in the tests .networkData("https://maven.google.com/master-index.xml", "" + "<!--?xml version='1.0' encoding='UTF-8'?-->\n" + "<metadata>\n" + "<com.android.tools.build>" + "</com.android.tools.build></metadata>") .networkData("https://maven.google.com/com/android/tools/build/group-index.xml", "" + "<!--?xml version='1.0' encoding='UTF-8'?-->\n" + "<com.android.tools.build>\n" + "<gradleversions="\"2.3.3,3.0.0-alpha1\"/">\n" + "</gradle></com.android.tools.build>").run().expect(...)And much, much, more.However, most of the implementation ofLintClient is intended for integration of lint itself, and as a checkauthor you don't need to worry about it. The detector API will mattermore, and it's also less likely to change than the client API.

Also,

public such that lint's code in one package can access it from the other. There's normally a comment explaining that this is for internal use only, but be aware that even when something ispublic or notfinal, it might not be a good idea to call or override it.Creating an Issue

For information on how to set up the project and to actually publishyour lint checks, see thesample andpublishing chapters.

Issue is a final class, so unlikeDetector, you don't subclassit; you instantiate it viaIssue.create.

By convention, issues are registered inside the companion object of thecorresponding detector, but that is not required.

Here's an example:

classSdCardDetector :Detector(), SourceCodeScanner {companionobject Issues {@JvmFieldval ISSUE = Issue.create( id ="SdCardPath", briefDescription ="Hardcoded reference to `/sdcard`", explanation =""" Your code should not reference the `/sdcard` path directly; \ instead use `Environment.getExternalStorageDirectory().getPath()`. Similarly, do not reference the `/data/data/` path directly; it \ can vary in multi-user scenarios. Instead, use \ `Context.getFilesDir().getPath()`. """, moreInfo ="https://developer.android.com/training/data-storage#filesExternal", category = Category.CORRECTNESS, severity = Severity.WARNING, androidSpecific =true, implementation = Implementation( SdCardDetector::class.java, Scope.JAVA_FILE_SCOPE ) ) } ...There are a number of things to note here.

On line 4, we have theIssue.create() call. We store the issue into aproperty such that we can reference this issue both from theIssueRegistry, where we provide theIssue to lint, and also in theDetector code where we report incidents of the issue.

Note thatIssue.create is a method with a lot of parameters (and wewill probably add more parameters in the future). Therefore, it's agood practice to explicitly include the argument names (and thereforeto implement your code in Kotlin).

TheIssue provides metadata about a type of problem.

Theid is a short, unique identifier for this issue. Byconvention it is a combination of words, capitalized camel case (thoughyou can also add your own package prefix as in Java packages). Notethat the id is “user visible”; it is included in text output when lintruns in the build system, such as this:

src/main/kotlin/test/pkg/MyTest.kt:4: Warning: Do not hardcode "/sdcard/"; use Environment.getExternalStorageDirectory().getPath() instead [SdCardPath] val s: String = "/sdcard/mydir" -------------0 errors, 1 warnings(Notice the[SdCardPath] suffix at the end of the error message.)

The reason the id is made known to the user is that the ID is howthey'll configure and/or suppress issues. For example, to suppress thewarning in the current method, use

@Suppress("SdCardPath")(or in Java, @SuppressWarnings). Note that there is an IDE quickfix tosuppress an incident which will automatically add these annotations, soyou don't need to know the ID in order to be able to suppress anincident, but the ID will be visible in the annotation that itgenerates, so it should be reasonably specific.

Also, since the namespace is global, try to avoid picking generic namesthat could clash with others, or seem to cover a larger set of issuesthan intended. For example, “InvalidDeclaration” would be a poor idsince that can cover a lot of potential problems with declarationsacross a number of languages and technologies.

Next, we have thebriefDescription. You can think of this as a“category report header”; this is a static description for allincidents of this type, so it cannot include any specifics. This stringis used for example as a header in HTML reports for all incidents ofthis type, and in the IDE, if you open the Inspections UI, the variousissues are listed there using the brief descriptions.

Theexplanation is a multi line, ideally multi-paragraphexplanation of what the problem is. In some cases, the problem is selfevident, as in the case of “Unused declaration”, but in many cases, theissue is more subtle and might require additional explanation,particularly for what the developer shoulddo to address theproblem. The explanation is included both in HTML reports and in theIDE inspection results window.

Note that even though we're using a raw string, and even though thestring is indented to be flush with the rest of the issue registrationfor better readability, we don't need to calltrimIndent() onthe raw string. Lint does that automatically.

However, we do need to add line continuations — those are the trailing\'s at the end of the lines.

Note also that we have a Markdown-like simple syntax, described in the“TextFormat” section below. You can use asterisks for italics or doubleasterisks for bold, you can use apostrophes for code font, and so on.In terminal output this doesn't make a difference, but the IDE,explanations, incident error messages, etc, are all formatted usingthese styles.

Thecategory isn't super important; the main use is that categorynames can be treated as id's when it comes to issue configuration; forexample, a user can turn off all internationalization issues, or runlint against only the security related issues. The category is alsoused for locating related issues in HTML reports. If none of thebuilt-in categories are appropriate you can also create your own.

Theseverity property is very important. An issue can be either awarning or an error. These are treated differently in the IDE (whereerrors are red underlines and warnings are yellow highlights), and inthe build system (where errors can optionally break the build andwarnings do not). There are some other severities too; “fatal” is likeerror except these checks are designated important enough (and havevery few false positives) such that we run them during release builds,even if the user hasn't explicitly run a lint target. There's also“informational” severity, which is only used in one or two places, andfinally the “ignore” severity. This is never the severity you registerfor an issue, but it's part of the severities a developer can configurefor a particular issue, thereby turning off that particular check.

You can also specify amoreInfo URL which will be included in theissue explanation as a “More Info” link to open to read more detailsabout this issue or underlying problem.

TextFormat

All error messages and issue metadata strings in lint are interpretedusing simple Markdown-like syntax:

| Raw text format | Renders To |

|---|---|

| This is a `code symbol` | This is acode symbol |

This is*italics* | This isitalics |

This is**bold** | This isbold |

This is~~strikethrough~~ | This is |

| http://,https:// | http://,https:// |

\*not italics* | \*not italics* |

| ```language\n text\n``` | (preformatted text block) |

This is useful when error messages and issue explanations are shown inHTML reports generated by Lint, or in the IDE, where for example theerror message tooltips will use formatting.

In the API, there is aTextFormat enum which encapsulates thedifferent text formats, and the above syntax is referred to asTextFormat.RAW; it can be converted to.TEXT or.HTML forexample, which lint does when writing text reports to the console orHTML reports to files respectively. As a lint check author you don'tneed to know this (though you can for example with the unit testingsupport decide which format you want to compare against in yourexpected output), but the main point here is that your issue's briefdescription, issue explanation, incident report messages etc, shoulduse the above “raw” syntax. Especially the first conversion; errormessages often refer to class names and method names, and these shouldbe surrounded by apostrophes.

See theerror message chapter for more informationon how to craft error messages.

Issue Implementation

The last issue registration property is theimplementation. Thisis where we glue our metadata to our specific implementation of ananalyzer which can find instances of this issue.

Normally, theImplementation provides two things:

- The

.classfor ourDetectorwhich should be instantiated. In the code sample above it wasSdCardDetector. - The

Scopethat this issue's detector applies to. In the above example it wasScope.JAVA_FILE, which means it will apply to Java and Kotlin files.

Scopes

TheImplementation actually takes aset of scopes; we still referto this as a “scope”. Some lint checks want to analyze multiple typesof files. For example, theStringFormatDetector will analyze both theresource files declaring the formatting strings across various locales,as well as the Java and Kotlin files containingString.format callsreferencing the formatting strings.

There are a number of pre-defined sets of scopes in theScopeclass.Scope.JAVA_FILE_SCOPE is the most common, which is asingleton set containing exactlyScope.JAVA_FILE, but youcan always create your own, such as for example

EnumSet.of(Scope.CLASS_FILE,Scope.JAVA_LIBRARIES)When a lint issue requires multiple scopes, that means lint willonly run this detector ifall the scopes are available in therunning tool. When lint runs a full batch run (such as a Gradle linttarget or a full “Inspect Code” in the IDE), all scopes are available.

However, when lint runs on the fly in the editor, it only has access tothe current file; it won't re-analyzeall files in the project forevery few keystrokes. So in this case, the scope in the lint driveronly includes the current source file's type, and only lint checkswhich specify a scope that is a subset would run.

This is a common mistake for new lint check authors: the lint checkworks just fine as a unit test, but they don't see working in the IDEbecause the issue implementation requests multiple scopes, andallhave to be available.

Often, a lint check looks at multiple source file types to workcorrectly in all cases, but it can still identifysome problems givenindividual source files. In this case, theImplementation constructor(which takes a vararg of scope sets) can be handed additional sets ofscopes, called “analysis scopes”. If the current lint client's scopematches or is a subset of any of the analysis scopes, then the checkwill run after all.

Registering the Issue

Once you've created your issue, you need to provide it fromanIssueRegistry.

Here's an exampleIssueRegistry:

package com.example.lint.checksimport com.android.tools.lint.client.api.IssueRegistryimport com.android.tools.lint.client.api.Vendorimport com.android.tools.lint.detector.api.CURRENT_APIclassSampleIssueRegistry :IssueRegistry() {overrideval issues = listOf(SdCardDetector.ISSUE)overrideval api:Intget() = CURRENT_API// works with Studio 4.1 or later; see// com.android.tools.lint.detector.api.Api / ApiKtoverrideval minApi:Intget() =8// Requires lint API 30.0+; if you're still building for something// older, just remove this property.overrideval vendor: Vendor = Vendor( vendorName ="Android Open Source Project", feedbackUrl ="https://com.example.lint.blah.blah", contact ="author@com.example.lint" )}On line 8, we're returning our issue. It's a list, so anIssueRegistry can provide multiple issues.

Theapi property should be written exactly like the way itappears above in your own issue registry as well; this will recordwhich version of the lint API this issue registry was compiled against(because this references a static final constant which will be copiedinto the jar file instead of looked up dynamically when the jar isloaded).

TheminApi property records the oldest lint API level this checkhas been tested with.

Both of these are used at issue loading time to make sure lint checksare compatible, but in recent versions of lint (7.0) lint will moreaggressively try to load older detectors even if they have beencompiled against older APIs since there's a high likelihood that theywill work (it checks all the lint APIs in the bytecode and usesreflection to verify that they're still there).

Thevendor property is new as of 7.0, and gives lint authors away to indicate where the lint check came from. When users use lint,they're running hundreds and hundreds of checks, and sometimes it's notclear who to contact with requests or bug reports. When a vendor hasbeen specified, lint will include this information in error output andreports.

The last step towards making the lint check available is to maketheIssueRegistry known via the service loader mechanism.

Create a file named exactly

src/main/resources/META-INF/services/com.android.tools.lint.client.api.IssueRegistrywith the following contents (but where you substitute in your ownfully qualified class name for your issue registry):

com.example.lint.checks.SampleIssueRegistryIf you're not building your lint check using Gradle, you may not wantthesrc/main/resources prefix; the point is that your packaging ofthe jar file should containMETA-INF/services/ at the root of the jarfile.

Implementing a Detector: Scanners

We've finally come to the main task with writing a lint check:implementing theDetector.

Here's a trivial one:

classMyDetector :Detector() {overridefunrun(context:Context) { context.report(ISSUE, Location.create(context.file),"I complain a lot") }}This will just complain in every single file. Obviously, no real lintdetector does this; we want to do some analysis andconditionally reportincidents. For information about how to phrase error messages, see theerrormessage chapter.

In order to make it simpler to perform analysis, Lint has dedicatedsupport for analyzing various file types. The way this works is thatyou register interest, and then various callbacks will be invoked.

For example:

- When implementing

XmlScanner, in an XML element you can be called back- when any of a set of given tags are declared (

visitElement) - when any of a set of named attributes are declared (

visitAttribute) - and you can perform your own document traversal via

visitDocument

- when any of a set of given tags are declared (

- When implementing

SourceCodeScanner, in Kotlin and Java files you can be called back- when a method of a given name is invoked (

getApplicableMethodNamesandvisitMethodCall) - when a class of the given type is instantiated (

getApplicableConstructorTypesandvisitConstructor) - when a new class is declared which extends (possibly indirectly) a given class or interface (

applicableSuperClassesandvisitClass) - when annotated elements are referenced or combined (

applicableAnnotationsandvisitAnnotationUsage) - when any AST nodes of given types appear (

getApplicableUastTypesandcreateUastHandler)

- when a method of a given name is invoked (

- When implementing a

ClassScanner, in.classand.jarfiles you can be called back- when a method is invoked for a particular owner (

getApplicableCallOwnersandcheckCall - when a given bytecode instruction occurs (

getApplicableAsmNodeTypesandcheckInstruction) - like with XmlScanner's

visitDocument, you can perform your own ASM bytecode iteration viacheckClass

- when a method is invoked for a particular owner (

- There are various other scanners too, for example

GradleScannerwhich lets you visitbuild.gradleandbuild.gradle.ktsDSL closures,BinaryFileScannerwhich visits resource files such as webp and png files, andOtherFileScannerwhich lets you visit unknown files.

Detector already implements empty stub methods for all of these interfaces, so if you for example implementSourceFileScanner in your detector, you don't need to go and add empty implementations for all the methods you aren't using.super when you override methods; methods meant to be overridden are always empty so the super-call is superfluous.Detector Lifecycle

Detector registration is done by detector class, not by detectorinstance. Lint will instantiate detectors on your behalf. It willinstantiate the detector once per analysis, so you can stash state onthe detector in fields and accumulate information for analysis at theend.

There are some callbacks both before and after each individual file isanalyzed (beforeCheckFile andafterCheckFile), as well as before andafter analysis of all the modules (beforeCheckRootProject andafterCheckRootProject).

This is for example how the “unused resources” check works: we storeall the resource declarations and resource references we find in theproject as we process each file, and then in theafterCheckRootProject method we analyze the resource graph andcompute any resource declarations that are not reachable in thereference graph, and then we report each of these as unused.

Scanner Order

Some lint checks involve multiple scanners. This is pretty common inAndroid, where we want to cross check consistency between data inresource files with the code usages. For example, theString.formatcheck makes sure that the arguments passed toString.format match theformatting strings specified in all the translation XML files.

Lint defines an exact order in which it processes scanners, and withinscanners, data. This makes it possible to write some detectors moreeasily because you know that you'll encounter one type of data beforethe other; you don't have to handle the opposite order. For example, inourString.format example, we know that we'll always see theformatting strings before we see the code withString.format calls,so we can stash the formatting strings in a map, and when we processthe formatting calls in code, we can immediately issue reports; wedon't have to worry about encountering a formatting call for aformatting string we haven't processed yet.

Here's lint's defined order:

- Android Manifest

- Android resources XML files (alphabetical by folder type, so for example layouts are processed before value files like translations)

- Kotlin and Java files

- Bytecode (local

.classfiles and library.jarfiles) - TOML files

- Gradle files

- Other files

- ProGuard files

- Property Files

Similarly, lint will always process libraries before the modulesthat depend on them.

context.driver.requestRepeat(this, …). This is actually how the unused resource analysis works. Note however that this repeat is only valid within the current module; you can't re-run the analysis through the whole dependency graph.Implementing a Detector: Services

In addition to the scanners, lint provides a number of servicesto make implementation simpler. These include

ConstantEvaluator: Performs evaluation of AST expressions, so for example if we have the statementsx = 5; y = 2 * x, the constant evaluator can tell you that y is 10. This constant evaluator can also be more permissive than a compiler's strict constant evaluator; e.g. it can return concatenated strings where not all parts are known, or it can use non-final initial values of fields. This can help you findpossible bugs instead ofcertain bugs.TypeEvaluator: Attempts to provide the concrete type of an expression. For example, for the Java statementsObject s = new StringBuilder(); Object o = s, the type evaluator can tell you that the type ofoat this point is reallyStringBuilder.JavaEvaluator: Despite the unfortunate older name, this service applies to both Kotlin and Java, and can for example provide information about inheritance hierarchies, class lookup from fully qualified names, etc.DataFlowAnalyzer: Data flow analysis within a method.- For Android analysis, there are several other important services, like the

ResourceRepositoryand theResourceEvaluator. - Finally, there are a number of utility methods; for example there is an

editDistancemethod used to find likely typos.

Scanner Example

Let's create aDetector using one of the above scanners,XmlScanner, which will look at all the XML files in the project andif it encounters a<bitmap> tag it will report that<vector> shouldbe used instead:

import com.android.tools.lint.detector.api.Detectorimport com.android.tools.lint.detector.api.Detector.XmlScannerimport com.android.tools.lint.detector.api.Locationimport com.android.tools.lint.detector.api.XmlContextimport org.w3c.dom.ElementclassMyDetector :Detector(), XmlScanner {overridefungetApplicableElements() = listOf("bitmap")overridefunvisitElement(context:XmlContext, element:Element) {val incident = Incident(context, ISSUE) .message("Use `<vector>` instead of `<bitmap>`") .at(element) context.report(incident) }}The above is using the newIncident API from Lint 7.0 and on; inolder versions you can use the following API, which still works in 7.0:

classMyDetector :Detector(), XmlScanner {overridefungetApplicableElements() = listOf("bitmap")overridefunvisitElement(context:XmlContext, element:Element) { context.report(ISSUE, context.getLocation(element),"Use `<vector>` instead of `<bitmap>`") }}The second (older) form may seem simpler, but the new API allows a lotmore metadata to be attached to the report, such as an overrideseverity. You don't have to convert to the builder syntax to do this;you could also have written the second form as

context.report(Incident(ISSUE, context.getLocation(element),"Use `<vector>` instead of `<bitmap>`"))Analyzing Kotlin and Java Code

UAST

To analyze Kotlin and Java code, lint offers an abstract syntax tree,or “AST”, for the code.

This AST is called “UAST”, for “Universal Abstract Syntax Tree”, whichrepresents multiple languages in the same way, hiding the languagespecific details like whether there is a semicolon at the end of thestatements or whether the way an annotation class is declared is as@interface orannotation class, and so on.

This makes it possible to write a single analyzer which worksacross all languages supported by UAST. And this isvery useful; most lint checks are doing something API or data-flowspecific, not something language specific. If however you do need toimplement something very language specific, see the next section,“PSI”.

In UAST, each element is called aUElement, and there are anumber of subclasses —UFile for the compilation unit,UClass fora class,UMethod for a method,UExpression for an expression,UIfExpression for anif-expression, and so on.

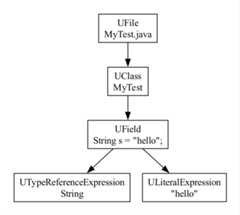

Here's a visualization of an AST in UAST for two equivalent programswritten in Kotlin and Java. These programs both result in the sameAST, shown on the right: aUFile compilation unit, containingaUClass namedMyTest, containingUField named s which hasan initializer setting the initial value tohello.

UProperty node which represents Kotlin properties. Instead, the AST will look the same as if the property had been implemented in Java: it will contain a private field and a public getter and a public setter (unless of course the Kotlin property specifies a private setter). If you’ve written code in Kotlin and have tried to access that Kotlin code from a Java file you will see the same thing — the “Java view” of Kotlin. The next section, “PSI”, will discuss how to do more language specific analysis.UAST Example

Here's an example (from the built-inAlarmDetector for Android) whichshows all of the above in practice; this is a lint check which makessure that if anyone callsAlarmManager.setRepeating, the secondargument is at least 5,000 and the third argument is at least 60,000.

Line 1 says we want to have line 3 called whenever lint comes across amethod tosetRepeating.

On lines 8-14 we make sure we're talking about the correct method on thecorrect class with the correct signature. This uses theJavaEvaluatorto check that the called method is a member of the named class. This isnecessary because the callback would also be invoked if lint cameacross a method call likeUnrelated.setRepeating; thevisitMethodCall callback only matches by name, not receiver.

On line 36 we use theConstantEvaluator to compute the value of eachargument passed in. This will let this lint check not only handle caseswhere you're specifying a specific value directly in the argument list,but also for example referencing a constant from elsewhere.

overridefungetApplicableMethodNames(): List<string> = listOf("setRepeating")overridefunvisitMethodCall( context:JavaContext, node:UCallExpression, method:PsiMethod) {val evaluator = context.evaluatorif (evaluator.isMemberInClass(method,"android.app.AlarmManager") && evaluator.getParameterCount(method) ==4 ) { ensureAtLeast(context, node,1,5000L) ensureAtLeast(context, node,2,60000L) }}privatefunensureAtLeast( context:JavaContext, node:UCallExpression, parameter:Int, min:Long) {val argument = node.valueArguments[parameter]val value = getLongValue(context, argument)if (value < min) {val message ="Value will be forced up to$min as of Android 5.1; " +"don't rely on this to be exact" context.report(ISSUE, argument, context.getLocation(argument), message) }}privatefungetLongValue( context:JavaContext, argument:UExpression):Long {val value = ConstantEvaluator.evaluate(context, argument)if (valueis Number) {return value.toLong() }return java.lang.Long.MAX_VALUE}Looking up UAST

To write your detector's analysis, you need to know what the AST foryour code of interest looks like. Instead of trying to figure it out byexamining the elements under a debugger, a simple way to find out is to“pretty print” it, using theUElement extension methodasRecursiveLogString.

For example, given the following unit test:

lint().files( kotlin(""+"package test.pkg\n"+"\n"+"class MyTest {\n"+" val s: String =\"hello\"\n"+"}\n"),...If you evaluatecontext.uastFile?.asRecursiveLogString() fromone of the callbacks, it will print this:

UFile (package = test.pkg) UClass (name = MyTest) UField (name = s) UAnnotation (fqName = org.jetbrains.annotations.NotNull) ULiteralExpression (value = "hello") UAnnotationMethod (name = getS) UAnnotationMethod (name = MyTest)(This also illustrates the earlier point about UAST representing theJava view of the code; here the read-only public Kotlin property “s” isrepresented by both a private fields and a public getter method,getS().)

Resolving

When you have a method call, or a field reference, you may want to takea look at the called method or field. This is called “resolving”, andUAST supports it directly; on aUCallExpression for example, call.resolve(), which returns aPsiMethod, which is like aUMethod,but may not represent a method we have source for (which for examplewould be the case if you resolve a reference to the JDK or to a librarywe do not have sources for). You can call.toUElement() on thePSI element to try to convert it to UAST if source is available.

Implicit Calls

Kotlin supports operator overloading for a number of built-inoperators. For example, if you have the following code,

funtest(n1:BigDecimal, n2:BigDecimal) {// Here, this is really an infix call to BigDecimal#compareToif (n1 < n2) { ... }}the< here is actually a function call (which you can verify byinvoking Go To Declaration over the symbol in the IDE). This is notsomething that is built specially for theBigDecimal class; thisworks on any of your Java classes as well, and Kotlin if you put theoperator modifier as part of the function declaration.

However, note that in the abstract syntax tree, this isnotrepresented as aUCallExpression; here we'll have aUBinaryExpression with left operandn1, right operandn2 andoperatorUastBinaryOperator.LESS. This means that if your lint checkis specifically looking atcompareTo calls, you can't just visiteveryUCallExpression; youalso have to visit everyUBinaryExpression, and check whether it's invoking acompareTomethod.

This is not just specific to binary operators; it also applies to unaryoperators (such as!,-,++, and so on), as well as even arrayaccesses; an array access can map to aget call or aset calldepending on how it's used.

Lint has some special support to help handle these situations.

First, the built-in support for call callbacks (where you register aninterest in call names by returning names from thegetApplicableMethodNames and then responding in thevisitMethodCallcallback) already handles this automatically. If you register forexample an interest in method calls tocompareTo, it will invoke yourcallback for the binary operator scenario shown above as well, passingyou a call which has the right value arguments, method name, and so on.

The way this works is that lint can create a “wrapper” class whichpresents the underlyingUBinaryExpression (orUArrayAccessExpression and so on) as aUCallExpression. In the caseof a binary operator, the value parameter list will be the left andright operands. This means that your code can just process this as ifthe code had written as an explicit call instead of using the operatorsyntax. You can also directly look for this wrapper class,UImplicitCallExpression, which has an accessor method for looking upthe original or underlying element. And you can construct thesewrappers yourself, viaUBinaryExpression.asCall(),UUnaryExpression.asCall(), andUArrayAccessExpression.asCall().

There is also a visitor you can use to visit all calls —UastCallVisitor, which will visit all calls, including those fromarray accesses and unary operators and binary operators.

This support is particularly useful for array accesses, since unlikethe operator expression, there is noresolveOperator method onUArrayExpression. There is an open request for that in the UAST issuetracker (KTIJ-18765), but for now, lint has a workaround to handle theresolve on its own.

PSI

PSI is short for “Program Structure Interface”, and is IntelliJ's ASTabstraction used for all language modeling in the IDE.

Note that there is adifferent PSI representation for eachlanguage. Java and Kotlin have completely different PSI classesinvolved. This means that writing a lint check using PSI would involvewriting a lot of logic twice; once for Java, and once for Kotlin. (Andthe Kotlin PSI is a bit trickier to work with.)

That's what UAST is for: there's a “bridge” from the Java PSI to UASTand there's a bridge from the Kotlin PSI to UAST, and your lint checkjust analyzes UAST.

However, there are a few scenarios where we have to use PSI.

The first, and most common one, is listed in the previous section onresolving. UAST does not completely replace PSI; in fact, PSI leaksthrough in part of the UAST API surface. For example,UMethod.resolve() returns aPsiMethod. And more importantly,UMethodextendsPsiMethod.

PsiMethod and other PSI classes contain some unfortunate APIs that only work for Java, such as asking for the method body. BecauseUMethod extendsPsiMethod, you might be tempted to callgetBody() on it, but this will return null from Kotlin. If your unit tests for your lint check only have test cases written in Java, you may not realize that your check is doing the wrong thing and won't work on Kotlin code. It should calluastBody on theUMethod instead. Lint's special detector for lint detectors looks for this and a few other scenarios (such as callingparent instead ofuastParent), so be sure to configure it for your project.When you are dealing with “signatures” — looking at classes andclass inheritance, methods, parameters and so on — using PSI isfine — and unavoidable since UAST does not represent bytecode(though in the future it potentially could, via a decompiler)or any other JVM languages than Kotlin and Java.

However, if you are looking at anythinginside a method or classor field initializer, youmust use UAST.

Thesecond scenario where you may need to use PSI is where you haveto do something language specific which is not represented in UAST. Forexample, if you are trying to look up the names or default values of aparameter, or whether a given class is a companion object, then you'llneed to dip into Kotlin PSI.

There is usually no need to look at Java PSI since UAST fully coversit, unless you want to look at individual details like specificwhitespace between AST nodes, which is represented in PSI but not UAST.

Testing

Writing unit tests for the lint check is important, and this is coveredin detail in the dedicatedunit testingchapter.

Example: Sample Lint Check GitHub Project

Thehttps://github.com/googlesamples/android-custom-lint-rulesGitHub project provides a sample lint check which shows a workingskeleton.

This chapter walks through that sample project and explainswhat and why.

Project Layout

Here's the project layout of the sample project:

We have an application module,app, which depends (via animplementation dependency) on alibrary, and the library itself hasalintPublish dependency on thechecks project.

:checks

Thechecks project is where the actual lint checks are implemented.This project is a plain Kotlin or plain Java Gradle project:

apply plugin:'java-library'apply plugin:'kotlin'apply plugin: 'com.android.lint'. This pulls in the standalone Lint Gradle plugin, which adds a lint target to this Kotlin project. This means that you can run./gradlew lint on the:checks project too. This is useful because lint ships with a dozen lint checks that look for mistakes in lint detectors! This includes warnings about using the wrong UAST methods, invalid id formats, words in messages which look like code which should probably be surrounded by apostrophes, etc.The Gradle file also declares the dependencies on lint APIsthat our detector needs:

dependencies { compileOnly"com.android.tools.lint:lint-api:$lintVersion" compileOnly"com.android.tools.lint:lint-checks:$lintVersion" testImplementation"com.android.tools.lint:lint-tests:$lintVersion"}The second dependency is usually not necessary; you just need to dependon the Lint API. However, the built-in checks define a lot ofadditional infrastructure which it's sometimes convenient to depend on,such asApiLookup which lets you look up the required API level for agiven method, and so on. Don't add the dependency until you need it.

lintVersion?

What is thelintVersion variable defined above?

Here's the top level build.gradle

buildscript { ext { kotlinVersion ='1.4.32'// Current lint target: Studio 4.2 / AGP 7//gradlePluginVersion = '4.2.0-beta06'//lintVersion = '27.2.0-beta06'// Upcoming lint target: Arctic Fox / AGP 7 gradlePluginVersion ='7.0.0-alpha10' lintVersion ='30.0.0-alpha10' } repositories { google() mavenCentral() } dependencies { classpath"com.android.tools.build:gradle:$gradlePluginVersion" classpath"org.jetbrains.kotlin:kotlin-gradle-plugin:$kotlinVersion" }}The$lintVersion variable is defined on line 11. We don't technicallyneed to define the$gradlePluginVersion here or add it to the classpath on line 19, but that's done so that we can add thelintplugin on the checks themselves, as well as for the other modules,:app and:library, which do need it.

When you build lint checks, you're compiling against the Lint APIsdistributed on maven.google.com (which is referenced viagoogle() inGradle files). These follow the Gradle plugin version numbers.

Therefore, you first pick which of lint's API you'd like to compileagainst. You should use the latest available if possible.

Once you know the Gradle plugin version number, say 4.2.0-beta06, youcan compute the lint version number by simply adding23 to themajor version of the gradle plugin, and leave everything the same:

lintVersion = gradlePluginVersion + 23.0.0

For example, 7 + 23 = 30, so AGP version7.something corresponds toLint version30.something. As another example; as of this writing thecurrent stable version of AGP is 4.1.2, so the corresponding version ofthe Lint API is 27.1.2.

:library and :app

Thelibrary project depends on the lint check project, and willpackage the lint checks as part of its payload. Theapp projectthen depends on thelibrary, and has some code which triggersthe lint check. This is there to demonstrate how lint checks canbe published and consumed, and this is described in detail in thePublishing a Lint Check chapter.

Lint Check Project Layout

The lint checks source project is very simple

checks/build.gradlechecks/src/main/resources/META-INF/services/com.android.tools.lint.client.api.IssueRegistrychecks/src/main/java/com/example/lint/checks/SampleIssueRegistry.ktchecks/src/main/java/com/example/lint/checks/SampleCodeDetector.ktchecks/src/test/java/com/example/lint/checks/SampleCodeDetectorTest.ktFirst is the build file, which we've discussed above.

Service Registration

Then there's the service registration file. Notice how this file is inthe source setsrc/main/resources/, which means that Gradle willtreat it as a resource and will package it into the output jar, in theMETA-INF/services folder. This is using the service-provider loading facility in the JDK to register a service lint can look up. Thekey is the fully qualified name for lint'sIssueRegistry class.And thecontents of that file is a single line, the fullyqualified name of the issue registry:

$cat checks/src/main/resources/META-INF/services/com.android.tools.lint.client.api.IssueRegistrycom.example.lint.checks.SampleIssueRegistry(The service loader mechanism is understood by IntelliJ, so it willcorrectly update the service file contents if the issue registry isrenamed etc.)

The service registration can contain more than one issue registry,though there's usually no good reason for that, since a single issueregistry can provide multiple issues.

IssueRegistry

Next we have theIssueRegistry linked from the service registration.Lint will instantiate this class and ask it to provide a list ofissues. These are then merged with lint's other issues when lintperforms its analysis.

In its simplest form we'd only need to have the following codein that file:

package com.example.lint.checksimport com.android.tools.lint.client.api.IssueRegistryclassSampleIssueRegistry :IssueRegistry() { override val issues = listOf(SampleCodeDetector.ISSUE)}However, we're also providing some additional metadata about these lintchecks, such as theVendor, which contains information about theauthor and (optionally) contact address or bug tracker information,displayed to users when an incident is found.

We also provide some information about which version of lint's API thecheck was compiled against, and the lowest version of the lint API thatthis lint check has been tested with. (Note that the API versions arenot identical to the versions of lint itself; the idea and hope is thatthe API may evolve at a slower pace than updates to lint delivering newfunctionality).

Detector

TheIssueRegistry references theSampleCodeDetector.ISSUE,so let's take a look atSampleCodeDetector:

classSampleCodeDetector :Detector(), UastScanner {// ...companionobject {/** * Issue describing the problem and pointing to the detector * implementation. */@JvmFieldval ISSUE: Issue = Issue.create(// ID: used in @SuppressLint warnings etc id ="SampleId",// Title -- shown in the IDE's preference dialog, as category headers in the// Analysis results window, etc briefDescription ="Lint Mentions",// Full explanation of the issue; you can use some markdown markup such as// `monospace`, *italic*, and **bold**. explanation =""" This check highlights string literals in code which mentions the word `lint`. \ Blah blah blah. Another paragraph here. """, category = Category.CORRECTNESS, priority =6, severity = Severity.WARNING, implementation = Implementation( SampleCodeDetector::class.java, Scope.JAVA_FILE_SCOPE ) ) }}TheIssue registration is pretty self-explanatory, and the detailsabout issue registration are covered in thebasicschapter. The excessive comments here are there to explain the sample,and there are usually no comments in issue registration code like this.

Note how on line 29, theIssue registration names theDetectorclass responsible for analyzing this issue:SampleCodeDetector. Inthe above I deleted the body of that class; here it is now without theissue registration at the end:

package com.example.lint.checksimport com.android.tools.lint.client.api.UElementHandlerimport com.android.tools.lint.detector.api.Categoryimport com.android.tools.lint.detector.api.Detectorimport com.android.tools.lint.detector.api.Detector.UastScannerimport com.android.tools.lint.detector.api.Implementationimport com.android.tools.lint.detector.api.Issueimport com.android.tools.lint.detector.api.JavaContextimport com.android.tools.lint.detector.api.Scopeimport com.android.tools.lint.detector.api.Severityimport org.jetbrains.uast.UElementimport org.jetbrains.uast.ULiteralExpressionimport org.jetbrains.uast.evaluateStringclassSampleCodeDetector :Detector(), UastScanner {overridefungetApplicableUastTypes(): List<class<out uelement?="">> {return listOf(ULiteralExpression::class.java) }overridefuncreateUastHandler(context:JavaContext): UElementHandler {returnobject : UElementHandler() {overridefunvisitLiteralExpression(node:ULiteralExpression) {val string = node.evaluateString() ?:returnif (string.contains("lint") && string.matches(Regex(".*\\blint\\b.*"))) { context.report( ISSUE, node, context.getLocation(node),"This code mentions `lint`: **Congratulations**" ) } } } }}This lint check is very simple; for Kotlin and Java files, it visitsall the literal strings, and if the string contains the word “lint”,then it issues a warning.

This is using a very general mechanism of AST analysis; specifying therelevant node types (literal expressions, on line 18) and visiting themon line 23. Lint has a large number of convenience APIs for doinghigher level things, such as “call this callback when somebody extendsthis class”, or “when somebody calls a method namedfoo”, and so on.Explore theSourceCodeScanner and otherDetector interfaces to seewhat's possible. We'll hopefully also add more dedicated documentationfor this.

Detector Test

Last but not least, let's not forget the unit test:

package com.example.lint.checksimport com.android.tools.lint.checks.infrastructure.TestFiles.javaimport com.android.tools.lint.checks.infrastructure.TestLintTask.lintimport org.junit.TestclassSampleCodeDetectorTest {@TestfuntestBasic() { lint().files( java(""" package test.pkg; public class TestClass1 { // In a comment, mentioning "lint" has no effect private static String s1 = "Ignore non-word usages: linting"; private static String s2 = "Let's say it: lint"; } """ ).indented() ) .issues(SampleCodeDetector.ISSUE) .run() .expect(""" src/test/pkg/TestClass1.java:5: Warning: This code mentions lint: Congratulations [SampleId] private static String s2 = "Let's say it: lint"; ∼∼∼∼∼∼∼∼∼∼∼∼∼∼∼∼∼∼∼∼ 0 errors, 1 warnings """ ) }}As you can see, writing a lint unit test is very simple, becauselint ships with a dedicated testing library; this is what the

testImplementation"com.android.tools.lint:lint-tests:$lintVersion"dependency in build.gradle pulled in.

Unit testing lint checks is covered in depth in theunittesting chapter, so we'll cut theexplanation of the above test short here.

AST Analysis

To analyze Kotlin and Java files, lint offers many convenience callbacksto make it simple to accomplish common tasks:

- Check calls to a particular method name

- Instantiating a particular class

- Extending a particular super class or interface

- Using a particular annotation, or calling an annotated method

And more. See theSourceCodeScanner interface for more information.

It also has various helpers, such as aConstantEvaluator and aDataFlowAnalyzer to help analyze code.

But in some cases, you'll need to dig in and analyze the “AST” yourself.

AST Analysis

AST is short for “Abstract Syntax Tree” — a tree representation of thesource code. Consider the following very simple Java program:

// MyTest.javapackage test.pkg;publicclassMyTest {Strings="hello";}Here's the AST for the above program, the way it's representedinternally in IntelliJ.

This is actually a simplified view; in reality, there are alsowhitespace nodes tracking all the spans of whitespace characters betweenthese nodes.

Anyway, you can see there is quite a bit of detail here — trackingthings like the keywords, the variables, references to for example thepackage — and higher level concepts like a class and a field, which I'vemarked with a thicker border.

Here's the corresponding Kotlin program:

// MyTest.ktpackage test.pkgclassMyTest {val s: String ="hello"}And here's the corresponding AST in IntelliJ:

This program is equivalent to the Java one.But notice that it has a completely different shape! They referencedifferent element classes,PsiClass versusKtClass, and on and onall the way down.

But there's some commonality — they each have a node for the file, forthe class, for the field, and for the initial value, the string.

UAST

We can construct a new AST that represents the same concepts:

This is a unified AST, in something called “UAST”, short for UnifiedAbstract Syntax Tree. UAST is the primary AST representation we use forcode in Lint. All the node classes here are prefixed with a capital U,for UAST. And this is the UAST for the first Java file example above.

Here's the UAST for the corresponding Kotlin example:

As you can see, the ASTs are not always identical. For Strings, inKotlin, we often end up with an extra parentUInjectionHost. But forour purposes, you can see that the ASTs are mostly the same, so if youhandle the Kotlin scenario, you'll handle the Java ones too.

UAST: The Java View

Note that “Unified” in the name here is a bit misleading. From the nameyou may assume that this is some sort of superset of the ASTs acrosslanguages — an AST that can represent everything needed by alllanguages. But that's not the case! Instead, a better way to think of itis as theJava view of the AST.

If you for example have the following Kotlin data class:

dataclassPerson(var id: String,var name: String)This is a Kotlin data class with two properties. So you might expectthat UAST would have a way to represent these concepts. This shouldbe aUDataClass with twoUProperty children, right?

But Java doesn't support properties. If you try to access aPersoninstance from Java, you'll notice that it exposes a number of publicmethods that you don't see there in the Kotlin code — in addition togetId,setId,getName andsetName, there's alsocomponent1 andcomponent2 (for destructuring), andcopy.

These methods are directly callable from Java, so they show up in UAST,and your analysis can reason about them.

Consider another complete Kotlin source file,test.kt:

var property =0Here's the UAST representation:

Here we have a very simple Kotlin file — for a single Kotlin property.But notice at the UAST level, there's no such thing as top level methodsand properties. In Java, everything is a class, sokotlinc will createa “facade class”, using the filename plus “Kt”. So we see ourTestKtclass. And there are three members here. There's the getter and thesetter for this property, asgetProperty andsetProperty. And thenthere is the private field itself, where the property is stored.

This all shows up in UAST. It's the Java view of the Kotlin code. Thismay seem limiting, but in practice, for most lint checks, this isactually what you want. This makes it easy to reason about calls to APIsand so on.

Expressions

You may be getting the impression that the UAST tree is very shallow andonly represents high level declarations, like files, classes, methodsand properties.

That's not the case. While itdoes skip low-level, language-specificdetails things like whitespace nodes and individual keyword nodes, allthe various expression types are represented and can be reasoned about.Take the following expression:

if (s.length >3)0else s.count { it.isUpperCase() }This maps to the following UAST tree:

As you can see it's modeling the if, the comparison, the lambda, and soon.

UElement

Every node in UAST is a subclass of aUElement. There's a parentpointer, which is handy for navigating around in the AST.

The real skill you need for writing lint checks is understanding theAST, and then doing pattern matching on it. And a simple trick for thisis to create the Kotlin or Java code you want, in a unit test, and thenin your detector, recursively print out the UAST as a tree.

Or in the debugger, anytime you have aUElement, you can callUElement.asRecursiveLogString on it, evaluate and see what you find.

For example, for the following Kotlin code:

import java.util.Datefuntest() {val warn1 = Date()val ok = Date(0L)}here's the corresponding UASTasRecursiveLogString output:

UFile (package = ) UImportStatement (isOnDemand = false) UClass (name = JavaTest) UMethod (name = test) UBlockExpression UDeclarationsExpression ULocalVariable (name = warn1) UCallExpression (kind = UastCallKind(name='constructor_call'), … USimpleNameReferenceExpression (identifier = Date) UDeclarationsExpression ULocalVariable (name = ok) UCallExpression (kind = UastCallKind(name='constructor_call'), … USimpleNameReferenceExpression (identifier = Date) ULiteralExpression (value = 0)Visiting

You generally shouldn't visit a source file on your own. Lint has aspecialUElementHandler for that, which is used to ensure we don'trepeat visiting a source file thousands of times, one per detector.

But when you're doing local analysis, you sometimes need to visit asubtree.

To do that, just extendAbstractUastVisitor and pass the visitor totheaccept method of the correspondingUElement.

method.accept(object : AbstractUastVisitor() {overridefunvisitSimpleNameReferenceExpression(node:USimpleNameReferenceExpression):Boolean {// your code herereturnsuper.visitSimpleNameReferenceExpression(node) }})In a visitor, you generally want to callsuper as shown above. You canalsoreturn true if you've “seen enough” and can stop visiting theremainder of the AST.

If you're visiting Java PSI elements, you use aJavaRecursiveElementVisitor, and in Kotlin PSI, use aKtTreeVisitor.

UElement to PSI Mapping

UAST is built on top of PSI, and eachUElement has asourcePsiproperty (which may be null). This lets you map from the general UASTnode, down to the specific PSI elements.

Here's an illustration of that:

We have our UAST tree in the top right corner. And here's the Java PSIAST behind the scenes. We can access the underlying PSI node for aUElement by accessing thesourcePsi property. So when you do need to dipinto something language specific, that's trivial to do.

Note that in some cases, these references are null.

MostUElement nodes point back to the PSI AST - whether a JavaAST or a Kotlin AST. Here's the same AST, but with thetype of thesourcePsi property for each node added.

You can see that the facade class generated to contain the top levelfunctions has a nullsourcePsi, because in theKotlin PSI, there is no realKtClass for a facade class. And for thethree members, the private field and the getter and the setter, they allcorrespond to the exact same, singleKtProperty instance, the singlenode in the Kotlin PSI that these methods were generated from.

PSI to UElement

In some cases, we can also map back to UAST from PSI elements, using thetoUElement extension function.

For example, let's say we resolve a method call. This returns aPsiMethod, not aUMethod. But we can get the correspondingUMethodusing the following:

val resolved = call.resolve() ?:returnval uDeclaration = resolve.toUElement()Note however thattoUElement may return null. For example, if you'veresolved to a method call that is compiled (which you can check usingresolved is PsiCompiledElement), UAST cannot convert it.

UAST versus PSI

UAST is the preferred AST to use when you're writing lint checks forKotlin and Java. It lets you reason about things that are the sameacross the languages. Declarations. Function calls. Super classes.Assignments. If expressions. Return statements. And on and on.

Thereare lint checks that are language specific — for example, ifyou write a lint check that forbids the use of companion objects — inthat case, there's no big advantage to using UAST over PSI; it's onlyever going to run on Kotlin code. (Note however that lint's APIs andconvenience callbacks are all targeting UAST, so it's easier to writeUAST lint checks even for the language-specific checks.)

The vast majority of lint checks however aren't language specific,they'reAPI or bug pattern specific. And if the API can be calledfrom Java, you want your lint check to not only flag problems in Kotlin,but in Java code as well. You don't want to have to write the lint checktwice — so if you use UAST, a single lint check can work for both. Butwhile you generally want to use UAST for your analysis (and lint's APIsare generally oriented around UAST), thereare cases where it'sappropriate to dip into PSI.

In particular, you should use PSI when you're doing something highlylanguage specific, and where the language details aren't exposed in UAST.

For example, let's say you need to determine if aUClass is a Kotlin“companion object”. You could cheat and look at the class name to see ifit's “Companion”. But that's not quite right; in Kotlin you canspecify a custom companion object name, and of course users are freeto create classes named “Companion” that aren't companion objects:

classTest {companionobject MyName {// Companion object not named "Companion"! }object Companion {// Named "Companion" but not a companion object! }}The right way to do this is using Kotlin PSI, via theUElement.sourcePsi property:

// Skip companion objectsval source = node.sourcePsiif (sourceis KtObjectDeclaration && source.isCompanion()) {return}(To figure out how to write the above code, use a debugger on a testcase and look at theUClass.sourcePsi property; you'll discover thatit's some subclass ofKtObjectDeclaration; look up its most generalsuper interface or class, and then use code completion to discoveravailable APIs, such asisCompanion().)

Kotlin Analysis API

Using Kotlin PSI was the state of the art for correctly analyzing Kotlincode until recently. But when you look at the PSI, you'll discover thatsome things are really hard to accomplish — in particular, resolvingreference, and dealing with Kotlin types.

Lint doesn't actually give you access to everything you need if you wantto try to look up types in Kotlin PSI; you need something called the“binding context”, which is not exposed anywhere! And this omission isdeliberate, because this is an implementation detail of the oldcompiler. The future is K2; a complete rewrite of the compiler frontend, which is no longer using the old binding context. And as part ofthe tooling support for K2, there's a new API called the “KotlinAnalysis API” you can use to dig into details about Kotlin.

For most lint checks, you should just use UAST if you can. But when youneed to know reallydetailed Kotlin information, especially aroundtypes, and smart casts, and null inference, and so on, the KotlinAnalysis API is your best friend (and only option...)

KtAnalysisSession returned byanalyze, has been renamedKaSession. Most APIs now have the prefixKa.Nothing Type?

Here's a simple example:

funtestTodo() {if (SDK_INT <11) { TODO()// never returns }val actionBar = getActionBar()// OK - SDK_INT must be >= 11 !}Here we have a scenario where we know that the TODO call will neverreturn, and lint can take advantage of that when analyzing the controlflow — in particular, it should understand that after the TODO() callthere's no chance of fallthrough, so it can conclude that SDK_INT mustbe at least 11 after the if block.

The way the Kotlin compiler can reason about this is that theTODOmethod in the standard library has a return type ofNothing.

@kotlin.internal.InlineOnlypublicinlinefunTODO():Nothing =throw NotImplementedError()TheNothing return type means it will never return.

Before the Kotlin lint analysis API, lint didn't have a way to reasonabout theNothing type. UAST only returns Java types, which maps tovoid. So instead, lint had an ugly hack that just hardcoded well knownnames of methods that don't return:

if (nextStatementis UCallExpression) {val methodName = nextStatement.methodNameif (methodName =="fail" || methodName =="error" || methodName =="TODO") {returntrue }However, with the Kotlin analysis API, this is easy:

funcallNeverReturns(call:UCallExpression):Boolean {val sourcePsi = call.sourcePsias? KtCallExpression ?:returnfalse analyze(sourcePsi) {val callInfo = sourcePsi.resolveToCall() ?:returnfalseval returnType = callInfo.singleFunctionCallOrNull()?.symbol?.returnTypereturn returnType !=null && returnType.isNothingType }}Older APIs (pre-8.7.0-alpha04):