| Geodesy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Fundamentals | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Standards (history)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ingeodesy, thefigure of the Earth is the size and shape used to model planetEarth. The kind offigure depends on application, including the precision needed for the model. Aspherical Earth is a well-known historical approximation that is satisfactory forgeography,astronomy and many other purposes. Several models with greater accuracy (includingellipsoid) have been developed so thatcoordinate systems can serve the precise needs ofnavigation,surveying,cadastre,land use, and various other concerns.

Earth'stopographic surface is apparent with its variety of land forms and water areas. This topographic surface is generally the concern of topographers,hydrographers, andgeophysicists. While it is the surface on which Earth measurements are made, mathematically modeling it while taking the irregularities into account would be extremely complicated.

ThePythagorean concept of aspherical Earth offers a simple surface that is easy to deal with mathematically. Many astronomical and navigational computations use asphere to model the Earth as a close approximation. However, a more accurate figure is needed for measuring distances and areas on the scale beyond the purely local. Better approximations can be made by modeling the entire surface as anoblate spheroid, usingspherical harmonics to approximate thegeoid, or modeling a region with a best-fitreference ellipsoid.

For surveys of small areas, a planar (flat) model of Earth's surface suffices because the local topography overwhelms the curvature.Plane-table surveys are made for relatively small areas without considering the size and shape of the entire Earth. A survey of a city, for example, might be conducted this way.

By the late 1600s, serious effort was devoted to modeling the Earth as an ellipsoid, beginning with French astronomerJean Picard's measurement of a degree of arc along theParis meridian. Improved maps and better measurement of distances and areas of national territories motivated these early attempts. Surveying instrumentation and techniques improved over the ensuing centuries. Models for the figure of the Earth improved in step.

In the mid- to late 20th century, research across thegeosciences contributed to drastic improvements in the accuracy of the figure of the Earth. The primary utility of this improved accuracy was to provide geographical and gravitational data for theinertial guidance systems ofballistic missiles. This funding also drove the expansion of geoscientific disciplines, fostering the creation and growth of various geoscience departments at many universities.[1] These developments benefited many civilian pursuits as well, such as weather and communicationsatellite control andGPS location-finding, which would be impossible without highly accurate models for the figure of the Earth.

The models for the figure of the Earth vary in the way they are used, in their complexity, and in the accuracy with which they represent the size and shape of the Earth.

The simplest model for the shape of the entire Earth is a sphere. The Earth'sradius is thedistance from Earth's center to its surface, about 6,371 km (3,959 mi). While "radius" normally is a characteristic of perfect spheres, the Earth deviates from spherical by only a third of a percent, sufficiently close to treat it as a sphere in many contexts and justifying the term "the radius of the Earth".

The concept of a spherical Earth dates back to around the6th century BC,[2] but remained a matter of philosophical speculation until the3rd century BC. The first scientific estimation of the radius of the Earth was given byEratosthenes about 240 BC, with estimates of the accuracy of Eratosthenes's measurement ranging from −1% to 15%.

The Earth is only approximately spherical, so no single value serves as its natural radius. Distances from points on the surface to the center range from 6,353 km (3,948 mi) to 6,384 km (3,967 mi). Several different ways of modeling the Earth as a sphere each yield a mean radius of 6,371 km (3,959 mi). Regardless of the model, any radius falls between the polar minimum of about 6,357 km (3,950 mi) and the equatorial maximum of about 6,378 km (3,963 mi). The difference 21 km (13 mi) correspond to the polar radius being approximately 0.3% shorter than the equatorial radius.

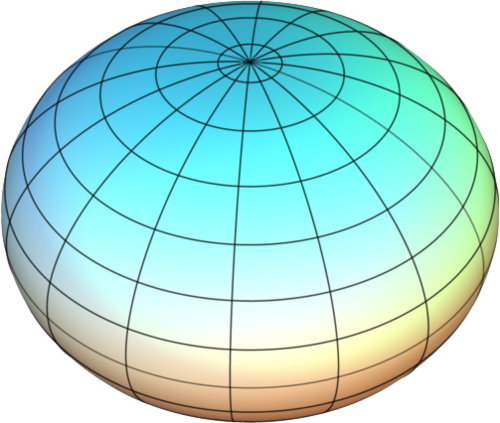

As theorized byIsaac Newton andChristiaan Huygens,[3]: 4 [4][5] the Earth isflattened at the poles andbulged at theequator. Thus,geodesy represents the figure of the Earth as an oblatespheroid. The oblate spheroid, oroblate ellipsoid, is anellipsoid of revolution obtained by rotating an ellipse about its shorter axis. It is the regulargeometric shape that most nearly approximates the shape of the Earth. A spheroid describing the figure of the Earth or othercelestial body is called areference ellipsoid. The reference ellipsoid for Earth is called anEarth ellipsoid.

An ellipsoid of revolution is uniquely defined by two quantities. Several conventions for expressing the two quantities are used in geodesy, but they are all equivalent to and convertible with each other:

Eccentricity and flattening are different ways of expressing how squashed the ellipsoid is. When flattening appears as one of the defining quantities in geodesy, generally it is expressed by its reciprocal. For example, in theWGS 84 spheroid used by today's GPS systems, the reciprocal of the flattening is set to be exactly298.257223563.

The difference between a sphere and a reference ellipsoid for Earth is small, only about one part in 300. Historically, flattening was computed fromgrade measurements. Nowadays, geodetic networks andsatellite geodesy are used. In practice, many reference ellipsoids have been developed over the centuries from different surveys. The flattening value varies slightly from one reference ellipsoid to another, reflecting local conditions and whether the reference ellipsoid is intended to model the entire Earth or only some portion of it.

A sphere has a singleradius of curvature, which is simply the radius of the sphere. More complex surfaces have radii of curvature that vary over the surface. The radius of curvature describes the radius of the sphere that best approximates the surface at that point. Oblate ellipsoids have a constant radius of curvature east to west alongparallels, if agraticule is drawn on the surface, but varying curvature in any other direction. For an oblate ellipsoid, the polar radius of curvature is larger than the equatorial

because the pole is flattened: the flatter the surface, the larger the sphere must be to approximate it. Conversely, the ellipsoid's north–south radius of curvature at the equator is smaller than the polar

where is the distance from the center of the ellipsoid to the equator (semi-major axis), and is the distance from the center to the pole. (semi-minor axis)

The possibility that the Earth's equator is better characterized as an ellipse rather than a circle and therefore that the ellipsoid is triaxial has been a matter of scientific inquiry for many years.[6][7] Modern technological developments have furnished new and rapid methods for data collection and, since the launch ofSputnik 1, orbital data have been used to investigate the theory of ellipticity.[3] More recent results indicate a 70 m difference between the two equatorial major and minor axes of inertia, with the larger semidiameter pointing to 15° W longitude (and also 180-degree away).[8][9]

Following work by Picard, Italian polymathGiovanni Domenico Cassini found that the length of a degree was apparently shorter north of Paris than to the south, implying the Earth to beegg-shaped.[3]: 4 In 1498,Christopher Columbus dubiously suggested that the Earth was pear-shaped based on his disparate mobile readings of the angle of theNorth Star, which he incorrectly interpreted as having varyingdiurnal motion.[10]

The theory of a slightly pear-shaped Earth arose when data was received from the U.S.'s artificial satelliteVanguard 1 in 1958. It was found to vary in its long periodic orbit, with the Southern Hemisphere exhibiting higher gravitational attraction than the Northern Hemisphere. This indicated a flattening at theSouth Pole and a bulge of the same degree at theNorth Pole, with thesea level increased about 9 m (30 ft) at the latter.[11][12][3]: 9 This theory implies the northern middlelatitudes to be slightly flattened and the southern middle latitudes correspondingly bulged.[3]: 9 Potential factors involved in this aberration includetides andsubcrustal motion (e.g.plate tectonics).[11][12]

John A. O'Keefe and co-authors are credited with the discovery that the Earth had a significant third degreezonal spherical harmonic in itsgravitational field using Vanguard 1 satellite data.[13] Based on furthersatellite geodesy data,Desmond King-Hele refined the estimate to a 45 m (148 ft) difference between north and south polar radii, owing to a 19 m (62 ft) "stem" rising in the North Pole and a 26 m (85 ft) depression in the South Pole.[14][15] The polar asymmetry is about a thousand times smaller than the Earth's flattening and even smaller than itsgeoidal undulation in some regions.[16]

Modern geodesy tends to retain the ellipsoid of revolution as areference ellipsoid and treat triaxiality and pear shape as a part of thegeoid figure: they are represented by the spherical harmonic coefficients and, respectively, corresponding to degree and order numbers 2.2 for the triaxiality and 3.0 for the pear shape.

It was stated earlier that measurements are made on the apparent or topographic surface of the Earth and it has just been explained that computations are performed on an ellipsoid. One other surface is involved in geodetic measurement: the geoid. In geodetic surveying, the computation of thegeodetic coordinates of points is commonly performed on areference ellipsoid closely approximating the size and shape of the Earth in the area of the survey. The actual measurements made on the surface of the Earth with certain instruments are however referred to the geoid. The ellipsoid is a mathematically defined regular surface with specific dimensions. The geoid, on the other hand, coincides with that surface to which the oceans would conform over the entire Earth if free to adjust to the combined effect of the Earth's mass attraction (gravitation) and the centrifugal force of theEarth's rotation. As a result of the uneven distribution of the Earth's mass, the geoidal surface is irregular and, since the ellipsoid is a regular surface, the separations between the two, referred to asgeoid undulations, geoid heights, or geoid separations, will be irregular as well.

The geoid is a surface along which the gravitypotential is equal everywhere and to which the direction of gravity is always perpendicular. The latter is particularly important because optical instruments containing gravity-reference leveling devices are commonly used to make geodetic measurements. When properly adjusted, the vertical axis of the instrument coincides with the direction of gravity and is, therefore, perpendicular to the geoid. The angle between theplumb line which is perpendicular to the geoid (sometimes called "the vertical") and the perpendicular to the ellipsoid (sometimes called "the ellipsoidal normal") is defined as thedeflection of the vertical. It has two components: an east–west and a north–south component.[3]

Simpler local approximations are possible.

Thelocal tangent plane is appropriate for analysis across small distances.

The best local spherical approximation to the ellipsoid in the vicinity of a given point is theEarth'sosculating sphere. Its radius equalsEarth's Gaussian radius of curvature, and its radial direction coincides with thegeodetic normal direction. The center of the osculating sphere is offset from the center of the ellipsoid, but is at thecenter of curvature for the given point on the ellipsoid surface. This concept aids the interpretation of terrestrial and planetaryradio occultationrefraction measurements and in some navigation and surveillance applications.[17][18]

Determining the exact figure of the Earth is not only a geometric task of geodesy, but also hasgeophysical considerations. According to theoretical arguments by Newton,Leonhard Euler, and others, a body having a uniform density of 5,515 kg/m3 that rotates like the Earth should have a flattening of 1:229. This can be concluded without any information about the composition ofEarth's interior.[19] However, the measured flattening is 1:298.25, which is closer to a sphere and a strong argument thatEarth's core is extremely compact. Therefore, thedensity must be a function of the depth, ranging from 2,600 kg/m3 at the surface (rock density ofgranite, etc.), up to 13,000 kg/m3 within the inner core.[20]

Also with implications for the physical exploration of the Earth's interior is thegravitational field, which is the net effect of gravitation (due to mass attraction) and centrifugal force (due to rotation). It can be measured very accurately at the surface and remotely by satellites. Truevertical generally does not correspond to theoretical vertical (deflection ranges up to 50") becausetopography and allgeological masses disturb the gravitational field. Therefore, the gross structure of theEarth's crust and mantle can be determined by geodetic-geophysical models of the subsurface.

![]() This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain:Defense Mapping Agency (1983).Geodesy for the Layman (Report). United States Air Force.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in thepublic domain:Defense Mapping Agency (1983).Geodesy for the Layman (Report). United States Air Force.