| African Romance | |

|---|---|

| Region | Roman Africa (Africa Proconsularis/Mauretania Caesariensis/Mauretania Tingitana) Vandal Kingdom Byzantine Africa (Praetorian prefecture/Exarchate of Africa) Mauro-Roman Kingdom Maghreb/Ifriqiya |

| Ethnicity | Roman Africans |

| Era | c. 1st–15th century AD(?) |

Early forms | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

lat-afr | |

| Glottolog | None |

African Romance,African Latin orAfroromance[1] is an extinctRomance language that was spoken in the various provinces ofRoman Africa by theAfrican Romans under the laterRoman Empire and its various post-Roman successor states in the region, including theVandal Kingdom, theByzantine-administeredExarchate of Africa and theBerberMauro-Roman Kingdom. African Romance is poorly attested as it was mainly aspoken,vernacular language.[2] There is little doubt, however, that by the early 3rd century AD, some native provincial variety ofLatin was fully established in Africa.[3]

After theconquest of North Africa by theUmayyad Caliphate in 709 AD, this language survived through to the 8th century in various places along theNorth African coast and the immediate littoral,[2] with evidence that it may have persisted up to the 14th century,[4] and possibly even the 15th century,[3] or later[4] in certain areas of the interior.

TheRoman province of Africa was organized in 146 BC following the defeat ofCarthage in theThird Punic War. The city of Carthage, sacked following the war, was rebuilt during the dictatorship ofJulius Caesar as aRoman colony, and by the 1st century, it had grown to be the fourth largest city of the empire, with a population in excess of 100,000 people.[A] TheFossa regia was an important boundary in North Africa, originally separating the Roman occupied Carthaginian territory fromNumidia,[6] and may have served as acultural boundary indicatingRomanization.[7]

In the time of the Roman Empire, Latin became the second most widely spoken language after Punic, which continued to be spoken in Carthaginian cities and rural areas as late as the mid-5th century.[8] It is probable thatBerber languages were spoken in some areas as well.

Funerarystelae chronicle the partial Romanization of art and religion in North Africa.[9] Notable differences, however, existed in the penetration and survival of the Latin, Punic andBerber languages.[10] These indicated regional differences: Neo-Punic had a revival inTripolitania, aroundHippo Regius there is a cluster ofLibyan inscriptions, while in the mountainous regions ofKabylie andAures, Latin was scarcer, though not absent.[10]

Africa was occupied by theGermanicVandal tribe for over a century, between 429 and 534 AD, when the province was reconquered by the Byzantine EmperorJustinian I. The changes that occurred in spoken Latin during that time are unknown. Literary Latin, however, was maintained at a high standard, as seen in theLatin poetry of the African writerCorippus. The area around Carthage remained fully Latin-speaking until the arrival of the Arabs.

Like all Romance languages, African Romance descended fromVulgar Latin, the non-standard (in contrast toClassical Latin) form of the Latin language, which was spoken by soldiers and merchants throughout the Roman Empire. With theexpansion of the empire, Vulgar Latin came to be spoken by inhabitants of the various Roman-controlled territories inNorth Africa. Latin and its descendants were spoken in theProvince of Africa following thePunic Wars, when the Romans conquered the territory. Spoken Latin, and Latin inscriptions developed while Punic was still being used.[11]Bilingualinscriptions were engraved, some of which reflect the introduction ofRoman institutions into Africa, using new Punic expressions.[11]

Latin, and then some Romance variant of it, was spoken by generations of speakers, for about fifteen centuries.[3] This was demonstrated by African-born speakers of African Romance who continued to create Latin inscriptions until the first half of the 11th century.[3] Evidence for a spoken Romance variety which developed locally out of Latin persisted in rural areas ofTunisia – possibly as late as the last two decades of the 15th century in some sources.[12]

By the late 19th century and early 20th century, the possible existence of African Latin was controversial,[13] with debates on the existence ofAfricitas as a putative Africandialect of Latin. In 1882, theGerman scholarKarl Sittl [de] used unconvincing material to adduce features particular to Latin in Africa.[13] This unconvincing evidence was attacked byWilhelm Kroll in 1897,[14] and again byMadeline D. Brock in 1911.[15] Brock went so far as to assert that "African Latin was free from provincialism",[16] and that African Latin was "the Latin of an epoch rather than that of a country".[17] This view shifted in recent decades, with modern philologists going so far as to say that African Latin "was not free from provincialism"[18] and that, given the remoteness of parts of Africa, there were "probably a plurality of varieties of Latin, rather than a single African Latin".[18] Other researchers believe that features peculiar to African Latin existed, but are "not to be found where Sittl looked for it".[18]

While as a language African Romance is extinct, there is some evidence of regional varieties in African Latin that helps reconstruct some of its features.[19] Some historical evidence on thephonetic andlexical features of theAfri were already observed in ancient times.Pliny observes how walls in Africa andSpain are calledformacei, or "framed walls, because they are made by packing in a frame enclosed between two boards, one on each side".[20]Nonius Marcellus, a Romangrammarian, provides further, if uncertain, evidence regarding vocabulary and possible "Africanisms".[21][B] In theHistoria Augusta, the North AfricanRoman EmperorSeptimius Severus is said to have retained an African accent until old age.[C] More recent analysis focuses on a body of literary texts, being literary pieces written by African and non-African writers.[24] These show the existence of an African pronunciation of Latin, then moving on to a further study of lexical material drawn from sub-literary sources, such as practical texts andostraca, from multiple African communities, that is military writers, landholders and doctors.[24]

The Romance philologistJames Noel Adams lists a number of possible Africanisms found in this wider Latin literary corpus.[25] Only two refer to constructions found in Sittl,[26] with the other examples deriving from medical texts,[27] various ostraca and other non-traditional sources. Two sorts of regional features can be observed. The first areloanwords from a substrate language, such is the case withBritain. In African Latin, this substrate was Punic. The African dialect included words such asginga for "henbane",boba for "mallow,"girba for "mortar" andgelela for the inner flesh of agourd.[28] The second refers to use of Latin words with particular meanings not found elsewhere, or in limited contexts. Of particular note is the African Romance use of the wordrostrum for "mouth" instead of the original meaning in Latin, which is "beak",[29] andbaiae for "baths" being a late Latin and particularly African generalisation from the place-nameBaiae.[30]Pullus meaning "cock" or "rooster", was probably borrowed by Berber dialects from African Romance, for use instead of the Latingallus.[31] The originally abstract worddulcor is seen applied as a probable medical African specialisation relating tosweet wine instead of the Latinpassum ormustum.[32] The Latin forgrape, traditionally indeterminate (acinis), male (acinus) orneuter (acinum), in various African Latin sources changes to the feminineacina.[33] Other examples include the use ofpala as a metaphor for theshoulder blade;centenarium, which only occurs in theAlbertini Tablets and may have meant "granary";[34] andinfantilisms such asdida, which apparently meant "breast/nipple" or "wet nurse".[35] A few African Latin loanwords from Punic, such asmatta ("mat made of rushes", from which derives English "mat") and Berber, such asbuda ("cattail") also spread into general Latin usage, the latter even displacing native Latinulva.[36]

Both Africans, such asAugustine of Hippo and the grammarianPompeius, as well as non-Africans, such asConsentius andJerome, wrote on African features, some in very specific terms.[37] Indeed, in hisDe Ordine, dated to late 386, Augustine remarks how he was still criticised by theItalians for hispronunciation, while he himself often found fault with theirs.[38] While modern scholars may express doubts on the interpretation or accuracy of some of these writings, they contend that African Latin must have been distinctive enough to inspire so much discussion.[39]

Prior to theArab conquest in 696–705 AD, a Romance language was probably spoken alongsideBerber languages in the region.[40] Loanwords from Northwest African Romance to Berber are attested, usually in theaccusative form: examples includeatmun ("plough-beam") fromtemonem.[40]

Following the conquest, it becomes difficult to trace the fate of African Romance. The Umayyad administration did at first utilize the local Latin language in coinage from Carthage andKairouan in the early 7th century, displaying Latin inscriptions of Islamic phrases such asD[e]us tu[us] D[e]us et a[li]us non e[st] ("God is your God and there is no other"), a variation of theshahada, or Muslim declaration of faith.[41] Conant suggests that African Romance vernacular could have facilitated diplomatic exchange betweenCharlemagne and theAghlabid emirate, as the Frankish-given name for the Aghlabid capital isFossatum (Latin for fortifications) which is reflected in the name todayFusātū.[42]

African Latin was soon replaced by Arabic as the primaryadministrative language, but it existed at least until the arrival of theBanu Hilal Arabs in the 11th century and probably until the beginning of the 14th century.[43] It was spoken in various parts of the littoral of Africa into the 12th century,[2] exerting a significant influence onNorthwest African Arabic, particularly the language of northwesternMorocco.[40]

Amongst the Berbers of Ifriqiya, African Romance was linked to Christianity, which survived in North Africa (outside of Egypt) until the 14th century.[4] Christian cemeteries excavated in Kairouan dating from 945 to 1046 and in Áin Zára and En Ngila in Tripolitania from before the 10th century contain Latin inscriptions demonstrating continued use of written liturgical Latin centuries into Islamic rule; graves with Christian names such as Peter, John, Maria, Irene, Isidore, Speratus, Boniface and Faustinus contain common phrases such as "requiem aeternam det tibi Dominus et lux perpetua luceat tibi ("May the Lord give you eternal rest and everlasting light shine upon you") orDeus Sabaoth from theSanctus hymn. Anotherexample attests to the dual usage of the Christian and theHijri calendars, reading that the deceased died inAnno Domini 1007 or 397annorum infidelium ("Years of the infidels".)[44] There is also aVetus LatinaPsalter inSaint Catherine's Monastery dated to 1230, which has long been attributed to African origin due to its usage of African text and calendar of saints.[45] The Psalter notably contains spellings consistent with Vulgar Latin/African Romance features (see below), such as prothetici insertion, repeated betacism in writingb forv and substituting second declension endings to undeclinable Semitic biblical names.[46] Written Latin continued to be the language of correspondence between African bishops and the Papacy up till the final communication betweenPope Gregory VII and the imprisoned archbishop of Carthage,Cyriacus in the 11th century.[47] Spoken Latin or Romance is attested inGabès byIbn Khordadbeh; inBéja,Biskra,Tlemcen, andNiffis byal-Bakri; and inGafsa andMonastir byal-Idrisi,[2] who observes that the people in Gafsa "are Berberised, and most of them speak the African Latin tongue."[2][48][D] In the passage, Al-Idrisi mentions that "there is a fountain calledal-ṭarmid", which could derive fromtherma ("hot bath".)[49] There is also a possible reference to spoken Latin or African Romance in the 11th century, when theRustamid governor Abu Ubayda Abd al-Hamid al-Jannawni was said to have sworn his oath of office in Arabic, Berber and in an unspecified "town language", which might be interpreted as a Romance variety; in the oath, the Arabic-rendered phrasebar diyyu could represent some variation of Latinper Deu(m) ("by God".)[50]

In their quest to conquer theKingdom of Africa in the 12th century, theNormans were aided by the remaining Christian population of Tunisia, who some linguists, among themVermondo Brugnatelli [it], argue had been speaking a Romance language for centuries.[51]

The final attestations of African Romance come from the Renaissance period. The 15th century Italian humanistPaolo Pompilio [it] makes the most significant remarks on the language and its features, reporting that a Catalan merchant named Riaria who had lived in North Africa for thirty years told him that the villagers in theAurès mountain region "speak an almost intact Latin and, when Latin words are corrupted, then they pass to the sound and habits of theSardinian language".[52] The 16th century geographer and diplomatLeo Africanus, who was born into a Muslim family inGranada and fled theReconquista to Morocco, also says that the North Africans retained their own language after the Islamic conquest which he calls "Italian", which must refer to Romance.[53] A statement byMawlā Aḥmad is sometimes interpreted as implying the survival of a Christian community inTozeur into the eighteenth century, but this is unlikely; Prevost estimates that Christianity disappeared around the middle of the thirteenth century in southern Tunisia.[4]

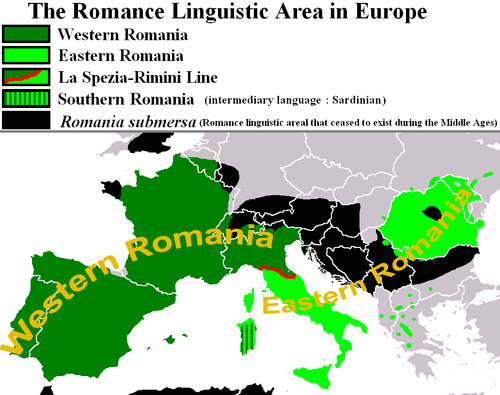

The most prominent theory for the classification of African Romance (at least for the interior province ofAfrica Proconsularis) is that it belonged to a shared subgroup along withSardinian, calledSouthern Romance by some linguists. This branch of Romance, of which Sardinian would today be the only surviving member, could have also been spoken in the medieval period inCorsica prior to the island's Tuscanization,[54] southernBasilicata (eastern region of theLausberg area) and perhaps other regions in southern Italy,Sicily and possibly evenMalta.

A potential linguistic relationship between Sardinia and North Africa could have been built up as a result of the two regions' long pre-Roman cultural ties starting from the 8th-7th centuries BC, when the island fell under theCarthaginian sphere of influence. This resulted in thePunic language being spoken in Sardinia up to the 3rd–4th centuries AD, and several Punic loan-words survive into modern Sardinian.[55][56]Cicero also mocks Sardinia's perceived Carthaginian and African cultural identity as the source of its inferiority and disloyalty to Rome.[E] The affinity between the two regions persisted after the collapse of theWestern Roman Empire under shared governance by theVandal Kingdom and then the ByzantineExarchate of Africa. Pinelli believes that the Vandal presence had "estranged Sardinia from Europe, linking its own destiny to Africa's territorial expanse" in a bond that was to strengthen further "under Byzantine rule, not only because the Roman Empire included the island in the African Exarchate, but also because it developed from there, albeit indirectly, its ethnic community, causing it to acquire many of the African characteristics".[57]

The spoken variety of African Romance was perceived to be similar to Sardinian as reported in the above-cited passage byPaolo Pompilio [it][F] – supporting hypotheses that there were parallelisms between developments of Latin in Africa andSardinia. Although this testimony comes from a secondhand source, the Catalan merchant Riaria, these observations are reliable since Sardinia was under Catalan rule by theCrown of Aragon, so the merchant could have had the opportunity to trade in both regions.[12]

Augustine of Hippo writes that "African ears have no quick perception of the shortness or length of [Latin] vowels".[59][60][G] This also describes the evolution ofvowels in Sardinian. Sardinian has only five vowels, and no diphthongs; unlike the other survivingRomance languages, the five long vowel pairs ofClassical Latin,ā, ē, ī, ō, ū (phonetically [aː, eː, iː, oː, uː]), merged with their corresponding short vowel counterpartsă, ĕ, ĭ, ŏ, ŭ [a, ɛ, ɪ, ɔ, ʊ] into five single vowels with no length distinction: /a, ɛ, i, ɔ, u/.[H] In theItalo-Western Romance varieties, shortǐ, ŭ [ɪ, ʊ] merged with longē, ō [e(ː), o(ː)] instead of with longī, ū [i(ː), u(ː)] as in Sardinian, which typically resulted in a seven vowel system, for example /a, ɛ, e, i, ɔ, o, u/ inItalian.

Adams theorises that similarities in some vocabulary, such aspala ("shoulderblade") andacina ("grape") across Sardinian and African Romance, orspanu[62] in Sardinian andspanus ("light red") in African Romance, may be evidence that some vocabulary was shared between Sardinia and Africa.[63] A further theory suggests that the Sardinian word for "Friday",cenàpura orchenàpura (literally "pure dinner", in reference toparasceve, or Friday preparation for theSabbath),[64] may have been brought to Sardinia byNorth African Jews. The termcena pura is used by Augustine, although there is no evidence that its meaning in Africa extended beyond the Jewish religious context to simply refer to the day of Friday.[65] It is further speculated that the Sardinian word for the month of June,lámpadas ("lamps"), could have a connection to African usage due to references byFulgentius and in a work on theNativity of John the Baptist to adies lampadarum ("day of the lamps") during the harvest in June.[66] Celebrations on the Feast of St. John the Baptist involving torches appear to have been Christianized solstice ceremonies originally dedicated toCeres, and have also been attested in Spain byRodrigo Caro aslámpara and in Portugal asSão João das Lampas ("St. John of the Torches").[67] There is also possible evidence of shared Sardinian and African Latin vocabulary in that Latincartallus ("basket") results in the unique Sardinian wordiscarteddu andMaghrebi Arabicgertella.[68] Additionally, it is notable that Sardinian is the only Romance language in which the name for theMilky Way,sa (b)ía de sa bálla / báza, meaning "the Way of Straw", also occurs in Berber languages, hinting at a possible African Romance connection.[69]

Blasco Ferrer suggests that the Latin demonstrativeipse/-a, from which derive both the Sardiniandefinite articlesu/sa as well as thesubject personal pronounsisse/-a, could have syncretized with theBerber feminine prefixta in African Latin. Apart from Sardinian, the only other Romance varieties which take their article fromipse/-a (instead ofille/-a) are the Catalan dialects of theBalearic Islands, certain areas of Girona, the Vall de Gallerina and Tàrbena, Provençal and medieval Gascon. Blasco Ferrer proposes that usage ofipse/-a was preferred overille/-a in Africa under southern Italian influence, as observed in the 2nd century Act of theScillitan Martyrs (Passio Scillitanorum) which substitutesipse/-a forille/-a. This dialectal form then could have developed into*tsa, which is attested inOld Catalan documents like theHomilies d'Organyà (e.g.za paraula: "the words"), and traversed the Mediterranean from Africa to Sardinia, the Balearics and southern Gaul. The justification for positing Berberta as possibly derivative ofipsa is that its allophonic pronunciation is [θa], which is often the phonetic outcome in Berber of [tsa].[70] However, the connection betweenipsa andta remains highly speculative and without direct evidence.

Writing in the 12th century,Muhammad al-Idrisi additionally observes cultural similarities between Sardinians and Roman Africans, saying that "theSardinians are ethnically[71] Roman Africans, live like theBerbers, shun any other nation ofRûm; these people are courageous and valiant, that never part with their weapons."[72][73][I]

There is also possible evidence of dialectal unity across the Latin-speaking southern Mediterranean, from Hispania to Africa and up to Sardinia and Sicily. AlthoughSicilian is typically not included in the Southern Romance group due to itsdistinct vocalism from the Afro-Sardinian outcome, Sicily, parts of Southern Italy (particularly SouthernBasilicata, within theLausberg area, Sardinia and Corsica (prior to the island's Tuscanization)[75] and perhaps even Malta could have at one time formed a Latin/Romance dialectal continuum.

Blasco Ferrer hypothesizes that Africa Proconsularis, a center of linguistic prestige (home of renowned writers likeAmmianus Marcellinus,Appianus,Terence,Tertullian andSt. Augustine) and agricultural importance,[76] showing that African Latin, Sardinian, Sicilian and Hispano-Romance share certain characteristics dating from the pre-Roman and Roman periods. Influences from the unknown pre-Roman non-or early Indo-European "Mediterran substratum" found across all four regions include the use of the suffix-itanus to indicate ethnicity (e.g., in AfricaAggaritani,Assalitani,Belalitani; in HispaniaAurgitani,Ausetani,Bastetani,Calagurritani; in SardiniaCaralitani,Celsitani,Giddilitani,Campitani,Sulcitani; in SicilyDrepanitani,Gaulitani,Hadranitani,Liparitani, as well as placenamesLocritano andReitano in Calabria) and the occasionally the suffix-ara to indicate plurality (e.g., in AfricaMákaras,Biracsáccara; in HispaniaBràcana/Bràcara,Làncara; inEgara,Gàndara,Tàbara,Tàmara, in SardiniaMàndara,Ardara; in Sicily,Hykkara,Indara,Màcara,Lípara/i,Màzara.)[77]

Common Latin-internal linguistic developments found in Africa, Sardinia and Sicily, which could have radiated out to the islands from the African Latin dialect, include the tendency to lose /u/ in the 2nd declension-ius/-ium endings (e.g., in AfricaValerius >Valeris,Ianuarius >Ianuaris,Martius >Martis,Nasidi(u)s,Superi(u)s; in Sicily,Salusi(us),Taracius >Tarasi(us),Laeli(us),Blasi(us);Vitali(u)s; in Sardinia,cinisium >ginisi (as well as the last-nameSanginisi); in Sardinia,Vitali(u)s,Simpliki,Sissini);Antoni and sporadic voicing of initial /g/ (e.g., in Africa,Quiza > Maghrebi ArabicGiza/Guzza,communes >gommunes; in Sicily,ginisi,Sanginisi,San Ginesio (toponym); in Sardinia,ghinisu, Lat.carricare,carduus >garrigare,gardu.[78] Further, the replacement of the 3rd declension suffix-ensis for place origin with a 2nd declensions variant*-ensus is attested only in Sardinia (e.g.campidanesu,logudoresu) and in Africa (Arnensis >Arnensus.)[79] Also, it is noted that the conservation of final /s/, found today in Sardinian andLucanian, is attested in Maghrebi/Siculo-Arabic loanwords from African Latin (e.g.,capis >qābis;ad badias >Bādiş,Badeş;casas >qāsās,comes >k.mm.s;cellas >k.llas and Sicilian (e.g.,cannes >qan(n)es;capras >q.br.s;triocalis >t.r.q.l.s) (see below for details.)[80]

In the area of vocabulary, Blasco Ferrer believes based on the above-mentioned phonetic developments and geographic restriction to either Sicily, parts of Calabria or Sardinia that the lexical variants *cinisium ("ash", yielding Sardinianghinisu, Sicilianginisi) instead of standard Latincinis > Italiancenere),opacus + *cupus ("dark", yielding Sicilian and Calabrianaccupàri,accupúsu,occúpu,capúne, Sardinianbaccu) andopacus +vacuus (yielding Sardinianbaccu), variants officatum ("liver") with stress shift to the initial syllable (e.g., ['fi:katũ]), yielding Central Sardinianfìcatu,ìcatu, Sicilian and Calabrianfìccatu, Spanishhígado, must have radiated northward from Africa.[81]

Some scholars also theorise that many of theNorth African invaders of Hispania in theEarly Middle Ages spoke some form of African Romance,[82] with "phonetic,morphosyntactic, lexical andsemantic data" from African Romance appearing to have contributed in the development ofIbero-Romance."[83] It is suggested that African Latinbetacism may have pushed the phonological development of Ibero-Romance varieties in favor of the now characteristic Spanishb/v merger as well as influencing the lengthening of stressed short vowels (after the loss of vowel length distinction) evidenced in lack of diphthongization of shorte/o in certain words (such asteneo >tengo ("I have"),pectus >pecho ("chest"),mons >monte ("mountain".)[84] In the area of vocabulary, it is possible that the meaning ofrostrum (originally "bird beak") may have changed to mean "face" (of humans or animals), as in Spanishrostro, under the influence of African usage, and the African Latin-exclusive wordcentenarium ("granary") may have yielded the names of two towns inHuesca calledCentenero.[85] Adamik also finds evidence for dialectological similarity betweenHispania and Africa based on rates of errors in the case system, a relation which could have increased from the 4th-6th centuries AD but was disrupted by the Islamic invasion.[86]

Some evidence could point towards an alternate development for the Latin spoken in the province ofMauretania in western North Africa. Although agreeing with previous studies that the Late Latin of the interior province ofAfrica Proconsularis certainly displayed Sardinian vocalism, Adamik argues based on inscriptional evidence that the vowel system was not uniform across the entirety of the North African coast, and there is some indication that the Latin variety ofMauretania Caesariensis was possibly changing in the direction of the asymmetric six-vowel system found inEastern Romance languages such as Romanian: /a, ɛ, e, i, o, u/. In Eastern Romance, on the front vowel axis shortǐ [ɪ] merged with longē [e(ː)] as /e/ while keeping short ĕ /ɛ/ as a separate phoneme (as in Italo-Western Romance), and on the back vowel axis shortŭ [ʊ] merged with longū [u(ː)], while shortŏ [ɔ] merged with longō [o(ː)] as /o/ (similar to in Sardinian.)[87] Due to the vast size of Roman territory in Africa, it is indeed plausible (if not likely) based on the analysis above that multiple distinct Romance languages had evolved there from Latin.

Scholars including Brugnatelli and Kossmann have identified at least 40 words in variousBerber dialects which are certain to have been loans from Latin or African Romance. For example, inGhadames the word "anǧalus" (ⴰⵏⴳⴰⵍⵓⵙ,أندجالوس) refers to a spiritual entity, clearly using a word from the Latinangelus "angel".[88][89] A complete list of Latin/Romance loanwords is provided below under the section on Berber vocabulary.

Some impacts of African Romance onMaghrebi Arabic andMaltese are theorised.[90] For example, incalendarmonth names, the wordfurar "February" is only found in the Maghreb and in theMaltese language – proving the word's ancient origins.[90] The region also has a form of another Latin named month inawi/ussu < augustus.[90] This word does not appear to be a loan word through Arabic, and may have been taken over directly from Late Latin or African Romance.[90] Scholars theorise that a Latin-based system provided forms such asawi/ussu andfurar, with the system then mediating Latin/Romance names through Arabic for some month names during the Islamic period.[91] The same situation exists for Maltese which mediated words fromItalian, and retains both non-Italian forms such asawissu/awwissu andfrar, and Italian forms such asapril.[91] Lameen Souag likewise compares several Maltese lexical items with Maghrebi Arabic forms to show that these words were borrowed directly from African Latin, rather than Italian or Sicilian.Bumerin ("seal"), coming from Latinbos marinus ("sea cow"), matchesDellysbū-mnīr and Moroccanbū-mrīn. In the case of Malteseberdlieqa ("purslane") from Latinportulaca, equivalent Arabic words are found throughout North Africa and formeral-Andalus, includingbǝrdlāqa in Dellys,bardilāqaš inAndalusi Arabic andburṭlāg in the desert regions ofEl Oued.[92] As mentioned above, the Maghrebi Arabic wordgertella ("basket"), from Latincartallus, could also hint at a promising African Romance-Sardinian lexical connection with the unique Sardinian wordiscarteddu.[68] Lastly, in the area of grammar, Heath has suggested that the archaicMoroccan Arabic genitive particled could have derived from Latinde, as in Romance languages, although this structure is absent from Maltese and other Maghrebi Arabic varieties, making the theory controversial.[92]

Starting from African Romance's similarity with Sardinian, scholars theorise that the similarity may be pinned down to specific phonological properties.[12] Logudorese Sardinian lackspalatization ofvelar stops before front vowels, and features the pairwise merger of short and long non-low vowels.[3] Evidence is found that bothisoglosses were present in at least certain varieties of African Latin:

The Polish ArabistTadeusz Lewicki tried to reconstruct some sections of this language based on 85 lemmas mainly derived from Northwest Africantoponyms andanthroponyms found in medieval sources.[129] Due to the historical presence in the region of Classical Latin, modern Romance languages, as well as the influence of theMediterranean Lingua Franca (that has Romance vocabulary) it is difficult to differentiate the precise origin of words inBerber languages and in the varieties ofMaghrebi Arabic. The studies are also difficult and often highly conjectural. Due to the large size of the North African territory, it is highly probable that not one but several varieties of African Romance existed, much like the wide variety of Romance languages in Europe.[130] Moreover, other Romance languages spoken in Northwest Africa before theEuropean colonization were theMediterranean Lingua Franca,[131] apidgin with Arabic and Romance influences, andJudaeo-Spanish, a dialect of Spanish brought bySephardi Jews.[132] Scholars are uncertain or disagree on the Latin origin of some of the words presented in the list, which may be attributed alternatively to Berber language internal etymology.[133]

Scholars believe that there is a great number of Berber words, existing in various dialects, which are theorised to derive from late Latin or African Romance, such as the vocabulary in the following list. It might be possible to reconstruct a chronology of which loans entered Berber languages in the Classical Latin period versus in Late Latin/Proto-Romance based on features; for example, certain forms such asafullus (frompullus, "chicken") orasnus (<asinus, "donkey") preserve the Classical Latin nominative ending-us, whereas other words likeurṭu (<hortus, "garden") ormuṛu (<murus, "wall") have lost final-s (matching parallel developments in Romance, perhaps in deriving from the accusative form after the loss of final-m.)[134] Forms such astayda (<taeda, "pinewood"), which seem to preserve the Latin diphthongae, might also be interpreted as archaic highly conservative loans from the Roman Imperial period or earlier.

However, the potential chronological distinction based on word endings is inconsistent; the formqaṭṭus (fromcattus, "cat") preserves final-s, butcattus is only attested in Late Latin, when one would expect final-s to have been dropped.[135] Further, the-u endings may instead simply derive from accusative forms which had lost final-m; as a comparison, words drawn from 3rd declension nouns may vary between nominative-based forms likefalku <falco ("falcon"), and accusative/oblique-case forms likeatmun <temo (Acc:temonem, "pole", cf. Italiantimone) oramerkidu ("divine recompense") <merces (Acc:mercedem, "pay/wages", cf. Italiianmercede.)[134]

Nevertheless, when undisputed Latin-derived Berber words are compared with corresponding terms in Italian, Sardinian, Corsican, Sicilian and Maltese, shared phonological outcomes with Sardinian (and to some extent Corsican) seem apparent. For evidence of the merger of Latin shortǐ, ŭ [ɪ, ʊ] with /i, u/ instead of /e, o/, compare how Latinpirus/a ("pear tree/pear") results in Berberifires and Sardinianpira vs. Italianpero, and Latinpullus ("chicken") becomes Berberafullus and Sardinianpuddu vs. Italianpollo. For evidence of a lack of palatalization of velar stops, notice how Latinmerces ("pay/wages") results in Berberamerkidu and Sardinianmerchede vs. Italianmercede, Latincicer ("chickpea") becomes Berberikiker and Sardinianchìghere vs. Italiancece and Latincelsa becomes Berbertkilsit and Sardinianchersa vs. Italiangelso and Latinfilix (genitivefilicis, "fern") becomes Berberfilku and Sardinianfilighe vs. Italianfelce . For evidence to the contrary in favor of palatalization of velar stops, seecentenum >išenti,angelus >anǧelus (dialectally, with other varieties displaying non-palatalized forms), etc. andagaricellus >argusal/arsel.

| English | Berber | Latin | Sardinian | Italian | Corsican | Sicilian | Maltese[136] | |

| sin / sickness / little child (lit., "without sin") | abekkaḍu / abăkkaḍ[137][138] / war-abekkadu / war-ibekkaden[139] | peccatum ("sin"; "error"; "fault") | pecadu / pecau ("sin") | peccato ("sin") | pecatu ("sin") | piccatu ("sin") | ||

| wether (castrated ram)[140] | aberkus[122] | vervex / berbex > *berbecus(?) | berbeghe / berveghe / barveghe / barbeghe / verveche / berbeche / erveghe / ilveghe/ barbei / brabei / brebei / erbei / arbei / brobei / ebrei | berbice | ||||

| celery | abiw[141] | apium ("celery"; "parsley") | àpiu / àppiu | appio | accia | |||

| road / path | abrid / tabrida[142] | veredus ("fast or light breed of horse") | ||||||

| oven | afarnu[143] / affran / afferan / ufernu / ferran[144] / afurnu / tafurnut[145] | furnus | furru / forru | forno | fornu / forru / furru | furnu | forn | |

| chicken / chick | afullus[115] / afellus / fiǧǧus / fullis[146] | pullus | puddu | pollo | pullastru | puḍḍu / pollu | fellus | |

| fresh curd / to curdle / curdled milk | aguglu / kkal / ikkil[147] | coagulari / coagulum ("to curdle"; "curd"; "bind/bonding agent"; "rennet"; "rennet") | callu / cazu / cracu / cragu / giagu ("rennet") | caglio ("rennet") | caghju ("rennet") | quagghiu / quagliu ("rennet") | ||

| agaric | agursal / arsel[148] | agaric > *agaricellum | agarico | agarico | ||||

| boat | aɣeṛṛabu[134] | carabus | ||||||

| oak | akarruš / akerruš[149][150] | cerrus / quercus | chercu | quercia | quercia | querchia | ||

| elevated part of the bedroom | alektu / řeštu[151] | lectus ("bed") | letu ("bed") | letto ("bed") | lettu ("bed") | lettu ("bed") | ||

| oleander | alili / ilili / talilit[152][153] | lilium (lily) | lizu / lilliu / lillu / lixu / lìgiu / gixu / gìgliu / gìsgiu ("lily") | giglio ("lily") | gigliu ("lily") | gigghiu ("lily") | ġilju ("lily") | |

| alms / religious compensation | amerkidu / amarkidu / emarked / bu-imercidan[88] | merces ("pay"; "wages"; "reward"; "punishment"; "rent"; "bribe") | merchede ("pay"; "recompense")[154] | mercede ("recompense"; "merit"; "pity"; "mercy") | mercedi / mircedi ("remuneration"; "payment"; "wage"; "salary"),merci (merchandise"; "goods") | |||

| olive marc | amuṛeǧ[155] | amurca | morchia | mùrija / muria | ||||

| angel / spiritual entity / child / type of illness | anǧelus / anǧalus / anglus / ănǧălos / ăngălos / anaǧlusan / wanaǧlusan / anglusen[156][89][157] | angelus | àgnelu / ànzelu / ànghelu / àngelu | angelo | anghjulu | àncilu / ànciulu | anġlu | |

| to light up / illuminate / light / lamp[158] | amnar[159] | limino, liminare / lumino, luminare | luminare | |||||

| (large) sack / double bag/donkey's saddle / tapestry | asaku / saku / sakku / saču[160][161][144] | saccus | sacu | sacco | saccu | saccu | saqqu | |

| donkey / ass | asnus[122] | asinus | àinu | asino | asinu | àsinu | ||

| belonging to or attached to a yoke | ašbiyo / ašbuyo[162] | subiugius | sisùja / susùja | soggiogo | ||||

| helm | aṭmun / aṭmuni[163][95][146][155] | temo ("pole"; "tongue of carriage"; "beam") | timona / timone / timoni | timone | timone | timuni | tmun | |

| August | awussu[164] | augustus | agustu / austu | agosto | aostu / agostu | Austu | Awwissu / Awissu | |

| blite | blitu[165] | blitum | bieta ("beet": frombeta, "beet" +blitum, "blite") | jiti / ajiti / agghiti / gidi / nciti / aiti ("beet": frombeta, "beet" +blitum, "blite") | ||||

| young boy | bušil[166] | pusillus ("small") | pusiddu ("small boy")[68] | pusillo ("small") | ||||

| thrush (bird, in familyturdidae | ḍerḍus / ḍorḍus[167] | turdus | tordo | tôdula | turdu | |||

| large wooden bowl | dusku[168][169] | discus | discu | disco | discu | |||

| (drawing) rule / vertical beam of weaving loom | errigla[170] | regula ("rule / bar / ruler") | regra / arregra / rega / rega / regia / reja | reglio (rare) /regola (later borrowing) | rica / riga | règula/ rèjula (later borrowing) | regola (later borrowing) | |

| bearded vulture / bird of prey | falku / afalku / afelkun / fařšu[134] | falco ("falcon") | falco / falcone ("falcon") | falcu ("falcon") | farcu / farcuni / falcuni ("falcon") | falkun ("falcon") | ||

| locality in Tripolitania | Fassaṭo[171] | fossatum(?) ("ditch", e.g. as fortification) | fossato ("ditch") | fussatu ("ditch") | foss ("ditch") | |||

| pennyroyal | fleyyu / fliyu / fleggu[172] | pulegium / puleium / puledium / pulleium / pulledium | poleggio / puleggio | |||||

| February | furar[173] | februārius | freàrgiu / frearzu / fiàrzu | febbraio | ferraghju / farraghju / frivaghju | Frivaru | Frar | |

| hen-house | gennayru[144] | gallinarium | gallinaio | gaḍḍinaru / jaḍḍinaru | ||||

| castle / village | ɣasru[174][134] | castrum (diminutive:castellum) | casteddu | castello | castellu | casteḍḍu | qasar / kastell | |

| bean | ibaw[175][176] / awaw[177][178] | faba | faa / faba / fae / fava | fava | fava / fafa | |||

| evil spirit | idaymunen[138][157] | daemon / daemonium ("lar, household god"; "demon, evil spirit") | demone / demonio | dimoniu | dimoniu | |||

| fern | ifilku | filix | filiche / filighe / filixi / fibixi / fixibi | felce | filetta | fìlici | felċi | |

| thread | ifilu[155] | filum(?) ("thread; string; filament; fiber")[179] | filu | filo | filu | filu | ||

| vulture[180] | i-gider[142] | vultur | avvoltoio / avvoltore / voltore / vultore / vulture | vuturu / avuturu | avultun | |||

| pear / pear tree | ifires / tfirast / tafirast[172][36] | pirus (feminine:pira, "pear fruit") | pira ("pear fruit") | pero | pera ("pear fruit") | piru | ||

| cultivated field | iger / ižer[181] | ager | agru | agro | acru | agru | ||

| laborer (to plough) | ikerrez[155] | carrus ("wagon; cart; wagonload", from Gaulish) | carru | carro | carru | |||

| chickpea | ikiker[94] | cicer | chìghere / cìxiri | cece | cecciu | ciciri | ċiċri | |

| horehound | immerwi[182] | marrubium | marrubiu | marrubio | marrubbiju | marrubja | ||

| sea squill / sea onion (Drimia maritima) | isfil[162] | squilla / scilla | aspidda | squilla | ||||

| rye | išenti / tāšentit[148] | centenum ("rye; something gathered hundred each") | ||||||

| durmast | iskir[183][184] | aesculus | eschio / ischio | |||||

| fig (in the stage of pollination) / artichoke | karḍus (first definition)[134] /ɣerdus / ɣerda (second definition)[167] | carduus ("thistle"; "artichoke") | cardo ("thistle") | cardu ("thistle") | cardu ("thistle") | |||

| bug / bedbug | kumsis[122] | cimex | chímighe | cimice | cimicia | cìmicia | ||

| wall | muṛu / maṛu[185] | murus | muru | muro | muru | muru | ||

| cat | qaṭṭus / takaṭṭust / yaṭṭus / ayaḍus / qeṭṭus[186][146] | cattus | gatu / atu / batu / catu | gatto | ghjattu / gattu / ghiattu | jattu | qattus | |

| Rif (locality in Morocco) | Rif[171] | ripa(?) ("shore"; "bank") | ripa ("shore"; "bank") | |||||

| feast / religious celebration / springtime | tafaska / tafaske / tabaski / tfeskih[187] | pascha ("Easter"; "Passover") | Pasca ("Easter") | Pasqua ("Easter") | Pasqua ("Easter") | Pasqua ("Easter") | ||

| cauldron / iron bowl / cooking jug | tafḍna / tafeḍna / tafaḍna[144] | patina ("shallow pan or dish for cooking"; type of cake; "crib") | patina ("patina"; "coat"; "film"; "glaze"; "size") | |||||

| carrot | tafesnaxt[141] | pastinaca ("parsnip"; "stingray") | pastinaca / pistinaga / frustinaca ("parsnip"; "carrot") | pastinaca ("parsnip") | pastinaccia / pastricciola ("parsnip") | bastunaca / vastunaca ("parsnip") | ||

| bud or eye of a plant / gem / jewel[158] | tagemmut[162] | gemma | gemma | |||||

| crow | tagerfa[170] | corvus[188] | colbu / crobu / colvu / corbu / corvu | corvo | corbu | corvu / corbu | ||

| throat | tageržumt[189] | gurga(?)(Late Latin, fromgurges, "whirlpool") | gorgia (archaic) | gargiularu | gerżuma | |||

| thing | taɣawsa / tɣawsa[138] / taghaussa / tghussa[190][191] | causa ("case"; "reason/cause"; "motive"; "condition/state"; "justification") | cosa (inherited from Italian; Old Sardinian,casa) | cosa | còsa | cùosa | ||

| various toponyms | Taɣlis / Taɣlisiya[192] / iglazen / iglis / Tarlist[193] | ecclesia(?) ("church") | chegia / cheja / creia / crèsia ("church") | chiesa ("church") | chiesa / ghiesgia / jesgia ("church") | chìesa / chisa / chesa / clesia / crèsia / crièsia ("church") | ||

| wax | takir[68] | cera | chera / cera | cera | cera | cira | ||

| quince | taktuniyt / taktunya[172] | (malum) cydonium / cotonium / cotoneum (pluralcydonium / cotonia) | chidonza / chintonza / chitonza | cotogno ("quince tree") /cotogna ("quince fruit") | melacutona / melacutugnu | cutugnu / cutugna | ||

| seaweed | talga[146] | alga | alga | alga | àlica | alka | ||

| file | talima / tilima / tlima[144][194] | lima | lima | lima | lima | |||

| irrigation channel | targa[51] | *riga(?) <irrigo("to water/irrigate/flood")[195] | irrigare ("to irrigate") | irrigà ("irrigate") | ||||

| weapon | tarma[51] | arma | àrma | arma | arma | arma | arma | |

| madder (red-dye) | tarubi / tarubya / tarrubya / awrubya / tṛubya[172] | rubia | robbia | |||||

| ladder | taskala[141] | scala ("ladder"; "stairs") | iscala / issala / scaba | scala | scala | scala | ||

| pod (of pea or bean) / carob | tasligwa / tasliɣwa / tisliɣwa / tasliwɣa[172][68] | siliqua | silimba / silibba / tilimba / tilidda[68] | serqua | ||||

| pair / pair of drought animals, oxen | tawgtt / tayuga / tayugʷa / tayuggʷa / tyuya / tiyuyya / tiyuga / tǧuǧa / tguget / tiugga[146] | iugum ("pair of drought animals"; "yoke"; "couple") | jugu /giugu /giuu ("yoke") | giogo ("yoke") | jugu ("yoke") | giugu ("yoke") | ||

| pine | tayda[146] | taeda ("pinewood") | teda | deda | ||||

| shirt | tekamest[141] | camisia | camigia / camisa | camicia | camisgia / camigia / camicia | cammisa | qmis | |

| elbow | tiɣammar / taɣomert / tiɣumert[167] | camur <camur ("bent"; "curved"; "hooked") | cambra ("clamp"; "cramp") | |||||

| lentil | tilintit / tiniltit[172] | lens | lènte / lentìza | lente / lenticchia | lintichja | lenti / linticchia | ||

| shoemaker's awl | tissubla / tisubla / tsubla / tasubla / tasobla / tasugla / subla[144] | subula | subbia ("chisel") | |||||

| catapult | tfurka[141] / afurk / tfurket[145] | furca ("fork"; "pitchfork"; "pole"; "stake") | frúca / furca ("fork"; "pitchfork") | forca ("fork"; "pitchfork") | furca ("fork"; "pitchfork") | |||

| mulberry tree | tkilsit[93] / tkilsa | (morus) celsa[141] | chersa / chessa | gelso / moro | ceusu | |||

| piece of paper | tkirḍa / tkurḍa / takerḍa / takarḍe, tyerṭa[138] | carta / charta ("paper"; "papyrus") | carta / calta | carta | carta | carta | karta | |

| wooden board for making doors / irrigable field (second two forms listed) | toḍabla[135] / taġult / tiġula[162] | tabula ("board"; "tablet") | taula ("piece of wood") | tavola ("table"; "slate") | tavula ("table") | tàvula ("table") | ||

| theater[140] | ṭyaṭir[167] | theatrum | teatru | teatro | teatru | tiatru | teatru | |

| wooden board for making doors / irrigable field (second two forms listed) | toḍabla[135] / taġult / tiġula[162] ("elm") | ulmu[134] | ulmus | úlimu / úlumu / urmu | olmo | olmu | urmu | |

| stove / cooker | θafkunt[100] | *focone(?) <focus ("fire"; "fireplace"; "hearth"; "coalpan") | fogu / focu ("fire") | fuoco ("fire") | focu ("fire") | focu ("fire") | ||

| rope | θasuχa[142] | soca | soga | soga | ||||

| field / garden | urṭu / urti[146] | hortus ("garden") | oltu / ortu / otu ("vegetable garden") | orto ("vegetable garden") | ortu ("garden") | ortu ("vegetable garden") | ||

| white mustard (Sinapis arvensis) | (w)ašnaf / hacenafiṭ / hacenafṭ / wayfes / waifs[51] | senapi(s) / sinapi(s) / senape / sinape(?) | senape | sinapi |

For the other month names, seeBerber calendar.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) | This section mayrequirecleanup to meet Wikipedia'squality standards. The specific problem is:work is an invalid parameter for cite book. Please helpimprove this section if you can.(February 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link){{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)