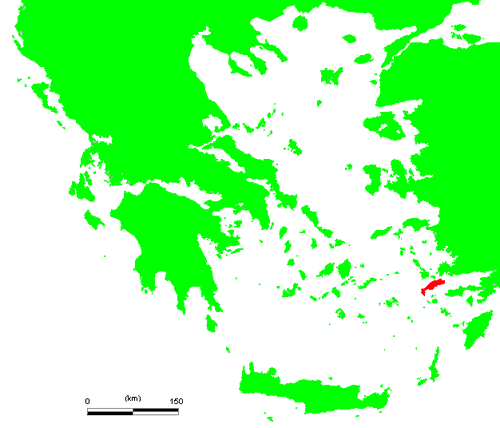

TheMassacre of Kos (Italian:Eccidio di Kos) was awar crime perpetrated in early October 1943 by theWehrmacht againstItalian armyPOWs on theDodecanese island ofKos, then underItalian occupation. About a hundred Italian officers were shot on the commands of GeneralFriedrich-Wilhelm Müller, after being considered traitors for resisting theGerman invasion of the island (known as theBattle of Kos, part of theDodecanese campaign).[1][2]

Background

editKos was occupied by Italy since theItalo-Turkish War of 1912, which ended the longOttoman rule over the island. In the course of theSecond World War, Kos became important because of an airfield nearAntimachia. Thearmistice of Cassibile on 8 September 1943, which stipulated the surrender ofItaly to theAllies, was greeted with enthusiasm both by the Italian army and the local population in the hope of an imminent conclusion of the war. The few Germans on the island were caught off guard and easily disarmed. Soon after, more than 1,500 British troops landed on Kos to assist the approximately 4,000 Italian soldiers in defending the island from a possible German invasion.

In the dawn of 3 October, the German22nd Air Landing Division (then stationed onCrete), led by General Friedrich-Wilhelm Müller, began OperationPolar Bear by landing in three different locations on the island, both from the sea and the air. During the battle there was no coordination between the Italians and the British, theRAF was unable to provide air cover, and the lack of sufficient anti-aircraft artillery allowed theLuftwaffe'sFliegerkorps X to carry out heavy air bombardments undisturbed. Thus, even though the ground forces defending Kos vastly outnumbered the Germans (about 5,500 English and Italians vs. approximately 1,000 Germans), they surrendered on October 4. A total of 1,388 British and 3,145 Italians were captured and mustered inNeratzia Castle in the city of Kos.

The massacre

editBetween 4 and 6 October, 148 captured Italian officers (who belonged to the 10th Regiment,50th Infantry DivisionRegina, commanded by Colonel Felice Leggio) underwent a summary trial ordered by Müller. It was concluded that all the officers who had remained loyal to KingVittorio Emanuele III and had resisted the Germans as a result, were to be shot. Eventually, of the 148 officers, seven switched sides joining the Germans, 28 managed to escape to Turkey, 10 were hospitalized and later transferred tocamps in Germany, whereas the remaining 103 were shot by Müller's men between the evening of October 4 and 7 near theTigaki salt lake (Alyki).[1][page needed][2][page needed]

Aftermath

editIn February 1945, 66 bodies were exhumed from eight mass graves nearLinopotis and buried in the Catholic cemetery of Kos. In 1954, these bodies were transported to Italy and buried in aWW II memorial in Bari. Despite the fact that many bodies were still missing in Kos, no research campaign to locate them was undertaken until 2015. Then, a group of Greek and Italian volunteers carried out excavations which unearthed human remains and personal objects. The recovered remains were placed in a marble urn at theossuary of the Catholic cemetery of Kos.[3]

After the end of the war General Müller was captured in East Prussia by theRed Army and extradited to Greece, where he was sentenced to death by a military court for retaliatory atrocities against civilians inCrete (but not for the events on Kos). He was executed by firing squad inAthens on 20 May 1947 and was the only one punlished among those responsible for the massacre.[4]

The armoire of shame

editIn 1994, during the trial of formerSSErich Priebke, documents related to the Kos massacre were uncovered among many other files in an archive found in a wooden cabinet facing a wall (thearmoire of shame) in thechancellery of the military attorney's office in Rome.[5] In 2003, inquiries by a parliamentary commission revealed that in January 1960, the Italian military attorney general Gen. Enrico Santacroce had signed a filing order for almost 2,000Nazi war crime files.[5][6] In the context of theCold War era, the military attorney general was under strong political pressure to cover up the material by ministersG. Martino andP. Taviani who feared that Germany, Italy'sNATO ally, would be offended.[5]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^abInsolvibile, Isabella (2010).Kos 1943-1948: La strage, la storia. Napoli: Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane.ISBN 978-88-495-2082-8.

- ^abLiuzzi, Pietro Giovanni; Silvestri, Stefano (2015).Kos. Una tragedia dimenticata. Aracne.ISBN 978-88-548-4047-8.

- ^"Comitato Caduti di Kos - Operazione Lisia 1 - 8 luglio 2015".YouTube. 24 July 2015. Retrieved16 May 2020.

- ^"History of the United Nations War Crimes Commission and the Development of the Laws of War. United Nations War Crimes Commission. London: HMSO, 1948". Archived fromthe original on 2012-04-01. Retrieved16 May 2020.

- ^abcVespa, Bruno (2010).Vincitori e vinti. Mondadori.ISBN 978-88-520-1191-7.

- ^Sica, Emanuele; Carrier, Richard (2018).Italy and the Second World War: Alternative Perspectives. History of Warfare. Brill.ISBN 978-900-436-3762.

External links

edit- L'eccidio di Kos, ottobre 1943. Un buon libro su una tragedia dimenticata e qualche appunto su una vicenda minore, Giorgio Rochat, Istituto piemontese per la storia della Resistenza e della società contemporanea; archivedhere.

- L’eccidio di Kos, la piccola Cefalonia "dimenticata": così 103 ufficiali italiani vennero trucidati dai tedeschi, Silvia Morosi and Paolo Rastelli, Corriere della Sera, 8 December 2017; archivedhere.

36°47′27″N27°04′16″E / 36.7909°N 27.0712°E /36.7909; 27.0712