- Feature Paper

- Review

31 October 2025

The Role of Digital Payment Technologies in Promoting Financial Inclusion: A Systematic Literature Review

and

1

Department of Economics, College of Business, Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU), Riyadh 11432, Saudi Arabia

2

Department of Economics, Faculty of Arts, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB T6G 2H4, Canada

*

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

Abstract

In this study, we review recent research on how digital payment technologies (DPTs) promote financial inclusion (FI) across the world. Drawing on empirical studies from the past decade, we show that digital payment systems have helped reduce financial exclusion—particularly in developing economies—by expanding access to essential financial services for underserved groups. The paper also highlights the role of demographic factors such as age and gender, with evidence of higher adoption among youth and women. We identify the main indicators used to measure digital payment adoption and FI, providing a foundation for future empirical analysis. To deepen understanding, we call for combining macroeconomic data with rigorous econometric approaches to better capture how DPTs contribute to inclusive financial systems. The paper further discusses how emerging innovations—including blockchain, artificial intelligence, cloud computing, and biometric authentication—are improving the efficiency, security, and accessibility of digital payments. Together, these technologies are likely to accelerate the transition toward fully digital financial ecosystems and expand the potential for inclusive and sustainable growth.

Keywords:

digital payment technology;financial inclusion;FinTech;mobile payment;payment;blockchain payments;systematic reviewJEL Classification:

G20; O33; E42; G21; O161. Introduction

Digital technologies have transformed nearly every sector of modern economies, from communications and healthcare to education, business, and finance. They have reshaped how people connect, transact, and access essential services, creating major gains in efficiency, access, and convenience [1]. Empirical evidence from developing economies also supports the positive link between digital readiness and economic performance [2]. At the center of this transformation is money and the systems that move it. Traditionally, money has served as a medium of exchange, a store of value, and a unit of account, with payment systems ensuring its circulation. The rise of financial technology (FinTech), however, has changed this landscape, giving rise to digital payment technologies (DPTs) that speed up and expand financial transactions while improving accessibility [3].

Digital payments refer to the use of computers or mobile devices to purchase goods or services, whether through apps, websites, or in-store terminals [4]. Their flexibility allows for transactions across many platforms, making them central to the global financial system. More importantly, they are now viewed as key tools for promoting financial inclusion (FI)—especially in countries where traditional banking is out of reach. By allowing people to open accounts, transfer funds, and manage savings remotely, DPTs make financial services more affordable and accessible [5,6].

The rapid spread of mobile technology has been a driving force behind this change. Mobile phones and expanding internet access have made it possible to reach communities that banks often overlook, including rural areas. This shift has also been transformative for groups that are typically excluded from formal finance. Digital channels provide safer and more transparent ways to send and receive money, lowering costs for users and improving efficiency for governments and businesses alike. As a result, digital payments are helping build more inclusive economies by broadening access to savings, credit, and insurance [7,8].

Major international organizations have recognized the growing role of digital payment systems. The Bank for International Settlements considers them essential for expanding financial access and maintaining economic stability. Similarly, the World Bank and G20 highlight their importance through global initiatives that promote affordable, accessible, and secure digital financial systems [9,10].

Despite these advances, research on DPTs still faces key limitations. Many studies remain conceptual or descriptive, focusing on drivers and barriers rather than measurable outcomes. Empirical analyses—especially those using macroeconomic or long-term data—are still scarce. This is particularly evident in developing regions, where data availability is limited and findings are often based on small-scale surveys. As a result, we lack a clear, evidence-based understanding of how DPTs actually shape FI.

This paper seeks to address that gap through a systematic review of 37 empirical studies published between 2016 and 2025. It organizes and analyzes existing evidence to clarify how DPTs contribute to FI in different socio-economic contexts. The review also identifies the key variables used to measure both digital payment adoption and inclusion—such as account ownership, frequency of use, and access to credit or savings. By bringing these studies together under common themes—regional context, technology type, and policy environment—it provides a clearer picture of what we know and what remains unexplored.

The selected regions—Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA)—represent diverse levels of digital maturity and institutional capacity. This diversity helps reveal how context shapes the success of digital finance. The ultimate goal is to support the development of financial systems that are scalable, sustainable, and responsive to the needs of underserved populations.

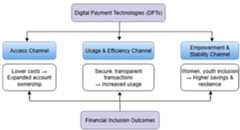

The link between DPTs and FI can be understood through three major channels [11,12]. First, DPTs expand access by lowering transaction costs for the unbanked. Second, they improve usage and efficiency by making money transfers simpler, safer, and faster. Third, they strengthen financial stability by helping households manage income and savings more effectively. These channels interact with broader enabling factors—such as digital infrastructure, financial literacy, and regulation—to shape inclusion outcomes. A conceptual map inFigure 1 illustrates these relationships.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework linking digital payment technologies to financial inclusion outcomes. Source: Authors’ compilation based on reviewed literature (2016–2025).

This review contributes to the extant literature by examining 37 empirical studies covering both developed and developing economies. Through structured synthesis, it compares evidence across contexts and technologies, linking innovations like blockchain, e-wallets, mobile money, and AI to measurable indicators of inclusion. The review also offers a policy-oriented perspective, emphasizing how digital payment ecosystems can grow sustainably across different income levels. This integrated approach builds a stronger empirical foundation for inclusive finance and sets the review apart from previous studies in both scope and policy relevance.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows.Section 2 explains the methodology of the systematic review, including the databases, keywords, and screening steps.Section 3 summarizes the findings from 31 studies across themes such as region, technology, and policy environment.Section 4 discusses methodological approaches and includes six supporting studies that examine determinants of DPTs.Section 5 integrates the results, comparing evidence and outlining policy insights.Section 6 addresses key limitations and future research directions.Section 7 explores broader data and methodological challenges, andSection 8 concludes with policy recommendations for building inclusive and scalable digital finance systems.

2. Methodology

This study employs a Systematic Literature Review (SLR) to evaluate the empirical evidence on the role of DPTs in promoting FI. A systematic approach was chosen to ensure transparency, replicability, and comprehensiveness in identifying relevant studies, following the PRISMA guidelines [13]. The review covers the period 2016–2025, during which digital payment technologies advanced rapidly and scholarly interest in their role in FI intensified.

While digital payment acceptance is usually proxied by mobile money and e-wallet transactions, card payments, and Internet or mobile banking usage, most research evaluates FI by account ownership, usage frequency, and access to credit or savings. The empirical foundation for coding and theme analysis was formed by combining these indicators, which were previously categorised under “Core Indicators and Variables”.

2.1. Search Strategy and Study Selection

The search was conducted across leading academic databases, namely Web of Science (WoS), Scopus, and Google Scholar. These were chosen to include both well-known journals and new research. To capture the wide scope of digital payments, we used a comprehensive list of keywords, including Digital Payments, E-payments, Online Payments, Digital Payment Technologies, Blockchain Payments, Mobile Payments, Mobile Banking, Near Field Communication (NFC), E-wallets, FinTech, QR Code Payments, and Financial Inclusion.

The keywords were mixed using AND and OR to find all possible studies. For example, “Digital Payments AND Financial Inclusion”, “Blockchain OR Mobile Money AND Access to Finance”. This helped collect all studies related to how digital payments support FI.

Outcomes were filtered to cover only peer-reviewed journal articles published in English between 2016 and 2025. Duplicate records were removed manually through DOI matching and cross-database comparison in Excel. Relevance was assessed through a three-step screening—title, abstract, and full-text review—ensuring that only studies with clear empirical focus on DPT–FI relationships were kept for analysis.

This keyword strategy was designed to include studies on both traditional digital channels (e.g., online banking, card payments) and innovative technologies (e.g., blockchain, biometrics, mobile wallets).

The selection of studies followed clear inclusion and exclusion criteria. Only peer-reviewed journal articles or conference papers published in English between 2016 and 2025 were considered. These studies had to examine either the role of DPTs in promoting FI or the key factors influencing digital adoption. Non-peer-reviewed materials, reports, commentaries, and duplicate records were excluded from the review to ensure the reliability and consistency of the evidence base.

Aside from the peer-reviewed empirical research papers on which this review is based, few grey literature sources, including reports and policy briefs from institutions such as the [7,10,14], were accessed. These sources were merely used to provide background and a broader understanding of international trends in digital payment ecosystems and policy development. They were not part of the 37 peer-reviewed studies included in the formal review sample or the quantitative synthesis. We made this distinction to keep the analysis methodologically sound and based on peer-reviewed studies, while still acknowledging important institutional viewpoints

The study followed a three-stage screening process in line with PRISMA standards [13]. First, titles were reviewed to remove articles that were clearly unrelated based on their keywords and scope. Next, abstracts were examined to ensure that each study aligned with the research objectives. Finally, full-text reviews were conducted to extract key data and assess the methodological rigor of the remaining studies.

The initial search across all databases recovered 426 records, including duplicates. After removing duplicates and applying title and abstract screening, 112 papers were kept for full-text review. From an initial pool of articles, 37 empirical studies met the criteria for inclusion. Of these, 31 studies directly addressed the relationship between DPTs and FI, while six studies examined determinants and categories of DPTs.

Figure 2 summarizes the systematic screening and selection process. It shows that 426 records were initially identified, 347 remained after duplicates were removed, 112 full-text papers were assessed for eligibility, and finally, 37 empirical studies were included in the review—31 focusing on the DPT–FI relationship and 6 on determinants and categories of DPTs.

Figure 2. PRISMA flow diagram for study selection (2016–2025). Source: Authors’ compilation based on PRISMA framework.

Most papers were removed at title and abstract review. This was because the initial search contained many topics, and the screening process was used to limit only those studies that were relevant. This screening ensured that the resultant list of articles contained high-quality research studies that were peer-reviewed and of relevance to the study purpose and selection criteria.

The next section explains how the data from these studies were coded and extracted to allow for systematic comparison and clear thematic analysis.

2.2. Data Coding, Handling, and Synthesis

The included studies were coded systematically using an Excel-based framework. Each study was categorized based on:

- Research methodology (survey, econometric model, descriptive/conceptual, case study).

- Geographic focus.

- Type of digital payment technology analyzed (mobile money, internet banking, card payments, e-wallets, blockchain, etc.).

- Key findings and contributions.

We coded all articles via a standardized Excel framework with predefined categories to ensure coding quality and consistency. We then pilot tested the coding process on a subset of ten randomly selected studies to verify inter-coder agreement and category clarity. Any inconsistencies were resolved through iterative refinement of the coding template. This process improved the reliability and transparency of the data extraction procedure and reduced subjective interpretation bias. This coding allowed for systematic comparison across studies and facilitated the thematic review presented inSection 3.

The extracted information from each study—covering variables, methodology, region, and outcomes—was entered into a unified Excel-based matrix. This enabled systematic comparison across studies and facilitated the identification of common FI indicators and their digital payment counterparts. To generate the quantitative summaries presented in the results section, frequency counts were calculated for the direction and strength of relationships (positive, mixed, or insignificant) between DPT adoption and FI variables. The analysis thus combines qualitative interpretation with quantitative aggregation, allowing consistent comparison of findings across regions and methodological designs.

2.3. Quality Evaluation, Bias Consideration, and Methodological Limitations

Each included study underwent a critical assessment of methodological quality. The evaluation considered the study design (survey, econometric, or case-based), sample size adequacy, data source reliability, and clarity of reported outcomes. Studies that lacked methodological transparency or empirical grounding were excluded. To limit bias, only peer-reviewed English-language articles were retained, and duplicate records were removed. Although publication bias cannot be fully ruled out, this systematic quality screening enhances the credibility and consistency of the evidence base.

Although the systematic review methodology is set to ensure transparency and replicability, a number of limitations must be acknowledged. First, only peer-reviewed articles in English language were considered, and it could have omitted some important evidence of non-English studies, governmental publications, or institutional reports in the subject. Second, we excluded the unpublished and grey literature, and this can introduce publication bias of studies with significant or positive results.

Third, the search was mainly based on international academic databases (Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar), which may not fully represent national datasets or policy documents. Such limitations may hinder the understanding and expansion of the evidence base, but they were necessary to guarantee methodological rigor and comparability across studies.

2.4. Scope of Analysis

The analysis is divided into two parts. The first part reviews the 31 studies that directly investigate how DPTs contribute to FI. These studies are organized thematically inSection 3 and listed inTable 1 in chronological order.

Table 1. Studies on Digital Payment Technologies and Financial Inclusion (2016–2025).

The second part examines six studies focusing on determinants and categories of DPTs. Although they do not directly assess FI outcomes, they provide important context on technological innovations, adoption factors, and system evolution. These are summarized in Table 2 and discussed inSection 4.

By structuring the review in this way, the paper captures both the impact of DPTs on FI and the underlying drivers shaping their adoption and development. This structure provides the basis for the thematic review presented inSection 3.

3. Literature Review and Thematic Findings

The 31 studies that we reviewed provide a wide-ranging perspective on how DPTs influence FI. The literature demonstrates that digital payments have become vital in extending financial services to underserved groups, reducing reliance on cash, and promoting economic participation. However, progress is uneven across regions, technologies, and social groups, with significant barriers such as infrastructure gaps, regulatory challenges, and digital illiteracy still impeding full FI. The detailed characteristics and findings of these studies are summarized inTable 1, while the following subsections present a thematic review of their key contributions.

3.1. Regional and Technological Dimensions

Studies from Sub-Saharan Africa [21,27,34] highlight the transformative effect of mobile money in rural and low-income settings, where traditional banking infrastructure remains weak. South Asian studies [35,36] emphasize the role of digital wallets and mobile platforms in bridging the urban–rural gap, though challenges in infrastructure persist. Research from the Middle East and North Africa shows similar trends: Al-Smadi [23] finds that digital finance is closely tied to income and internet penetration, while Al-Mazmoumi [22] underscores how mobile banking strengthens participation in economic activity. In advanced economies, such as the Euro Area, Petrikova & Kocisova [21] highlight demographic drivers like age and gender, reflecting the more nuanced role of digital adoption in developed contexts.

Mobile money, mobile banking, and e-wallets consistently emerge as key enablers of financial access. Han [15] and Bajpai [19] point to their role in empowering individuals who had previously been excluded from formal finance. Kenya’s M-Pesa remains one of the most cited examples of success, revolutionizing the way people save, borrow, and transfer funds [33]. These technologies reduce geographic and social barriers by offering accessible, low-cost, and user-friendly services.

Recent research extends beyond mobile platforms to explore blockchain, artificial intelligence (AI), and cloud computing. Eziamaka et al. [20] show how these technologies enhance scalability and efficiency, while [29] argue that cloud-based platforms lower costs for financial institutions. Blockchain’s capacity to create tamper-proof digital identities and support low-cost cross-border transactions is frequently noted as a promising solution to long-standing barriers in financial access. Similar discussions on the role of digital currencies in promoting FI have also been reported [44]. These findings reinforce the global relevance of digital payment innovations across diverse regulatory contexts.

3.2. Socio-Economic and Demographic Outcomes

In contexts where banking systems are underdeveloped, digital payments often serve as substitutes for formal infrastructure. Oumarou & Celes-tin [31] document how mobile money significantly expanded inclusion in WAEMU countries, while Ekong & Ekong [28] find that Nigeria’s digital currency improved access but still faced rural adoption barriers. Similar findings are reported by [25] for Sub-Saharan Africa, stressing the role of internet connectivity and mobile penetration in expanding financial services.

Several studies link digital payments to broader economic benefits. Al-Mazmoumi [22] finds that mobile banking in Saudi Arabia contributes positively to economic growth, while Arner et al. [32] argue that FinTech enhances sustainability by bridging gaps in financial access. Ugwuanyi et al. [34] show how digital finance in Nigeria supports liquidity and transactional efficiency, further underlining its role as an engine of economic participation.

The reviewed studies generally categorize variables such as age, gender, and income based on survey data or national FI datasets. Age is often divided into cohorts (e.g., 18–25, 26–35, 36–46), gender is measured in terms of binary self-identification (male/female), and income is measured by quantiles or income scales. These variables are systematically connected to the results of digital payment, including account ownership, frequency of transactions, and the use of mobile or e-wallet services, to determine the difference in patterns of inclusions between demographic groups.

Han [15] and Dixit & Sharma [18] show that women benefit disproportionately from mobile payments, gaining secure and confidential access to financial services. Youth populations, especially those aged 26–35, are also more likely to adopt digital-first solutions [18]. These demographic insights highlight how digital finance can reduce inequalities in access, particularly for women and younger cohorts.

Despite substantial progress in the use of digital payments, challenges remain. Dixit & Sharma [18] point to low levels of digital literacy and rural infrastructure as major barriers in India. Refs. [12,35] highlight similar issues in emerging markets, with concerns around cybersecurity, trust in platforms, and affordability acting as further impediments. These studies underscore that the expansion of digital finance is not automatic but depends on supportive ecosystems.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the resilience of digital payments in maintaining financial flows during systemic shocks [21,38]. Lastly, favorable policy environments are finally what make digital payments successful. According to [30,35] lasting digital FI requires clear and fair regulations, secure data protection, and strong digital infrastructure that people can trust and use easily.

These thematic findings offer the analytical basis to the following section that analyzes the methodological standpoints of the reviewed literature.

4. Methodological Approaches in the Literature

The 37 studies reviewed employ a diverse range of methodologies, reflecting both the breadth of research interest and the varying availability of data across regions. The majority of studies rely on survey-based methods and descriptive analyses, which provide valuable micro-level insights but often lack generalizability. A smaller set of studies apply econometric approaches, using cross-sectional or panel data to test the determinants and outcomes of digital payment technologies (e.g., [35,37]). Case studies and conceptual analyses are also common, particularly in developing regions where reliable datasets remain scarce.

This methodological imbalance suggests that, while the field has grown rapidly, it remains dominated by exploratory and descriptive research. Few studies use advanced econometric techniques or rich macroeconomic data, limiting the ability to establish causal relationships and broader policy relevance. This highlights an important gap for future scholarship: the need to combine large-scale data sources with robust econometric models to capture the nuanced role of digital payments in promoting FI.

The key determinants and categories of DPTs identified in the six supporting studies are summarized inTable 2. These studies do not directly measure FI outcomes but provide important insights into the drivers of adoption, including technological innovations, institutional frameworks, and user behavior.

Table 2. Determinants and Categories of Digital Payment Technologies.

Table 2. Determinants and Categories of Digital Payment Technologies.

| Study | Focus/Findings | Main Determinants of Digital Payment Technologies |

|---|---|---|

| Polasik et al. [6] | Technological innovations in payment systems offer faster, secure, and convenient payment options, enhancing access to digital payments and promoting FI. |

|

| Anton & Nucu [45] | Impact of traditional and digital FI on banking stability across 81 countries, showing that digital payment systems support financial stability, a key factor for FI. |

|

| Chauhan & Sharma [46] | Review of emerging digital payment technologies, global research trends, and theoretical frameworks, highlighting transformative effects of digital payments. |

|

| Teker et al. [8] | Systematic literature review categorizing types of digital payment technologies, identifying card and mobile payments as most influential in driving FI in emerging markets. |

|

| Teker et al. [47] | Evolution of digital payment systems, categorizing them into five types, showing a broad range of innovations in digital transactions. |

|

| Bezhovski [48] | Evaluation of global growth of mobile and electronic payment systems, categorizing payment methods, which enhance the accessibility of digital payments. |

|

Source: Authors’ compilation.

5. Results and Discussion

Our review of 37 studies shows a clear agreement that DPTs play a growing role in improving FI. Although this review does not calculate exact effect sizes like a meta-analysis, it summarizes the main findings to show overall trends. We created a simple quantitative summary using the coded results of the studies.Table 3 presents the overall effect patterns and regional distribution. This helps translate descriptive findings into measurable comparative insights.

Table 3. Quantitative summary of effects and regional distribution (2016–2025).

Table 3 underlines both the strength of the overall relationship and the uneven regional representation, setting a clearer analytical basis for our discussion that follows.

The framework also displays causal processes between DPTs and the outcomes of FI. DPTs reduce transaction and entry costs, allow access by previously unbanked customers (access channel); boost efficiency, trust and frequency of utilization of financial services (usage channel); and boost economic access and resilience to women and low-income populations (empowerment channel). These processes justify the presence of greater effects in economies that have more ready digital infrastructure, regulatory preparedness and increased mobile penetration (seeFigure 1).

We also observed that some significant disparities tend to arise between the stated goals and the results of the studies. Several articles sought to determine the determinants of FI, but the primary data used was descriptive statistics that do not offer much power to explain the results. Still others attempted to test technologies or policy frameworks without considering contextual or behavioral impacts to adoption. Also, even though most studies had the goal of testing causality, data and methodological constraints often restricted the scope to correlational analysis. The awareness of these gaps highlights the necessity of further studies in the future to match these goals with the right data and analytical instruments that will generate evidence more suitable to policy.

5.1. Regional and Technological Evidence

The evidence demonstrates strong regional differences in the relationship between digital payments and FI. In Sub-Saharan Africa, mobile money services such as M-Pesa have revolutionized financial access, particularly in rural areas [27,33]. In South Asia, adoption has been widespread, but persistent infrastructure gaps limit rural outreach [35,36]. In MENA, digital banking adoption is closely tied to income and internet penetration [23], while Saudi Arabia shows strong evidence that mobile banking supports economic growth and participation [22,49]. In contrast, studies from Europe and North America focus more on demographic trends, such as higher adoption among women and younger populations [17,21].

Mobile money, e-wallets, and mobile banking dominate the literature as proven drivers of inclusion, but recent studies point to new technological frontiers. Blockchain offers secure digital identities and low-cost cross-border transfers [20,37], cloud computing improves scalability for financial institutions [29], and artificial intelligence is increasingly used to personalize financial services and extend credit access to underserved groups [20]. These innovations are expected to complement traditional mobile money services, though their adoption remains uneven, particularly in developing economies.

5.2. Socio-Economic, Structural, and Contextual Outcomes

The studies reviewed show a clear and consistent relationship between DPT and positive socio-economic outcomes. Research from Africa, Asia and MENA confirms that DPT helps people—especially low-income people—gain better access to savings, credit and insurance [25,31]. Women and youth emerge as the main beneficiaries [21,24], while evidence from Saudi Arabia and Nigeria shows that digital finance supports economic growth, liquidity and efficiency [22,34]. Together, these results show that DPTs are not only tools for inclusion—they also drive macroeconomic growth.

However, structural barriers still exist. Many people lack digital skills, Internet access is weak, and social norms—especially regarding gender—still limit who can benefit. In countries with fragile institutions, these barriers are even stronger. Therefore, technology is not enough—real change happens when it comes with social support and good institutions.

Though most studies have found a positive correlation between DPT and FI, the evidence quality is not uniform. Most rely on descriptive or cross-sectional data that cannot determine causality, with fewer using econometric methods that provide credible findings. Heterogeneity in measurement of FI and digital adoption also makes comparison challenging.

These findings should be interpreted carefully, as they highlight general patterns rather than absolute conclusions. Cultural and institutional contexts remain central to understanding how digital inclusion evolves. People’s trust in financial systems, the consistency of regulations, and the overall social environment all influence how quickly digital technologies are adopted. In this sense, the success of digital payment systems depends not only on technology itself but also on the economic and institutional realities that shape everyday life.

5.3. Barriers, Resilience, and Policy Implications

Despite encouraging progress, several studies identify structural barriers that restrict the full potential of digital payments. Low levels of digital literacy, weak infrastructure, and affordability remain persistent problems in developing economies [12,18]. Cybersecurity concerns and lack of trust in platforms also limit adoption [35]. Some contradictory evidence also emerges. For instance, while many African studies highlight transformative impacts, others argue that digital technologies alone are insufficient to overcome structural inequalities [42]. These inconsistencies suggest that while digital payments can reduce barriers, they are not a universal solution and must be embedded within broader socio-economic development strategies.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the resilience of digital payments in maintaining financial flows during systemic shocks. Petrikova & Kocisova [21] and Soriano [38] find that digital channels allowed governments and organizations to deliver welfare payments and sustain transactions under lockdown conditions. These findings show the importance of digital systems not only for long-term development but also for crisis resilience. This experience reinforces the argument that resilient digital infrastructure forms a cornerstone of economic stability during global disruptions.

Overall, the literature demonstrates that DPTs significantly advance FI by expanding access, lowering costs, and improving efficiency. However, the impact is uneven, shaped by local infrastructure, regulatory frameworks, and demographic factors. The dominance of survey-based and descriptive studies highlights the need for more rigorous econometric analysis and macro-level data to fully capture the causal pathways linking digital payments to FI. For policymakers, the evidence underscores that technology alone is not enough; enabling environments, literacy programs, and targeted interventions remain essential to ensure that digital finance benefits the most vulnerable groups. Taken together, these findings point to the structural constraints that limit the development of digital payment ecosystems across different income groups.

To further contextualize these findings,Table 4 summarizes the dominant evidence patterns and their corresponding policy implications across different income groups.

Table 4. Summary of evidence patterns and policy implications by income group.

Table 4 gives a summary of the variations in the relationship between DPTs and FI between income groups, which connects the empirical data to the policy priorities which are specific to the context.

6. Limitations of the Review

This review has several limitations that arise from the scope of available evidence and the methodological boundaries of the analysis. First, many of the studies are descriptive or based on small samples, making it difficult to draw firm conclusions or generalize findings to broader contexts. Second, there is considerable variation in how studies measure key concepts. For instance, indicators used to capture digital payment usage or FI often differ, limiting comparability across datasets. Third, our review focuses on literature published between 2016 and 2025 and includes only English-language, peer-reviewed studies. While this improves reliability and ensures methodological rigor, it also means that potentially valuable insights from government reports, non-English sources, or studies reporting neutral or non-significant results may have been overlooked.

Among these limitations, data quality and methodological inconsistencies have the greatest influence on the certainty of our conclusions. Conceptual and contextual gaps also play a moderate role, reflecting differences in national priorities and institutional contexts. In contrast, biases such as language or publication selection appear to have less impact on the direction of findings, though they may still reduce the overall comprehensiveness of the review.

7. Broader Research and Data Challenges

Beyond the immediate limitations of this review, the broader field still faces deeper challenges that shape how research on digital inclusion can move forward. These challenges are not only technical but also methodological, and they influence how well future studies can turn big ideas about inclusion into something measurable and meaningful.

One of the main problems is the lack of reliable and detailed data, especially in low-income and developing countries. Information about how people actually use digital payments—like NFC transactions, QR codes, or mobile wallets—is often missing or inconsistent. Even basic indicators of FI, such as those divided by gender, region, or income, are patchy or incomplete. Without this kind of data, it’s difficult to understand how digital adoption spreads, where it slows down, or how it differs between countries with different social and regulatory systems.

Another challenge lies in how researchers choose and define their variables. Many studies focus on what’s easy to measure—such as the number of transactions or how often people use digital tools—while leaving out more complex factors that may matter just as much. For example, service disruptions, user safety, data privacy, or long-term effects like resilience to income shocks are often ignored. By focusing only on access or use, studies can create an unrealistically positive image of digital inclusion.

Establishing causality is still a challenge for researchers. Countries with stronger institutions or better infrastructure tend to adopt digital systems first, but these same conditions also make development easier. Because the two go hand in hand, it’s hard to tell how much of the progress comes from digitalization itself versus the advantages that existed beforehand. Future research should address causality and reverse-causality. Suggested strategies include the use of natural experiments, instrumental variables, and difference-in-differences designs to better identify causal effects.

Finally, research on regulation and institutions is often too broad to capture what’s really going on. Studies that rely on big indices—like “Ease of Doing Business” or “Digital Readiness”—miss important details such as enforcement strength, interoperability, or data governance. Building indicators that reflect local realities would make future studies more accurate and comparable across countries.

All these point to the need for research that goes deeper and lasts longer—studies that invest in high-quality data, include multiple dimensions of inclusion, and use strong identification methods. With that kind of evidence, we can better understand how digital payments help build fairer and more resilient financial systems.

8. Conclusions and Policy Implications

In this review, we examined 37 studies published between 2016 and 2025 on how DPTs support FI. The evidence is clear—tools such as mobile money, e-wallets, blockchain, and artificial intelligence are bringing financial services to more people, especially in areas where traditional banks are hard to reach. In regions like Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, mobile payments have had a particularly strong impact. Across all regions, women, young people, and low-income families benefit the most, showing that digital payments can make finance more inclusive and accessible for everyone.

But we also saw that big challenges still exist. Many people don’t have the skills, internet, or trust to use digital tools easily. Weak infrastructure, high costs, and unclear rules still hold things back. Most studies we looked at rely on short-term surveys or basic data, so it’s still hard to tell exactly how digital payments cause long-term change. From all this, we learned that technology alone isn’t enough. To make real progress, governments need to invest in better internet and mobile networks and help people learn how to use financial apps safely. It’s also important to have clear, flexible rules that protect users —things like easy KYC steps, strong data privacy, and fair digital laws. Finally, working together matters—when governments, banks, and telecom companies join forces, and when special support goes to women and low-income groups, digital finance can truly make life better for everyone.

To ensure contextual relevance, policy recommendations should be differentiated by income level. In low-income economies, the priority is coverage: expand mobile networks, grow agent points, and raise digital literacy, with a focus on women and rural areas. In middle-income settings, push interoperability, bring SMEs onto platforms, and link payments to affordable credit to sustain use. In high-income economies, where systems are mature, keep the balance right—robust cybersecurity and consumer protection alongside room for innovation.

Each policy recommendation can be linked to measurable indicators. Progress in digital infrastructure can be tracked through broadband penetration, mobile connectivity, and transaction security. Interoperability can be seen in how often people make payments across different digital platforms, while agent network strength depends on how many active agents serve each community.

The efficiency of ID and KYC procedures shows how easy it is for users to become members of the system, and security and consumer protection can be assessed by how frequently fraud or data issues are discussed. Monitoring such indicators enables policymakers to know what’s working, detect issues early, and refine their strategies accordingly.

Our findings align with the conceptual framework outlined earlier, confirming three main channels through which DPTs foster FI. First, DPTs lower transaction and entry costs, making financial services more accessible to previously excluded populations. Second, they enhance efficiency and trust, encouraging more frequent and sustained use. Finally, DPTs empower marginalized groups—particularly women and low-income households—by helping them build financial resilience and accumulate savings.

Policy design should also reflect demographic and regional diversity. For women, policies should strengthen digital identity, privacy protection, and access to microcredit through mobile platforms. For youth, promoting digital skills and entrepreneurship-based payment systems can ensure long-term engagement. For low-income and rural populations, expanding agent networks and offline payment options can overcome connectivity gaps and affordability barriers. Tailored, context-specific strategies are essential—“one-size-fits-all” approaches rarely succeed.

The resilience of digital payments during crises such as COVID-19 also underlines their broader role in economic recovery. Integrating digital finance into social protection and fiscal policies can strengthen economic stability and inclusion in the long run.

We contribute to the literature by connecting individual adoption patterns with systemic policy outcomes through a unified analytical lens. It also identifies structural and methodological challenges that still constrain causal interpretation. By drawing from cross-regional experiences, this review builds a stronger empirical foundation for future quantitative modeling and offers practical insights for designing inclusive and resilient digital financial ecosystems.

Finally, technology alone cannot resolve deep-rooted structural issues such as poor infrastructure, uneven data coverage, or limited institutional capacity. Sustainable progress requires coordinated institutional efforts to improve data quality, enhance regulatory frameworks, and address the socio-economic foundations of exclusion. Overall, continuous, evidence-driven strategies remain essential to ensure that digital transformation advances inclusion without leaving vulnerable groups behind.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.S. and M.F.S.; methodology, A.M.S. and M.F.S.; software, A.M.S.; validation, A.M.S. and M.F.S.; formal analysis, A.M.S.; investigation, A.M.S. and M.F.S.; resources, A.M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.S. and M.F.S.; writing—review and editing, A.M.S. and M.F.S.; visualization, A.M.S. and M.F.S.; supervision, A.M.S.; project administration, A.M.S.; funding acquisition, A.M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2504).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the Academic Editor and the anonymous reviewers for their insightful feedback and thoughtful suggestions, which have greatly enhanced the quality and clarity of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following list is a summary of all abbreviations and acronyms used in the paper.

| Abbreviation | Full Term | Description/Context of Use |

| DFS | Digital Financial Services | Technology-enabled financial services, including mobile banking, e-wallets, and online payment systems. |

| DPTs | Digital Payment Technologies | Core focus of this paper; includes mobile money, e-wallets, card, blockchain, and AI-driven payment systems. |

| FI | Financial Inclusion | Ensuring access to affordable and useful financial products and services for all individuals and firms. |

| FinTech | Financial Technology | General term describing technology-based innovations in financial services. |

| KYC | Know Your Customer | Regulatory requirement for verifying customer identity in financial institutions. |

| MENA | Middle East and North Africa | Regional classification used for comparative analysis of FI. |

| NFC | Near Field Communication | Short-range wireless technology enabling contactless digital payments. |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses | Framework guiding systematic review transparency and reporting. |

| SMEs | Small and Medium Enterprises | Business segment commonly addressed in digital FI programs. |

| WAEMU | West African Economic and Monetary Union | Regional bloc frequently examined in African FI studies. |

| WoS | Web of Science | Major academic database used for identifying peer-reviewed studies. |

References

- World Bank. Global Digitalization in 10 Charts. 2024. Available online:https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/immersive-story/2024/03/05/global-digitalization-in-10-charts?cid=ECR_LI_worldbank_EN_EXT (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Shahen, A.M.; Sharaf, M.F. Investigating the Relationship Between Digital Technology Readiness and Economic Growth in Egypt During the Period 1985–2019 An Analytic and Econometric Approach.Egypt. J. Dev. Plan.2021,29, 11–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodgson, M.; Gann, D.; Wladwsky-Berger, I.; Sultan, N.; George, G. Managing Digital Money.Acad. Manag. J.2015,58, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey. Consumer Digital Payments: Already Mainstream, Increasingly Embedded, Still Evolving. 2024. Available online:https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/financial-services/our-insights/banking-matters/consumer-digital-payments-already-mainstream-increasingly-embedded-still-evolving (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Bradford, T.; Keeton, W.R. New Person-to-Person Payment Methods: Have Checks Met Their Match?Econ. Rev.2012,97, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Polasik, M.; Górka, J.; Wilczewski, G.; Kunkowski, J.; Przenajkowska, K.; Tetkowska, N.Chronometric Analysis of a Payment Process for Cash, Cards and Mobile Devices; SciTePress: Setubal, Portugal, 2025; pp. 220–229. [Google Scholar]

- Define Digital Payments. Better than Cash Alliance. Available online:https://www.betterthancash.org/define-digital-payments (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Khando, K.; Islam, M.S.; Gao, S. The Emerging Technologies of Digital Payments and Associated Challenges: A Systematic Literature Review.Future Internet2023,15, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Payment Systems.World Bank. Available online:https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/paymentsystemsremittances (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- World Bank. Financial Inclusion; Text/HTML; World Bank. 2025. Available online:https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialinclusion/overview (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Heath, R.; Riley, E. Digital Financial Services and Women’s Empowerment: Experimental Evidence from Tanzania.Indiana J. Econ. Bus. Manag.2024,5, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ozili, P.K. Impact of Digital Finance on Financial Inclusion and Stability.Borsa Istanb. Rev.2018,18, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement.PLoS Med.2009,6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cœuré, B.; Loh, J.Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures—Central Bank Digital Currencies; Bank for International Settlements: Basel, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.Digital Finance and Financial Inclusion in Africa; Korea Institute for International Economic Policy: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2024; pp. 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, K. Digital Financial Inclusion.Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. IJISRT2024,9, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocharive, A.; Iworiso, J. The Impact of Digital Financial Services on Financial Inclusion: A Panel Data Regression Method.Int. J. Data Sci. Anal.2024,10, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, D.K.; Sharma, D.R. The Use of Digital Payment Methods and Its Implications on Financial Inclusion: A Survey Study.Eur. Econ. Lett.2024,14, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, D.A.B. How Digital Finance and Fintech Can Improve Financial Inclusion?Int. J. Adv. Res. Sci. Commun. Technol.2024,4, 544–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eziamaka, N.V.; Odonkor, T.N.; Akinsulire, A.A. Pioneering Digital Innovation Strategies to Enhance Financial Inclusion and Accessibility.Open Access Res. J. Eng. Technol.2024,7, 043–063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrikova, T.; Kocisova, K. Digital Payments as an Indicator of Financial Inclusion in Euro Area Countries.EM Ekon. Manag.2024,27, 162–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mazmoumi, Y.A.M. Digital Financial Inclusion and Economic Performance in Saudi Arabia.Arab. J. Lit. Hum. Stud. Arab. Inst. Educ. Sci. Lett. Egypt2024,8, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Smadi, M.O. Examining the Relationship between Digital Finance and Financial Inclusion: Evidence from MENA Countries.Borsa Istanb. Rev.2023,23, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Yajuan, L.; Khan, S. Promoting China’s Inclusive Finance Through Digital Financial Services.Glob. Bus. Rev.2022,23, 984–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasiisii, A.S.; Mariadoss, S.; Golden, S.A.R. The Effectiveness of Digital Financial Inclusion in Improving Financial Capability.Int. J. Prof. Bus. Rev.2023,8, e0839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parameshwari, G.; Lokesha, K. Digital Financial Inclusion in Karnataka: Evaluating the Adoption of Electronic Payments in Social Welfare Schemes.Int. J. Multidiscip. Res.2023,5, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouladoum, J.-C.; Wirajing, M.A.K.; Nchofoung, T.N. Digital Technologies and Financial Inclusion in Sub-Saharan Africa.Telecommun. Policy2022,46, 102387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekong, U.M.; Ekong, C.N. Digital Currency and Financial Inclusion in Nigeria: Lessons for Development.J. Internet Digit. Econ.2022,2, 46–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavlutova, I.; Spilbergs, A.; Verdenhofs, A.; Natrins, A.; Arefjevs, I.; Volkova, T. Digital Transformation as a Driver of the Financial Sector Sustainable Development: An Impact on Financial Inclusion and Operational Efficiency.Sustainability2022,15, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutfi, A.; Al-Okaily, M.; Alshirah, M.H.; Alshira’h, A.F.; Abutaber, T.A.; Almarashdah, M.A. Digital Financial Inclusion Sustainability in Jordanian Context.Sustainability2021,13, 6312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oumarou, I.; Celestin, M. Determinants of Financial Inclusion in West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) Countries.Theor. Econ. Lett.2021,11, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arner, D.W.; Buckley, R.P.; Zetzsche, D.A.; Veidt, R. Sustainability, FinTech and Financial Inclusion.Eur. Bus. Organ. Law Rev.2020,21, 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.H.; Green, C.; Jiang, F. Mobile Money, Financial Inclusion And Development: A Review With Reference To African Experience.J. Econ. Surv.2020,34, 753–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwuanyi, G.; Efanga, U.; Anene, E. Investigating the Impact of Digital Finance on Money Supply in Nigeria.Niger. J. Bank. Financ.2020,12, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar, T. Digital Financial Inclusion: A Payoff of Financial Technology and Digital Finance Uprising in India.Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res.2019,8, 3434–3438. [Google Scholar]

- Durai, T.; Stella, G. Digital Finance and Its Impact on Financial Inclusion.J. Emerg. Technol. Innov. Res.2019,6, 122–127. [Google Scholar]

- Saal, M.; Starnes, S.; Rehermann, T.Digital Financial Services: Challenges and Opportunities for Emerging Market Banks; International Finance Corporation: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, M.A.Factors Driving Financial Inclusion and Financial Performance in Fintech New Ventures: An Empirical Study; Singapore Management University: Singapore, 2017; pp. 1–258. [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh, A.A.; Glavee-Geo, R.; Karjaluoto, H. Exploring the Nexus between Financial Sector Reforms and the Emergence of Digital Banking Culture—Evidences from a Developing Country.Res. Int. Bus. Financ.2017,42, 1030–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyekum, F.; Locke, S.; Hewa-Wellalage, N.Financial Inclusion and Digital Financial Services: Empirical Evidence from Ghana; MPRA Paper; Munich Personal RePEc Archive: Munich, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wyman, O.Accelerating Financial Inclusion in South-East Asia with Digital Finance; Asian Development Bank and Oliver Wyman: Tokyo, Japan, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agufa, M.M. The Effect of Digital Finance on Financial Inclusion in the Banking Industry in Kenya. Master’s Thesis, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 2016. Available online:https://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke/handle/11295/98616 (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Allen, F.; Demirguc-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L.; Martinez Peria, M.S. The Foundations of Financial Inclusion: Understanding Ownership and Use of Formal Accounts.J. Financ. Intermediation2016,27, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahen, A.M.; Sharaf, M.F. Analysis of the Role of Digital Currencies in Enhancing Financial Inclusion: Opportunities and Challenges.J. Fac. Econ. Polit. Sci.2025,26, 7–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, S.; Nucu, A.E.A. The Impact of Digital Finance and Financial Inclusion on Banking Stability: International Evidence.Oeconomia Copernic.2024,15, 563–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, Y.; Sharma, P. A Systematic Literature Review of Digital Payments.Metamorph. J. Manag. Res.2024,23, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teker, S.; Teker, D.; Orman, I. Evolution of Digital Payment Systems and a Breakthrough.J. Econ. Manag. Trade2022,28, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezhovski, Z. The Future of the Mobile Payment as Electronic Payment System.Eur. J. Bus. Manag.2016,8, 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Sharaf, M.F.; Shahen, A.M.; Alharaib, M.A.Digital Financial Inclusion and Socioeconomic Sustainability in Saudi Arabia: Drivers, Disparities, and Policy Pathways; Economic Research Forum (ERF): Cairo, Egypt, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1. Conceptual framework linking digital payment technologies to financial inclusion outcomes. Source: Authors’ compilation based on reviewed literature (2016–2025).

Figure 1. Conceptual framework linking digital payment technologies to financial inclusion outcomes. Source: Authors’ compilation based on reviewed literature (2016–2025).

Figure 2. PRISMA flow diagram for study selection (2016–2025). Source: Authors’ compilation based on PRISMA framework.

Figure 2. PRISMA flow diagram for study selection (2016–2025). Source: Authors’ compilation based on PRISMA framework.

Table 1. Studies on Digital Payment Technologies and Financial Inclusion (2016–2025).

Table 1. Studies on Digital Payment Technologies and Financial Inclusion (2016–2025).

| Study | Focus Area | Main Contribution/Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Han [15] | Digital Finance in Africa | Mobile money enhances financial access for SMEs and reduces financial exclusion. |

| Kapoor [16] | Digital FI | Mobile banking and card payments foster economic stability and inclusion. |

| Ocharive & Iworiso [17] | DFS in the Americas | Mobile and electronic payments enhance inclusion across North and South America. |

| Dixit & Sharma [18] | Digital Payments in India | Digital payments reduce cash dependency but face rural infrastructure challenges. |

| Bajpai [19] | FinTech and Access | FinTech solutions improve access to financial services for underserved groups. |

| Eziamaka et al. [20] | Tech for Marginalized Groups | AI, blockchain, and cloud tech enhance scalability and financial access. |

| Petrikova & Kocisova [21] | Euro Area Adoption | Younger individuals and women drive adoption post-COVID-19. |

| Al-Mazmoumi [22] | Saudi Digital Finance | Mobile banking empowers economic participation and boosts growth. |

| Al-Smadi [23] | Digital Finance in MENA | Digital finance correlates with income and internet access, improving inclusion. |

| Hasan et al. [24] | DFS in China | DFS bridges the gap for underserved populations and boosts inclusion. |

| Kasiisii et al. [25] | Digital Tech and Inclusion | Tech enables inclusion but faces access and infrastructure challenges. |

| Khando et al. [8] | DPT Categories | Identifies digital payment types influencing inclusion. |

| Parameshwari & Lokesha [26] | Social Welfare in India | E-payments improve efficiency in welfare distribution. |

| Kou-ladoum et al. [27] | Sub-Saharan Africa | Mobile and internet banking increase access in rural areas. |

| Ekong & Ekong [28] | Nigeria’s Digital Currency | Positive impact on inclusion, though rural challenges remain. |

| Mavlutova et al. [29] | EU and Baltic States | Digital payments improve efficiency but face literacy barriers. |

| Lutfi et al. [30] | Mobile Adoption in Jordan | Usefulness and cost drive adoption, boosting inclusion. |

| Oumarou & Celes-tin [31] | WAEMU Region | Mobile money increased inclusion by 50% over a decade. |

| Arner et al. [32] | FinTech and Sustainability | FinTech bridges inclusion gaps in emerging markets. |

| Ahmad et al. [33] | Kenya’s M-Pesa | Mobile money revolutionizes FI and development. |

| Ugwuanyi et al. [34] | Nigeria’s Money Supply | Digital finance supports economic transactions and liquidity. |

| Raviku-mar [35] | FinTech in India | Boosts bank ownership and reduces urban-rural gap. |

| Durai & Stella [36] | Digital Channels | Mobile wallets and cards expand convenience and access. |

| Ozili [12] | Digital Finance Analysis | Increases access but faces rural and cybersecurity issues. |

| Saal et al. [37] | DFS and Banking | Mobile and blockchain tech modernize finance and expand inclusion. |

| Soriano [38] | Tech in Africa and Asia | Digital tools support inclusion in underserved regions. |

| Shaikh et al. [39] | Pakistan’s Banking | Mobile and branchless banking overcome geographic barriers. |

| Agyekum et al. [40] | Ghana Mobile Money | Mobile outperforms banks in fostering inclusion. |

| Wyman, Oliver [41] | SE Asia Digital Finance | Mobile wallets address credit needs for low-income users. |

| Agufa [42] | Kenya Digital Finance | Limited impact of digital tools, other factors matter more. |

| Allen et al. [43] | Global DPT Impact | Digital payments raise account ownership and participation. |

Source: Authors’ compilation.

Table 3. Quantitative summary of effects and regional distribution (2016–2025).

Table 3. Quantitative summary of effects and regional distribution (2016–2025).

| Category | Share of Studies (%) | Key Insight |

|---|---|---|

| Effect strength |

| Most studies confirm a strong positive DPT–FI link |

| Regional distribution |

| Developing-economy evidence dominates the literature |

Source: Authors’ compilation.

Table 4. Summary of evidence patterns and policy implications by income group.

Table 4. Summary of evidence patterns and policy implications by income group.

| Income Group | Main Evidence Pattern | Policy Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Low-income economies |

|

|

| Middle-income economies |

|

|

| High-income economies |

|

|

Source: Authors’ compilation.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Article Metrics

Citations

Article Access Statistics

Multiple requests from the same IP address are counted as one view.