Introducing the scheduler.yield origin trial

Building websites that respond quickly to user input has been one of the most challenging aspects of web performance—one that the Chrome Team has been working hard to help web developers meet. Just this year,it was announced that theInteraction to Next Paint (INP) metric would graduate from experimental to pending status. It is now poised to replaceFirst Input Delay (FID) as a Core Web Vital in March of 2024.

In a continued effort to deliver new APIs that help web developers make their websites as snappy as they can be, the Chrome Team is currently running anorigin trial forscheduler.yield starting in version 115 of Chrome.scheduler.yield is a proposed new addition to the scheduler API that allows for both an easier and better way to yield control back to the main thread thanthe methods that have been traditionally relied upon.

On yielding

JavaScript uses the run-to-completion model to deal with tasks. This means that, when a task runs on the main thread, that task runs as long as necessary in order to complete. Upon a task's completion, control isyielded back to the main thread, which allows the main thread to process the next task in the queue.

Aside from extreme cases when a task never finishes—such as an infinite loop, for example—yielding is an inevitable aspect of JavaScript's task scheduling logic. Itwill happen, it's just a matter ofwhen, and sooner is better than later. When tasks take too long to run—greater than 50 milliseconds, to be exact—they are considered to belong tasks.

Long tasks are a source of poor page responsiveness, because they delay the browser's ability to respond to user input. The more often long tasks occur—and the longer they run—the more likely it is that users may get the impression that the page is sluggish, or even feel that it's altogether broken.

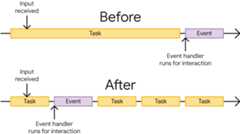

However, just because your code kicks off a task in the browser doesn't mean you have to wait until that task is finished before control is yielded back to the main thread. You can improve responsiveness to user input on a page by yielding explicitly in a task, which breaks the task up to be finished at the next available opportunity. This allows other tasks to get time on the main thread sooner than if they had to wait for long tasks to finish.

When you explicitly yield, you're telling the browser "hey, I understand that the work I'm about to do could take a while, and I don't want you to have to doall of that work before responding to user input or other tasks that might be important, too". It's a valuable tool in a developer's toolbox that can go a long way towards improving the user experience.

The problem with current yielding strategies

Key point: If you're already familiar with current yielding methods—such as usingsetTimeout—you can jumpstraight to the section aboutscheduler.yield.A common method of yieldingusessetTimeout with a timeout value of0. This works because the callback passed tosetTimeout will move the remaining work to a separate task that will be queued for subsequent execution. Rather than waiting for the browser to yield on its own, you're saying "break this big chunk of work up into smaller bits".

However, yielding withsetTimeout carries a potentially undesirable side effect: the work that comesafter the yield point will go to the back of the task queue. Tasks scheduled by user interactions will still go to the front of the queue as they should—but the remaining work you wanted to do after explicitly yielding could end up being further delayed by other tasks from competing sources that were queued ahead of it.

To see this in action, try outthis Codepen demo—or experiment with it in the following embedded version. The demo consists of a few buttons you can click, and a box beneath them that logs when tasks are run. When you land on the page, perform the following actions:

- Click the top button labeledRun tasks periodically, which will schedule blocking tasks to run every so often. When you click this button, the task log will populate with several messages that readRan blocking task with

setInterval. - Next, click the button labeledRun loop, yielding with

setTimeouton each iteration.

You'll notice that the box at the bottom of the demo will read something like this:

Processingloopitem1Processingloopitem2RanblockingtaskviasetIntervalProcessingloopitem3RanblockingtaskviasetIntervalProcessingloopitem4RanblockingtaskviasetIntervalProcessingloopitem5RanblockingtaskviasetIntervalRanblockingtaskviasetIntervalThis output demonstrates the "end of task queue" behavior that occurs when yielding withsetTimeout. The loop that runs processes five items, and yields withsetTimeout after each one has been processed.

This illustrates a common problem on the web: it's not unusual for a script—particularly a third-party script—to register a timer function that runs work on some interval. The "end of task queue" behavior that comes with yielding withsetTimeout means that work from other task sources may get queued ahead of the remaining work that the loop has to do after yielding.

Depending on your application, this may or may not be a desirable outcome—but in many cases, this behavior is why developers may feel reluctant to give up control of the main thread so readily. Yielding is good because user interactions have the opportunity to run sooner, but it also allows other non-user interaction work to get time on the main thread too. It's a real problem—butscheduler.yield can help solve it!

Enterscheduler.yield

scheduler.yield has been available behind a flag as anexperimental web platform feature since version 115 of Chrome. One question you might have is "why do I need a special function to yield whensetTimeout already does it?"

It's worth noting that yielding was not a design goal ofsetTimeout, but rather a nice side effect in scheduling a callback to run at a later point in the future—even with a timeout value of0 specified. What's more important to remember, however, is that yielding withsetTimeout sends remaining work to theback of the task queue. By default,scheduler.yield sends remaining work to thefront of the queue. This means that work you wanted to resume immediately after yielding won't take a back seat to tasks from other sources (with the notable exception of user interactions).

scheduler.yield is a function that yields to the main thread and returns aPromise when called. This means you canawait it in anasync function:

asyncfunctionyieldy(){// Do some work...// ...// Yield!awaitscheduler.yield();// Do some more work...// ...}To seescheduler.yield in action, do the following:

- Navigate to

chrome://flags. - Enable theExperimental Web Platform features experiment. You may have to restart Chrome after doing this.

- Navigate tothe demo page or use the following embedded version of it after this list.

- Click the top button labeledRun tasks periodically.

- Finally, click the button labeledRun loop, yielding with

scheduler.yieldon each iteration.

The output in the box at the bottom of the page will look something like this:

Processingloopitem1Processingloopitem2Processingloopitem3Processingloopitem4Processingloopitem5RanblockingtaskviasetIntervalRanblockingtaskviasetIntervalRanblockingtaskviasetIntervalRanblockingtaskviasetIntervalRanblockingtaskviasetIntervalUnlike the demo that yields usingsetTimeout, you can see that the loop—even though it yields after every iteration—doesn't send the remaining work to the back of the queue, but rather to the front of it. This gives you the best of both worlds: you can yield to improve input responsiveness on your website, but also ensure that the work you wanted to finishafter yielding doesn't get delayed.

scheduler.yield, and is meant to illustrate what benefits it provides by default. However, there are advanced ways of using it, including integration withscheduler.postTask, and the ability to yield with explicit priorities. For more information, read thisin-depth explainer.Give it a try!

Ifscheduler.yield looks interesting to you and you want to try it out, you can do so in two ways starting in version 115 of Chrome:

- If you want to experiment with

scheduler.yieldlocally, type and enterchrome://flagsin Chrome's address bar and selectEnable from the drop-down in theExperimental Web Platform Features section. This will makescheduler.yield(and any other experimental features) available in only your instance of Chrome. - If you want to enable

scheduler.yieldfor real Chromium users on a publicly accessible origin, you'll need to sign up for thescheduler.yieldorigin trial. This lets you safely experiment with proposed features for a given period of time, and gives the Chrome Team valuable insights into how those features are used in the field. For more information on how origin trials work,read this guide.

How you usescheduler.yield—while still supporting browsers that don't implement it—depends on what your goals are. You can usethe official polyfill. The polyfill is useful if the following applies to your situation:

- You're already using

scheduler.postTaskin your application to schedule tasks. - You want to be able to set task and yielding priorities.

- You want to be able to cancel or reprioritize tasks using the

TaskControllerclass thescheduler.postTaskAPI offers.

If this doesn't describe your situation, then the polyfill might not be for you. In that case, you can roll your own fallback in a couple of ways. The first approach usesscheduler.yield if it's available, but falls back tosetTimeout if it isn't:

// A function for shimming scheduler.yield and setTimeout:functionyieldToMain(){// Use scheduler.yield if it exists:if('scheduler'inwindow &&'yield'inscheduler){returnscheduler.yield();}// Fall back to setTimeout:returnnewPromise(resolve=>{setTimeout(resolve,0);});}// Example usage:asyncfunctiondoWork(){// Do some work:// ...awaityieldToMain();// Do some other work:// ...}This can work, but as you might guess, browsers that don't supportscheduler.yield will yield without "front of queue" behavior. If that means you'd rather not yield at all, you can try another approach which usesscheduler.yield if it's available, but won't yield at all if it isn't:

// A function for shimming scheduler.yield with no fallback:functionyieldToMain(){// Use scheduler.yield if it exists:if('scheduler'inwindow &&'yield'inscheduler){returnscheduler.yield();}// Fall back to nothing:return;}// Example usage:asyncfunctiondoWork(){// Do some work:// ...awaityieldToMain();// Do some other work:// ...}scheduler.yield is an exciting addition to the scheduler API—one that will hopefully make it easier for developers to improve responsiveness than current yielding strategies. Ifscheduler.yield seems like a useful API to you, please participate in our research to help improve it, andprovide feedback on how it could be further improved.

Hero image fromUnsplash, byJonathan Allison.

Except as otherwise noted, the content of this page is licensed under theCreative Commons Attribution 4.0 License, and code samples are licensed under theApache 2.0 License. For details, see theGoogle Developers Site Policies. Java is a registered trademark of Oracle and/or its affiliates.

Last updated 2023-08-29 UTC.