Developing RESTful APIs with Python and Flask

Let's learn how to develop RESTful APIs with Python and Flask.

Jan 7, 2025 • 19 min read

Related Tags

Share

Auth0 Marketplace

Discover and enable the integrations you need to solve identity

Explore Auth0 Marketplace

TL;DR: Throughout this article, we will use Flask and Python to develop a RESTful API. We will create an endpoint that returns static data (dictionaries). Afterward, we will create a class with two specializations and a few endpoints to insert and retrieve instances of these classes. Finally, we will look at how to run the API on a Docker container.The final code developed throughout this article is available in this GitHub repository. I hope you enjoy it!

“Flask allows Python developers to create lightweight RESTful APIs.”

Tweet This

Summary

This article is divided into the following sections:

- Why Python?

- Why Flask?

- Bootstrapping a Flask Application

- Creating a RESTful Endpoint with Flask

- Mapping Models with Python Classes

- Serializing and Deserializing Objects with Marshmallow

- Dockerizing Flask Applications

- Securing Python APIs with Auth0

- Next Steps

Why Python?

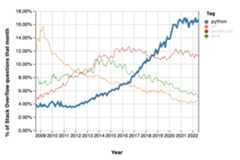

Nowadays, choosing Python to develop applications is becoming a very popular choice.As StackOverflow recently analyzed, Python is one of the fastest-growing programming languages, having surpassed even Java in the number of questions asked on the platform. On GitHub, the language also shows signs of mass adoption, occupying the second position among thetop programming languages in 2021.

The huge community forming around Python is improving every aspect of the language. More and more open source libraries are being released to address many different subjects, likeArtificial Intelligence,Machine Learning, andweb development. Besides the tremendous support provided by the overall community, thePython Software Foundation also provides excellent documentation, where new adopters can learn its essence fast.

Why Flask?

When it comes to web development on Python, there are three predominant frameworks:Django,Flask, and a relatively new playerFastAPI. Django is older, more mature, and a little bit more popular. On GitHub, this framework has around 66k stars, 2.2k contributors, ~350 releases, and more than 25k forks.

FastAPI is growing at high speed, with 48k stars on Github, 370 contributors, and more than 3.9k forks. This elegant framework built for high-performance and fast-to-code APIs is not one to miss.

Flask, although less popular, is not far behind. On GitHub, Flask has almost 60k stars, ~650 contributors, ~23 releases, and nearly 15k forks.

Even though Django is older and has a slightly more extensive community, Flask has its strengths. From the ground up, Flask was built with scalability and simplicity. Flask applications are known for being lightweight, mainly compared to their Django counterparts. Flask developers call it a microframework, where micro (as explained here) means that the goal is to keep the core simple but extensible. Flask won't make many decisions for us, such as what database to use or what template engine to choose. Lastly, Flask hasextensive documentation that addresses everything developers need to start.FastAPI follows a similar "micro" approach to Flask, though it provides more tools like automatic Swagger UI and is an excellent choice for APIs. However, as it is a newer framework, many more resources and libraries are compatible with frameworks like Django and Flask but not with FastAPI.

Being lightweight, easy to adopt, well-documented, and popular, Flask is a good option for developing RESTful APIs.

Bootstrapping a Flask Application

First and foremost, we will need to install some dependencies on our development machine. We will need to installPython 3,Pip (Python Package Index), andFlask.

Installing Python 3

If we are using some recent version of a popular Linux distribution (like Ubuntu) or macOS, we might already have Python 3 installed on our computer. If we are running Windows,we will probably need to install Python 3, as this operating system does not ship with any version.

After installing Python 3 on our machine, we can check that we have everything set up as expected by running the following command:

python --version# Python 3.8.9

Note that the command above might produce a different output when we have a different Python version. What is important is that you are running at leastPython 3.7 or newer. If we get "Python 2" instead, we can try issuingpython3 --version. If this command produces the correct output, we must replace all commands throughout the article to usepython3 instead of justpython.

Installing Pip

Pip is the recommended tool for installing Python packages. While theofficial installation page states thatpip comes installed if we're using Python 2 >=2.7.9 or Python 3 >=3.4, installing Python throughapt on Ubuntu doesn't installpip. Therefore, let's check if we need to installpip separately or already have it.

# we might need to change pip by pip3pip --version# pip 9.0.1 ... (python 3.X)

If the command above produces an output similar topip 9.0.1 ... (python 3.X), then we are good to go. If we getpip 9.0.1 ... (python 2.X), we can try replacingpip withpip3. If we cannot find Pip for Python 3 on our machine, we can follow the instructionshere to install Pip.

Installing Flask

We already know what Flask is and its capabilities. Therefore, let's focus on installing it on our machine and testing to see if we can get a basic Flask application running. The first step is to usepip to install Flask:

# we might need to replace pip with pip3pip install Flask

After installing the package, we will create a file calledhello.py and add five lines of code to it. As we will use this file to check if Flask was correctly installed, we don't need to nest it in a new directory.

# hello.pyfrom flask import Flaskapp = Flask(__name__)@app.route("/")def hello_world(): return "Hello, World!"

These 5 lines of code are everything we need to handle HTTP requests and return a "Hello, World!" message. To run it, we execute the following command:

flask --app hello run * Serving Flask app 'hello' * Debug mode: offWARNING: This is a development server. Do not use it in a production deployment. Use a production WSGI server instead. * Running on http://127.0.0.1:5000Press CTRL+C to quit

On Ubuntu, we might need to edit the

$PATHvariable to be able to run flask directly. To do that, let'stouch ~/.bash_aliasesand thenecho "export PATH=$PATH:~/.local/bin" >> ~/.bash_aliases.

After executing these commands, we can reach our application by opening a browser and navigating tohttp://127.0.0.1:5000/ or by issuingcurl http://127.0.0.1:5000/.

Virtual environments (virtualenv)

Although PyPA—thePython Packaging Authority group—recommendspip as the tool for installing Python packages, we will need to use another package to manage our project's dependencies. It's true thatpip supportspackage management through therequirements.txt file, but the tool lacks some features required on serious projects running on different production and development machines. Among its issues, the ones that cause the most problems are:

pipinstalls packages globally, making it hard to manage multiple versions of the same package on the same machine.requirements.txtneed all dependencies and sub-dependencies listed explicitly, a manual process that is tedious and error-prone.

To solve these issues, we are going to use Pipenv.Pipenv is a dependency manager that isolates projects in private environments, allowing packages to be installed per project. If you're familiar with NPM or Ruby's bundler, it's similar in spirit to those tools.

pip install pipenv

Now, to start creating a serious Flask application, let's create a new directory that will hold our source code. In this article, we will createCashman, a small RESTful API that allows users to manage incomes and expenses. Therefore, we will create a directory calledcashman-flask-project. After that, we will usepipenv to start our project and manage our dependencies.

# create our project directory and move to itmkdir cashman-flask-project && cd cashman-flask-project# use pipenv to create a Python 3 (--three) virtualenv for our projectpipenv --three# install flask a dependency on our projectpipenv install flask

The second command creates our virtual environment, where all our dependencies get installed, and the third will add Flask as our first dependency. If we check our project's directory, we will see two new files:

Pipfilecontains details about our project, such as the Python version and the packages needed.Pipenv.lockcontains precisely what version of each package our project depends on and its transitive dependencies.

Python packages

Like other mainstream programming languages,Python also has the concept of packages to enable developers to organize source code according to subjects/functionalities. Similar to Java packages and C# namespaces, packages in Python are files organized in directories that other Python scripts can import. To create a package in a Python application, we need to create a folder and add an empty file called__init__.py.

Let's create our first package in our application, the main package, with all our RESTful endpoints. Inside the application's directory, let's create another one with the same name,cashman. The rootcashman-flask-project directory created before will hold metadata about our project, like what dependencies it has, while this new one will be our package with our Python scripts.

# create source code's rootmkdir cashman && cd cashman# create an empty __init__.py filetouch __init__.py

Inside the main package, let's create a script calledindex.py. In this script, we will define the first endpoint of our application.

from flask import Flaskapp = Flask(__name__)@app.route("/")def hello_world(): return "Hello, World!"

As in the previous example, our application returns a "Hello, world!" message. We will start improving it in a second, but first, let's create an executable file calledbootstrap.sh in the root directory of our application.

# move to the root directorycd ..# create the filetouch bootstrap.sh# make it executablechmod +x bootstrap.sh

The goal of this file is to facilitate the start-up of our application. Its source code will be the following:

#!/bin/shexport FLASK_APP=./cashman/index.pypipenv run flask --debug run -h 0.0.0.0

The first command defines the main script to be executed by Flask. The second command runs our Flask application in the context of the virtual environment listening to all interfaces on the computer (-h 0.0.0.0).

Note: we are setting flask to run in debug mode to enhance our development experience and activate the hot reload feature, so we don't have to restart the server each time we change the code. If you run Flask in production, we recommend updating these settings for production.

To check that this script is working correctly, we run./bootstrap.sh to get similar results as when executing the "Hello, world!" application.

* Serving Flask app './cashman/index.py' * Debug mode: onWARNING: This is a development server. Do not use it in a production deployment. Use a production WSGI server instead. * Running on all addresses (0.0.0.0) * Running on http://127.0.0.1:5000 * Running on http://192.168.1.207:5000Press CTRL+C to quit

Creating a RESTful Endpoint with Flask

Now that our application is structured, we can start coding some relevant endpoints. As mentioned before, the goal of our application is to help users to manage incomes and expenses. We will begin by defining two endpoints to handle incomes. Let's replace the contents of the./cashman/index.py file with the following:

from flask import Flask, jsonify, requestapp = Flask(__name__)incomes = [ { 'description': 'salary', 'amount': 5000 }]@app.route('/incomes')def get_incomes(): return jsonify(incomes)@app.route('/incomes', methods=['POST'])def add_income(): incomes.append(request.get_json()) return '', 204

Since improving our application, we have removed the endpoint that returned "Hello, world!" to users. In its place, we defined an endpoint to handle HTTPGET requests to return incomes and another endpoint to handle HTTPPOST requests to add new ones. These endpoints are annotated with@app.route to define routes listening to requests on the/incomes endpoint.Flask provides great documentation on what exactly this does.

To facilitate the process, we currently manipulate incomes asdictionaries. However, we will soon create classes to represent incomes and expenses.

To interact with both endpoints that we have created, we can start our application and issue some HTTP requests:

# start the cashman application./bootstrap.sh &# get incomescurl http://localhost:5000/incomes# add new incomecurl -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/json" -d '{ "description": "lottery", "amount": 1000.0}' http://localhost:5000/incomes# check if lottery was addedcurl localhost:5000/incomes

Mapping Models with Python Classes

Using dictionaries in a simple use case like the one above is enough. However, for more complex applications that deal with different entities and have multiple business rules and validations, we might need to encapsulate our data intoPython classes.

We will refactor our application to learn the process of mapping entities (like incomes) as classes. The first thing that we will do is create a subpackage to hold all our entities. Let's create amodel directory inside thecashman package and add an empty file called__init__.py on it.

# create model directory inside the cashman packagemkdir -p cashman/model# initialize it as a packagetouch cashman/model/__init__.py

Mapping a Python Superclass

We will create three classes in this new directory:Transaction,Income, andExpense. The first class will be the base for the two others, and we will call itTransaction. Let's create a file calledtransaction.py in themodel directory with the following code:

import datetime as dtfrom marshmallow import Schema, fieldsclass Transaction(object): def __init__(self, description, amount, type): self.description = description self.amount = amount self.created_at = dt.datetime.now() self.type = type def __repr__(self): return '<Transaction(name={self.description!r})>'.format(self=self)class TransactionSchema(Schema): description = fields.Str() amount = fields.Number() created_at = fields.Date() type = fields.Str()

Besides theTransaction class, we also defined aTransactionSchema. We will use the latter to deserialize and serialize instances ofTransaction from and to JSON objects. This class inherits from another superclass calledSchema that belongs on a package not yet installed.

# installing marshmallow as a project dependencypipenv install marshmallow

Marshmallow is a popular Python package for converting complex datatypes, such as objects, to and from built-in Python datatypes. We can use this package to validate, serialize, and deserialize data. We won't dive into validation in this article, as it will be the subject of another one. Though, as mentioned, we will usemarshmallow to serialize and deserialize entities through our endpoints.

Mapping Income and Expense as Python Classes

To keep things more organized and meaningful, we won't expose theTransaction class on our endpoints. We will create two specializations to handle the requests:Income andExpense. Let's make a module calledincome.py inside themodel package with the following code:

from marshmallow import post_loadfrom .transaction import Transaction, TransactionSchemafrom .transaction_type import TransactionTypeclass Income(Transaction): def __init__(self, description, amount): super(Income, self).__init__(description, amount, TransactionType.INCOME) def __repr__(self): return '<Income(name={self.description!r})>'.format(self=self)class IncomeSchema(TransactionSchema): @post_load def make_income(self, data, **kwargs): return Income(**data)

The only value that this class adds for our application is that it hardcodes the type of transaction. This type is aPython enumerator, which we still have to create, that will help us filter transactions in the future. Let's create another file, calledtransaction_type.py, insidemodel to represent this enumerator:

from enum import Enumclass TransactionType(Enum): INCOME = "INCOME" EXPENSE = "EXPENSE"

The code of the enumerator is quite simple. It just defines a class calledTransactionType that inherits fromEnum and that defines two types:INCOME andEXPENSE.

Lastly, let's create the class that represents expenses. To do that, let's add a new file calledexpense.py insidemodel with the following code:

from marshmallow import post_loadfrom .transaction import Transaction, TransactionSchemafrom .transaction_type import TransactionTypeclass Expense(Transaction): def __init__(self, description, amount): super(Expense, self).__init__(description, -abs(amount), TransactionType.EXPENSE) def __repr__(self): return '<Expense(name={self.description!r})>'.format(self=self)class ExpenseSchema(TransactionSchema): @post_load def make_expense(self, data, **kwargs): return Expense(**data)

Similar toIncome, this class hardcodes the type of the transaction, but now it passesEXPENSE to the superclass. The difference is that it transforms the givenamount to be negative. Therefore, no matter if the user sends a positive or a negative value, we will always store it as negative to facilitate calculations.

Serializing and Deserializing Objects with Marshmallow

With theTransaction superclass and its specializations adequately implemented, we can now enhance our endpoints to deal with these classes. Let's replace./cashman/index.py contents to:

from flask import Flask, jsonify, requestfrom cashman.model.expense import Expense, ExpenseSchemafrom cashman.model.income import Income, IncomeSchemafrom cashman.model.transaction_type import TransactionTypeapp = Flask(__name__)transactions = [ Income('Salary', 5000), Income('Dividends', 200), Expense('pizza', 50), Expense('Rock Concert', 100)]@app.route('/incomes')def get_incomes(): schema = IncomeSchema(many=True) incomes = schema.dump( filter(lambda t: t.type == TransactionType.INCOME, transactions) ) return jsonify(incomes)@app.route('/incomes', methods=['POST'])def add_income(): income = IncomeSchema().load(request.get_json()) transactions.append(income) return "", 204@app.route('/expenses')def get_expenses(): schema = ExpenseSchema(many=True) expenses = schema.dump( filter(lambda t: t.type == TransactionType.EXPENSE, transactions) ) return jsonify(expenses)@app.route('/expenses', methods=['POST'])def add_expense(): expense = ExpenseSchema().load(request.get_json()) transactions.append(expense) return "", 204if __name__ == "__main__": app.run()

The new version that we just implemented starts by redefining theincomes variable into a list ofExpenses andIncomes, now calledtransactions. Besides that, we have also changed the implementation of both methods that deal with incomes. For the endpoint used to retrieve incomes, we defined an instance ofIncomeSchema to produce a JSON representation of incomes. We also usedfilter to extract incomes only from thetransactions list. In the end we send the array of JSON incomes back to users.

The endpoint responsible for accepting new incomes was also refactored. The change on this endpoint was the addition ofIncomeSchema to load an instance ofIncome based on the JSON data sent by the user. As thetransactions list deals with instances ofTransaction and its subclasses, we just added the newIncome in that list.

The other two endpoints responsible for dealing with expenses,get_expenses andadd_expense, are almost copies of theirincome counterparts. The differences are:

- instead of dealing with instances of

Income, we deal with instances ofExpenseto accept new expenses, - and instead of filtering by

TransactionType.INCOME, we filter byTransactionType.EXPENSEto send expenses back to the user.

This finishes the implementation of our API. If we run our Flask application now, we will be able to interact with the endpoints, as shown here:

# start the application./bootstrap.sh# get expensescurl http://localhost:5000/expenses# add a new expensecurl -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/json" -d '{ "amount": 20, "description": "lottery ticket"}' http://localhost:5000/expenses# get incomescurl http://localhost:5000/incomes# add a new incomecurl -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/json" -d '{ "amount": 300.0, "description": "loan payment"}' http://localhost:5000/incomes

Dockerizing Flask Applications

As we are planning to eventually release our API in the cloud, we are going to create aDockerfile to describe what is needed to run the application on a Docker container. We need toinstall Docker on our development machine to test and run dockerized instances of our project. Defining a Docker recipe (Dockerfile) will help us run the API in different environments. That is, in the future, we will also install Docker and run our program on environments likeproduction andstaging.

Let's create theDockerfile in the root directory of our project with the following code:

# Using lightweight alpine imageFROM python:3.8-alpine# Installing packagesRUN apk updateRUN pip install --no-cache-dir pipenv# Defining working directory and adding source codeWORKDIR /usr/src/appCOPY Pipfile Pipfile.lock bootstrap.sh ./COPY cashman ./cashman# Install API dependenciesRUN pipenv install --system --deploy# Start appEXPOSE 5000ENTRYPOINT ["/usr/src/app/bootstrap.sh"]

The first item in the recipe defines that we will create our Docker container based on the defaultPython 3 Docker image. After that, we update APK and installpipenv. Havingpipenv, we define the working directory we will use in the image and copy the code needed to bootstrap and run the application. In the fourth step, we usepipenv to install all our Python dependencies. Lastly, we define that our image will communicate through port5000 and that this image, when executed, needs to run thebootstrap.sh script to start Flask.

Note: For our

Dockerfile, we use Python version 3.8, however, depending on your system configuration,pipenvmay have set a different version for Python in the filePipfile. Please make sure that the Python version in bothDockerfileandPipfileare aligned, or the docker container won't be able to start the server.

To create and run a Docker container based on theDockerfile that we created, we can execute the following commands:

# build the imagedocker build -t cashman .# run a new docker container named cashmandocker run --name cashman \ -d -p 5000:5000 \ cashman# fetch incomes from the dockerized instancecurl http://localhost:5000/incomes/

TheDockerfile is simple but effective, and using it is similarly easy. With these commands and thisDockerfile, we can run as many instances of our API as we need with no trouble. It's just a matter of defining another port on the host or even another host.

Securing Python APIs with Auth0

Securing Python APIs with Auth0 is very easy and brings a lot of great features to the table. With Auth0, we only have to write a few lines of code to get:

- A solididentity management solution, includingsingle sign-on

- User management

- Support forsocial identity providers (like Facebook, GitHub, Twitter, etc.)

- Enterprise identity providers (Active Directory, LDAP, SAML, etc.)

- Ourown database of users

For example, to secure Python APIs written with Flask, we can simply create arequires_auth decorator:

# Format error response and append status codedef get_token_auth_header(): """Obtains the access token from the Authorization Header """ auth = request.headers.get("Authorization", None) if not auth: raise AuthError({"code": "authorization_header_missing", "description": "Authorization header is expected"}, 401) parts = auth.split() if parts[0].lower() != "bearer": raise AuthError({"code": "invalid_header", "description": "Authorization header must start with" " Bearer"}, 401) elif len(parts) == 1: raise AuthError({"code": "invalid_header", "description": "Token not found"}, 401) elif len(parts) > 2: raise AuthError({"code": "invalid_header", "description": "Authorization header must be" " Bearer token"}, 401) token = parts[1] return tokendef requires_auth(f): """Determines if the access token is valid """ @wraps(f) def decorated(*args, **kwargs): token = get_token_auth_header() jsonurl = urlopen("https://"+AUTH0_DOMAIN+"/.well-known/jwks.json") jwks = json.loads(jsonurl.read()) unverified_header = jwt.get_unverified_header(token) rsa_key = {} for key in jwks["keys"]: if key["kid"] == unverified_header["kid"]: rsa_key = { "kty": key["kty"], "kid": key["kid"], "use": key["use"], "n": key["n"], "e": key["e"] } if rsa_key: try: payload = jwt.decode( token, rsa_key, algorithms=ALGORITHMS, audience=API_AUDIENCE, issuer="https://"+AUTH0_DOMAIN+"/" ) except jwt.ExpiredSignatureError: raise AuthError({"code": "token_expired", "description": "token is expired"}, 401) except jwt.JWTClaimsError: raise AuthError({"code": "invalid_claims", "description": "incorrect claims," "please check the audience and issuer"}, 401) except Exception: raise AuthError({"code": "invalid_header", "description": "Unable to parse authentication" " token."}, 400) _app_ctx_stack.top.current_user = payload return f(*args, **kwargs) raise AuthError({"code": "invalid_header", "description": "Unable to find appropriate key"}, 400) return decorated

Then use it in our endpoints:

# Controllers API# This doesn't need authentication@app.route("/ping")@cross_origin(headers=['Content-Type', 'Authorization'])def ping(): return "All good. You don't need to be authenticated to call this"# This does need authentication@app.route("/secured/ping")@cross_origin(headers=['Content-Type', 'Authorization'])@requires_authdef secured_ping(): return "All good. You only get this message if you're authenticated"

To learn more about securingPython APIs with Auth0, take a look at this tutorial. Alongside with tutorials for backend technologies (like Python, Java, and PHP),theAuth0 Docs webpage also provides tutorials forMobile/Native apps andSingle-Page applications.

Next Steps

In this article, we learned about the basic components needed to develop a well-structured Flask application. We looked at how to usepipenv to manage the dependencies of our API. After that, we installed and used Flask and Marshmallow to create endpoints capable of receiving and sending JSON responses. In the end, we also looked at how to dockerize the API, which will facilitate the release of the application to the cloud.

Although well structured, our API is not that useful yet. Among the things that we can improve, we are going to cover the following topics in the following article:

- Database persistence with SQLAlchemy

- Add authorization to a Flask API application

- How to handle JWTs in Python

Stay tuned!

Follow the conversation