Anequestrian statue is astatue of a rider mounted on ahorse, from theLatineques, meaning 'knight', deriving fromequus, meaning 'horse'.[1] A statue of a riderless horse is strictly anequine statue. A full-sized equestrian statue is a difficult and expensive object for any culture to produce, and figures have typically been portraits of rulers or, in the Renaissance and more recently, military commanders.

Although there are outliers, the form is essentially a tradition inWestern art, used for imperial propaganda by the Roman emperors, with a significant revival inItalian Renaissance sculpture, which continued across Europe in the Baroque, as mastering the large-scale casting of bronze became more widespread, and later periods.

Statues at well under life-size have been popular in various materials, includingporcelain, since the Renaissance. The riders in these may not be portraits, but figures fromclassical mythology or generic figures such asNative Americans.

Equestrian statuary in the West dates back at least as far asArchaic Greece. Found on theAthenian acropolis, the sixth-century BC statue known as theRampin Rider depicts akouros mounted on horseback.

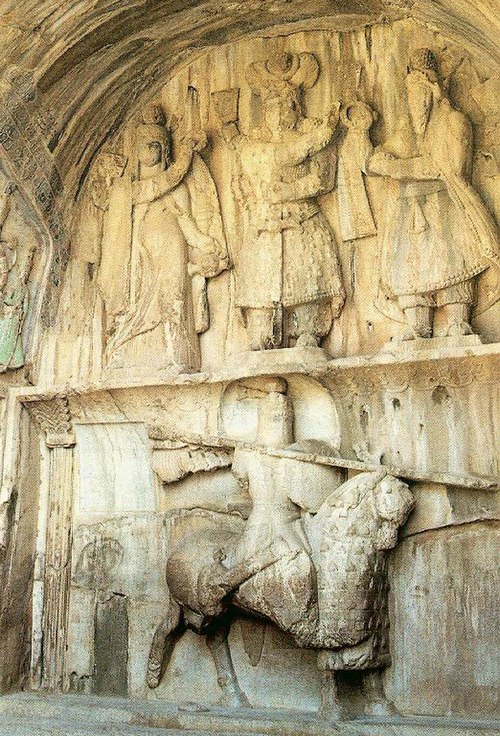

A number of ancientEgyptian,Assyrian andPersianreliefs show mounted figures, usually rulers, though no free-standing statues are known. The ChineseTerracotta Army has no mounted riders, though cavalrymen stand beside their mounts, but smallerTang dynasty pottery tomb Qua figures often include them, at a relatively small scale. No Chinese portrait equestrian statues were made until modern times; statues of rulers are not part of traditional Chinese art, and indeed even painted portraits were only shown to high officials on special occasions until the eleventh century.[2]

Such statues frequently commemorated military leaders, and those statesmen who wished tosymbolically emphasize the active leadership role undertaken since Roman times by the equestrian class, theequites (plural ofeques) or knights.

There were numerousbronze equestrian portraits (particularly of the emperors) inancient Rome, but they did not survive because they were melted down for reuse of the alloy ascoin,church bells, or other, smaller projects (such as new sculptures for Christian churches); the standingColossus of Barletta lost parts of his legs and arms to Dominican bells in 1309. Almost the only sole survivingRoman equestrian bronze, theequestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius in Rome, owes its preservation on theCampidoglio, to the popular misidentification ofMarcus Aurelius, the philosopher-emperor, withConstantine the Great, the Christian emperor. TheRegisole ("Sun King") was a bronze classical or Late Antique equestrian monument of a ruler, highly influential during the Italian Renaissance but destroyed in 1796 in the wake of theFrench Revolution. It was originally erected atRavenna, but moved toPavia in the Middle Ages, where it stood on a column before the cathedral. A fragment of an equestrian portrait sculpture ofAugustus has also survived.

Equestrian statues were not very frequent in theMiddle Ages. Nevertheless, there are some examples, like theBamberg Horseman (German:Der Bamberger Reiter), inBamberg Cathedral. Another example is theMagdeburg Reiter, in the city ofMagdeburg, that depicts EmperorOtto I. This is in stone, which is fairly unusual at any period, though the Gothic statues at less than life-size at theScaliger Tombs inVerona are also in stone.

There are a few roughly half-size statues ofSaint George and the Dragon, including the famous ones inPrague andStockholm. A well-known small bronzeequestrian statuette of Charlemagne (or another emperor) in Paris may be a contemporary portrait ofCharlemagne, although its date and subject are uncertain.

After the Romans, no surviving monumental equestrian bronze was cast in Europe until 1415–1450, whenDonatello created the heroic bronzeequestrian statue of Gattamelata thecondottiere, erected inPadua. In fifteenth-century Italy, this became a form to memorialize successful mercenary generals, as evidenced by the painted equestrian funerary monuments toSir John Hawkwood andNiccolò da Tolentino inFlorence Cathedral, and thestatue of Bartolomeo Colleoni (1478–1488) cast byVerrocchio inVenice.

Leonardo da Vinci had planned acolossal equestrian monument to the Milanese ruler, Francesco Sforza, but was only able to create a clay model. The bronze was reallocated for military use in theFirst Italian War.[3] Similar sculptures have survived in small scale:The Wax Horse and Rider (c. 1506–1508) is a fragmentary model for an equestrian statue ofCharles d'Amboise.[4] TheRearing Horse and Mounted Warrior in bronze was also attributed to Leonardo.

Titian's equestrian portrait ofCharles V, Holy Roman Emperor, of 1548 applied the form again to a ruler. Theequestrian statue of Cosimo I de' Medici (1598) byGiambologna in the center ofFlorence was a life size representation of the Grand-Duke, erected by his son Ferdinand I.

Ferdinand himself would be memorialized in 1608 with an equestrianstatue in Piazza della Annunziata was completed by Giambologna's assistant,Pietro Tacca. Tacca's studio would produce such models for the rulers in France and Spain. His last public commission was the colossal equestrian bronze ofPhilip IV, begun in 1634 and shipped to Madrid in 1640. In Tacca's sculpture, atop a fountain composition that forms the centerpiece of the façade of the Royal Palace, the horse rears, and the entire weight of the sculpture balances on the two rear legs, and discreetly, its tail, a novel feat for a statue of this size.

During the age ofAbsolutism, especially inFrance, equestrian statues were popular with rulers;Louis XIV was typical in having one outside hisPalace of Versailles, and the over life-size statue in thePlace des Victoires in Paris byFrançois Girardon (1699) is supposed to be the first large modern equestrian statue to be cast in a single piece; it was destroyed in theFrench Revolution, though there is a small version in theLouvre. The near life-size equestrian statue ofCharles I of England byHubert Le Sueur of 1633 atCharing Cross in London is the earliest large English example, which was followed by many.

The equestrian statue of KingJosé I of Portugal, in thePraça do Comércio, was designed byJoaquim Machado de Castro after the1755 Lisbon earthquake and is a pinnacle of Absolutist age statues in Europe. TheBronze Horseman (Russian:Медный всадник, literally "The Copper Horseman") is an iconic equestrian statue, on a huge base, ofPeter the Great of 1782 byÉtienne Maurice Falconet inSaint Petersburg,Russia. The use of French artists for both examples demonstrates the slow spread of the skills necessary for creating large works, but by the nineteenth century most large Western countries could produce them without the need to import skills, and most statues of earlier figures are actually from the nineteenth or early twentieth century.

In the colonial era, an equestrian statue ofGeorge III by English sculptorJoseph Wilton stood onBowling Green inNew York City. This was the first such statue in the United States, erected in 1770 but destroyed on July 9, 1776, six days after theDeclaration of Independence.[5] The 4,000-pound (1,800 kg) gilded lead statue was toppled and cut into pieces, which were made into bullets for use in theAmerican Revolutionary War.[6] Some fragments survived and in 2016 the statue was recreated for a museum.[7]

In the United States, the first three full-scale equestrian sculptures erected wereClark Mills'Andrew Jackson (1852) inWashington, D.C.;Henry Kirke Brown'sGeorge Washington (1856) inNew York City; andThomas Crawford's George Washington inRichmond, Virginia (1858). Mills was the first American sculptor to overcome the challenge of casting a rider on a rearing horse. The resulting sculpture (of Jackson) was so popular he repeated it forNew Orleans,Nashville, andJacksonville.

Cyrus Edwin Dallin made a specialty of equestrian sculptures of American Indians: hisAppeal to the Great Spirit stands before theMuseum of Fine Arts,Boston. TheRobert Gould Shaw Memorial in Boston is a well-knownrelief including an equestrian portrait.

As the twentieth century progressed, the popularity of the equestrian monument declined sharply, as monarchies fell and the military use of horses virtually vanished. Thestatue of Queen Elizabeth II riding Burmese inCanada, and statues ofRani Lakshmibai inGwalior andJhansi, India, are some of the rare portrait statues with female riders. (AlthoughJoan of Arc has been so portrayed a number of times,[8] and anequestrian statue of Queen Victoria features prominently inGeorge Square, Glasgow). In America, the late 1970s and early 1980s witnessed something of a revival in equestrian monuments, largely in theSouthwestern United States. There, art centers such asLoveland, Colorado, Shidoni Foundry inNew Mexico, and various studios inTexas once again began producing equestrian sculpture.

These revival works fall into two general categories, the memorialization of a particular individual or the portrayal of general figures, notably the Americancowboy orNative Americans. Such monuments can be found throughout the American Southwest.

In Glasgow, the sculpture of Lobey Dosser on El Fidelio, erected in tribute toBud Neill, is claimed to be the only two-legged equestrian statue in the world.

The monument to generalJose Gervasio Artigas inMinas, Uruguay (18 meters tall, 9 meters long, 150,000 kg), was the world's largest equestrian statue until 2008. The current largest is the 40-meter-tallequestrian statue of Genghis Khan at Boldog, 54 km fromUlaanbaatar,Mongolia, where, according to legend,Genghis Khan found thegolden whip.

TheMarjing Polo Statue, standing in theMarjing Polo Complex,Imphal East,Manipur (122 feet (37 m) tall[a][9][10]), completed in 2022–23, is the world's tallest equestrian statue of apolo player. It depicts ancient Meitei deityMarjing, aMeitei horse (Manipuri pony) andSagol Kangjei (Meitei for 'polo').[11][12]

The world's largest equestrian sculpture, when completed, will be theCrazy Horse Memorial inSouth Dakota, at a planned 641 feet (195 m) wide and 563 feet (172 m) high, even though only the upper torso and head of the rider and front half of the horse will be depicted. Also on a huge scale, the carvings onStone Mountain inGeorgia, the United States, are equestrian sculpture rather than true statues, the largestbas-relief in the world. The world's largest equestrianbronze statues are theJuan de Oñate statue (2006) inEl Paso, Texas; a 1911 statue inAltare della Patria inRome; and thestatue of Jan Žižka (1950) inPrague.[13]

In many parts of the world, anurban legend states that if the horse is rearing (both front legs in the air), the rider died in battle; one front leg up means the rider was wounded in battle; and if all four hooves are on the ground, the rider died outside battle. A rider depicted as dismounted and standing next to their horse often indicates that both were killed during battle.[14] For example,Richard the Lionheart is memorialised, mountedpassant, outside thePalace of Westminster byCarlo Marochetti; the former died 11 days after his wound, sustained in siege, turned septic. A survey of 15 equestrian statues in central London by theLondonist website found that nine of them corresponded to the supposed rule, and considered it "not a reliable system for reading the fate of any particular rider".[15]

In the United States, the rule is especially held to apply to equestrian statues commemorating theAmerican Civil War and theBattle of Gettysburg.[16][17] One such statue was erected in 1998 inGettysburg National Military Park, and is ofJames Longstreet, who is featured on his horse with one foot raised, even though Longstreet was not wounded in that battle. However, he was seriously wounded in theBattle of the Wilderness the following year. This is not a traditional statue, as it does not place him on apedestal. One writer claims that any correlation between the positioning of hooves in a statue and the manner in which a Gettysburg soldier died is a coincidence.[18] There is no proper evidence that these hoof positions correlate consistently with the rider's history but some hold to the belief regardless.[19][20]

Shri Amit Shah inaugurated Medical College of worth Rs. 46 Crore at Churachandpur and unveils 122 feet tall Marjing polo statue of worth Rs. 39 crore