What the housewife used to cook meals: fireplace hangers, pot cranes, fire and cup dogs, tongs and other implements

Gertrude Jekyll [adapted byGeorge P. Landow]

[Victorian Web Home —>Political History —>Social History —>Technology —>Technology in the Home]

[The following comes from "The Hearth and Its Implements," the third chapter of Gertrude Jekyll'sOld English Household Life (1925), some of the material of which previously appeared in her 1904 volume,Old West Surrey. The photographs and drawings are probably all hers.GPL scanned and formatted text and images, added headings, and cut and rearranged some portions of the text, moving, for example, the section on cooking pots earlier in the text here than in the original.].

Fireplace Hangers

Wooden "Crochan" from the Hebrides. [Click on thumbnail for larger image.]

WHEN wood was the only fuel, except peat, in country districts,the wide "down" hearth was commonly used both for cookingand warming. It was equally suitable where, in some remote moorlandplaces, there was no true peat for the alternative fuel — parings of peaty soils containing tufts of heath and gorse. In the simplest cottages the usual cooking utensil was the three-legged iron pot. It could either stand in the hot ashes on its three short legs or hang by the swinging handle, the chimney was the wooden chimney bar, stretching across, the ends let into the masonry. It was of oak, or preferably, of chestnut; in section higher than wide and with the upper edge rounded. Over this passed the curved top end of the hanger, an iron bar with a flat sheet-iron ratchet attachment looking like a coarse saw. The lowest end of the upright had either a closed loop or a knob, from which hung the hook that caught one of the teeth of the ratchet. The hanger could thus be set either high or low, according to the liveliness of the fire or the degree of heat required for the cooking. The most primitive form of hangerwas the wooden "crochan," by which the pot, slung from above by ahazel rope, hung over the fire (at right).

Some of the older hangers have an ornament at the top, usually a fleur-de-lys, or it might be a kind of lance head, or only a close curl of the end of the iron that connected the upper part of the ratchet with the upright bar (see "A" below). A rare example of a highly ornamented hanger is in the Victoria and Albert Museum. The loop that catches in the ratchet is decorated with elaborate scroll work and the lower part is pierced through, showing a silhouette of the smith at work, withsome of his tools above ("C" below).

Chimney and Pot Cranes

Two Cranes, one from Pembrokeshire, the other from Glamorganshire.

In farms and the better class of houses something more than thesimple hanger was wanted. The fire was large and wide spread so thatone point or another of its area might be the more convenient place forthe cooking pot. Some contrivance for meeting this alternative wasby the chimney crane or pot crane; this was of two forms, one in whichthe horizontal bar was simply supported by a diagonal stay andthe height of the pot adjusted by a short hanger at any point along thebar, and the other in which there are two movements of the craneitself; one to swing forward and back, and the other for raising orlowering the hook that holds the pot or kettle. In both forms themain vertical iron, the backbone of the whole concern, is so held attop and bottom that it can swing forward like a gate. The bottomend is commonly fitted into a pieceof hard stone and the top into aloop in an iron cramp built into thewall. At a certain distance alongthe horizontal arm a short ironstrap suspends a lever or handlethat has a hanging hook at the fireend, while the handle end restsunder any one of the projectingbuttons on the quadrant that isfixed near the upright, and thus thepot is held at any height above thefire. These cranes, made duringthe seventeenth and eighteenthcenturies, show a great diversity ofornament. The main part of the structure was determined bythe necessities of its use, and the smith then exercised his own powersof invention, taste and skill in various methods of enrichment.Sometimes it is only in the line or play of the different straps and stays;which, after doing their constructional work, were drawn out intocurls or volutes with more or less closed ends, or it may be some ornamentaltwists of the square sectioned iron bar, or a little spray of leaf and flower,or even a whole tree with leafy branches and scroll tendrils.

Firedogs, Spits, and Cup-dogs

Left: Cottage Fire-dogs. Right: Cup-dog for warming drinks.

A simple form of iron firedog was in use in every cottage, generallyof low shape so as not to interfere with the swinging pot; the uprightfront being only high enough to stop a log of reasonable thickness fromrolling out forwards; and there were two loose iron bars that could beadjusted on the dogs so as to hold a cooking pot. But in some farmhouses,and even cottages, there were the tall-fronted cup dogs, with the topsframed in such a way as to hold a mug of hot drink.

In these and inmany other forms of tall-fronted dogs there was often an arrangement forsupporting a spit. The illustration of the basket or cardle sspit immediately above shows one with movableloops; these would bring the spit to the front of the dogs. The loops orhooks were more frequently and more conveniently fixed to the back of thedogs, nearer to the fire. It was the pride of the good housewife to keepher spits bright, and they showed finely when displayed in the spitrackover the front of the fireplace. These spitracks were sometimes quiteplain, but usually with the fronts of tlie projections handsomely moulded.Sometimes the spit was worked by a smoke-jack, a piece of mechanismwhose power was derived from the draught in the chimney. In thiscase the spit had a circular disk at one end, the edge grooved to takethe chain that connected it with the jack.

In some old spits this circularwheel was larger, pointing to its having been used in the older days whenturnspit dogs were the motive power. From the spit, a chain or cordwas conveyed to the dog wheel fixed at some convenient height againstthe wall of the kitchen. The dog worked inside the wheel, whose flooringhad transverse battens for his foothold. They were small, short legged,long bodied dogs, something the shape of a dachshund.

Thomas Rowlandson,A Dog Turnspit in a Kitchen at Newcastle Emlyn, South Wales.

Nowadays we roast more conveniently by hanging the jointvertically to the clockwork jack ; this also is better suited to the narrowshape of our coal fires. But in the old days, when the fire was on thehearth and was large and wide shaped to take a large piece of meat, therewas no other way of roasting than the horizontal. For a heavy pieceof meat there were two usual forms of spit; one with two prongs whichheld it firm and the other, called a basket or cradle spit, in which themeat was enclosed, and held by a number of thin iron bars (see below).This was specially convenient for cooking a tender viand like a suckingpig, in whose case it was desirable to avoid piercing the meat and soletting out the succulent juices.

Left: Basket or Cradle Spit. Right: Pronged Roasting Spit. Note the pulleys at the left of each, which orginally connected to a smoke jack, a mechansm that rotated the cooking meat — an early version of a rotisserie.

Many a pair of handsome old firedogs that had been in manorialhouses found their way into farmhouses and cottages when iron firegratescame into use in the kitchens of houses of the better class. Some ofthem, of pure Gothic design, are of great antiquity. They might oftenbe found fifty years ago in Surrey and Sussex, when attendance at farmsales in remote country places gave an opportunity of collecting manyinteresting relics of the older days.

Cooking Pots

The main cooking utensil was the iron pot, still made and now largelyexported to some half-barbarous peoples. It would either swing fromthe hook of a hanger or stand down in the ashes. There were also skilletsof brass or bronze which appear to have been cast in one piece. Theywere thick and heavy and look as if they would wear and endure forever. In fact, a great many more of these would have been still in existence but that in Jacobean times a quantity were called in and melteddown for bronze coinage. A later form of skillet was of wroughtbrass, much thinner. This kind had a projecting rim, the brass beingbrought over a wired edge, and they dropped into iron holders on threelegs. Large brass cauldrons were used for heating milk in cheesemaking. Iron trivets, on which any cooking pot could be stood, oranything placed to keep warm, were in many good patterns.Fryingpans had the handles very long, sometimes as much as three and halffeet; the necessity of this will be seen when the size of the wood fire andthe distance for the comfort of the operator are considered.

Various skillets. This kind of cookware has legs to raise it above the floor of the fireplace and coals.

There were also earthen cooking pots ; pipkins with handles, instoneware with a dull glaze, both inside and out, and in different kindsof earthenware; some all glazed, and others, of the commonest kind,of the ordinary redware, glazed inside only. They were used eitherseated in the hot ashes or raised on trivets. Cakes and small loaveswere baked in the ashes under a redware pot turned upside down. The girdle, still much used in the north and occasionally all over England,is of great antiquity; it can either hang to a hanger or stand on a trivet.

Pipkins in stoneware and glazed earthenware.

Tongs, Fire Shovels, and Other Cooking Implements

The tongs and fire shovels of the older times were of a fine simpleshape, in happy contrast to the implements of the same name now tobe found in shops, for the most part of bad design or overloaded withuseless, so-called ornament. The reason is not far to seek, for the oldtongs were made for actual use by the nearest smith, while the modernthing is one of thousands of the same, out of the ironmonger's patternbook. Really beautiful were some of the old brand tongs, small thingsto be held in one hand for picking up a brand and blowing it into flamefor lighting a pipe or arushlight.

Toaster and potato rack.

Several forms of toasting implements were in use with the downfire; some quite low for the cottage for toasting bacon or bread.They stood on three short legs — two of them forward, under the actualtoaster, and one half-way back, under the handle. The head with itstwo hoops was on a loose rivet and could be twisted a little way to oneside or the other. The implement that is shown with the toaster isfor raking hot potatoes out of the ashes. There were larger and moreelaborate toasters in better houses, with tripod legs supporting anupright to which the actual toasting I'ork was fixed. In both theexamples shown in Fig. 56 the toasting part slides up and down thestandard and also revolves upon it, while it is kept in uny position thatmay be desired by the pressure of a spring. In the one on the right handthere is another movement, for the horizontal fork pulls backward andforward.

Left: Three Idlebacks.

Right: A Tea kettle hanging on an Idleback attached to an adjustable metal hanger.

A favourite device for tipping a kettle without taking it off the firewas the idleback or lazyback (Figs. 61-2). It hung on the hanger andit will be seen from tlie illustration how the act of pulling downthe handle will tip the kettle. The hook nearest the spout has a springclip that keeps the front of the kettle handle down when it is tipped forpouring. The old smith who forged it could not resist the suggestion ofsnake-like form in the handle of the tipper, for he finished off the end ina little snake's head. If it is noticed that in the picture the kettle doesnot hang level, it is because it is the way it takes of itself after being tipped.

A piece of old waggon tire, stood on edge, was commonly used incottages as a fender, and a very handy fender it makes; standing fourinches high and about twenty inches long and with a pleasant curve, itwas a neat way of keeping the ashes of the front of the fire in place.

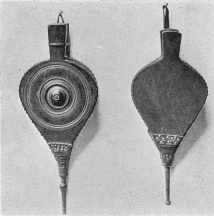

Bellows

Bellows have been in use for all time, but from their construction ofwood and leather and from the need of their constant employment they hadnecessarily a rather short lifetime, and examples of those in common usedating further back than a hundred and fifty years are rare, thoughthere are much older specimens in museums of a highly ornamentalkind, in which both wooden faces were richly carved. The oldest weknow of for ordinary household use had much longer handles and shorterbodies than the later patterns. A good kind of the late eighteenth andearly nineteenth centuries had the turned body of a. dark hardwood, asshown in one of the examples illustrated. This had a nicelyformed brass nozzle, and was altogether a shapely article. The ordinarykitchen bellows with elm body that is still to be had follows this, though oncoarser lines.

Left: Traditional Bellows. Right: A Nineteenth-century mechanical bellows. [Click on thumbnail for larger image.]

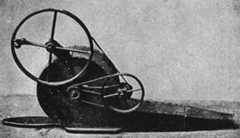

An ingenious form of bellows, giving a continuous blast,was in use in the early years of the nineteenth century. It has adrum-shaped body narrowing into a square channel that ends in a brassnozzle. Inside the drum is a wheel with floats. Outside there is anarrangement of two wheels with driving bands, the larger with a handle,which turn the wheel within, the multiplied power making a steadydraught. There is an old saying among cottage folk in Sussex descriptiveof some situation that is full of difficulty or almost hopeless: "It is acase of green wood and no bellows."

Bibliography

Jekyll, GertrudeOld English Household Life: Some Account of Cottage Objects and Country Folk. London: B. T. Batsford, 1925.

Jekyll, GertrudeOld West Surrey: Some Notes and Memories. London: Longmans, Green, & Co, 1904.

Victorian

Web

Technology

Social

History

At Home

3 February 2009