The kingdoms of the Bahamanis(1348-1527 C.E.) and theAdilshahis (1489-1686 C.E.) in the north of Karnatakaand the interregnum ofHyder Ali andTippu Sultan(1761-1799 C.E.) in Mysore were the main Islamic kingdoms inKarnataka. In the southern part ofthe state they may be remembered for the boost they provided to Islamiclearning, arts, crafts, and rise of the Urdu language and literature. None ofthese rulers displayed an inclination towards traditional methods of recordingevents, such as palm books and stone inscriptions, but they had court historianswho recorded important events of the reigns of their respective patrons. Inspite of a certain degree of bias and exaggeration, books by these historiansprovide some valuable information. Travelers' accounts, Kaifiats andBakhairs provide additional glimpses into the educational system prevalent amongMuslims.

It is known that Prophet Mohammadlacked formal education. He was a visionary and had no need for literatetraining, but had all the respect for learning and scholarship. He declared thatextensive knowledge (through reading) is the only medium for earthly andheavenly happiness. "Respecting scholars amounted to respecting oneself,"was his belief. He went a step further to pronounce that "a scholar's ink(pen) is superior to a martyr's blood" which emphasized his regard forscholars. The faithful received the message. With the political conquest camethe spread of Islam and Islamic learning. When they arrived in India, Muslimconquerors energetically attended to the propagation of Prophet Muhammad'steaching. In Iran and other Arabcountries, the mosque was a center of culture and learning and the same systemwas adopted in India1.Masjids (mosques) big and small appeared inthe newly conquered territories.Makhtābsor elementary schools were attached to them, where, in addition to prayer,recitation from the Holy Koran, the Arabic language and arithmetic were taught.

Recitations from the Koran becameobligatory on festive occasions, celebrations and at community gatherings.Knowledge of Arabic was compulsory for administrators, which stood second inimportance only to the reading and understanding of the Koran. Religiousliterature flowered in this period. Political conquests and the spread ofreligion went hand-in-hand.

Slowly, the learning of Persian,which became the court language under theMughals, was introduced inmakhtābs . Themasjidswere endowed with land and cash by the ruling class, which fact alloweddeserving students to take up higher studies inmadrassās(centers of higher learning).

The same pattern, which existed innorth India, was followed in the South. Under theBahamani rule, Islamiceducation received new fillip. Every village in the Deccan with a Muslimpopulation had amasjid andinvariably amakhtāb.Mohallās (neighborhoods) in towns and cities had biggermasjids, whereinmadrassās additionally came into existence. It becameessential to train youngsters as scribes, accountants and readers for theever-growing administrations. Along with the Koran, hādits (traditionalIslamic axioms) and their interpretation were taught, as were mathematics(including geometry), logic, history and the Unani system of medicine. Onlythose students who had completed religious courses and other studies inmakhtābsreceived admission intomadrassās.

Calligraphy was given prominence by the Muslimrulers of Karnataka, over the centuries. The paper had come into existence, andpenmanship, whether original or a copy, got priority. Theology, rhetoric, andastronomy were preferred subjects. Archery, fencing, horse-riding andchaugan(polo) were practiced among the aristocracy. Military training was compulsoryfor princes.

Learnedmullāhsandmoulvis ranmadrassās and well-known makhtābs. Parents escorted students to school (see pictureno. 91) where pious and selfless teachers took their jobs seriously, and assumedproper care of their charges (seepicture no. 93).

© K. L. Kamat

Iinitiation started very early forthe child, in fact at the exact age of four years, four months and four days. Thebismillāhritual was undertaken, wherein the child was dressed in new clothes, and a feastensued, to which family members and relatives were invited. The villagemullāh initiated the boy by making him recite therelevant prayer ofbismillāh,and themullāh received presents for his services. From the next day onwards, the childattended the nearbymakhtāb, where in addition to Persian letters,he learnt songs and moral stories. The book of Bustan was the most popular text,along with the Gulistan. Arabic, Persian grammar and other languages were alsotaught. Correspondence, writing applications and administrative terminology weretaught in these Islamic schools.

© K. L. Kamat

Life in residential Islamicschools started early in the morning with ablutions and prayer, followed by thelessons. Hand-written books were few and usually shared by the youngsters (seepicture no. 94). Practical jokes and mischief were common among students andpunishment was quite severe for errant boys (see picture no.97). Self-study wasimportant, while memorizing and recitationformed part of a lesson (see picture no. 96).

© K. L. Kamat

Education among Muslims in coastalKarnataka seems to have developed without gender bias even in 14thcentury.Ibn Batuta, the Arab traveler, who visited the town ofHonavar in 1336 C.E. as a guest ofthe local ruler Jamaluddin, saw and recorded a rare sight: there weretwenty-three schools for boys and thirteen schools for girls, the likes of whichhe had not seen anywhere. All the women in these schools knew the Koran byheart. In all likelihood they studied inmakhtābs, where learning ofthe Koran received a priority. Ibn Batuta's observation is important for morethan one reason: he had traveled in almost all Muslim countries of the period,in addition to various parts of Southeast Asia, and found the rare presence ofschools for girls and women fit to be recorded in his accounts. He furthermentions that the girls were very beautiful and wore nose rings. This obviouslymeant that they did not put on the veil orburquāah.In contemporary north India, due to the Muslim invasion, even Hindu society wasforced to keep women in strict control, covered with thepurdāh inpublic places. In the south however, and especially in Karnataka, perhaps due topast tradition, Muslim girls, possibly Navayats and new converts to Islam, didnot use the veil and attendedmakhtābs just like boys. Although asolitary situation, the availability of schools for girls was an extraordinarycase in the middles ages, not only for India, but for the entire contemporaryMuslim world.

K.L. Kamat/Kamat's Potpourri

A Student holding a Book

![]()

Hassan Gangu Bahamani (1347-1358C.E.), founder of theBahamani kingdom, came from a humble background and had noeducation. But he paid full attention to educating his sons. His son Muhammadknew several languages, including Turkish, Arabic and Persian, and wrote poetry.But it was Muhammad II (C.E. 1378-1397), the third king, who became famous as apatron of learning. He established schools (makhtābs and madrassās) in Gulburga, Bidar, Kandahar, Elichpur, Doulatabadand Dabhol. He arranged for free boarding and lodging for poor students. Amilitary school was also established for the children of nobles.

Firozshah Bahmani (1398-1422 C.E.)was an accomplished scholar and fond of learning. He sent ships from the port ofGoa to Persia, Turkistan (Turkey), and Egypt carrying special invitations toscholars of Islamic institutions. They were given important posts and facilitiesin order to pursue their studies further. Firozshah was drawn to philosophy andnatural sciences. Every fourth day of the week he copied sixteen pages of theKoran, before engaging in public affairs. He knew Arabic, Turkish, French,Bengali, Gujarati, Telugu and Marathi languages2. It is told that hehad women in hiszenāā (the women's quarters within the royal palace) fromall these regions and used to converse with each in her native tongue!

Discussions on botany, geometryand logic were arranged, in which Firozshah actively participated. He spent hisleisure hours in the company of dervishes, poets and reciters of classics. Heplanned to build an observatory at Daulatabad, under the guidance of the famousastrophysicist Guilani, but the sudden death of the latter put an end to theremarkable aspiration. Firozshah's attempt indicates that many experts inastronomy, mathematics and engineering were in his court and inspired him3.He built a big library at Ahmadnagar (in present dayMaharashtra state), which was in good condition even in the 17th century, when Qasim Ferishta,the court historian of the Adilshahis visited it.

The arrival of Khwaja SadruddinMuhammad Hussain Gesu Daraj, popularly known as Hazrat Banda Nawaz (1321-1422C.E.), a famous Sufi saint to Gulbuga gave a good boost to the Dakhani (or"Deccani")language and literature. Later known as Dakhani Urdu, this was taking shape asan independent and important spoken language. It was a mixture of north IndianHindavi or Hindi, Persian, Gujarati and Marathi, languages spoken by soldierswho came from different regions, and by wandering mendicants and Sufifakirs. Although Banda Nawaz knew Persian well and wrote in thatlanguage, he adopted Dakhani as his medium of instruction and preaching. Hislater works are in this language, which by then had adopted the Persian script.His works are considered the earliest in the Dakhani language of the Muslims forthe entire Deccan Plateau. Persian continued to be the court language of theBahmanis, but through Dakhani, Banda Nawaj reached the masses that were at oncedrawn to Sufi teachings. Banda Nawaz was the foremost disciple of the famousChiraghi, who, along with Nizamuddin Aulia, was the most respected Sufi scholarof his times. At his insistence, Banda Nawaz came south in 1369 C.E. Sufiteachings were directed at the abolition of social inequalities anddiscrimination. All men were equal; the Sufi saints treated the rich and thepoor, Hindus and Muslims, freemen and slaves all alike. Obtaining freedom forslaves was considered a noble act and the upliftment of the poor and thedowntrodden received priority in their interpretation of Islam. Hazrat BandaNawaz became endeared to the masses quite quickly. Due to these teachings, whichspanned over three-quarters of a century, Islam took root in the Deccan andespecially in the Gulbarga, and Bidar regions4. Banda Nawaz also hada good number of non-Muslim followers. Hisdargāh andurs atGulburga are a place of pilgrimage for people of all sects even today.

Mahmud Gawan arrived in Bidar in 1453 C.E. and gave a good boost to thepromotion of education and learning. Although a merchant by vocation, he waswell versed in Islamic lore, Persian language and mathematics. He was also knownfor his profound scholarship in the Middle East before coming to India. Due tohis perseverance, honesty, simplicity and learning, he earned the goodwill ofthe Bahamani rulers and held important posts under three successive kings.Mahmud III (1462-82 C.E.) as a young boy studied under his tutorship, and Gawanbecame the grandvazir or Prime Minister when Mahmud became the king, andlooked after the administration for nearly thirty years

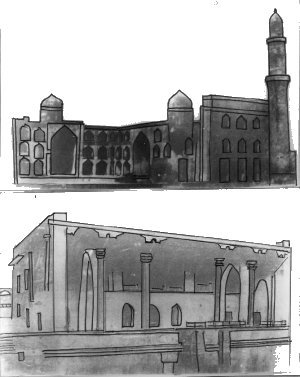

Gawan was rich due to hisadventures in international trade, but spent his entire earnings on thepromotion of education. In 1472 C.E. he established amadrassā inBidar, then the capital of the Bahmanis. Themadrassā consisted ofan imposing three-story building with 100 feet tall minarets in four corners.There were thirty-six rooms for students and six suites for the teaching staff5.The building also had large lecture halls, a prayer hall and a matchless libraryof three thousand volumes. Gawan himself had a personal library of more than athousand books. He spent all his leisure time in the library.

Themadrassā buildinghad a large courtyard with nearly a thousand cubicles, where students andlearned men came from all parts of the country and the East to stay. Boardingand lodging were free. There were 118 students on a permanent basis andcountless itinerant scholars.

Mahmud Gawan was familiar withrenowned colleges at Samarkhand and Khorasan and his own college ormadrassāwas modeled after west Asian architecture6.

Gawan attempted to get renownedscholars from Persia and other West-Asian countries to teach at and head the nowfamous college. But most of them declined the offer due to age or the arduousand long journey involved. Sheikh Ibrahim Multani became head of themadrassā,and finally chiefkāzi of the kingdom; he is credited with thespread of Islamic learning in the state.

Gawan's growing clout in thecourt was a sour issue with Dakhani (local) Muslim leaders. They considered hima foreigner and his influence over the royalty raised a lot of contention. There were administrative reforms introducedby Gawan, which also generated muchresentment among Dakhani governors. The courtiers decided to kill him andhatched a careful plot. They obtained Gawan's seal and affixed it on a blankpiece of paper and forged a letter inviting the king of Orissa to attack theBahamani Kingdom. The letter was duly delivered to the king, who was ofteninebriated. Without verifying the facts, the king sent for Gawan, and askedabout the punishment to be meted out for treason. "Death," was the promptreply from Gawan. The Sultan (king) showed him the letter. Although Gawanadmitted that the seal was his, he pleaded complete innocence about thecontents. Unfortunately the Sultan was not in his senses and ordered Gawan'sbeheading on the spot. Gawan warned the king to use discretion in such seriousallegations. Those were his last words. Thus came the end of the legendaryscholar statesman.

When Gawan's house was raidedfor the alleged wealth he had accumulated, all that could be found was a mat,cooking vessels, the Holy Koran and 144 letters he wrote. Although themadrassāsuffered a heavy loss due to his sudden death, the building continued to stay ingood condition for nearly two centuries. After the capture of Bidar byAurangjebin the late 17th century, the buildings were used for storing apowder magazine and as barracks for a body of cavalry. Unfortunately lightningstruck the powder magazine and there was a huge explosion, destroying thegreater part of the edifice and causing immense damage. Most of the rooms andthe three minarets were destroyed7. Only one minaret and a fewcubicles have survived till date (seepicture no. 98).

K.L. Kamat/Kamat's Potpourri

The Asri Mahal Library

![]()

The Adilshahi Sultans of Bijapur(1489-1686 C.E.) continued the Bahamani tradition of patronage to education byconstructingmasjids andmakhtābs. Among this dynasty ofrulers, Yusuf Adilshah the founder (1499-1510 C.E.) was educated at Sava (inPersia) and had a taste for poetry and music. He could play two to threeinstruments and composed spontaneous songs. Many master musicians and learnedmen were invited by him from Persia, Turkistan and Rome. Ismail Adil Shah(1510-1534 C.E.) was also a patron of scholars and poets. He knew severallanguages, and was adept in drawing, painting and making arrows. Ali Adil Shah I(1535-1558 C.E.) had a philosophical bent of mind and invited Hindu, Muslim andChristian saints for religious discussions and called himself "AdilshahSufi." He had a great liking for books and collected a huge number on avariety of subjects, and carried boxes of books with him during many journeys.The royal library lodged in Asari Mahal at Bijapur had its beginning during hisrule.

Music, the Dakhani language,painting and crafts received a lot of encouragement during theAdilshahi reignin Karnataka. Calligraphy grew in all its grace and elegance. The Persian scriptrenders itself beautifully to an artist's imagination and skill. An artist ora sensitive calligraphist can give flowing touches, flowery flourishes or longand short joints to letters. Islamic calligraphy developed into seven styles ata later date. Thekufi style wasemployed for religious sayings or quotations from the Koran, thenasqfor simple forms in everyday correspondence and thetulupwas used for epitaphs of heroes and martyrs.Nastaliqandjughra were the other two styles,even more in vogue. Thetughra wasused to avoid the evil eye (an Indian belief analogous to the western scarecrow)and were to be found in forts and fortresses of the Deccanregion.

As the use of paper becameincreasingly popular, calligraphists grew in demand. Khasnavis was an expert incalligraphy. Hindus and Muslims were equally adept in handwriting. Books onpoetry, biography and history were illustrated with the choicest handwriting,with beautiful borders of gold, red and blue flowers.

Ibrahim Adilshah II (1580-1627 C.E.)is remembered as the greatest king, for trying to bring in cultural harmonythrough music and other fine arts. His book, "Kitab-E-Navras" (book of nineflavours) in the Dakhani language is a collection of 59 poems and seventeencouplets. According to his court poet Zuhuri, Ibrahim Adilshah wrote the book tointroduce the theory of nine juices(which occupies the most important place in Indian aesthetics) to people who had only a Persian background. The book startswith a prayer to Sarasvati, the goddess of learning. He composed verses onGanapati, the god of learning, as well. He proudly claimed that his father wasthe divine Ganapati, and his mother the holy Sarasvati. For him, thetānpurā(a musical instrument) personified learning, and it was said that "Ibrahim theTanpurawala became learned due to the grace of God, by living in the city oflearning i.e., Vidyanagari." Vidyanagari was the earlier name of Bijapur.

Ibrahim II publicly declared thatall he wanted wasvidyā, or learning, music, andgurusevā(service of theguru.) He was a devotee of Hazrat Banda Nawaz, the Sufi saint. He composed a prayer to his teacher, requesting him to bestow vidyāand a charitable disposition.

To provide a constructive shape to hisinterpretation of the rasas, he founded the new township of Navraspur. He had atemple built forGoddess Saraswati within the precincts of the palace, which stillstands and is known as "Narasimha Sarasvati Mandir." The record ofencouragement he provided to music and musicians is amazing, considering thatmainstream Islam does not recognize music as a path of devotion. Ibrahim himselfhad mastered music and wanted his subjects to cultivate a love for it. Hiscreation of the Eid-e-Navras and the Lashkar-e-Navras is unique. They aredescribed below.

On every Thursday, Eid-e-Navras(festival of music) was held in Bijapur. Singers, players of various musicalinstruments, and dancers from different parts of the kingdom assembled for thefestival. The assembly of elite musicians was known asLashkar-e-Navras.Men and women of noble birth aspired to participate in this Eid. Well-knownmusicians and dancers thought it a unique privilege to come to Bijapur andperform before the king, as he himself was a master of the subject.

Musicians were divided into threecategories:huzuris or great masters who had direct access to the king,darbariswere versatile musicians, but could not match the genius of the Huzuris. In thethird category,shaharis had a sound musical background and were diligentlearners. Newrāgas and compositions came into existence with theking in the assembly, and were passed on to thedarbaris andshahari.All musicians received a salary, land and residential quarters in accordancewith their status.

It is difficult to assess thelong-standing effect of Ibrahim's encouragement to popularize music during histime, but he was a great patron of learning as a whole. Bijapur attracted poets,musicians, painters and Sufi philosophers. TheIbrahim Roja, a royal sepulcher he built for himself, is anarchitectural wonder today, although Navraspur -- his dream city, was destroyedby Malik Ambar, a Mogul general.

Ibrahim called himselfjagadguru(world teacher). He sent several presents to emperorAkbar through Asad Beg, theemperor's emissary, and this included items considered sacred by Hindus andgold coins callednavras sikkā.The inscriptions on the coins were "NavrasMuhar Adilshahi Jagadguru dad Ilahi", which meant, "Navras coin ofAdilshah, the god-bestowed world preceptor." The reaction of Akbar to thesepresents and Ibrahim's self-proclaimed world preceptorship is not known. ButAsad Beg's report only confirms Ibrahim's love for Indian culture and hisobsession with theNavras theory.

Under the Adilshahis, the Dakhini Urdu became more broad-based and received recognition and courtpatronage8. It is believed that Bijapur is the birthplace of themushairā,an immensely popular soiree of poetic composition of later times. The newlanguage became popular not only with kings and nobles but with scholars,teachers and commoners as well, andmushairās helped the spread ofliterature, along with sophisticated entertainment. Participation of theaudience is a strong point of themushairā even today. Poets areencouraged by the audience at the completion of every line with exclamationslike "Wah!", "Khub!", "Suban!", "Marhaba!", and "Mukharrar!" For a long time, Persian continued as the court language and Urdu as thespoken language. Under the Adilshahis, Urdu replaced Persian as a medium forliterary and communicative purposes.

The Asari Mahal (see picture no. 99) grew into a magnificent library of Persian and Arabic classics over theyears. It is said thatAurangzeb took all the most valuable manuscripts away incartloads after he conquered Bijapur in 1686 C.E. When James Fergusson visitedAsari Mahal in the 1890s, the remnants were still there, "precious to the persons in charge of the building, who show them with mournful pride and regret."8

In Mysore, known as heart ofKarnataka, Persian and Urdu began to take root duringHyder Ali and TipuSultan's time (1761-1799 C.E.). Tippu Sultan saw that every village had amasjidand amakhtāb. Hyder Ali was a soldier and a statesman but was uneducated. His sonTippu Sultanhowever, was well-read and took special interest in the sciences. In the latterpart of his rule, Persian replaced Kannada as the court language and was givenspecial status in schools.

![]()

Except for Ibn Batuta's account, we do not have any records of Muslim women attending publicschools, but they certainly received the necessary basic education at homes inmohallāsof the rich, as was the practice in medieval times. Elderlymoulvis andnurses were employed to teach them. Daughters of nobles were taught reading andrecitation of holy texts, embroidery, painting, indoor games and calligraphy.

Palace-women received allessential training befitting royalty. Persian and Arabic, arithmetic, music,painting, drawing and Unani medicine were some of the subjects taught.ChivalrousChand Bibi, the princess of Ahmednagar and queen of Ali Adil Shah I,(1557-1580 C.E.) received military training like any of the Muslim princes. Thisenabled her to fight the Mughal army. She also knew Arabic, Persian and Turkish.She playedsitār, andpainting flowers was her hobby. She learned Marathi and Kannada and played avery important role as a regent during the childhood of Ibrahim Adil Shah II.

Hyder Ali obtained severalbeautiful girls from Lahore, Abdala, Kabul, Kandahar, Kashmir and Gujarat for hisZenana. He had them trained in dancing, singing and playing various musicalinstruments under the stewardship of Kuppayya, who was master of Bharatanatyashāstraand in charge of the royal theater9. Some painted panels inDariyaDaulat constructed during Tippu's time depict women playing musicalinstruments. It is likely that Tippu Sultan continued the system of traininggirls, that was started by his father.

![]()

Kamat Reference Database

Kamat Reference Database Electronic Books

Electronic Books Education in Karnataka through the Ages

Education in Karnataka through the Ages Islamic Education System in India

Islamic Education System in India