| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/oldworlditswaysd00bryarich |

BY

DESCRIBING

A TOUR AROUND THE WORLD

AND

JOURNEYS THROUGH EUROPE

ST. LOUIS

The Thompson Publishing Company

1907

Copyright 1907

By William Jennings Bryan

This volume is published in response to numerous requests from manysections, and my purpose is to put in permanent and convenient form theobservations made during travels in the old world.

The illustrations will throw light on the subjects treated and it is believedwill add much to the interest. The photographs from which they were madewere collected at the places visited or taken by members of our party. Chaptersone to forty-six were written from time to time during the trip around theworld.

I was accompanied on this tour by my wife and our two younger children,William J., Jr., and Grace, aged sixteen and fourteen years respectively. Thetrip was taken for educational purposes and proved far more instructive thanwe anticipated.

We left our home September 21, 1905, sailed from San Francisco September27, and arrived in New York August 29, 1906—the day before the datefixed for the home-coming reception in that city—and reached Lincoln September5, sixteen days less than a year after our departure.

While most of our travel was in the North Temperate Zone, we werebelow the Equator a few days in Java and above the Arctic Circle in Norway.

In this narrative I fear I have sacrificed literary style to conciseness, for Ihave endeavored to condense and crowd into the space as much information aspossible. The statement of facts may be relied on, being based either uponobservations gathered at first hand from persons worthy to be trusted, or takenfrom authoritative writings.

Mrs. Bryan assisted me in the collection of materials and the preparation ofthe matter, and I am also indebted to the American Ambassadors, Ministers andConsuls, as well as to the officials of the countries which were visited, for valuableinformation.

I have included a series of articles written during a former visit to Europein 1902. As I have avoided in the World Tour Narratives the subjects treatedin these previous European articles, the two series are appropriately publishedtogether.

All of these are published with the more pleasure because I believe theywill give the reader increased admiration for American institutions and a largerconfidence in the triumph of American Ideals.

WILLIAM JENNINGS BRYAN

Lincoln, Nebraska, 1907

| Author's Preface | 5 |

| Chapter I—Crossing the Pacific—Hawaii | 15 |

| Chapter II—Japan and Her People | 25 |

| Chapter III—Japanese Customs and Hospitality | 37 |

| Chapter IV—Japan—Her History and Progress | 49 |

| Chapter V—Japan—Her Industries, Arts and Commerce | 61 |

| Chapter VI—Japan—Her Educational System and Her Religions | 69 |

| Chapter VII—Japan—Her Government, Politics and Problems | 80 |

| Chapter VIII—Korea—"The Hermit Nation" | 90 |

| Chapter IX—China—As She Was | 101 |

| Chapter X—China—As She Was—Part Second | 112 |

| Chapter XI—Chinese Education, Religion and Philosophy | 119 |

| Chapter XII—China's Awakening | 127 |

| Chapter XIII—Chinese Exclusion | 137 |

| Chapter XIV—The Philippines—The Northern Islands | 151 |

| Chapter XV—The Philippines—The Moro Country | 177 |

| Chapter XVI—The Philippine Problem | 186 |

| Chapter XVII—The Philippine Problem—Continued | 197 |

| Chapter XVIII—Java—The Beautiful | 205 |

| Chapter XIX—Netherlands India | 215 |

| Chapter XX—In The Tropics | 223 |

| Chapter XXI—Burma and Buddhism | 234 |

| Chapter XXII—Eastern India | 247 |

| Chapter XXIII—Hindu India | 260 |

| Chapter XXIV—Mohammedan India | 273 |

| Chapter XXV—Western India | 285 |

| Chapter XXVI—British Rule in India | 295 |

| Chapter XXVII—Ancient Egypt | 312 |

| Chapter XXVIII—Modern Egypt | 321 |

| Chapter XXIX—Among the Lebanons | 331 |

| [viii]Chapter XXX—The Christian's Mecca | 341 |

| Chapter XXXI—Galilee | 349 |

| Chapter XXXII—Greece, the World's Teacher | 358 |

| Chapter XXXIII—The Byzantine Capital | 366 |

| Chapter XXXIV—In the Land of the Turk | 376 |

| Chapter XXXV—Hungary and Her Neighbors | 385 |

| Chapter XXXVI—Austria-Hungary | 396 |

| Chapter XXXVII—The Duma | 403 |

| Chapter XXXVIII—Around the Baltic | 417 |

| Chapter XXXIX—Democratic Norway | 425 |

| Chapter XL—England's New Liberal Government | 435 |

| Chapter XLI—Homes and Shrines of Great Britain | 445 |

| Chapter XLII—Glimpses of Spain | 456 |

| Chapter XLIII—A Word to Tourists | 464 |

| Chapter XLIV—American Foreign Missions | 470 |

| Chapter XLV—World Problems | 478 |

| Chapter XLVI—A Study of Governments | 485 |

| Chapter XLVII—The Tariff Debate in England | 492 |

| Chapter XLVIII—Ireland and Her Leaders | 498 |

| Chapter XLIX—Growth of Municipal Ownership | 504 |

| Chapter L—France and Her People | 510 |

| Chapter LI—The Republic of Switzerland | 521 |

| Chapter LII—Three Little Kingdoms—Denmark | 525 |

| Chapter LIII—Belgium | 527 |

| Chapter LIV—The Netherlands | 529 |

| Chapter LV—Germany and Socialism | 533 |

| Chapter LVI—Russia and Her Czar | 542 |

| Chapter LVII—Rome—The Catholic Capital | 549 |

| Chapter LVIII—Tolstoy, The Apostle of Love | 559 |

| Chapter LIX—Notes on Europe | 567 |

| PAGE | |

| William Jennings Bryan | Frontispiece |

| Leaving San Francisco on the Manchuria | 16 |

| Surf-Riding in Hawaii | 19 |

| Our Party | 21 |

| Hawaiian Foliage | 24 |

| A Picturesque View | 26 |

| At Miyanoshita | 29 |

| A Japanese Family | 31 |

| Dwarf Maple—50 years old | 36 |

| Japanese Geisha Girls | 38 |

| Yukio Ozaki—Mayor of Tokyo | 40 |

| In Count Okuma's Conservatory | 43 |

| Marquis Ito | 44 |

| Count Okuma | 45 |

| The Guest of Gov. Chikami at Kagoshima | 50 |

| Japanese Lady in American Dress | 53 |

| A Japanese Maiden | 54 |

| Yukichi Fukuzawa, Jr. | 57 |

| Sumitka Haseba—Japanese Statesman | 59 |

| Japanese Water-Carrier | 64 |

| A Visit to Count Okuma's School near Tokyo | 70 |

| Japanese Stone Lantern | 74 |

| Korean Lion—Yes | 75 |

| Korean Lion—No | 75 |

| In Front of Nikko Temple—Japan | 76 |

| Admiral Togo | 82 |

| President of Diet—Japan | 84 |

| Baron Kentaro Kaneko | 85 |

| Mr. Okura, a Successful Japanese Business Man | 87 |

| A Shinto Gate at Nara | 89 |

| Two Korean Families | 91 |

| In Korea—Group of Natives | 92 |

| A Korean Scene | 95 |

| American Hospital at Seoul—Korea | 99 |

| Doing the Family Washing | 100 |

| A Group of Chinese—Pekin | 103 |

| The Wall at Pekin | 105 |

| A Street in Pekin | 107 |

| Chinese Emperor | 108 |

| The Father of the Chinese Emperor | 109 |

| Empress Dowager—China | 110 |

| One of the Principal Streets of Pekin | 111 |

| House Boats at Canton | 114 |

| Yuan Shi Kai—Viceroy Tientsin and Pekin | 117 |

| Altar of Heaven—Pekin | 123 |

| Illustration of Foot-Binding | 125 |

| Traveling: in North China | 126 |

| Viceroy Chang Chih Tung | 129 |

| Wu Ting Fang | 130 |

| Chinese Cart at Pekin | 133 |

| [x]Chou Fu, Viceroy of Nanking | 134 |

| A Canton Bridge | 136 |

| Manchu and Chinese Women—China | 139 |

| The Chinese Wheelbarrow | 143 |

| Fashionable Conveyance at Hong Kong | 147 |

| Colossal Statue of Ming, Ruler of China | 150 |

| A Filipino Village | 152 |

| Filipino Houses | 153 |

| General Emilio Aguinaldo | 154 |

| Filipino Boys with Blow Guns | 155 |

| Group of Filipinos | 156 |

| In the Philippines | 157 |

| The Accomplished Wife of a Filipino Official | 159 |

| Filipino Night School—American Teachers | 161 |

| A Filipino Belle | 165 |

| Emilio Aguinaldo, Mother, Sister, Brother and Son | 167 |

| A Filipino Teacher | 169 |

| Hauling Hemp | 170 |

| Moro Huts | 176 |

| Threshing Rice | 176 |

| Moros | 182 |

| Moro School—Zamboanga | 185 |

| Henry C. Ide, Gov. Gen. Philippine Islands | 187 |

| Datu Piang and Grandson | 188 |

| Dr. G. Apacible | 191 |

| Plowing in Sulu Land | 193 |

| Sailing in Manila Bay | 195 |

| Carabao Cart and Driver | 198 |

| Harvesting Sugar Cane | 199 |

| The Rice Harvest | 200 |

| A Driveway in Botanical Garden—Buitenzorg | 206 |

| Extinct Volcano, Salak | 207 |

| A Java Road | 210 |

| Temple at Boro Boedoer | 213 |

| A Native | 216 |

| A Group of Javanese | 219 |

| In the Tropics | 224 |

| The Lake at Kandy, Ceylon | 226 |

| Singalese Chief's Daughter—Showing Jewelry | 228 |

| Singalese Carpenter | 229 |

| Tamil Girl—Ceylon | 231 |

| An Elephant at Work in Rangoon | 235 |

| The Park at Rangoon | 236 |

| Five Hundred Pagoda at Mandalay | 237 |

| Burmese Woman with Cigarette | 238 |

| Buddhist Temple | 239 |

| The Shwe Dagon Pagoda | 240 |

| Burmese Family | 242 |

| Gathering Precious Stones in Burma | 245 |

| Bronze Image of Buddha, Built 1252 | 246 |

| Calcutta Burning Ghat | 248 |

| The Maharaja of Mourbharag—An Indian Prince | 250 |

| Indian Princess | 251 |

| The Great Banyan Tree—Calcutta | 252 |

| A Calcutta Street—India | 253 |

| Keshub Chunder Sen | 255 |

| The Bull Cart in India | 256 |

| Thibetans, as Seen at Darjeeling | 257 |

| View of the Himalayas, as seen from Darjeeling | 258 |

| [xi]The Camel in India | 261 |

| Cultivating Psychic Power on Spikes at Benares, India | 262 |

| Bathing Ghat on the Ganges | 263 |

| Pundit Sakharam Ganesh | 264 |

| Hindu Types | 266 |

| Hindu Fair at Allahabad—India | 267 |

| Hindu Fakir | 268 |

| Mrs. Besant's College | 269 |

| A Gala Day in India | 270 |

| Cremation of Dead Bodies—Burning Ghat | 271 |

| Hindu Group | 272 |

| Angel of the Resurrection | 274 |

| The Honorable My Justice Badruddin Tyabji | 275 |

| Ruins of the Residency—Lucknow, India | 276 |

| Pearl Mosque at Delhi | 277 |

| Gokale—Prominent Indian Reformer | 278 |

| A Pool at Lucknow—India | 279 |

| Mohammedans at Prayer | 280 |

| Klanjiban Ganguli, Supt. Instruction | 281 |

| Taj Mahal, Agra | 283 |

| Street in Jaipore—India | 287 |

| An American Maid in Parsee Costume | 290 |

| Maharaja—Jaipore | 291 |

| Mohammedan Lady, Bombay | 292 |

| Elephant Parade | 293 |

| Assembling for the Bombay Meeting | 294 |

| His Excellency the Earl of Minto | 296 |

| Viceroy's Palace at Calcutta | 298 |

| Sir James Diggs La Touche | 300 |

| Sir Andrew Frazer | 302 |

| Lord Curzon | 303 |

| Gov. Lamington—Bombay, India | 307 |

| Indian Students | 309 |

| Famous Asoka Pillar | 311 |

| Karnak Temple | 313 |

| Mummy and Wooden Statue | 314 |

| The Pyramid and the Sphinx | 319 |

| A Sphinx | 320 |

| Climbing the Pyramids | 322 |

| The Ostrich Farm near Cairo | 323 |

| Egyptian Ladies | 324 |

| An Egyptian Merchant | 325 |

| Khedive of Egypt | 328 |

| Reunion on the Desert | 329 |

| Temple at Baalbek | 332 |

| The Giant Stone at Baalbek | 334 |

| Cedars of Lebanon | 336 |

| Beyrouth—Syria | 337 |

| The Big Tail Sheep | 338 |

| Damascus Dogs | 339 |

| Mount of Olives | 344 |

| Wailing Place of the Jews | 346 |

| A Jewish Rabbi | 347 |

| A Bedouin | 351 |

| At Breakfast | 352 |

| An Arab Maiden | 353 |

| The Bedouin Shepherd and His Flock | 354 |

| Salim Moussa, with Party of Tourists | 355 |

| Mary's Well at Nazareth | 356 |

| [xii]The Parthenon | 359 |

| The Acropolis at Athens | 360 |

| Mars Hill | 362 |

| Demosthenes' Platform | 363 |

| Frieze of the Parthenon. | 365 |

| St. Sofia at Constantinople | 367 |

| The Bosphorus at Constantinople | 369 |

| Smoking the Hubble-Bubble Pipe | 371 |

| Robert's College near Constantinople | 373 |

| At the World's Breakfast Table | 375 |

| Sons of the Sultan. | 378 |

| Turkish Officials | 381 |

| The Danube and Parliament Building—Budapest | 387 |

| A Street in Budapest | 388 |

| Budapest | 391 |

| Prime Minister Wekerle—Hungary | 393 |

| Count Apponyi | 394 |

| Minister Kossuth | 395 |

| Carlsbad | 399 |

| Count Ignatieff | 404 |

| The Palace Where the Russian Duma Meets | 405 |

| Prof. Serge Murmetzeff | 407 |

| Editor Paul I. Miliukoff | 408 |

| Some Members of Russian Duma | 410 |

| Members of the Russian Duma | 411 |

| Maxim Winawer | 412 |

| Group of Russian Duma with Mr. Bryan in Center | 413 |

| Ivan Petrunkevich | 415 |

| A View of Stockholm | 418 |

| King Oscar of Sweden | 420 |

| The Viking Ship at Christiania | 426 |

| In Hjorendfiord | 427 |

| Troldfjord | 428 |

| Ole Bull | 430 |

| King Haakon and Queen Maud | 433 |

| King Edward VII | 436 |

| Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman | 438 |

| House of Parliament, London | 439 |

| John Morley, M. P. | 441 |

| John Burns | 443 |

| Melrose Abbey | 446 |

| Birthplace of Robert Burns | 449 |

| Shakespeare's Birth-House Restoration | 450 |

| Hawarden Castle—Home of Gladstone | 453 |

| W. E. Gladstone | 454 |

| Windsor Castle | 455 |

| The Old Bridge at Cordova | 458 |

| The Alhambra—Spain | 461 |

| Resignation | 463 |

| Vesuvius as Seen from Naples | 466 |

| Mission School | 477 |

| Four Statesmen of England | 493 |

| Irish Patriots | 499 |

| Charles S. Parnell | 502 |

| Meeting of the Waters—Killarney | 503 |

| The Broomelaw Bridge at Glasgow | 505 |

| Napoleon Bonaparte | 511 |

| Napoleon Bonaparte Crowning Josephine. | 514 |

| Avenue Champs-Elysees—Paris | 516 |

| [xiii]Tomb of Napoleon | 518 |

| King Christian and Wife | 526 |

| Palace of Justice—Belgium | 527 |

| The Hague | 529 |

| The Market Place at Amsterdam | 530 |

| A Netherlands Statesman | 531 |

| A Dutch Windmill | 532 |

| The Reichstag | 533 |

| Leipsic University | 534 |

| The Rhine | 536 |

| Kaiser Wilhelm | 538 |

| Breton Peasants | 540 |

| The Czar of Russia | 543 |

| Russian Beggar | 547 |

| Kremlin of Moscow | 548 |

| Coliseum—Rome | 550 |

| Pope Pius X | 551 |

| Naples | 553 |

| Grand Canal—Venice | 555 |

| St. Peter's at Rome | 557 |

| Madonna | 558 |

| Count Tolstoy | 560 |

| Goddess of Liberty—New York Harbor | 575 |

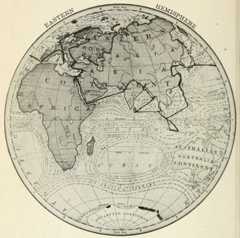

ROUTE TRAVELED.

There is rest in an ocean voyage. The receding shores shut out thehum of the busy world; the expanse of water soothes the eye by its veryvastness; the breaking of the waves is music to the ear and there ismedicine for the nerves in the salt sea breezes that invite to sleep. Atfirst one is disturbed—sometimes quite so—by the motion of the vessel,but this passes away so completely that before many days the dippingof the ship is really enjoyable and one finds a pleasure inascending the hills and descending the valleys into which the decksometimes seems to be converted.

If one has regarded the Pacific as an unknown or an untraversedsea, the impression will be removed by a glance at a map recently publishedby the United States government—a map with which everyocean traveler should equip himself. On this map the Pacific iscovered with blue lines indicating the shortest routes of travelbetween different points with the number of miles. The first thing thatstrikes one is that the curved line indicating the northern routebetween San Francisco and Yokohama is only 4,536 miles long, whilethe apparently straight line between the two points is 4,791 miles long—thedifference being explained by the curvature of the earth,although it is hard to believe that in following the direct line a shipwould have to climb over such a mountain range of water, so to speak,as to make it shorter to go ten degrees north. The time between theUnited States and the Japanese coast has recently been reduced to lessthan eleven days, but the northern route is not so pleasant at thisseason of the year, and we sailed on the Manchuria, September 27,going some twenty degrees farther south via Honolulu. This routecovers 5,545 miles and is made in about sixteen days when the weatheris good.

The Manchuria is one of the leviathans of the Pacific and is ownedby Mr. Harriman, president of the Union Pacific and Southern PacificRailways. The ship's crew suggests the Orient, more than three-fourths[16]being Chinese, all wearing the cue and the national garb.There is also a suggestion of the Orient in the joss house and opiumden of the Chinese in the steerage.

In crossing the one hundred and eightieth meridian we lost a day,and as we are going all the way around, we cannot recover it as thosecan who recross the Pacific. We rose on Saturday morning, October 7,and at nine o'clock were notified that Sunday had begun and theremainder of the day was observed as the Sabbath (October 8).

According to the chart or map referred to there are threecenters of ocean traffic in the Pacific. Honolulu, the most importantof all, the Midway Islands, 1,160 miles northwest of Honolulu, andthe Samoan Islands, some twenty-two hundred miles to the south.The Society Islands, about the same distance to the southeast of Honolulu,and Guam, some fifteen hundred miles from the mainland ofAsia, are centers of less importance.

Our ship reached Honolulu early on the morning of the sixth dayout and we had breakfast on the island. The Hawaiian Islands (inhabited)number eight and extend from the southeast to the northwest,covering about six degrees of longitude and nearly four of latitude.Of these eight islands, Hawaii, the southernmost one, is the largest,having an area of 4,200 square miles and a population of nearlyfifty thousand. Hilo, its chief city, situated on the east shore, is thesecond Hawaiian city of importance and contains some seven thousand[17]inhabitants. The island of Oahu, upon which Honolulu is situated,is third in size but contains the largest population, almost sixtythousand, of which forty thousand dwell in or near the capital. Theislands are so small and surrounded by such an area of water as toremind one of a toy land, and yet there are great mountains there, onepiercing the clouds at a height of 14,000 feet. Immense cane fieldsstretch as far as the eye can reach, and busy people of different colorsand races make a large annual addition to our country's wealth. Onone of the islands is an active volcano which furnishes a thrillingexperience to those who are hardy enough to ascend its sides and crossthe lava lake, now grown cold, which surrounds the present crater.Each island has one or more extinct volcanoes, one of these, called"The Punch Bowl," being within the city limits of Honolulu. On oneof the islands is a leper colony, containing at times as many as athousand of the afflicted. During campaigns the spellbinders addressthe voters from boats anchored at a safe distance from the shore.

As the Manchuria lay at anchor in the harbor all day the passengerswent ashore and, dividing into groups, inspected the various placesof interest. By the aid of a reception committee, composed of democrats,republicans and brother Elks, we were able to crowd a greatdeal of instruction and enjoyment into the ten hours which we spentin Honolulu. We were greeted at the wharf with the usual salutation,Aloha, a native word which means "a loving welcome," and weredecorated with garlands of flowers for the hat and neck. While thesegarlands or leis (pronounced lays) are of all colors, orange is thefavorite hue, being the color of the feather cloak worn by the Hawaiiankings and queens in olden times. The natives are a very kindlyand hospitable people, and we had an opportunity to meet someexcellent specimens of the race at the public reception and the countryresidence of Mr. Damon, one of the leading bankers of the island.

When the islands were discovered in 1778 by Captain Cook, thenatives lived in thatched huts and were scantily clothed, after themanner of the tropical races. They were not savages or cannibals, butmaintained a degree of civil order and had made considerable progressin the primitive arts. In their religious rites they offered human sacrifices,but they welcomed the white man and quickly embracedChristianity. American influence in the islands reaches back someseventy-five years, beginning with New England missionaries, manyof whose descendants have made permanent homes here. Some ofthese, mingling their blood with the blood of the natives, form connectinglinks between the old and the new civilization. Foreign ways[18]and customs soon began to manifest themselves and long before annexationthe native rulers built buildings after the style of our ownarchitecture. The Capitol building, erected twenty years ago for theking's palace, is an imposing structure, and the Judiciary buildingis almost equal to it. The parks and public grounds are beautiful andwell kept, and the business blocks commodious and substantial. Inshort, Honolulu presents the appearance of a well built, cleanly andprosperous American city, with its residences nestling among palmtrees and tropical plants. Good hotels are abundant. The AlexanderYoung hotel is built of stone imported from the States and would docredit to a city of half a million. The Royal Hawaiian hotel, evenmore picturesque, though not so large, and the Moana hotel, at thebeach, vie with the Young in popularity.

The program for our day's stay began with a seven mile automobileride to the Pali, the pass over which the natives cross to the fartherside of the island. The road is of macadam and winding along a picturesquevalley rises to a height of about 1,200 feet. At this point theeye falls upon a picture of bewitching beauty. Just below is aprecipitous cliff over which a conquering king, Kamehameha the First,about one hundred and ten years ago, drove an opposing army whenhe established himself as ruler of the islands. To the east from thefoot of the cliff, a thousand feet down, stretches a beautiful valley withan endless variety of verdure; and beyond, a coast line broken bya rocky promontory, around whose base the waters reflect from theirvarying depths myriad hues of blue and green. There are ocean viewsof greater expanse, mountain views more sublime and agriculturallandscapes more interesting to a dweller upon prairies, but it is doubtfulwhether there is anywhere upon earth a combination of mountain,valley and ocean—a commingling of the colors of sky and sea androck and foliage—more entrancing. Twice on the way to Pali wepassed through mountain showers and were almost ready to turn back,but the members of the committee, knowing of the rare treat ahead,assured us that Hawaiian showers were of short duration and "extradry." When we at last beheld the view, we felt that a drenching mightgladly have been endured, so great was the reward.

The committee next took us by special train on the Oahu railroad toone of the great sugar plantations of the island, a plantation outsideof the trust, owned and operated by a San Francisco company. Thiscompany has built an immense refinery upon the plantation and themanager showed us the process of sugar making from the crushingof the cane to the refined product, sacked ready for shipment.

The stalks, after passing through the mill, are dried and carried tothe furnace, thus saving some sixty-five per cent of the cost of fuel—animportant economy when it is remembered that all the fuel formanufacturing is brought from abroad. Until recently, several hundredthousand dollars' worth of coal was annually brought from Australia,but California oil is now being substituted for coal. The refusewhich remains when the sugar making process is completed is returnedto the land as fertilizer. The economies effected in fuel and in fertilizer,together with the freight saved on impurities carried in the rawsugar, amount to a considerable sum and to this extent increase theprofit of the business. While at the sugar plantation we were shownan immense pumping plant used in the irrigation of the land. Thewater is drawn from artesian wells and forced to a height of almostsix hundred feet, in some places, and from the summits of the hillsis carried to all parts of the plantation. Some idea of the size of theplants can be gathered from the fact that the pumps used on thisplantation have a combined capacity of sixty million gallons per day.

Speaking of irrigation, I am reminded that the rainfall varies greatlyin different parts of the island. At Honolulu, for instance, it is somethinglike thirty inches per year, while at one point within five milesof the city the annual rainfall sometimes reaches one hundred andforty inches. The sugar plantation visited, while one of the largest,is only one of a number of plantations, the total sugar product of theislands reaching about four hundred thousand tons annually.

Next to the sugar crops comes the rice crop, many of the rice fields[20]lying close to the city. Pineapples, bananas, coffee and cocoanuts arealso raised. Attention is being given now to the development of cropswhich can be grown by small planters, those in authority recognizingthe advantage to the country of small holdings.

The labor problem is the most serious one which the people ofHawaii have to meet. At present the manual labor is largely done byJapanese, Chinese and Koreans—these together considerably outnumberingthe whites and natives. Several thousand Portuguese have beenbrought to the islands and have proven an excellent addition to thepopulation. On the day that we were there the immigration commissionauthorized the securing of a few Italian families with a view oftesting their fitness for the climate. The desire is to develop a homogeneouspopulation suited to the conditions and resources of the islands.

We returned from the sugar plantation in automobiles, stopping atthe country home of Mr. Damon, which was once a royal habitation.The present owner has collected many relics showing the life, habitsand arts of the native Hawaiians.

Still nearer the town we visited two splendid schools, one for nativeboys, the other for native girls, built from the funds left by nativechiefs. The boys and girls were drawn up in front of one of thebuildings and under the direction of their instructor sang the nationalanthem of the natives, now preserved as the territorial hymn. Theywere a finely proportioned, well dressed and intelligent group and aresaid to be studious and excellently behaved. Nothing on the islandsinterested us more than these native children, illustrating as they do,not only the possibilities of their race, but the immense progress madein a little more than a hundred years of contact with the whites. Themuseum, the gift of Mr. Bishop, now of California, who married thewidow of one of the native chiefs, is said to contain the best collectionof the handiwork of the natives of the Pacific Islands to be found anywhere.

The public reception at the Royal Hawaiian hotel gave us an opportunityto meet not only the prominent American and native citizensand their wives, but a large number of the artisans and laborers of thevarious races, and we were pleased to note throughout the day the harmoniousfeeling which exists between the whites and the brown population.

Political convictions produce the same results here as in the UnitedStates, sometimes dividing families. For instance, Prince Cupid, thepresent territorial representative in congress, is a republican, while hisbrother, Prince David, is an enthusiastic democrat.[21]

[22]The luncheon prepared by the committee included a number ofnative dishes cooked according to the recipes which were followed forhundreds of years before the white man set foot upon the island. Thehealth of the guests was drunk in cocoanut water, a nut full of whichstood at each plate. Poi, the staple food of the natives, was present inabundance. This is made from a root or tuber known as taro, whichgrows in swamps and has a leaf resembling our plant, commonly knownas elephant's ear. This tuber is ground to a pulp resembling paste andis served in polished wooden bowls, in the making of which the nativesexhibit great skill. Next in interest came the fish and chicken, wrappedin the leaves of a plant called ti (pronounced like tea) and cookedunderground by means of hot stones. The flavor of food thus cookedis excellent. The crowning glory of the feast was a roasted pig, alsocooked underground—and a toothsome dish it was. Besides these, therewere bread fruit, alligator pears and delicacies made from the meatof the cocoanut. The salt, a native product, was salmon colored. Theinvited guests were about equally divided between the American andnative population. But for the elegant surroundings of the Younghotel, the beautifully appointed table and the modern dress, it was sucha dinner as might have been served by the natives to the whites onthe first Thanksgiving after the New England missionaries landed.

After a call upon Governor Carter, a descendant of the third generationfrom missionary stock, we visited the aquarium. When wenoticed on the printed program that we were scheduled for a visit tothis place, it did not impress us as possessing special interest, but wehad not been in the building long before we were all roaring withlaughter at the remarkable specimens of the finny tribe here collected.

Language can not do this subject justice. No words can accuratelyportray what one here sees. The fish are odd in shape and have all thehues of the rainbow. The tints are laid on as if with a brush andyet no painter could imitate these—shall we call them "pictures in watercolor?" Some were long and slim; some short and thick. One had aforehead like a wedge, another had a very blunt nose. Some lookedlike thin slabs of pearl with iridescent tints; others had quills like aporcupine. One otherwise respectable looking little fellow had a longnose upon the end of which was a fiery glow which made him looklike an old toper; another of a deep peacock blue had a nose for allthe world like a stick of indigo which it wiggled as it swam.

There were convict fish with stripes like those worn in penitentiariesand of these there were all sizes; some moving about slowly and solemnlylike hardened criminals and others sporting about as if enjoying[23]their first taste of wrongdoing. One variety wore what looked like anorange colored ribbon tied just above the tail; the color was so likethe popular flower of Hawaii that we were not surprised to find thatthe fish was called the lei. In one tank the fish had a habit of restingupon the rocks; they would brace themselves with their fins and watchthe passersby. At one time two were perched side by side and recalledthe familiar picture of Raphael's Cherubs. Besides the fishes there werecrabs of several varieties, all brilliant in color; one called the hermitcrab had a covering like velvet, with as delicate a pattern as ever camefrom the loom. And, then, there was the octopus with the under sideof its arms lined with valve-like mouths. It was hiding under therocks, and when the attendant poked it out with a stick, it darkenedthe water with an inky fluid, recalling the use made of the subsidizedAmerican newspapers by the trust when attacked.

No visitor to Honolulu should fail to see the aquarium. Every effortto transport these fish has thus far failed. To enjoy the dudes, clownsand criminals of fishdom one must see them in their native waters.

The tour of the island closed with a trip to the beach and a ride inthe surf boats. The native boat is a long, narrow, deep canoe steadiedby a log fastened at both ends to the boat and floating about ten feetfrom the side. These canoes will hold six or seven persons and arepropelled by brawny-armed natives. Our party clad themselves inbathing suits and, filling three canoes, were rowed out some distancefrom the shore. The natives, expert at this sport, watch for a large waveand signal each other when they see one approaching, and then withtheir big round paddles they start their canoes toward the land. Asthe wave raises the stern of the canoe, they bend to their work, thepurpose being to keep the canoe on the forward slope of the wave. Itis an exciting experience to ride thus, with the spray breaking overone while the canoe flies along before the wave. Sometimes the boatmenare too slow and the wave sweeps under the canoe and is gone,but as a rule they know just how fast to work, and there is greatrivalry between the surf riders when two or more crews are racing. Itis strange that a form of sport so delightful has not been transportedto the American seaside resorts. There is surf bathing the year roundat Honolulu and few beaches can be found which can compare withWaikiki.

The Oahu railroad, which carried us out to the sugar plantation,and which has seventy miles of track on the island, passes within sightof the Pearl harbor, which is the only large inlet in the islands capableof being developed into a harbor. The United States government is[24]already dredging this harbor and preparing it for both naval and commercialuses. The Hawaiian Islands occupy a strategic position as wellas a position of great commercial importance, and as they are on a directline between the Isthmus of Panama and the Orient, their value as amid-ocean stopping place will immeasurably increase. The islandsbeing now United States territory, the advantage of the possession ofPearl harbor is accompanied by a responsibility for its proper improvement.No one can visit the harbor without appreciating its importanceto our country and to the world.

When we departed from the wharf at nightfall to board the Manchuriawe were again laden with flowers, and as we left the island, refreshedby the perfume of flowers and cheered by songs and farewells,we bore away grateful memories of the day and of the hospitality ofthe people. Like all who see this Pacific paradise, we resolved toreturn sometime and spend a part of a winter amid its beauties.

The eyes of the world are on Japan. No other nation has evermade such progress in the same length of time, and at no time in herhistory has Japan enjoyed greater prestige than she enjoys just now;and, it may be added, at no time has she had to face greater problemsthan those which now confront her.

We were fortunate in the time of our arrival. Baron Komura, thereturning peace commissioner, returned two days later; the naval reviewcelebrating the new Anglo-Japanese alliance took place in Yokohamaharbor a week afterward, and this was followed next day by thereception of Admiral Togo at Tokyo. These were important eventsand they gave a visitor an extraordinary opportunity to see the peopleen masse. In this article I shall deal in a general way with Japanand her people, leaving for future articles her history, her government,her politics, her industries, her art, her education and her religions.

The term Japan is a collective title applied to four large islands, thatis, Honshiu, Kyushu, Shikoku, Hokkaido and about six hundredsmaller ones. Formosa and the islands immediately adjoining it arenot generally included, although since the Chinese war they belongto Japan.

Japan extends in the shape of a crescent, curving toward the northeast,from fifty north latitude and one hundred and fifty-six east longitudeto twenty-one degrees north latitude and one hundred and nineteeneast longitude. The area is a little less than one hundred and sixtythousand square miles, more than half of which is on the islandof Honshiu. The coast line is broken by numerous bays furnishingcommodious harbors, the most important of which are at Yokohama,Osaka, Kobe, Nagasaki, Kagoshima and Hakodate. The islands areso mountainous that only about one-twelfth the area is capable ofcultivation. Although Formosa has a mountain, Mt. Niitaka (sometimescalled Mt. Morrison) which is two thousand feet higher,[26]Fujiyama is the highest mountain in Japan proper. It reaches a heightof 12,365 feet.

Fuji (Yama is the Japanese word for mountain) is called the SacredMountain and is an object of veneration among the Japanese. Andwell it may be, for it is doubtful if there is on earth a more symmetricalmountain approaching it in height. Rising in the shape of aperfect cone, with its summit crowned with snow throughout nearly theentire year and visible from sea level, it is one of the most sublimeof all the works of nature. Mt. Ranier, as they say at Seattle, orTacoma, as it is called in the city of that name, and Popocatapetl, nearMexico's capital, are the nearest approach to Fuji, so far as the writer'sobservation goes. Pictures of Fuji are to be found on everything; theyare painted on silk, embroidered on screens, worked on velvet, carvedin wood and wrought in bronze and stone. We saw it from Lake[27]Hakone, a beautiful sheet of water some three thousand feet above theocean. The foot hills which surround the lake seem to open at onepoint in order to give a more extended view of the sloping sides of thissleeping giant.

And speaking of Hakone, it is one of the beauty spots of Japan.On an island in this lake is the summer home of the crown prince.Hakone is reached by a six-mile ride from Miyanoshita, a picturesquelittle village some sixty miles west of Yokohama. There are here hotsprings and all the delights of a mountain retreat. One of the bestmodern hotels in Japan, the Fujiya, is located here, and one of itsearliest guests was General Grant when he made his famous tour aroundthe world. The road from the hotel to Hakone leads by foamingmountain streams, through closely cultivated valleys and over a rangefrom which the coast line can be seen.

Nikko, about a hundred miles north of Tokyo, and Nara about thirtymiles from Kyoto, are also noted for their natural scenery, but as theseplaces are even more renowned because of the temples located therethey will be described later. The inland sea which separates the largerislands of Japan, and is itself studded with smaller islands, adds interestto the travel from port to port. Many of these islands are inhabited,and the tiny fields which perch upon their sides give evidence of anever present thrift. Some of the islands are barren peaks jutting a fewhundred feet above the waves, while some are so small as to look likehay stacks in a submerged meadow.

All over Japan one is impressed with the patient industry of thepeople. If the Hollanders have reclaimed the ocean's bed, the peopleof Japan have encroached upon the mountains. They have broadenedthe valleys and terraced the hill sides. Often the diminutive fields areheld in place by stone walls, while the different levels are furnishedwith an abundance of water from the short but numerous rivers.

The climate is very much diversified, ranging from almost tropicalheat in Formosa to arctic cold in the northern islands; thus Japan canproduce almost every kind of food. Her population in 1903 was estimatedat nearly forty-seven millions, an increase of about thirteenand a half millions since 1873. While Tokyo has a population ofabout one and a half millions, Osaka a population of nearly a million,Kyoto three hundred and fifty thousand, Yokohama three hundredthousand, and Kobe and Nagoya about the same, and there are severalother large cities of less size, still a large majority of the population isrural and the farming communities have a decided preponderance in[28]the federal congress, or diet. The population, however, is increasingmore rapidly in the cities than in the country.

The stature of the Japanese is below that of the citizens of theUnited States and northern Europe. The average height of the menin the army is about five feet two inches, and the average weight betweena hundred and twenty and a hundred and thirty pounds. Itlooks like burlesque opera to see, as one does occasionally, two or threelittle Japanese soldiers guarding a group of big burly Russian prisoners.

The opinion is quite general that the habit which the Japanese formfrom infancy of sitting on the floor with their feet under them, tendsto shorten the lower limbs. In all the schools the children are nowrequired to sit upon benches and whether from this cause or some other,the average height of the males, as shown by yearly medical examination,is gradually increasing. Although undersize, the people aresturdy and muscular and have the appearance of robust health. Incolor they display all shades of brown, from a very light to a verydark. While the oblique eye is common, it is by no means universal.

The conveyance which is most popular is the jinrikisha, a narrowseated, two wheeled top buggy with shafts, joined with a cross pieceat the end. These are drawn by "rikisha men" of whom there areseveral hundred thousand in the empire. The 'rikisha was inventedby a Methodist missionary some thirty years ago and at once spranginto popularity. When the passenger is much above average weight,or when the journey is over a hilly road, a pusher is employed and inextraordinary cases two pushers. It is astonishing what speed thesemen can make. One of the governors informed me that 'rikisha mensometimes cover seventy-five miles of level road in a day. They willtake up a slow trot and travel for several miles without a break. Wehad occasion to go to a village fifteen miles from Kagoshima andcrossed a low mountain range of perhaps two thousand feet. The tripeach way occupied about four hours; each 'rikisha had two pushersand the men had three hours rest at noon. They felt so fresh at theend of the trip that they came an hour later to take us to a dinnerengagement. In the mountainous regions the chair and kago take theplace of the 'rikisha. The chair rests on two bamboo poles and is carriedby four men; the kago is suspended from one pole, like a swinginghammock, and is carried by two. Of the two, the chair is much themore comfortable for the tourist. The basha is a small one-horse omnibuswhich will hold four or six small people; it is used as a sort of stagebetween villages. A large part of the hauling of merchandise is done[29]

[30]by men, horses being rarely seen. In fact, in some of the cities thereare more oxen than horses, and many of them wear straw sandals toprotect their hoofs from the hard pavement. The lighter burdens arecarried in buckets or baskets, suspended from the ends of a pole andbalanced upon the shoulder.

In the country the demand for land is so great that most of the roadsare too narrow for any other vehicle than a hand cart. The highwaysconnecting the cities and principal towns, however, are of good width,are substantially constructed and well drained, and have massive stonebridges spanning the streams.

The clothing of the men presents an interesting variety. In officialcircles the European and American dress prevails. The silk hat andPrince Albert coat are in evidence at all day functions, and the dresssuit at evening parties. The western style of dress is also worn by manybusiness men, professional men and soldiers, and by students after theyreach the middle school, which corresponds to our high school. Thechange is taking place more rapidly among the young than among theadults and is more marked in the city than in the country. In one ofthe primary schools in Kyoto, I noticed that more than half of the childrengave evidence of the transition in dress. The change is also morenoticeable in the seaport cities than in the interior. At Kyoto, an inlandcity, the audience wore the native dress and all were seated onmats on the floor, while the next night at Osaka, a seaport, all saton chairs and nearly all wore the American dress. At the Osakameeting some forty Japanese young ladies from the Congregationalcollege sang "My Country 'Tis of Thee" in English.

The shopkeepers and clerks generally wear the native clothing,which consists of a divided skirt and a short kimono held in place bya sash. The laboring men wear loose knee breeches and a shirt inwarm weather; in cold weather they wear tight fitting breeches thatreach to the ankles and a loose coat. In the country the summerclothing is even more scanty. I saw a number of men working inthe field with nothing on but a cloth about the loins, and it wasearly in November, when I found a light overcoat comfortable.

A pipe in a wooden case and a tobacco pouch are often carried inthe belt or sash, for smoking is almost universal among both men andwomen.

Considerable latitude is allowed in footwear. The leather shoe haskept pace with the coat and vest, but where the native dress is worn,the sandal is almost always used. Among the well-to-do the foot isencased in a short sock made of white cotton cloth, which is kep[31]tscrupulously clean. The sock has a separate division for the greattoe, the sandal being held upon the foot by a cord which runs betweenthe first and second toes and, dividing, fastens on each sideof the sandal. These sandals are of wood and rest upon two blocksan inch or more high, the front one sloping toward the toe. Thesandal hangs loosely upon the foot and drags upon the pavementwith each step. The noise made by a crowd at a railroad stationrises above the roar of the train. In muddy weather a higher sandalis used which raises the feet three or four inches from the ground,and the wearers stalk about as if on stilts. The day laborers weara cheaper sandal made of woven rope or straw. The footwear above[32]described comes down from time immemorial, but there is cominginto use among the 'rikisha men a modern kind of footwear whichis a compromise between the new and the old. It is a dark cloth,low-topped gaiter with a rubber sole and no heel. These have theseparate pocket for the great toe. The sandals are left at the door.At public meetings in Japanese halls the same custom is followed,the sandals being checked at the door as hats and wraps are in ourcountry. On approaching a meeting place the speaker can formsome estimate of the size of the audience by the size of the piles ofsandals on the outside. After taking cold twice, I procured a pairof felt slippers and carried them with me, and the other members ofthe family did likewise.

The women still retain the primitive dress. About 1884 an attemptwas made by the ladies of the court to adopt the Europeandress and quite a number of women in official circles purchased gownsin London, Paris and the United States, in spite of the protests oftheir sisters abroad. (Mrs. Cleveland joined in a written remonstrancewhich was sent from the United States.) But the spell wasbroken in a very few months and the women outside of the courtcircles returned to the simpler and more becoming native garb. Itis not necessary to enter into details regarding the female toilet, asthe magazines have made the world familiar with the wide sleeved,loose fitting kimono with its convenient pockets. The children wearbright colors, but the adults adopt more quiet shades.

The shape of the garment never changes, but the color does. Thisseason grey has been the correct shade. Feminine pride shows itselfin the obi, a broad sash or belt tied in a very stiff and incomprehensiblebow at the back. The material used for the obi is often brightin color and of rich and expensive brocades. A wooden disc is oftenconcealed within the bow of the obi to keep it in shape and also tobrace the back. Two neck cloths are usually worn, folded inside thekimono to protect the bare throat. These harmonize with the obiin color and give a dainty finish to the costume. As the kimono isquite narrow in the skirt, the women take very short steps. Thisshort step, coupled with the dragging of the sandals, makes thewomen's gait quite unlike the free stride of the American woman.In the middle and higher schools the girls wear a pleated skirt overthe kimono. These are uniform for each school and wine color isthe shade now prevailing. The men and women of the same classwear practically the same kind of shoes.

Next to the obi, the hair receives the greatest attention and it is[33]certainly arranged with elaborate care. The process is so complicatedthat a hair dresser is employed once or twice a week and beetle'soil is used in many instances to make the hair smooth and glossy. Atnight the Japanese women place a very hard, round cushion underthe neck in order to keep the hair from becoming disarranged. Thestores now have on sale air pillows, which are more comfortable thanthe wooden ones formerly used. The vexing question of millineryis settled by dispensing with hats entirely. Among the poorer classesthe hat is seldom used by the men.

More interesting in appearance than either the men or women arethe children—and I may add that there is no evidence of race suicidein Japan. They are to be seen everywhere, and a good natured lotthey are. The babies are carried on the back of the mother or anolder child, and it is not unusual to see the baby fast asleep whilethe bearer goes about her work. Of the tens of thousands of babieswe have seen, scarcely a half dozen have been crying. The youngerchildren sometimes have the lower part of the head shaved, leavinga cap of long hair on the crown of the head. Occasionally a spot isshaved in the center of this cap. After seeing the children on thestreets, one can better appreciate the Japanese dolls, which look sostrange to American children.

Cleanliness is the passion of the Japanese. The daily bath is amatter of routine, and among the middle classes there are probablymore who go above this average than below. It is said that in thecity of Tokyo there are over eleven hundred public baths, and it isestimated that five hundred thousand baths are taken daily at theseplaces. The usual charge is one and a quarter cents (in our money)for adults and one cent for children. One enthusiastic admirer ofJapan declares that a Japanese boy, coming unexpectedly into thepossession of a few cents, will be more apt to spend it on a baththan on something to eat or drink. The private houses have bathswherever the owners can afford them. The bath tub is made likea barrel—sometimes of stone, but more often of wood—and is sunkbelow the level of the floor. The favorite temperature is one hundredand ten degrees, and in the winter time the bath tub often takes theplace of a stove. In fact, at the hot springs people have been knownto remain in the bath for days at a time. I do not vouch forthe statement, but Mr. Basil H. Chamberlain in his book entitled"Things Japanese," says that when he was at one of these hot springs"the caretaker of the establishment, a hale old man of eighty, usedto stay in the bath during the entire winter." Until recently the[34]men and women bathed promiscuously in the public baths; occasionally,but not always, a string separated the bathers. Now differentapartments must be provided.

The Japanese are a very polite people. They have often beenlikened to the French in this respect—the French done in bronze,so to speak. They bow very low, and in exchanging salutations andfarewells sometimes bow several times. When the parties are seatedon the floor, they rise to the knees and bow the head to the floor.Servants, when they bring food to those who are seated on the floor,drop upon their knees and, bowing, present the tray.

In speaking of the people I desire to emphasize one conclusion thathas been drawn from my observations here, viz., that I have neverseen a more quiet, orderly or self-restrained people. I have visitedall of the larger cities and several of the smaller ones, in all partsof the islands; have mingled in the crowds that assembled at Tokyoand at Yokohama at the time of the reception to Togo and duringthe naval review; have ridden through the streets in day time andat night; and have walked when the entire street was a mass ofhumanity. I have not seen one drunken native or witnessed a fightor altercation of any kind. This is the more remarkable when itis remembered that these have been gala days when the entire populationturned out to display its patriotism and to enjoy a vacation.

The Japanese house deserves a somewhat extended description. Itis built of wood, is one story in height, unpainted and has a thatchedor a tile roof. The thatched roof is cheaper, but far less durable.Some of the temples and palaces have a roof constructed like athatched roof in which the bark of the arbor vitæ is used in placeof grass or straw. These roofs are often a foot thick and are quiteimposing. In cities most buildings are roofed with tile of a patternwhich has been used for hundreds of years. Shingles are sometimesused on newer structures, but they are not nearly so large as ourshingles, and instead of being fastened with nails, are held in placeby wire. On the business streets the houses are generally two stories,the merchant living above the store. The public buildings are nowbeing constructed of brick and stone and modeled after the buildingsof America and Europe. But returning to the native architecture—thehouse is really little more than a frame, for the dividingwalls are sliding screens, and, except in cold weather, the outsidewalls are taken out during the day. The rooms open into each other,the hallway extending around the outside instead of going throughthe center. Frail sliding partitions covered with paper separate the[35]rooms from the hall, glass being almost unknown. The floor is coveredwith a heavy matting two inches thick, and as these mats areof uniform size, six feet by three, the rooms are made to fit the mats,twelve feet square being the common size. As the walls of the roomare not stationary, there is no place for the hanging of pictures,although the sliding walls are often richly decorated. Such picturesas the house contains are painted on silk or paper and are rolled upwhen not on exhibition. At one end of the room used for company,there is generally a raised platform upon which a pot of flowers orother ornament is placed, and above this there are one or two shelves,the upper one being inclosed in sliding doors. There are no bedsteads,the beds being made upon the floor and rolled up during theday. There are no tables or chairs. There is usually a diminutivedesk about a foot high upon which writing material is placed. Thewriting is done with a brush and the writing case or box containingthe brush, ink, etc., has furnished the lacquer industry with one ofthe most popular articles for ornamentation. The people sit uponcushions upon the floor and their meals are served upon trays.

Japanese food is so different from American food that it takes thevisitor some time to acquire a fondness for it, more time than thetourist usually has at his disposal. With the masses rice is the staplearticle of diet, and it is the most palatable native dish that the foreignerfinds here. The white rice raised in Japan is superior inquality to some of the rice raised in China, and the farmers areoften compelled to sell good rice and buy the poorer quality. Millet,which is even cheaper, is used as a substitute for rice.

As might be expected in a seagirt land, fish, lobster, crab, shrimp,etc., take the place of meat, the fish being often served raw. As amatter of fact, it is sometimes brought to the table alive and carvedin the presence of the guests. Sweet potatoes, pickled radishes, mushrooms,sea weed, barley and fruit give variety to the diet. The radishesare white and enormous in size. I saw some which were twofeet long and two and a half inches in diameter. Another varietyis conical in form and six or eight inches in diameter. I heard ofa kind of turnip which grows so large that two of them make a loadfor the small Japanese horses. The chicken is found quite generallythroughout the country, but is small like the fighting breeds or theLeghorns. Ducks, also, are plentiful. Milk is seldom used except incase of sickness, and butter is almost unknown among the masses.

But the subject of food led me away from the house. No descriptionwould be complete which did not mention the little gate through[36]which the tiny door yard is entered; the low doorway upon whichthe foreigner constantly bumps his head, and the little garden at therear of the house with its fish pond, its miniature mountains, itsclimbing vines and fragrant flowers. The dwarf trees are cultivatedhere, and they are a delight to the eye; gnarled and knotted pinestwo feet high and thirty or forty years old are not uncommon. Littlemaple trees are seen here fifty years old and looking all of their age,but only twelve inches in height. We saw a collection of these dwarftrees, several hundred in number, and one could almost imaginehimself transported to the home of the brownies. Some of thesetrees bear fruit ludicrously large for the size of the tree. The housesare heated by charcoal fires in open urns or braziers, but an Americanwould not be satisfied with the amount of heat supplied. Thesebraziers are moved about the room as convenience requires and supplyheat for the inevitable tea.

But I have reached the limit of this article and must defer untilthe next description of the Japanese customs as we found them inthe homes which we were privileged to visit.

Every nation has its customs, its way of doing things, and a nation'scustoms and ways are likely to be peculiar in proportion as the nationis isolated. In Japan, therefore, one would expect to see many strangethings, and the expectation is more than realized. In some thingstheir customs are exactly the opposite of ours. In writing they placetheir characters in vertical lines and move from right to left, whileour letters are arranged on horizontal lines and read from left toright. Their books begin where ours end and end where ours begin.The Japanese carpenters pull the saw and plane toward them, whileours push them from them. The Japanese mounts his steed fromthe right, while the American mounts from the left; Japanese turnto the left, Americans to the right. Japanese write it "Smith JohnMr.," while we say "Mr. John Smith." At dinners in Japan wineis served hot and soup cold, and the yard is generally at the backof the house instead of the front.

The Japanese wear white for mourning and often bury their deadin a sitting posture. The death is sometimes announced as occurringat the house when it actually occurred elsewhere, and the date of thedeath is fixed to suit the convenience of the family. This is partlydue to the fact that the Japanese like to have the death appear asoccurring at home. Sometimes funeral services are held over a partof the body. An American lady whose Japanese maid died whileattending her mistress in the United States, reports an incident worthrelating. The lady cabled her husband asking instructions in regardto the disposition of the body. He conferred with the family of thedeceased and cabled back directing the wife to bring a lock of the hairand the false teeth of the departed. The instructions were followedand upon the delivery of these precious relics, they were interredwith the usual ceremonies.

The handshake is uncommon even among Japanese politicians,except in their intercourse with foreigners. When Baron Komura[38]returned from the peace conference in which he played so importanta part, I was anxious to witness his landing, partly out of respect tothe man and partly out of curiosity to see whether the threatenedmanifestations of disapproval would be made by the populace, it havingbeen rumored that thousands of death lanterns were being preparedfor a hostile parade. (It is needless to say that the threats didnot materialize and that no expressions of disapproval were heardafter his arrival.) I found it impossible to learn either the hour orthe landing place, and, despairing of being present, started to visita furniture factory to inspect some wood carving. Consul-GeneralJones of Dalney (near Port Arthur), then visiting in Yokohama,was my escort and, as good fortune would have it, we passed near theDetached Palace. Dr. Jones, hearing that the landing might be madethere, obtained permission for us to await the peace commissioner'scoming. We found Marquis Ito there and a half dozen other officials.As Baron Komura did not arrive for half an hour, it gave me thebest opportunity that I could have had to become acquainted with theMarquis, who is the most influential man in Japan at present. He[39]is President of the Privy Council of Elder Statesmen and is creditedwith being the most potent factor in the shaping of Japan's demandsat Portsmouth.

When Baron Komura stepped from the launch upon the soil ofhis native land, he was met by Marquis Ito, and each greeted theother with a low bow. The baron then saluted the other officials inthe same manner and, turning, bowed to a group of Japanese ladiesrepresenting the Woman's Patriotic Association. Dr. Jones and I stoodsome feet in the rear of the officials and were greeted by the baronafter he had saluted his own countrymen. He extended his hand tous. The incident is mentioned as illustrating the difference in themanner of greeting. For who would be more apt to clasp hands,if that were customary, than these two distinguished statesmen whosepersonalities are indissolubly linked together in the conclusion of aworld renowned treaty?

A brief account of the reception of Admiral Togo may be interestingto those who read this article. While at Tokyo I visited thecity hall, at the invitation of the mayor and city council. Whilethere Mayor Ozaki informed me that he, in company with the mayorsof the other cities, would tender Admiral Togo a reception on thefollowing Tuesday, and invited me to be present. Of course I accepted,because it afforded a rare opportunity to observe Japanese customsas well as to see a large concourse of people. As I witnessedthe naval review in Yokohama the day before and the illuminationat night, I did not reach Tokyo until the morning of the reception,and this led me into considerable embarrassment. On the train Imet a Japanese gentleman who could speak English. He was kindenough to find me a 'rikisha man and a pusher and to instruct themto take me at once to Uyeno Park. He then left me and the 'rikishamen followed his instructions to the letter. They had not proceededfar when I discovered that Admiral Togo had arrived on the sametrain and that a long procession had formed to conduct him to thepark. Before I knew it, I was whisked past an escort of distinguishedcitizens who, clad in Prince Alberts and silk hats, followed the carriages,and then I found my 'rikisha drawn into an open spacebetween two carriages. Grabbing the 'rikisha man in front of me, Itold him by word and gesture to get out of the line of the procession.He could not understand English, and evidently thinking that Iwanted to get nearer the front, he ran past a few carriages and thendropped into another opening. Again I got him out of the line,employing more emphasis than before, only to be carried still nearer[40]the front. After repeated changes of position, all the time employingsuch sign language as I could command and attempting to convey bydifferent tones of voice suggestions that I could not translate intolanguage, I at last reached the head of the procession. And the'rikisha men, as if satisfied with the success of their efforts, pausedto await the starting of the line. I tried to inform them that I wasnot a part of the procession; that I wanted to get on another street;that they should take me to the park by some other route and do soat once. They at last comprehended sufficiently to leave the carriagesand take up a rapid gait, but get off of the street they would not. Forthree miles they drew me between two rows of expectant people, whoseeyes peered down the street to catch a glimpse of the great admiral,who, as the commander of the Japanese navy, has won such signalvictories over the Russians. I saw a million people; they represented[41]every class, age and condition. I saw more people than I ever sawbefore in a single day. Old men and old women, feeble, but strengthenedby their enthusiasm; middle aged men and women whose sonshad shared in the dangers and in the triumphs of the navy; studentsfrom the boys' schools and students from the girls' schools with flagsand banners, little children dressed in all the colors of the rainbow—allwere there. And I could imagine that each one of them oldenough to think, was wondering why a foreigner was intruding upona street which the police had cleared for a triumphal procession. Ifsome one had angrily caught my 'rikisha men and thrust themthrough the crowd to a side street I should not have complained—Iwould even have felt relieved, but no one molested them or me andI reached the park some minutes ahead of the admiral. How gladI was to alight, and how willingly I rewarded the smiles of the 'rikishamen with a bonus—for had they not done their duty as they understoodit? And had they not also given me, in spite of my protests,such a view of the people of Tokyo as I could have obtained in noother way?

At the park I luckily fell in with some of the councilmen whomI had met before and they took me in hand. I saw the processionarrive, heard the banzais (the Japanese cheers) as they rolled alongthe street, keeping pace with Togo's carriage, and I witnessed theearnest, yet always orderly, rejoicing of the crowd that had congregatedat the end of the route. When the procession passed byus into the park the members of the city council fell in behind thecarriages, and I with them. When we reached the stand, a seat wastendered me on the front row from which the extraordinary ceremoniesattending the reception could be witnessed. Mayor Ozaki, thepresiding officer, escorted Admiral Togo to a raised platform, andthere the two took seats on little camp stools some ten feet apart, facingeach other, with their sides to the audience and to those on the stand.After a moment's delay, a priest, clad in his official robes, approachedwith cake and a teacup on a tray and, kneeling, placed them beforethe admiral. Tea was then brought in a long handled pot and pouredinto the cup. After the distinguished guest had partaken of theserefreshments, the mayor arose and read an address of welcome. Hehas the reputation of being one of the best orators in the empire, andhis part was doubly interesting to me. As he confined himself to hismanuscript, I could not judge of his delivery, but his voice was pleasingand his manner natural. The address recited the exploits of AdmiralTogo and gave expression to the gratitude of the people. At[42]its conclusion the hero-admiral arose and modestly acknowledged thecompliment paid to him and to his officers. Admiral Togo is short,even for the Japanese, and has a scanty beard. Neither in stature norin countenance does he give evidence of the stern courage and indomitablewill which have raised him to the pinnacle of fame.

When he sat down the mayor proposed three times three banzais,and they were given with a will by the enormous crowd that stood inthe open place before the stand. While writing this article, I amin receipt of information that Mayor Ozaki has secured for me oneof the little camp stools above referred to and has had made for mea duplicate of the other. They will not only be interesting souvenirsof an historic occasion, and prized as such, but they will be interestingalso because they contrast so sharply with the large and richly upholsteredchairs used in America on similar occasions.

From this public meeting the admiral and his officers were conductedto a neighboring hall where an elaborate luncheon was served.With the councilmen I went to this hall and was presented to theadmiral and his associates, one of whom had been a student atAnnapolis.

By the courtesy of Hon. Lloyd Griscom, the American minister, Ihad an audience with the emperor, these audiences being arrangedthrough the minister representing the country from which the callercomes. Our minister, to whom I am indebted for much assistanceand many kindnesses during my stay at the capital, accompanied meto the palace and instructed me, as they say in the fraternities, "in thesecret work of the order." Except where the caller wears a uniform,he is expected to appear in evening dress, although the hour fixed isin the day time. At the outer door stand men in livery, one of whomconducts the callers through long halls, beautifully decorated on ceilingsand walls, to a spacious reception room where a halt is madeuntil the summons comes from the emperor's room. The emperorstands in the middle of the receiving room with an interpreter at hisside. The caller on reaching the threshold bows; he then advanceshalf way to the emperor, pauses and bows again; he then proceedsand bows a third time as he takes the extended hand of the sovereign.

The conversation is brief and formal, consisting of answers to thequestions asked by his majesty. The emperor is fifty-three years old,about five feet six inches in height, well built and wears a beard,although, as is the case with most Japanese, the growth is not heavy.On retiring the caller repeats the three bows.

We were shown through the palace, and having seen the old palace[43]

[44]at Kyoto, which was the capital until the date of the restoration(1868), I was struck with the difference. The former was severelyplain; the latter represents the best that Japanese art can produce.

No discussion of Japanese customs would be complete without mentionof the tea ceremonial. One meets tea on his arrival; it is hisconstant companion during his stay and it is mingled with the farewellsthat speed him on his departure. Whenever he enters a househe is offered tea and cake and they are never refused. This customprevails in the larger stores and is scrupulously observed at public[45]buildings and colleges. The tea is served in dainty cups and takenwithout sugar or cream. The tea drinking habit is universal here,the kettle of hot water sitting on the coals in the brazier most of thetime. At each railroad station the boys sing out, "Cha! Cha!" (theJapanese word for tea) and for less than two cents in our money theywill furnish the traveler with an earthen pot of hot tea, with pot andcup thrown in.

The use of tea at social gatherings dates back at least six hundredyears, when a tea ceremonial was instituted by a Buddhist priest to[46]soften the manners of the warriors. It partook of a religious characterat first, but soon became a social form, and different schools oftea drinkers vied with each other in suggesting rules and methodsof procedure. About three hundred years ago Hideyoshi, one of thegreatest of the military rulers of Japan, gave what is described asthe largest tea party on record; the invitations being in the form ofan imperial edict. All lovers of tea were summoned to assemble ata given date in a pine grove near Kyoto, and they seem to have doneso. The tea party lasted ten days and the emperor drank at everybooth.

According to Chamberlain, tea drinking had reached the luxuriousstage before the middle of the fourteenth century. The lords tookpart in the daily gatherings, reclining on tiger skins, the walls ofthe guest chamber being richly ornamented. One of the populargames of that day was the offering of a number of varieties of tea,the guests being required to guess where each variety was produced,the best guess winning a handsome prize. The tea ceremony answeredat least one useful purpose—it furnished an innocent way of killingtime, and the lords of that day seem to have had an abundance oftime on their hands. The daughters of the upper classes were trainedto perform the ceremony and displayed much skill therein. Even tothis day it is regarded as one of the accomplishments, and youngladies perfect themselves in it, much as our daughters learn music andsinging. At Kagoshima, Governor Chikami, one of the most scholarlymen whom I have met here, had his daughter perform for my instructiona part of the ceremony, time not permitting more. Withcharming grace she prepared, poured and served this Japanese nectar,each motion being according to the rules of the most approved sect,for there are sects among tea drinkers.

The theatre is an ancient institution here, although until recentlythe actors were considered beneath even the mercantile class. Theirsocial standing has been somewhat improved since the advent of westernideas. The theatre building is very plain as compared with oursor even with the better class of homes here. They are always on theground floor and have a circular, revolving stage within the largerstage which makes it possible to change the scenes instantly.

The plays are divided into two kinds—historical ones reproducingold Japan, and modern plays. The performance often lasts throughthe entire day and evening, some of the audience bringing their teakettles and food. Lunches, fruit, cigarettes and tea are also on salein the theatre. The people sit on the floor as they do in their homes[47]and at public meetings. One of the side aisles is raised to the levelof the stage and the actors use it for entrance and exit.

In this connection a word should be said in regard to the Geishagirls who have furnished such ample material for the artist and thedecorator. They are selected for their beauty and trained in what iscalled a dance, although it differs so much from the American danceas scarcely to be describable by that term. It is rather a series ofgraceful poses in which gay costumes, dainty fans, flags, scarfs andsometimes parasols, play a part. The faces of the dancers are expressionlessand there is no exposure of the limbs. The Geisha girlsare often called in to entertain guests at a private dinner, the performancebeing before, not after, the meal.

Our first introduction to this national amusement was at the MapleClub dinner given at Tokyo by a society composed of Japanese menwho had studied in the United States. The name of the society is aJapanese phrase which means the "Friends of America." The MapleClub is the most famous restaurant in Japan, and the Geisha girlsemployed there stand at the head of their profession. During thedancing there is music on stringed instruments, which resembles thebanjo in tone, and sometimes singing. At the Maple Club the Geishagirls displayed American and Japanese flags. We saw the dancingagain at an elaborate dinner given by Mr. Fukuzawa, editor of theJiji Shimpo. Here also the flags of both nations were used.

In what words can I adequately describe the hospitality of theJapanese? I have read, and even heard, that among the more ignorantclasses there is a decided anti-foreign feeling, and it is not unnaturalthat those who refuse to reconcile themselves to Japan's new attitudeshould blame the foreigner for the change, but we did not encounterthis sentiment anywhere. Never in our own country have we beenthe recipients of more constant kindness or more considerate attention.From Marquis Ito down through all the ranks of official life we foundeveryone friendly to America, and to us as representatives of America.At the dinner given by Minister Griscom there were present, besidesMarquis Ito, the leader of the liberal party, Count Okuma, the leaderof the progressive party (the opposition party), and a number ofother prominent Japanese politicians.

At the dinner given by Consul General Miller at Yokohama, GovernorSufu and Mayor Ichihara were present. The state and cityofficials wherever we have been have done everything possible to makeour stay pleasant. The college and school authorities have openedtheir institutions to us and many without official position have in unmistakableways shown themselves friendly. We will carry away[48]with us a number of handsome presents bestowed by municipalities,colleges, societies and individuals.

We were entertained by Count Okuma soon after our arrival andmet there, among others, Mr. Kato of the state department, andPresident Hatoyama of the Waseda University, and their wives. Thecount's house is half European and half Japanese, and his gardenis celebrated for its beauty. At Viscount Kana's we saw a delightfulbit of home life. He is one of the few daimios, or feudal lords, whohas become conspicuous in the politics of Japan, and we soon discoveredthe secret of his success. He has devoted himself to the interestsof agriculture and spent his time in an earnest and intelligenteffort to improve the condition of the rural population. He is knownas "The Farmer's Friend." His house is at the top of a beautifullyterraced hill, which was once a part of his feudal estate. He andhis wife and six children met us at the bottom of the hill on ourarrival and escorted us to the bottom on our departure. The childrenassisted in serving the dinner and afterward sang for us the Americannational air as well as their own national hymn. The hospitalitywas so genuine and so heartily entered into by all the family thatwe could hardly realize that we were in a foreign land and entertainedby hosts to whom we had to speak through an interpreter.

In the country, fifteen miles from Kagoshima, I was a guest atthe home of Mr. Yamashita, the father of the young man, who, whena student in America, made his home with us for more than five years.Mr. Yamashita was of the samurai class and since the abolition offeudalism has been engaged in farming. He had invited his relativesand also the postmaster and the principal of the district schoolto the noon meal. He could not have been more thoughtful of mycomfort or more kindly in his manner. The little country schoolwhich stood near by turned out to bid us welcome. The childrenwere massed at a bridge over which large flags of the two nationsfloated from bamboo poles. Each child also held a flag, theJapanese and American flags alternating. As young Yamashita andI rode between the lines they waved their flags and shouted "Banzai."And so it was at other schools. Older people may be diplomatic andfeign good will, but children speak from their hearts. There is nomistaking their meaning, and in my memory the echo of the voicesof the children, mingling with the assurances of the men and women,convinces me that Japan entertains nothing but good will toward ournation. Steam has narrowed the Pacific and made us neighbors; letJustice keep us friends.