Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- The Nine Planets - Asteroid Facts

- Openstax - Astronomy 2e - Asteroids

- Lunar and Planetary Institute - Asteroids: New Challenges, New Targets

- Frontiers - Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences - Predicting Asteroid Types: Importance of Individual and Combined Features

- University of Central Florida Pressbooks - Asteroids

- NASA - Asteroids

- CUNY Pressbooks Network - Introduction to Planetary Geology - Asteroids

- LiveScience - What are asteroids?

- Space.com - Asteroids: Fun facts and information about these space rocks

- K12 LibreTexts - Asteroids

asteroid

- What is an asteroid?

- Where are most asteroids found in our solar system?

- How big are asteroids compared to planets?

- What are asteroids made of?

- How do scientists study asteroids?

- Why are asteroids important for understanding the history of the solar system?

asteroid, any of a host ofsmall bodies, about 1,000 km (600 miles) or less in diameter, that orbit theSun primarily between the orbits ofMars andJupiter in a nearly flat ring called the asteroid belt. It is because of their small size and large numbers relative to the major planets that asteroids are also called minor planets. The twodesignations have been used interchangeably, though the termasteroid is more widely recognized by the general public. Among scientists, those who study individual objects with dynamically interesting orbits or groups of objects with similar orbital characteristics generally use the termminor planet, whereas those who study the physical properties of such objects usually refer to them asasteroids. The distinction between asteroids andmeteoroids having the same origin is culturally imposed and is basically one of size. Asteroids that are approximately house-sized (a few tens of metres across) and smaller are often called meteoroids, though the choice may depend somewhat on context—for example, whether they are considered objects orbiting in space (asteroids) or objects having the potential to collide with aplanet, naturalsatellite, or other comparatively large body or with a spacecraft (meteoroids).

Major milestones in asteroid research

Early discoveries

The first asteroid was discovered on January 1, 1801, by the astronomerGiuseppe Piazzi atPalermo, Italy. At first Piazzi thought he had discovered acomet; however, after the orbital elements of the object had been computed, it became clear that the object moved in a planetlike orbit between the orbits ofMars and Jupiter. Because of illness, Piazzi was able to observe the object only until February 11. Although the discovery was reported in the press, Piazzi only shared details of his observations with a few astronomers and did not publish a complete set of his observations until months later. With the mathematics then available, the short arc of observations did not allow computation of an orbit of sufficient accuracy to predict where the object would reappear when it moved back into the night sky, so some astronomers did not believe in the discovery at all.

There matters might have stood had it not been for the fact that that object was located at the heliocentric distance predicted byBode’s law of planetary distances, proposed in 1766 by the German astronomerJohann D. Titius and popularized by his compatriotJohann E. Bode, who used the scheme to advance thenotion of a “missing” planet between Mars and Jupiter. The discovery of the planetUranus in 1781 by the British astronomerWilliam Herschel at a distance that closely fit the distance predicted by Bode’s law was taken as strong evidence of its correctness. Some astronomers were so convinced that they agreed during an astronomical conference in 1800 to undertake a systematic search. Ironically, Piazzi was not a party to that attempt to locate the missing planet. Nonetheless, Bode and others, on the basis of the preliminary orbit, believed that Piazzi had found and then lost it. That led German mathematicianCarl Friedrich Gauss to develop in 1801 a method for computing the orbit of minor planets from only a few observations, a technique that has not been significantly improved since. The orbital elements computed by Gauss showed that, indeed, the object moved in a planetlike orbit between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. Using Gauss’s predictions, German Hungarian astronomerFranz von Zach (ironically, the one who had proposed making a systematic search for the “missing” planet) rediscovered Piazzi’s object on December 7, 1801. (It was also rediscovered independently by German astronomerWilhelm Olbers on January 2, 1802.) Piazzi named that objectCeres after the ancient Roman grain goddess and patron goddess ofSicily, thereby initiating a tradition that continues to the present day: asteroids are named by their discoverers (in contrast to comets, which are named for their discoverers).

The discovery of three more faint objects in similar orbits over the next six years—Pallas,Juno, andVesta—complicated that elegant solution to the missing-planet problem and gave rise to the surprisingly long-lived though no longer accepted idea that the asteroids were remnants of a planet that had exploded.

Following that flurry of activity, the search for the planet appears to have been abandoned until 1830, whenKarl L. Hencke renewed it. In 1845 he discovered a fifth asteroid, which he namedAstraea.

The nameasteroid (Greek for “starlike”) had been suggested to Herschel by classicist Charles Burney, Jr., via his father, music historianCharles Burney, Sr., who was a close friend of Herschel’s. Herschel proposed the term in 1802 at a meeting of theRoyal Society. However, it was not accepted until the mid-19th century, when it became clear that Ceres and the other asteroids were not planets.

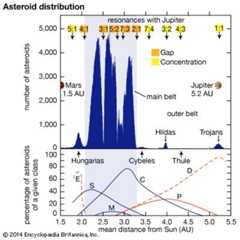

There were 88 known asteroids by 1866, when the next major discovery was made:Daniel Kirkwood, an American astronomer, noted that there weregaps (now known asKirkwood gaps) in the distribution of asteroid distances from the Sun (see belowDistribution and Kirkwood gaps). The introduction ofphotography to the search for new asteroids in 1891, by which time 322 asteroids had been identified,accelerated the discovery rate. The asteroid designated(323) Brucia, detected in 1891, was the first to be discovered by means of photography. By the end of the 19th century, 464 had been found, and that number grew to 108,066 by the end of the 20th century and more than 1,000,000 in the third decade of the 21st century. The explosive growth was a spin-off of a survey designed to find 90 percent of asteroids with diameters greater than one kilometre that can crossEarth’s orbit and thus have the potential to collide with the planet (see belowNear-Earth asteroids).

Later advances

In 1918 the Japanese astronomerHirayama Kiyotsugu recognizedclustering in three of the orbital elements (semimajor axis, eccentricity, and inclination) of various asteroids. He speculated that objects sharing those elements had been formed by explosions of larger parent asteroids, and he called such groups of asteroids “families.”

In the mid-20th century, astronomers began to consider the idea that, during the formation of thesolar system, Jupiter was responsible for interrupting the accretion of a planet from a swarm of planetesimals located about 2.8astronomical units (AU) from the Sun; for elaboration of this idea,see belowOrigin and evolution of the asteroids. (One astronomical unit is the average distance from Earth to the Sun—about 150 million km [93 million miles].) About the same time, calculations of the lifetimes of asteroids whose orbits passed close to those of the major planets showed that most such asteroids were destined either to collide with a planet or to be ejected from the solar system on timescales of a few hundred thousand to a few million years. Since the age of the solar system is approximately 4.6 billion years, this meant that the asteroids seen today in such orbits must have entered them recently and implied that there was a source for those asteroids. At first that source was thought to be comets that had been captured by the planets and that had lost their volatile material through repeated passages inside the orbit of Mars. It is now known that most such objects come from regions in the main asteroid belt near Kirkwood gaps and other orbitalresonances.

- Also called:

- minor planet

- Or:

- planetoid

During much of the 19th century, most discoveries concerning asteroids were based on studies of their orbits. The vast majority of knowledge about the physical characteristics of asteroids—for example, their size, shape, rotation period,composition, mass, and density—was learned beginning in the 20th century, in particular since the 1970s. As a result of such studies, those objects went from being merely “minor” planets to becoming small worlds in their own right. The discussion below follows that progression in knowledge, focusing first on asteroids as orbiting bodies and then on their physical nature.