I wrote this class for testing:

class PassByReference: def __init__(self): self.variable = 'Original' self.change(self.variable) print(self.variable) def change(self, var): var = 'Changed'When I tried creating an instance, the output wasOriginal. So it seems like parameters in Python are passed by value. Is that correct? How can I modify the code to get the effect of pass-by-reference, so that the output isChanged?

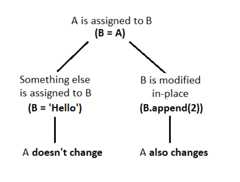

Sometimes people are surprised that code likex = 1, wherex is a parameter name, doesn't impact on the caller's argument, but code likex[0] = 1 does. This happens becauseitem assignment andslice assignment are ways tomutate an existing object, rather than reassign a variable, despite the= syntax. SeeWhy can a function modify some arguments as perceived by the caller, but not others? for details.

See alsoWhat's the difference between passing by reference vs. passing by value? for important, language-agnostic terminology discussion.

- 33For a short explanation/clarification see the first answer tothis stackoverflow question. As strings are immutable, they won't be changed and a new variable will be created, thus the "outer" variable still has the same value.PhilS– PhilS2009-06-12 10:35:53 +00:00CommentedJun 12, 2009 at 10:35

- 12The code in BlairConrad's answer is good, but the explanation provided by DavidCournapeau and DarenThomas is correct.Ethan Furman– Ethan Furman2012-01-07 06:47:10 +00:00CommentedJan 7, 2012 at 6:47

- 80Before reading the selected answer, please consider reading this short textOther languages have "variables", Python has "names". Think about "names" and "objects" instead of "variables" and "references" and you should avoid a lot of similar problems.lqc– lqc2012-11-15 00:39:20 +00:00CommentedNov 15, 2012 at 0:39

- 4Working link:Other languages have "variables", Python has "names"Abraham Sangha– Abraham Sangha2020-04-22 23:30:31 +00:00CommentedApr 22, 2020 at 23:30

- 14New official how of Iqc's link:david.goodger.org/projects/pycon/2007/idiomatic/…Ray Hulha– Ray Hulha2020-06-09 19:56:56 +00:00CommentedJun 9, 2020 at 19:56

44 Answers44

Arguments arepassed by assignment. The rationale behind this is twofold:

- the parameter passed in is actually areference to an object (but the reference is passed by value)

- some data types are mutable, but others aren't

So:

If you pass amutable object into a method, the method gets a reference to that same object and you can mutate it to your heart's delight, but if you rebind the reference in the method, the outer scope will know nothing about it, and after you're done, the outer reference will still point at the original object.

If you pass animmutable object to a method, you still can't rebind the outer reference, and you can't even mutate the object.

To make it even more clear, let's have some examples.

List - a mutable type

Let's try to modify the list that was passed to a method:

def try_to_change_list_contents(the_list): print('got', the_list) the_list.append('four') print('changed to', the_list)outer_list = ['one', 'two', 'three']print('before, outer_list =', outer_list)try_to_change_list_contents(outer_list)print('after, outer_list =', outer_list)Output:

before, outer_list = ['one', 'two', 'three']got ['one', 'two', 'three']changed to ['one', 'two', 'three', 'four']after, outer_list = ['one', 'two', 'three', 'four']Since the parameter passed in is a reference toouter_list, not a copy of it, we can use the mutating list methods to change it and have the changes reflected in the outer scope.

Now let's see what happens when we try to change the reference that was passed in as a parameter:

def try_to_change_list_reference(the_list): print('got', the_list) the_list = ['and', 'we', 'can', 'not', 'lie'] print('set to', the_list)outer_list = ['we', 'like', 'proper', 'English']print('before, outer_list =', outer_list)try_to_change_list_reference(outer_list)print('after, outer_list =', outer_list)Output:

before, outer_list = ['we', 'like', 'proper', 'English']got ['we', 'like', 'proper', 'English']set to ['and', 'we', 'can', 'not', 'lie']after, outer_list = ['we', 'like', 'proper', 'English']Since thethe_list parameter was passed by value, assigning a new list to it had no effect that the code outside the method could see. Thethe_list was a copy of theouter_list reference, and we hadthe_list point to a new list, but there was no way to change whereouter_list pointed.

String - an immutable type

It's immutable, so there's nothing we can do to change the contents of the string

Now, let's try to change the reference

def try_to_change_string_reference(the_string): print('got', the_string) the_string = 'In a kingdom by the sea' print('set to', the_string)outer_string = 'It was many and many a year ago'print('before, outer_string =', outer_string)try_to_change_string_reference(outer_string)print('after, outer_string =', outer_string)Output:

before, outer_string = It was many and many a year agogot It was many and many a year agoset to In a kingdom by the seaafter, outer_string = It was many and many a year agoAgain, since thethe_string parameter was passed by value, assigning a new string to it had no effect that the code outside the method could see. Thethe_string was a copy of theouter_string reference, and we hadthe_string point to a new string, but there was no way to change whereouter_string pointed.

I hope this clears things up a little.

EDIT: It's been noted that this doesn't answer the question that @David originally asked, "Is there something I can do to pass the variable by actual reference?". Let's work on that.

How do we get around this?

As @Andrea's answer shows, you could return the new value. This doesn't change the way things are passed in, but does let you get the information you want back out:

def return_a_whole_new_string(the_string): new_string = something_to_do_with_the_old_string(the_string) return new_string# then you could call it likemy_string = return_a_whole_new_string(my_string)If you really wanted to avoid using a return value, you could create a class to hold your value and pass it into the function or use an existing class, like a list:

def use_a_wrapper_to_simulate_pass_by_reference(stuff_to_change): new_string = something_to_do_with_the_old_string(stuff_to_change[0]) stuff_to_change[0] = new_string# then you could call it likewrapper = [my_string]use_a_wrapper_to_simulate_pass_by_reference(wrapper)do_something_with(wrapper[0])Although this seems a little cumbersome.

19 Comments

def foo(&var): var = 2 thenx = 0; y = 1; foo(x); foo(y) thenprint(x, y) would print2 2The problem comes from a misunderstanding of what variables are in Python. If you're used to most traditional languages, you have a mental model of what happens in the following sequence:

a = 1a = 2You believe thata is a memory location that stores the value1, then is updated to store the value2. That's not how things work in Python. Rather,a starts as a reference to an object with the value1, then gets reassigned as a reference to an object with the value2. Those two objects may continue to coexist even thougha doesn't refer to the first one anymore; in fact they may be shared by any number of other references within the program.

When you call a function with a parameter, a new reference is created that refers to the object passed in. This is separate from the reference that was used in the function call, so there's no way to update that reference and make it refer to a new object. In your example:

def __init__(self): self.variable = 'Original' self.Change(self.variable)def Change(self, var): var = 'Changed'self.variable is a reference to the string object'Original'. When you callChange you create a second referencevar to the object. Inside the function you reassign the referencevar to a different string object'Changed', but the referenceself.variable is separate and does not change.

The only way around this is to pass a mutable object. Because both references refer to the same object, any changes to the object are reflected in both places.

def __init__(self): self.variable = ['Original'] self.Change(self.variable)def Change(self, var): var[0] = 'Changed'13 Comments

id gives the identity of the object referenced, not the reference itself.I found the other answers rather long and complicated, so I created this simple diagram to explain the way Python treats variables and parameters.

7 Comments

A=B orB=A.mutable vsimmutable which makes the right leg moot since there will be noappend available. (still got an upvote for the visual rep though) :)append method then it must be mutable.It is neither pass-by-value or pass-by-reference - it is call-by-object. See this, by Fredrik Lundh:

Here is a significant quote:

"...variables [names] arenot objects; they cannot be denoted by other variables or referred to by objects."

In your example, when theChange method is called--anamespace is created for it; andvar becomes a name, within that namespace, for the string object'Original'. That object then has a name in two namespaces. Next,var = 'Changed' bindsvar to a new string object, and thus the method's namespace forgets about'Original'. Finally, that namespace is forgotten, and the string'Changed' along with it.

10 Comments

swap function that can swap two references, like this:a = [42] ; b = 'Hello'; swap(a, b) # Now a is 'Hello', b is [42]Think of stuff being passedby assignment instead of by reference/by value. That way, it is always clear, what is happening as long as you understand what happens during the normal assignment.

So, when passing a list to a function/method, the list is assigned to the parameter name. Appending to the list will result in the list being modified. Reassigning the listinside the function will not change the original list, since:

a = [1, 2, 3]b = ab.append(4)b = ['a', 'b']print a, b # prints [1, 2, 3, 4] ['a', 'b']Since immutable types cannot be modified, theyseem like being passed by value - passing an int into a function means assigning the int to the function's parameter. You can only ever reassign that, but it won't change the original variables value.

1 Comment

There are no variables in Python

The key to understanding parameter passing is to stop thinking about "variables". There are names and objects in Python and together theyappear like variables, but it is useful to always distinguish the three.

- Python has names and objects.

- Assignment binds a name to an object.

- Passing an argument into a function also binds a name (the parameter name of the function) to an object.

That is all there is to it. Mutability is irrelevant to this question.

Example:

a = 1This binds the namea to an object of type integer that holds the value 1.

b = xThis binds the nameb to the same object that the namex is currently bound to.Afterward, the nameb has nothing to do with the namex anymore.

See sections3.1 and4.2 in the Python 3 language reference.

How to read the example in the question

In the code shown in the question, the statementself.Change(self.variable) binds the namevar (in the scope of functionChange) to the object that holds the value'Original' and the assignmentvar = 'Changed' (in the body of functionChange) assigns that same name again: to some other object (that happens to hold a string as well but could have been something else entirely).

How to pass by reference

So if the thing you want to change is a mutable object, there is no problem, as everything is effectively passed by reference.

If it is animmutable object (e.g. a bool, number, string), the way to go is to wrap it in a mutable object.

The quick-and-dirty solution for this is a one-element list (instead ofself.variable, pass[self.variable] and in the function modifyvar[0]).

The morepythonic approach would be to introduce a trivial, one-attribute class. The function receives an instance of the class and manipulates the attribute.

12 Comments

int declares a variable, butInteger does not. They both declare variables. TheInteger variable is an object, theint variable is a primitive. As an example, you demonstrated how your variables work by showinga = 1; b = a; a++ # doesn't modify b. That's exactly true in Python also (using+= 1 since there is no++ in Python)!Effbot (aka Fredrik Lundh) has described Python's variable passing style as call-by-object:https://web.archive.org/web/20201111195827/http://effbot.org/zone/call-by-object.htm

Objects are allocated on the heap and pointers to them can be passed around anywhere.

When you make an assignment such as

x = 1000, a dictionary entry is created that maps the string "x" in the current namespace to a pointer to the integer object containing one thousand.When you update "x" with

x = 2000, a new integer object is created and the dictionary is updated to point at the new object. The old one thousand object is unchanged (and may or may not be alive depending on whether anything else refers to the object).When you do a new assignment such as

y = x, a new dictionary entry "y" is created that points to the same object as the entry for "x".Objects like strings and integers areimmutable. This simply means that there are no methods that can change the object after it has been created. For example, once the integer object one-thousand is created, it will never change. Math is done by creating new integer objects.

Objects like lists aremutable. This means that the contents of the object can be changed by anything pointing to the object. For example,

x = []; y = x; x.append(10); print ywill print[10]. The empty list was created. Both "x" and "y" point to the same list. Theappend method mutates (updates) the list object (like adding a record to a database) and the result is visible to both "x" and "y" (just as a database update would be visible to every connection to that database).

Hope that clarifies the issue for you.

3 Comments

id() function returns the pointer's (object reference's) value, as pepr's answer suggests?locals() function needs to create adict on the fly.Technically,Python always uses pass by reference values. I am going to repeatmy other answer to support my statement.

Python always uses pass-by-reference values. There isn't any exception. Any variable assignment means copying the reference value. No exception. Any variable is the name bound to the reference value. Always.

You can think about a reference value as the address of the target object. The address is automatically dereferenced when used. This way, working with the reference value, it seems you work directly with the target object. But there always is a reference in between, one step more to jump to the target.

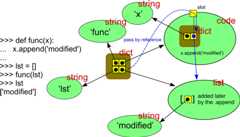

Here is the example that proves that Python uses passing by reference:

If the argument was passed by value, the outerlst could not be modified. The green are the target objects (the black is the value stored inside, the red is the object type), the yellow is the memory with the reference value inside -- drawn as the arrow. The blue solid arrow is the reference value that was passed to the function (via the dashed blue arrow path). The ugly dark yellow is the internal dictionary. (It actually could be drawn also as a green ellipse. The colour and the shape only says it is internal.)

You can use theid() built-in function to learn what the reference value is (that is, the address of the target object).

In compiled languages, a variable is a memory space that is able to capture the value of the type. In Python, a variable is a name (captured internally as a string) bound to the reference variable that holds the reference value to the target object. The name of the variable is the key in the internal dictionary, the value part of that dictionary item stores the reference value to the target.

Reference values are hidden in Python. There isn't any explicit user type for storing the reference value. However, you can use a list element (or element in any other suitable container type) as the reference variable, because all containers do store the elements also as references to the target objects. In other words, elements are actually not contained inside the container -- only the references to elements are.

20 Comments

A simple trick I normally use is to just wrap it in a list:

def Change(self, var): var[0] = 'Changed'variable = ['Original']self.Change(variable) print variable[0](Yeah I know this can be inconvenient, but sometimes it is simple enough to do this.)

2 Comments

Chnage usevar.my_str = 'Changed', wherevar is an instance ofWrapper with a fieldself.my_strYou got some really good answers here.

x = [ 2, 4, 4, 5, 5 ]print x # 2, 4, 4, 5, 5def go( li ) : li = [ 5, 6, 7, 8 ] # re-assigning what li POINTS TO, does not # change the value of the ORIGINAL variable xgo( x ) print x # 2, 4, 4, 5, 5 [ STILL! ]raw_input( 'press any key to continue' )1 Comment

In this case the variable titledvar in the methodChange is assigned a reference toself.variable, and you immediately assign a string tovar. It's no longer pointing toself.variable. The following code snippet shows what would happen if you modify the data structure pointed to byvar andself.variable, in this case a list:

>>> class PassByReference:... def __init__(self):... self.variable = ['Original']... self.change(self.variable)... print self.variable... ... def change(self, var):... var.append('Changed')... >>> q = PassByReference()['Original', 'Changed']>>>I'm sure someone else could clarify this further.

Comments

Python’s pass-by-assignment scheme isn’t quite the same as C++’s reference parameters option, but it turns out to be very similar to the argument-passing model of the C language (and others) in practice:

- Immutable arguments are effectively passed “by value.” Objects such as integers and strings are passed by object reference instead of by copying, but because you can’t change immutable objects in place anyhow, the effect is much like making a copy.

- Mutable arguments are effectively passed “by pointer.” Objects such as listsand dictionaries are also passed by object reference, which is similar to the way Cpasses arrays as pointers—mutable objects can be changed in place in the function,much like C arrays.

Comments

There are a lot of insights in answers here, but I think an additional point is not clearly mentioned here explicitly. Quoting from Python documentationWhat are the rules for local and global variables in Python?

In Python, variables that are only referenced inside a function are implicitly global. If a variable is assigned a new value anywhere within the function’s body, it’s assumed to be a local. If a variable is ever assigned a new value inside the function, the variable is implicitly local, and you need to explicitly declare it as ‘global’.Though a bit surprising at first, a moment’s consideration explains this. On one hand, requiring global for assigned variables provides a bar against unintended side-effects. On the other hand, if global was required for all global references, you’d be using global all the time. You’d have to declare as global every reference to a built-in function or to a component of an imported module. This clutter would defeat the usefulness of the global declaration for identifying side-effects.

Even when passing a mutable object to a function this still applies. And to me it clearly explains the reason for the difference in behavior between assigning to the object and operating on the object in the function.

def test(l): print "Received", l, id(l) l = [0, 0, 0] print "Changed to", l, id(l) # New local object created, breaking link to global ll = [1, 2, 3]print "Original", l, id(l)test(l)print "After", l, id(l)gives:

Original [1, 2, 3] 4454645632Received [1, 2, 3] 4454645632Changed to [0, 0, 0] 4474591928After [1, 2, 3] 4454645632The assignment to an global variable that is not declared global therefore creates a new local object and breaks the link to the original object.

Comments

As you can state you need to have a mutable object, but let me suggest you to check over the global variables as they can help you or even solve this kind of issue!

example:

>>> def x(y):... global z... z = y...>>> x<function x at 0x00000000020E1730>>>> yTraceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>NameError: name 'y' is not defined>>> zTraceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>NameError: name 'z' is not defined>>> x(2)>>> x<function x at 0x00000000020E1730>>>> yTraceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>NameError: name 'y' is not defined>>> z21 Comment

Here is the simple (I hope) explanation of the conceptpass by object used in Python.

Whenever you pass an object to the function, the object itself is passed (object in Python is actually what you'd call a value in other programming languages) not the reference to this object. In other words, when you call:

def change_me(list): list = [1, 2, 3]my_list = [0, 1]change_me(my_list)The actual object - [0, 1] (which would be called a value in other programming languages) is being passed. So in fact the functionchange_me will try to do something like:

[0, 1] = [1, 2, 3]which obviously will not change the object passed to the function. If the function looked like this:

def change_me(list): list.append(2)Then the call would result in:

[0, 1].append(2)which obviously will change the object.This answer explains it well.

5 Comments

list = [1, 2, 3] causes reusing thelist name for something else and forgeting the originally passed object. However, you can trylist[:] = [1, 2, 3] (by the waylist is wrong name for a variable. Thinking about[0, 1] = [1, 2, 3] is a complete nonsense. Anyway, what do you think meansthe object itself is passed? What is copied to the function in your opinion?[0, 1] = [1, 2, 3] is simply a bad example. There is nothing like that in Python.alist[2] counts as a name of a third element of alist. But I think I misunderstood what your problem was. :-)Aside from all the great explanations on how this stuff works in Python, I don't see a simple suggestion for the problem. As you seem to do create objects and instances, the Pythonic way of handling instance variables and changing them is the following:

class PassByReference: def __init__(self): self.variable = 'Original' self.Change() print self.variable def Change(self): self.variable = 'Changed'In instance methods, you normally refer toself to access instance attributes. It is normal to set instance attributes in__init__ and read or change them in instance methods. That is also why you passself as the first argument todef Change.

Another solution would be to create a static method like this:

class PassByReference: def __init__(self): self.variable = 'Original' self.variable = PassByReference.Change(self.variable) print self.variable @staticmethod def Change(var): var = 'Changed' return varComments

I used the following method to quickly convert some Fortran code to Python. True, it's not pass by reference as the original question was posed, but it is a simple workaround in some cases.

a = 0b = 0c = 0def myfunc(a, b, c): a = 1 b = 2 c = 3 return a, b, ca, b, c = myfunc(a, b, c)print a, b, c1 Comment

dict and then returns thedict. However, while cleaning up it may become apparent a rebuild of a part of the system is required. Therefore, the function must not only return the cleaneddict but also be able to signal the rebuild. I tried to pass abool by reference, but ofc that doesn't work. Figuring out how to solve this, I found your solution (basically returning a tuple) to work best while also not being a hack/workaround at all (IMHO).To simulate passing an object by reference, wrap it in a one-item list:

class PassByReference: def __init__(self, name): self.name = namedef changeRef(ref): ref[0] = PassByReference('Michael')obj = PassByReference('Peter')print(obj.name)p = [obj]changeRef(p)print(p[0].name)Assigning to an element of the list mutates the list rather than reassigning a name. Since the list itself has reference semantics, the change is reflected in the caller.

4 Comments

p is reference to a mutable list object which in turn stores the objectobj. The reference 'p', gets passed intochangeRef. InsidechangeRef, a new reference is created (the new reference is calledref) that points to the same list object thatp points to. But because lists are mutable, changes to the list are visible byboth references. In this case, you used theref reference to change the object at index 0 so that it subsequently stores thePassByReference('Michael') object. The change to the list object was done usingref but this change is visible top.p andref point to a list object that stores the single object,PassByReference('Michael'). So it follows thatp[0].name returnsMichael. Of course,ref has now gone out of scope and may be garbage collected but all the same.name, of the originalPassByReference object associated with the referenceobj, though. In fact,obj.name will returnPeter. The aforementioned comments assumes the definitionMark Ransom gave.PassByReference object with anotherPassByReference object in your list and referred to the latter of the two objects.Since it seems to be nowhere mentioned an approach to simulate references as known from e.g. C++ is to use an "update" function and pass that instead of the actual variable (or rather, "name"):

def need_to_modify(update): update(42) # set new value 42 # other codedef call_it(): value = 21 def update_value(new_value): nonlocal value value = new_value need_to_modify(update_value) print(value) # prints 42This is mostly useful for "out-only references" or in a situation with multiple threads / processes (by making the update function thread / multiprocessing safe).

Obviously the above does not allowreading the value, only updating it.

1 Comment

Given the way Python handles values and references to them, the only way you can reference an arbitrary instance attribute is by name:

class PassByReferenceIsh: def __init__(self): self.variable = 'Original' self.change('variable') print self.variable def change(self, var): self.__dict__[var] = 'Changed'In real code you would, of course, add error checking on the dict lookup.

Comments

Since your example happens to be object-oriented, you could make the following change to achieve a similar result:

class PassByReference: def __init__(self): self.variable = 'Original' self.change('variable') print(self.variable) def change(self, var): setattr(self, var, 'Changed')# o.variable will equal 'Changed'o = PassByReference()assert o.variable == 'Changed'3 Comments

__dict__ attribute; see the section on__slots__ for more details."docs.python.org/3/reference/datamodel.html#id5You can merely usean empty class as an instance to store reference objects because internally object attributes are stored in an instance dictionary. See the example.

class RefsObj(object): "A class which helps to create references to variables." pass...# an example of usagedef change_ref_var(ref_obj): ref_obj.val = 24ref_obj = RefsObj()ref_obj.val = 1print(ref_obj.val) # or print ref_obj.val for python2change_ref_var(ref_obj)print(ref_obj.val)Comments

Since dictionaries are passed by reference, you can use a dict variable to store any referenced values inside it.

# returns the result of adding numbers `a` and `b`def AddNumbers(a, b, ref): # using a dict for reference result = a + b ref['multi'] = a * b # reference the multi. ref['multi'] is number ref['msg'] = "The result: " + str(result) + " was nice!" return resultnumber1 = 5number2 = 10ref = {} # init a dict like that so it can save all the referenced values. this is because all dictionaries are passed by reference, while strings and numbers do not.sum = AddNumbers(number1, number2, ref)print("sum: ", sum) # the returned valueprint("multi: ", ref['multi']) # a referenced valueprint("msg: ", ref['msg']) # a referenced valueComments

While pass by reference is nothing that fits well into Python and should be rarely used, there are some workarounds that actually can work to get the object currently assigned to a local variable or even reassign a local variable from inside of a called function.

The basic idea is to have a function that can do that access and can be passed as object into other functions or stored in a class.

One way is to useglobal (for global variables) ornonlocal (for local variables in a function) in a wrapper function.

def change(wrapper): wrapper(7)x = 5def setter(val): global x x = valprint(x)The same idea works for reading anddeleting a variable.

For just reading, there is even a shorter way of just usinglambda: x which returns a callable that when called returns the current value of x. This is somewhat like "call by name" used in languages in the distant past.

Passing 3 wrappers to access a variable is a bit unwieldy so those can be wrapped into a class that has a proxy attribute:

class ByRef: def __init__(self, r, w, d): self._read = r self._write = w self._delete = d def set(self, val): self._write(val) def get(self): return self._read() def remove(self): self._delete() wrapped = property(get, set, remove)# Left as an exercise for the reader: define set, get, remove as local functions using global / nonlocalr = ByRef(get, set, remove)r.wrapped = 15Pythons "reflection" support makes it possible to get a object that is capable of reassigning a name/variable in a given scope without defining functions explicitly in that scope:

class ByRef: def __init__(self, locs, name): self._locs = locs self._name = name def set(self, val): self._locs[self._name] = val def get(self): return self._locs[self._name] def remove(self): del self._locs[self._name] wrapped = property(get, set, remove)def change(x): x.wrapped = 7def test_me(): x = 6 print(x) change(ByRef(locals(), "x")) print(x)Here theByRef class wraps a dictionary access. So attribute access towrapped is translated to a item access in the passed dictionary. By passing the result of the builtinlocals and the name of a local variable, this ends up accessing a local variable. The Python documentation as of 3.5 advises that changing the dictionary might not work, but it seems to work for me.

1 Comment

Pass-by-reference in Python is quite different from the concept of pass by reference in C++/Java.

Java and C#: primitive types (including string) pass by value (copy). A reference type is passed by reference (address copy), so all changes made in the parameter in the called function are visible to the caller.

C++: Both pass-by-reference or pass-by-value are allowed. If a parameter is passed by reference, you can either modify it or not depending upon whether the parameter was passed as const or not. However, const or not, the parameter maintains the reference to the object and reference cannot be assigned to point to a different object within the called function.

Python:Python is “pass-by-object-reference”, of which it is often said: “Object references are passed by value.” (read here). Both the caller and the function refer to the same object, but the parameter in the function is a new variable which is just holding a copy of the object in the caller. Like C++, a parameter can be either modified or not in function. This depends upon the type of object passed. For example, an immutable object type cannot be modified in the called function whereas a mutable object can be either updated or re-initialized.

A crucial difference between updating or reassigning/re-initializing the mutable variable is that updated value gets reflected back in the called function whereas the reinitialized value does not. The scope of any assignment of new object to a mutable variable is local to the function in the python. Examples provided by @blair-conrad are great to understand this.

Comments

There are already many great answers (or let's say opinions) about this and I've read them, but I want to mention a missing one. The one fromPython's documentation in the FAQ section. I don't know the date of publishing this page, but this should be our true reference:

Remember that arguments arepassed by assignment in Python. Sinceassignment just creates references to objects, there’s no aliasbetween an argument name in the caller and callee, and sonocall-by-reference per se.

If you have:

a = SOMETHINGdef fn(arg): passand you call it likefn(a), you're doing exactly what you do in assignment. So this happens:

arg = aAn additional reference toSOMETHING is created. Variables are just symbols/names/references. They don't "hold" anything.

Comments

I found other answers a little bit confusing and I had to struggle a while to grasp the concepts. So, I am trying to put the answer in my language. It may help you if other answers are confusing to you too. So, the answer is like this-

When you create a list-

my_list = []you are actually creating an object of the class list:

my_list = list()Here, my_list is just a name given to the memory address (e.g., 140707924412080) of the object created by the constructor of the 'list' class.

When you pass this list to a method defined as

def my_method1(local_list): local_list.append(1)another reference to the same memory address 140707924412080 is created. So, when you make any changes/mutate to the object by using append method, it is also reflected outside the my_method1. Because, both the outer list my_list and local_list are referencing the same memory address.

On the other hand, when you pass the same list to the following method,

def my_method2(local_list2): local_list2 = [1,2,3,4]the first half of the process remains the same. i.e., a new reference/name local_list2 is created which points to the same memory address 140707924412080. But when you create a new list [1,2,3,4], the constructor of the 'list' class is called again and a new object is created. This new object has a completely different memory address, e.g., 140707924412112. When you assign local_list2 to [1,2,3,4], now the local_list2 name refers to a new memory address which is 140707924412112. Since in this entire process you have not made any changes to the object placed at memory address 140707924412080, it remains unaffected.

In other words, it is in the spirit that 'other languages have variables, Python have names'. That means in other languages, variables are referenced to a fixed address in memory. That means, in C++, if you reassign a variable by

a = 1a = 2the memory address where the value '1' was stored is now holding the value '2' And hence, the value '1' is completely lost. Whereas in Python, since everything is an object, earlier 'a' referred to the memory address that stores the object of class 'int' which in turn stores the value '1'. But, after reassignment, it refers to a completely different memory address that stores the newly created object of class 'int' holding the value '2'.

Hope it helps.

Comments

I am new to Python, started yesterday (though I have been programming for 45 years).

I came here because I was writing a function where I wanted to have two so-called out-parameters. If it would have been only one out-parameter, I wouldn't get hung up right now on checking how reference/value works in Python. I would just have used the return value of the function instead. But since I neededtwo such out-parameters I felt I needed to sort it out.

In this post I am going to show how I solved my situation. Perhaps others coming here can find it valuable, even though it is not exactly an answer to the topic question. Experienced Python programmers of course already know about the solution I used, but it was new to me.

From the answers here I could quickly see that Python works a bit like JavaScript in this regard, and that you need to use workarounds if you want the reference functionality.

But then I found something neat in Python that I don't think I have seen in other languages before, namely that you can return more than one value from a function, in a simple comma-separated way, like this:

def somefunction(p): a = p + 1 b = p + 2 c = -p return a, b, cand that you can handle that on the calling side similarly, like this

x, y, z = somefunction(w)That was good enough for me and I was satisfied. There isn't any need to use some workaround.

In other languages you can of course also return many values, but then usually in the from of an object, and you need to adjust the calling side accordingly.

The Python way of doing it was nice and simple.

If you want to mimicby reference even more, you could do as follows:

def somefunction(a, b, c): a = a * 2 b = b + a c = a * b * c return a, b, cx = 3y = 5z = 10print(F"Before : {x}, {y}, {z}")x, y, z = somefunction(x, y, z)print(F"After : {x}, {y}, {z}")which gives this result

Before : 3, 5, 10After : 6, 11, 660

2 Comments

tuple, which is what the expressiona, b, c creates. You then useiterable unpacking to unpack that tuple into separate variables. Of course, in effect, you can think of this as "returning multiple values", but you aren't actually doing that, you are returning a container.Alternatively, you could usectypes which would look something like this:

import ctypesdef f(a): a.value = 2398 ## Resign the value in a functiona = ctypes.c_int(0)print("pre f", a)f(a)print("post f", a)As a is a c int and not a Python integer and apparently passed by reference. However, you have to be careful as strange things could happen, and it is therefore not advised.

Comments

Usedataclasses. Also, it allows you to apply type restrictions (aka "type hints").

from dataclasses import dataclass@dataclassclass Holder: obj: your_type # Need any type? Use "obj: object" then.def foo(ref: Holder): ref.obj = do_something()I agree with folks that in most cases you'd better consider not to use it.

And yet, when we're talking aboutcontexts, it's worth to know that way.

You can design an explicit context class though. When prototyping, I prefer dataclasses, just because it's easy to serialize them back and forth.

3 Comments

Explore related questions

See similar questions with these tags.