Sign Language Semantics

Sign languages (in the plural: there are many) arise naturally as soonas groups of deaf people have to communicate with each other. Signlanguages became institutionally established starting in the lateeighteenth century, when schools using sign languages were founded inFrance, and spread across different countries, gradually leading to agolden age of Deaf culture (we capitalizeDeaf when talkingabout members of a cultural group, and usedeaf for theaudiological status). This came to a partial halt in 1880, when theMilan Congress declared that oral education was superior to signlanguage education (Lane 1984)—a view that is amply refuted byresearch (Napoli et al. 2015). While sign languages continued to beused in Deaf education in some countries (e.g., the United States), itwas only in the 1970s that a Deaf Awakening gave renewed prominence tosign languages in the western world (see Lane 1984 for a broaderhistory).

Besides their essential role in Deaf culture and education, signlanguages have a key role to play for linguistics in general and forsemantics in particular. Despite earlier misconceptions that deniedthem the status of full-fledged languages, their grammar, theirexpressive possibilities, and their brain implementation are overallstrikingly similar to those of spoken languages (Sandler &Lillo-Martin 2006; MacSweeney et al. 2008). In other words, humanlanguage exists in two modalities, signed and spoken, and any generaltheory must account for both, a view that is accepted in all areas oflinguistics.

Cross-linguistic semantics is thus naturally concerned with signlanguages. In addition, sign languages (or ‘sign’ forshort) raise several foundational questions. These include cases of‘Logical Visibility’, cases of iconicity, and thepotential universal accessibility of certain properties of the signmodality.

Historically, a number of notable early works in sign languagesemantics have taken a similar argumentative form, proposing thatcertain key components of Logical Forms that are covert in speechsometimes have an overt reflex in sign (‘LogicalVisibility’). Such arguments have been formulated for diversephenomena such as variables, context shift, and telicity. Theirsemantic import is clear: if a logical element is indeed overtlyrealized, it has ramifications for the inventory of the logicalvocabulary of human language, and indirectly for the types of entitiesthat must be postulated in semantic models (‘natural languageontology’, Moltmann 2017). Moreover, when a given element has anovert reflex, one can directly manipulate it in order to investigateits interaction with other parts of the grammar.

Arguments based on Logical Visibility are certainly not unique to signlanguage (e.g., see for instance Matthewson 2001 and Cable 2011 (seeOther Internet Resources) for the importance of semantic fieldwork forspoken languages), nor do they entail that sign languages as a classwill make visible the same set of logical elements. Nevertheless, anotable finding from cross-linguistic work on sign languages is that anumber of the logical elements implicated in these discussions doindeed appear with a similar morphological expression across a largenumber of historically unrelated sign languages. Such observationsinvite deeper speculation about what it is about the signed modalitythat makes certain logical elements likely to appear in a givenform.

A second thread of semantically-relevant research relates to theobservation that sign languages make rich use of iconicity (Liddell2003; Taub 2001; Cuxac & Sallandre 2007), the property by which asymbol resembles its denotation by preserving some its structuralproperties. Sign language iconicity raises three foundationalquestions. First, some of the same semantic elements that areimplicated in arguments for Logical Visibility turn out to be employedand manipulated in the expression of concrete or abstract iconicrelations (e.g., pictorial uses of individual-denoting expressions;scalar structure; mereological structure), thus suggesting thatlogical and iconic notions are intertwined at the core of signlanguage. Second, sign languages have designated conventional words(‘classifier predicates’) whose position or movement mustbe interpreted iconically; this calls for an integration of techniquesfrom pictorial semantics into natural language semantics (Schlenker2018a; Schlenker & Lamberton forthcoming). Finally, this highdegree of iconicity raises questions about the comparison betweenspeech and sign, with the possibility that, along iconic dimensions,the latter is expressively richer (Goldin-Meadow & Brentari 2017;Schlenker 2018a).

Possibly due in part to the above factors, sign languages—evenwhen historically unrelated—behave as a coherent languagefamily, with several semantic properties in common that are notgenerally shared with spoken languages (Sandler & Lillo-Martin2006). Furthermore, some of these properties occasionally seem to be‘known’ by individuals that do not have access to signlanguage; these include hearing non-signers and also deaf homesigners(i.e., deaf individuals that are not in contact with a Deaf communityand thus have to invent signs to communicate with their hearingenvironment). Explaining this convergence is a key theoreticalchallenge.

Besides semantics proper, sign raises important questions for theanalysis of information structure, notably topic and focus. These areoften realized by way of facial articulators, including raisedeyebrows, which have sometimes been taken to play the same role assome intonational properties of speech (e.g., Dachkovsky & Sandler2009). For reasons of space, we leave these issues aside in whatfollows.

- 1. Logical Visibility I: Loci

- 2. Logical Visibility II: Beyond Loci

- 3. Iconicity I: Optional Iconic Modulations

- 4. Iconicity II: Classifier Predicates

- 5. Sign with Iconicity versus Speech with Gestures

- 6. Universal Properties of the Signed Modality

- 7. Future Issues

- Bibliography

- Academic Tools

- Other Internet Resources

- Related Entries

1. Logical Visibility I: Loci

In several cases of foundational interest, sign languages don’tjust have the same types of Logical Forms as spoken languages; theymay make overt key parts of the logical vocabulary that are usuallycovert in spoken language. These have been called instances of‘Logical Visibility’ (Schlenker 2018a; following theliterature, we use the term ‘logical’ loosely, to refer toprimitive distinctions that play a key role in a semanticanalysis).

- (1)

- Hypothesis: Logical Visibility

Sign languages can make overt parts of the logical/grammaticalvocabulary which (i) have been posited in the analysis of the LogicalForm of spoken language sentences, but (ii) are not morphologicallyrealized in spoken languages.

Claims of Logical Visibility have been made for logical variablesassociated with syntactic indices (Lillo-Martin & Klima 1990;Schlenker 2018a), for context shift operators (Quer 2005, 2013;Schlenker 2018a), and for verbal morphemes relevant to telicity(Wilbur 2003, 2008; Wilbur & Malaia 2008). In each case, the claimof Logical Visibility has been debated, and many questions remainopen.

In this section, we discuss cases in which logical variables ofdifferent types have been argued to sometimes be overt in sign—aclaim that has consequences of foundational interest for semantics; wewill discuss further potential cases of Logical Visibility in the nextsection.

In English and other languages, sentences such as(2a) and(3a) can be read in three ways (see(2b)–(3b)), depending on whether the embedded pronoun is understood to depend onthe subject, on the object, or to refer to some third person.

- (2)

- a.

- Sarkozyi told Obamak thathei/k/m would be re-elected.

- b.

- Sarkozy \(\lambda i\) Obama \(\lambda k\, t_i\) told \(t_k\) thathei/k/m would be re-elected.

- (3)

- a.

- [A representative]i told [asenator]k that hei/k/m would bere-elected.

- b.

- [a representative]i \(\lambda i\) [asenator]k \(\lambda k\, t_i\) told \(t_k\) thathei/k/m would be re-elected

A claim of Logical Visibility relative to variables has been made insign because one can introduce a separate position in signing space,or ‘locus’ (plural ‘loci’), for each of theantecedents (e.g., Sarkozy on the left and Obama on the right for(2)), and one can then point towards these loci (towards the left ortowards the right) to realize the pronoun: loci thus mirror the roleof variables in these examples.

1.1 Loci as visible variables?

Sign languages routinely use loci to represent objects or individualsone is talking about. Pronouns can be realized by pointing towardsthese positions. The signer and addressee are represented in a fixedposition that corresponds to their real one, and similarly for thirdpersons that are present in the discourse situation: one points atthem to refer to them. But in addition, arbitrary positions can becreated for third persons that are not present in the discourse. Themaximum number of loci that can be simultaneously used seems to bedetermined by considerations of performance (e.g., memory) rather thanby rigid grammatical conditions (there are constructed examples withup to 7 loci in the literature).

- (4)

Loci corresponding to the signer (1), the addressee (2), and differentthird persons (3a and 3b) (from Pfau, Salzmann, & Steinbach 2018:Figure 1)

We focus on the description of loci in American Sign Language (ASL)and French Sign Language (LSF, for ‘Langue des SignesFrançaise’), but these properties appear in asimilar form across the large majority of sign languages. Singularpronouns are signed by directing the index finger towards a point inspace; plural pronouns can be signed with a variety of strategies,including using the index finger to trace a semi-circle around an areaof space, and are typically used to refer to groups of at least threeentities. Other pronouns specify a precise number of participants withan incorporated numeral (e.g., dual, trial), and move between two ormore points in space. In addition, some verbs, called ‘agreementverbs’, behave as if they contain a pronominal form in theirrealization, pertaining to the subject and/or to the object. Forinstance,TELL in ASL targets different positions dependingon whether the object is second person(5a) or third person(5b).

- (5)

- An object agreement verb in ASL

(a) I tell you.

Credits: © Dr. Bill Vicars:TELL in ASL (description with short video clip, no audio)

(b) I tell him/her

Loci often make it possible to disambiguate pronominal reference. Forinstance, the ambiguity of the example in(2) can be removed in LSF, where the sentence comes in two versions. Inboth, Sarkozy is assigned a locus on the signer’s left (by wayof the index of the left hand held upright,‘👆left’below), andObama a locus on the right (using the index of the right hand heldupright,‘👆right’below).The verbtell inhe (Sarkozy) tells him (Obama) isrealized as a single sign linking the Sarkozy locus on the left to theObama locus on the right (unlike the ASL version, which just displaysobject agreement, the LSF version displays both subject and objectagreement: ‘leftTELLright’ indicatesthat the sign moves from the Sarkozy locus on the left to the Obamalocus on the right). Ifhe refers to Sarkozy, the signerpoints towards the Sarkozy locus on the left(‘👉left’);ifhe refers to Obama, the signer points towards the Obama locuson the right(‘👉right’).

- (6)

SARKOZY 👆left OBAMA 👆rightleftTELLright

‘Sarkozy told Obama…- a.

- 👉left WILL WIN ELECTION.

that he, Sarkozy, would win the election.’ - b.

- 👉right WILL WIN ELECTION.

that he, Obama, would win the election.’

In sign language linguistics, signs are transcribed in capitalletters, as was the case above, and loci are encoded by way of letters(a,b,c, …), starting from thesigner’s dominant side (right for a right-handed signer, leftfor a left-handed signer). The upward fingers used to establishpositions for Sarkozy and Obama are called ‘classifiers’and are glossed here asCL (with the conventions ofSection 4.2. the gloss would bePERSON-cl; classifiers are just one wayto establish the position of antecedents, and they are not essentialhere). Pronouns involving pointing with the index finger are glossedasIX. With these conventions, the sentence in(6) can be represented as in(7). (Examples are followed by the name of the language, as well as thereference of the relevant video when present in the original source;thus ‘LSF 4, 235’ indicates that the sentence is from LSF,and can be found in the video referenced as 4, 235.)

- (7)

- SARKOZY CLb OBAMA CLab-TELL-a {IX-b / IX-a} WILL WIN ELECTION.

‘Sarkozy told Obama that he, {Sarkozy/Obama}, would win theelection.’ (LSF 4, 235)

The ambiguity of quantified sentences such as(3) can also be removed in sign, as illustrated in an LSF sentence in(8).

- (8)

- DEPUTYb SENATORaCLb-CLa IX-ba-TELL-b {IX-a / IX-b} WIN ELECTION

‘An MPb told a senatora thathea / heb (= the deputy) would winthe election.’ (LSF 4, 233)

In light of these data, the claim of Logical Visibility is that signlanguage loci (when used—for they need not be) are an overtrealization of logical variables.

One potential objection is that pointing in sign might be verydifferent from pronouns in speech: after all, one points whenspeaking, but pointing gestures are not pronouns. However thisobjection has little plausibility in view of formal constraints thatare shared between pointing signs and spoken language pronouns. Forexample, pronouns in speech are known to follow grammaticalconstraints that determine which terms can be used in whichenvironments (e.g., the non-reflexive pronounher when theantecedent is ‘far enough’ vs. the reflexive pronounherself when the antecedent is ‘close enough’).Pointing signs obey similar rules, and enter into an establishedtypology of cross-linguistic variation. For instance, the ASLreflexive displays the same kinds of constraints as the Mandarinreflexive pronoun in terms of what counts as ‘closeenough’ (see Wilbur 1996; Koulidobrova 2009; Kuhn 2021).

It is thus generally agreed that pronouns in sign are part of the sameabstract system as pronouns in speech. It is also apparent that lociplay a similar function to logical variables, disambiguatingantecedents and tracking reference. This being said, the claim thatloci are a direct morphological spell-out of logical variablesrequires a more systematic evaluation of the extent to which signlanguage loci have the formal properties of logical variables. As aconcrete counterpoint, one observes that gender features in Englishalso play a similar function, disambiguating antecedents andtracking reference. For instance,Joe Biden told Kamala Harristhat he would be elected has a rather unambiguous reading(he =Biden), whileJoe Biden told Kamala Harristhat she would be elected has a different one (she =Harris). Such parallels have led some linguists to proposethat loci should best be viewed as grammatical features akin to genderfeatures (Neidle et al. 2000; Kuhn 2016).

As it turns out, sign language loci seem to share some properties withlogical variables, and some properties with grammatical features. Onthe one hand, the flexibility with which loci can be used seems closerto the nature of logical variables than to grammatical features.First, gender features are normally drawn from a finite inventory,whereas there seems to be no upper bound to the number of loci usedexcept for reasons of performance. Second, gender features have afixed form, whereas loci can be created ‘on the fly’ invarious parts of signing space. On the other hand, loci may sometimesbe disregarded in ways that resemble gender features. A large part ofthe debate has focused on sign language versions of sentences such as: Only Ann did her homework. This has a salient (‘boundvariable’) reading that entails thatBill didn’t dohis homework. In order to derive this reading,linguists have proposed that the gender features of the pronounher must be disregarded, possibly because they are the resultof grammatical agreement. Loci can be disregarded in the very samekind of context, suggesting that they are features, not logicalvariables (Kuhn 2016). In light of this theoretical tension, apossible synthesis is that loci are a visible realization of logicalvariables, but mediated by a featural level (Schlenker 2018a). Thedebate continues to be relatively open.

While there has been much theoretical interest in cases in whichreference is disambiguated by loci, this is usually an option, not anobligation. In ASL, for instance, it is often possible to realizepronouns by pointing towards a neutral locus that need not beintroduced explicitly by nominal antecedents, and in fact severalantecedents can be associated with this default locus. This gives riseto instances of referential ambiguity that are similar to those foundin English in (2)–(3) above (see Frederiksen & Mayberry2022; for an account that treats loci as corresponding to entireregions of signing space, and also allows for sign language pronounswithout locus specification, see Steinbach & Onea 2016).

1.2 Time and world-denoting loci

Regardless of implementation, the flexible nature of sign languageloci allows one to revisit foundational questions about anaphora andreference.

In the analysis of temporal and modal constructions in speech, thereare two broad directions. One goes back to quantified tense logic andmodal logic, and takes temporal and modal expressions of naturallanguage to be fundamentally different from individual-denotingexpressions: the latter involve the full power of variables andquantifiers, whereas no variables exist in the temporal and modaldomain, although operators manipulate implicit parameters. Theopposite view is that natural language has in essence the same logicalvocabulary across the individual, the temporal and the modal domains,with variables (which may take different forms across differentdomains) and quantifiers that may bind them (see for instance vonStechow 2004). This second tradition was forcefully articulated byPartee (1973) for tense and Stone (1997) for mood. Partee’s andStone’s argument was in essence that tense and mood havevirtually all the uses that pronouns do. This suggests,theory-neutrally, that pronouns, tenses and moods have a commonsemantic core. With the additional assumption that pronouns should beassociated with variables, this suggests that tenses and moods shouldbe associated with variables as well, perhaps with time- andworld-denoting variables, or with a more general category ofsituation-denoting variables.

As an example, pronouns can have a deictic reading on which they referto salient entities in the context; if a person sitting alone withtheir head in their hands utters:She left me, one willunderstand thatshe refers to the person’s formerpartner. Partee argued that tense has deictic uses too. For instance,if an elderly author looks at a picture selected by their publisherfor a forthcoming book, and says:I wasn’t young, onewill understand that the author wasn’t youngwhen thepicture was taken. Stone similarly argued that mood can havedeictic readings, as in the case of someone who, while looking at ahigh-end stereo in a store, says:My neighbors would kill me.The interpretation is that the speaker’s neighbors would(metaphorically) kill them “if the speaker bought the stereo andplayed it a ‘satisfying’ volume”, in Stone’swords. A wide variety of other uses of pronouns can similarly bereplicated with tense and mood, such as cross-sentential binding withindefinite antecedents. (In the individual domain:A woman will goto Mars. She [=the woman who goes to Mars] will be famous. In thetemporal domain:I sometimes go to China. I eat Peking duck [=inthe situations in which I visit China].)

While strong, these arguments are indirect because theformof tense and mood looks nothing like pronouns. In several signlanguages, including at least ASL (Schlenker 2018a) and Chinese SignLanguage (Lin et al. 2021), loci provide a more direct argumentbecause in carefully constructed examples, pointing to loci can beused not just to refer to individuals, but also to temporal and modalsituations, with a meaning akin to that of the wordthen inEnglish. It follows that the logical system underlying the ASLpronominal system (e.g., as variables) extends to temporal and modalsituations.

A temporal example appears in(9). In the first sentence,SOMETIMES WIN is signed in a locusa. In the second sentence, the pointing signIX-arefers back to the situations in which I win. The resulting meaning isthat I am happyin those situations in which I win, not ingeneral; this corresponds to the reading obtained with the wordthen in English: ‘then I am happy’. (Here andbelow, ‘re’ glosses raised eyebrows, with a line above thewords over which eyebrow raising occurs.)

- (9)

Context: Every week I play in a lottery.

IX-1 [SOMETIMESWIN]a. IX-are IX-1 HAPPY.

‘Sometimes I win. Then I am happy.’ (ASL 7, 202)

Formally,SOMETIMES can be seen as an existential quantifierover temporal situations, so the first sentence is semanticallyexistential:there are situations in which I win. Thepointing sign thus displays cross-sentential anaphora, depending on atemporal existential quantifier that appears in a preceding sentence.A further point made by Chinese Sign Language (but not by the ASLexample above) is that loci may be ordered on a temporal line, withthe result that not just the loci but also their ordering can be madevisible (Lin et al. 2021).

A related argument can be made about anaphoric reference to modalsituations: in(10), the second sentence just asserts that there are possible situationsin which I am infected, associating the locusa with situationsof infection. The second sentence makes reference to them: in thosesituations (not in general), I have a problem. Here too, the readingobtained corresponds to a use of the wordthen inEnglish.

- (10)

- FLU SPREAD. IX-1 POSSIBLE INFECTEDa.IX-are IX-1 PROBLEM.

‘There was a flu outbreak. I might get infected. Then I have aproblem.’ (ASL 7, 186)

In sum, temporal and modal loci make two points. First,theory-neutrally, the pointing sign can have both the use of Englishpronouns and of temporal and modal readings of the wordthen,suggesting that a single system of reference underlies individual,temporal and modal reference. Second, on the assumption that loci arethe overt realization of some logical variables, sign languagesprovide a morphological argument for the existence of temporal andmodal variables alongside individual variables.

1.3 Degree-denoting loci

In spoken language semantics, there is a related debate about theexistence of degree-denoting variables. The English sentencesAnnis tall andAnn is taller than Bill (as well as othergradable constructions) can be analyzed in terms of reference todegrees, for instance as in(11).

- (11)

- a.

- Ann is tall.

the maximal degree to which Ann is tall ≥ the threshold for‘tall’ - b.

- Ann is taller than Bill.

the maximal degree to which Ann is tall ≥ the maximal degree towhich Bill is tall

To say that onecan analyze the meaning in terms of referenceto degrees doesn’t entail that one must (for discussion, seeKlein 1980). And even if one posits quantification over degrees, afurther question is whether natural language has counterparts ofpronouns that refer to degrees—if so, one would have an argumentthat natural language is committed to degrees. Importantly, thisdebate is logically independent from that about the existence of time-and world-denoting pronominals, as one may consistently believe thatthere are pronominals in one domain but not in the other. The questionmust be asked anew, and here too sign language brings importantinsights.

Degree-denoting pronouns exist in some constructions of Italian SignLanguage (LIS; Aristodemo 2017). In(12), the movement of the signTALL ends at a particular locationon the vertical axis (which we call α, to avoid confusion withthe Latin characters used for individual loci in the horizontalplane), which intuitively represents Gianni’s degree of height.In the second sentence, the pronoun points towards thisdegree-denoting locus, and the rest of the sentence characterizes thisdegree of height.

- (12)

- GIANNI TALL\(_{\alpha}\). IX-\(\alpha\) 1 METER 70

‘Gianni is tall. His height is 1.70 meters.’ (Aristodemo2017: example 2.23)

More complicated examples can be constructed in whichAnn istaller than Bill makes available two degree-denoting loci, onecorresponding to Ann’s height and the other to Bill’s.

In sum, some constructions of LIS provide evidence for the existenceof degree-denoting pronouns in sign language, which in turn suggeststhat natural language is sometimes committed to the existence ofdegrees. And if one grants that loci are the realization of variables,one obtains the further conclusion that natural language has at leastsome degree-denoting variables. (It is a separate question whether alllanguagesavail themselves of degree variables; see Beck etal. 2009 for the hypothesis that this is a parameter of semanticvariation.)

Finally, we observe that, unlike the examples of individual-denotingpronouns seen so far, the placement of degree pronouns along aparticular axis is semantically interpreted, reflecting the totalordering of their denotations: not only are degrees visibly realized,but so is their ordering (see alsoSection 1.3 regarding the ordering on temporal loci on timelines in Chinese SignLanguage, andSection 3.4 for a discussion of a structural iconicity).

In sum, loci have been argued to be the overt realization ofindividual, time, world, and degree variables. If one grants thispoint, it follows that sign language is ontologically committed tothese object types. But the debate is still ongoing, with alternativesthat take loci to be similar to features rather than to variables. Letus add that the loci-as-variable analysis has offered a new argumentin favor of dynamic semantics, where a variable can depend on aquantifier without being in its syntactic scope; see thesupplement on Dynamic Loci.

2. Logical Visibility II: Beyond Loci

There are further cases in which sign language arguably makes visiblesome components of Logical Forms that are not always overt in spokenlanguage.

2.1 Telicity

Semanticists traditionally classify event descriptions astelic if they apply to events that have a natural endpointdetermined by that description, and they call thematelicotherwise.Ann arrived andMary understood have sucha natural endpoint, e.g., the point at which Ann reached herdestination, and that at which Mary saw the light, so to speak:arrive andunderstand are telic. By contrast,Ann waited andMary thought lack such naturalendpoints:wait andthink are atelic. As a standardtest (e.g., Rothstein 2004), a temporal modifier of the formin Xtime modifies telic VPs whilefor X time modifies atelicVPs (e.g.,Ann arrived in five minutes vs. Ann waitedfor five minutes,Mary understood in a second vs.Mary thought for a second).

Telicity is a property of predicates (i.e., verbs complete witharguments and modifiers), not of verbs themselves. Whether a predicateis telic or atelic may thus result from a variety of differentfactors; these include adverbial modifiers that explicitly identify anendpoint—run 10 kilometers (in an hour) is telic, butrun back and forth (for an hour) is atelic—andproperties of the nominal arguments—eat an apple (in twominutes) is telic whereaseat lentil soup (for twominutes) is atelic. But telicity also depends on properties ofthe lexical semantics of the verb itself, as illustrated by theintransitive verbs above, as well as transitive examples likefound a solution (in an hour) versuslook for a solution(for an hour). In work on spoken language, some theorists haveposited that these lexical factors can be explained by a morphologicaldecomposition of the verb, and that inherently telic verbs likearrive orfind include a morpheme that specifies theendstate resulting from a process (Pustejovsky 1991; Ramchand 2008).This morpheme has been called various things in the literature,including ‘EndState’ (Wilbur 2003) and ‘Res’(Ramchand 2008).

In influential work, Wilbur (2003, 2008; Wilbur & Malaia 2008) hasargued that the lexical factors related to telicity are often realizedovertly in the phonology of several sign languages: inherently telicverbs tend to be realized with sharp sign boundaries; inherentlyatelic verbs are realized without them (Wilbur 2003, 2008; Wilbur& Malaia 2008). For instance, the ASL signARRIVEinvolves a sharp deceleration, as one hand makes contact with theother, as shown in(13).

- (13)

ARRIVE in ASL (telic)

Short video clip of ARRIVE (ASL), no audio

Picture credits: Valli, Clayton: 2005,The GallaudetDictionary of American Sign Language, Gallaudet UniversityPress.

In contrast,WAIT is realized with a trilled movement of thefingers and optional circular movement of the hands, without a sharpboundary:

- (14)

WAIT in ASL (atelic)

Short video clip of WAIT (ASL), no audio

Picture credits: Valli, Clayton: 2005,The GallaudetDictionary of American Sign Language, Gallaudet UniversityPress.

Similarly, in LSFUNDERSTAND, which is telic, is realizedwith three fingers forming a tripod that ends up closing on theforehead; the closure is realized quickly, and thus displays a sharpboundary. By contrast,REFLECT, which is atelic, is realizedby the repeated movement of the curved index finger towards thetemple, without sharp boundaries.

- (15)

- a.

- UNDERSTAND (LSF)

- b.

- REFLECT (LSF)

Credits: La langue des signes - dictionnaire bilingueLSF-français. IVT 1986

Wilbur (2008) posits that in ASL and other sign languages, thisphonological cue, the “rapid deceleration of the movement to acomplete stop”, is an overt manifestation of the morphemeEndState, yielding inherently telic lexical predicates. IfWilbur’s analysis is correct, this is another possible instanceof visibility of an abstract component of Logical Forms that is notusually overt in spoken languages. An alternative is that an abstractversion of iconicity is responsible for this observation (Kuhn 2015),as we will see inSection 3.2.

It is also possible that the analysis of this phonological cue variesacross languages. Of note, both ASL and LSF have exceptions to thegeneralization (Davidson et al. 2019), for example ASLSLEEPis atelic but ends with deceleration and contact between the fingers;LSFRESIDE is similarly atelic but ends with deceleration andcontact. In contrast, in Croatian Sign Language (HZJ), endmarkingappears to be a regular morphological process, allowing a verb stem toalternate between an end-marked and non-endmarked form (Milković2011).

2.2 Context shift

In the classic analysis of indexicals developed by Kaplan (1989), thevalue of an indexical (words likeI,here, andnow) is determined by a context parameter that cruciallydoesn’t interact with time and world operators (in other words,the context parameter is not shiftable). The empirical force of thisidea can be illustrated by the distinction betweenI, anindexical, andthe person speaking, which is indexical-free.The speaker is always late may, on one reading, refer todifferent speakers in different situations becausespeakercan be evaluated relative to a time quantified byalways.Similarly,The speaker must be late can be uttered even ifone has no idea who the speaker is supposed to be; this is becausespeaker can be evaluated relative to a world quantified bymust. By contrast,I am always late andI mustbe late disallow such a dependency becauseI isdependent on the context parameter alone, not on time and worldquantification. This analysis raises a question: are there anyoperators that can manipulate the context of evaluation of indexicals?While such operators can be defined for a formal language, Kaplanfamously argued that they do not exist in natural language and calledthem, for this reason, ‘monsters’.

Against this claim, an operator of ‘context shift’ (aKaplanian monster) has been argued to exist in several spokenlanguages (including Amharic and Zazaki). The key observation was thatsome indexicals can be shifted in the scope of some attitude verbs,and in the absence of quotation (e.g., Anand & Nevins 2004; Anand2006; Deal 2020). Schematically, in such languages,Ann says thatI am a hero can mean that Ann says that she herself is a hero,withI interpreted from Ann’s perspective. Severalresearchers have argued that context shift can be overt in signlanguage, and realized by an operation called ‘RoleShift’, whereby the signer rotates her body to adopt theperspective of another character (Quer 2005, 2013; Schlenker 2018a).

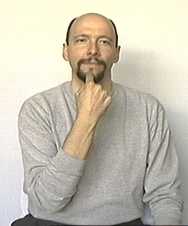

A simple example involves the sentenceWIFE SAYIX-2FINE, where the boldfaced words are signed from therotated position, illustrated below. As a result, the rest of thesentence is interpreted from the wife’s perspective, with theconsequence that the second person pronounIX-2 refers towhoever the wife is talking to, and not the addressee of the signer.

- (16)

An example of Role Shift in ASL (Credits: Lillo-Martin2012)

WIFE SAYIX-2 FINE

Role Shift exists in several languages, and in some cases (notably inCatalan and German sign languages [Quer 2005; Herrmann & Steinbach2012]), it has been argued not to involve mere quotation. On thecontext-shifting analysis of Role Shift (e.g., Quer 2005, 2013), thepoint at which the signer rotates her body corresponds to theinsertion of a context-shifting operator C, yielding therepresentation: WIFE SAY C [IX-2 FINE]. The boldfacedwords are signed in rotated position and are taken to be interpretedin the scope of C.

Interestingly, Role Shift differs from context-shifting operationsdescribed in speech in that it can be used outside of attitude reports(to distinguish the two cases, researchers use the term‘Attitude Role Shift’ for the case we discussed before,and ‘Action Role Shift’ for the non-attitudinal case). Forexample, if one is talking about an angry man who has been establishedat locusa, one can use an English-strategy and sayIX-aWALK-AWAY to mean that he walked away. But an alternativepossibility is to apply Role Shift after the initial pointing sign,and say the following (with the operatorC realized by thesigner’s rotation):

- (17)

- IX-a C [1-WALK-AWAY].

Here1-WALK-AWAY is a first person versionof ‘walk away’, but the overall meaning is just that theangry person associated with locusa walked away. By performinga body shift and adopting that person’s position to sign1-WALK-AWAY, the signer arguably makes the description morevivid.

Importantly, in ASL and LSF, Role Shift interacts with iconicity.Attitude Role Shift has, at a minimum, a strong quotational component.For instance, angry facial expressions under Role Shift must beattributed to the attitude holder, not to the signer (Schlenker2018a). This observation extends to ASL and LSF Action Role Shift:disgusted facial expressions under Action Role Shift are attributed tothe agent rather than to the signer.

As in other cases of purported Logical Visibility, the claim that RoleShift is the visible reflex of an operation that is covert in speechhas been challenged. In the analysis of Davidson (2015, followingSupalla 1982), Role Shift falls under the category of classifierpredicates, specific constructions of sign language that areinterpreted in a highly iconic fashion (we discuss them inSection 4). What is special about Role Shift is that the classifier is not signedwith a hand (as other classifiers are), but with the signer’sown body. The iconic nature of this classifier means that propertiesof role-shifted expressions that can be iconically assigned to thedescribed situation must be. For Attitude Role Shift, the analysisessentially derives a quotational reading via ademonstration—for our example above, something like:My wifesaid this, “You are fine”. Cases of Attitude RoleShift that have been argued not to involve standard quotation ( inCatalan and German sign language) require refinements of the analysis.For Action Role Shift, the operation has the effect of demonstratingthose parts of signs that are not conventional, yielding in essence:He walked away like this, wherethis refers to alliconically interpretable components of the role-shifted construction(including the signer’s angry expression, if applicable).

Debates about Role Shift have two possible implications. On one view,Role Shift provides overt evidence for context shift, and extends thetypology of Kaplanian monsters beyond spoken languages and beyondattitude operators (due to the existence of Action Role Shiftalongside Attitude Role Shift). On the alternative view developed byDavidson, Role Shift suggests that some instances of quotation shouldbe tightly connected to a broader analysis of iconicity owing to thesimilarity between Attitude Role Shift an Action Shift.

In sum, it has been argued that telicity and context shift can beovertly marked in sign language, hence instances of Logical Visibilitybeyond loci, but alternative accounts exist as well. Let us add thatthere are cases of Logicalnon-visibility, in which logicalelements that are often overt in speech can be covert in sign. See thesupplement on Coordination for the case of an ASL construction ambiguous between conjunction anddisjunction.

3. Iconicity I: Optional Iconic Modulations

On a standard (Saussurean) view, language is made of discreteconventional elements, with iconic effects at the margins. Signlanguages cast doubt on this view because iconicity interacts incomplex and diverse ways with grammar.

By iconicity, we mean a rule-governed way in which an expressiondenotes something by virtue of its resemblance to it, as is forinstance the case of a photograph of a cat, or of a vocal imitation ofa cat call. By contrast, the conventional wordcat does notrefer by resembling cats. There are also mixed cases in which anexpression has both a conventional and an iconic component.

In this section and the next, we survey constructions that displayoptional or obligatory iconicity in sign, and call for the developmentof a formal semantics with iconicity. As we will see, some purportedcases of Logical Visibility might be better analyzed as more or lessabstract versions of iconicity, with the result that several phenomenadiscussed above can be analyzed from at least two theoreticalperspectives.

3.1 Iconic modulations

As in spoken language, it is possible to modulate some conventionalwords in an iconic fashion. In English,the talk was looongsuggests that the talk wasn’t just long butvery long.Similarly, the conventional verbGROW in ASL can be realizedmore quickly to evoke a faster growth, and with broader endpoints tosuggest a larger growth, as is illustrated below (Schlenker 2018b).There are multiple potential levels of speed and endpoint breadth,which suggests that a rule is genuinely at work in this case.

- (18)

Different iconic modulations of the signGROW in ASL(Picture credits: M. Bonnet)

Slow movement Fast movement Narrow

endpoints

small amount,

slowlysmall amount,

quicklyMedium

endpoints

medium amount,

slowlymedium amount,

quicklyBroad

endpoints

large amount,

slowlylarge amount,

quickly

In English, iconic modulations can arguably be at-issue and thusinterpreted in the scope of grammatical operators. An example is thefollowing sentence:If the talk is loooong,I’llleave before the end. This means that if the talk is very long,I’ll leave before the end (but if it’s only moderatelylong, maybe not); here, the iconic contribution is interpreted in thescope of theif-clause, just like normal at-issuecontributions. The iconic modulation ofGROW has similarlybeen argued to be at-issue (Schlenker 2018b). (SeeSection 5.2 for further discussion on the at-issue vs. non-at-issue semanticcontributions.)

While conceptually similar to iconic modulations in English, the signlanguage versions are arguably richer and more pervasive than theirspoken language counterparts.

3.2 Event structure

Iconic modulation interacts with the marking of telicity noticed byWilbur (Section 2.1).GROW, discussed in the preceding sub-section, is an (atelic)degree achievement; the iconic modifications above indicate the finaldegree reached and the time it took to reach that degree. Similarly,for telic verbs, the speed and manner in which the phonologicalmovement reaches its endpoint can indicate the speed and manner inwhich the result state is reached. For example, if LSFUNDERSTAND is realized slowly and then quickly, the resultingmeaning is that there was a difficult beginning, and then an easierconclusion. Atelic verbs that don’t involve degrees can also beiconically modulated; for instance, if LSFREFLECT is signedslowly and then quickly, the resulting meaning is that theperson’s reflection intensified. Here too, the iconiccontribution has been argued to be at-issue (Schlenker 2018b).

There are also cases in which the event structure is not justspecified but radically altered by a modulation, as in the case ofincompletive forms (also called unrealized inceptive, Liddell 1984;Wilbur 2008). ASLDIE, a telic verb, is expressed by turningthe dominant hand palm-down to palm-up as shown below (thenon-dominant hand turns palm-up to palm-down). If the hands only turnpartially, the sign is roughly interpreted as ‘almostdie’.

- (19)

Normal vs. incompletive form ofDIE in ASL (Credits:J. Kuhn)

a. DIE in ASL

b. ALMOST-DIE in ASL

Similarly to the fact that multiple levels of speed and size can beindicated by the verbGROW in(18), the incompletive form of verbs can be modulated to indicatearbitrarily many degrees of completion, depending on how far the handtravels; these examples thus seem to necessitate an iconic rule (Kuhn2015). On the other hand, while the examples withGROW can beanalyzed by simple predicate modification (‘The group grew andit happened like this: slowly’), examples of incompletivemodification require a deeper integration in the semantics, similar tothe semantic analysis of the adverbalmost or the progressiveaspect in English. (Notably, it’s nonsense to say: ‘Mygrandmother died and it happened like this: incompletely.’)

The key theoretical question lies in the integration between iconicand conventional elements in such cases. If one posits adecompositional analysis involving a morpheme representing theendstate (EndState orRes, seeSection 2.1), one must certainly add to it an iconic component (with a non-trivialchallenge for incompletive forms, where the iconic component does notjust specify but radically alters the lexical meaning). Alternatively,one may posit that a structural form of iconicity is all one needs,without morphemic decomposition. An iconic analysis along these lineshas been proposed (Kuhn 2015: Section 6.5), although a full accounthas yet to be developed.

3.3 Plurals and pluractionals

The logical notion of plurality is expressed overtly in some way inmany of the world’s languages: pluralizing operations may applyto nouns or verbs to indicate a plurality of objects or events (fornouns: ‘plurals’; for verbs: ‘pluractionals’).Historically, arguments of Logical Visibility have not been made forplurals in sign languages, since—while overt plural markingcertainly exists in sign language—plural morphemes also appearovertly in spoken languages (e.g., English singularhorse vs.pluralhorses).

Nevertheless, mirroring areas of language in which arguments ofLogical Visibilitydo apply, plural formation in signlanguage shows a number of unique and revealing properties. First, themorphological expression of this logical concept is similar for bothnouns and verbs across a large number of unrelated sign languages: forboth plural nouns (Pfau & Steinbach 2006) and pluractional verbs(Kuhn & Aristodemo 2017), plurality is expressed by repetition. Wenote that repetition-based plurals and pluractionals also exist inspeech (Sapir 1921: 79).

Second, in sign language, these repeated plural forms have been shownto feed iconic processes. Modifications of the way in which the signis repeated may indicate the number of objects or events, or mayindicate the arrangement of these pluralities in space or time.Relatedly, so-called ‘punctuated’ repetitions (with clearbreaks between the iterations) refer to precise plural quantities(e.g., three objects or events for three iterations), while‘unpunctuated’ repetitions (without clear breaks betweenthe iterations) refer to plural quantities with vague thresholds, andoften ‘at least’ readings (Pfau & Steinbach 2006;Schlenker & Lamberton 2022).

In the nominal domain, the number of repetitions may provide anindication of the number of objects, and the arrangement of therepetitions in signing space can provide a pictorial representation ofthe arrangement of the denotations in real space (Schlenker &Lamberton 2022). For instance, the wordTROPHY can beiterated three times on a straight line to refer to a group oftrophies that are horizontally arranged; or the three iterations canbe arranged as a triangle to refer to trophies arranged in atriangular fashion. A larger number of iterations serves to refer tolarger groups. Here too, the iconic contribution can be at-issue andthus be interpreted in the scope of logical operators such asif-clauses.

- (20)

- a.

TROPHY in ASL, repetition on a line:

- b.

TROPHY in ASL, repetition as a triangle:

Credits: M. Bonnet

Punctuated (= easy to count) repetitions yield meanings with precisethresholds (often with an ‘exactly’ reading, e.g.,‘exactly three trophies’ for three punctuated iterations);unpunctuated repetitions yield vague thresholds and often ‘atleast’ readings (e.g., ‘several trophies’ for threeunpunctuated iterations). While one may take the distinction to beconventional, it might have an iconic source. In essence, unpunctuatediterations result in a kind of pictorial vagueness on which thethreshold is hard to discern; deriving the full range of‘exactly’ and ‘at least’ readings isnon-trivial, however (Schlenker & Lamberton 2022).

In the verbal domain, pluractionals (referring to pluralities ofevents) can be created by repeating a verb, for instance in LSF andASL. A complete analysis seems to require both conventionalizedgrammatical components and iconic components. The form ofreduplication—as identical reduplication or as alternatingtwo-handed reduplication—appears to conventionally communicatethe distribution of events with respect to either time or toparticipants. But a productive iconic rule also appears to beinvolved, as the number and speed of the repetitions gives an idea ofthe number and speed of the denoted events (Kuhn & Aristodemo2017); again, the iconic contribution can be at-issue.

Iconic plurals and pluractionals alike are now treated by way of mixedlexical entries that include a grammatical/logical component and aniconic component. For instance, ifN is a (singular) noundenoting a set of entitiesS, then the iconic pluralN-rep denotes the set of entitiesx suchthat:

- x is the sum of atomic elements inS(i.e., \(x \in *S\)), and

- the form ofN-rep iconicallyrepresentsx.

Condition (i) is the standard definition of a plural;condition (ii) is the iconic part, which is itself in need of an elucidation usinggeneral tools of pictorial semantics (seeSection 4).

3.4 Iconic loci

Loci, which have been hypothesized to be (sometimes) the overtrealization of variables, can lead a dual life as iconicrepresentations. Singular loci may (but need not) be simplifiedpictures of their denotations: if so, a person-denoting locus is astructured areaI, and pronouns are directed towards a pointi that corresponds to the upper part of the body. In ASL, whenthe person is tall, one can thus point upwards (there are alsometaphorical cases in which one points upwards because the person ispowerful or important). When a person is understood to be in a rotatedposition, the direction of the pronoun correspondingly changes, asseen in(21) for a person standing upright or hanging upside down (Schlenker2018a; see also Liddell 2003).

- (21)

- An iconic locus schematically representing an upright person(left) or upside down person (right)

Iconic mappings involving loci may also preserve abstract structuralrelations that have been posited to exist for various kinds ofontological objects, including mereological relations, totalorderings, and domains of quantification.

First, two plural loci—indexed over areas of space—may(but need not) express mereological relations diagrammatically, with alocusa embedded in a locusb if the denotation ofa is a mereological part of the denotation ofb(Schlenker 2018a). For example, in(22), the ASL expressionPOSS-1 STUDENT (‘mystudents’) introduces a large locus (glossed asab tomake it clear that it contains sublocia andb—butinitially just a large locus).MOST introduces a sublocusa within this large locus because the plurality denoted bya is a proper part of that denoted byab. Andcritically, diagrammatic reasoning also makes available a thirddiscourse referent: when a plural pronoun points towardsb—the complement of the sublocusa within thelarge locusab—the sentence is acceptable, andbis understood to refer to the students who didnot come toclass.

- (22)

- POSS-1 STUDENT IX-arc-ab MOST IX-arc-aa-COME CLASS. IX-arc-bb-STAY HOME.

‘Most of my students came to class. They stayed home.’(ASL, 8, 196)

- (23)

In English, the plural pronounthey clearly lacks such areading when one says,Most of my students came to class. Theystayed home, which sounds contradictory. (One can communicate thetarget interpretation by saying,The others stayed home, butthe others is not a pronoun.) Likewise, in ASL, if the samediscourse is uttered using default, non-localized plural pronouns, thepattern of inferences is exactly identical to the Englishtranslation.

A second case of preservation of abstract orders pertains todegree-denoting and sometimes time-denoting loci. In LIS,degree-denoting loci are represented iconically, with the totalordering mapped to an axis in space, as described inSection 1.3. Time-denoting loci may but need not give rise to preservation ofordering on an axis, depending on whether normal signing space is used(as in the ASL examples(9) above), or a specific timeline, as mentioned inSection 1.2 in relation to Chinese Sign Language. As in the case of diagrammaticplural pronouns, the spatial ordering of degree- and time-denotingloci generates an iconic inference—beyond the meaning of thewords themselves—about the relative degree of a property ortemporal order of events.

A third case involves the partial ordering of domain restrictions ofnominal quantifiers: greater height in signing space may be mapped toa larger domain of quantification, as is the case in ASL (Davidson2015) and at least indefinite pronouns in Catalan Sign Language(Barberà 2015).

4. Iconicity II: Classifier Predicates

4.1 The demonstrative analysis of classifier predicates

A special construction type, classifier predicates(‘classifiers’ for short), has raised difficult conceptualquestions because they involve a combination of conventional andiconic meaning. Classifier predicates are lexical expressions thatrefer to classes of animate or inanimate entities that share somephysical characteristics—e.g., objects with a flat surface,cylindrical objects, upright individuals, sitting individuals, etc.Their form is conventional; for instance, the ASL ‘three’handshape, depicted below, represents a vehicle. But their position,orientation and movement in signing space is interpreted iconicallyand gradiently (Emmorey & Herzig 2003), as illustrated in thetranslation of the example below.

- (24)

- CAR CL-vehicle-DRIVE-BY. (ASL, Valli and Lucas 2000)

‘A car drove by [with a movement resembling that of thehand]

These constructions have on several occasions been compared togestures in spoken language, especially to gestures that fully replacesome words, as in:This airplane is about to FLY-take-off,with the verb replaced with a a hand gesture representing an airplanetaking off. But there is an essential difference: classifierpredicates are stable parts of the lexicon, gestures are not.

Early semantic analyses, notably by Zucchi 2011 and Davidson 2015,took classifier predicates to have a self-referential demonstrativecomponent, with the result that the moving vehicle classifier in(24) means in essence ‘move like this’, where‘this’ makes reference to the very form of the classifiermovement. As mentioned inSection 2.2, this analysis has been extended to Role Shift by Davidson (Davidson2015), who took the classifier to be in this case the signer’srotated body.

4.2 The pictorial analysis of classifier predicates

The demonstrative analysis of classifier predicates as stated has twogeneral drawbacks. First, it establishes a natural class containingclassifiers and demonstratives (like Englishthis), but thetwo phenomena possibly display different behaviors. Notably, whiledemonstratives behave roughly like free variables that can pick uptheir referent from any of a number of contextual sources, the iconiccomponent of classifiers can only refer to the position/movement andconfiguration of the hand (any demonstrative variable is thusimmediately saturated). Second, the demonstrative analysis currentlyrelegates the iconic component to a black box. Without anyinterpretive principles on what it means for an event to be‘like’ the demonstrated representation, one cannot provideany truth conditions for the sentence as a whole.

Any complete analysis must thus develop an explicit semantics for theiconic component. This is more generally necessary to derive explicittruth conditions from other iconic constructions in sign language,such as the repetition-based plurals discussed inSection 3.3. above: in the metalanguage, the condition[a certain expression]iconically represents [a certain object] was in need ofexplication.

A recent model has been offered by formal pictorial semantics,developed by Greenberg and Abusch (e.g., Greenberg 2013, 2021; Abusch2020). The basic idea is that a picture obtained by a given projectionrule (for instance, perspective projection) is true of precisely thosesituations that can project onto the picture. Greenberg has furtherextended this analysis with the notion of an object projecting onto apicture part (in addition to a situation projecting onto a wholepicture). This notion proves useful for sign language applicationsbecause they usually involve partial iconic representations, with oneiconic element representing a single object or event in a largersituation. To illustrate, below, the picture in(25a) is true of the situation in(25b), and the left-most shape in the picture in(25a) denotes the top cube in the situation in(25b).

- (25)

Illustration of a projection rule relating (parts of) a picture to(objects in) a world. (Credits: Gabriel Greenberg)

(a) Picture

(b) Situation

The full account makes reference to a notion of viewpoint relative towhich perspective projection is assessed, and a picture plane, bothrepresented in(25b). This makes it possible to say that the top cube (top-cube) projectsonto the left-hand shape (left-shape) relative to the viewpoint (callit π), at the timet and in the worldw in which theprojection is assessed. In brief:

\[\textrm{proj}(\textrm{top-cube}, \pi, t, w) = \textrm{left-shape}.\]Classifier predicates (as well as other iconic constructions, such asrepetition-based plurals) may be analyzed with a version of pictorialsemantics to explicate the truth-conditional contribution of iconicelements.

To illustrate, consider a pair of minimally different words in ASLthat can be translated as ‘airplane’: one is a normalnoun, glossed asPLANE, and the other is a classifierpredicate, glossed below asPLANE-cl. Both forms involve thehandshape in(26), but the normal noun includes a tiny repetition (different from thatof plurals) which is characteristic of some nominals in ASL. As wewill see, the position of the classifier version is interpretediconically (‘an airplane in position such and such’),whereas the nominal version need not be.

- (26)

Handshape for both (i) ASLPLANE (= nominal version) and (ii)ASLPLANE-cl (= classifier predicate version).(Credits: J. Kuhn)

Semantically, the difference between the two forms is that only theclassifier generates obligatory iconic inferences about theplane’s configuration and movement. This has clear semanticconsequences when several classifier predicates occur in the samesentence. In(27b), two tokens ofPLANE-cl appear in positionsa andb, and as the video makes clear, the two classifiers are signedclose to each other and in parallel. As a result, the sentence onlymakes an assertion about cases in which two airplanes take off next toeach other or side by side. In contrast, with a normal noun in(27a), the assertion is that there is danger whenever two airplanes take offat the same time, irrespective of how close the two airplanes are, orhow they are oriented relative to each other.

- (27)

- HERE ANYTIME __ SAME-TIME TAKE-OFF, DANGEROUS.

‘Here, whenever ___ take off at the same time, there isdanger.’- a.

- 7PLANEa PLANEb

‘two planes’ - b.

- 7PLANE-claPLANE-clb

‘two planes side by side/next to each other’

(ASL, 35, 1916, 4 judgments;short video clip of the sentences, no audio)

To capture these differences, one can posit the following lexicalentries for the normal noun and for its classifier predicate version.Importantly, the interpretation ofPLANE-cl in(28b) is defined for a particular token of the sign (not a type), producedwith a phonetic realization Φ.

- (28)

- For a contextc, time of evaluationt and world ofevaluationw:

- a.

- PLANE, normal noun

[[PLANE]]c,t,w = \(\lambda x_{e}\) .plane't,w(x) - b.

- PLANE-cl\(_{\Phi}\), classifier predicate [tokenwith phonetic realization \(\Phi\)]

[[PLANE-cl\(_{\Phi}\)]]c,t,w = \(\lambda x_{e}\) .plane't,w(x) and \(\boldsymbol{\textbf{proj}(x,\pi_{c}, t, w) = \Phi}\)

Evaluation is relative to a context c that provides the viewpoint,\(\pi_{c}\). In the lexical entry for the normal noun in(28a),plane't,w is a (metalanguage) predicate ofindividuals that applies to anything that is an airplane attinw. The classifier predicate has the lexical entry in(28b). It has the same conventional component as the normal noun, but addsto it an (iconic) projective condition: for a token of the predicatePLANE-cl to be true of an objectx,x shouldproject onto this very token.

4.3 Comparison and refinements

With this pictorial semantics in hand, we can make a more explicitcomparison to the demonstrative analysis of classifiers. As describedabove, a demonstrative analysis takes classifiers to include acomponent of meaning akin to ‘move like this’. For Zucchi,this is spelled out via a lexical entry very close to the one in(28), but in which the second clause (in terms of projection above) isinstead a similarity function, asserting that the position of thedenoted objectx is ‘similar’ to that of theairplane classifier; the proposal, however, leaves it entirely openwhat it means to be ‘similar’. Of course, one maysupplement the analysis with a separate explication in whichsimilarity is defined in terms of projection, but this movepresupposes rather than replaces an explicit pictorial account. Inother words, the demonstrative analysis relegates the iconic componentto a black box, whose content can be specified by the pictorialanalysis. But once a pictorial analysis is posited, it become unclearwhy one should make a detour through the demonstrative component,rather than posit pictorial lexical entries in the first place.

A number of further refinements need to be made to any analysis ofclassifiers. First, to have a fully explicit iconic semantics, onemust contend with several differences between classifiers andpictures.

- Classifier predicates have a conventional shape; only theirposition, orientation and movement is interpreted iconically(sometimes modifications of the conventional handshape can beinterpreted iconically as well). This requires projection rules with apartly conventional component (of the type: a certain symbol appearsin a certain position of the picture if an object of the right typesprojects onto that position).

- Many classifier predicates are dynamic (in the sense of involvingmovement) rather than static; this requires the development of asemantics for visual animations.

- Sign language classifiers are not two-dimensional pictures, butrather 3D representations. One can think of them as puppets whoseshape needn’t be interpreted literally, but whose position,orientation and movement can be iconically precise. This requiresformal means that go beyond pictorial semantics.

The interaction between iconic representations and the sentences theyappear in also requires further refinements. A first refinementpertains to the semantics. For simplicity, we assumed above that theviewpoint relative to which the iconic component of classifierpredicates is evaluated is fixed by the context. Notably, though, insome cases, viewpoint choice can be dependent on a quantifier. In theexample below, the meaning obtained is that in all classes, during thebreak,for some salient viewpoint π associated with theclass, there is a student who leaves with the movement depictedrelative to π; a recent proposal (Schlenker and Lambertonforthcoming) has viewpoint variables in the object language, and theymay be left free or bound by default existential quantifiers, asillustrated in(30). (While there is a strong intuition that Role Shift manipulatesviewpoints as well, a formal account has yet to be developed.)

- (29)

- Context: This school has 4 classrooms, one for each of 4teachers (each teacher always teaches in the same classroom).

CLASS BREAK ALL ALWAYS HAVE STUDENT PERSON-walk-back_right-cl.

‘In all classes, during the break, there is always a studentthat leaves toward the the back, to the right.’ (ASL, 35, 2254b;short video clip of the sentence, no audio) - (30)

- always \(\exists\pi\) there-is studentperson-walk-clπ

A second refinement pertains to the syntax. Across sign languages,classifier constructions have been shown to sometimes override thebasic word order of the language; for instance, ASL normally has thedefault word order SVO (Subject Verb Object), but classifierpredicates usually prefer preverbal objects instead. One possibleexplanation is that the non-standard syntax of classifiers arises atleast in part from their iconic semantics; we revisit this point inSection 5.3.

5. Sign with Iconicity versus Speech with Gestures

5.1 Reintegrating gestures in the sign/speech comparison

The iconic contributions discussed above are to some extent differentfrom those found in speech. Iconic modulations exist in speech (e.g.,looong means ‘very long’) but are probably lessdiverse than those found in sign. Repetition-based plurals andpluractionals exist in speech (Rubino 2013), and it has been arguedfor pluractional ideophones in some languages, that the number ofrepetitions can reflect the number of denoted events (Henderson 2016).But sign language repetitions can iconically convey a particularlyrich amount of information, including through their punctuated orunpunctuated nature, and sometimes their arrangement in space(Schlenker & Lamberton 2022). As for iconic pronouns andclassifier predicates, they simply have no clear counterparts inspeech. From this perspective, speech appears to be ‘iconicallydeficient’ relative to sign.

But Goldin-Meadow and Brentari (2017) have argued that a typologicalcomparison between sign language and spoken language makes littlesense if it does not take gestures into account: sign with iconicityshould be compared to speech with gestures rather than to speechalone, since gestures are the main exponent of iconic enrichments inspoken language. This raises a question: From a semantic perspective,does speech with gesture have the same expressive effect and the samegrammatical integration as sign with iconicity?

5.2 Typology of iconic contributions in speech and in sign

This question has motivated a systematic study of iconic enrichmentsacross sign and speech, and has led to the discovery of fine-graineddifferences (Schlenker 2018b). The key issue pertains to the place ofdifferent iconic contributions in the typology of inferences, whichincludes at-issue contributions and non-at-issue ones, notablypresuppositions and supplements (the latter are the semanticcontributions of appositive relative clauses).

While detailed work is still limited, several iconic constructions insign language have been argued to make at-issue contributions(sometimes alongside non-at-issue ones). This is the case of iconicmodulations of verbs, as forGROW in(18), of repetition-based plurals and pluractionals, and of classifierpredicates.

By contrast, gestures that accompany spoken words have been argued inseveral studies (starting with the pioneering one by Ebert & Ebert2014 – see Other Internet Resources) to make primarilynon-at-issue contributions. Recent typologies (e.g., Schlenker 2018b;Barnes & Ebert 2023) distinguish between co-speech gestures, whichco-occur with the spoken words they modify (a slapping gestureco-occurs withpunish in(31a); post-speech gestures, which follow the words they modify (the gesturefollowspunish in (31b); and pro-speech gestures, which fully replace some words (the slappinggestures has the function of a verb in(31c).

- (31)

- a.

- Co-speech: His enemy, Asterix will

_punish.

_punish. - b.

- Post-speech: His enemy, Asterix will punish—

.

. - c.

- Pro-speech His enemy, Asterix will

.

.

When different tests are applied, such as embedding under negation,these three types display different semantic behaviors. Co-speechgestures have been argued to trigger conditionalized presuppositions,as in(32a). Post-speech gestures have been argued to display the behavior ofappositive relative clauses, and in particular to be deviant in somenegative environments, as illustrated in (32b)–(32b′); inaddition, post-speech gestures, just like appositive relative clauses,usually make non-at-issue contributions.

- (32)

- a.

- Co-speech: His enemy, Asterix won’t

_punish.

_punish.

\(\Rightarrow\) if Asterix were to punish his enemy, slapping would beinvolved - b.

- Post-speech: #His enemy, Asterix won’t punish—

.

. - b′.

- #His enemy, Asterix won’t punish, which will involveslapping him.

- c.

- Pro-speech His enemy, Asterix won’t

.

.

\(\Rightarrow\) Asterix won’t slap his enemy

(Picture credits: M. Bonnet)

Only pro-speech gestures, as in(32c), make at-issue contributions by default (possibly in addition to othercontributions). In this respect, they ‘match’ the behaviorof iconic modulations, iconic plurals and pluractionals, andclassifier predicates. But unlike these, pro-speech gestures are notwords and are correspondingly expressively limited. For instance,abstract psychological verbsUNDERSTAND (=(15a)) and especiallyREFLECT (=(15b)) can be modulated in rich iconic ways in LSF—e.g., if the handmovement ofREFLECT starts slow and ends fast, this conveysthat the reflection intensified (Schlenker 2018a). But there are noclear pro-speech gestures with the same abstract meanings, and thusone cannot hope to emulate with pro-speech gestures the contributionsofUNDERSTAND andREFLECT, including when they areenriched by iconic modulations.

In sum, while the reintegration of gestures into the study of speechopens new avenues of comparison between sign with iconicity and speechwith gestures, one shouldn’t jump to the conclusion that theseenriched objects display precisely the same semantic behavior.

5.3 Classifier predicates and pro-speech gestures

Unlike gestures in general and pro-speech gestures in particular,classifier predicates have a conventional form (only the position,orientation, and movement are iconically interpreted, accompanied inlimited cases by aspects of the handshape). But there are stillstriking similarities between pro-speech gestures and classifierpredicates.

First, on a semantic level, the iconic semantics sketched forclassifier predicates inSection 4.2 seems useful for pro-speech gestures as well, sometimes down to thedetails—for instance, it has been argued that the dependencybetween viewpoints and quantifiers illustrated in(30) has a counterpart with pro-speech gestures (Schlenker & Lambertonforthcoming).

Second, on a syntactic level, classifier predicates often display adifferent word order from other constructions, something that has beenfound across languages (Pavlič 2016). In ASL, the basic wordorder is SVO, but preverbal objects are usually preferred if the verbis a classifier predicate, for instance one that represents acrocodile moving and eating up a ball (as is standard in syntax, the‘basic’ or underlying word order may be modified onindependent grounds by further operations, for instance ones thatinvolve topics and focus; we are not talking about such modificationsof the word order here).

It has been proposed that the non-standard word order is directlyrelated to the iconic properties of classifier predicates. The idea isthat these create a visual animation of an action, and preferably taketheir argument in the order in which their denotations are visible(Schlenker, Bonnet et al. 2024; see also Napoli, Spence, andMüller 2017). One would typically see a ball and a crocodilebefore seeing the eating, hence the preference for preverbal objects(note that the subject is preverbal anyway in ASL). A key argument forthis idea is that when one considers a minimally different sentenceinvolving a crocodile spitting out a ball it had previously ingested,SVO order is regained, in accordance with the fact that an observerwould see the object after the action in this case.

Strikingly, these findings carry over to pro-speech gestures.Goldin-Meadow et al. (2008) famously noted that when speakers oflanguages with diverse word orders are asked to use pantomime todescribe an event with an agent and a patient, they tend to go withSOV order, including if this goes against the basic word order oftheir language (as is the case in English). Similarly, pre-verbalobjects are preferred in sequences of pro-speech gestures in French(despite the fact that the basic word order of the language is SVO);this is for instance the case for a sequence of pro-speech gesturesthat means that a crocodile ate up a ball. Remarkably, withspit-out-type gestural predicates, an SVO order is regained, just asis the case with ASL classifier predicates (Schlenker, Bonnet, et al.2024, following in part by Christensen, Fusaroli, & Tylén2016; Napoli, Mellon, et al. 2017; Schouwstra & de Swart 2014).This suggests that iconicity, an obvious commonality between the twoconstructions, might indeed be responsible for the non-standard wordorder.

6. Universal Properties of the Signed Modality

6.1 Sign language typology and sign language emergence

Properties discussed above include: (i) the use of loci to realizeanaphora, (ii) the overt marking of telicity and (possibly) contextshift, (iii) the presence of rich iconic modulations interacting withevent structure, plurals and pluractionals, and anaphora, (iv) theexistence of classifier predicates, which have both a conventional andan iconic dimension. Although the examples above involve a relativelysmall number of languages, it turns out that these properties exist inseveral and probably many sign languages. Historically unrelated signlanguages are thus routinely treated as a ‘languagefamily’ because they share numerous properties that are notshared by spoken languages (Sandler & Lillo-Martin 2006). Ofcourse, this still allows for considerable variation across signlanguages, for instance with respect to word order (e.g., ASL is SVO,LIS is SOV).

Cases of convergence also exist in language emergence. Homesigners aredeaf individuals who are not in contact with an established signlanguage and thus develop their own gesture systems to communicatewith their families. While homesigners do not invent a sign language,they sometimes discover on their own certain properties of mature signlanguages. Loci and repetition-based plurals are cases in point(Coppola & So 2006; Coppola et al. 2013). Strikingly, Coppola andcolleagues (2013) showed in a production experiment that a group ofhomesigners from Nicaragua used both punctuated and unpunctuatedrepetitions, with the kinds of semantic distinctions found in maturesign language. Coppola et al. further

examined a child homesigner and his hearing mother, and found that thechild’s number gestures displayed all of the properties found inthe adult homesigners’ gestures, but his mother’s gesturesdid not. (Coppola, Spaepen, & Goldin-Meadow 2013: abstract)

This provided clear evidence that this homesigner had invented thisstrategy of plural-marking.

In sum, there is striking typological convergence among historicallyunrelated sign languages, and homesigners can in some cases discovergrammatical devices found in mature sign languages.

6.2 Sign language grammar and gestural grammar

It is arguably possible to have non-signers discover on the flycertain non-trivial properties of sign languages (Strickland et al.2015; Schlenker 2020). One procedure involves hybrids of words andgestures. We saw a version of this inSection 5.3, when we discussed similarities between pro-speech gestures andclassifier predicates. The result was that along several dimensions,notably word order preferences and associated meanings, pro-speechgestures resemble ASL classifier predicates (they also differ fromthem in not having lexical forms).

More generally, hybrid sequences of words and gestures suggest thatnon-signers sometimes have access to a gestural grammar somewhatreminiscent of sign languages. (It goes without saying that there isno claim whatsoever that non-signers know the sophisticated grammarsof sign languages, any more than a naive monolingual English speakerknows the grammar of Mandarin or Hebrew.) In one experimental study(summarized in Schlenker 2020), gestures with a verbal meaning, suchas ‘send kisses’, targeted different positions,corresponding to the addressee or some third person, as illustratedbelow.

- (33)

- A gesture for ‘send kisses to’ oriented towards theaddressee or some third person position

a. send kisses to you

b. send kisses to him/her

Credits: J. Kuhn

The conditions in which these two forms can be used turn out to bereminiscent of the behavior of the agreement verbTELL inASL: in(5), the verb could target the addressee position to meanI tellyou, or some position to the side to meanI tellhim/her. The study showed that non-signers immediately perceiveda distinction between the second person object form and the thirdperson object form of the gestural verb, despite the fact thatEnglish, unlike ASL, has no object agreement markers. In other words,non-signers seemed to treat the directionality of the gestural verb asa kind of agreement marker. More fine-grained properties of the ASLobject agreement construction were tested with gestures, again withpositive results.

More broadly, it has been argued that aspects of gestural grammarresemble the grammar of ASL in designated cases involving loci,repetition-based plurals and pluractionals, Role Shift, and telicitymarking (e.g., Schlenker 2020 and references therein). These findingshave yet to be confirmed with experimental means, but if they arecorrect, the question is why.

6.3 Why convergence?

We have seen three cases of convergence in the visual modality:typological convergence among unrelated sign languages,homesigners’ ability to discover designated aspects of signlanguage grammar, and possibly the existence of a gestural grammarsomewhat reminiscent of sign language in designated cases. None ofthese cases should be exaggerated. While typologically they belong toa language family, sign languages are very diverse, varying on alllevels of linguistic structure. As for homesigners, the gesturalsystems they develop compensate for thelack of access to asign language; indeed, homesigners bear consequences of lack of accessto a native language (see for instance Morford &Hänel-Faulhaber 2011; Gagne & Coppola 2017). Finally,non-signers cannot guess anything about sign languages apart from afew designated properties.

Still, these cases of convergence should be explained. There are atleast three conceivable directions, which might have different areasof applicability. Chomsky famously argued that there exists an innateUniversal Grammar (UG) that underlies all human languages (see forinstance Chomsky 1965, Pinker 1994). One possibility is that UGdoesn’t just specify abstracts features and rules (as is usuallyassumed), but also certain form-to-meaning mappings in the visualmodality, for instance the fact that pronouns are realized by way ofpointing. A second possibility is that the iconic component of signlanguage—possibly in more abstract forms than is usuallyassumed—is responsible for some of the convergence. An examplewas discussed inSection 5.3 in relation to the word order differences between classifierpredicates and normal signs, and between gesture sequences and normalwords. A third possibility is that, for reasons that have yet to bedetermined, the visual modality sometimes makes it possible to realizein a more uniform fashion some deeper cognitive properties oflinguistic expressions.

7. Future Issues

On a practical level, future research will have to find the optimalbalance between fine-grained studies and robust methods of datacollection (e.g., what are the best methods to collect fine-graineddata from a small number of consultants? how can large-scaleexperiments be set up for sign language semantics?). A second issuepertains to the involvement of native signers and Deaf researchers,who should obviously play a central role in this entire research.